Introduction

In the last decades, the topic of older adults’ sexuality has become prominent (Kleinstäuber, Reference Kleinstäuber2017). In response to previously dominant constructions of older adults as ‘asexual’ or ‘sexless’, a notable part of recent research on sex in later life investigated the potentially beneficial role of maintaining sexual activity on good health and relationship wellbeing (Gott and Hinchliff, Reference Gott and Hinchliff2003; Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015; Thorpe et al., Reference Thorpe, Fileborn, Hawkes, Pitts and Minichiello2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nazroo, O'Connor, Blake and Pendleton2016; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Stelle and Bell2017). Qualitative research has shown that the majority of older adults value sexual activity, believing that it helps in remaining vital, despite the process of ageing – which has been termed as the ‘fighting ageing through sex’ attitude (Hinchliff and Gott, Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008; Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon, Reference Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon2019). In addition, sexual activity is sometimes presented as a way of fighting loneliness or, in the case of partnered older people, as means to maintain, and even improve, the relationship (DeLamater et al., Reference DeLamater, Koepsel and Johnson2019; Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon, Reference Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon2019). Continuing sexual activity in later life can also be a way to distance oneself from ‘the stereotypical portrayal of an [older] person with an illness, a physical dysfunction, and a dependence on the others’ (Ševčíková and Sedláková, Reference Ševčíková and Sedláková2020: 977). These findings implicitly suggest that sexually inactive older individuals may feel lonely, old and unattractive, are of poor health, or unconcerned with the deteriorating bond with their partner.

Despite these findings, quantitative studies show that a notable percentage of women and men report ceasing sexual activity in later life. This study aimed to explore older adults’ motives behind this, to deepen the scientific understanding of factors potentially associated with continuing or discontinuing sex among the ageing population. Guided by the assumption that some people may not consider the cessation of their sex life in negative terms, the findings presented here are based on the analysis of qualitative interviews with older women and are focused on affirmative narratives on their sexual inactivity. Specifically, this study is meant to investigate psychological, relational and societal factors which may lead some older individuals with a traditional socio-cultural background to accepting or even enjoying discontinuing their sex life at some point. Particular attention is paid to the societal sexual scripts revealed in the participants’ narratives.

Sexual inactivity in later life – undesirable necessity or a welcomed path?

The number of older adults reporting discontinuing sexual activity varies greatly between genders, age groups and studies, partially due to different operational definitions of sexual activity (from sexual intercourse to various forms of partnered and solo sexual activity) (Nicolosi et al., Reference Nicolosi, Buvat, Glasser, Hartmann, Laumann and Gingell2006; Træen et al., Reference Træen, Štulhofer, Janssen, Carvalheira, Hald, Lange and Graham2019). In a large multi-country study of sexual attitudes and behaviours in individuals aged 70–80, 46 per cent of men and 79 per cent of women reported not having had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months (Nicolosi et al., Reference Nicolosi, Buvat, Glasser, Hartmann, Laumann and Gingell2006). Other studies have found that among participants aged 65–75, 35–60 per cent of men and 45–75 per cent of women had not had any kind of sexual activity in the past year (see Træen et al., Reference Træen, Štulhofer, Janssen, Carvalheira, Hald, Lange and Graham2019). Similarly, in a national probability sample in the United States of America, 14 per cent of men and 39 per cent of women aged 55–64 years reported not being sexually active (in the past six months), but the proportions were substantially higher (38 and 64%, respectively) in the 65–74 age group (Lindau and Gavrilova, Reference Lindau and Gavrilova2010). Frequency of masturbation also decreases with age. The last British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL-3) established that over half of men aged 55–64 and only one-third of men aged 65–74 reported masturbating in the previous four weeks; for women, the proportion was one in five and one in ten, respectively (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Tanton, Prah, Erens, Sonnenberg, Clifton, Macdowall, Lewis, Field, Datta, Copas, Phelps, Wellings and Johnson2013). According to a recent cross-cultural European study (Træen et al., Reference Træen, Štulhofer, Janssen, Carvalheira, Hald, Lange and Graham2019), 35–58 per cent of male and 60–73 per cent of female participants aged 60–75 declared not masturbating in the last month. Overall, sexual inactivity appears more common with age (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson, O'Muircheartaigh and Waite2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nazroo, O'Connor, Blake and Pendleton2016).

Several factors leading to sexual inactivity in older age have been well-documented. Lack of a partner was found to be the strongest predictor of sexual activity cessation, particularly for older women (Træen et al., Reference Træen, Hald, Graham, Enzlin, Janssen, Kvalem, Carvalheira and Štulhofer2017). Increasingly common with ageing, declining partner's or personal health was also repeatedly reported (Gott and Hinchliff, Reference Gott and Hinchliff2003; Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson, O'Muircheartaigh and Waite2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nazroo, O'Connor, Blake and Pendleton2016; Tetley et al., Reference Tetley, Lee, Nazroo and Hinchliff2018). When considering gender differences, ageing women typically report partner-related reasons for sexual inactivity (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson, O'Muircheartaigh and Waite2007; Hinchliff et al., Reference Hinchliff, Gott and Ingleton2010; Tetley et al., Reference Tetley, Lee, Nazroo and Hinchliff2018; DeLamater et al., Reference DeLamater, Koepsel and Johnson2019), while men are more likely to attribute their inactivity to personal health-related reasons (Beckman et al., Reference Beckman, Waern, Gustafson and Skoog2008; Schick et al., Reference Schick, Herbenick, Reece, Sanders, Dodge, Middlestadt and Fortenberry2010; Tetley et al., Reference Tetley, Lee, Nazroo and Hinchliff2018). Relationship factors (e.g. duration or quality of a relation, level of marital happiness) are also known to impact older partnered adults’ sex life (Karraker and DeLamater, Reference Karraker and DeLamater2013). Sex negative attitudes (sexual ageism) shared by older adults or others around them (e.g. their family, friends, health-care professionals) are also associated with discontinuation of sexual activity or with experiencing various types of challenges in expressing one's sexual desires (Bradway and Beard, Reference Bradway and Beard2015; see also DeLamater, Reference DeLamater2012; Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon, Reference Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon2019). Several quantitative studies found that positive attitudes towards sex are significant predictors of sexual intercourse among older adults (Kontula and Haavio-Mannila, Reference Kontula and Haavio-Mannila2009; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Træen and Hald2021).

However diverse, the range of factors described may not represent all relevant cases and leave some older adults’ experiences unaddressed. A recent cross-cultural study that investigated reasons for sexual avoidance, defined as ‘an active decision to refrain from sexual activity’ (Carvalheira et al., Reference Carvalheira, Graham, Štulhofer and Træen2020: 175), reported an unexpected finding. Offered a set of possible reasons for sexual avoidance (relationship problems, worries about sexually transmitted infections, own or partner's sexual difficulties, health problems, etc.), a substantial number of older participants (31% of women, 24% of men) marked ‘other reasons’ as their answer, leaving the researchers to question their assumptions. The authors noted this as a limitation of their study and called for qualitative research to understand the phenomenon better (Carvalheira et al., Reference Carvalheira, Graham, Štulhofer and Træen2020: 181–182).

