Suicide is a worldwide health concern. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 800 000 people die by suicide every year. 1 The most comprehensive review of available suicide prevention strategies was published by Mann et al in 2005 and updated by Zalsman et al in 2016. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 These reviews concluded that restricting access to lethal means prevents suicide, and that clozapine and lithium exert an anti-suicidal effect. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 However, other reviews have drawn different conclusions about the role of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions in suicide prevention. Reference Brown and Jager-Hyman4–Reference Kutcher, Wei and Behzadi12 Notably, many of these reviews rely heavily on observational data to formulate their opinions, and their conclusions are largely based on improvements in intermediary outcomes including suicidal ideation and attempts (rather than death by suicide). Reference Brown and Jager-Hyman4-Reference Kutcher, Wei and Behzadi12 These intermediate outcomes are susceptible to measurement bias and may not predict suicide. Reference Glenn and Nock13 The WHO has emphasised the critical need to identify interventions with proven efficacy for preventing death by suicide. 1 To address these concerns, we conducted a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the efficacy of various interventions versus control to prevent death by suicide in adults. We believe our review will inform clinical practice and illuminate promising areas in need of additional research, by focusing on the hard outcome of death by suicide. Reference Perlis14

Method

Review protocol

In preparation for our review, we drafted a study protocol delineating our planned approach for identifying relevant studies. We did not register our protocol with Prospero, but a copy is available in online Appendix DS1. We used the standard methodology outlined by Cochrane for our analysis and the PRISMA guidelines for reporting our methods and findings. Reference Higgins and Green15,Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman16

Eligibility criteria

We defined a priori inclusion criteria for this review. We limited our review to RCTs and pooled results of RCTs published in the English language. We required that studies randomly assign patients to an intervention aimed at suicide prevention or a control condition including usual care, placebo or wait-list. We included studies in which patients were aged 18 years or older. To broaden our search, we included studies if they reported death by suicide as a primary or secondary outcome. In the event that death by suicide was a secondary outcome, we required that the primary study aim included the prevention of suicidal ideation and/or behaviour. We included studies even if there were no suicide events because this is a more conservative approach and improves the generalisability of our findings. Reference Friedrich, Adhikari and Beyene17

We included pooled analysis of RCTs in our review. Pooled analyses, which use a systematic method to identify suicides in drug trials (e.g. US Food and Drug Administration summary basis of approval reports), may offer unique insights into the relationship between suicide and psychiatric medications. Because it is currently unclear which interventions prevent suicide, we excluded RCTs that compared two or more active treatments. Instead, we provided a qualitative summary of these trials in online Appendix DS2.

We acknowledge that there are inherent challenges in using RCTs to study rare outcomes such as suicide and that non-randomised, controlled studies may provide important information about strategies to prevent suicide. We focused our review on RCTs, however, because this study design is the gold standard for establishing efficacy, and a sufficient number of RCTs have explored suicide prevention. Reference Rosen, Manor, Engelhard and Zucker18

Study identification

We searched EMBASE, Medline, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO from the inception of each database until 31 December 2015 to identify published articles addressing our research question. We used exploded MeSH terms and key words to generate the following themes: death by suicide, prevention/control and treatment. We used ‘OR’ to combine prevention/control and treatment. We then used the Boolean term ‘AND’ to find the intersection between this collective theme and death by suicide. We applied a highly sensitive search strategy to identify RCTs in electronic databases. The details of the search strategy are available in online Appendix DS1.

We attempted to locate additional published and unpublished studies by searching ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to 31 December 2015 and reviewing the references of prior review papers and included articles. When necessary, we contacted investigators to determine whether an eligible study met our inclusion criteria (online supplemental references35–43). In the event that authors did not respond to our requests, we excluded these studies (online supplemental references40–43).

