People with severe mental illness (SMI) consume diets that are more energy-dense, highly processed, higher in salt and contain less fruit and vegetables, compared with the general population. Reference Dipasquale, Pariante, Dazzan, Aguglia, McGuire and Mondelli1 People with SMI also engage in lower levels of physical activity, Reference Jerome, Young, Dalcin, Charleston, Anthony and Hayes2 and have higher rates of smoking and substance use. Reference Cooper, Mancuso, Borland, Slade, Galletly and Castle3,Reference Bahorik, Newhill, Queen and Eack4 Antipsychotic medications induce greatly increased hunger, decreased satiety and increased cravings for sweet foods and drinks. Reference Treuer, Hoffmann, Chen, Irimia, Ocampo and Wang5,Reference Blouin, Tremblay, Jalbert, Venables, Bouchard and Roy6 Additionally, a number of adverse eating styles have been observed, including fast-eating syndrome, disordered eating habits (e.g. only eating one main meal daily), increased consumption of junk food and low food literacy. Reference Treuer, Hoffmann, Chen, Irimia, Ocampo and Wang5–Reference Yum, Caracci and Hwang7 Although the poor physical health of people with SMI is well established, consensus on the appropriate prevention and/or treatment interventions is in evolution, with calls for increased emphasis on lifestyle interventions aimed at reducing overweight/obesity and consequent metabolic abnormalities in established SMI, Reference Bonfioli, Berti, Goss, Muraro and Burti8 and preventing these adverse health trajectories in the early stages of psychosis. Reference Curtis, Watkins, Rosenbaum, Teasdale, Kalucy and Samaras9,Reference Teasdale, Harris, Rosenbaum, Watkins, Samaras and Curtis10 The mandate for improved physical healthcare and physical health protection in severe mental illness has led to an international working group and declaration, Healthy Active Lives (HeAL), that has established goals for the prevention of cardiometabolic decline in first-episode psychosis (www.iphys.org.au). Reference Shiers and Curtis11 Strong evidence now exists for holistic lifestyle interventions, Reference Bonfioli, Berti, Goss, Muraro and Burti8 and as part of this the inclusion of physical activity interventions for people living with severe mental illness. Reference Rosenbaum, Tiedemann, Sherrington, Curtis and Ward12

Poor physical health in people experiencing SMI stems from both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors linked to the illness itself, compounded by significant medication effects. Antipsychotic medications induce rapid weight gain with associated metabolic abnormalities. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Crespo-Facorro, Hetrick, Rodriguez-Sanchez and Perez-Iglesias13,Reference Correll, Manu, Olshanskiy, Napolitano, Kane and Malhotra14 This weight gain contributes to the high rates of overweight and obesity and metabolic complications in people with established SMI, with diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia rates respectively two and five times higher than those observed in the general population. Reference Miller, Paschall and Svendsen15–Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs, Mitchell, De Hert, Wampers and Ward18 To date, the efficacy of specific components, including modes of delivery, of nutrition interventions has not been systematically evaluated. With irrefutable evidence demonstrating the crucial role of nutrition in weight management, Reference Franz, VanWormer, Crain, Boucher, Histon and Caplan19 and the prevention and treatment of metabolic disease in the general population, Reference Ajala, English and Pinkney20,Reference Yamaoka and Tango21 a comprehensive assessment of various nutrition intervention strategies employed to assist a highly vulnerable and challenging populations is a priority. The specific questions to be answered by this review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were the following.

-

(a) Do nutrition interventions improve anthropometric measures (weight, body mass index and waist circumference) and biochemical profiles (lipids, glucose and insulin) of people living with SMI?

-

(b) Do nutrition interventions improve the nutritional intake of people living with SMI?

Method

The aims and method of this systematic review and meta-analysis were registered with the PROSPERO database prior to conducting the review (CRD42014014017). Reporting was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman22

Search strategy

An electronic database search was completed from earliest record to February 2015 using Medline, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, PsycINFO and CINAHL, using key nutritional, anthropometric and psychiatric terminology. Google Scholar and relevant published systematic reviews were manually searched for additional titles. Study eligibility was assessed according to inclusion criteria by two investigators. If agreement was not established, a third investigator acted as arbitrator. Data were extracted by the two investigators and pooled for meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Trial quality was assessed using a modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist. 23 Trial characteristics were assessed across four criteria: concealed allocation, assessor masking, treatment equality between groups (excluding intervention) and accounting for all participants randomised. One point was allocated for each criterion, giving a maximum score of four.

Participants

Randomised controlled trials recruiting participants 18 years old or over meeting DSM or ICD criteria for SMI (schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar affective disorder, depression with psychotic features) were eligible for inclusion. There was no restriction on medication use.

Interventions

Studies of stand-alone nutrition interventions or nutrition interventions delivered as part of a multidisciplinary intervention were included. Interventions comprising individualised nutrition counselling, group nutrition education, shopping or cooking classes were eligible. No restriction was placed on intervention setting: interventions in in-patient services, out-patient programmes and community volunteer services or otherwise were included. The process of referral to the study, location where the intervention was delivered, and the professional background of those who delivered the intervention were recorded. No restriction was placed on intervention intensity or duration.