Recent research tends to approach the reasons for sexual inactivity in later life with the assumption that people want to be sexually active. It may be true for many older adults, and it is a reasonable counter-narrative considering that older individuals have been previously constructed as almost solely sexless. Is there, however, a possibility that some older people may actually prefer to be sexually inactive and enjoy it? Lagana and Maciel (Reference Lagana and Maciel2010), who investigated sexual desire among older Mexican-American women, reported that some of them expressed no wish to continue being sexual . Those women either considered it as part of ageing – suggesting the acceptance of the ‘asexual old age’ script – or provided other psychological or socio-cultural reasons for their lack of interest in sex. Some referred to negative past experiences with men, others reported marital discord, lack of a suitable sexual partner or a repulsion towards sexual activity in general (Lagana and Maciel, Reference Lagana and Maciel2010). In a study on sexual wellbeing among middle-aged and older Americans (Syme et al., Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019), a number of participants reported feeling well about their sexual inactivity. Moreover, some female participants voiced that having erotic memories and/or sexual fantasies, but no sex, was completely satisfying (Syme et al., Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019). The narratives of Australian single women aged 55+ on sex and dating revealed that many of them valued their own independence over sex and intimacy attainable within a relationship, declaring themselves to be ‘single by choice’, although still experiencing downsides of being without a partner (Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015: 74). The authors identified that sexual norms, ‘past relationship experiences, and the social and political context in which [the participants] came of age’ were likely to shape older single women's attitudes towards their relationship status in later life (Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015: 70). In another study, after interpreting reported lack of sexual desire in later life as a coping mechanism, Ayalon et al. (Reference Ayalon, Gewirtz-Meydan and Levkovich2019: 58) noted that an alternative is also possible: ‘moving away from the current model of sexual functioning in old age as a “must” also means that some older adults may simply resign to indifference toward or no interest in sex’. Similarly, Carvalheira et al. (Reference Carvalheira, Graham, Štulhofer and Træen2020: 183) concluded that it should ‘not be assumed that sexual activity will be the preferred choice for all older individuals’; welcoming sexual inactivity may be – in certain cases – an adaptive and positively self-evaluated behaviour.

Some qualitative findings provide insights on the diversity in lived experience of older adults, which are valuable in understanding the subtlety of continuing or ceasing sex in later life. In a study on the importance of sex for British women aged 50 or over, Hinchliff and Gott (Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008) present women's sexual discourses as simultaneously concurring and opposing the ‘asexual old age’ stereotype. Their findings revealed a sense of sexual agency exercised in deciding when and how to fulfil participants’ sexual needs, therefore negotiating their sexuality between the societal constructions of sexless old age on one side, and sex as crucial for staying healthy and feeling young on the other side. Thorpe (Reference Thorpe2019: 970), who explored how the diverse sexual pasts of older Australian women affect their later-life sexual subjectivities, unfolded the tensions between societal expectations and ‘the often contradictory ways in which being old and sexual is given meaning in women's everyday life’. Drawing on the expected effects of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, Thorpe's interviewees shared narratives on transgressing restrictive social roles in sexual and relational domains, but also narratives on not being able to do so, e.g. maintaining the traditional, normative understanding of sex as partnered, heterosexual intercourse. Some of the Australian women whose self-awareness regarding sexual desire and needs increased in later life ‘noted that their heterosexual relationships in older age were sexually disappointing or difficult to find’ (Thorpe, Reference Thorpe2019: 982), which – together with negative sexual experiences in the past voiced by other participants – left some of them with rather ambivalent attitudes towards casual sex or new relationships in later life. Another Australian study on older adults’ emotions associated with changes in their sex life captured accounts of ‘being comfortable in my own skin’, understood as the sense of sexual ‘freedom, confidence and agency … gained with age’ (Rowntree, Reference Rowntree2014: 154). It was expressed by participants not only in the context of feeling sexually liberated to engage in (and only) desirable sexual activity, but also in relation to choosing ‘to live alone rather than tolerate unsatisfying relationships’ (Rowntree, Reference Rowntree2014: 155). In the case of some female participants, sexual freedom was exercised in abstaining from sexual activity as a form of asserting one's desires, instead of following patriarchal norms of being expected to satisfy one's partner sexually (Rowntree, Reference Rowntree2014).

Building on the literature presented above, if we acknowledge that sexual inactivity in later life might not be merely an undesirable result of health- or partner-related barriers, but a welcomed choice stemming from a set of psychological, relational and societal factors, the shortage of scientific literature attempting to understand this phenomenon becomes obvious.

Sexual scripts and the specific socio-cultural context of Poland

The sexual script theory (Simon and Gagnon, Reference Simon and Gagnon1986) was chosen to guide the analyses and to provide the theoretical framework for this study. According to this theory, we should distinguish between three interrelated levels of sexual scripts (Simon and Gagnon, Reference Simon and Gagnon1986, Reference Simon and Gagnon2003; Montemurro, Reference Montemurro2014b): societal scenarios, interpersonal scripts and intrapsychic scripts. Societal scenarios can be understood as norms that regulate sexual behaviour within a society (e.g. appropriate sexual objects, aims, even feelings). On an interpersonal level, an individual needs to shape and adjust the material of a relevant societal scenario into a script of specific behaviour (specific sexual interaction). Intrapsychic scripting is ‘a private world of wishes and desires [which] must be bound to social life’ (Simon and Gagnon Reference Simon and Gagnon1986: 100) – the space where individual sexual desires are linked to societal meanings.

Sexual scripts are not rigid rules of sexual conduct, but rather a process of constant development, re-writing and negotiating of meanings. According to Simon and Gagnon (Reference Simon and Gagnon1986, Reference Simon and Gagnon2003), a lack of congruence between societal and personal levels of scripting is possible. They attribute it to an individual life trajectory (e.g. life events, experiences) or not enough coherence in socio-cultural expectations (e.g. contradictory societal scripts of ‘asexual old age’ and ‘sex as crucial in successful ageing’). As documented in some qualitative research, an individual's personal scripts might conform to the dominant societal norms or – if a disjuncture is too great – might evolve and go above and beyond the conventionally shared meanings (Masters et al., Reference Masters, Casey, Wells and Morrison2013; Murray, Reference Murray2018; Gore-Gorszewska, Reference Gore-Gorszewska2020). It may be particularly interesting in older adults, for whom the accumulation of life experiences along with the socio-cultural transformations that have occurred over the course of their lives have potentially presented more opportunities for sexual script change.

The distinctive socio-cultural context of Polish older adults’ sexuality stems from the post-Second World War period. Under the real-socialist regime, women were encouraged by the state to join the workforce (in the spirit of revolutionary gender equality) and, at the same time, expected to be mothers to a new generation of socialist youth (Mikołajczak and Pietrzak, Reference Mikołajczak, Pietrzak, Safdar and Kosakowska-Berezecka2015). The Polish Catholic Church cemented its sociocultural influence by becoming the main opposition to the real-socialist regime (Ediger, Reference Ediger2005; Ingbrant, Reference Ingbrant2020). Yet, in the spirit of faith-based – heteronormative and conservative – values, the Polish Catholic Church advocated, with striking similarity to the regime, that women should ‘play a vital role in society as faithful and fecund wives, whose identity revolve around their family and whose needs are the needs of their families’ (Mikołajczak and Pietrzak, Reference Mikołajczak, Pietrzak, Safdar and Kosakowska-Berezecka2015: 174). This situation did not leave much room for alternative scripts, such as the one brought about by the so-called sexual revolution in the West.

At the time when participants in the current study reached sexual maturity, the dominant cultural scenarios encouraged them to fulfil a gendered set of marital obligations, often discouraging female sexual autonomy and agency. Women's personal sexual scripts were developed and negotiated in the context of a blend of real-socialist and Catholic traditional morality, gender inequality (revolving around the notion of sex as the women's marital and procreational duty), and irrelevance of female sexual pleasure (Mikołajczak and Pietrzak, Reference Mikołajczak, Pietrzak, Safdar and Kosakowska-Berezecka2015; Ingbrant, Reference Ingbrant2020).

