Introduction

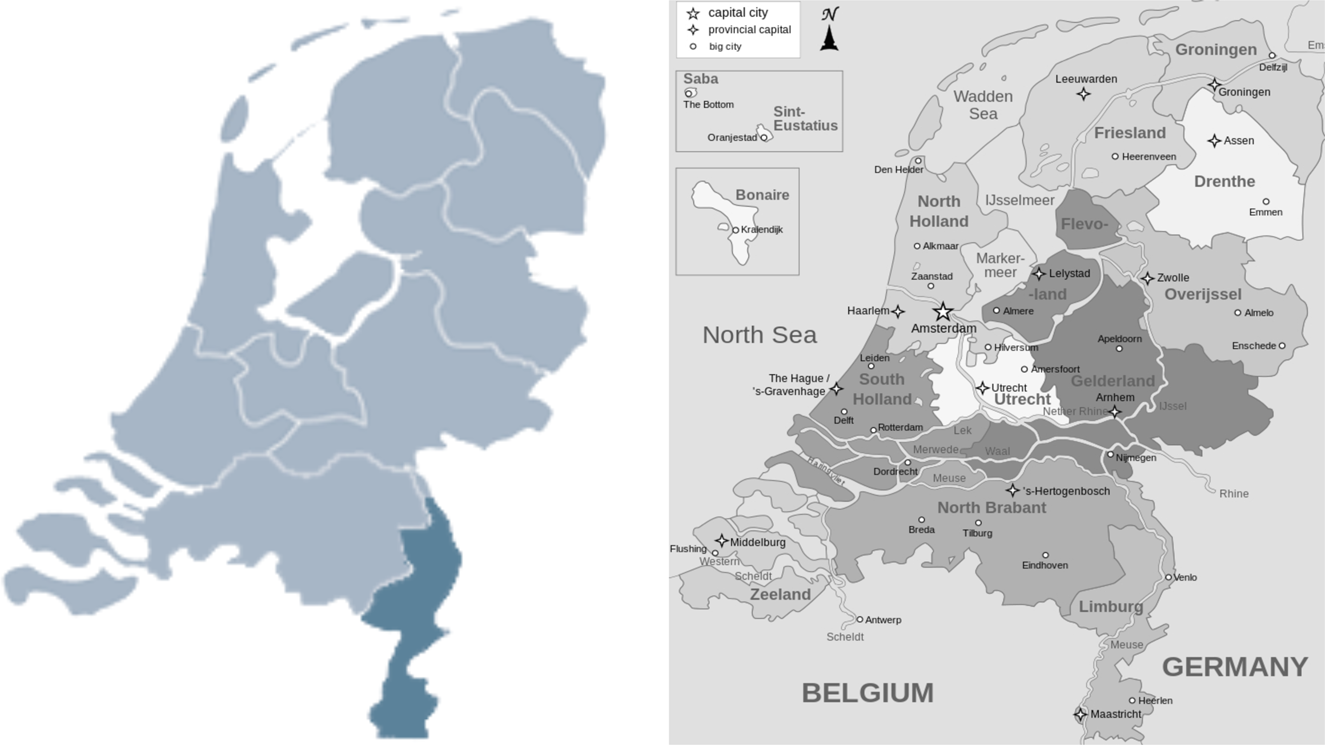

The chief aim of this article is to lay out the societal, political, and educational power dynamics underlying the interruption of production, acquisition, and development of dialect by toddlers in The Netherlands attending the so-called peuterspeelzaal ‘playgroup’ or kinderdagverblijf ‘daycare centre’ (henceforth preschool), although these toddlers acquire Limburgish as a first language. The area of investigation is the province of Limburg, which is located in the southeast of The Netherlands, bordering on Germany to the west and Belgium to the east, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The location of the province of Limburg in the Netherlands.Footnote 1

Limburg is known for its lively use of dialect in public and private spheres (Cornips Reference Cornips, Hinskens and Taeldeman2013). Its dialects were awarded minor recognition under the umbrella term Limburgs ‘Limburgish’ by The Netherlands in 1997, a signatory to the 1992 European Charter for Regional Languages or Languages of Minorities. In addition to Limburgs, dialect or plat are the most common terms used by speakers in Limburg. Minor recognition entails that the Dutch state formally recognizes the status of Limburgish as a separate regional language in The Netherlands (Camps Reference Camps2018) but provides no financial support.Footnote 2 There is no structured policy to ‘protect’ Limburgish but regional and local authorities provide moral support. The use of Limburgish is considered crucial in the construction of local and social identities (Cornips, de Rooij, & Stengs Reference Cornips, de Rooij and Stengs2017) and is flourishing on social media (Jongbloed-Faber, de Loo, & Cornips Reference Jongbloed-Faber, de Loo and Cornips2017). According to a survey commissioned by the provincial newspaper De Limburger in 2016, 66% of the 712 respondents stated that they very strongly agreed, and 30% agreed with the statement that speaking a dialect is characteristic of Limburgian culture/identity (total agreement 96%). Teaching Limburgish as a regular school subject is nonexistent at preschool (Council of Europe/Conseil de l'Europe 2016:8) and primary school level. The Netherlands is a heavily standardized nation-state, hence Dutch is unquestionably the dominant language in Limburg: everyone actively or passively knows Dutch but not Limburgish. Limburgish-dominant children are always brought up with Dutch as well, and Dutch is a codified and standardized spoken and written language whereas Limburgish is only a spoken one. Dutch is the national language linked to economic, political, cultural, educational, and societal power and is seen as the language of upward mobility through higher education and career success (this also holds for English).

The central question in this article is why toddlers growing up with Limburgish as a first language—in addition to Dutch—may stop speaking Limburgish at home when entering preschool although Limburgish might be spoken by teachers and peers there. The question is addressed by taking into account many aspects of what Silverstein (Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985) calls the total linguistic fact: (language) ideology, (child acquisition of) linguistic form, and actual language practices of toddlers and teachers in preschool that mutually shape and inform each other (Woolard Reference Woolard2008). The perspective of the total linguistic fact allows for a more holistic view on how wider societal ideas and beliefs inform teachers’ use of Limburgish and Dutch in preschool and how (in)formal language policy in wider Limburgian society and language practices at preschool have an impact on the toddler's language use at home. The perspective of the total linguistic fact explicitly acknowledges the power dynamics between speakers of a regional and a national language, which is essential in order to account for the refusal to continue a first (second) language (De Houwer & Ortega Reference De Houwer, Ortega, Houwer and Ortega2018) by bidialectal children.

