Introduction

Asylum policy debates in Western countries are characterised by agitated publics, mobilised political actors, partisan conflicts, and competing constructions of asylum seekers (Freeman Reference Freeman2006; Hamlin Reference Hamlin2012; Hatton Reference Hatton2012; Sirriyeh Reference Sirriyeh2018). In these public debates, policy narratives often link constructed policy problems with policy interventions (Fischer and Forester Reference Fischer and Forester1993; Boswell et al. Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011). The media, political parties, and civil society organisations are not the only ones conveying these narratives, governments do so as well (Boswell and Geddes Reference Boswell and Geddes2011, 157–161; Münch Reference Münch, Heinelt and Münch2018). In general, narratives often serve to interpret and simplify complex phenomena, such as forced migration and asylum governance, because they can stabilise the assumptions needed for policy interventions in uncertain and complex settings (Stone Reference Stone1989; Roe Reference Roe1994; Boswell et al. Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011).

One persistent policy narrative portrays asylum seekers as “bogus refugees” or “economic migrants” who try to abuse a country’s generosity and protection. In a nutshell, the abuse policy narrative constructs a policy problem (i.e. the abuse of benevolent asylum systems) and proposes a simple policy solution for it (i.e. tighter asylum policies). The abuse policy narrative is prevalent in policy and public discourses on asylum policies in European destination countries (Bloch Reference Bloch2000; Sales Reference Sales2002; Schuster Reference Schuster2004; Schuster and Solomos Reference Schuster and Solomos2004; Goodman and Speer Reference Goodman and Speer2007; Hänggli and Kriesi Reference Hänggli and Kriesi2010; Jennings Reference Jennings2010; Darling Reference Darling2014), boat arrivals in Australia (Zagor Reference Zagor2015), and migration discourses in the United States (McBeth and Lybecker Reference McBeth and Lybecker2018).

Given the prevalence of the abuse policy narrative, we analyse its use and effect in asylum policy debates. We rely on and combine multiple policy studies frameworks, namely the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017), social construction of target groups (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993), and policy mass feedback effects (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007), to better understand the abuse policy narrative and the role of narratives in the politicised field of asylum policy. In the empirical analysis, we focus on how political elite actors convey the asylum abuse policy narrative vis-à-vis other narratives and how it is associated with citizens’ opinion formation. By doing so, we are able to juxtapose meso- and micro-level analyses of policy narratives. This combination is an underdeveloped aspect of narrative policy analysis (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017, 197; Schlaufer et al. Reference Schlaufer, Kuenzler, Jones and Shanahan2022). This article therefore contributes to current developments in the NPF that seek to expand the understanding of the connections between the different levels of analysis (Crow Reference Crow2012; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017, 196). Because the abuse policy narrative resembles narratives in welfare state debates, this article may also be relevant for studying the constructions revolving around deservingness in welfare politics or the phenomenon of “welfare chauvinism” (Crepaz and Damron Reference Crepaz and Damron2009; Petersen et al. Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011; Boräng Reference Boräng2015; Blum and Kuhlmann Reference Blum and Kuhlmann2019).

We focus on Swiss direct democratic campaigns during which political elite actors use policy narratives and policy frames to mobilise citizens (e.g. Stucki Reference Stucki2017; Schlaufer Reference Schlaufer2018; Stucki and Sager Reference Stucki and Sager2018). The abuse policy narrative is well established in the Swiss asylum discourse and is connected to the rise of the radical right Swiss People’s Party in the 1980s (Inderbitzin Reference Inderbitzin2002; Leyvraz et al. Reference Leyvraz, Rey, Rosset and Stünzi2020). Given the prevalence of the abuse policy narrative, we go beyond simply detecting the presence of this policy narrative in the Swiss discourse to study its conveyance by political elite actors and how it is associated with citizens’ opinion formation. We hypothesise that at both the meso- and the micro-levels the policy orientation of the reform at stake, and the political ideology of actors are crucial to the use and the effect of the abuse policy narrative. In terms of policy orientation, we expect the abuse policy narrative to be more important for both political elite actors and citizens to the extent that a referendum contains tightening policies (i.e. measures that enhance the restrictiveness of asylum policies) as opposed to streamlining reforms (i.e. measures that enhance efficiency and speed up asylum procedures and systems). In terms of political ideology, we expect that both elite actors and citizens are more likely to rely on the abuse policy narrative if they are farther to the right.

To test these hypotheses, we select three paradigmatic cases: the 2006, 2013, and 2016 Swiss referendums on asylum legislation. The 2006 referendum proposed a decisive tightening, whereas the 2016 referendum was a paradigmatic case of streamlining. The 2013 referendum is a more balanced case containing both tightening and streamlining policies. On the meso-level, the empirical analysis includes 108 face-to-face survey interviews with campaign managers of participating political organisations prior to these three referendums. On the micro-level, we use VOX post-vote surveys to assess the effect of the abuse policy narrative on citizens’ opinion formation.

