‘I dare to say I am like no one in the whole world,’ Anne Lister wrote in her diary in 1823. A ‘curious genius’ from the cradle on, a prodigy known as the ‘Solomon’ of her school, Lister grew up to be an individual remarkable for, and self-aware about, her individuality – what she called her oddity. She knew her ‘softly gentleman-like’ manners were distinctly ‘peculiar’, and sounded wryly amused about the odd freak Nature must have been in when she made Lister.

These phrasings aren’t just euphemisms for – though they include – gender nonconformity and lesbian desire. Anne Lister was singular in many ways, and even when she could be seen as a type (self-educated lady, say, or Tory landowner on the border between yeoman and gentry), she combined her affiliations unpredictably. Those of us who have been drawn to Lister over the past two centuries, to investigate and write about her, have found different aspects of her most urgently interesting, but I think we all treasure her queerness, in the broadest sense.

In the twenty-first century, Lister has become so much more than an individual. Her archive has bloomed into a cultural phenomenon that includes not just one of the longest diaries in the English language, plus letters, travel journals, and reading and lecture notes, but prose, theatrical and televisual fictions of her life and times, most notably the TV series Gentleman Jack, which has provoked everything from Yorkshire tourism to online community and controversy.

As someone who has been fascinated by Anne Lister and written about her on and off for more than three decades, I am delighted to see the ripples made by her life spread farther and farther. I appreciate her not just for her own odd self but for the peephole her eloquent diaries cut into a hidden world of sociability and sexuality; not just for the path she negotiated through early nineteenth-century English society but for the ways that her some dozen lovers and crushes lived their varied lives. Lister logged everything from prices to gossip to coal mining to masturbation with a relentless hunger for understanding that I can only call libidinal, so her writing throws shafts of new light in all directions.

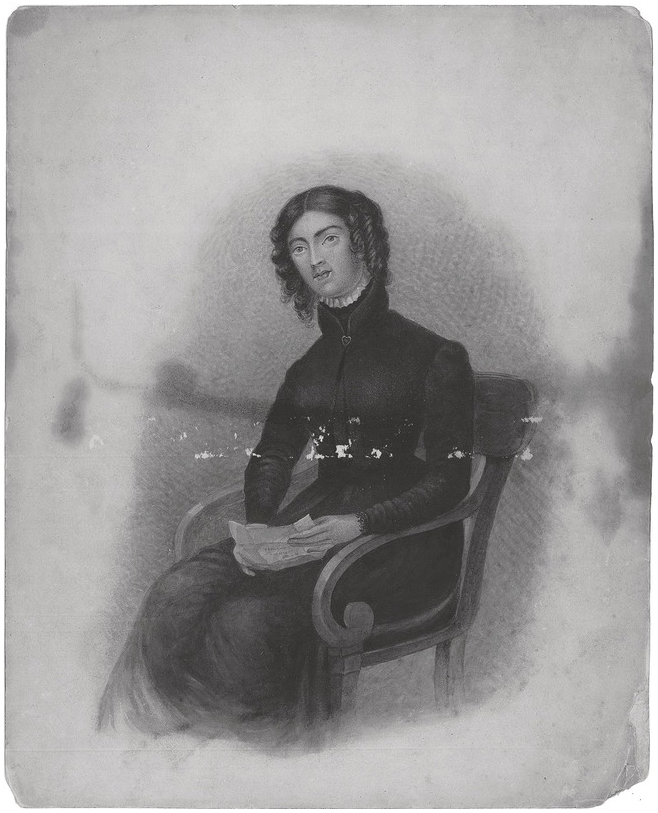

Figure 1 Anne Lister portrait (c.1822). West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale, sh:2/m/19/1/1.

A free spirit who defied gender norms, but also a conservative snob, coldblooded as often as she was passionate, Lister boasted of her consistency, but could be inconsistent to the point of hypocrisy. She vaunted her candour, but lied to her family, friends and intimates, and used fictional techniques to rework the past in her diary. Long after her ‘crypt hand’ code was broken and her handwriting puzzled out, Lister’s paradoxes require interpretation; like an onion, she has layers all the way down.

Perhaps quarrels over which descriptive labels to choose for Anne Lister on plaques marking key locations in her life will always have something absurd about them, because this protean, polymorphous figure would need a mile-wide plaque to begin to describe her properly. This book – the long-overdue first collection of research essays on Lister – is an excellent start at making sense of a phenomenon that will still be demanding decoding for centuries to come.