Introduction

Dementia has risen to political prominence in recent years driven by concern over the international scale and projected increase to the numbers of those affected by the condition. In the United Kingdom (UK), an estimated 850,000 people have dementia (Alzheimer's Society, 2017), around two-thirds of whom remain in their own homes (Alzheimer's Society, 2013). The World Health Organization predicts global numbers living with dementia will increase to 75 million by 2030 and to 132 million by 2050, noting that dementia is one of the major causes of disability and dependency of older people (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2015; World Health Organization, 2017). The response in many Western nations has been to shift dementia care from institutionalised settings to the neighbourhood. Not only has this meant passing many of the associated costs from the state to families (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Zhu and Clipp2001; Wittenberg et al., Reference Wittenberg, Knapp, Hu, Comas-Herrera, King, Rehill, Shi, Banerjee, Patel, Jagger and Kingston2019) but also that families care for longer and increasingly rely upon their support networks (Dam et al., Reference Dam, Boots, Van Boxtel, Verhey and De Vugt2018). Hence, both the ‘where’ and the ‘who’ of the provision of care and support is changing, sparking growing interest in the geographies of dementia care and raising questions over the shifting spatial and social experience of the condition. Yet, limited research currently exists that captures the neighbourhood-based experiences of living with dementia (Keady et al., Reference Keady, Campbell, Barnes, Ward, Li, Swarbrick, Burrow and Elvish2012). We need to understand better how people living with dementia are themselves meeting the challenge of these changes and to what outcomes they might be leading.

From a policy perspective, an emerging ‘dementia-friendly communities’ agenda (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2017; Hebert and Scales, Reference Hebert and Scales2019) represents a shift from biomedically led approaches that have tended to treat location as secondary to effects of the disease and the management of symptoms. Across the UK and internationally, efforts have begun to focus on community-based responses through a programme of awareness-raising, enhancing accessibility of the built environment and the redistribution of care (British Standards Institution, 2015; Alzheimer's Disease International, 2020). Writing of a similar agenda in the field of learning disabilities, Power (Reference Power, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014) argues such changes might be read as an effort to reconfigure the social ecologies of individuals who rely on support, orienting away from the support of formal practitioners and towards more ‘naturally occurring’ neighbourhood connections with retailers, service-sector operatives, neighbours and such-like. The emergence of neighbourhood-based caring arrangements creates new spaces of care and potentially new forms of sociality (Pols, Reference Pols2016). However, the mounting critique of policy-driven efforts to engineer change has drawn attention to significant levels of unmet need for people living with dementia in the neighbourhood, and for their care partners (Van der Roest et al., Reference Van der Roest, Meiland, Comijs, Derksen, Jansen, Van Hout, Jonker and Dröes2009; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Samus, Morrison, Leoutsakos, Hicks, Handel, Rye, Robbins, Rabins, Lyketsos and Black2011; Von Kutzleben et al., Reference Von Kutzleben, Schmid, Halck, Holle and Bartholoeyczik2012; Morrisby et al., Reference Morrisby, Joosten and Ciccarelli2018; Black et al., Reference Black, Johnston, Leoutsakos, Reuland, Kelly, Amjad, Davis, Willink, Sloan, Lyketsos and Samus2019). This research tells us that it is less medical or clinical needs that remain unmet and instead the struggle to manage day-to-day challenges of finding company and opportunities for sociability, managing the home and finances, and engaging in meaningful activity (Miranda-Castillo et al., Reference Miranda-Castillo, Woods, Galboda, Oomman, Olojugba and Orrell2010; Crampton and Eley, Reference Crampton and Eley2013). Clearly, research is needed that looks beyond the domain of health and social care to explore the vicissitudes of day-to-day living for people with dementia.

In this paper, we report and discuss findings from a study that went behind policy headlines and ambitions to consider the realities of day-to-day neighbourhood living for people with dementia. The ‘Neighbourhoods: Our People, Our Places’ (N:OPOP) study is a five-year, qualitatively led, international investigation jointly funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research (UK). Our aim here is threefold: first, to understand better what it is like to live with dementia in a neighbourhood context; second, to interrogate current understanding and explanations of this experience; and third, in light of our findings, to outline an alternative narrative and interpretation to guide future policy and practice.

