Various elites in colonial Indonesia eagerly embraced the brand-new technology of photography from the second half of the nineteenth century onwards. Men and women commissioned photos to be taken, by professional photographers, of themselves, their families, and their surroundings.Footnote 1 The images were used for business cards and holiday greetings or were carefully arranged in family photo albums, thus turning photographs into three-dimensional and dynamic objects.Footnote 2 Colonial archives also contain photos of the mixed law courts where Indonesian, Dutch, Chinese and Indo-European men held judicial positions administering law over the non-European population of the colony. The law court photographs, the earliest dating back to the 1860s and the most recent from the 1930s, show a number of diverse individuals gathered and placed in an organized seating arrangement. The black-and-white images display how spaces—whether inside court buildings in the cities or outside in the countryside—were transformed into legal arenas via a plurality of people, paper, and cloth. The photos provide us with not only a breadth of information and a fascinating history of photography and law, but also indirectly grant access to other historical material visible in the photos. One of these is the range of textiles used in the courtroom, which are often not described in the written archives or always preserved, due to their fragile nature. Through a closer reading of photographs, we can see the use of cloth in the colonial courtroom.

The black-and-white stills caused color to disappear, but, in reality, the courtrooms were vibrant constellations. Indigo and brown kain panjang (long cloth, worn around the hip), yellow payongs (formal umbrellas), and a green tablecloth filled the space. The criminal cases tried by the regional mixed courts (the landraad) were often deemed of minor importance to those in power; in the photos, we only see the back or the side of local suspects and witnesses sitting on the floor, their faces turned away from the camera. Yet, considerable colonial correspondence and regulations were devoted to the careful curation of an amalgamation of the highest regional representatives of a variety of groups in the courtroom, including the cloth that was worn by these men, placed somewhere in the room, or draped over the table. Simultaneously, complex Javanese hierarchies were translated onto and through cloth, and its colors and patterns were used in the courtroom. Beyond being merely staged curiosities, or props, in a colonial courtroom that functioned as a “theatre play”—as this was how the photos were often described through the colonial gazeFootnote 3—the materials in the pictures reveal a courtroom of semiotic richness and plurality, where different actors were signaling distinct messages to multiple audiences. As is common in courtrooms, the placement of furniture and the location of judicial actors were used to purposefully emanate legitimate power and justiceFootnote 4. But in these mixed courts, it was the display of a pluralistic world and jurisdictional layering that mattered more than a monolithic reflection of state law.

Studying cloth here, with its visible and invisible messages, allows us to study the various layers of (mis-)communication that were inherent to a mixed courtroom filled not only with a number of objects but also a plurality of languages, symbols, political interests, and legal cultures. In her recent work, Laura F. Edwards presents a legal history of clothing in the nineteenth-century United States that gives a female perspective on what was considered valuable property needed to survive in a society, in particular a colonial one. She shows how both married and enslaved women could legally make a claim to textiles even though they had very limited claims to other kinds of property.Footnote 5 The value of cloth and clothing, whether it is predominantly financial or cultural, or both, provides an alternative archive and expands legal history conversations about the move beyond textual judicial sources that have in recent years emphasized the physical spaces in which legal ideas were formulated, including spaces outside of the courts,Footnote 6 as well as the hidden, yet central figures such as clerks and scribes in processes of lawmaking and legal practice.Footnote 7

The agency of local litigants, the work of indigenous legal agents, and geographical implications have increasingly gained attention in the study of colonial legal cultures and have shown the necessity of including spatial perspectives on law. The visual dimensions of lawmaking offer a distinct way to think about “doing law” in a colonial context. In Java, paper as a written document, proof of legal validity, or symbolic representation of a legal tradition, was important,Footnote 8 although less so in the context of criminal cases administered by the colonial mixed courts. It was the space of the court session, and the temporal moment within which the case occurred, that was of greater impact; here objects often spoke louder than words.

