Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had an intense impact on public health, health systems, and their response capacity on a global and national scale. 1,Reference Castro Delgado and Arcos González2 Emergency Medical Services (EMS), Reference Jaffe, Strugo and Bin3 hospital emergency departments (HEDs), Reference Alquézar-Arbé, Piñera and Jacob4 and primary health care systems Reference Rawaf, Allen and Stigler5,Reference Muñoz and López-Grau6 have been significantly affected. Reference Prezant, Lancet and Zeig-Owens7 Therefore, an emergency of these characteristics should demand reflection on the problems that have arisen and the solutions adopted by the health structures to create an opportunity to improve the adaptability of the health system to these situations.

Traditionally, EMS provides out-of-hospital care to critically ill patients through a network of mobile care resources and a coordinating center for emergencies that manages urgent health care demand and mobilizes resources, but these care dynamics changed during the pandemic. Reference Handberry, Bull-Otterson and Dai8 Before the pandemic, factors such as the aging of the population and the evolution of health care had already led to EMS integrating new functions and expanding its range of care programs (ie, care for time-dependent pathologies, care for chronic patients, and health information). This ability to adapt to changing environments, prior to COVID-19, has been able to facilitate EMS to adopt different roles during the pandemic, Reference Dami and Berthoz9 such as complementing surveillance systems and prediction of epidemiological trends. Reference Castro Delgado, Delgado Sánchez, Duque del Río and Arcos González10,Reference Levy, Klein and Chizmar11 On the opposite side, lack of planning and the absence of contingency plans in the EMS have revealed the lack of foresight in the face of problems that were already aware of, Reference Castro Delgado, Arcos Gonzalez and Rodriguez Soler12 and before which different measures had been adopted by the EMS. Reference Cabañas, Williams, Gallagher and Brice13

In Spain, there is an EMS in each autonomous community (in some of them, two) and the high degree of decentralization of the National Health System has meant that the problems that have arisen and their approaches have been different in each of them. It is a public financed EMS with no fee for the patient, as it is paid by national taxes. The aim of this study is to identify the problems perceived by medical and nursing professionals of EMS arising as a result of the first wave of the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2/SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Spain, as well as the measures or actions taken to manage these problems and improve response capacity.

Methods

This was an observational and cross-sectional epidemiological design study after the first wave of the pandemic using quantitative and qualitative methodology (mixed methods). Reference Creswell and Plano Clark14 In this way, one method provides support to the other and allows identifying subjective elements and combining them with objective data to provide a more complete general idea of the phenomenon studied, which is especially useful for studying more complex phenomena. Reference Taylor, Bogdan and Basic15

A self-administered questionnaire was designed, divided into three sections (Annex 1; available online only) that contained: (1) participant data (professional category, gender, years of experience in EMS, and current or previous management position); (2) 11 open-ended questions on aspects related to the pandemic; and (3) 15 questions on a five-point Likert scale (from one “Not at all” to five “Maximum”) on the management of the pandemic in their respective autonomous communities.

Using purposeful sampling, a questionnaire was sent and completed by 23 medical and nursing professionals, belonging to 13 EMS in Spain, previously identified as key informants and selected for having been linked to disaster response working groups or scientific societies. It was not possible to identify key informants with these characteristics in five of the EMS in the country.

In the descriptive statistics, absolute and relative frequencies were used for the qualitative variables, as well as means or medians (with 95% confidence intervals) based on the Shapiro-Wilk normality test for the quantitative variables. In the variables with a Likert scale, the median and IQR (interquartile range), error of the median, and coefficient of dispersion were calculated. The median test was used to compare medians with a significance level of P <.05. Stata v. 15.0. (StataCorp; College Station, Texas USA) was used for statistical analysis. Responses to the open-field questions were recorded and coded for further analysis. The study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the Principality of Asturias (Oviedo, Asturias, Spain; Ref.: 2021.570).

Results

Of the 23 participants, 12 (52.2%) were doctors and 11 (47.8%) nurses, with 16.3 years of mean experience (SD = 4.9) in EMS. Seven held management positions in the past, two did so at the time of the study, and another two both in the past and at present. The rest had no connection with EMS management responsibilities.

The variables corresponding to the 15 management items had normal distributions (0.914; P = .05 in the Shapiro-Wilk test). The mean score of the responses to the total of the 15 items referring to the management of the pandemic was 41.96 (95% CI, 35.9 - 47.9) out of a maximum of 75 points. Table 1 shows the median with its IQR, error of the median, and coefficient of dispersion of the scores for each of the 15 items on pandemic management. Table 2 shows the same data for each professional category and the comparison between both, with only one item with statistically significant differences (P = .039), the one related to their perception about EMS capacity to perform analysis to identify improvements in the event of pandemics, in which nurses scored higher.

Table 1. Score of the 15 Items Related to Pandemic Management

Abbreviations: COD, coefficient of dispersion; EMS, Emergency Medical Services.

Table 2. Comparison of Scores of 15 Items According to Professional Category

Note: Bold p-value = statistically significant.