Primary end-point and data abstraction

We defined death by suicide using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition, ‘death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of the behavior.’ 19

Based on a priori inclusion criteria, two reviewers (N.B.V.R. and B.S.) screened the titles and abstracts of all potentially relevant studies. The same reviewers then assessed the full text of the remaining studies to make a final determination regarding eligibility for review. In the event that it was unclear whether a full text met all eligibility criteria, a separate reviewer (B.V.W. independently evaluated these texts for study inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Using a piloted, standardised data collection form, two reviewers (N.B.V.R. and B.S.) extracted data in duplicate from included studies. We extracted data related to demographics, methods, outcomes and risk of bias. We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool to assess study quality. Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman20 In the case of multiple reports of the same data-sets (online supplemental references35,36,38,44–72), we selected the study that included the most comprehensive and up-to-date information (online supplemental references36,60–65,67–72). From pooled analysis, we extracted total number of suicides and person-years of exposure (number of patients at risk multiplied by the number of years of exposure). To minimise bias, we preferentially selected pooled analyses that limited their analysis to the double-blind period and reported person-year exposure. We reviewed pooled analysis to ensure that trials were not double counted. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Data analysis

We evaluated our primary outcome using the Peto method and calculated summary odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals and P-values. Reference Higgins and Green21 More commonly used meta-analysis methods (e.g. risk ratio) are generally not recommended for the evaluation of rare outcomes such as suicide. Reference Higgins and Green21–Reference Lane23 The Peto method is a powerful alternative for combining data when event rates are below 1%. Reference Higgins and Green21–Reference Lane23 We did not apply a continuity correction for trials with zero events because this is not recommended with the Peto method. Reference Friedrich, Adhikari and Beyene17

We formed groups and subgroups of strategies using Mann et al's conceptual framework of suicide prevention–intervention domains and sub-domains. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2 Several interventions included in our review were not described by Mann et al (i.e. non-cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), case management, letter/telephone contact after a suicide attempt, higher-level care interventions, mood stabilisers, somatic therapies and other classes of antidepressants). Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2 Therefore, we used consensus among the authors to develop additional domains and sub-domains to categorise these interventions. Furthermore, we excluded two domains reported in Mann et al's review (screening for patients at high risk, and media reporting guidelines for suicide), because we found no related RCTs that met our inclusion criteria. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2

To promote homogeneity, we stratified each of the intervention domains based on the targeted population of interest (e.g. patients with schizophrenia). For each domain, we evaluated whether the intervention or control was favoured in each study and we then determined whether these results were statistically significant. We then evaluated the effect of combining these studies on the magnitude, direction and statistical significance of the overall summary estimate of the effect size.

We used the standard definition of an OR to interpret our results (i.e. probability of an event occurring versus the probability that the event will not occur in the intervention versus the control). We deemed that an OR less than one meant that the relative odds of death by suicide was smaller in the intervention versus the control, and the opposite was true if the OR was greater than one. Reference Szumilas24 We considered OR to be statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval did not cross one.

We used RevMan 5.3 to pool our results. 25 We assessed groupings for heterogeneity using Cochrane's Q and the I 2 statistic. Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green22 We used a conventional threshold of P<0.10 and I 2>50% to indicate statistical significance and meaningful heterogeneity, respectively. Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green22

Confirmatory analysis

Many concerns have been raised about the validity of available methods for conducting meta-analysis of rare events such as suicide. Reference Shuster and Walker26 To address these concerns, we felt that it was appropriate to perform a confirmatory analysis. We used a Poisson regression model with random effects and calculated an incidence rate ratio (IRR) for suicides over person-year for each domain of strategies. This approach accounts for differences in exposure time across studies, addresses any potential heterogeneity between trials and better accounts for trials with zero events. Reference Cai, Parast and Ryan27,Reference Spittal, Pirkis and Gurrin28 The Poisson regression model with random intervention effects has also been used in meta-analysis of rare event data, including suicide. Reference Cai, Parast and Ryan27,Reference Spittal, Pirkis and Gurrin28 However, because the Poisson regression model is not recommended if there is over-dispersion in the data, we first performed a boundary likelihood-ratio test, evaluating whether the alpha (the estimate of the dispersion parameter) for domains (and sub-domains) of interest was significantly greater than zero (defined as P<0.05). Reference Hilbe29 If we encountered significant over-dispersion, we calculated the IRR using the recommended multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial regression rather than the Poisson regression. 30 Confirmatory analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software version 14 (StataCorp).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis based on the quality of included studies as judged by the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman20 We evaluated whether the magnitude and direction of the summary estimate of each intervention domain changed if we excluded studies that were judged to be at high risk of bias.