Outcome measures

All trials that met inclusion criteria were included in a qualitative analysis. Trials were included in the meta-analysis if they provided adequate data on anthropometric (primary outcomes: weight, body mass index and waist circumference) and biochemical and/or nutritional parameters (secondary outcomes: total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, blood glucose, insulin and dietary intake). Data collection time points included pre- and post-intervention and follow-up. Where necessary, corresponding authors of included trials were contacted to provide additional data for inclusion in the meta-analysis. A follow-up and final email was sent 3 weeks later if corresponding authors did not reply to the initial request.

Statistical analysis

Because of the anticipated heterogeneity we used a random effects meta-analysis and calculated Hedges' g and 95% confidence intervals as the effect size measure. The meta-analysis was conducted in the following stages. First, we calculated Hedges' g and the 95% CI for the primary outcome measures: weight, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference. Second, we conducted subgroup analyses to investigate differences in the primary outcomes for the main analysis according to whether interventions were delivered by a dietitian or not, and whether they were delivered at initiation of antipsychotic therapy (⩽3 months exposure to second-generation antipsychotic medication) or subsequent to antipsychotic use. For each subgroup analysis we investigated the between-subgroup difference in effect size and report the corresponding P value. Third, we conducted meta-regression analyses investigating potential moderators of the primary outcome results including the percentage of men and mean age in both control and intervention groups, percentage receiving antipsychotics, duration of intervention, the profession delivering the intervention and exercise intensity. In order to test whether the profession of the person who delivered the intervention (dietitian v. other healthcare professional) was an independent predictor of our primary outcomes from other variables (in particular, exercise participation in multimodal programmes), we conducted multivariate meta-regressions. In order to correct for multiple testing of covariates in our meta-regression, a Bonferroni correction was made and a new P value to indicate significance was set at 0.006 (0.05 divided by 8). In the next stage, we calculated Hedges' g and 95% CI for the secondary outcomes including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, blood glucose and insulin. We investigated heterogeneity with the I 2 statistic. Publication bias was assessed with a visual inspection of funnel plots and with the Begg–Mazumdar Kendall's tau and Egger bias test. Reference Begg and Mazumdar24,Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder25 If we encountered publication bias, we adjusted for this by conducting a trim and fill adjusted analysis to remove the most extreme small studies from the positive side of the funnel plot, Reference Duval and Tweedie26 and recalculated the effect size at each iteration until the funnel plot was symmetrical about the (new) effect size. All analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3.