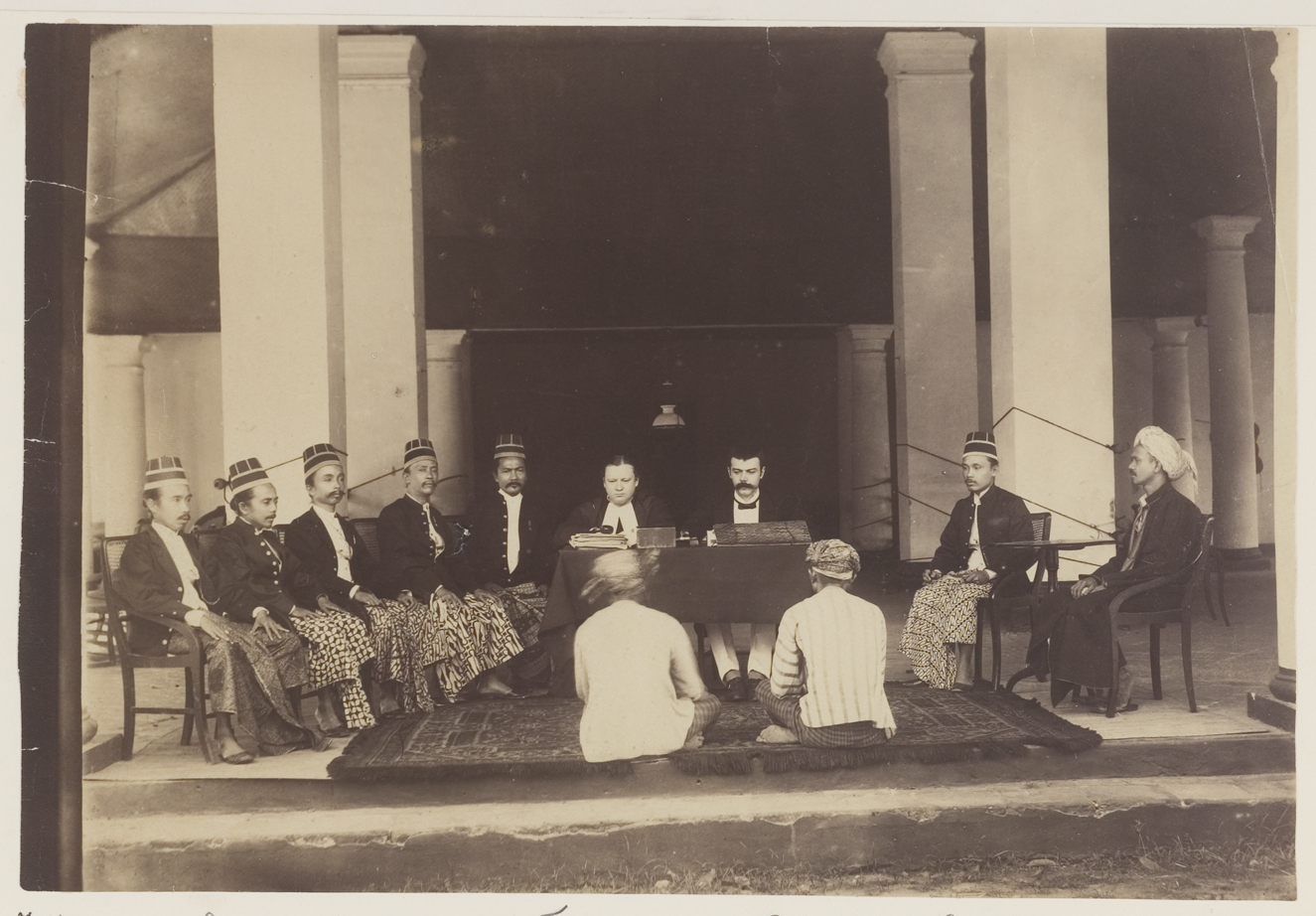

This essay will explore the textiles visible in four courtroom photos commissioned by Indonesian, Dutch, and Indo-European men in positions of power on the island of Java in the second half of the nineteenth century, taken by professional photographers, and with different aims for representation and preservation of the means and importance of the mixed courtroom. The first photo presented is the oldest surviving photo of a mixed court in Java. It was taken by the British photography studio, Woodbury & Page, in the 1860s, at the request of Adhipati Ario Tjandro Adhi Negoro (Tjondronegoro) of Pati in North Java (Figure 1).Footnote 9 One of his four sons, Hadiningrat, later vividly recalled the arrival of the photographer in the nearest large city, Semarang: “I was an apprentice of the first Woodbury, who arrived in Semarang around 1863. Photography back then was relatively harder, because one used wet plates and had to prepare everything yourselves. Nowadays, all this has become so much easier.”Footnote 10 While the young Hadiningrat learned about the techniques and art of photography, his father, Tjondronegoro, had photos taken of his four sons, his retinue, and himself, and, of course, of a (staged) law court session.Footnote 11

Figure 1. Landraad in Pati (Java, Indonesia), by Woodbury & Page, ca. 1865. Seated on chairs from left to right: Chinese Captain Oei Hotam; unnamed court member; court member Raden Adipati Ario Tjondro Adhi Negoro, bupati (regent) of Pati; president of the court P.W.A. van Spall; secretary (griffier) H.D. Wiggers; unnamed court member; penghulu (Islamic advisor) hadji Minhat. Leiden University Libraries, KITLV 3516.

The photo represents a court session of a landraad; a regional law court that administered mostly criminal and smaller civil cases involving Indonesians, Chinese, and other non-Europeans. In the larger Javanese cities, such as Batavia, Semarang, and Surabaya, court sessions took place in court buildings that resembled the neo-classical style of their European counterparts, such as the Council of Justice (Raad van Justitie), although on a smaller scale with less impressive pillars. At the landraad, the buildings were smaller, the procedures were shorter, and the punishments were harsher. In