Assessment of reporting bias

Using STATA, we generated funnel plots for domains that included at least ten studies, and we assessed for publication bias using Harbord's modified test for small-study effects. Reference Harbord, Egger and Sterne31 This method uses a modified linear regression analysis to identify significant funnel plot asymmetry which would indicate publication bias. Reference Harbord, Egger and Sterne31 The Harbord method is more powerful in cases of few events per trial. Reference Harbord, Egger and Sterne31 We considered a P<0.05 to suggest publication bias.

Results

As shown in Fig. 1, we identified 8634 records eligible for screening. After title and abstract screening, we found that 351 records remained, and 97 reports (78 studies) met inclusion criteria based on full text review (online supplemental references36,60–65,67–137).

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

Tables 1, 2 and 3 display the characteristics of included studies, which spanned five decades. Over 50% were published in the past 10 years. Although most trials studied interventions targeted at individuals with known risk factors for suicide, some trials evaluated interventions in a general or primary care population. For example, one trial investigated a central storage facility for pesticides in villages practising floriculture in Southern India (online supplemental reference94). Except for one trial that used a wait-list control and one trial that used sham (online supplemental references96,136), all trials of non-pharmacological interventions used a usual care comparison. Pharmacological studies used pill placebo as a control group.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies: complex psychosocial interventions a

| Years covered |

Study N |

Intervention N |

Control N |

Age, years: mean (s.d.) |

Female, n (%) |

Setting, Europe: n (%) |

Follow-up, months: median (IQR) |

Attrition %, median (IQR) |

Rigour in data collection b |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case management – psychosis | 1996–2007 | 4 | 771 | 774 | 33.1 (11.4) | 623 (61) | 4 (100) | 35 (25) | 4 (11) | B |

| Intensive follow-up | 1992–2015 | 11 | 2447 | 2613 | 39.4 (15.2) | 2868 (56) | 5 (46) | 12 (3) | 16 (19) | A |

| Aftercare strategy | 1989 | 1 | 68 | 73 | NR | NR | 1 (100) | 12 (0) | 4(0) | B |

| Letter/telephone contact | 1976–2011 | 7 | 2863 | 2922 | 29.4 (12.6) | 3436 (62) | 4 (57) | 13 (30) | 13 (18) | A |

| PCMH integration | 2005–2010 | 3 | 1754 | 1633 | 71.0 (7.6) | 1597 (67) | 0(0) | 24 (27) | 6(4) | B |

| RN education of caregivers | 2013 | 1 | 51 | 54 | 41.0 (16.6) | 33 (54) | 0(0) | 12 (0) | 42 (0) | C |

| Follow-up with GP after SB | 2015 | 1 | 101 | 101 | 37.8 (NR) | 111 (55) | 1 (100) | 6(0) | 13 (0) | A |

| Lethal means restriction | 2013 | 1 | 4446 | 3307 | NR | 3877 (50) | 0(0) | 18 | 19 | A |

| Psychotherapies c | ||||||||||

| CBT d | 1987–2015 | 20 | 1711 | 1542 | 30.7 (11.0) | 1818 (54) | 9 (45) | 12 (14) | 19 (16) | B |

| Non-CBTd | 2001–2016 | 5 | 263 | 278 | 33.5 (10.0) | 222 (41) | 4 (80) | 18 (12) | 23 (10) | B |

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; GP, general practitioner; IQR, interquartile range; NR. not reported; PCMH, primary care mental health; RN, nurse; SB, suicidal behaviour.

a. Reported results for age, gender and drop-out are limited to those studies for which data were available.

b. Grading of suicide assessment: A: ⩾50% of trials used rigorous methods (e.g. coroner report); B: ⩾50% of trials methods were unclear; C: ⩾50% of trials methods were at risk for bias (e.g. informant).

c. Except for one trial (online CBT module to prevent suicide) which used a wait-list control (van Spijker et al; online supplemental reference96), all trials of non-pharmacological interventions used a usual care or standard care control condition.

d. A third arm of the CBT trial conducted by Tarrier et al (online supplemental reference107) evaluated supportive therapy for psychosis. This arm was included in the analysis of non-CBT therapies.