The relationship of person (with dementia) and place

Existing commentaries have claimed that when living in a neighbourhood context, people with cognitive impairment face the prospect of social withdrawal and gradually constricting boundaries to the geographical reach of their day-to-day lives. Duggan et al. dubbed this process the ‘shrinking world’, and noted:

Our findings suggest that declining memory, confusion, disorientation, reduced confidence and anxiety are all interlinked. These factors can impact significantly on the use of the outdoor environment by people with dementia by restricting and limiting the areas which they access and reducing outdoor activity. (Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008: 197)

Such arguments both reflect and build upon theories of ageing as a dynamic relation of environmental press and personal competence (Lawton and Nahemow, Reference Lawton, Nahemow, Eisdorfer and Lawton1973) where progressive impairment and frailty lead to individuals adapting the reach of their day-to-day lives. The authors go on to argue that moving within ‘gradually smaller areas’ is likely to be experienced as a loss of independence and control. Subsequent research using GPS technology to compare the ‘out-of-home behaviour’ of people with and without cognitive impairment has similarly charted a decline in spatial activity for those living with dementia (Shoval et al., Reference Shoval, Wahl, Auslander, Isaacson, Oswald, Edry, Landau and Heinik2011), suggesting that such change may serve as an early indicator of the onset of dementia (Wettstein et al., Reference Wettstein, Wahl, Shoval, Oswald, Voss, Seidl, Frolich, Auslander, Heinik and Landau2015). More recent interview-based research has, however, questioned the suggestion of a steady decline in outdoor activity, arguing that a more nuanced picture is emerging, but nonetheless found reduced participation in public space by people with dementia and changes to the destinations/venues occupied outside the home (Gaber et al., Reference Gaber, Nygård, Brorsson, Kottorp and Malinowsky2019).

The notion of a shrinking world is more than a descriptor of individual and shared experience and has been presented as an explanatory framework by which to understand the origins and nature of the changes occurring. It suggests that a growing move to localisation (i.e. becoming increasingly focused both socially and spatially on the immediate context surrounding the home) occurs as people adapt to the progression of dementia and plays out at an individual level of private struggle. This narrative represents an ‘impairment-led’ approach to understanding a person's relationship to place, and which treats space as a container of experience. From this perspective, the home and neighbourhood are assumed to pre-exist the individual's struggle and are understood as largely fixed and stable in the face of changes experienced at an individual level.

A growing body of qualitative research has added to our understanding of the person–place relationship through a focus on the meaning and experience of neighbourhood living with dementia. A prominent theme across much of this work concerns the significance attached to familiarity, and the association with comfort and safety as reported by people living with dementia (e.g. Brorsson et al., Reference Brorsson, Ohman, Lundberg and Nygard2011; Von Kutzleben et al., Reference Von Kutzleben, Schmid, Halck, Holle and Bartholoeyczik2012; McGovern, Reference McGovern2017; Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Burton, Leverton, Herat-Gunaratne, Beresford-Dent, Lord, Downs, Boex, Horsley, Giebel and Cooper2020). By contrast, unfamiliar settings and situations are often perceived as risky, engendering discomfort and even distress (Sandberg et al., Reference Sandberg, Rosenberg, Sandman and Borell2015). This emerging multi-disciplinary body of research indicates that familiarity is a multi-faceted phenomenon, for instance depicted in design-led studies as tied to material features of the built environment (Blackman et al., Reference Blackman, Mitchell, Burton, Jenks, Parsons, Raman and Williams2003; Burton and Mitchell, Reference Burton and Mitchell2006). Whereas, in studies of how people with dementia tackle challenging situations in public spaces, Brorsson et al. (2011: 592) have argued that familiarity exists as ‘an inner feeling of recognition’ part of a person's engagement with place that promotes comfort and reassurance. Research also suggests that familiarity is an unstable feature of the relationship that a person with dementia has with their surroundings, it can be lost, sometimes quite suddenly (Sandberg et al., Reference Sandberg, Rosenberg, Sandman and Borell2015). People with dementia have described losing their grip on ‘basic familiarity’ (Van Wijngaarden et al., Reference Van Wijngaarden, Alma and The2019), drawing attention to the unpredictable and unstable nature of place (Brittain et al., Reference Brittain, Corner, Robinson and Bond2010; Clarke and Bailey, Reference Clarke and Bailey2016) which at times can prove destabilising (Lloyd and Stirling, Reference Lloyd and Stirling2015; Bartlett and Brannelly, Reference Bartlett and Brannelly2019).