The research question is inspired by the many conversations I have had with (grand)parents, and e-mails that I received from them.Footnote 3 E-mails and oral interactions from (grand)parents generally run as follows.

Two of our grandchildren live next to us in place x. We speak dialect of place x and y, the parents speak dialect, the other grandparents speak dialect and the aunts speak dialect as well. And yet the boys of 6 and 4 years old speak only Dutch. They attended preschool two days per week and Dutch was spoken there. Occasionally, a dialect word can be heard, in the speech of one boy very rarely, in the speech of the other boy sometimes but only when this concerns a new word for them. But this will be corrected very quickly if they also learn the Dutch equivalent. (e-mail from a grandparent in Dutch, received 11 January 2016)

In an interview (Morillo Morales & Cornips Reference Morillo Morales and Cornips2020), a parent explicitly mentions (in Dutch) the child's refusal to speak Limburgish as a first language at home since attending preschool.

Our elder child refuses to speak Limburgish since attending preschool, even though we stick to Limburgish at home. We will keep on answering in Limburgish, then it [speaking Dutch/LC] will be resolved after a while.

And a columnist in the role of father of daughter Suus writes in the provincial newspaper De Limburger in Dutch (Peter Leijsten, 2 December 2017).

In our home we have a dialect saboteur as well…. Whatever I say [in Limburgish/LC] or do, Suus always replies in pure standard Dutch.

These writings express the (grand)parents’ concerns that the (grand)child—even called a dialect saboteur—refuses to continue speaking Limburgish even though the child is addressed in Limburgish by (extended) family members in the home sphere. The parent in the interview keeps on addressing her eldest child in Limburgish, which implies she wants to continue raising her eldest and, hence, youngest child(ren) in Limburgish.

The quotes also reveal that people in Netherlandic Limburg perceive and experience dialect and Dutch as two distinct linguistic identities. When I visited a farm in Limburg (26 April 2019), the farmer informed me without my asking that her two children had stopped speaking Limburgish after entering preschool. I noticed she code-switched in multiparty interactions and used so-called intermediate forms, which is very normal in Limburg (Giesbers Reference Giesbers1989; Cornips Reference Cornips, Hinskens and Taeldeman2013): Dutch with me, Limburgish with a third person present, code-switching while addressing both me and the third person, and Limburgish and Dutch to her children (and dairy cows) depending on whom she tried to engage in the conversation. I indeed heard the children speak only Dutch during the afternoon I visited the farmer, although the farmer addressed them in Limburgish.

Preschool is the toddler's first educational and social setting in The Netherlands in which the use of Limburgish as a first language is extended beyond the family. In the second quarter of 2018, there were 11,695 preschools and daycare centres in The Netherlands.Footnote 4 Preschool in The Netherlands is a voluntary Dutch-dominated educational program that prepares children between the ages of two and a half and four for primary school, which begins at age four. Since January 1, 2018 preschools have turned into formal day care centres responsible to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment rather than the Ministry of Education, which is what one would expect. Although preschool is optional in The Netherlands, almost all toddlers attend one. Statistics Netherlands reported that in 2013 80% of children between the ages of two and three attended a playgroup or daycare centre, where they spent an average of about 7.5 hours per week. The use of preschool is income-dependent in The Netherlands: the cost of childcare is split among parents, their employers, and the government. The use of the regional languages Frisian, Limburgish and Low Saxon is allowed in preschools by Dutch law, as stated in article 2.12 Kinderopvang en kwaliteitseisen peuterspeelzalen ‘Law on Child care and quality demands of preschools’.Footnote 5

Next to adult (extended) family members, teachers and peers provide input and exposure to toddlers (Von Suchodoletz, Fäsche, Gunzenhauser, & Hamre Reference Von Suchodoletz, Fäsche, Gunzenhauser and Hamre2014:509); adults in early childhood preschool are very important in the social context of toddlers (Palermo, Mikulski, Fabes, Hanish, Martin, & Stargel Reference Palermo, Mikulski, Fabes, Hanish, Martin and Stargel2014). Since Limburgish is spoken by both teachers and peers, preschool also provides a new heterogenous environment in which both Dutch and/or Limburgish, in addition to other languages, are used.

Most studies report on migrant children in a migration context who stop using their minority language after entering preschool (De Houwer Reference De Houwer, Cabrera and Leyendecker2017). Research showing a toddler's refusal to speak a ‘traditional’ regional language as a first (second) language at home while growing up in a vital bidialectal and heterogenous community is scarce. De Houwer (Reference De Houwer, Cabrera and Leyendecker2017) states that throughout Europe, once children ‘start regularly attending a preschool, their language choice patterns often quickly change, and they start to limit themselves to speaking just the majority language’ (De Houwer Reference De Houwer, Cabrera and Leyendecker2017:239). There is a lack of knowledge on how toddlers, not adults or adolescents, come to perceive the social and educational value of dialect and standard language, which is crucial in both attitude formation and production (Chevrot & Ghimenton Reference Chevrot, Ghimenton, Houwer and Ortega2018). Mueller-Gathercole & Thomas (Reference Mueller-Gathercole and Thomas2009) found that children growing up in a stable community in which there is a dominant language—English—and a minority/regional language—Welsh—may all ultimately become proficient in English as the dominant language, regardless of what is spoken at home. But for Welsh as the nondominant language it is different since abilities in that regional language are directly related to the age of acquisition and length of exposure (Mueller-Gathercole & Thomas Reference Mueller-Gathercole and Thomas2009:234). In contrast to Limburgish, Welsh is often the primary medium of education, or is used alongside English (Mueller Gathercole & Thomas Reference Mueller-Gathercole and Thomas2009:213). Similarly, Paradis & Nicoladis (Reference Paradis and Nicoladis2007:294) discuss the ability of bilingual children at preschools in the English majority/French minority region of Canada to separate their languages. However, how they use their minority language depends ‘on an interaction of their dominance [of the language involved/LC] and their sensitivity to the bilingual speech patterns of the greater community’ (see also Verdon, McLeod, & Winsler Reference Verdon, McLeod and Winsler2014 for Australia).