The current study

To the best of my knowledge, there have been no direct attempts to explore qualitatively the motives for not wanting sex in older age. As presented earlier, much of the research into sexual inactivity in older age has been informed by the understanding that older adults want to be sexually active but are often faced with substantial obstacles in this pursuit. More nuanced analyses of older adults’ complex narratives on their sexual inactivity are usually interwoven with other topics of research and draw on the experiences of older adults from Western cultures. This study, therefore, (a) seeks to build on and elaborate the existing findings by (b) focusing on the affirmative narratives on sexual inactivity in later life (c) among older women with a more traditional socio-cultural background, (d) with the aim of contributing to better understanding of the phenomenon in question and illuminating the area in between the dichotomy of ‘asexual old age’ and the ‘sexy oldie’ stereotypes.

This study analysis is centred exclusively on female participants’ experiences and narratives. As gendered differences on the meaning of sex or preferable types of sexual encounters have been observed, and the traditional sexual scripts give various instructions to women and men on how to be sexual, what to pursue and what sexual behaviour is (im)proper (Hinchliff and Gott, Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008; Masters et al., Reference Masters, Casey, Wells and Morrison2013; Gore-Gorszewska, Reference Gore-Gorszewska2020), it is reasonable to expect that the motives for sexual inactivity in later life may be different for ageing women and men. Relevant male narratives about not being sexual in older age are explored in a separate study.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

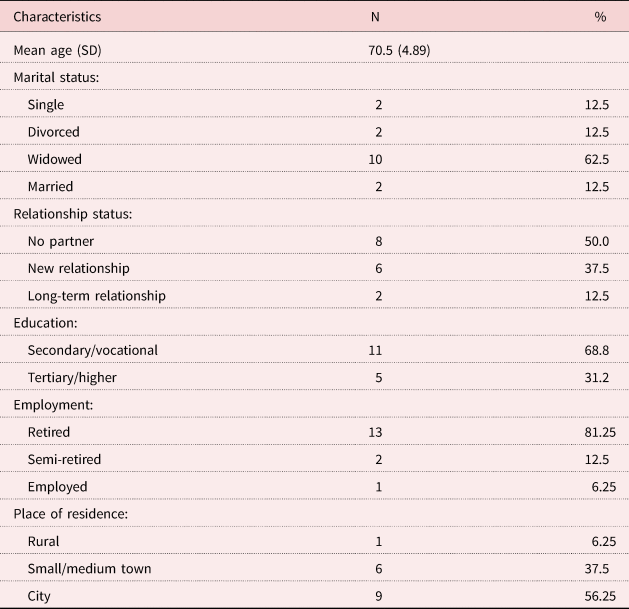

This article is based on the findings from 16 semi-structured interviews with older Polish women aged 65–82 (mean = 70.5, standard deviation = 4.89). Coming from an ethnically homogenous and highly religious Roman Catholic country (Halman, Reference Halman2001; GUS, 2015), all but one declared as a religious person; all 16 women self-identified as heterosexual. Despite this homogeneity, the sample was relatively diverse in terms of relationship status, educational background and socio-economic status of the participants (see Table 1). While participants’ current relationship status varied between being single or partnered (in new or long-term relationships), the majority of women (N = 14) had had a period of sexual inactivity in later life, which they referred to during the interviews.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample

Notes: N = 16.

Study participants were recruited through posters distributed at health centres, pharmacies, University of the Third Age (U3A) venues and in a retirement home, in two cities in southern Poland. The posters gave an invitation to contact the interviewer, and the study was presented as focused on older adults’ experiences and feelings about their sexual and relational life. Individuals who contacted the interviewer were provided with concise information about the project and study procedures, and asked their age (65 or over, no upper limit was set). It was emphasised that current sexual activity was not a prerequisite for study participation. Candidates were also given assurances about anonymity and confidentiality measures, as well as informed of their right to discontinue the interview at any time. None of the participants who accepted the invitation cancelled their appointment, but several interviews needed to be postponed for several days or, in two cases, even weeks.

Data collection

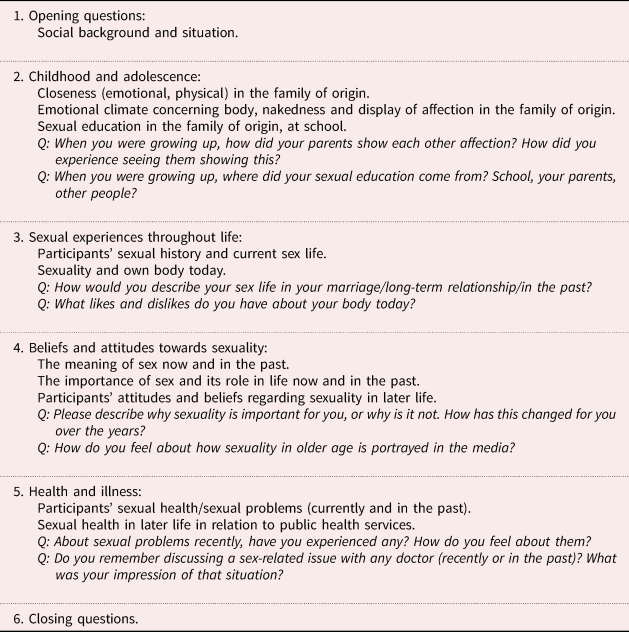

Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted by the author. Being part of a larger study exploring the sexuality of older Polish individuals, the interview guide was broad and addressed a number of topicsFootnote 1 (see Table 2). The conversational style of the interviews allowed the participants to introduce their own topics of interest and enabled the author to address issues unique to an individual biography. The interviews were conducted in the participants’ choice of venue (usually their house or the author's office). All interviews lasted between two and three hours and were audio recorded after obtaining the participant's informed consent.

Table 2. Interview guide: topics and exemplary questions

At the beginning of each interview, the author introduced herself and explained the study goals in order to establish the credibility and trust essential for discussing a sensitive topic. In response to considerable interest about handling qualitative data, participants were assured that their names would be replaced by pseudonyms and that other identifying characteristics would be removed from transcripts. To facilitate rapport, the interviews began with questions regarding the participant's demographic background and relationship history, before asking more sensitive questions about their sex life. After the interview, the participants completed a brief self-administered demographic form. They were compensated for their time with PLN 100 (approximately €25/ US $30). All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University.

None of the interviewees expressed any discomfort or distress after the interview. On the contrary, many reflected on the conversation as meaningful, gratifying or even enlightening, although some admitted being moderately nervous at the beginning, mainly due to uncertainty about how the interview would progress (sensitivity of the topic, their first experience of participating in a qualitative scientific study). Some acknowledged that this was the rist time they had narrated their sexual histories and referred to the interview as their ‘confession’. According to participants, the interviewer's comparatively young age (30+) did not inhibit disclosure. When the age difference between parties in an interview is notable, and the experiences discussed during the interview are impossible to share, it is recommended that young researchers explicitly position themselves as respectful outsiders and treat respondents as experts (Thorpe et al., Reference Thorpe, Hawkes, Dune, Fileborn, Pitts and Minichiello2018). This approach was exercised in the current study and, indeed, the interviewees acknowledged that the regardful yet friendly atmosphere, together with the researcher's gender (female), greatly facilitated the conversation and enabled them to be more open. The interviewer's clinical experience (psychotherapist, sexologist) was important to accommodate possible queries and emotional reactions during the interviews.

All interviews were transcribed by a professional service, following the exclusion of all identifying information. Eight randomly selected transcripts were reviewed by the author against the original recordings for quality assurance purposes.