Taken collectively, we argue this work offers the potential for an alternative interpretation of the person–place relationship in a dementia context. Rather than understanding a person's experience as unfolding ‘in place’, instead place is produced through the way a person engages with their surroundings, and we argue this has particular implications for how we construct a narrative of dementia and neighbourhoods.

Neighbourhoods as relational places

In this paper, we build on earlier analysis of findings reported from N:OPOP that highlighted the value of understanding neighbourhoods as relational places in the lives of people with dementia. Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Campbell, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2020) argue the interconnected nature of people's lives transcends more traditional notions of neighbourhoods as bounded spaces. Taking everyday technology as an example, the authors show how a person with dementia can reach out to significant people using digital technology, overcoming geographical distance to ensure a continued presence in their lives, thereby revealing how local spaces can be both ‘compressed and stretched out entities experienced at different scales’ (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Campbell, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2020: 4). A relational lens disrupts assumptions about what constitutes ‘the local’, indicating that presence is not reducible to ‘co-presence’ (Callon and Law, Reference Callon and Law2004) and challenging understandings of neighbourhood as tied to a particular scale of activity or place (Marston et al., Reference Marston, Jones and Woodward2005).

A relational understanding also emphasises the fluid, open-ended nature of the neighbourhood. Writing in the field of mental health, Tucker (Reference Tucker2010: 526) argues that a relational lens ‘raises questions as to the formation of perceived stability within everyday life’. Tucker argues that recognising the fluid and changing nature of place helps to understand how stability in the lives of people with mental illness is an achievement rather than a pre-existing property of place. Tucker draws attention to the repeated and habitual spatial practices in which his research participants engage, which serve as ‘anchor points’ in a context of fluidity and instability. ‘Such activities stabilise the space, organise it in such a way that produces life as comfortable’ (Tucker, Reference Tucker2010: 531). For many of Tucker's participants, variation and unpredictable change pose a continual threat which they manage through the repetition of certain routine practices. This line of argument has direct relevance to our efforts to interrogate and problematise the ‘shrinking world’ narrative. A relational lens turns this conception inside out, by highlighting that people with dementia face an ongoing challenge of creating stability in a context of flux and change, and in so doing are engaged in a process of making and re-making place.

In this paper, our aim is to challenge an ‘impairment-led’ explanation for the relationship between people with dementia and their neighbourhood as encompassed in the notion of a ‘shrinking world’. We argue for a different way of understanding the process of ‘localisation’, not as an inexorably constricting boundary to a person's world but rather as a set of place-related practices by which ‘the local’ is produced and continually remade. As such, our argument aligns with a growing emphasis upon a ‘capacity-oriented’ approach to dementia. The notion of social health has been used to rethink the experience of the condition (Vernooij-Dassen et al., Reference Vernooij-Dassen, Moniz-Cook and Jeon2018), highlighting that health is never fixed or stable but dynamic, and for anyone living with a chronic condition, involves ongoing adaptation and management (Dröes et al., Reference Dröes, Chattat, Diaz, Gove, Graff, Murphy, Verbeek, Vernooij-Dassen, Clare, Johannessen, Roes, Verhey and Charras2017). Our argument here is that whatever role the neighbourhood has to play in this process, it is how people engage; the practices they adopt and adapt that are vital to the everyday struggle of living with dementia.

A focus on social and spatial practices

Examining social practices provides a useful way to understand how people adapt to life with dementia and the mechanisms behind that adaptation. Social practices are a situated endeavour where meaning, material and competence intersect (Shove et al., Reference Shove, Pantzar and Watson2012). They exist as discrete entities with a history to their development and as carriers of meaning at a collective and cultural level (Shove et al., Reference Shove, Pantzar and Watson2012). As an entity, a social practice is distinct from any one moment of its performance, and Maller (Reference Maller2015) argues this is important to the field of health and wellbeing because it draws attention away from the individual as an agent of change, problematising long-standing efforts to engineer change through a focus on the ‘ABC’ of attitudes, behaviour and choices. By decentring the individual, a focus on social practices avoids moralising narratives of personal responsibility and instead helps us to understand how the materiality and sociality of people's worlds are translated into outcomes for health and wellbeing through the practices to which people are recruited.