Table 2 Characteristics of included studies: pharmacological interventions a

| Years covered |

Study N |

Intervention N |

Control N |

Age, years: mean (s.d.) |

Female, n (%) |

Setting, Europe: n (%) |

Follow-up, months: median (IQR) |

Attrition %, median (IQR) |

Rigour in data collection b |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised placebo-controlled trials of medications | ||||||||||

| Antidepressants | 1982–2013 | 7 | 894 | 891 | 54.0 (16.0) | 966 (57) | 3 (43) | 3 (3) | 27 (16) | B |

| Lithium | 1973–2014 | 6 | 257 | 308 | 42.0 (10.9) | 199 (60) | 3 (50) | 12 (6) | 27 (45) | B |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | 2007 | 1 | 22 | 27 | 30.6 (NR) | 32 (65) | 1 (100) | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | B |

| Pooled analysis of randomised trials of medications | ||||||||||

| Antidepressants | 2005–2007 | 3 | 41 099 | 14944 | 43.6 (2.7) | 29378 (58) | n/a | PY median: 1367 (2086.7) | NR | B |

| Antipsychotics | 2003–2013 | 2 | 42 203 | 7042 | 41 (NR) | 15771 (37) | n/a | PY median: 3201 (4275.8) | NR | B |

| Mood stabilisers | 2005 | 1 | 2449 | 1423 | NR | NR | n/a | PY median: 730 (0) | NR | B |

IQR, interquartile range; n/a, not available; NR, not reported; PY, person-year exposure.

a. Reporteq results for age, gender and drop-out are limited to those studies for which data were available.

b. Grading of suicide assessment: A: ⩾50% of trials used rigorous methods (e.g. coroner report); B: ⩾50% of trials methods were unclear; C: ⩾50% of trials methods were at risk for bias (e.g. informant).

Table 3 Characteristics of included studies: higher-level care interventions a

| Years covered |

Study N |

Intervention N |

Control N |

Age, years: mean (s.d.) |

Female, n (%) |

Setting, Europe, n (%) |

Follow-up, months: median (IQR) |

Attrition %, median (IQR) |

Rigour in data collection b |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial hospital admission | 1999–2008 | 2 | 163 | 87 | 35.9 (10.7) | 122 (49) | 2 (100) | 15 (3) | 28 (15) | A/C |

| Special care unit | 1997 | 1 | 140 | 134 | 36.3 (15.1) | 180 (66) | 1 (100) | 12 (0) | NR | A |

| Somatic therapies | ||||||||||

| ECT | 2013 | 1 | 28 | 28 | 57 (15.8) | 28 (50) | 1 (100) | 12 (0) | 0 (0) | B |

| rTMS c | 2014 | 1 | 20 | 21 | 42.5 (15.7) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | 6 (0) | 27 (0) | B |

ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; IQR, interquartile range; NR=not reported; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

a. Reporteq results for age, gender and drop-out are limited to those studies for which data were available.

b. Grading of suicide assessment: A: ⩾50% of trials used rigorous methods (e.g. coroner report); B: ⩾50% of trials methods were unclear; C: ⩾50% of trials methods were at risk for bias (e.g. informant)

c. The comparison arm received sham rTMS.

Assessment of quality

We identified a number of methodological concerns (online Table DS1). All studies were of randomised design, but many trials had small sample sizes, large losses to follow-up, and/or were of short duration. For non-pharmacological studies, it was difficult to mask patients/personnel, and the usual care arm was not standardised across studies. Some authors raised concerns about the fidelity of the intervention. Several authors suggested that patients in the usual care arm may have benefited from study assessments, and these benefits may have obscured the true effect of the intervention. Finally, although many trials used robust methods to identify suicide, several trials relied on methods that were either unclear or at high risk for bias, which may have resulted in over- or underestimation of the true effect of the intervention. For example, Sun et al used informants (caregivers) to report suicide and suicidal behaviour, but raised concerns that information may have been withheld owing to the stigma of suicide (online supplemental references65).