Research focusing on the refusal to use a regional language by preschool children is important, since there ‘is overwhelming evidence that parental socioemotional well-being is negatively affected when young children do not speak the minority language that parents address them in’ (De Houwer Reference De Houwer, Cabrera and Leyendecker2017:243). Parents may wish to use a minority or regional language like Limburgish to develop the child's historical, cultural, and social identities and maintain intergenerational links with family members and their community (Verdon et al. Reference Verdon, McLeod and Winsler2014:170).Footnote 6 I received an e-mail from a parent that illustrates these wishes and the feelings that go with it, that is, ‘as if she was not my own child’.

In the meantime she became 26 and fortunately she speaks dialect now. But the first four years of her life were different. In that period, she went to daycare centre every morning. We always speak dialect but our little daughter refused to speak it. I received answers from her in Dutch. As if she was not my own child. I started to read to her in dialect hoping she would adopt it. When she attended primary school, the miracle happened. In two weeks’ time she suddenly spoke dialect. You don't want to know how happy we were with it. (e-mail from a parent in Dutch, received 14 November 2017)

The central question in this article is urgent in light of heritage language maintenance and adults linguistically constructing their parental identities and ‘sense of belonging in the home’ (Juan-Garau Reference Juan-Garau2014:428). The toddler as young as two engages with power dynamics in the wider societal and educational context in an agentic way: (s)he translates ‘attitudes into reality’ while the (grand)parents struggle with their ‘own responsiveness’ to what they consider a problematic situation in the home sphere (Schwartz & Yagmur Reference Schwartz and Yagmur2018:216).

Methodology

I collected and analysed various data sets for this article. The first data set concerns an online search by the key terms Limburgish, dialect, and plat among readers’ reactions published in the provincial newspaper De Limburger, which has about 139,000 readers. These reactions make explicit the internalized norms of how, when, and where Limburgish and Dutch should be spoken. Their reactions thus provide a window into ideology, which is an essential part of the total linguistic fact (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985), that is, how beliefs and ideas of speakers in Limburg inform the (de)selection of Limburgish versus Dutch and actual language practices. The second data set consists of 182 answers to a Limburgish version of the Questionnaire for Parents of Bilingual Children (PaBiQ, COST Action IS0804; Tuller Reference Tuller, Armon-Lotem, Jong and Meir2015). For this article only I did a quantitative analysis of the data on parental input in the home sphere, that is, how many children grow up with Limburgish and/or Dutch from birth onwards. This data set provides insight into the extent of intergenerational transmission of Limburgish as a home language. Although survey data constitutes reported behaviour, it is a mediating link to actual practices by parents and children in the home sphere. I also conducted a simple poll on Twitter. Thirdly, Morillo Morales & Cornips (Reference Morillo Morales and Cornips2020) observed interactions in situated contexts between teachers and toddlers, and between peers in three preschools in Limburg, with a focus on language choice between Dutch and Limburgish. For this article I analysed their findings to address the research question. Finally, I received e-mails and phone calls and had numerous conversations with (grand)parents who stated their concerns that their (grand)children do not want to speak Limburgish any longer at home after entering preschool (see the Introduction).

Bidialectal acquisition and language choice between Limburgish and Dutch as social semiosis

To each language choice made in a social and situated context, new social connotations can be attributed time and again. In producing meaning, people lean on experience-based knowledge acquired by linguistic socialization (Ochs & Schieffelin Reference Ochs, Schieffelin, Duranti, Ochs and Schieffelin2012). During the process of linguistic socialization people learn to link specific linguistic elements or varieties to specific (groups of) people, and to specific contexts and places of use. Differences between a national and a regional language or between linguistic forms associated with them are never free of social meaning (Cornips et al. Reference Cornips, de Rooij and Stengs2017). Children attending a playgroup in The Netherlands are between two and a half and four years old, whereas children attending a daycare centre might be younger. Children may differentiate functionally between two linguistic systems by at least two years of age when they are in the one- and early two-word stages of development, regardless of whether these two systems are associated with two typologically very different (Genesee Reference Genesee, Dewaele, Housen and Wei2002) or very close languages (Chevrot & Ghimenton Reference Chevrot, Ghimenton, Houwer and Ortega2018; De Houwer & Ortega Reference De Houwer, Ortega, Houwer and Ortega2018). Children are sensitive to the language used in the input and the social factors that influence these sensitivities (Ghimenton, Chevrot, & Billiez Reference Ghimenton, Chevrot and Billiez2013).

Bidialectal children as young as two and a half in the midst of acquiring or developing grammar reveal heterogenous learning trajectories. The question as to whether a child of that age becomes a proficient speaker of two languages or both a national and a regional language may depend on the age of acquisition of the second language. Children may acquire two languages simultaneously from birth onwards (simultaneous bilinguals or 2L1) or acquire a second language in earlier or later childhood (successive bilinguals or child L2). Simultaneous bilingual children pattern more like monolingual children showing less cross-linguistic influence in acquiring both languages, whereas successive bilingual children pattern more like adult second-language learners, revealing more cross-linguistic influence depending on the phenomenon under examination (Unsworth Reference Unsworth, Nicoladis and Montanari2016). But whether the child will ultimately become a proficient speaker of both a national and a regional language also depends on a set of correlating factors such as language aptitude, the typological properties of both languages (Cornips & Hulk Reference Cornips and Hulk2008), the quantity and quality of input, that is, the richness and complexity of both language(s) provided in the input (Paradis Reference Paradis2011), and overall length and intensity of exposure at home, extended family, school and/or wider community (Unsworth Reference Unsworth, Nicoladis and Montanari2016). Since child acquisition does not take place in a social vacuum (Cornips Reference Cornips, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018), (hierarchical) role relations and linguistic practices among family and community members (Lanza Reference Lanza1997; Smith, Durham, & Richards Reference Smith, Durham and Richards2013), in school between teachers and pupils, and between peers (Karrebæk Reference Karrebæk2013), and wider societal and political power dynamics (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity2000) are crucial. A so-called monolingual child masters the sound system and grammar of their language and acquires a vocabulary of thousands of words by the age of five (Hoff Reference Hoff, Tremblay, Boivin, Peters and Rvachew2009:1), whereas the age of four is regarded as the critical cut-off point whether a bilingual/bidialectal child will attain proficiency in both languages (Unsworth Reference Unsworth, Nicoladis and Montanari2016:609). Consequently, a toddler who stopped speaking a first language between two and a half and four years old also stops acquiring and developing that language. It is a question of whether such a toddler will ultimately become a proficient speaker of that language.