smaller towns in the countryside, landraad court sessions were held on the front porch of the house of the Dutch resident or in the pendopo (open meeting hall) of the Javanese bupati (regent), as in Tjondronegoro's photo.Footnote 12 Positioned fourth from left in the photo, Tjondronegoro looks directly into the lens. There are two other Javanese judges present sitting on chairs, flanked by the Chinese captain and the Islamic advisor, the penghulu at the left and right sides of the table, respectively. Seated at the center of the table is the Dutch resident presiding over the court, assisted by an Indo-European secretary. The jaksa (prosecutor) is standing on the left. Seated on the floor are several assistants with paper files laid out in front of them, while the two suspects are seated in front of the table with their backs to the camera. Also visible are thick law books on the table, papers piled up, a gown, a tablecloth, a Quran, hats, uniform coats, and decorative patterns on the sarongs of the Javanese court members. The umbrella carrier of one of the high-ranked court members peeks out from behind the table. What did the abundance of cloth in this courtroom make visible exactly? How? And to whom? How can we distil these messages from the materiality of the mixed courtroom?

Both the Dutch colonizer and the Javanese priyayi would use cloth as a means to strengthen their rule.Footnote 13 The Dutch court president would always ensure that the large table in the courtroom was covered with a green tablecloth, even when the court was organized outside, which, from a European perspective, represented a table where men of power made important decisions.Footnote 14 The Javanese population, perhaps over time, recognized the green tablecloth as a law court object, but inscribed their own meanings upon it. In post-colonial Indonesia, law courts continue to have green tables (meja hijau), although the color green is more commonly associated as being representative of Islam.Footnote 15 The verb “dimejahijaukan” (to be taken to the green table) means “to be taken to court.” In Suriname, another former Dutch colony, the expression “naar de groene tafel slepen” (to drag someone to the green table) similarly signals the continuation of the symbolic workings of green cloth.