Analysis of heterogeneity

As shown in online Fig. DS1, we encountered little heterogeneity in our analysis, except there was modest heterogeneity when we evaluated intensive follow-up interventions (Q = 7.17 (P = 0.05), I 2 = 48%). This reflects the distinct differences between the types of interventions tested. Reassuringly, the heterogeneity resolved when we categorised these interventions into three sub-domains.

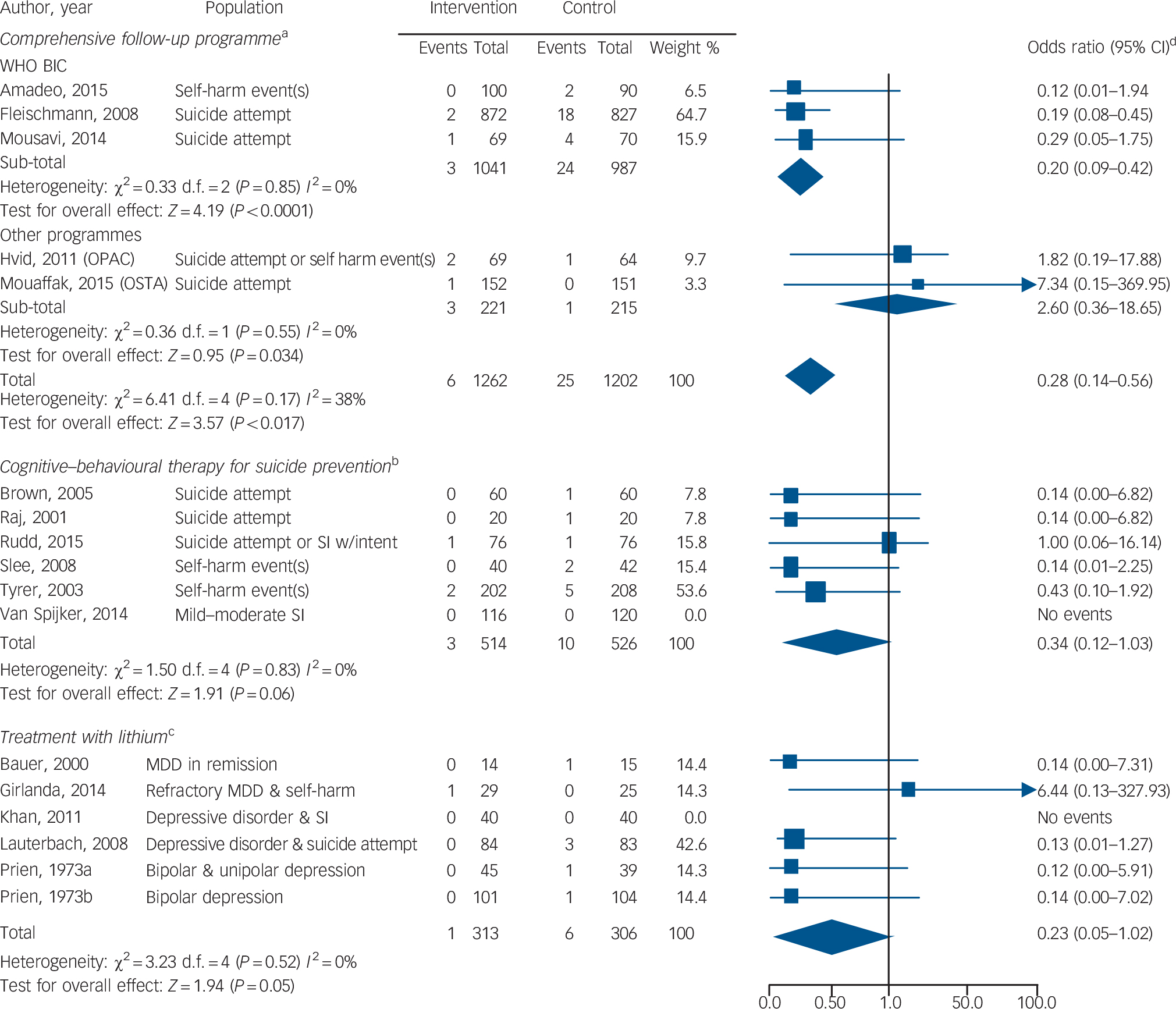

Effects of complex psychosocial interventions

Twenty-nine RCTs (n = 22 135) reported on complex psychosocial interventions (online supplemental references36,60–65,73–94). In the three trials of the WHO brief intervention and contact (BIC) intervention, 3 out of 1041 patients in the intervention group and 24 out of 987 patients in the control group died by suicide, and the difference was significant (OR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.09–0.42, P<0.0001; IRR not calculable owing to insufficient number of studies) (Fig. 2) (online supplemental references60,73–74). The WHO BIC was tested in low- and middle-income countries as part of the Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal Behaviours. The intervention included an educational session on suicide prevention followed by regular contact with a trained provider (by telephone or in person) for up to 18 months (online supplemental references60,73,74). There was no evidence that other complex psychosocial interventions reduce the risk of suicide (online Fig. DS1 and online Table DS2).

Fig. 2 Forest plots of the odds of suicide with three different targeted interventions to prevent suicide v. control condition.

MDD, major depressive disorder; OPAC, outreach, problem solving, adherence and continuity; SI, suicidal ideation; χ2, Cochrane's Q; WHO BIC, World Health Organization brief intervention and contact programme.

a. Programmes included: WHO BIC (educational intervention plus telephone or face-to-face contact with providers trained in suicide prevention), OPAC (a nurse specialising in suicide prevention was assigned to follow the patient throughout the course of the intervention), and OSTA (regular telephone and letter contact with patient plus interprofessional collaboration). Study duration ranged from 12 to 18 months.

b. Patients received between 5 and 12 sessions of the therapy intervention.

c. The study duration ranged from 1 month to 24 months.