Little is known about how children acquire indexicalities of regional language/dialect and standard language within societal power dynamics in lively bidialectal communities. Bilingual children of preschool age may start to translate words spontaneously and to use the actual names of their languages (De Houwer Reference De Houwer, Cenoz, Gorter and May2015). Ghimenton and colleagues (Reference Ghimenton, Chevrot and Billiez2013) observed the language practices between Francesco when he was between seventeen and thirty months old and his family members who all speak both Italian and the regional language Veneto. It appeared that Francesco was exposed to a predominantly Veneto input in inter-adult interactions but to Italian when addressed by family members. Francesco gradually adjusted his language production to that of his mother between seventeen to thirty months, preferring Italian to Veneto. But, Ghimenton and colleagues (Reference Ghimenton, Chevrot and Billiez2013) also found that extended family members used more Veneto than Italian in multiparty interactions when addressing Francesco and that Francesco's production mirrored these language choices when interacting with them.

Bidialectal children as young as two growing up in a bidialectal community may also begin to acquire a role-play register by acting out a social role that may involve standard-dialect variation (Katerbow Reference Katerbow, Auer, Reina and Kaufmann2013:147). A role-play register reveals a sociopragmatic competence, which shows that the bidialectal children acquire language awareness and metalinguistic competencies (Katerbow Reference Katerbow, Auer, Reina and Kaufmann2013:145). Katerbow (Reference Katerbow, Auer, Reina and Kaufmann2013:150–51) found that bidialectal children between 3;11 and 6;10 years old who acquire both standard German and Moselle-Franconian used German more to indicate a role switch and when acting in the role of customer or seller, while they used Moselle-Franconian more when talking to each other as peers. Fijnault (Reference Fijnault2011:30) found exactly the same when observing her nephew Pim (5:8, pseudonym) while playing with his younger brother Cas (3;0).Footnote 7 Pim uses Limburgish when consulting his younger brother Cas about their play in (1a), and also about how to play in (1b). But he switches to Dutch when acting in the role of the captain of a submarine in (1c).

(1) Pim using Limburgish (with Dutch in italics)

a. Het spjel geit over nul minute beginne.

‘The play will start in zero minutes.’

b. Nee, ozze boot is te klein heur, hie kin veer neet op laope.

‘No, our boat is too small, we are not able to walk here.’

c. Pas op mannen, jullie hebben een missie!

‘Watch out, men, you have a mission to undertake.’

In his role of captain, Pim chooses Dutch and makes himself taller as well; he balances on his toes and speaks in a higher voice, showing himself aware of the indexicalities of the hierarchical relation between Dutch and Limburgish.

From the above it becomes clear that a toddler from two and a half onwards can distinguish Limburgish and Dutch and is sensitive to societal power dynamics, which will be discussed in the next section.

Language ideology concerning Limburgish and Dutch

According to Silverstein, ‘[t]he total linguistic fact, the datum for a science of language, is irreducibly dialectic in nature. It is an unstable mutual interaction of meaningful sign forms, contextualised to situations of interested human use and mediated by the fact of cultural ideology’ (Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985:220). In this perspective, research into language choice and shift as social semiosis has to concern itself with ‘the integration of a theory of ideology with an account of actual social practice’ (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985:219). Woolard (Reference Woolard2016:7) defines language ideologies as ‘socially, politically, and morally loaded cultural assumptions about the way that language works in social life and about the role of particular forms in a given society’.

In this section, I examine language ideology in the wider societal context, which provides insight in how people in Limburg rationalize, explain, and naturalize the use of Limburgish and Dutch in specific contexts, and eventually link Dutch and Limburgish to social types (Woolard Reference Woolard2016). To this end, I collected online readers reactions in De Limburger (see above). How readers react is in the words of Silverstein ‘a treasure-trove of spontaneous, reflexive reactions to a sociolinguistic phenomenon by an active, though lay commentariat’. (Reference Silverstein, Lacoste, Leimgruber and Breyer2014:175). Consider the following extract from a published letter in which the writer clearly evaluates where Limburgish—in his terms plat—should and should not be spoken.

Because talking plat is linked to being ‘among each other’. And that is perfect in situations at home, because there people are among each other. But not in various public situations. Here we are in The Netherlands, and we have our own language, we have to interact in that language in public life. (extract of a published letter in De Limburger, 11 November 2015)

The writer's opinion demonstrates the workings of language ideologies: Limburgish at home and privately among each other, and Dutch as the national language in public. This ideology naturally links The Netherlands including Limburg as a national territory to the use of Dutch. Dutch, in his view, ‘is a neutral vehicle of communication, belonging to no one in particular and thus equally available to all’ (Woolard Reference Woolard2016:7; see also Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts, Dirven, Frank and Pütz2003). Consider more extracts taken from letters of two readers (living in Limburg) published in De Limburger.