Despite the emphasis on the green table as the centerpiece, the Dutch were not seeking to entirely reproduce a Dutch courtroom in their colonies. Instead, they saw strength in a plural courtroom where each legal actor—whether it be the prosecutor (jaksa), judge, clerk, or penghulu—was expected to wear their ‘traditional’ costume, meticulously described in the formal regulations (staatsblad). In Java, especially, the landraad with its abundance of court members, advisors, and officials in formal attire as well as its broad range of objects, consciously made visible colonial rule based on a system of “dual rule.” By the early nineteenth century, the sultanates of Cirebon (1445–1807) and Banten (1527–1813) in West Java and the outer regions of the central Javanese Mataram empire (1586–1755) had become “the government lands” of the Dutch colonial state. Only in the former center of Mataram, a geographically limited area referred to, in Dutch, as the “kings lands” (Vorstenlanden), the Sultan of Yogyakarta and the Sunan of Surakarta remained in place. The “government lands” covered most of the island however. There, a more direct colonial rule was executed while the pre-colonial regional elites, the priyayi class who had been local representatives of the Javanese kings and sultans, continued exercising their regional power. Tjondronegoro and his prestigious priyayi family strategically occupied several important bupati (regent; highest regional Javanese official) and chief jaksa (prosecutor) positions in nineteenth-century Java.Footnote 16 Specifically, the layers of cloth in the mixed courtrooms allowed for multiple ways of communicating in different legal languages. Jurisdictional layering was made visible in the courtroom through cloth. A black robe, a kain panjang, and a turban coexisted seemingly seamlessly, veiling the inequalities and contestations inherent to a colonial situation of legal pluralism.Footnote 17

For the priyayi, it was batik that was central to their cultural and political identity. Cloth in the Indian Ocean world has a long and rich history of international trade networks, with Indian and Chinese cotton and silk being traded to all corners of the ocean, including Java.Footnote 18 Cotton planting and weaving happened in Java, too, and was mostly for domestic use.Footnote 19 After 1800, Javanese textiles became less connected to Indian Ocean influences and were increasingly identified with the typical patterns and techniques of Javanese batik. North-coastal districts (pasisir) used more “gaudy colors” such as yellow, green, and red. Central-Javanese batik was predominantly deep blue and brown.Footnote 20 The most expensive batiks were made with a canting (a Central-Javanese technique executed with a hot-wax pen that would become dominant across Java after 1800), whereas the prominence of the Sundanese (Western Java) simbut technique using rice paste declined.Footnote 21 The Central-Javanese technique of using a canting, or wax-pen, meant that the patterns on the fabric were being “written” and could therefore be read, as Farish Noor has argued: “Batik is […] a form of visual and textual narrative that can be read (after all, batik is written, remember) and the answers to the questions that it poses before the eye of the modern viewer can be found in the material itself.”Footnote 22 A quick reading of batik in the Tjondronegoro photo, for example, immediately tells us that the Javanese law court member seated on the right is wearing a kain panjang with a pattern named ceplok, a geometrical rosette pattern of batik referring to his aristocratic lineage and position.