Attending to social practices helps us understand how place is continually made and re-made, unfolding in time more as a kind of ‘place-event’, than a fixed set of stable properties (Massey, Reference Massey2005). Thus, Shove et al. (2012: 13) argue that ‘stability is the emergent and always provisional outcome of successively faithful reproductions of practice’. Relevant to our discussion in this paper, Pink (Reference Pink2012) asserts that analysis of everyday situated practices provides a route to understanding and theorising the familiar. Her argument echoes that of Shove et al. (Reference Shove, Pantzar and Watson2012) in suggesting that we understand familiarity as an achievement, and an outcome or product of practice. Focusing on activities in the home and neighbourhood, Pink shows that repetition of mundane practices lies at the heart of how people manage everyday life and adapt to the continually shifting conditions it presents. Yet, such practices can also be a source of change. Warde (Reference Warde2005) argues that practices carry the ‘seeds of constant change’ and are always open to re-working and tailoring to particular situations. Adaptation to a situation also occurs as a person abandons certain practices while adopting or being recruited to others. This notion of recruitment is important because it underlines the central role of social networks as contexts for exposure to new ways of doing and for the transmission of skills that enable people to participate (Alkemeyer and Buschmann, Reference Alkemeyer, Buschmann, Hui, Schatzki and Shove2017). In this paper, our aim is to focus upon practices and their constituent elements that are shaped by and relevant to living with dementia in a neighbourhood context.

The project

The N:OPOP study (2014–2019) was undertaken as part of a wider programme of research exploring dementia in a neighbourhood context (Keady, Reference Keady2014). The research was intended to inform commitments set out in the Prime Minister's Challenge on Dementia (Department of Health, 2012) which included plans to develop a nationwide network of dementia-friendly communities. The project built on a pilot study involving 14 carers of people with dementia, conducted in the north-west of England during 2011 (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark and Hargreaves2012). This allowed us to test the feasibility and refine the design in collaboration with stakeholders, using workshops that included people with dementia, carers, practitioners, service commissioners and local policy makers.

Design and methodology

The main aim was to investigate how neighbourhoods and local communities can support people living with dementia to remain socially and physically active. Working within a social constructionist paradigm, we used qualitative methods framed by a longitudinal and comparative design. The project extended over three fieldsites: Greater Manchester in northern England; the Central Belt of Scotland; and the county of Östergötland in the south of Sweden. Each fieldsite incorporated a research phase followed by planning and development for a neighbourhood-based intervention.

Mixing qualitative methods

Across all three fieldsites, walking interviews were used to engage in in situ discussions where participants were asked to take the researcher on a preferred or commonly used route through their neighbourhood. As discussed by Kullberg and Odzakovic (Reference Kullberg, Odzakovic, Keady, Hyden, Johnson and Swarbrick2018), walking involves bodily movement and synchrony, creating a connection and space for spontaneous conversation about the social and material aspects of the neighbourhood (see also Phillips and Evans, Reference Phillips and Evans2018). A walking method is well-suited to the participation of people with dementia as the focus for our discussions was often readily to hand, providing immediate and material prompts to support narratives of neighbourhood life. The UK fieldsites also employed home tours, which drew upon Pink's (Reference Pink2009) ‘walking with video method’, and which were either filmed or audio-recorded. Here, the participants took us on a tour, moving through different domestic spaces, pointing out and even handling objects of significance. In both the neighbourhood walks and home tours, the person with dementia led the process, some even adopting the role of tour guide, sharing anecdotes and histories of the places we passed through. Walking together enabled us to study a moving research subject ‘through an embodied and sensory engagement with the practices and places’ of the people we were interviewing (Pink, Reference Pink2012: 33).