English, French, German, Spanish? Yes, that is an enrichment. But when I see some people on television who need subtitling due to their dialect, then I find that ‘language poverty’. And I find it pathetic when I hear some toddlers babble. (extract of a published letter in De Limburger, 15 April 2015)

The writer of this letter assumes that (i) a dialect is not a language, since it cannot be compared with standard ‘enriching’ languages like English, French, German, and Spanish; (ii) a dialect is not standard Dutch because it requires subtitling on national television; (iii) there is a natural link between unintelligibility (subtitling) and ‘language poverty’; and (iv) toddlers who use dialect do not speak properly but babble. The writer of this letter is clearly informed by the naturalizing force of language ideology that in contrast to national languages like English the use of a dialect is an embodied, emplaced practice and as such elicits a negative reaction, that is, ‘I find that pathetic’.

I, as a Limburger…. I find it disturbing when someone from a city in Holland settles in beautiful Limburg and expects us to adapt to him. That cannot be the case, according to me. One knows that a Limburger speaks his regional language, and we appreciate it if someone else tries to understand that. But most often one wants our beautiful landscape but not our culture! I plead for the broadcast of one's own regional language on regional radio and television. (extract of a published letter in De Limburger, 28 April 2017)

The letter starts by affirming the writer's construction of self as a Limburger who considers dialect an intrinsic part of regional/local culture, and natural in the construction of a Limburgian identity (Cornips & Knotter Reference Cornips, Knotter, Christen, Gilles and Purschke2017; and, in particular, Thissen Reference Thissen2018). Her message is informed by ‘an ideology of authenticity’, which holds that a language variety is rooted in and directly expresses the essential nature of a community or a speaker (cf. Woolard Reference Woolard2016). In addition, the writer emphasizes that someone from outside Limburg could learn to understand Limburgish but she remains reticent about the possibility that someone could learn to speak the language. Informed by this ideology, Limburgish is viewed as a language of expression rather than communication. Therefore, the extract expresses the sense that ‘[n]ot recognizing the language is not recognizing the language users’ (Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts, Dirven, Frank and Pütz2003:37).

The daily regional newspaper De Limburger mediatizes two contrasting but interdependent ideologies (cf. Woolard Reference Woolard2016) as follows. On the one hand, the newspaper regularly publishes articles in which Limburgish is part and parcel of arts and culture; it is newsworthy to report positively about artists performing in Limburgish on stage—theatre, pop music, opera—and in literature—poetry, novels; amateurs who compose dictionaries of various dialects; feasts that are considered local and unique to Limburg such as carnival (Thissen Reference Thissen2018); and local dialect spelling contests (Camps Reference Camps2018). On the other hand, reports dealing with Limburgish as a vehicle of daily communication are scarce. But if and when it happens, it is mostly mediatized in the context of education, in which it always competes with standard Dutch. For example, the editors of the newspaper De Limburger commented that speakers of Limburgish may exhibit low literacy and that transmitting Limburgish to new generations is solely the responsibility of the parents, that is, plat praten is een zaak voor ouders ‘speaking dialect is a parental issue’ (De Limburger 2016). In mediatizing these views, the editors’ opinions converge with the widely held view that the use of Limburgish is a private matter to be dealt with privately in the home by parents, and the monolingual ideology that the acquisition of Limburgish hinders proficiency in standard Dutch.

Let us consider two more extracts of published letters in De Limburger.

But the ever larger group of those that don't speak plat should also be taken into account, certainly in the city hall, in hospital, on television and in the library. Dutch is the common language in these places. What one speaks at home with one's mother is up to them. (extract of a published letter in Dutch in De Limburger, 25 April 2017)

Our economy, which is largely dependent on the global economic climate, has no interest in the Limburgian dialect. Someone who wants to preserve this cultural heritage has to do it at home or in associations. English and German have to be taught more intensively at schools, due to our geographical and international trade position. (extract of a published letter in Dutch in De Limburger, 31 July 2018)

The opinions voiced in De Limburger demonstrate that the ideology of anonymity and authenticity are two contrasting but interdependent ideologies (Woolard Reference Woolard2016), strengthening the belief that Dutch is devoid of emotion and culture, is neutral socially and geographically, and can be used in the context of economy and education. By contrast, Limburgish is devoid of the capacity of being used to transmit educational knowledge or the potential to promote economic and social mobility, and must therefore be limited to usage for heritage purposes and in the home for private interactions among people. The following letter in De Limburger addresses the preschool context.

We solved the issue! Just speaking Dutch in preschool, but dialect at home of course. (extract of a published letter in Dutch in De Limburger, 3 August 2018)

All of these letters are informed by a monolingual language ideology: in one domain—public, education, hospital, home, city halls—only one language should be spoken. Power dynamics ‘dictate’ that Dutch should be spoken in public and educational contexts, whereas Limburgish is allowed ‘behind the front door’ in the private domain, and to ‘perform’ culture and heritage in associations. The language ideology accounts for the asymmetrical political and societal values of Limburgish and Dutch in the public and home sphere.

Linguistic form: Language choices of parents and children in the home sphere

Survey studies also give an insight into respondents’ ideas and beliefs about their actual language practices and respondents’ answers provide a mediating link between ideology and practices. The first part of this section discusses very briefly two previous surveys covering respondents in Limburg who answered which language they use with their child(ren) at home. The second part describes surveys that I conducted in order to get a better grip on the linguistic impact that attending preschool has on home language maintenance.

Quite recently, two surveys questioning language use at home have provided figures on the transmission of Limburgish between parents and their children. In the first survey, 60% out of 712 respondents in Limburg reported bringing up their child in Limburgish or desiring to raise their child in it, as revealed by a survey commissioned by De Limburger in 2016, which indicates that the use of Limburgish is omnipresent in Limburg. The second large-scale survey analysed developments in the reported use of dialect versus Dutch from 1995 to 2003 throughout The Netherlands, including Limburg (Driessen Reference Driessen2006). Driessen contacted 600 Dutch primary schools, involving 34,240 pupils and their parents, using data from five measurement points of the national cohort study ‘Primary education’. His study showed that parents in Limburg reported the highest use of dialect between them and with their children in The Netherlands. A replication study provided results for 2011 (Driessen Reference Driessen2012). Table 1 presents the different percentages for the use of Limburgish according to different role-relations in the home sphere in Limburg. It reveals a significant decrease in the transmission of Limburgish in parent-child interactions over time, in particular between 2003 and 2011.