We find that the role of the abuse policy narrative varies greatly across referendums. More specifically, political organisations and citizens were most likely to rely on the abuse policy narrative in the tightening reform of 2006, followed by the balanced reform of 2013, and the streamlining reform of 2016. As for political organisations, the farther to the right an actor was, the more likely that actor was to employ the abuse policy narrative in referendum campaigns on Swiss asylum policy. A similar pattern emerges from the analysis of citizens’ opinion formation. However, a finer-grained analysis reveals that, relative to citizens on the left, not only those on the right but also those in the centre were more likely to base their decision on the abuse policy narrative.

Abuse as a policy narrative

Narratives are crucial for politicians, parties, strategists, and media reporters given the importance of how a story is rendered for policymaking (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017). Narratives can legitimate a policy through their construction of policy problems and proposed solutions, and they link policy problems and solutions by means of a plot or a story (Schlaufer Reference Schlaufer2018; Stauffer and Kuenzler Reference Stauffer and Kuenzler2021).

Policy narratives and social constructions

The Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) has emerged as the key framework by which to study narratives in policy processes (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones and McBeth2011; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017; Stauffer and Kuenzler Reference Stauffer and Kuenzler2021; Schlaufer et al. Reference Schlaufer, Kuenzler, Jones and Shanahan2022). The NPF outlines a general structure of policy narratives that contains four core elements: setting, characters, plot, and moral. The setting accounts for the embeddedness of policy narratives in the specific institutional, geographical, legal, and economic context. Policy narratives contain characters: “As with any good story, there may be victims who are harmed, villains who do the harm, and heroes who provide or promise to provide relieve from the harm and presume to solve the problem” (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017, 176). The plot establishes the relationships between the characters and situates the characters within the policy setting. It serves as the arc of the action within the narrative. The policy solution that “solves” the problem is the moral of the story (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017, 175–177).

Policy narratives thus link policy problems with policy designs and they establish which actors are allegedly responsible for the problem. They thereby rely on the social construction of target groups (Stucki Reference Stucki2017). These social constructions are stereotypes about particular groups of people created by politics, culture, or the media (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993); they can depict citizens’ perceptions and can pervade all aspects of political reality (Pierce et al. Reference Pierce, Siddiki, Jones, Schumacher, Pattison and Peterson2014). Policymaking and political behaviour can be directed by these stereotypes “without personally endorsing such stereotypes, without feelings of prejudice, and without awareness that such stereotypes could affect one’s judgement and behaviour” (Vescio and Weaver Reference Vescio and Weaver2013, 1; see also Thomann and Rapp Reference Thomann and Rapp2018). The social constructions of target groups have important consequences for the design of policies that can be geared benevolent or resentful to these diverse groups (Schneider and Sidney Reference Schneider and Sidney2009).

Political actors often disagree about these constructions (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Schneider and Sidney Reference Schneider and Sidney2009). In the terminology of Schneider and Ingram (Reference Schneider and Ingram1993), asylum seekers, as a target group, can be socially constructed as victims or as dependents that are in need of protection. On the other hand, they can also be constructed as villains or deviants abusing generous asylum systems. The social construction of policy target groups depends on how people perceive the deservingness of asylum seekers (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Thomann and Rapp Reference Thomann and Rapp2018; Blum and Kuhlmann Reference Blum and Kuhlmann2019).

Narratives operate and can be studied on three interacting levels of analysis: micro (individual), meso (group), and macro (institutions and culture) (McBeth et al. Reference McBeth, Jones, Shanahan, Weible and Sabatier2014; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017; Stauffer and Kuenzler Reference Stauffer and Kuenzler2021). On the macro-level, researchers may look at how policy narratives are embedded in public debates, culture, and institutions. On the meso-level, they may examine how groups and political elite actors convey and make use of policy narratives. On the micro-level, they can analyse how individuals inform themselves and are informed by policy narratives. Although there exist ample NPF studies at the meso- and micro-levels, relatively few studies connect the NPF’s different levels of analysis (Crow Reference Crow2012; McBeth et al. Reference McBeth, Jones, Shanahan, Weible and Sabatier2014; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017; Schlaufer et al. Reference Schlaufer, Kuenzler, Jones and Shanahan2022).

The abuse policy narrative

The abuse policy narrative portrays asylum seekers as “economic migrants” and “bogus refugees” who try to abuse the host country’s generosity and protection (Leyvraz et al. Reference Leyvraz, Rey, Rosset and Stünzi2020). It constructs asylum seekers as villains tapping into welfare resources. It furthermore suggests that the complex problems of asylum governance in countries of the Global North are caused primarily by the actions of asylum seekers. This allegation provides the foundation of the abuse policy narrative with the opportunity to constructing a policy problem that is amenable to policy interventions.

These social constructions of asylum seekers as abusers are prevalent in public debates in Europe. In the UK, for example, asylum seekers are portrayed as either “bogus” or “genuine,” with the former category seen as undeserving of sympathy and support (Sales Reference Sales2002; Goodman and Speer Reference Goodman and Speer2007). Similar competing constructions appeared in debates during and in the aftermath of the so-called European “refugee crisis” of 2015Footnote 1 (Crawley and Skleparis Reference Crawley and Skleparis2018). Sager and Thomann (Reference Sager and Thomann2017) point out that the different social constructions of asylum seekers can shape subnational policy designs in Switzerland, mainly because these constructions influence how political actors frame the policy problem.