d. The odds ratio has a skewed distribution. Although the lower end of the odds ratio is bounded by zero (an odds ratio cannot be negative), the upper end can reach infinity (online supplemental reference139).

Effects of psychotherapy

There were 24 unique RCTs (n = 3056) of psychotherapies to address suicidal behaviour (online supplemental references67,68, 95–116). In six trials of CBT for suicide prevention, 3 out of 514 patients in the intervention group and 10 out of 526 patients in the control group died by suicide (Fig. 2). The results, however, were not statistically significant (OR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.12–1.03, P = 0.06; IRR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.08–1.11, P = 0.07) (online supplemental references67,95–99). Common features of the intervention included reviewing a recent suicide attempt, applying cognitive strategies and learning relapse prevention. There was no evidence that other CBT or non-CBT therapies reduce the risk of suicide (online Fig. DS1 and online Table DS2).

Effects of pharmacotherapy

There were 14 RCTs (n = 2443) reporting on pharmacotherapy and death by suicide (online supplemental references117–130). After accounting for random effects and length of follow-up, there was no evidence among the pooled trials that pharmacotherapy reduced the risk of suicide (OR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.05–0.86; IRR = 0.10, 95% CI 0.00–32.27) (online Fig. DS1 and online Table DS2). In 6 trials of lithium, 1 out of 313 patients in the intervention group and 6 out of 306 patients in the control group died by suicide. The results, however, were not statistically significant (OR = 0.23, 95% CI 0.05–1.02, P = 0.05; IRR = 0.14, 95% CI 0.00–9.41, P>0.1) (online Fig. 2 and online Table DS2) (online supplemental references117–122). Several trials tested lithium in patients with depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviour (Fig. 2). With the exception of one trial that evaluated low-dose lithium (300 mg/day) (online supplemental references120), trials were designed to reach a target therapeutic lithium level (online supplemental references117–119,121,122). We identified no placebo-controlled trials of clozapine for suicide prevention.

A large amount of data were included in pooled analyses (6 trials, 23 016 person-years) to evaluate pharmacotherapy. The overall summary estimate yielded non-significant results (IRR = 1.15, 95% CI 0.56–2.39, P>0.10) (online supplemental references70–72,131–133), and there was insufficient granularity to compare specific pharmacotherapy agents.