Table 1. Reported use of Limburgish in the home sphere from 1995 to 2011 (in %), taken from Driessen Reference Driessen2006/2012 (*see Driessen Reference Driessen2012).

I also took the initiative to conduct a Limburgish version of the Questionnaire for Parents of Bilingual Children (PaBiQ, COST Action IS0804; Tuller 2015) coordinated by Kirsten van den Heuij in the Limburgian branch of the so-called CoDEmBi (Cognitive Development in Emerging Bilingualism) project led by Elma Blom (Blom, Boerma, Bosma, Cornips & Everaert Reference Blom, Boerma, Bosma, Cornips and Everaert2017). It took the form of a telephone interview with the parents of 182 children in Limburg (sixty-eight girls, 114 boys) between the ages of four years, two months and eight years, ten months. For this article, I analysed who reported to use what language, that is, Limburgish and/or Dutch in the home sphere in Limburg.

Table 2 addresses the question as to which language(s) these 182 children were exposed to from birth onwards. All parents report that their child uses Dutch (100%), while 56% of the children were raised as bidialectal, that is, they were reported to speak Limburgish in the home sphere as well. Table 2 thus shows an asymmetrical relation: children may grow up monolingually in Dutch but never in Limburgish.

Table 2. Reported home languages by parents/caretaker(s) in Limburg (n = 182).

Parents were asked more details about who provides the input in Limburgish. The answers reveal an overwhelming number of families who provide Limburgish input: 145 out of the 182 families (80%, Table 3) reported that they spoke to their child in Limburgish. In most cases both father and mother reported using Limburgish to address their child (70%), and just one parent—father or mother—in a minority of the families (30%). Almost 20% of the families reported speaking Dutch only.

Table 3. Parents’ answers to the question ‘Who provides dialect input in the home?’.

Table 4 shows that thirty-six out of 145 families (25%) report that their child speaks Dutch only when Limburgish is a home language, even when (s)he is addressed in Limburgish by both parents. This differs from what is reported for Alsatian families discussed by De Houwer (Reference De Houwer, Cabrera and Leyendecker2017:233), where the lack of acquisition of Alsatian was higher if one but not both parents spoke the majority language at home.

Table 4. Parents’ answers to the question ‘What language does your child speak now?’.

Let us now consider a smaller written survey (n = 83), which I conducted in order to question the potential impact of preschool on the use of Limburgish at home, as reported by many (grand)parents (see the Introduction). The survey was conducted after I had given an oral presentation in the very south of Limburg in 2018, where fifty-eight grandmothers, nineteen mothers and one neighbour (n = 78, 92%) told me that their (grand)child(ren) and neighbour child attend(ed) preschool. The high percentage corresponds to the attendance rates of preschool in Germany and, according to Von Suchodoletz and colleagues (Reference Von Suchodoletz, Fäsche, Gunzenhauser and Hamre2014:510), it is relatively high compared to the United States and other countries. I first asked the (grand)mothers what language their (grand)child spoke before and after preschool at home. If we only consider the first three row options in Table 5 below, namely only Limburgish, only Dutch, and both Limburgish and Dutch, thirty-eight children spoke Limburgish (49%), twenty-two children spoke Dutch (28%), and eighteen children spoke both Dutch and Limburgish (18/78 = 23%) before entering preschool. The figures after entering preschool are: twenty-four children spoke Limburgish (35%), twenty-eight children spoke Dutch (43%), and fifteen children (22%) spoke Dutch as well as Limburgish.Footnote 8

Table 5. (Grand)mothers’ reported use of Dutch and Limburgish before and after attending preschool.

In sum, the reported exclusive use of Limburgish as home language decreased (from 49% to 35%) whereas Dutch increased (from 28% to 43%). Further, seventeen (grand)mothers (out of seventy-eight) reported that Limburgish and Dutch were spoken by teachers in preschool whereas forty-two (out of seventy-eight) reported that only Dutch was spoken (nineteen (grand)mothers showed a nonresponse).

Finally, I created a simple poll on Twitter inviting parents and grandparents in Limburg to answer the question as to whether their (grand)child stopped speaking Limburgish after entering preschool, as illustrated in Figure 2—the grandparents’ version (see Table 6). I realize that the question is suggestive, therefore I put the answer category nee ‘no’ in the first row.

Figure 2. Poll on Twitter.

Table 6. (Grand)mothers’ answers on a Twitter poll (1 August 2019).

Table 6 shows that about 30% of the (grand)parents believed that their (grand)child stopped speaking Limburgish after entering preschool. Of course a poll on Twitter attracts (grand)parents interested in the phenomenon of maintaining Limburgish as home language.

From the above, it is clear that surveys of intergenerational transmission of Limburgish between parents and children show a decrease over time (Table 1). However, the majority of Limburgish-speaking parents still report a readiness to bring their children up in Limburgish (De Limburger 2016), and when asked specifically about the language input in the home, the overwhelming majority of the children in the surveys is exposed to a Limburgish input (n = 145/182, 80%, Table 3). But these surveys also reveal that in 25% of the families, children are reported to speak only Dutch, even though Limburgish is provided by father and/or mother. It also becomes clear that toddlers who are raised in Limburgish are always raised in Dutch as well. There are monolingual Dutch-speaking children but never monolingual Limburgish-speaking children.

When asked about the impact of preschool attendance, which is very high in Limburg, (grand)mothers indicated as a group that the reported use of Limburgish as the home language had decreased from 49% before to 35% after preschool attendance whereas Dutch had increased from 28% to 43%, respectively. The simple poll on Twitter blows up the differences, that is, 30% of the respondents answer that their (grand)child stopped speaking Limburgish after preschool attendance.

However, quantitative surveys do not provide a direct link between preschool attendance and language shift by toddlers but actual languages practices do. The next section shows that Limburgish and Dutch are not ‘categories’ that are meaningful in themselves but ‘are analytically relevant only if and when the participants themselves make them relevant in a given interaction’ (Woolard Reference Woolard2008:435).