The proposed policy solution in the abuse policy narrative is tighter asylum policies. The tightening can aim to make access to asylum systems more difficult or to create stricter or tougher conditions for those already in the asylum system (see Bernhard and Kaufmann Reference Bernhard and Kaufmann2018). On one hand, states can try to impede asylum seekers’ entry into their territory, thereby preventing them from submitting an asylum application and entering the refugee status determination procedure. Alternatively, states can implement stricter rules for people already in the asylum system. Tightening of policies can target the refugee status determination procedure, welfare benefits, or the living conditions of asylum seekers.

The abuse policy narrative argues that such tightening reduces a country’s attractiveness as an asylum destination, especially to people who allegedly choose their destination country because of its generosity. Thus, the narrative claims that tighter policies solve the constructed asylum problem by making it harder for asylum seekers to abuse the system. We should note that the effectiveness of tighter asylum policies is highly disputed (e.g. Thielemann Reference Thielemann2012). In fact, this claim is in itself an often-used narrative (Boswell et al. Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011, 5). Furthermore, tightening access to asylum systems is highly controversial from legal and moral points of view since all asylum seekers are affected by it, regardless of whether they need protection.

The politicisation of asylum policy

Asylum policy tends to be highly contested and politicised in receiving countries (e.g. Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frei2008; Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015; Bernhard and Kaufmann Reference Bernhard and Kaufmann2018; Bazurli and Kaufmann Reference Bazurli and Kaufmann2022). Soss and Schram (2017) offer a typology of policy fields’ potential to create mass feedback effects that can help us understand this politicisation of asylum policy. The authors postulate that the dimensions of proximity and visibility are crucial in determining whether a policy field is likely to create mass feedback effects. Proximity describes the extent to which a policy field affects voters’ lives in immediate and tangible ways. This framework assumes that the public can evaluate proximate policies without having to rely heavily on media and elite interpretations, whereas policy fields that are more distant from the electorate allow political elites to frame or narrate a policy according to their own specific needs (Hinterleitner Reference Hinterleitner2018). Visibility describes the salience of the policy to the mass public. Highly visible policies are likely to produce stronger feedback effects, and the debates on them are more likely to occur in public and to be depicted according to policy narratives.

In this typology, asylum policy is a distant but visible policy field (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007). While asylum policy mainly affects the political and societal “out-group” of asylum seekers and thus is distant from voters, it is also highly visible in public debates and the media. Policies with these characteristics “exist for publics as rumours about what the state is doing somewhere else. (…) Mass publics are highly dependent on mediated constructions of such policies and, accordingly, elite and media frames are more likely to structure and condition mass feedback effects” (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007, 122). For this reason, asylum policy is prone to being narrated or framed by political elites according to their own specific needs, and its visibility makes it prone to generate mass effects, all of which makes asylum policy highly politicised.

Policy narratives in Swiss direct democracy

Policy narratives are frequently conveyed in Swiss direct democratic campaigns (Stucki Reference Stucki2017; Schlaufer Reference Schlaufer2018; Kuenzler Reference Kuenzler2021; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2022). They are important because they can activate and reinforce citizens’ previously held opinions and mobilise them to vote (Kear and Wells Reference Kear, Wells, Jones, Shanahan and McBeth2014; Schlaufer Reference Schlaufer2018). Since citizens have the final say on policy proposals in Switzerland, political elites have a strong incentive to rely publicly on policy narratives during the public debate that precedes a vote. Given the importance of policy narratives in Swiss politics, the NFP and especially its structure (setting, characters, plot, and moral) have been extensively applied to detect and study policy narratives in such areas as education (Schlaufer Reference Schlaufer2018), health (Stucki Reference Stucki2017), or child and adult protection (Kuenzler Reference Kuenzler2021; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2022).

In Swiss direct democracy, asylum policy referendums are often politicised by political elite actors, who employ policy narratives to influence citizens’ opinion formation. The abuse policy narrative has been established in discourses around asylum referendums since the 1980s (Inderbitzin Reference Inderbitzin2002; Leyvraz et al. Reference Leyvraz, Rey, Rosset and Stünzi2020). Although asylum seekers usually account for only about 10 to 15 per cent of immigrants in Switzerland, this category of immigrants has preoccupied politicians and citizens more than any other subset of the country’s foreign population in recent years (Bernhard Reference Bernhard2012; Piguet Reference Piguet2017). Over the last three decades, intensive public debates on asylum policies have occurred repeatedly in the context of Swiss direct democratic votes (Bernhard Reference Bernhard2012, 41–45). Since the introduction of the federal asylum law in 1981, it has been subject to no less than eleven major reforms, including a complete revision in 1999. Many of the reforms of the federal asylum law were challenged by civil society actors (such as human rights groups, refugee aid organisations, charities, and churches) and also sometimes by right-wing dissidents. As a result, there have been six referendums on revisions and modifications of the federal asylum law. Voters clearly rejected these referendums at the polls in all six instances,Footnote 2 thereby favouring tighter asylum policies and strengthening the position of the federal authorities and the right. In addition, the radical right Swiss People’s Party launched two popular initiatives regarding asylum policies.Footnote 3

A closer look at Swiss asylum reforms shows that Swiss decisionmakers have relied on two asylum policy trends that can also be observed in other Western destination countries (Parini and Gianni Reference Parini, Gianni and Mahnig2005, 209; Bernhard and Kaufmann Reference Bernhard and Kaufmann2018). First, Swiss federal authorities have made asylum legislation more restrictive by engaging in a continuous tightening process. Second, they have frequently enacted streamlining policies, which seek to make asylum procedures more efficient.