Results

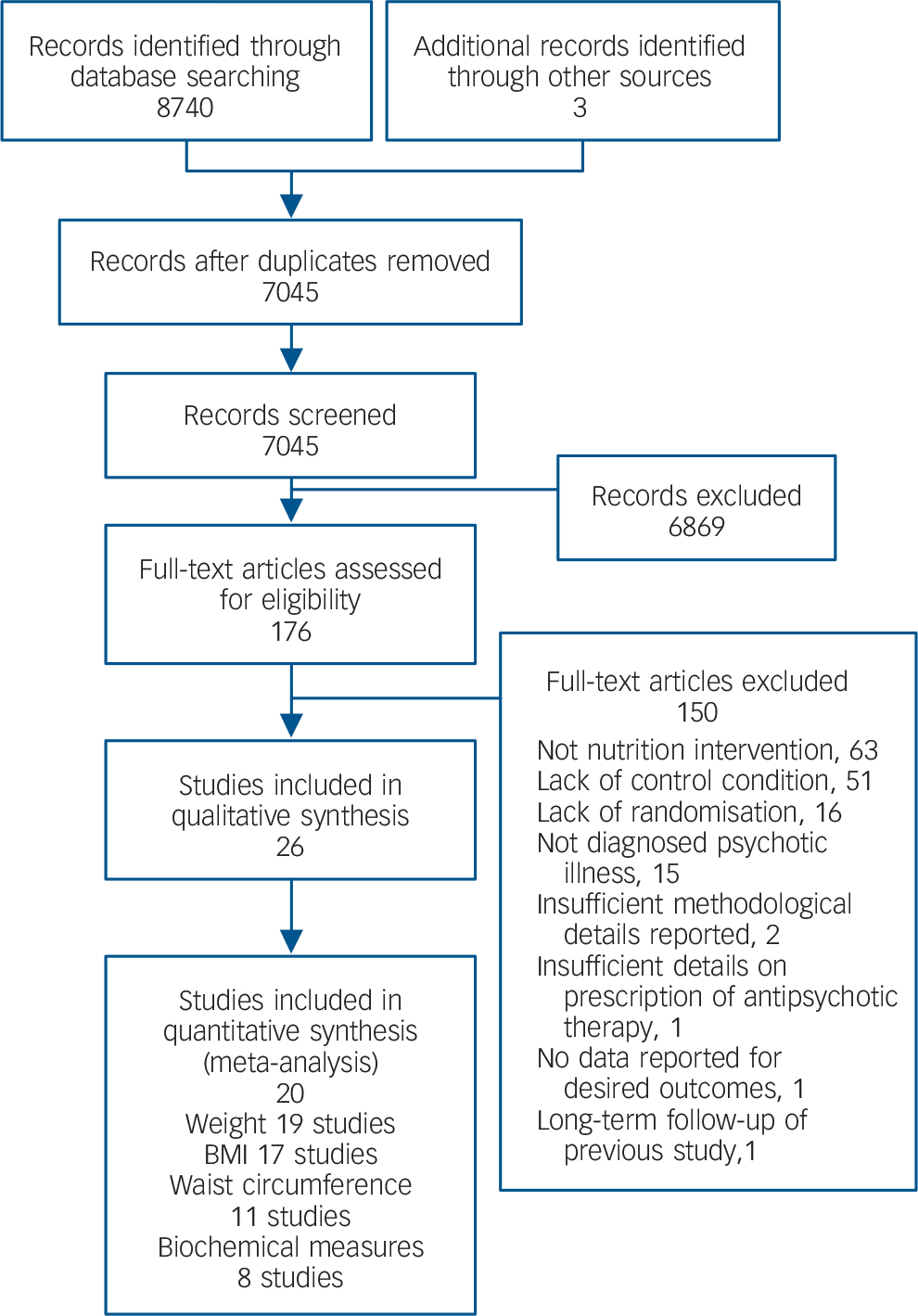

After accounting for duplicates, 7045 unique records were screened from the database searches. Full-text articles were accessed for 176 records; 150 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were subsequently excluded (Fig. 1). Twenty-six studies met the inclusion criteria, Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27–Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 but 6 studies reported incomplete data and could not be pooled for meta-analysis. Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36,Reference Jean-Baptiste, Tek, Liskov, Chakunta, Nicholls and Hassan41,Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46,Reference Milano, Grillo, Del Mastro, De Rosa, Sanseverino and Petrella48 For the primary outcomes measures, 19 studies were pooled for weight, Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27–Reference Brown, Goetz and Hamera30,Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33–Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins35,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Goldberg, Reeves, Tapscott, Medoff, Dickerson and Goldberg38,Reference Iglesias-Garcia, Toimil-Iglesias and Alonso-Villa40,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42–Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47,Reference Scocco, Longo and Caon49–Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 17 studies for BMI, Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27–Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud29,Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33–Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins35,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Iglesias-Garcia, Toimil-Iglesias and Alonso-Villa40,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42–Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50–Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 and 11 studies for waist circumference. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33–Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins35,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Iglesias-Garcia, Toimil-Iglesias and Alonso-Villa40,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50,Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 For secondary outcomes 8 studies were pooled reporting the impact of nutrition interventions on biochemical outcomes (blood pressure, lipids, glucose, insulin). Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud29,Reference Daumit, Dickerson, Wang, Dalcin, Jerome and Anderson34,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42,Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47 Measures of nutritional intake were reported in 6 studies. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Goldberg, Reeves, Tapscott, Medoff, Dickerson and Goldberg38,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44,Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46 These measures could not be pooled for quantitative analysis, but were included in qualitative analysis. Longer-term follow-up of 2 included studies was reported in separate publications. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Martinez-Garcia, Perez-Iglesias, Ramirez, Vazquez-Barquero and Crespo-Facorro53,Reference McKibbin, Golshan, Griver, Kitchen and Wykes54 Comprehensive datasets were obtained directly from corresponding authors for 2 studies. Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42

Fig. 1 Flowchart of study search. BMI, body mass index.

Characteristics of included trials

The sample size within studies ranged from n = 15 to n = 291. Mean participant age ranged from 26 years (s.d. = 15.5) to 54.8 years (s.d. = 8.2). Diagnoses within included studies were schizophrenia (18 studies), schizoaffective disorder (12 studies), schizophreniform disorder (3 studies), bipolar affective disorder (7 studies), delusional disorder (2 studies), brief reactive psychosis (2 studies), psychosis not otherwise specified (2 studies), personality disorder (2 studies), anxiety (2 studies) and depression (2 studies). First-episode psychosis, major affective illness, major depressive disorder, psychotic depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were identified in one study each. More general diagnostic descriptors were also employed in a minority of studies: SMI (4 studies), psychosis (2 studies), schizophrenia spectrum (1 study) and autism spectrum (1 study). Participants were recruited from out-patient settings (21 studies), in-patient settings (3 studies) or included a mix of out-patients and in-patients (2 studies). Characteristics of included trials are summarised in online Table DS1.