Language practices in preschool: Socializing in indexicalities of Dutch and Limburgish

Language ideology in the wider society and (acquisition of) linguistic form mutually shape each other as well as actual language practices (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985) in preschool. This is taken up in this section.

In Morillo Morales & Cornips (Reference Morillo Morales and Cornips2020) we examined actual language practices in three preschools in south Limburg between the end of February until July 2017, thirteen days in total. The interactions were recorded and fieldwork notes were made. The home languages of the children were Dutch, Limburgish, Turkish, Spanish, and Dari. In addition to teacher and child interactions, children in preschool interact highly frequently with their peers, in particular during free play or small-group classroom activities (Palermo et al. Reference Palermo, Mikulski, Fabes, Hanish, Martin and Stargel2014:1180). Teacher-pupil and peer interactions are crucial in order to address the research question since toddlers become socialized to agentively participate in communicative practices in Dutch and Limburgish ‘by a legacy of socially and culturally informed persons, artifacts, and features of the built environment’ (Ochs & Schieffelin Reference Ochs, Schieffelin, Duranti, Ochs and Schieffelin2012:4) in preschool.

Our findings revealed that in teacher-child interactions, toddlers as a group were always addressed in Dutch, whereas individual children might be addressed in Limburgish if this language was their home language. We analysed the teachers’ choice of Dutch as constructing a hierarchical formal setting, that is, teachers used Dutch when organizing the group of children and classroom in order to create routines and to draw children's attention and behaviour to learning. They also used Dutch to provide instructional support to ‘take children's learning to a higher level by connecting and building concepts and facts upon each other’ (Von Suchodoletz et al. Reference Von Suchodoletz, Fäsche, Gunzenhauser and Hamre2014:510). In these hierarchical contexts, socialization was a monolingual norm taking place through a discourse strategy: the teacher repeated Limburgish utterances by the toddlers in Dutch as the desired language code. The repetition or answering of a Dutch utterance by a Limburgish-speaking child in Limburgish by the teacher may happen, but only during free play outside or inside. In this way teachers provided emotional support in Limburgish, so as to create a sphere such that ‘children can take risks to explore the world and to develop autonomy and self-confidence’ (Von Suchodoletz et al. Reference Von Suchodoletz, Fäsche, Gunzenhauser and Hamre2014:510). Teachers knew exactly which child spoke Limburgish at home. Consequently, the toddlers learned to understand that the use of Dutch signalled that everyone present had to listen, whereas the use of Limburgish was interpreted as being an individual interaction between teacher and child. In this case, all other children were allowed to ignore the teacher. The language practices between teacher and child mirror language ideology in the wider societal context (see above) in that readers’ reactions in De Limburger revealed that Dutch is understood as devoid of emotion and culture, neutral and eligible in the context of education, whereas Limburgish is understood as a vehicle of emotion but devoid of the capacity to transmit educational knowledge and limited to usage in the home and/or for private interactions among individuals.

In peer interactions, Limburgish-speaking children were observed to switch to Dutch when interacting with predominantly Dutch-speaking children. The reverse did not occur. The asymmetrical power relation between Limburgish and Dutch-speaking toddlers also became transparent since Dutch-speaking children might interrupt Limburgish-speaking children (but not the reverse), whereas the former participated in the conversation when the same child used Dutch. The potential interruption by Dutch-dominant children reveals that young children may already experience significant pressure to speak the dominant language in preschool. Children probably anticipate peer rejection and/or exclusion from peer interactions, and negative evaluations by teachers as a result of their use of Limburgish, which might be stressful (Winsler, Burchinal, Tien, Peisner-Feinberg, Espinosa, Castro, LaForett, Kim, & De Feyter Reference Winsler, Burchinal, Tien, Peisner-Feinberg, Espinosa, Castro, LaForett, Kim; and De Feyter2014:753; Troesch, Keller, & Grob Reference Troesch, Keller; and Grob2016).

Preschool thus provides new language practices for the Limburgish-speaking toddlers. Teachers are experts in presenting information in a more formal and authoritative way (Aarts, Demir-Vegter, Kurvers, & Henrichs Reference Aarts, Demir-Vegter, Kurvers and Henrichs2016) than adults probably do in a family setting. Moreover, toddlers who leave the family and attend preschool for several hours a day come into contact with a new register, that is, academic language. This register is highly valued in the school context and is considered as the ‘mediating link between home language and literacy practices and (later) school achievement’ (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, Demir-Vegter, Kurvers and Henrichs2016:264–65). A good example is reading aloud from a book in preschool: this always takes place in Dutch. Furthermore, the 182 parents reported that they hardly ever read aloud in Limburgish (4%) at the expense of Dutch (99%). Reading aloud from a book and knowledge transfer in preschool expose children to a high degree of lexical diversity; they are expected to become more explicit, to talk about events outside the concrete here and now, and to elaborate on topics in a structured way (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, Demir-Vegter, Kurvers and Henrichs2016). The children were socialized in preschool to perform these activities in Dutch only.

Discussion

In this article several at first sight confounding factors are considered when we try to address the question as to why toddlers as young as two and a half may stop speaking Limburgish as their home language, and hence refuse to acquire or develop it any further after starting preschool, although their (grand)parents encourage them to speak Limburgish, and their teachers even use Limburgish at preschool. The language ideology in the wider societal context, the choice between the linguistic form of Limburgish and/or Dutch as reported in surveys, and the actual language practices in preschool (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985) provided a more holistic view to answer the research question. Language ideology in the wider societal context reveals that Dutch is seen as geographically and socially neutral and appropriate to use in public spheres—since ‘we live in The Netherlands’—devoid of emotion, and as the language of upward social mobility and school career. Limburgish, in contrast, is the language for private communication, for establishing relations ‘among us’ to be used in local cultural associations, and for cultural expression rather than communication, and as an expression of emotion and feelings as Limburgish is a ‘mother’ language. This language ideology informs and shapes teachers’ language practices in preschool. Dutch is used to transfer knowledge and to address all children who are expected to be attentive to the teacher. In contrast, Limburgish is used in private interactions between teacher and child, also to comfort the toddler, and children may ignore the teacher when they speak Limburgish. Influential and authoritative teachers repeat in Dutch what children utter in Limburgish. The observations also reveal that Limburgish-speaking children have to switch to Dutch when they interact with Dutch-dominant and other language-speaking children. However, the reverse does not occur: Dutch-dominant children were never observed to switch to Limburgish, not even when the teacher spoke Limburgish, which brings out a sensitivity to the asymmetry of speaking these two language varieties in the larger societal context (see also Nikoladis & Genesee Reference Nicoladis and Genesee1997).