Abbreviations: COD, coefficient of dispersion; EMS, Emergency Medical Services.

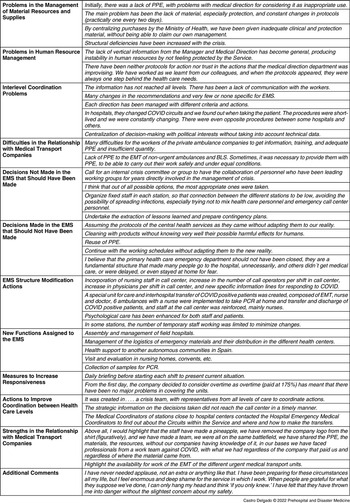

Table 3 collects the main comments on each of the items whose most relevant results are indicated below, grouped by items about problems detected and actions taken.

Table 3. Relevant Comments Made by the Interviewees

Abbreviations: BLS, Basic Life Support; COVID, coronavirus disease 2019; EMS, Emergency Medical Services; EMT, emergency medical technician; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Problems in the Management of Material Resources and Supplies

The main problem detected had been a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) or their poor quality, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. Only one interviewee stated that there had been no lack of PPE. Likewise, problems with vehicle disinfection procedures or changing protocols in the use of material resources were common in some EMS, the reuse of PPE had been raised as a problem, as well as the centralization of the purchase of PPE at a national level.

Problems in Human Resource Management

Lack of professionals, training deficiencies, and the hiring of professionals without EMS experience had been described by those interviewed. Other problems that had been repeated in different EMS had been the lack of communication with the direction and lack of interest of the management for their professionals; the excessive extensions of the working day had also been repeated in different EMS, as well as emotional exhaustion.

Interlevel Coordination Problems

A very operative problem described in inter-level coordination had been the problem of patient transfer in hospitals, as well as the lack of information to EMS professionals about changes in the different hospital procedures. The de-structuring of primary health care had also been an element expressed by several interviewees, which led to the EMS having to assume functions that were not their own, together with a lack of uniformity of criteria. Two interviewees stated that there had been no problems in inter-level coordination. Some interviewees also highlighted the politicization of technical decisions.

Difficulties in the Relationship with Medical Transport Companies

The main problem manifested by a large number of those interviewed had been a lack of specific training for Basic emergency technicians by their company, as well as a significant lack of material, especially PPE, and excessive decontamination times or lack of knowledge about cleaning protocols. Two interviewees stated that there had been no difficulties thanks to the excellent collaboration due to the exceptional situation that had been experienced.

Decisions Not Made in the EMS That Should Have Been Made

A large number of interviewees stated that it would have been necessary to work together with the working groups of mass-casualty incidents (MCIs) and disasters already established in many EMS. The lack of scheduled meetings was also a fact repeated by several interviewees. The initial absence of specific procedures and guidelines for their EMS, the need to improve the training received, and the lack of regular information to workers about the epidemiological situation and changes in procedures had been frequent perceptions, as well as the difficulty in making decisions. The establishment of epidemiological measures to control possible cases in the EMS had also been described by the interviewees, as well as the need to start to analyze the response to find improvement measures.

Decisions Made in the EMS that Should Not Have Been Made

In this case, the responses of the different interviewees were very heterogeneous. Among them, the rapid de-escalation of the actions undertaken by its EMS stood out. The reuse of PPE, the lack of adaptation of the protocols of the central health services to the reality of EMS, or the lack of reinforcement of logistical resources were also described.

EMS Structure Modification Actions

The main action to modify the structure of the EMS had been the expansion and reinforcement of the emergency call center, either by reinforcing the existing one or by creating specific centers for the management of COVID-19 calls. In some EMS, the figure of the epidemiologist had been implemented. Several EMS had created specific COVID-19 units, mainly Basil Life Support units (BLS), and some (few) had implemented measures to reduce the turnover of professionals through the different health care facilities or resources, and thus improved the control of occupational infections, while others had provided specific training about the call center to make professionals more versatile. Improving the cleanliness of the stations had also been a measure that was repeated in several EMS. The implementation of psychological assistance programs had been a measure of little general implementation, although specific programs had been developed in some EMS.

New Functions Assigned to the EMS

Among the new functions assigned to the EMS were performing protein chain reaction tests (PCR) at home or in nursing homes, support to the different field hospitals and alternate care sites for COVID patients, Reference Castro Delgado, Pérez Quesada and Pintado García16 logistical support, and the implementation of specific COVID-19 information telephones lines for the population.

Measures to Increase Responsiveness

Different measures were designed to increase response capacity, highlighting the reinforcement of the call center and the establishment of specific COVID-19 lines, the increase in BLS units, as well as the incorporation of nursing staff to the coordinating center and the creation of new Advanced Life Support units (ALS) and of specific BLS COVID-19 units. Other measures taken in few EMS were the establishment of a briefing meeting at the beginning of each shift or the improvement in the payment of overtime.

Actions to Improve Coordination between Health Care Levels

These actions were very heterogeneous among the different EMS. In some autonomous communities, inter-level committees were created and meetings of the station medical coordinators were convened with their counterparts from their reference HED. Some interviewees stated that they did not know of any specific action at this level.