Batik patterns signaled the status and political power of the priyayi. A photo from Cilegon (Banten, West Java) in 1888 shows a dramatic example of this (Figure 2). It is a photo of an actual session of a circuit court (ommegaande rechtbank; a traveling mixed court for severe cases) held to convict the suspects of a large revolt in Banten. A number of Javanese priyayi and Dutch officials were attacked by protesting farmers during the revolt.Footnote 23 The Javanese court members in the photo were local priyayi who had been directly targeted. Some of the people revolting had been shot dead during the army's intervention, and others were tried by the circuit court, convicted, and sentenced to hard labor or death. Ninety-four locals from Banten, some of whom had been acquitted by the circuit court, faced a “political measure” (exorbitante rechten), and were exiled to another Indonesian island for an unspecified period of time.Footnote 24 The photo of the court session is one in a series of photos taken by a professional photographer, likely hired for the occasion, who had come from Bandung. News photography was not common yet, but the series of photos were clearly taken to cover the harsh punishment of the suspects in the revolt. Other photos in the collection show groups of prisoners and their punishment. Photos like these were later printed as lithographs in colonial magazines and newspapers, giving them news value.Footnote 25 Visibility was evidently important to the Dutch colonizer who largely ruled via the established authority of the Javanese priyayi. For the priyayi, this meant they were balancing a powerful yet precarious position. This photo could have been beneficial for either colonial government or priyayi messaging, or both. It is unknown who commissioned this photo in Banten. We do know that the photo was preserved in the family archive of the Sundanese Djajadiningrat family from Banten and published in the memoirs of Achmad Djajadiningrat whose father, Entol Goenadaja, was the wedono of Cilegon (third from the left). Achmad Djajadiningrat was still very young at the time of the revolt, but in his memoirs, he wrote: “Each morning I went to the court session with my father. I accompanied him to carry his documents and law books.”Footnote 26

Figure 2. Court session of a mixed court in Banten (Java, Indonesia), 1888. Seated on chairs from left to right: Court member Mas Ngabei Wirjadidjaja, patih of Anjer; court member Entol Goenadaja, wedono of Cilegon; court member Toebagoes Jachja, wedono of Kramatawoe; unnamed court member; court member Raden Mas Pennah; president of the court Mr. Heringa; secretary Mr. Blommestein; jaksa Mas Astrawidjaja; unnamed penghulu. Leiden University Libraries, KITLV 5300.

In the photo, Entol Goenadaja and other priyayi court members are wearing remarkably large “forbidden” (larangan) batik patterns on their kain panjang. The so-called “forbidden patterns” of batik originated from Central Java and were only allowed to be worn by aristocrats of high rank. In particular, the repetitive and wavy pattern of parang rusak is very visible. In the nineteenth century, parang rusak was one of the two remaining larangan patterns; the other was sawat. As was decided in the 1811 treaty between Raffles and Sultan Hamengkubuwono II of Yogyakarta, a batik with a parang rusak pattern would solely be a family cloth and could only be inherited. Parang rusak in Malay means “broken dagger,” although an alternative explanation is that it takes its name from the Javanese word pereng which translates as “slope of coral reefs.” In this explanation, the pattern would not display broken daggers, but rather high waves breaking on the coral reefs of the Indian Ocean in South-Central Java, near the Yogyakarta sultanate. An old legend told the story of Sultan Agung meditating while overlooking the Indian Ocean. Observing the waves slowly crashing against the cliffs provided him with the wisdom of persistence to overcome hard challenges.Footnote 27 In the context of punishing the participants in the Banten revolt, and the need for the priyayi to re-establish their power, this pattern was a logical choice. Besides, the large and repetitive pattern of parang rusak is meant to be seen (and read) from a “respectful distance,”Footnote 28 as in the courtroom where the suspects, witnesses, and audience observed the court members, seated higher on their chairs, from afar. In other instances, messaging through batik could be subtle and open to multiple interpretations. As a batik expert, Alit Djajasoebrata, who grew up in a Sundanese priyayi family, told me: “A specific batik pattern or detail on my kebaya (dress) could send a signal to one other person in the room without anyone else noticing.”Footnote 29 In the context of the courtroom, though, the distance between people was supposed to be a bit bigger. The suspects sitting on the floor—often alone because almost no one on trial in a mixed court could afford a lawyer—had to look up to see the faces of the men on the chairs. Yet, the pattern of the batik was right there in front of them at eye level. Parang rusak is often considered a rather rough pattern, not very refined at first sight, but powerful and aristocratic nonetheless (Figure 3).Footnote 30

Figure 3. Parang Rusak batik pattern, Yogyakarta (Java, Indonesia), before 1891. National Museum of World Cultures, Netherlands, RV-847-77.