The following factors appear to be crucial in answering the research question. First, attending preschool significantly increases peer interactions, and peers are ‘influential interlocutors’ (Verdon et al. Reference Verdon, McLeod and Winsler2014:170). Due to their cognitive and psychosocial development children are ‘differentially affected by different conditions and forces at different life-span stages’ (Troesch et al. Reference Troesch, Keller; and Grob2016:175). Young children in their one- and two-word stage experience more difficulties in engaging in peer interactions than older children because for the latter their oral competence is more developed to communicate effectively (Troesch et al Reference Troesch, Keller; and Grob2016). This might explain why preschool children at the age of two and a half are reported to stop using Limburgish but not children who enter primary school as the first educational context at the age of four. The age difference of two years between children entering preschool and primary school in The Netherlands ‘represent(s) developmentally quite different life stages’ (De Houwer & Ortega Reference De Houwer, Ortega, Houwer and Ortega2018:5). Second, the new educational context of preschool leads to novel types of interactions and role-relations and, combined with still ongoing developmental stages, these affect how children contribute their new language knowledge to new learner practices (Menyuk & Brisk Reference Menyuk, Brisk, Menyuk and Brisk2005:38) at home as well. Simply put, the more young children hear other persons like teachers and other peers (due to mobility of toddlers in voluntarily preschool) interacting in Dutch, and are exposed to more different sources of Dutch at the expensive of Limburgish, the greater the chance that these toddlers will acquire this language further (Place & Hoff Reference Place and Hoff2011), because they will find out that Dutch is indexed as the highest valued language in preschool. Moreover, toddlers who leave the family and attend preschool come into contact with a new register, that is, academic language, which is considered the ‘mediating link between home language and literacy practices and (later) school achievement’ (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, Demir-Vegter, Kurvers and Henrichs2016:264–65). In educational contexts such as preschool, children are exposed to a high degree of lexical diversity; they are expected to become more explicit, to talk about events outside the concrete here and now, and to elaborate on topics in a structured way (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, Demir-Vegter, Kurvers and Henrichs2016). The observed language practices (Morillo Morales & Cornips Reference Morillo Morales and Cornips2020) reveal that preschool children are socialized to experience, consider and treat Dutch, but not Limburgish, as an academic language. This corresponds to the societal perception that Limburgish is unfit for education and multiparty bidialectal interactions. Thus in preschool, Dutch, not Limburgish, gets the opportunity to mature further at all grammatical levels, including pragmatics. Finally, all survey data inform us that children who acquire Limburgish will always also acquire Dutch before the age of four, which is regarded as the crucial age for the question as to whether a child will attain proficiency in both languages (Unsworth Reference Unsworth, Nicoladis and Montanari2016:609). Thus these children are bidialectal, that is, Dutch is never a new language, neither in preschool nor in the home sphere. This implies that Limburgish-dominant children are very well aware that their parent(s) understand their Dutch at home. All of these factors impel the toddler to act in an agentic way in initiating a language shift to just Dutch in the home sphere. Hence, it is assumed that the indexicalities of Dutch for these toddlers are not so different from Limburgish in contrast to what both languages index for the adult speakers discussed earlier who only acquired Dutch as a second language outside the home sphere. For the toddlers discussed in this article, Dutch as a home language might index privateness and homeness similar to the use of Limburgish.

Summary

In this article, the concept of the total linguistic fact (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985) is applied in order to address the research question as to why toddlers as young as two and half years who speak Limburgish as a home language may refuse to do so after entering preschool and choose to speak Dutch only. I discussed how language ideology in the wider society, (acquisition of) linguistic form, and actual language practices in preschool mutually shape and inform each other (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Mertz and Parmentier1985), in order to account for why toddlers as agents might initiate a language shift. About a quarter of investigated parents in a survey about language choice in the home sphere reported that their children speak Dutch only if one or even both parents address their child in Limburgish. A smaller survey focussed on the impact of preschool, where (grand)mothers as a group reported a decrease in speaking Limburgish before and after preschool, although they all use Limburgish in the home.

Observations of language practices in preschool reveal an asymmetrical language choice pattern in which a monolingual Dutch norm becomes manifest through teachers’ repetition of Limburgish utterances in Dutch in situated contexts of instruction and transferring knowledge. Dutch, but not Limburgish, is elaborated as an academic language. All of these routines and socialization processes have a profound influence on language choice and the cultural, social, and cognitive development of young children who are still deeply engaged in the process of acquiring ‘language’, at home, in the wider society and in preschool through language (in) use. That children switch to Dutch in the home might be accounted for by power differences between indexicalities of the two language varieties in the educational setting. The power dynamics in preschool reveals social pressures on the Limburgish-speaking child to switch to Dutch by the dominant Dutch-speaking, same-aged peers, reinforced by teacher-pupil interactions and the use of Dutch by parents in the home sphere as well as media exposure. Thus, attending preschool shapes the effects of language ideologies in the larger societal context, and this has an impact as well on language choice by the toddler in the home sphere. Language ideology in the wider societal context revealed that Dutch for adult speakers in Limburg is indexical for engaging in the public and educational sphere; it indexes cosmopolitan and knowledgeable people while the adults’ use of Limburgish indexes privateness, intimateness, and emotionality. The indexicalities of both home languages for toddlers—that is, Limburgish and Dutch—may overlap, which is certainly not the case for contemporary adults (see Language ideology concerning Limburgish and Dutch). All of these factors drive the toddler to act in an agentic way initiating a language shift from Limburgish to Dutch in the home sphere that is quite an unknown phenomenon in the literature for children as young as two years of age.