Hypotheses

In the empirical part of this article, we focus on the meso- and micro-levels of the NPF. More specifically, we examine the conveyance of the abuse policy narrative by political elite actors and its association with citizens’ opinion formation. We compare the abuse policy narrative to other prevalent narratives and political messages in referendum campaigns. Given the prevalence and entrenchment of the abuse policy narrative in Swiss asylum policy debates (Inderbitzin Reference Inderbitzin2002; Leyvraz et al. Reference Leyvraz, Rey, Rosset and Stünzi2020) and the extensive detection of policy narratives in Swiss public debates (e.g. Schlaufer Reference Schlaufer2018; Kuenzler Reference Kuenzler2021; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2022), we refrain from detecting and describing the asylum policy narrative according to the structure proposed by the NPF. Rather, we go beyond the detection and description of this policy narrative to focus on explaining (1) the conveyance of the abuse policy narrative and (2) its association with citizens’ opinion formation. Our analysis is guided by four hypotheses, two regarding the narrative’s conveyance by political elite actors (meso-level) and two concerning the effect on citizens’ opinion formation (micro-level). For each level of analysis, we formulate one hypothesis on the policy orientation of policy reforms and one on political ideology.

With regard to policy orientation on the meso-level, we expect political elite actors to be more likely to employ the asylum abuse policy narrative in the context of tightening asylum reforms than in the case of streamlining asylum reforms. This hypothesis fits well with core assumptions of the NPF that anticipate a strong role of the specific context (labelled as the setting) in the policy discourse and its employed policy narratives (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017). With regard to political ideology on the meso-level, we expect that the farther to the right political elites are the more likely they are to rely on the asylum abuse policy narrative. Conflicts over asylum policies in Western Europe are largely structured along the left–right axis (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frei2008; Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2021). Mobilisations by the new left and the Greens, as well as by the radical right, have increasingly politicised this conflict dimension (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010). Right-leaning political elite actors have continuously mobilised their voters to support tightening of asylum policies, while the left and its civil society allies have kept trying to maintain the status quo or to strengthen the rights of asylum seekers. Actors from moderate parties generally take an intermediate stance (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frei2008; Akkerman Reference Akkerman2015). This conflict structure is also observable in Switzerland, where the radical right blames the federal authorities for not doing enough to prevent abuses of the asylum system, while political elite actors and NGOs on the left accuse the right of violating humanitarian principles (Steiner Reference Steiner2000; Inderbitzin Reference Inderbitzin2002).

H1a: The more an asylum reform includes tightening policies, the more political elite actors rely on the abuse policy narrative.

H1b: The more to the right the political ideology of political elite actors is, the more likely they are to rely on the abuse policy narrative.

The same logic applies to the micro-level hypotheses. We expect that citizens’ opinion formation is more likely to rely on the abuse policy narrative in the context of tightening asylum reforms than in the case of streamlining asylum reforms. Given the above-described conflict structure around asylum issues, we expect that the farther to the right citizens’ position themselves, the more they will rely on the asylum abuse policy narrative in their opinion formation.

H2a: The more an asylum reform includes tightening policies, the more citizens’ opinion formation is based on the abuse policy narrative.

H2b: The more to the right the political ideology of citizens is, the more their opinion formation is based on the abuse policy narrative.

Research design

The empirical analysis investigates the use and effect of the abuse policy narrative vis-à-vis other narratives and messages in the context of the three most recent asylum referendum campaigns at the Swiss federal level (2006, 2013, and 2016). As we explain in the next section, the three referendums differed in terms of their policy orientation. This case selection allows us to compare the impact of the policy orientation on the use and effect of the abuse policy narrative.

The cases

The 2006 referendum represented a decisive tightening of the Swiss asylum legislation, whereas the 2016 referendum was a paradigmatic case of streamlining. The 2013 referendum was a more balanced case containing both tightening and streamlining policies. We will briefly summarise the main contents of these three referendums.

The 2006 revision contained some highly controversial tightening provisions (Bernhard Reference Bernhard2012, 69–72). These included the prohibition of social assistance for asylum seekers whose requests had been rejected, more restrictive rules for asylum seekers without identification, more drastic coercive measures (such as longer maximum detention pending deportation and an enforcement detention of up to two years for anyone who received a deportation decision and was reluctant to leave the country), and more restrictive asylum procedures at airports. The bill also stipulated that requests from asylum seekers who were already in so-called secure third states would not be processed by Swiss authorities.