Data analysis

The main question guiding the current study was: ‘What are the reasons for sexual inactivity in later life among older women?’ A thematic analysis method (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013; Willig, Reference Willig2013) was chosen, with an inductive approach. For exploratory studies, thematic analysis is of particular value, because it allows for minimal a priori assumptions (no theoretically informed coding frame) and enables the ‘discovery’ of (different) meanings directly from the data. The study was informed by a constructivist epistemological approach, which sees knowledge as contextually situated and produced between – in this case – the interviewer and the interviewee (Denzin and Lincoln, Reference Denzin, Lincoln, Denzin and Lincoln2011), with a focus on participants’ subjective ways of constructing meanings rather than seeking to reveal underlying truths (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006).

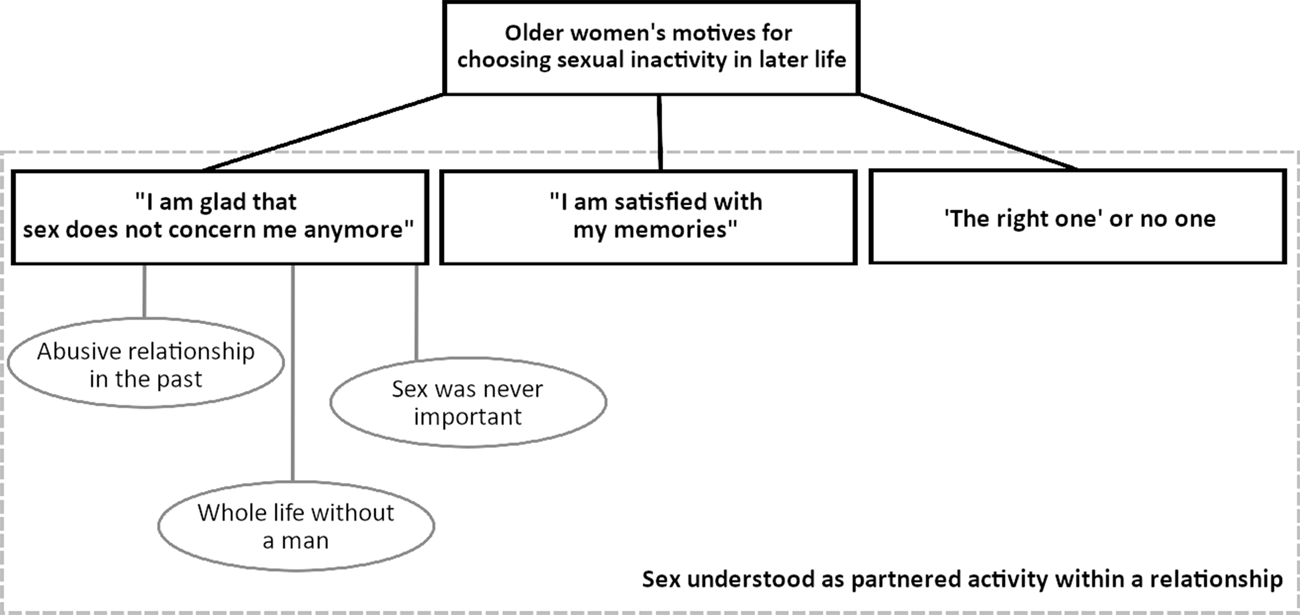

The analysis followed six reflexive steps required to ensure the quality of the thematic analysis and the trustworthiness of findings (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013). The author familiarised herself with the data through multiple readings of all the transcripts and noted the initial ideas. The coding process then followed. The coding labels encompassed the notions that emerged from the participants’ accounts, most often in the form of in vivo codes (inductive approach). A sub-sample of the transcripts (N = 5) was open-coded by an independent researcher (a psychologist familiar with qualitative methodology) to ensure the coding validity. Differences between the two coding outcomes were resolved through discussion. The codes and corresponding statements were collated and combined into a number of themes, then reviewed for internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The reviewed themes were then applied again to the transcripts. In the process, which was characterised by going back and forth between coding and reviewing the themes, several themes were modified and finally organised into a thematic map (Figure 1). Analytical rigour was maintained throughout the recurrent discussions between the author and independent researcher in order to meet the methodological standards for qualitative research (Sinković and Towler, Reference Sinković and Towler2019), and step-by-step notes were made, documenting the research process and substantive findings. MAXQDA software was used for all data analysis.

Figure 1. Final thematic map presenting the motives for choosing sexual inactivity as identified in the narratives of older women.

To ensure the richness of the data and to allow the reader to evaluate the elements of the analysis and its interpretative conclusions, direct quotations from interviews are provided. The quotations were translated from Polish by the author and verified by a professional translator.

Results and discussion

The participants’ accounts of their sexual inactivity were organised into the following three main themes: (a) ‘I am glad that sex does not concern me anymore’, (b) ‘I am satisfied with my memories’, and (c) ‘The right one or no one'. During the analysis, it became clear that the narratives were firmly anchored to past relationship experiences and individual evaluation of current lifestyle. Women's life trajectories analysed in this study were complex, with sets of interwoven motives for not wanting sex in later life. However, it was usually possible to identify a dominant theme in each life story.

All three themes were framed within the participants’ universal understanding of sex as a partnered activity within a relationship; although their definitions of sex were rather broad, beyond penetrative intercourse only. When prompted about masturbation, most women reported not practising it earlier in life and not considering it within their current sexual repertoire:

Well … not really. I have never done this … Honestly, I wouldn't even know where to start. No, somehow it doesn't seem right. (Zuzanna, 66, married)

Similarly, casual sex did not seem to be an option that the interviewees would consider. The majority equated engaging in sexual activity with being in a committed (formal or informal) relationship and usually also living with a sexual partner:

I wouldn't be able to have sex with someone to whom I don't feel anything, about whom I don't know anything, with whom I am not in a relationship, and so on. Unacceptable. (Dorota, 65)

Whenever a question about sex was asked, the participants responded with the implicit assumption that it requires a romantic heterosexual relationship.

‘I am glad that sex does not concern me anymore’

One distinct motive for older women to welcome sexual inactivity in later life was when they considered themselves happier on their own than with a partner. This group of participants greatly appreciated their current lifestyle – single, active and independent. Within this theme, three specific sub-themes (life trajectories) were identified.

Abusive relationship in the past

Negative sexual and relational experiences in the past marked the first trajectory. Given that many women had no sexual experiences outside marriage, sex was automatically linked to a husband figure and to the emotional climate of marital life, which in several cases were notably negative. Julia, a 70-year-old widow explained: ‘My life was … I went through hell. I lived with a psychopath … He was merciless, immoral, [he had] no consciousness, no feelings’. Her husband abused her physically and emotionally, with long-lasting effects on her self-esteem and psychological wellbeing. Regarding their sex life, Julia recalled: ‘It was impossible to satisfy his needs. I felt like an object, I knew there is only one thing he cares about [ejaculation, own pleasure]. Would you like to be an object?’ (Julia, 70) It took Julia many years to recover from these memories and find some joy in life. A similar narrative came from Helena, a widow who had struggled with a heavy-drinking husband who had many lovers. She found him repulsive and despised having sex with him, which resulted in her avoiding sexual contact, unless for procreation:

When I got married, I wanted children. Apart from that, no [sex]. I never felt [sexual] pleasure. I had more joy in giving birth to children than in making them. How can one have the pleasure of getting close to such a dirty, terrible person [husband]. No talking, no feelings, nothing. I knew he has others [women], that he didn't want me … How could sex be pleasurable? How could I wish to undress in front of him, to look at him naked, when he was disgusting? (Helena, 76)

Both women shared traumatic sexual experiences during their long-term marriages and very clearly stated that widowhood was liberating for them. They declared that they appreciated currently living on their own, socialising and engaging in various activities. Having only negative and painful memories of sex and their sexual partners, they expressed no desire to engage in sexual activity in later life.