Considering the Central-Javanese origins of parang rusak, it is remarkable that this photo was taken all the way across the island at the Sundanese West Coast in the former Banten sultanate. The port city of Banten had been a thriving international and cosmopolitan center of trade, with traders coming from all across the Indian Ocean, until the Dutch seized the port and established a trade monopoly in the seventeenth century and conquered the sultanates of West Java (Banten and Cirebon). The Mataram Kingdom (1582–1755) in Central Java was divided into four, and later two, with palaces in Yogyakarta and Surakarta, which increasingly focused their attention on the “preservation and development of their arts and cultural heritage and on maintaining the social hierarchy with its sophisticated rules through various forms of dance, theatre, puppetry, keris (dagger), literature, batik and culinary refinement.”Footnote 31 Whereas in Central Java, the Sultan of Yogyakarta and the Sunan of Surakarta remained in position, the Sultan of Banten was indefinitely expelled by the Dutch in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 32 The Central Javanese batik designs of the eighteenth century in cream, indigo, and brown would become the classical batik associated with the central Javanese rulers. Over time the Banten batik simbut was increasingly replaced by the Central Javanese way of batik canting, possibly under influence of the Djajadiningrat family.Footnote 33 Although priyayi would remain true to their regional batik traditions, batik also referred to their status and societal prestige. Java had an “overdetermined social environment” with a complex array of class, political status, language, religion, and connections: “Motifs and patterns of batik were used as markers of identity and difference.”Footnote 34 The Sundanese and the Javanese had ambivalent relations, but, in this case, the Central-Javanese batik served a purpose for the Sundanese priyayi whose power had been attacked so directly during the Banten revolt. By wearing these parang rusak patterns to court, Sundanese court members were signaling to the local observer their status and expertise as judges and priyayi as well as their kinship to Javanese rulers in Central Java.

Whereas the bottom and upper part of the priyayi uniform referred to Javanese hierarchies, the batik kain panjang (long hip cloth) and the black kuluk kanigara (hats)—the middle part of their uniform—indicated their connections to colonial rule.Footnote 35 In law courts, priyayi court members wore a black jacket, and, for special occasions, they changed into a blue coat. Their royal blue coats and decorations were meticulously described, in 1870, in colonial regulations, and changed while climbing the ranks of the colonial bureaucratic system.Footnote 36 A wedono, a person of middle-tier priyayi rank, would wear a royal blue coat with nine buttons each embossed with a crowned letter “W” and silver embroidery. His coat would be lined with yellow satin. All these details in the priyayi hybrid uniforms spoke to different, and sometimes overlapping, audiences, but were mostly unreadable by anyone outside of colonial Indonesia, and, in the case of the batik patterns, by most Europeans. It is telling that when a drawing was made of the Tjondronegoro photo by a Dutch artist for a Dutch audience, the batik patterns, and the exact color of the payong, were left out—they could not be read or translated by the Dutch—whereas the green tablecloth made its appearance (Figure 4). This drawing, in turn, would be the inspiration for a scene in the novel De Godin die Wacht, at least 30 years later, by Dutch author Augusta de Wit. The scene, describing a landraad session, effectively encapsulated the colonial gaze and gave the courtroom the feeling of a theatrical farce. The decorated screen in the photo and drawing, probably initially placed there by the photographers for a better photographic result, was described in the novel as a standard feature of a colonial courtroom providing “a suggestion of European order and comfort, contrasting strangely with the darkening shadows of real native life behind the fences of the courtyard at the back.”Footnote 37 The image of the landraad, through the interpretation of the client and photographer, and thereafter the Dutch viewers, artists, and an author was partially imprinted and formed by photography.

Figure 4. Drawing of the landraad of Pati, by Jeronimus, ca.1867. In: De Indische Archipel: tafereelen uit de natuur en het volksleven in Indië (texts by A.P. Gordon, D.W. Schiff, A.W.P. Weitzel et. al. Drawings and paintings of C. Deeleman, J.D. van Herwerden et al.), ed. Frederik Charles Theodorus Deeleman and S. van Deventer Jszn. (The Hague, 1865-1876), Leiden University Libraries, KITLV 47A69.