Interventions

Nutrition intervention delivery methods included individualised counselling (12 studies), group education (12 studies) and a mixture of group and individual components (2 studies). Seven studies primarily used dietitians to deliver interventions, Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33,Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins35,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42,Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference Milano, Grillo, Del Mastro, De Rosa, Sanseverino and Petrella48,Reference Scocco, Longo and Caon49,Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 with an additional 5 studies including a nutrition professional as a smaller part of the intervention primarily delivered by other clinicians. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown, Goetz and Hamera30,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Jean-Baptiste, Tek, Liskov, Chakunta, Nicholls and Hassan41,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47 Fourteen studies did not report input from a nutrition professional. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27,Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud29,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Daumit, Dickerson, Wang, Dalcin, Jerome and Anderson34,Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36,Reference Goldberg, Reeves, Tapscott, Medoff, Dickerson and Goldberg38–Reference Iglesias-Garcia, Toimil-Iglesias and Alonso-Villa40,Reference Littrell, Hilligoss, Kirshner, Petty and Johnson43,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44,Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50,Reference Weber and Wyne51 Seven studies adopted a manual-based lifestyle intervention, Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27–Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud29,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Littrell, Hilligoss, Kirshner, Petty and Johnson43,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50 predominantly delivered by mental health clinicians. Studies delivered predominantly by dietitians involved individualised assessment and intervention approaches. Other interventions included general nutrition education aimed at improving food literacy (not individualised counselling), weight management guidance and healthy-eating education. Cooking classes were reported in 4 studies. Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33,Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Jean-Baptiste, Tek, Liskov, Chakunta, Nicholls and Hassan41 One study incorporated two meal replacements per day, Reference Brown, Goetz and Hamera30 and another solely assessed the impact of providing free fruit and vegetables to participant households. Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46

All studies described strategies to alter participant behaviour, such as cue elimination, food diary/record-keeping and food sampling, although the specific behaviour change models used were more difficult to identify and interpret. Psychoeducation was described in 7 studies. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27,Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33,Reference Littrell, Hilligoss, Kirshner, Petty and Johnson43–Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference Scocco, Longo and Caon49 Cognitive–behavioural therapy was identified in 3 studies, Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud29,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42,Reference Weber and Wyne51 and social cognitive therapy in 1 study. Reference Daumit, Dickerson, Wang, Dalcin, Jerome and Anderson34 Within the cognitive framework, motivational interviewing and more generally motivational counselling/support were commonly used. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27,Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50 In addition, the ‘stages of change’ model was described in 2 studies where motivational interviewing was used. Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50 Finally, 1 study described the use of behaviour self-management therapy. Reference Daumit, Dickerson, Wang, Dalcin, Jerome and Anderson34 Psychoeducation was combined with motivational counselling/support in 3 studies. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27,Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44 Control groups received treatment as usual with or without written physical health information.

Outcome measures

Twenty-five studies assessed anthropometric measures, predominantly weight and BMI. Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27–Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47–Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 Additional measures included waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body fat percentage. Eleven studies (42%) included biochemical outcome measures, predominantly lipids (cholesterol studies and triglycerides), glucose and insulin. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33,Reference Daumit, Dickerson, Wang, Dalcin, Jerome and Anderson34,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37,Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Jean-Baptiste, Tek, Liskov, Chakunta, Nicholls and Hassan41,Reference Kwon, Choi, Bahk, Yoon Kim, Hyung Kim and Chul Shin42,Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45,Reference McKibbin, Patterson, Norman, Patrick, Jin and Roesch47,Reference Weber and Wyne51,Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 Studies including measures of nutritional intake were limited to 6 studies (25%), which recorded energy intake (kilojoules/calories), servings of food groups (such as fruit and vegetables), macro-nutrients (including fat and subgroups unsaturated and saturated fat), fibre and portion size. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Goldberg, Reeves, Tapscott, Medoff, Dickerson and Goldberg38,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44,Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46 In addition, one study used a ‘ten good food score’. Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44

Trial quality

Seven studies (27%) scored the maximum four points, Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Vazquez-Barquero, Perez-Iglesias, Martinez-Garcia and Perez-Pardal27,Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Daumit, Dickerson, Wang, Dalcin, Jerome and Anderson34,Reference Iglesias-Garcia, Toimil-Iglesias and Alonso-Villa40,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44 4 studies (15%) scored three, Reference Cordes, Thunker, Regenbrecht, Zielasek, Correll and Schmidt-Kraepelin33,Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36,Reference Usher, Park, Foster and Buettner50,Reference Weber and Wyne51 13 studies (50%) scored two, Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud29,Reference Brown, Goetz and Hamera30,Reference Gillhoff, Gaab, Emini, Maroni, Tholuck and Greil37–Reference Hjorth, Davidsen, Kilian, Pilgaard Eriksen, Jensen and Sorensen39,Reference Jean-Baptiste, Tek, Liskov, Chakunta, Nicholls and Hassan41–Reference Littrell, Hilligoss, Kirshner, Petty and Johnson43,Reference Mauri, Simoncini, Castrogiovanni, Iovieno, Cecconi and Dell'Agnello45–Reference Milano, Grillo, Del Mastro, De Rosa, Sanseverino and Petrella48,Reference Wu, Wang, Bai, Huang and Lee52 and 2 studies (8%) scored one (see online Table DS2). Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins35,Reference Scocco, Longo and Caon49 ‘Group treatment equality’ and ‘all participants being accounted for’ were reported in 25 studies (96%) and 22 studies (85%) respectively. Methodological uncertainties included ‘concealed group allocation’ and ‘assessor blinding’, described in 12 studies (46%) and 9 studies (35%) respectively.