It appears that in certain life scenarios the cessation of sexual activity might be optimal. Lagana and Maciel (Reference Lagana and Maciel2010), who investigated sexual desire among older Mexican-American women, observed that the respondents with a history of intimate partner abuse reported neither sexual desire nor sexual fantasies in later life. Similarly, Carvalheira et al. (Reference Carvalheira, Graham, Štulhofer and Træen2020) recently reported that older partnered women who were dissatisfied with their relationship were more likely to actively avoid sex. It can be hypothesised that such life trajectories may be more prevalent among older women with conservative socio-cultural background, whose sexuality developed under the dominance of patriarchal norms, gender inequality, double standards and masculinity-oriented sexual societal scripts (Galland and Lemel, Reference Galland and Lemel2008; Petersen and Hyde, Reference Petersen and Hyde2011; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Stelle and Bell2017). This may also explain why the interviewees’ accounts of liberation from unsatisfying relationships did not encompass enjoying sexual freedom, as observed in other studies (Montemurro, Reference Montemurro2014b; Rowntree, Reference Rowntree2014). Given that painful sexual and/or relational experiences may be common to women across cultures, this factor should be acknowledged as a possibility in cases of older women embracing the cessation of sexual activity in later life.

Whole life without a man

Living for a long time without a sexual partner was another life trajectory resulting in female participants claiming to be not interested in sex and happy on their own. ‘A whole life without a man, I couldn't even imagine to be with a man now’, stated Elżbieta, a 77-year-old, who has never been in a long-term relationship. Her last sexual experiences (at the age of 40) were with a partner who left after discovering she was pregnant. Similarly to Elżbieta, several other participants referred to the common expression ‘use it or lose it’, indicating that they had already lost it – their sexual desire – yet without an overwhelming feeling of a loss: ‘There was no time for men in my life, and I do not particularly regret it’, said 82-year-old Bożena. She divorced after five years of marriage, when she realised that her husband had schizophrenia but was unwilling to treat it. Like many single mothers, she had to be self-sufficient. She focused on her child and earning enough to support the two of them, leaving her sex life aside:

The first 10–15 years of bringing up a daughter and working to support us both, of course I did not have the energy or time to think about men or sex. And over the next 10–15 years, this has become established. I was promoted at work, so there was more money, but also more responsibilities … There were some casual relations, but more of a social kind. I admit I have had several men, but I can't say that the world has turned upside down (laugh). It [sex] was nothing special. This only confirmed that I was not interested in this aspect of life. And it stayed like this ever since. (Bożena, 82, divorcee, single)

Her narrative illustrates how a set of life challenges, reinforced by the internalised societal norm that pursuing personal happiness (including sexual fulfilment) should not be a priority for a mother, has set Bożena on a certain path. Now, after reflecting on her lifecourse, she noted that should she have at some point met a man who would ‘turn her world upside down’, perhaps she would currently see things differently and be in a sexual relationship. Since it had not happened, Bożena asked a rhetorical question: ‘If I haven't had [enjoyable] sex for 40 years and I am perfectly fine with it, why should it bother me now?’. This statement captures the overall tone of narratives supporting this theme – viewing sexual activity as expendable. In these cases, it is likely to be the consequence of experiencing unfulfilling sexual encounters, and, over time, disassociating sexual activity from wellbeing and achieving life satisfaction.

In addition to unfavourable life circumstances, which pushed several of the interviewed women – like Bożena – towards prioritising specific duties over sex, there was a notable absence of a hedonistic aspect of sexual expression in their narratives. Whereas experiencing pleasure has been found to be strongly associated with maintaining an active sex life (Kontula and Haavio-Mannila, Reference Kontula and Haavio-Mannila2009), it should be noted that female sexual satisfaction was a neglected or irrelevant aspect of sex within societies with highly conservative views about sexuality (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Wu, Ho and Pearson2011; Mikołajczak and Pietrzak, Reference Mikołajczak, Pietrzak, Safdar and Kosakowska-Berezecka2015). Both women and men in older generations admit to being influenced by the traditional sexual scripts focusing on male sexual gratification and the submissive female role of dutiful wife, whose own desire or pleasure was unimportant or even inappropriate (Montemurro, Reference Montemurro2014a; Gore-Gorszewska, Reference Gore-Gorszewska2020). Thus, prioritising other responsibilities over sex may have robbed some women of the opportunity to learn about and pursue the hedonistic aspect of sexual activity. Taken together, this could explain why some older women – who have not had a chance to enjoy sex earlier in life – report discontinuing sexual activity with no regrets. The societal script of ‘asexual old age’ may be welcomed and comforting for some women who have already closed and forgotten their sexual past lacking positive sexual experiences.

Sex was never important

The third trajectory resulting in older women enjoying their present life without a sexual partner was revealed in the narratives of women for whom sex was never an important aspect of life. Dorota had two significant relationships in her life: first in her thirties, with a partner who eventually left her for another woman, and the second when she was between 45 and 59 years of age. She recalls the second relationship, which ended when her partner died, as satisfying; they were ‘a match as a couple, socially and intellectually’. They engaged in various sexual activities, which Dorota said she enjoyed, especially after menopause when the risk of pregnancy disappeared. Yet she claimed:

It [sex] was never that important for me. Companionship, yes, mutual understanding. I knew he likes sex so we had it, but I could easily have survived without it. It was very optional for me, very … Like icing on a cake. I was always more about the cake; icing was for him (laugh) … Don't get me wrong, I enjoyed it, never sacrificed myself. But I think I enjoyed it mostly because he loved it. (Dorota, 65, single)

Dorota's account reveals interesting contradictions. On one hand, she refers to sex as a non-essential activity she was exercising primarily for her partner, suggesting a script of sex as ‘a marital duty’ or ‘an external experience’, observed among some older women (Kasif and Band-Winterstein, Reference Kasif and Band-Winterstein2017; Gore-Gorszewska, Reference Gore-Gorszewska2020). Yet Dorota claims differently – that she enjoyed being intimate, experienced orgasms and never considered sex as a sacrifice for the sake of a relationship. She seems to be drawing from a script about women gaining pleasure out of sex by giving pleasure to a man, yet she also admits to receiving sexual pleasure during sex herself. Her account creates an intriguing case where sexual activity can be pleasurable and at the same time have a rather low priority in one's life.

When asked about her sex life now and expectations for the future, Dorota stated with stark honesty that she does not want sex anymore. According to her, when she looks at her partnered life from the current perspective:

The sex – physical and the intimacy – was nice, but there were also the downsides of being in a relationship … and this difficult time when he was ill and then he was gone. I was depressed, so sad. Lonely … Eventually I got over it and I'm happy again with my life. (Dorota, 65, single)

Dorota's narrative reveals how being single – and enjoying the lifestyle associated with it – boosted her self-confidence, self-esteem and overall happiness. Despite many fond memories of partnered life, she sees no place for sex in her current life and has no wish to be in a relationship in the future. This and similar narratives suggest that even if sex was part of a woman's earlier life, but was not considered an important aspect of it, there is no reason to expect late adulthood to bring major changes to this attitude.