Other interventions

We found no evidence that higher-level care interventions such as partial hospital admission (2 trials, n= 432; OR = 0.36, 95% CI 0.07–1.86, P>0.10) (online supplemental references69,134,135) or somatic therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy (2 trials, n= 92; OR = 0.14, 95% CI 0.00–6.82, P>0.10) (online supplemental references136,137) reduce the risk of suicide (online Fig. DS1). There were too few studies available to calculate an IRR for these interventions.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded trials that had one or more high risk for bias based on the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (online supplemental references63–65,67,69,71,72,75–82, 84,86,88–91,93,94,96,97,99,101,104–108,110–114,116,118,119,134,137) (online Table DS1). This did not change our results in a substantial way, except for our analysis of lithium trials. The results of the summary estimate for lithium became statistically significant after removing a more recent study (online supplemental references118) with several methodological limitations (5 trials; OR = 0.13, 95% CI 0.03–0.66, P = 0.01, test of heterogeneity P = 1.00 (Q = 0.01, I 2 = 0%)).

Reporting bias

We did not find any evidence to suggest publication bias among complex psychosocial interventions, psychotherapy, intensive follow-up strategies or CBT (Harbord's modified test for small-study effects; P = 0.20, P = 0.47, P = 0.57 and P = 0.71, respectively). We were unable to formally assess for publication bias among the remaining domains and sub-domains (as domains included fewer than ten studies or most of the studies in the domain reported no events).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The amount of research on suicide prevention, and specifically the number of RCTs targeting suicide, has increased substantially over the past decade. We located 56 RCTs of suicide prevention strategies in adults that have been published since Mann et al's review. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2 This suggests that more research using RCT methodology is being done in the area of suicide prevention. Although most interventions did not lead to a significant reduction in suicide, we did find that the WHO's BIC intervention was associated with significantly lower odds of death by suicide. Although trials of lithium and CBT for suicide prevention showed fewer deaths by suicide among the intervention groups than the controls, we were unable to draw any definitive conclusions, as the confidence interval for the summary estimates spanned no difference. Trials had several limitations. Most lithium trials had small sample sizes (<85 patients) and trials of CBT for suicide prevention were generally of short duration (median 10.5 months). It is also worth noting that the WHO's BIC intervention may not be generalisable to high-income countries, and that lithium was only studied in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression.

Comparison with other studies

As with a meta-analysis of findings from the most recent Cochrane review of psychosocial interventions for self-harm, we found that CBT-based therapies were associated with lower odds of suicide, but the results were not significant. Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell8 Because these authors did not perform a subgroup analysis, we cannot compare our results for CBT for suicide prevention. Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell8 Other reviews, however, have suggested that CBT for suicide prevention may prevent suicidal behaviour in high-risk populations. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Brown and Jager-Hyman4 Unlike prior reviews, we found no evidence that problem-solving therapy or dialectical behaviour therapy reduce the risk of suicide. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 Our differing conclusions may reflect our focus on suicide deaths, rather than on intermediary outcomes.

Consistent with others, we found that most psychosocial interventions were ineffective, Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 but we differed from Milner et al Reference Milner, Carter, Pirkis, Robinson and Spittal6 in that we found no evidence to support letter/telephone-driven interventions. We believe the divergence in our results may reflect our decision to evaluate postcard/telephone interventions and intensive follow-up strategies separately. Reference Milner, Carter, Pirkis, Robinson and Spittal6 Furthermore, unlike Mann et al Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2 and Zalsman et al, Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 we felt that there was strong evidence that the WHO BIC programme was associated with significantly lower odds of suicide. Our divergent conclusions may reflect our inclusion of two additional RCTs and our focus on death by suicide rather than on intermediary outcomes. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 Recently, Inagaki et al also reported that intensive follow-up significantly reduced suicides. Reference Inagaki, Kawashima, Kawanishi, Yonemoto, Sugimoto and Furuno7 These authors, however, did not specifically evaluate the WHO BIC programme. Reference Inagaki, Kawashima, Kawanishi, Yonemoto, Sugimoto and Furuno7