We also used social network mapping while visiting participants at home. These were open-ended interviews with ‘mapping’ used as an elicitation device to explore social connectedness and the everyday give and take of help and support. This method introduced participants to a relational and affective practice of visualising support, providing opportunities for reflection, while co-producing an ‘affective artefact’ to inform the analysis process (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Clark, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2019). The mapping interviews were sometimes led by care partners because of the emphasis on recall but were often carried out jointly and where possible led by the person with dementia.

Taken collectively, the mix of interviews allowed us to explore the social, material and affective dimensions of neighbourhood living for people with dementia. Returning to many of our participants after a break of 8–12 months, we were also able to deepen our understanding of the temporal dimension by repeating the walking and mapping interviews for a second time.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the NHS Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee in the UK and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (the county of Östergötland, Sweden). A process consent approach (Dewing, Reference Dewing2008) was followed and we were guided throughout by the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act (Department of Health, 2005) and Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act (Scottish Government, 2000).

Analysis

We gathered mixed-media data that reflected the multi-dimensionality of people's relationship with their neighbourhood. Informed by facet methodology, the ‘data were interrogated along question-driven or insight-driven routes across and between the [different] facets’ (Mason, Reference Mason2011, p. 83). There were five main steps to analysis of the interview transcripts: we began with open coding of the first ten cases from each fieldsite (a case being one round of interviews, usually a walking interview, social network mapping and a home tour). From this we developed a coding framework. The team then collaborated in selecting 15 case studies from each fieldsite (this included interviews from both rounds of interviewing where available). Case study selection aimed to cover a diverse mix of settings and situations including people living with different types of dementia and those living both with and without a co-resident carer. These case studies were the focus of our mainly thematic coding. Alongside the focus on selected case studies, one member of the team undertook open coding of the entire dataset. This supporting analysis augmented our initial thematic focus by identifying relevant and representative narratives, some of which ran across a number of interviews within a case study (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008). For this paper, our analysis focuses upon the interview transcripts from the walking interviews and the network mapping (the latter being UK fieldsites only).

Findings

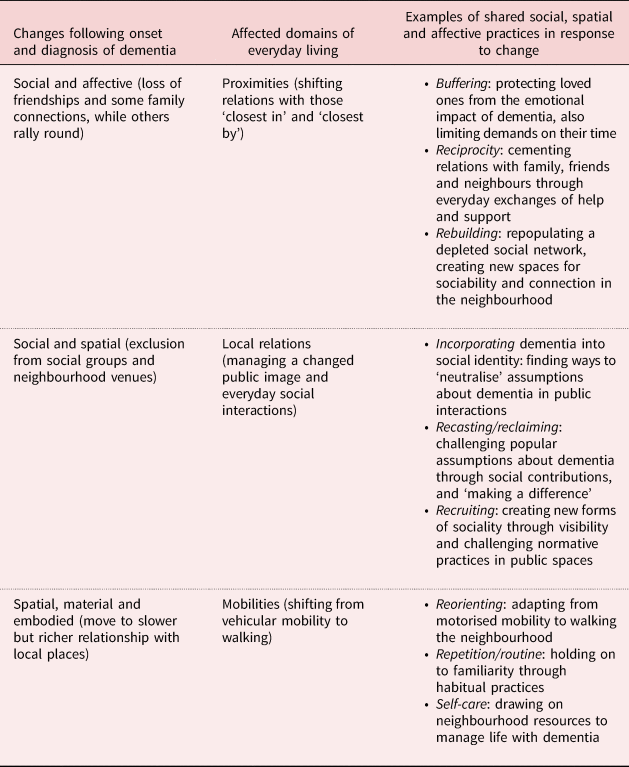

Our findings show that the onset and diagnosis of dementia commonly leads to changes across many areas of people's lives. Experiences of social exclusion were widely reported; many participants were surprised to lose friends, see less of certain family members and find themselves frozen out by neighbours. Malcolm (ScFootnote 1) noted ‘the people [on our street] we used to speak to, don't speak to [wife] now … they don't ever ask her “how are you doing Celia?”’ Experience of public, retail and service spaces also altered, some found they were ignored or talked over. Cheryl (Sc) said of Bob's general practitioner: ‘She looks past him and tells me, and I just want to remind her that's him sitting there.’ Rarely, however, were people passive in the face of such change, instead actively rebuilding social networks, challenging exclusionary practices in public spaces and making use of neighbourhood resources to manage their condition. Table 1 provides a profile of participants and methods used. Table 2 offers an overview of our findings that charts the different changes people reported and outlines examples of common responses.