The first theme, ‘I am glad that sex does not concern me anymore’, opposes the ‘sex as crucial in ageing successfully’ societal script. While there is evidence suggesting the benefits of sexual activity on physical and psychological wellbeing in later life (Woloski-Wruble et al., Reference Woloski-Wruble, Oliel, Leefsma and Hochner-Celnikier2010; Štulhofer et al., Reference Štulhofer, Hinchliff, Jurin, Carvalheira and Træen2018), the current and other studies indicate that it might not always be desirable (Lagana and Maciel, Reference Lagana and Maciel2010; Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015; Carvalheira et al., Reference Carvalheira, Graham, Štulhofer and Træen2020). The emphasis on sexual function as part of successful ageing may put pressure on older adults who do not feel the need to be sexual anymore (Katz and Marshall, Reference Katz and Marshall2003; Syme et al., Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019). Moreover, it overlooks the fact that in some cases sex might not be regarded as a cherished aspect of personal history. The narratives of this study's participants provide a nuanced insight by encompassing the accounts of older women whose current sex(less) expectations were shaped by their – not always joyful – sexual past.

When asked about potential reasons or benefits for later-life sexual activity, the participants commonly referred to maintaining vitality and escaping loneliness. Yet at the same time, they challenged this perception:

Interviewer: Why do you think people get together in later life, like that friend you mentioned?

Helena: Because they do not know what to do with their time, maybe lack of money, maybe they don't want to be alone? Not everyone is OK with being on their own. Me, I can fend for myself, and I am never bored. I have friends, I travel, I'm active, I always have something to do. I am by no means lonely. (Helena, 76)

Helena's and other women's narratives revealed that there are personal histories in which joie de vivre and overall satisfaction flourished after sex ceased to be a part of life. In such narratives, being single is not perceived as worrying but rather as well-deserved freedom and independence. For some women, being active, busy and in good health was possible precisely because of their decision to leave their partnered and sexual life behind. Most of these women proudly declared that they fulfilled their role as a mother and grandmother, and currently pursued other life goals, hobbies and interests (i.e. physical activity, socialising, travelling, engaging in seniors’ activity centres and the education they provide). Investing time and energy in a sexual relationship was perceived as time-consuming and suboptimal in comparison to their current lifestyle:

I have so many things to do, on my own and with friends, and it's so much fun, that sex is at the very, very bottom of my list, honestly (laughter). (Edyta, 72, widow, single)

It cannot be ruled out that the interview context played a role and participants may have positioned themselves as content with their current lifestyle in order to gain the interviewer's approval. However, the overall tone and the details of their life narratives support the assumption that they indeed feel satisfied, despite the lack of a partner and their sexual inactivity.

Similarly to the participants in the Fileborn et al. (Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015: 71) study, many of the women interviewed who remained single ‘privileged their independence and other life goals above the sexual intimacy and satisfaction that could (potentially) be gained through starting a new relationship’. These narratives are in contrast with some other qualitative findings. For example, Ševčíková and Sedláková (Reference Ševčíková and Sedláková2020: 975) observed that some older adults maintained sexual activity ‘to feel and act vigorously, vitally, and youthfully’ or to avoid loneliness. Others expressed concerns that the cessation of sex would make them feel old, unattractive and lonely (Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon, Reference Gewirtz-Meydan and Ayalon2019; Ševčíková and Sedláková, Reference Ševčíková and Sedláková2020). It appears that the discrepancy between perceiving sex as crucial for feeling alive and functional, and seeing sex as redundant or even impairing one's wellbeing, can be explained by focusing on older women's past experiences. It is to be expected that sex will not be a preferred way of improving later-life wellbeing if it was a non-essential, insignificant or undesirable aspect of earlier life.

I am satisfied with my memories

Another distinct motive for embracing sexual inactivity in later life emerged from the interviews with several widowed participants and could be summarised with the phrase: ‘I am satisfied with my memories.’ This theme's underlying narratives were bursting with vivid feelings for the late husband and positive memories of marital life, clearly indicating why it is impossible for those widows to redirect their interest towards a new partner. When answering a question about the possibility of entering a romantic or sexual relationship in the future, Krystyna replied:

(Looking at her husband's photograph on the wall) I don't know if I could cheat on you, darling. No one would be like him … You see, my husband was a perfect man for me; both physically, he was tall, dark haired, very masculine; and as a life partner. (Krystyna, 71, widowed)

It should be noted that Krystyna and several other women with comparable experiences and precious memories of their late husbands were not only referring to the beginning of their marriage, but also to later time-points. Their stories, however, were not idealised; they included reminiscences of ups and downs in the relationships, disagreements and even discoveries of infidelity. Some interviewees admitted that their marital sex life was not always satisfactory for them, but this did not seem to affect their overall evaluation:

The more complete, fulfilling, the marriage was, the less things that would otherwise be sexually interesting are appealing to you. You have nothing to search for since you already had it in your marriage. And I had a perfect marriage. I have to say that I have lived through these years [of marriage] very fruitfully, cheerfully, happily. So now I am not looking for anything, a new partner to live together or to have sex, I do not need anything else. (Teresa, 75, widowed)

Teresa reflected on her marriage as ‘fulfilling’ – sexually, emotionally, relationally – and elaborated on how she felt satisfied, even ‘complete’, with no urge to continue her sex life. Her narrative demonstrated the power of marital memories. Remembered favourably, their past sex life is reflected in current satisfaction, despite the absence of physical sex. Wiki, a widow who explicitly stated how much she used to enjoy sex in both of her marriages, explained:

Interviewer: Do you currently have sexual needs, to be with a man?

Wiki: Not really. Jesus, what I've had, I've already used up my potential. I had crazy times in bed with both of them [husbands]. But now I have the feeling that I've had enough of it. When I was younger, married, I had energy and strength to enjoy sex. It is like with travelling: you explore the world and at some point you have enough, you don't want to travel any more, just settle down. So now I've settled down sexually. I like my memories, but that's it, no more. Does it make sense? (Wiki, 69, widowed, single)

Wiki's metaphor is illuminating; despite positive past sexual experiences she considers the sexual chapter of her life closed and has no desire for it to continue. A certain change in the perception of sex can also be seen in her statement. From this participant's later-life perspective, sexual activity – important earlier in life – gives way to satisfying sexual memories. Wiki's whole narrative, including body language throughout the interview, supported her claim that she feels happy and content about what appeared to be a well-deserved sexual retirement.

In contrast to Wiki, two widows admitted occasional sexual desire. However, both firmly stated that experiencing these feelings or needs were always triggered by memories of sexual intimacy with their late husbands and were adamant that they were not wishing for sex with someone else:

I feel the same [sexual] need [as before]. What do you think, that when I see a romantic film, it does not bring back memories? That it doesn't move me? It certainly does! But I wouldn't go with another man. I couldn't … If he touched me somehow more intimately, if he tried to approach me, if he gave me the look, I would have slapped him. I just couldn't imagine myself being intimate with another man. (Krystyna, 71, widowed)

Missing sexual intimacy experienced by these women does not motivate them to seek a new relationship. The fabric of their sexual desire is made of erotic memories about a particular partner, making it seemingly impossible to imagine a new lover and unwilling to start new chapter of their sex life.

These deeply emotional narratives challenge some of the well-established societal sexual scripts. According to the stereotype of ‘asexual old age’, still prominent in more conservative societies (Sinković and Towler, Reference Sinković and Towler2019), women are not expected – or even supposed – to be sexual in later life (Hinchliff and Gott, Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008; Thorpe, Reference Thorpe2019). In line with this, older women who ceased being sexual at some point are naturally assumed to conform to this script, particularly when coming from a sociocultural background where the primary purpose of female sex was reproduction or fulfilling a partner's sexual needs (DeLamater, Reference DeLamater2012). Narratives of widows in this study offer an alternative to this assumption. Despite not seeking out new partners, they consider themselves sexual beings and actively reminisce about their intimate past.