The modifications of the asylum law adopted by Swiss citizens in 2013 included four tightening and four streamlining provisions (Bernhard and Kaufmann Reference Bernhard and Kaufmann2018, 2514–2515). The tightening provisions included a ban on the possibility of applying for asylum at Swiss embassies, the denial of refugee status for deserters, the creation of special centres to house so-called “troublemakers” (i.e. asylum seekers who refuse to cooperate with the authorities), and the reduction of appeal periods for rejected asylum requests. The streamlining policies included the testing of the proposed structural reforms in a reception centre, giving greater power to the federal authorities over the cantons (Switzerland’s 26 member states) to cope with the challenge posed by volatile numbers of asylum seekers, and two measures providing the cantons with higher federal subsidies (specifically, flat-rate subsidies to cover additional security costs and financial contributions to employment programmes).

The 2016 referendum fully adhered to a streamlining reform that the Swiss authorities modelled on asylum reforms in the Netherlands (Bernhard and Kaufmann Reference Bernhard, Kaufmann, Leyvraz, Rey, Rosset and Stünzi2020). The goal of the asylum provision was to enhance procedures so that refugee status determination would take no more than a year, as opposed to the average time of two years prior to reform. To speed up refugee determination procedures, the provision proposed creating new reception centres to be run by the Confederation that would process asylum seekers with a high likelihood of receiving a negative decision. It also proposed assigning the responsibility for asylum seekers to cantons only in the case of complex applications that were likely to be successful and would require further evaluation of asylum claims. Additionally, it proposed providing asylum seekers with the right to benefit from free legal advice.

Data and measurements

Our analysis of how political elite actors convey the abuse policy narrative examines an original dataset that we compiled by conducting 108 face-to-face survey interviews with the campaign managers of organisations that actively participated in the referendum campaigns of 2006, 2013, and 2016 (see Table A1 in the Appendix). In the context of Swiss referendum campaigns, the main political elite actors are the political organisations that take part in the campaigns. We selected these political elite actors on the basis of various sources, such as the parliamentary debates, participation in the collection of signatures, voting recommendations, media sources, or insider information from previous respondents. Given the comprehensiveness of this pragmatic procedure, we feel confident that we included the most important organisations for all three referendum campaigns. We selected 46 political elite actors for the 2006 referendum and 31 actors for each of the two other cases. To avoid biases due to ex post facto rationalisations in the response behaviour, we performed ex-ante surveys with each campaign manager.

For each referendum case, the surveys took place after the successful collection of signatures over a time span of roughly six weeks, beginning with the official announcement of the voting date and ending before the start of the intensive campaign phase, which typically takes place during the last four weeks before the vote. One author of this article led the data collection in all three surveys. Two people carried out the scheduling and conducting of the surveys for the first two referendums, and four persons shared these tasks for the 2016 referendum. Most survey respondents needed between 40 and 60 minutes to answer a structured questionnaire that contained about 100 closed- or open-ended questions.Footnote 4 Since we rely on a selection of closed-ended answers, we have analysed these quantitative survey data using multivariate regression methods.

We measure our dependent variable, the salience of the abuse policy narrative for political elite actors, by relying on questions about key narratives or messages that we believed could be important in the three referendums under scrutiny. In the framework of ex-ante surveys, we presented the campaign managers with a list of 12 key narratives and messages in 2006 and 2013 and 13 key narratives and messages in 2016. Although these lists of key narratives and messages vary slightly to suit the context of each proposed reform (see Table A2 in the Appendix for the full lists), one of the key narratives or messages in each case refers to the abuse policy narrative. We used the following wording for this item: “Abuses in the asylum system must be combated.”Footnote 5 We then asked the various campaign managers to classify these narratives and messages according to their importance during the campaign communication.Footnote 6 First, we invited the respondents to choose the three most important narratives and messages. Next, we asked them to select the most important of these three. Finally, we asked campaign managers to choose the three least important ones from the remaining narratives and messages. Based on the answers obtained, we constructed a scale ranging from 0 to 3 using the following scheme:

-

3 for the single most important narrative and message,

-

2 for the following two important narratives and messages,

-

1 for the six or seven moderately important narratives and messages, and

-

0 for the three least important narrative and messages.

For each reform, we selected the scores that campaign managers assigned to the asylum policy narrative items; the other items were present purely as alternatives that enabled us to establish the scale described above. This approach to measuring the conveyance of the abuse policy narrative allows us to capture the degree of salience the various political organisations intended to devote to that narrative.

Our first independent variable is the policy orientation of the three referendums (see subsection “The Cases”). To test hypothesis H1a, we set the 2013 balanced reform as the reference group. For hypothesis H2a, we use the self-reported left–right placement of the selected organisations as the independent variable. As is typical in public opinion research, this scale ranges from 0 (completely left) to 10 (completely right).