Akin to our results, a Cochrane review concluded that there is an insufficient number of high-quality trials available to draw any firm conclusions about the role of medications in patients who self-harm. Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell5 Although Zalsman et al reported that antidepressants reduced the risk of suicide in adults, Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 we did not replicate this finding. The majority of RCTs of antidepressants included in our review reported no suicides. In addition, unlike previous reviews, Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 we did not find that lithium significantly reduced suicide. This may be explained by our inclusion of a recent RCT with negative findings (online supplemental reference118). Furthermore, although Mann et al Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2 and Zalsman et al Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 concluded that clozapine has an anti-suicidal effect, we did not replicate this finding. This difference may reflect our decision to limit our review to placebo-controlled trials. We located no placebo-controlled trials of clozapine for suicide prevention. We also focused our review on suicide deaths, rather than on intermediary outcomes. Furthermore, prior reviews have relied heavily on the results of the InterSePT study to support clozapine's anti-suicidal effect (online supplemental reference138). Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2 We excluded the InterSePT study because clozapine was compared with olanzapine (online supplemental reference138) rather than placebo. It is notable, however, that the InterSePT study reported a higher number of suicide deaths in the clozapine arm versus olanzapine, although the results were not significant (online supplemental reference138). Others have also raised concerns about the lack of strong evidence to support clozapine's anti-suicidal effect. Reference Baethge32,Reference Lobos, Komossa, Rummel-Kluge, Hunger, Schmid and Schwarz33

Although many reviews stress the role of restricting access to lethal methods in suicide prevention, Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 we were unable to systematically study this type of intervention because only one study met our inclusion criteria. Restricting access to lethal means such as gun control is not easily tested under randomised conditions, although a plethora of observational data have demonstrated that restricting access to lethal means can prevent suicide. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas2,Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 Finally, Zalsman et al concluded that other strategies such as screening programmes and media education required more testing. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, Van Heeringen, Arensman and Sarchiapone3 We were unable to assess these strategies because no studies met our inclusion criteria.

Meaning and implications of the review

The WHO BIC intervention was associated with significantly lower odds of suicide, but it will be important to test this strategy in other populations. Although the summary estimates for CBT for suicide prevention and lithium showed fewer deaths by suicide among the intervention group than the control group, the results were not statistically significant. Therefore, we believe our results should be interpreted with caution. Reference Wood, Freemantle, King and Nazareth34 Our findings do not suggest that lithium or CBT for suicide prevention cause harm, but they also do not provide clear evidence of effectiveness. Our findings suggest the need for further study of these interventions.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

We performed a rigorous search of the literature and did not exclude studies based on quality or relevance. This has been a criticism of the Zalsman review. Reference Kutcher and Wei35 Although our focus on death by suicide can be viewed as a strength, Reference Perlis14,Reference Kutcher and Wei35 it is also a potential limitation. Reference Glenn and Nock13 RCTs offer the best evidence, but there are inherent limitations in developing and testing targeted interventions to address rare events such as suicide in the context of an RCT. Reference Glenn and Nock13,Reference Rosen, Manor, Engelhard and Zucker18 Many studies were at risk for bias in their assessment of suicide, and this may have obscured the true effect. Furthermore, for many interventions there were insufficient data (i.e. limited number of trials and/or small sample sizes) to draw any definitive conclusions about their efficacy. In addition, owing to the small sample sizes, we had poor precision around the summary estimate of the effect size, further limiting our evaluation of these interventions. Since our analysis did not include patient-level data, we were unable to explore potential moderators or mediators of the efficacy of suicide prevention interventions. Peto ORs can also yield biased results when there are substantial differences in study arm sizes. Reassuringly, the comparator arms of included RCTs were well balanced. We did not calculate Peto ORs for pooled analysis because of large differences in study arms. Finally, although many novel approaches to suicide prevention (e.g. ketamine) are emerging, no studies of these met our full inclusion criteria.

Overall, our review suggests that the WHO BIC intervention is associated with significantly lower odds of suicide. Although trials of CBT for suicide prevention and lithium showed fewer deaths by suicide among the intervention groups than the controls, the differences were not statistically significant. Available studies also have several limitations that may threaten their internal and external validity. More research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of these and other interventions in a range of settings.

Funding

This work was supported by the VA National Center for Patient Safety Center of Inquiry Program (PSCI-WRJ-SHINER). B.S. is the recipient of a VA Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award ().

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Gregory McHugo, Research Professor of Community and Family Medicine, and of Psychiatry, of The Dartmouth Institute at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, for providing us with editing suggestions.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.