In contrast to what Kasif and Band-Winterstein (Reference Kasif and Band-Winterstein2017) reported, none of these widows seemed to be abstaining from sexual activity due to social constructions. While it may be attributed to the interview context and participants’ reluctance to discuss such influences, even when gently prompted the widows made no reference to factors like inhibitions originating from family expectations (to remain sexless when widowed) or obligations to remain loyal to the late husband's memory. Instead, strong emotional attachment and still vivid feelings of love and commitment to the late husband were woven into their narratives. Although two widows’ accounts resonated with what Radosh and Simkin (Reference Radosh and Simkin2016) described as ‘sexual bereavement’ – mourning the loss of sexual intimacy – there was no indication that a normative factor (e.g. societal scripts, feeling of grief or guilt) prevented them from forming a new sexual partnership. Even though the script of ‘faithfulness to one, lifelong relationship’ may be common among older women from traditional backgrounds, it might be argued that a strong and positive emotional bond with a late partner has the power to change the meaning of sexual inactivity in one's later life.

To summarise the second theme, a number of women in this study who were sexually inactive were nevertheless satisfied with their sex life due to positive past sexual experiences. Comparable findings are found in a recent study by Syme et al. (Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019) who observed that for some mid-life and older women, who faced challenges in their sex life, sexual memories or fantasies can provide a refuge and even generate sexual satisfaction. What the current study adds is that some older women may feel sexually satisfied even after definite cessation of their sex life, provided that they cherish their sexual history. These findings are supportive of the wellbeing paradox: the notion that older adults’ subjective wellbeing does not necessarily reflect an objective decline in many life domains (Hansen and Slagsvold, Reference Hansen and Slagsvold2012). In contrast, a decline in sexual activity (including sexual abstinence) can be accompanied by a feeling of genuine satisfaction that is embedded in a broader perspective on satisfactory intimate life and reinforced by positive erotic memories. Indeed, it appears that ‘sexual wellness is attainable at any level of functioning’, including sexual inactivity (Syme et al., Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019: 839).

‘The right one’ or no one

The interviewed women's narratives indicated that the most common reason for older women's sexual inactivity – a lack of partner (Træen et al., Reference Træen, Hald, Graham, Enzlin, Janssen, Kvalem, Carvalheira and Štulhofer2017) – might be more nuanced than the straightforward statement: ‘I don't have a partner, thus I don't have sex.’ As can be observed in the accounts that follow, there is a crucial difference between lacking a partner and lacking a desirable partner. While quantitative studies do not make this distinction, some qualitative findings suggest that this may be salient for older women (Rowntree, Reference Rowntree2014; Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015). It has been observed, for example, that ‘a perceived lack of “decent” older men coupled with unwillingness to compromise on relationship standards’ led some older Australian women to remain single despite declaring an interest in forming a new relationship with ‘the right one’ (Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015: 74). The current study corroborates these findings by demonstrating the circumstances in which older women may prefer the cessation of sexual activity to having sex with a partner who does not meet their expectations.

In contrast to the accounts representing the previous theme, several interviewees mentioned that they would be interested in a new relationship. However, they emphasised how sex would only be possible with someone who meets numerous stringent criteria – sensible economic status (pension, own flat), reasonable health (‘I won't be a nurse’), gentleness and having interests similar to hers (‘so we understand each other, and we can talk, spend time together, have fun’). None of the women were willing to engage with ‘just anyone’ to be sexual again, although they were acutely aware of the gender disproportion in older age cohorts and the corresponding challenge of finding the ideal partner. Eliza, a 65-year-old divorcee, currently partnered but sexually inactive, clarified that sexual needs have not disappeared from her life. On the contrary, they are still present but not as overwhelmingly as they were when she was younger. Eliza claimed that being more reasonable and considerate, even pragmatic, at this stage in her life, was the reason why she did not want to engage fully with her current partner:

Above all, equal material status. A relationship cannot be based on what only a woman has. Equality, then we are partners … I'm not that desperate for sex and intimacy to fall for a man that I would have to support for the rest of my life. (Eliza, 65)

Many participants shared similar thoughts on how, in later life, they began to recognise a sense of equality among partners as vital for intimacy, and therefore how they would only consider men who are willing to respect their independence and equal status in a relationship as ‘the right one’.

Meeting the right person has, in some cases, the power to reconstruct individual sexual scripts, as was the case of Maria, a 65-year-old widow, who recently found a new sexual partner. She recalled being physically and emotionally abused in her marriage, which led her to two decades of sexual inactivity:

My marriage was not made of roses, more like thorns … He [husband] was never gentle, in bed or else … I used to run away from home when he was drunk. (Maria, 65)

This affected her attitude towards sex since she had no sexual experiences outside of marriage. After leaving her husband she found peace as a single mother and admitted not wanting sex ever again in her life. She claimed to have no sexual desire nor any intention to enter a relationship. However, after her current partner – whom she initially considered ‘just a friendly person’ – proved to be reliable, gentle and caring, she considered having sex again. Meeting ‘the right man’ was precisely what changed her attitude and sparked her interest in sexual intimacy. But, as Maria claims, had she not met him she would surely follow the ‘asexual old age’ script.

Waiting for the right partner, while being content with sexual inactivity, seemed to be the option facilitated by being ‘blessed with the lack of urge’ – as Sylwia (70, divorcee) put it. She resumed engaging in short-term relationships following a period of sexual celibacy. Because of her reportedly low sexual desire, Sylwia confided that she is able to enjoy sex only when she feels like it and only with a carefully chosen partner:

First of all, I respect myself and I will not go fast, no ‘sex on a first date’. Why would I, there is no desperate need. I want to get to know a man a little bit, talk to him. If there is a spark, if talking with him is fun, if there is something to talk about, because he is intelligent, but he also seems sensitive, only then I can go on with this relationship. (Sylwia, 70, divorcee)

To be sexual, Sylwia prefers to form a relationship, and must know a man well to enable her to decide whether he is intellectually and emotionally engaging enough to become her partner. She expects a longer and deliberate commitment, which allows the partner to learn her preferences, and to also meet her standards at the later stages of a relationship:

I enjoy sex nowadays, because I know what I want. I don't need a lot [of sex] but I have found out that it can be pleasurable, and now I know what I like and how I like it. So, I'll show him or tell him, and either the guy follows, or he can get lost.

In her opinion, low sexual desire puts her (and some other older women) in a favourable position, because they can freely decide whether and when to have sex. In addition, it may be easier for them to see whether a potential partner is ‘the right one’. A similar perspective was voiced by Katarzyna, who straightforwardly explained why sex is optional in her life:

I am not desperate [for sex]. On the contrary, there will be sex only when I want it and how I want it, or no sex at all. (Katarzyna, 70, widowed, partnered)

This quote illustrates how lower sexual desire coupled with recognising their own sexual preferences may allow older women to be more prudent and demanding regarding potential sexual partners.