Table 1. Participant profile and methods

Note: PwD: people with dementia.

Table 2. Overview of findings and themes from analysis

Our discussion of findings focuses on the affective, social and spatial practices that people adopted and adapted in managing life with dementia, widely shared by many of those we interviewed.

Proximities

While we found that social worlds often constricted, there was limited evidence to suggest this was a result of self-withdrawal. Instead, participants cited fear of dementia, poor understanding of the condition, or social awkwardness and discomfort as potential causes and revealed how these impacted on family dynamics and friendships. Experiences of avoidance and marginalising were often spatially mediated, people were no longer receiving visitors at home or being invited out with others. For instance, Betty (Sc) reflected:

We don't have anyone now that pops in, it's a strange thing. But we used to have … But since Mac became ill I just feel we don't have anyone.

Interviewees described their efforts at maintaining social networks in the face of this perceived retreat. Many were acutely aware of the impact their situation might have on those who mattered most to them and took steps to protect loved ones from day-to-day stresses of coping with dementia through buffering. For instance, Elaine (carer, GM) told us ‘I don't open up to my daughter because I don't want to unload on her. I don't think that's fair.’ Anna (GM), who lived alone, revealed she was mindful of her daughter in her efforts to remain independent:

I think it'll be good for me as long as I don't put too much thing on [daughter]. I don't want her to be … that's why I sort of get on my own horse and go round … I don't want her to be … be dependent on her all the time.

Buffering was primarily an affective practice aimed at holding back on troubles-sharing but was also temporally framed as participants self-limited demands on others’ time. Such practices revealed that participants were only too aware of their embeddedness within a wider network, where their own needs sat alongside many others.

Reciprocity in the form of everyday exchanges of help and support, such as devoting time to child care or offering emotional or practical input, was central to the give and take of neighbourhood life. It was also a means to resist assumptions about dependency or incapacity associated with dementia. Over half of our UK participants reported some level of continued involvement in child care (mainly for grandchildren), and this was often spatially and temporally organised in terms of meeting children from school, sometimes preparing meals and filling-in until parents returned from work. Olsson et al. (Reference Olsson, Lampic, Skovdahl and Engström2013) suggest that maintaining child-care responsibilities can be ‘self-affirming’ when living with dementia, it is also an important but largely overlooked form of social contribution made by people living with dementia and their care partners. Elsewhere (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark, Campbell, Graham, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Keady2018; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Campbell, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2020), we have highlighted the significance of reciprocity to neighbouring relations as integral to everyday life with dementia. Continuing to participate in small acts of often materially mediated mutual support helped to cement relations with those ‘closest by’ but also to shore up a meaningful sense of local belonging. For example, Lily (GM), who lived in an assisted housing block, told us that she would collect a newspaper for her neighbour every morning, noting that her legs were in ‘better shape’ than many of those who lived around her. Dröes et al. (Reference Dröes, Chattat, Diaz, Gove, Graff, Murphy, Verbeek, Vernooij-Dassen, Clare, Johannessen, Roes, Verhey and Charras2017), Perion and Steiner (Reference Perion and Steiner2019) and Vernooiij-Dassen et al. (Reference Vernooij-Dassen, Leatherman and Olde2011) have similarly highlighted the power of reciprocity in foregrounding the capacities of people with dementia, and the consequent importance it holds as a foundation to forging relationships.

Mapping participants’ ties to a wider web of groups and individuals revealed that while neighbourhoods may contract, they also expand as a direct result of rebuilding relationships with people and places. Many newer connections involved others affected by dementia. In this context, service providers (especially local third-sector organisations) played a crucial role in helping people living with dementia to find one another, often offering a local venue for meeting-up, thereby helping to re-establish both social and spatial neighbourhood connections. We learned that over time the giving and receipt of support could lead to friendships evolving and to the creation of new spaces of care. For instance, a number of participants (people with dementia and their care partners) belonging to a dementia network in the north-west of England made a block-booking at a seaside hotel, weaving mutual care practices into their leisure time and space.