We control for the influence of three variables: camp affiliation, actor type, and language region. With regard to camp affiliation, we draw a distinction between reformers (the “yes side”), on one hand, and political actors in favour of the status quo or against the reform (the “no side”), on the other hand. Hence, organisations in the former category were coded as 1, while the latter ones were coded as 0. Since the policy direction of all three reforms is similar (i.e. to make the asylum system more efficient and/or to tighten the rights of asylum seekers), all three campaigns can be compared using our label of reformers. Regarding actor types, we distinguish between political parties, interest groups, committees, and state actors (see Table A1 in the Appendix). We define the modal category “interest groups” as the reference category. We also control for the language region, because political elite actors in French-language regions of Switzerland tend to hold a more liberal position on immigration-related issues than those in the rest of the country (Bernhard Reference Bernhard2012, 47). We construct a dichotomous variable by coding the organisations based in the French-speaking part of Switzerland (n = 16) as 1 and the remaining ones as 0.

We now turn to the time frames and measurements used for the micro-analysis. To assess the effects of the abuse policy narrative on citizens’ opinion formation, we used the VOX post-vote surveysFootnote 7 for the selected referendums of September 2006 (Milic and Scheuss Reference Milic and Scheuss2006), June 2013 (Nai and Sciarini Reference Nai and Sciarini2013), and June 2016 (Colombo et al. Reference Colombo, De Rocchi, Kurer and Widmer2016). VOX surveys were carried out during the two or three weeks following all Swiss direct democratic ballots from 1977 to June 2016 by the private pollster GFS, in conjunction with the Universities of Bern, Geneva, and Zurich, on behalf of the Swiss Federal Chancellery. These standardised surveys provide researchers with a unique database for the analysis of citizens’ voting behaviour in Switzerland’s direct democracy. They ask a representative sample of Swiss eligible voters various questions regarding the vote that just occurred.Footnote 8

We make use of an open-ended question in which citizens could state the main reason for their voting decision. After an initial screening of the stated main reason in the three VOX surveys, we could detect three inductively constructed categories that we coded as belonging to the abuse policy narrative: (1) “abuse” (general); (2) “there is too much abuse,” “we have to fight abuse,” “stop abuse,” “curb the abuse”; (3) “stricter handling of ‘bogus’ asylum seekers,” “‘real’ asylum seekers are not put in a worse position,” and “more control.”

Regarding the independent variable of political ideology, we use a question that asks respondents to place themselves on a scale ranging from “completely left” (0) to “completely right” (10). This measurement thus matches the political ideology measurement of the political elite actors in the meso-level analysis.

We introduce five control variables in the multivariate analysis. First, we take into account a measure of camp affiliation in the same way as in the meso-level analysis. Based on individual voting decisions, we draw a distinction between reformers and adherents to the status quo. Whereas the former accepted the proposition under consideration, the latter came out against it. In addition, we control for the three standard socioeconomic factors of gender (women = 1, men = 0), age (in years), and education. Regarding education, we followed the approach taken by the VOX post-vote surveys, which distinguish between high (3), medium (2), and low (1) levels of formal education. Finally, we take into account which of Switzerland’s main language regions (German-speaking, French-speaking, and Italian-speaking) each respondent belongs to. In this regard, we rely on dichotomous variables by setting the modal category “German-speaking part” as the reference category.

Results

We test our hypotheses on the basis of multivariate regression analyses. We first examine the meso-level by looking at the use of the abuse policy narrative by political elite actors. Subsequently, we devote our attention to the micro-level, examining the association of the abuse policy narrative with citizens’ opinion formation by analysing post-vote surveys.

Meso-level: the use of the narrative by political elite actors

On the meso-level, the salience of the abuse policy narrative, our dependent variable, varied greatly across the three different referendums. The average salience measure of the abuse policy narrative among surveyed political organisations was the highest for the 2006 campaign (at 1.35). In 2013, which we consider a balanced case in terms of policy orientation, the average salience measure was 1.16. The 2016 streamlining reform obtained the lowest salience measure (0.81). These mean values are therefore in line with hypothesis H1a.

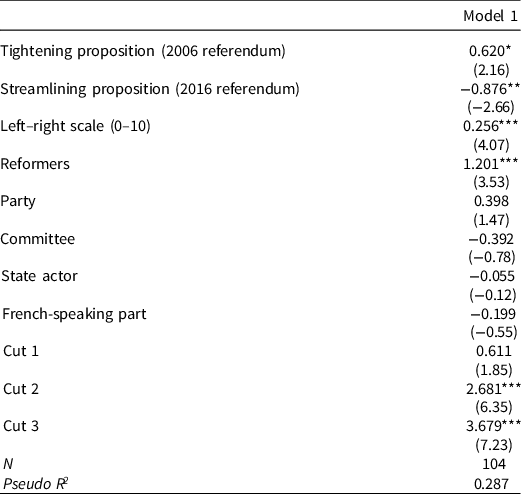

We now test whether a multivariate regression analysis confirms these observed patterns. Table 1 shows the results of the ordered probit model. The first two coefficients are in accordance with hypothesis H1a. First, the political organisations relied more strongly on the abuse policy narrative during the campaign preceding the 2006 tightening reform than in the campaign preceding the 2013 balanced reform. Second, reliance on the abuse policy narrative proved to be less important in the 2016 referendum on the streamlining proposition than in the balanced case of 2013. Taken together, the results indicate that elite actors are more likely to place emphasis on the abuse policy narrative if the proposed reform includes tightening policies more heavily. Regarding hypothesis H1b, the salience of the abuse policy narrative increases for political actors positioned farther to the right. Therefore, our multivariate analysis supports both meso-level hypotheses.Footnote 9

Table 1. Ordered probit model explaining the reliance on the abuse policy narrative by political organisations (meso-level)

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001; z-values in brackets.