Meta-analysis results

All the meta-analyses results including subgroup analyses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Meta-analysis of primary, secondary and subgroup outcomes

| Meta-analysis of mean differences | Meta-analysis of Hedges' g | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | Number of RCTs |

Mean difference |

95% CI | P a | Between-group P a |

Hedges' g | 95% CI | P a | Between-group P a |

Heterogeneity I 2 (%) |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 19 | −2.706 | −3.347 to −2.064 | <0.001 | −0.388 | −0.563 to −0.214 | <0.001 | 55 | ||

| Stage of antipsychotics | 0.70 | 0.27 | ||||||||

| At antipsychotic initiation | 4 | −2.948 | −4.381 to −1.515 | <0.001 | −0.613 | −1.051 to −0.175 | 0.006 | 34 | ||

| Subsequent to antipsychotic use | 15 | −2.639 | −3.396 to −1.883 | <0.001 | −0.345 | −0.533 to −0.158 | <0.001 | 57 | ||

| Delivered by | 0.02 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Dietitian/nutrition professional | 6 | −3.577 | −4.560 to −2.594 | <0.001 | −0.904 | −1.217 to −0.577 | <0.001 | 48 | ||

| Other healthcare professional | 13 | −2.060 | −2.906 to −1.214 | <0.001 | −0.233 | −0.379 to −0.088 | 0.002 | 8 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17 | −0.870 | −1.119 to −0.621 | <0.001 | −0.390 | −0.560 to −0.221 | 0.001 | 51 | ||

| Stage of antipsychotics | 0.73 | 0.40 | ||||||||

| At antipsychotic initiation | 3 | −0.953 | −1.506 to −0.400 | <0.001 | −0.559 | −0.986 to −0.132 | 0.01 | 66 | ||

| Subsequent to antipsychotic use | 14 | −0.843 | −1.136 to −0.550 | <0.001 | −0.359 | −0.547 to −0.172 | <0.001 | 50 | ||

| Delivered by | 0.02 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Dietitian/nutrition professional | 5 | −1.228 | −1.589 to −0.866 | <0.001 | −0.799 | −1.106 to −0.419 | <0.001 | 69 | ||

| Other healthcare professional | 12 | −0.655 | −0.943 to −0.368 | <0.001 | −0.253 | −0.410 to −0.096 | 0.002 | 0 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 11 | −2.281 | −3.267 to −1.296 | <0.001 | −0.267 | −0.415 to −0.118 | <0.001 | 17 | ||

| Stage of antipsychotics | 0.07 | 0.41 | ||||||||

| At antipsychotic initiation | 2 | −4.189 | −6.500 to −1.878 | <0.001 | −0.532 | −0.940 to −0.124 | 0.011 | 82 | ||

| Subsequent to antipsychotic use | 9 | −1.857 | −2.947 to −0.768 | <0.001 | −0.225 | −0.375 to −0.074 | 0.003 | 0 | ||

| Delivered by | 0.03 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Dietitian/nutrition professional | 3 | −4.223 | −6.257 to −2.189 | <0.001 | −0.575 | −0.939 to −0.211 | 0.002 | 68 | ||

| Other healthcare professional | 8 | −1.685 | −2.182 to −0.559 | 0.003 | −0.206 | −0.346 to 0.067 | 0.004 | 0 | ||

| Secondary outcome measures | ||||||||||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 7 | 0.632 | −1.857 to 3.122 | 0.619 | 0.054 | −0.179 to 0.286 | 0.651 | 54 | ||

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 6 | −1.686 | −3.603 to 0.231 | 0.08 | −0.232 | −0.500 to −0.037 | 0.091 | 61 | ||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5 | −0.473 | −0.915 to −0.030 | 0.04 | −0.372 | −0.692 to −0.053 | 0.022 | 68 | ||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 7 | −0.131 | −0.288 to 0.027 | 0.103 | −0.130 | −0.286 to 0.029 | 0.101 | 0 | ||

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 7 | −0.061 | −0.168 to 0.045 | 0.259 | −0.091 | −0.248 to 0.067 | 0.258 | 0 | ||

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 7 | −0.060 | −0.158 to 0.042 | 0.239 | −0.087 | −0.243 to 0.069 | 0.272 | 0 | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 7 | −0.116 | −0.249 to 0.018 | 0.089 | −0.146 | −0.304 to 0.011 | 0.069 | 0 | ||

| Insulin (mU/ml) | 3 | −0.880 | −2.652 to 0.892 | 0.330 | −0.195 | −0.426 to 0.035 | 0.097 | 18 | ||

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

a. After applying the Bonferroni correction, significance was set at P = 0.006, values in bold.