Dementia networks were vital for exposing participants to new practices, functioning as sites for the modelling and transmission of skills and competences that enabled management of the condition and enhanced wellbeing. Ruth (Sc) had turned to digital technology as a way to repopulate her network and shared with us that she had created a ‘virtual neighbourhood’ of people with dementia around the world who took part in online meetings using teleconferencing software. She described how the necessary skills for using a tablet had been passed on to her by another member of her dementia network:

So I was sitting, and Glen got a napkin [to draw on] and he says, ‘right Ruth, that wee symbol up there is like your pad. Click on that…’ and he showed me how to tweet, and I used that napkin for ages, and through tweeting and Facebook I got to know other people with dementia and they became followers and now I have … my virtual friends are almost overtaking the [dementia network].

While the potential of technology for supporting connectedness in a dementia context is increasingly well understood (Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, PerssonVasiliou, Hwang, Mihalidis, Astelle, Sixsmith and Nygard2018; Gaber et al., Reference Gaber, Nygård, Brorsson, Kottorp and Malinowsky2019; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Dickinson, Brittain and Robinson2019), less attention has been given to the informal patterns of transmission and modelling of skills that are central to its adoption and the value of dementia networks as situations that enable this.

Local relations

Participants reported sometimes dramatic changes to their part in wider neighbourhood relations and their own perceived social standing and status. For instance, Patricia and Adam (GM) told us that difficulties on the green had led to exclusion at the golf club:

Patricia: People didn't want to play with him, you know.

Interviewer: So, people you'd played with for a long time weren't supportive?

Adam: Long time yeah … played there 18 years.

Betty (Sc) similarly shared an experience of dementia-related discrimination towards her husband at their local social club. The couple subsequently withdrew from the club, showing how social and spatial exclusion can often go hand-in-hand. Displaying signs of struggle with certain tasks can disrupt a person's ‘visible anonymity’ in public spaces (Garland-Thomson, Reference Garland-Thomson2011), drawing the gaze of others which can inhibit a person's social participation (Van Wijngaarden et al., Reference Van Wijngaarden, Alma and The2019).

The subjective challenge our participants faced involved incorporating dementia into their social identity and public self in ways that ‘neutralised’ these more negative encounters. For instance, Dennis (GM) described how he managed interactions in his local pub:

I don't launch into it at the very first moment that I meet them, but work it into a conversation and then say ‘I have dementia’ to make it not sound as though it is actually a big problem.

Susan's (GM) novel response involved dyeing her hair:

I must admit I've been known now in the town: ‘Oh, you know that lady with the purple hair’ which is preferable to ‘Oh you know that lady with dementia’.

Such actions indicate reflection on and awareness of public perceptions. Lily (GM) revealed:

I get by on crappy comedy … [My daughter] laughs with me and I have, more or less, given my family and even the people here [apartment block] the freedom to do that, because if I laugh it gives them permission to laugh, if I've done something stupid – and I do.

Humour was a mechanism to avoid judgement but also to anticipate and pre-empt the awkwardness of others. Such ongoing negotiations underline the processual and contingent nature of social identities and the effort of incorporating dementia as part of the public presentation of self.

Recasting and reclaiming dementia was a way of ‘pushing back’ at popular assumptions about the condition. Often this was done through engaging in social practices that overtly challenged public expectations of a person with dementia. Hence, a commitment to or ethos of ‘giving back’ and ‘making a difference’ were prominent in our discussions about public life. Some participants had swapped a professional identity for voluntary work or taken on a role in their local church or other neighbourhood initiative. Participating in dementia networks helped foster ‘dementia-consciousness’, where making a difference could become a more politically charged endeavour, not least through engagement with policy making, education and research. Such participation could prove transformative. For Susan (GM), campaigning and awareness-raising activities marked a new chapter:

I suppose I've grown up being told every day of my childhood ‘oh you're useless, oh you're rubbish, you'll never amount to anything’, to actually be asked to be on the committees that I'm on it's just life-giving really.