The fear of Javanese mysticism and silent force (stille kracht), supposedly threatening to undermine the colonial apparatus at any time, was not only vivid in De Wit's mind, but also in that of the Dutch officials, especially in the Javanese countryside. In the courtroom, this anxiety over invisible forces played out in the search for magical amulets that could be hidden in the headscarves of the witnesses. The amulet was understood to nullify the powers of the oath taken by the penghulu who was holding the Quran above the witness's head (Figure 5). A lie in the witness account would not hurt the witness anymore. Mirjam Shatanawi's research has found a remarkably large number of paper amulets stored in Dutch museums. They were sent to the Netherlands by Dutch colonial judges. In the Netherlands they were often not even opened, frequently dismissed as unassuming scribblings on paper.Footnote 38 Treated without the care, and without the fear—or at least emotion—that the Javanese and, indeed, the Dutch in Java had when they found them, these amulets are a reminder of the various forces that were ever-present in the landraad. Cloth became a place of concealment and magical power.

Figure 5. Court session of a landraad in Java, ca.1890. Exact location unknown, all persons depicted are unnamed. Leiden University Libraries, KITLV 90757.

This particular landraad photo, the third photograph in my analysis (Figure 5), is a highly curated scene. The photo is taken at the end of the nineteenth century in a studio in Batavia, and displays the oath-taking by the penghulu, staging a “typical” event from a landraad session. These photographs exemplify the colonial gaze par excellence. They emphasize the different and the exotic, centering the Dutch landraad president versus passive Javanese members. The suspects and witnesses sitting on the floor are wearing striped coats. This was lurik, a firm, woven, and striped cloth worn by rural Javanese men, unmarried women, and servants of the Sultan in Yogyakarta.Footnote 39 The lined pattern refers to service and humility. Or was it perhaps the photographer who made the choice, here in his studio, for the suspect to wear a striped coat as a reference to the European (not necessarily Dutch or Indonesian) understanding of striped prisoner's uniforms?Footnote 40

Around the same time, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as the landraad photos increased in number, landraden became less important to the highest Javanese priyayi. In an increasingly more complex and time-consuming colonial bureaucratic system, they would leave the landraad sessions to lower priyayi. The Dutch resident presiding over the landraad had by then been replaced by an “independent” Dutch judge, making the mixed courts less important to the higher Dutch administrative officials as well. The landraad turned into a more mundane place, a lower court from the perspective of the Javanese and Dutch administrative higher elites, and the courtroom became the realm of the new growing class of jurists in the colony instead. Photos taken of the landraad now became part of identity formation of colonial lawyers representing a street-level colonial power through law.

The final photo discussed in this essay (Figure 6) is preserved in a thick photo album in between family snapshots of the Indo-European family Du Cloux.Footnote 41 The landraad photo draws attention because there are only a few that show the professional work environment of the man of the family, Charles Philippe du Cloux. The rest of the album contains photos of a younger Du Cloux—his moustache grows more impressive with each passing year, and childhood photos of his wife, Mary Du Cloux-Halewijn, her sister, Annie, and their baboe (Indonesian nanny). There are photos of Indo-European men playing cards, an Indonesian servant carrying water, and two daughters growing up, with the turning of each page. Du Cloux was born in Pankalangbalei, near Palembang in South Sumatra. He studied law at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands. In his dissertation about the responsibilities of innkeepers for the property of their guests, the colonial Indonesian context is remarkably invisible, but in his last thesis statement (stelling) he refers to his Indo-European background when he states that only those with experience in the colony should be appointed as governor general of the Netherlands Indies.Footnote 42 Halfway through the photo album there is the landraad photo of Du Cloux after he had been appointed as landraad president in Banyumas (Figure 6). He is at the center of the landraad session surrounded by Javanese court members: the jaksa, penghulu, a guard and secretary. The names of the Javanese actors in these early twentieth-century photos in European and Indo-European family albums are almost always unknown.