Primary outcomes

Pooled analysis showed that nutrition interventions were significantly more effective in reducing weight v. control (19 studies: g = −0.39, 95% CI −0.56 to −0.21, P<0.001, I 2 = 55%; Fig. 2). There was evidence of publication bias (Begg −0.41, P = 0.01; Egger −1.7, P = 0.08), whereas the Duval & Tweedie trim and fill effect size adjusting for publication bias remained similar and statistically significant (g = −0.33, 95% CI −0.44 to −0.22). Nutrition interventions also reduced BMI compared with control groups (17 studies: g = −0.39, 95% CI −0.56 to −0.22, P<0.001, I 2 = 51%) (see online Fig. DS2a). The results remained statistically significant when adjusted for publication bias in the trim and fill analysis (g = −0.34, 95% CI −0.45 to −0.23). Nutrition interventions were also effective in reducing waist circumference v. control (11 studies: g = −0.27, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.12, P<0.001, I 2 = 17%; see online Fig. DS3a). The results remained statistically significant in the trim and fill analysis (g = −0.25, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.12).

Fig. 2 Effect of nutrition interventions on weight v. control group.

Subgroup analysis: antipsychotic use

A larger effect size was found for studies delivered at the start of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy (4 studies: g = −0.61, 95% CI −1.02 to −0.18, P = 0.006, I 2 = 34%) compared with studies delivered subsequent to antipsychotic use (15 studies: g = −0.35, 95% CI −0.54 to −0.16, P<0.001, I 2 = 57%; see online Fig. DS1a). Similar results were seen for BMI (g = −0.56 v. g = −0.36) and waist circumference (g = −0.53 v. g = −0.23) (see online Figs DS2b and DS3b). Between-group differences did not reach statistical significance after applying a Bonferroni correction (Table 1).

Subgroup analysis: profession delivering intervention

Subgroup analysis investigating the effect of who delivered the nutrition intervention revealed that dietitians delivering specialised dietary interventions (6 studies: Hedges' g = −0.90, 95% CI −1.22 to −0.58, P<0.001, I 2 = 48%) had a significantly larger effect (P = 0.0005) compared with interventions predominantly delivered by other health professionals or mental health clinicians (13 studies: Hedges' g = −0.23, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.09, P = 0.002, I 2 = 8% (online Figs DS1b, DS2c and DS3c).

Meta-regression analyses

Weight

Single meta-regression analyses found that the profession delivering the intervention (dietitian v. other healthcare professional, β = −0.69, 95% CI −1.05 to −0.32, P<0.001) was a significant predictor of weight change (Table 2). Multivariate regression analysis found that profession remained a significant predictor of weight change independent of exercise (β = −0.72, 95% CI −1.06 to −0.37, P<0.001). The percentages of men in the control group (β = 0.01, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.02, P = 0.05) and in the nutrition group (β = 0.02, 95% CI −0.0 to 0.03, P = 0.01) were positive predictors of weight (i.e. more difficult to lose weight).

Table 2 Meta-regression of moderators of primary outcomes

| Moderator | β | 95% CI | P | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | ||||

| Mean age control group | 0.007 | −0.012 to 0.027 | 0.456 | 0.06 |

| Mean age nutrition group | 0.002 | −0.018 to 0.021 | 0.874 | 0.00 |

| Percentage men control group | 0.011 | 0.000 to 0.021 | 0.045* | 0.41 |

| Percentage men nutrition group | 0.015 | −0.003 to 0.026 | 0.012* | 0.67 |

| Duration of intervention | 0.003 | −0.006 to 0.012 | 0.536 | 0.00 |

| Profession delivering intervention | −0.685 | −1.050 to −0.320 | <0.001*** | 0.82 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Profession delivering intervention | −0.719 | −1.064 to −0.374 | <0.001*** | 1.00 |

| Exercise intensity | −0.180 | −0.399 to 0.040 | 0.108 | |

| BMI | ||||

| Mean age control group | 0.002 | −0.017 to 0.021 | 0.826 | 0.00 |

| Mean age nutrition group | −0.002 | −0.020 to 0.017 | 0.868 | 0.09 |

| Percentage men control group | 0.010 | −0.003 to 0.023 | 0.145 | 0.21 |

| Percentage men nutrition group | 0.009 | −0.004 to 0.022 | 0.161 | 0.20 |

| Duration of intervention | 0.003 | −0.005 to 0.011 | 0.403 | 0.00 |

| Profession delivering intervention | −0.528 | −0.896 to −0.160 | 0.005** | 0.59 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Profession delivering intervention | −0.526 | −0.848 to −0.204 | 0.001*** | 1.00 |

| Exercise intensity | −0.208 | −0.435 to 0.019 | 0.072 | |

| Waist circumference | ||||

| Mean age control group | −0.009 | −0.027 to 0.009 | 0.340 | 0.00 |

| Mean age nutrition group | −0.010 | −0.027 to 0.008 | 0.448 | 0.00 |

| Percentage men control | 0.003 | −0.014 to 0.020 | 0.742 | 0.00 |

| Percentage men nutrition group | 0.006 | −0.005 to 0.018 | 0.291 | 0.00 |

| Duration of intervention | 0.001 | −0.005 to 0.006 | 0.859 | 0.00 |

| Profession delivering intervention | −0.369 | −0.759 to 0.021 | 0.064 | 0.00 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Profession delivering intervention | −0.365 | −0.762 to −0.033 | 0.072 | 0.00 |

| Exercise intensity | 0.016 | −0.259 to 0.291 | 0.907 | |

BMI, body mass index.