The third theme, represented by accounts of preferring sexual celibacy when faced with the lack of desirable partners, can be interpreted as a reflection of older women's sexual agency and their transgression of traditional sexual scripts. Firstly, they use the ‘asexual old age’ stereotype to their benefit – it liberates them from the traditional expectation of sex as ‘a wife's duty’ (‘I don't have to do it anymore; I simply can if I want to’). Secondly, they consider their ‘lower sexual desire’ as something positive – a release from the urge to pursue sexual fulfilment. This perspective may be supported by accounts of older women who admit fulfilling sexual needs can sometimes be challenging, frustrating or distressing (Hinchliff and Gott, Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008; Kasif and Band-Winterstein, Reference Kasif and Band-Winterstein2017; Ayalon et al., Reference Ayalon, Gewirtz-Meydan and Levkovich2019). Finally, the fact that some older women would not unconditionally accept sex, but name a set of requirements for a potential partner and relationship, indicates development of a sense of sexual agency that many of them were lacking earlier in life (Mikołajczak and Pietrzak, Reference Mikołajczak, Pietrzak, Safdar and Kosakowska-Berezecka2015; Gore-Gorszewska, Reference Gore-Gorszewska2020). Their narratives resonate with what Montemurro (Reference Montemurro2014a) described as women's ‘sexual subjectivity’ or the process of developing sexual self-acceptance that enables making autonomous decisions about one's sexuality and acting confidently. It has been reported that older women usually exercise their sexual agency through remaining sexually active despite their advancing age (Hinchliff and Gott, Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008; DeLamater et al., Reference DeLamater, Koepsel and Johnson2019). However, as observed in the current study, some women seem to demonstrate that an increased sexual agency may also result in the decision to abstain from sex. This increased confidence in exercising a choice about whether to be sexual echoes the concept of sexually ‘liberating’ ageing described by Gott and Hinchliff (Reference Gott and Hinchliff2003) and Rowntree (Reference Rowntree2014).

Conclusions

Based on the assumption that sexual inactivity might be a welcomed life trajectory, this study aimed to explore and understand the motives for embracing sexual inactivity among older women. The results indicate that when not restricted by a set of options (such as lacking a partner or experiencing health problems), older women provide a variety of narratives to explain why they do not engage in sexual activity. For some, sex seems to have been given up for good, with no regrets or feeling of a loss; for others, it may be a temporary decision, its duration dependent on meeting the right partner. Sexual (in)activity seems strongly connected to their sexual past and memories of their relationships, which resonates with the conclusion of Hinchliff et al. (Reference Hinchliff, Gott and Ingleton2010) that personal factors seem to be central in shaping older women's sexual experiences and expectations. In contrast to what has been reported in the literature, physiological (health-related) factors may play a less-pronounced role in older women's cessation of their sex life (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson, O'Muircheartaigh and Waite2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nazroo, O'Connor, Blake and Pendleton2016). Although this study addressed a specific topic and only explored female accounts, it offers several potentially interesting findings and implications for consideration in further research and practice.

Firstly, the life trajectories of the interviewed women suggest that promoting sexual activity as an element of successful ageing should be applied with caution. In cases when sex has no positive connotations for an individual, cessation of their sex life may be favourable, even liberating. As shown in recent research, sex is not always a necessary element in successful ageing (Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015; Syme et al., Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019; Thorpe, Reference Thorpe2019). Life trajectories filled with negative sexual experiences can occur regardless of an individual's sociocultural context and should be considered in both research on sexuality in late adulthood and in educational and therapeutic interventions aimed at older adults.

Secondly, the results of this study illustrate that a sense of sexual agency may empower older women in their decision to discontinue sex. The development of sexual agency is usually associated with enriching one's personal sex life (e.g. through increased self-awareness, greater knowledge about sex, competence or courage to negotiate with a partner) (Hinchliff et al., Reference Hinchliff, Gott and Ingleton2010; DeLamater et al., Reference DeLamater, Koepsel and Johnson2019). However, it appears that for some women the development of greater sexual self-awareness, decisiveness and firmness can result in a decision to withdraw from a sexual life, as has been observed in this study. It may be speculated that such an attitude would be more prevalent in women whose sexual past was dominated by sexual scripts oriented towards male pleasure and female submissiveness, and who lack positive sexual experiences. Interestingly, this framing would place older women who have made the choice to give up sexual activity in a position of transgressing sexual scripts, as opposed to those women who are still sexually active because of a marital duty or to satisfy a partner's needs. The call for including the sense of sexual agency in conceptualisations of female sexual expression (Montemurro, Reference Montemurro2014a) seems essential, but it is important to also acknowledge the possibility that some older women may be happier not being sexual.

Thirdly, it seems that both positive and negative sexual and relational experiences in the past may result in older women gladly giving up sexual activity. This is more obvious in the case of life trajectories filled with negative and/or painful sexual connotations. Less prominent in the literature is the voice of women who embrace the end of their sex lives precisely because of their positive and fulfilling sexual and relationship experiences. The current study indicates that widows who do not wish to continue sexual activity do not necessarily follow the traditional script of ‘marital loyalty’ or grief-imposed abstinence. On the contrary, they share the discourse of past sexual fulfilment. The accounts presented in the current study seem to correspond with the postulated possibility of attaining sexual satisfaction while remaining sexually inactive (Syme et al., Reference Syme, Cohn, Stoffregen, Kaempfe and Schippers2019). Indeed, it does appear that at least some older women might be satisfied with their sexuality, consisting of memories rather than current activity. This form of experiencing one's sexuality in later life should be considered as equally valid in further research and in clinical practice.

Finally, despite the limited sample size (which is not uncommon among qualitative studies; Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015; Kasif and Band-Winterstein, Reference Kasif and Band-Winterstein2017; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Stelle and Bell2017), the interviewees demonstrated a diversity of sex(less) expectations and reasons for opting for sexual inactivity. The study corroborates previous findings that questioned the validity of perspectives that treat older women as a homogeneous group and/or their sexuality as a uniform phenomenon (Hinchliff and Gott, Reference Hinchliff and Gott2008; Rowntree, Reference Rowntree2014; Fileborn et al., Reference Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello and Pitts2015). While some participants considered the sexual chapter in their life closed, their accounts did not adhere to the narrative of societal constraints or expectations prescribed by the traditional sexual script. It was personal motivations and individual lifecourse events, rather than societal norms, that appeared to guide these women towards ceasing sexual activity.

Although the main strength of this study is that it provides novel insights on affirmative narratives on sexual inactivity among older women, several limitations should also be considered. The recruitment procedure (participant self-selection) has likely resulted in over-representation of individuals who are more comfortable with discussing sexual issues. Although some participants admitted having difficulties talking about their sex life, the voices of less-forthcoming older adults might still be underrepresented. Also, the sample was exclusively heterosexual despite the fact that sexual orientation was not part of the inclusion criteria. This is most likely the consequence of the heteronormative socio-cultural context of older Polish generations; thus, it remains unknown if the experiences of non-heterosexual older women are different. Nevertheless, the sample was diverse regarding age range, relational status and marital histories, suggesting the views presented here are not limited to a specific demographic and may be potentially transferable to other contexts. Finally, the interview context and the interviewer could have potentially influenced participants’ accounts. However, the fact that women in this study openly shared their – also painful – experiences and on occasion referred to the interview as their ‘confession’ can be viewed as a sign of frankness. Participants also emphasised their openness in the research context (‘I'm telling you how it is so you can understand’), suggesting the beneficial effect of the interviewer's respectful outsider status.

Acknowledgements

Special acknowledgement is owed to all the interviewees for their time and contribution, which made this study possible. The author would also like to thank Professor Aleksandar Štulhofer for his encouragement and invaluable feedback, anonymous reviewers for their comments on the earlier draft of this paper, as well as Marcin Górka for his support during the development of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow (grant number DSC/005666) and by the International Visegrad Fund (scholarship number 52110377).

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University, KE/10/042019) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All individual participants included in the study gave their informed consent to conduct and record the interviews, and anonymity and confidentiality was ensured throughout the study.