Figure 6. C.P. Cloux (center), president of the landraad in Banyumas, during a court session, 1897-1903. Also depicted but unnamed are the Indonesian court members, jaksa, penghulu and secretary. Leiden University Libraries, KITLV no.119285.

Landraad presidents in these early decades of the twentieth century often complained that their work was not visible enough. In particular, those landraad presidents who thought of themselves as “fathers” who guided their “children” (by which they meant Indonesians) to a better path would complain about the assumed invisibility of the landraad. They would take photos of themselves in the landraad; “exotic” pictures, especially as new arrivals to the colony, and sent pictures to family in the Netherlands, showcasing the entire range of elites in traditional outfits. Meanwhile, in the colony, there was barely a European audience for the actual landraad case sessions. In contrast to sensational cases tried by the European Raad van Justitie (Council of Justice) when European victims or suspects were involved, and the spectator's gallery would fill up quickly, landraden were seen as spaces where only “boring theft cases” were tried. This was in spite of the fact that these courts held the power to impose severe punishments of up to 20 years of hard labor in chains.Footnote 43 Despite their relative invisibility, the landraad was not invisible to those whom it imposed its rule upon; the mixed courtroom continued to make colonial rule visible and tangible at the regional level.

And although the landraden became less prestigious, the importance of cloth in the space of these courts continued and the green tablecloth, as well as the hybrid uniforms, were still important elements of the courtrooms. Visibility of the colonial state remained crucial to the Dutch colonizer who continuously largely ruled via the established authority of the Javanese priyayi. Thus, when in 1920, the Association of Javanese Civil Servants requested that the government allow them to wear the white colonial costume that they usually wore when on duty (“om in het wit te mogen verschijnen”) during landraad sessions instead of their “traditional” costume, the request was turned down on the advice of the Supreme Court, which wrote to the director of justice: “The court finds that it (…) would harm the decorum.”Footnote 44

****

Photos of mixed courts in colonial Indonesia are catalogued in archival collections simply as a “landraad photo,” but each of the four photos discussed above belongs to a different genre and tells a distinct story about imperial law, mixed courts, and legal pluralism. There were photos commissioned by Javanese members of the courtroom to express their political identity, there were those commissioned for purposes of colonial propaganda and to reinforce power, some were taken in a photo studio to stage a “typical” event from the colony, and others were personal photos, taken at the request of Dutch or Indo-European landraad judges, to send to family in the Netherlands and elsewhere, showing their workplace. In each of these photos, the visual staging of the landraad through cloth provides us with an alternative archive offering new venues to explore the workings of legal plurality in a colonial context. It reveals and draws attention to a jurisdictional layering that productively questions the binary of direct and indirect rule.

The green color of the tablecloth, the batik design on the outfits of the Javanese court members and their hybrid uniform coats, the headscarves and striped coats of the suspects, the turban of the penghulu, and the black gown of the landraad president: although these photos do not reveal everything, they add new materials and voices, especially those of the local court members and other local actors who are hardly mentioned in the written colonial sources. The photos are so abundantly “filled” with people, paper, and cloth, that we constantly change the aperture, to focus on something or someone else. What one observer might see, the other might not. And this would not have been so different at the time. The material objects in the courtroom sent their own distinct messages and signals, sometimes tailored for the entire audience, sometimes only for certain observers. The plurality of cloth provided possibilities to impose colonial rule, to insert oneself (simultaneously) in an alternative hierarchy or to resist.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Alit Djajasoebrata, Liesbeth Ouwehand, and Anouk Mansfeld for conversations and for providing access to collections, as well as Gautham Rao and the anonymous Law and History Review reviewer for their comments.