* P<0.05,

** P<0.01,

*** P<0.001.

Body mass index

A dietitian-delivered intervention was a significant moderator of BMI results (β = −0.53, 95% CI −0.9 to −0.16, P = 0.005). This finding was confirmed through multivariate regression analysis and the results remained significant independent of exercise participation (β = −0.52, 95% CI −0.85 to −0.20, P = 0.001), with exercise not found to be a significant moderator (β = −0.21, 95% CI −0.44 to 0.02, P = 0.07).

Waist circumference

There was a non-significant trend for dietitian-delivered interventions to moderate waist circumference results (β = −0.37, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.02, P = 0.06). Multivariate regression analysis confirmed the trend for the profession delivering the intervention as a moderator independent of exercise intensity (β = −0.36, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.03, P = 0.072).

Secondary outcomes

The meta-analyses for the secondary outcomes are presented in Table 1. The analyses demonstrated that nutrition interventions reduced glucose (g = −0.37, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.05, P = 0.02, I 2 = 68%; online Fig. DS4); however, this was not statistically significant after applying the Bonferroni correction. Triglyceride levels (g = −0.15, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.01, P = 0.07, I 2 = 0%) were not significantly affected by nutrition interventions, although trends were evident. Other secondary outcome measures were not significant.

Impact on nutritional intake

Results for all six studies that assessed changes in nutritional intake favoured the intervention group but could not be pooled for meta-analysis owing to the varying outcomes measured. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32,Reference Goldberg, Reeves, Tapscott, Medoff, Dickerson and Goldberg38,Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44,Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46 Three studies used the Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education (DINE) to assess fat (unsaturated and saturated) and fibre intake. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28,Reference Brown and Chan31,Reference Brown and Smith32 One study providing hour-long weekly discussion groups did not find significant changes in anthropometric measures and also did not find significant changes in fat or fibre intake. Reference Attux, Martini, Elkis, Tamai, Freirias and Camargo28 Two studies delivered by keyworkers using a lifestyle manual, individually, which found small but significant improvements in anthropometric measures, found improvements in saturated fat and fibre intake, Reference Brown and Chan31 and improvements in saturated fat, fruit and vegetable intake. Reference Brown and Smith32 One study used the Block Fruit, Vegetable, and Dietary Fat Screeners to assess dietary change in an intervention providing healthy eating and weight-loss advice, delivered by research staff. Reference Goldberg, Reeves, Tapscott, Medoff, Dickerson and Goldberg38 This study did not find significant differences in dietary behaviours. A fifth study used a food frequency questionnaire, which appears validated in women in the general population; Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44 this questionnaire assessed the frequency of ten foods associated with better diet and ten foods associated with poorer diet. Individual psychoeducation and goal-setting significantly improved the score of foods associated with good diet compared with the control group, but not the score of foods associated with poorer diet. Reference Lovell, Wearden, Bradshaw, Tomenson, Pedley and Davies44 Finally, one trial involved using the Scottish Health Survey to assess whether providing free fruit and vegetables to families improved nutritional intake. Reference McCreadie, Kelly, Connolly, Williams, Baxter and Lean46 Although improvements in fruit and vegetable intake were found, these were not sustained after the trial – and subsequent access to free fruit and vegetables – had ceased.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review to assess the impact of key components that comprise, and modes of delivery of, nutrition interventions on physical health measures of people with severe mental illness. We found that nutrition interventions improved anthropometric measures by reducing weight, BMI and waist circumference. Importantly, our review provides evidence about the most effective goals and delivery methods, including preventing weight gain from the initiation of antipsychotic therapy and the use of qualified health professionals such as dietitians to deliver individualised interventions. Our results indicated that nutrition interventions were most effective when delivered by a dietitian, with meta-regression analyses confirming this in multivariate models. These findings show a clear and important role for dietitians as part of the multidisciplinary mental health team.

Although the overall effect size for anthropometric measures was within the small to moderate range, it provided further evidence to support implementation of lifestyle interventions. Although between-group differences did not reach statistical significance, the larger effect size (g = −0.61) seen in a pooled analysis of studies providing intervention in the early stages of antipsychotic therapy, where weight gain is most rapid, Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gonzalez-Blanch, Crespo-Facorro, Hetrick, Rodriguez-Sanchez and Perez-Iglesias13 provides evidence for the achievability of goal 5 of the Healthy Active Lives declaration – that is, to restrict weight gain to no more than 7% of pre-illness weight in 75% of people experiencing first-episode psychosis, 2 years after commencing antipsychotic treatment. Reference Shiers and Curtis11 Targeting interventions to coincide with initiation of antipsychotic therapy is also warranted given the clinical benefits of preventing significant weight gain and metabolic deterioration. Given the large effect size (g = −0.90) found for key anthropometric outcomes, nutrition interventions delivered by dietitians, in particular individualised counselling sessions, should have a central role in addressing cardiometabolic abnormalities and premature mortality in people with SMI. Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs, Mitchell, De Hert, Wampers and Ward18,Reference Walker, McGee and Druss55