Reference categories: Balanced proposition (2013 referendum) and interest groups (for actor types). See Table A4 in the appendix for descriptive statistics.

As for the control variables, we find that the reformers are more likely to rely on the abuse policy narrative than the opponents of a given referendum. This finding makes sense, since these asylum reforms tend to be tightening in nature, and thus, the reformers are more likely to rely on a narrative that portrays asylum seekers negatively. In contrast, we do not report any significant differences across actor types. The same holds true with respect to language regions. Organisations from the French-speaking part of Switzerland do not place less emphasis on the abuse policy narrative than other organisations.

Micro-level: the effect on citizens’ opinion formation

The data from the 2006 VOX survey show that the abuse policy narrative was crucial in that referendum, as more than one-fifth (21.7%) of citizens reported that it was decisive in their opinion formation. This finding is especially striking when compared with the other two referendums, in which the asylum abuse policy narrative was of only marginal importance for citizen’s opinion formation. Relative to the 2006 tightening reform, the abuse policy narrative was mentioned about four times less frequently in 2013 (5.4%) and 30 times less frequently in 2016 (0.7%). These figures therefore support hypothesis H2a.

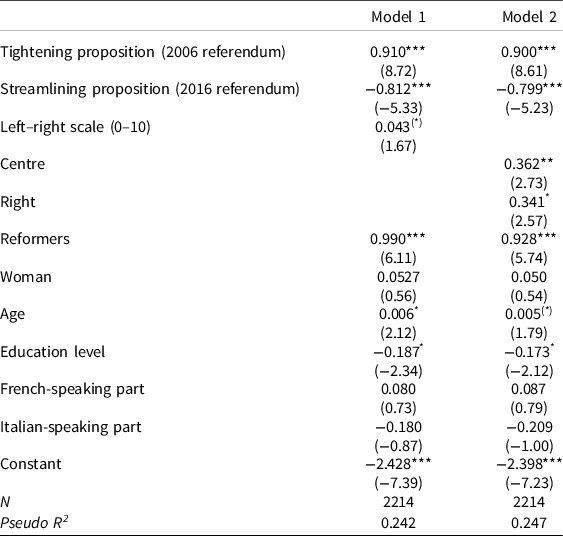

We now test whether a multivariate regression analysis confirms these patterns (see Table 2). As the first model shows, compared to the balanced proposition (2013 referendum), the abuse policy narrative was more important for citizens’ opinion formation regarding the tightening proposition (2006 referendum) and less important with regard to the streamlining proposition (2016 referendum). These findings are in line with hypothesis H2a.

Table 2. Probit model explaining the reliance on the abuse policy narrative by citizens (micro-level)

(*) p < 0.10;

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001; z-values in brackets.

Reference categories: Balanced proposition (2013 referendum), inhabitants of German-speaking part (for language regions), and leftist voters (for ideological camps in Model 2).

See Table A5 in the appendix for descriptive statistics.

Regarding hypothesis H2b, the following pattern emerges from the first model: the farther to the right citizens’ position themselves on the left–right scale, the greater their reliance on the abuse policy narrative. Since this coefficient proves to be significant only at the 10% significance level, however, hypothesis H2b is only weakly confirmed from a statistical point of view.Footnote 10

While we find that the abuse policy narrative tends to be more important the farther to the right citizens place themselves on the political ideological spectrum, a deeper analysis of political ideology reveals a divide between citizens on the left and all others. This is visible in the second model of Table 2, which replaces the left–right scale with a distinction between left-leaning, centrist, and right-leaning voters. The significant negative coefficient for the left-leaning voters indicates that these voters were less likely to base their voting decision on abuses than centrist voters, who serve as the reference category. In contrast, the coefficient for the right-leaning voters proves to be insignificant. This means that the abuse policy narrative resonates equally well among centrist voters and those on the right. We believe this is an important result because, although the meso-level analysis shows that political elite actors from the right primarily convey this narrative, it resonates well beyond voters on the right and is also important to the opinion formation of centrist voters. This finding is particularly crucial since centrist voters are usually decisive in the outcomes of direct democratic referendums.

Finally, three control variables exhibit a significant statistical association. First, the reformers (i.e. those citizens who voted yes) are more likely to base their decisions on abuse-related considerations than those who opposed the selected propositions. Second, age turns out to be of importance. The older a citizen is, the more likely she or he is to rely on the abuse policy narrative. Third, the same relationship holds true for respondents with lower levels of formal education. By contrast, the importance of the abuse policy narrative in terms of opinion formation is a function of neither gender nor language region affiliation.