Strengths in the Relationship with Medical Transport Companies

The main response had been the excellent personal relationship among staff and the teamwork of the different professional categories involved in emergency health care. Several interviewees emphasized the attitude of the emergency medical technicians (EMTs), which despite the shortcomings, had always been willing, collaborative, and professional.

Table 4 shows the main strengths and weaknesses identified based on the qualitative results.

Table 4. Main Strengths and Weaknesses Identified through Qualitative Results

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EMS, Emergency Medical Services; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Discussion

The results of this study are similar to those obtained in the qualitative study carried out among emergency personnel in Iran. Reference Mohammadi, Tehranineshat, Bijani and Khaleghi17 The initial shortage of PPE, the lack of procedures, and the lack of emotional support from those in charge are common elements that were found in the qualitative and quantitative data. The fact of the lack of PPE and the fear of contagion among EMS personnel has been found in other studies in Germany, Reference Dreher, Flake, Pietrowsky and Loerbroks18 as well as the training deficiencies in its use, Reference Cash, Rivard, Camargo, Powell and Panchal19 which increase stress among EMS professionals. Reference Ilczak, Rak and Ćwiertnia20 It is worth highlighting the important heterogeneity when it comes to raising weaknesses or actions for improvement, since aspects expressed by some interviewees as positive (for example, taking PCR samples) Reference Goldberg, Bonacci, Carlson, Pu and Ritchie21 are negative for others. This allows the affirmation that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the EMS without having previously established action procedures and a defined portfolio of services, which made it necessary for each EMS to make different management decisions, probably based on their professional background and personal experience of its directors, managers, and staff.

Analyzing both types of results together, the qualitative ones show a generalized dissatisfaction among staff with the way of tackling the first wave of the pandemic in the different EMS, something that is confirmed by the low scores in the quantitative results, mainly in the items that try to measure the integration of professionals in decision making, the lack of leadership from the directors, or the scant support perceived by the EMS directive structure, which coincides with what is stated in the qualitative items. Professionals perceive a lack of common lines of action, agreed and adapted to the prehospital environment, with little speed in the elaboration of procedures, little consensus, with little participation of professionals, and with a training program that could have been improved, in line with the results from other similar European studies. Reference Rees, Smythe, Hogan and Williams22 They believe that it is interesting to “undertake the extraction of lessons learned and prepare contingency plans,” but in the quantitative analysis, it was found that they doubt the ability to collect and analyze information to improve EMS adaptability. Other countries do carry out periodic analyses and recommendations on the adaptability of their emergency and emergency systems. 23 Some exceptions are found in some EMS, in which the direction developed adequate leadership and the professionals participated in technical decision making. The score above four was only obtained in the ability of professionals to adapt to the new situation. The explanation for this fact is found in the qualitative results, mainly in the item related to actions to modify the structure of the EMS, where different approaches are revealed, but also showing the personal effort made by health professionals. Other studies have also found an important implication of professionals in their daily work, even in pandemic conditions. Reference Eftekhar Ardebili, Naserbakht, Bernstein, Alazmani-Noodeh, Hakimi and Ranjbar24,Reference Alwidyan, Oteir and Trainor25

Clearly there was an initial lack of PPE, as stated in the interviews; this was solved and probably explains that the score on the Likert scale is above three. Among the decisions not taken, the one that draws the most attention is the low participation of health professionals in working groups, which coincides with the low score in the corresponding quantitative items. Few interviewees report the implementation of specific programs to monitor staff mental health in their EMS, despite the importance of proactively addressing this problem. Reference Xiong and Peng26 No interviewee has expressed ethical conflicts in the management of patients, something that has been found in other studies. Reference Torabi, Borhani, Abbaszadeh and Atashzadeh-Shoorideh27 The fact that significant differences were not found between medical and nursing staff in any of the study items could be interpreted as the results are very congruent.

Limitations

The main limitations of this article are those of qualitative studies, since it is not intended to make a statistical inference of the results, but to show a reality experienced by the professionals, together with the subjectivity of the interviewees, which is another limitation of these studies. The mixed-method methodology allows the qualitative results to be compared with the quantitative ones and thus minimizes the limitations, a fact that has been achieved in this study.

Conclusions

The conclusions that the study allows to be drawn are, on the one hand, that there is a general perception among respondents of a lack of support and communication from health care departments, and that staff experience has not been taken into consideration to make decisions adapted to reality, also expressing the need to improve the ability to analyze the EMS response. And on the other hand, that the EMS have adopted different measures to adapt to the pandemic, among which stand out the reinforcement of the call center, the creation of new resources, and the implementation of new functions. Finally, few respondents expressed general satisfaction with their EMS response during the first wave of the pandemic in Spain.

Conflicts of interest/funding

None declared. The authors have no financial or other interest that should be known to readers related to this document.

Acknowledgement

To RINVEMER (Red de Investigación de Emergencias Prehospitalarias - Network for Research in Prehospital Emergencies, Spain) for their support.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X22000462