It was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis on nutritional intake owing to a lack of consensus on data collection methods together with the wide variety of outcome measures used. Nutritional intake can be notoriously difficult to assess accurately because of intake variability and the wide range of nutrients to consider, particularly if the assessment method is not targeted to the specific population. To date, there is no validated nutrition assessment tool developed for use in people living with severe mental illness, a significant gap in the literature requiring urgent attention. In addition, improvements in cardiometabolic health as a result of changes in nutritional intake, independent of weight change, have not been assessed in this population. This is a significant area requiring research, given the enduring weight challenges in this population.

Our results are broadly similar to previous non-pharmacological and physical activity intervention analyses completed by Álvarez-Jiménez et al, Bruins et al and Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Tiedemann, Sherrington, Curtis and Ward12,Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Hetrick, Gonzalez-Blanch, Gleeson and McGorry56,Reference Bruins, Jorg, Bruggeman, Slooff, Corpeleijn and Pijnenborg57 Effect sizes (ES) from these analyses on anthropometric measures were respectively Z = 7.85, ES = 0.63 and standardised mean difference = 0.24. However, ours is the first review to consider the impact of nutrition interventions and provides further recommendations for dietitian-led interventions incorporated from the early stages in SMI. As with the general population, nutrition interventions are most likely to be effective when combined with physical activity.

Limitations and future research

Several factors may have influenced the results obtained by this review, largely reflecting limitations in the primary studies. First, nutrition interventions were often delivered as part of a comprehensive lifestyle programme, thus participants were potentially receiving concomitant additional lifestyle interventions such as physical activity, which may have had a synergistic effect on participant outcomes. Although it was not possible to separate the impact of the nutrition intervention from additional components, we attempted to investigate the impact of nutrition interventions through a series of adjustments for potential confounders. For instance, for the primary outcome, our multivariate meta-regression analyses consistently demonstrated that nutrition interventions were most effective when delivered by a dietitian, even when we adjusted for concomitant exercise elements. Although the results from our subgroup analyses consistently demonstrated higher effect sizes of dietitian-led nutrition interventions and interventions delivered at antipsychotic initiation, these findings did not reach statistical significance after applying the Bonferroni correction. Although Bonferroni corrections are not routinely used in meta-analyses, Reference Higgins and Green58 we have opted for a conservative approach, and although our findings did not reach significance, they suggest more favourable outcomes and warrant further investigation. Second, the RCTs included a range of nutrition interventions including group education, individualised plans, practical shopping and cooking sessions and meal replacements. Subgroup analyses were run where possible, but were limited by the small numbers of studies and highly variable methods. Future research should seek to establish homogeneity in the use of appropriate outcome measures and nutrition interventions. Third, the potential for significant effects on relevant biochemical measures may have been affected by the short duration of interventions in many studies and the target outcomes frequently being limited to anthropometric measures. Future long-term studies encompassing specific dietary strategies to target dyslipidaemia are required, with adequate follow-up to see the impact of nutrition interventions in this population. Reference Huang, Frohlich and Ignaszewski59 Fourth, we did encounter some evidence of publication bias, but after recalculating the effect sizes using Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill method our results were broadly similar. Reference Duval and Tweedie26 Fifth, we did encounter moderate heterogeneity in some of our analyses. Nonetheless, our multivariate meta-regression analyses explained all (R 2 = 1.0) of the observed heterogeneity for weight and BMI meta-analyses results. We were, however, unable to explain the heterogeneity in waist circumference; high levels of variability and inaccuracies in waist circumference measuring may be a factor. Reference Panoulas, Ahmad, Fazal, Kassamall, Nightingale and Gitas60 Finally, we were unable to access data from some of the identified studies, reducing the number of studies included and sample sizes included in some of the meta-analyses. In addition, some studies did not clearly identify the specific psychiatric diagnoses of participants, limiting the ability to draw further conclusions regarding the potential impact of diagnosis on the intervention outcomes obtained.

Nevertheless, allowing for these caveats, the results of this meta-analysis offer hope to clinical teams and patients alike that providing nutrition interventions as part of a wider multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention can be effective in preventing weight gain, particularly when delivered by a dietitian. University dietetic programmes will also need to evolve to increase the knowledge and understanding of SMI.

Study implications

Nutritional intake is fundamental to weight management and future physical health. This systematic review and meta-analysis found that nutrition interventions significantly improved weight, BMI, waist circumference and glucose levels in people with SMI. Further, nutrition interventions delivered by dietitians, and those aiming to prevent weight gain at antipsychotic initiation had the largest effect sizes. The evidence supports the early inclusion of nutrition intervention in mental health service delivery to people with SMI. Further RCTs are required to determine the most effective nutrition intervention to optimise weight and cardiometabolic health in people with SMI.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.