Conclusion

Given the persistent accusation in public debates in Western countries that asylum seekers abuse the asylum systems designed to receive them, we have examined how political elite actors convey the abuse policy narrative and its association with citizens’ opinion formation in three direct democratic campaigns on asylum policy in Switzerland. We rely on analyses that connect two different levels (the meso- and micro-levels) on which narratives can operate, and we believe this combination constitutes an important contribution to narrative policy analysis (see also Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2017; Schlaufer et al. Reference Schlaufer, Kuenzler, Jones and Shanahan2022). Our empirical study is based on 108 face-to-face survey interviews conducted with campaign managers of political organisations prior to these asylum referendums, to examine their use of the asylum abuse policy narrative at the meso-level. We then test the effect of this narrative by using post-vote surveys of citizens to examine the effects of this narrative on citizens’ opinion formation (micro-level).

We find at the meso-level that that political elite actors more strongly rely on the abuse policy narrative (1) the farther to the right their political ideology is and (2) the more a referendum proposal contains tightening policies as opposed to streamlining policies. Although the second finding also applies to our micro-level analysis of citizens’ opinion formation, the results regarding the effect of political ideology prove to be less straightforward. Compared to voters who lean ideologically to the left, not only those on the right but also those in the centre are more likely to base their decision on the abuse policy narrative. Thus, the findings in this article corroborate conventional wisdom that actors from the right rely on the abuse policy narrative. However, the article adds nuance by showing that it resonates with citizens from both the right and the centre of the political spectrum.

The finding that this policy narrative falls on fertile ground among centrist voters can be considered important from the point of view of median voter theory. According to the classical models in the tradition of Black (Reference Black1948), this group is indeed assumed to be of pivotal importance in direct democratic votes, since such contests are characterised by majority rule with two options. The fact that the abuse policy narrative in asylum policy has the potential to expand its reach beyond those who identify with the right and to also attract the median voter is thus crucial for the outcomes of ballot measures on asylum matters and makes the abuse policy narrative very powerful.

This article offers an analysis and discussion of the popular accusation, prevalent in many asylum destination countries, that asylum seekers try to abuse a country’s generosity and protection (see also Schuster Reference Schuster2004; Hänggli and Kriesi Reference Hänggli and Kriesi2010; Zagor Reference Zagor2015). We expect that the abuse policy narrative will be powerful in policy debates other than asylum policies and beyond referendum campaigns in Switzerland. The abuse policy narrative seems to resemble narratives in welfare state discussions. Thus, these findings may also be relevant to how political elite actors convey welfare state abuse accusations, the construction of deservingness in welfare politics, or the proliferation of “welfare chauvinism” (Crepaz and Damron Reference Crepaz and Damron2009; Petersen et al. Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011; Boräng Reference Boräng2015; Blum and Kuhlmann Reference Blum and Kuhlmann2019). We would not expect political elite actors to randomly employ the abuse policy narrative in other contexts. Instead, we believe that actors on the political right strategically activate and convey this narrative. However, because these debates about Swiss asylum policies took place in the context of direct democratic campaigns, political elite actors may have used the abuse policy narrative more intensively and frequently than in other policy debate contexts.

We also show that the claim that a large proportion of asylum seekers are “economic migrants” or “bogus refugees” trying to abuse the country’s generosity and protection is a narrative strategically used by actors from the political right and that a large proportion of citizens find this narrative convincing. The persuasiveness of this narrative may be explained by its activation of a simple but, in reality, unobservable dichotomy between refugees who are “worthy” of protection and “bogus” (economic) migrants (Darling Reference Darling2014; Crawley and Skleparis Reference Crawley and Skleparis2018). It may also be persuasive because it constructs a policy problem that coincides with a preferred policy solution. It therefore flips the (assumed) order of the policy process, which usually defines a problem and then designs a policy to solve it. Boswell and Geddes (Reference Boswell and Geddes2011, 157–161) also find this type of reversed policymaking processes in EU asylum policy debates. Thus, the abuse policy narrative is not only an exemplary case of a narrative that links the construction of a policy problem with a policy intervention (Fischer and Forester Reference Fischer and Forester1993; Boswell et al. Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011) but also a case of a politically constructed policy design (Schneider and Sidney Reference Schneider and Sidney2009). Against this background, the present article sheds light on the strategic use of narratives by actors from the political right and their widespread influence due to their ability to persuade citizens located towards the middle of the political spectrum.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X22000356

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AF7HMD (see also Kaufmann and Bernhard Reference Kaufmann and Bernhard2022). Replication materials for the micro-analyses are not publicly available due to legal reasons but the raw data can be obtained at SWISSUbase (https://www.swissubase.ch/en/catalogue/studies/225/17151/overview).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Petra Mäder, Julia Meier, Tenzin Yundung, and Timothé Chételat for their valuable research assistance. We want to thank the editors of the Journal of Public Policy and the reviewers for their suggestions that helped to improve this article. This article is also benefited from the comments of Aaron Smith-Walter and other participants in the panel Policy Narratives and Public Policy at the 2019 International Conference on Public Policy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.