There was evidence from our walking interviews that exposure to activism through dementia networks carried over into participants’ day-to-day neighbourhood life. For instance, Susan had subsequently started to advocate independently for dementia-awareness with local businesses, and no longer tolerated impatience towards her peers:

If I'm in a café with someone who does spill their drink or something and I hear people tutting or whatever you know I'll speak up for them.

There is a growing literature on dementia activism and advocacy (e.g. Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2014; Phillipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Hall, Cridland, Fleming, Brennan-Horley, Guggisberg, Frost and Hasan2019) which demonstrates its significance not only in fighting discrimination but also in fostering solidarity between people living with dementia (Seetharaman and Chaudhury, Reference Seetharaman and Chaudhury2020). Applying a social practice lens, our research adds to this picture in highlighting the vital role of dementia networks in redefining dementia and the transmission of skills and competences as group members are recruited to new and different ways of doing. Our findings show that newly adopted practices can ‘travel’ to different domains of people's lives, enabling people to introduce changes within their neighbourhood and actively create new spaces of care and support.

Participants described how negative experiences in their neighbourhood, tied to ableist and normative assumptions, could prove exclusionary. For instance, Pam commented on her husband's experience:

…in shops … I think mostly people are very impatient and consequently by the time he's computed everything and thought of what he wants to say it's hard, you know, because they've switched off basically.

Yet, visibility as a person with dementia could disrupt such conditions. Hence, many people living with dementia were spearheading change at a local level by recruiting a range of different neighbourhood figures into adopting more inclusive practices. Linda (GM) commented on how her husband had built a relationship with their local optician:

Roger could go to the optician, have an eye test, be fitted for new glasses, and come home with something that suited him … and then they would ring me as he's setting out and they'll say he's on his way home.

Amanda (GM) and her mother Anne said of their local pub:

Amanda: There was one time wasn't there when you hadn't gone quite dressed appropriately and they'd sort of rang me, and they were so lovely, they just said, we don't want people to … you know it's about your mum's dignity and…

Anne: I don't remember that, what did I do wrong?

Amanda: It was when you were having difficulties with tights and trousers and not knowing which was which. You know how stretchy trousers can be very close to tights and so you'd gone in your tights, not trousers.

Building such connections over time helped foster social and material resources in the neighbourhood that enabled people to enjoy a degree of independence as well as a sense of attachment. These efforts at recruitment may help to understand why people living with dementia concentrate more time in certain familiar local venues and spaces.

Mobilities

Driving cessation was commonplace post-diagnosis and led to reorienting to a different relationship with the neighbourhood. The transition from car to foot brought people closer to the material environment, with mobility slowing and becoming a more ‘full-bodied’ multi-sensory experience, often increasing opportunities for sociability but also potentially bringing new risks. Perceptions of the neighbourhood altered as a result:

The distance to the shops and places, well we had a car so it didn't seem so far, but now we're having to walk it's quite a distance isn't it? (Phillipa, GM)

Such changes meant creating familiarity with the neighbourhood that was no longer mediated by motorised forms of mobility.

Building familiarity with place was rooted in repetition and routine practices, continually re-treading certain journeys, creating an embodied memory of where to go. In this way, the neighbourhood was made and re-made through everyday mobility. Elsewhere (Odzakovic et al., Reference Odzakovic, Hellstrom, Ward and Kullberg2020) we have reported how the N:OPOP study explored the significance of the daily walks taken by people with dementia in neighbourhoods in Sweden. We showed how the routine of treading a favoured route through urban or rural settings was a way of holding on to familiarity with the neighbourhood through physical engagement. For some individuals with more progressed dementia, a daily walk to buy the paper took on particular significance as an expression of independence.

We learned that familiarity was created out of routine and, for some, served to mark out the limits to their neighbourhood. Vanessa's (GM) account of an unannounced route-change on the bus underlined the spatialised nature of familiarity:

And the bus was there, there were roadworks or something so it did a detour and I didn't know where I was … but you know I was nearly having a panic attack on the bus because it wasn't the route that I'm used to going. And I was getting panicky and I couldn't breathe, but [my daughter] couldn't get where I was coming from, ‘you're alright mum you're with me’, but I said ‘this isn't the way they come’.

Vanessa's shift from comfort to distress as the bus diverts suggest that her own feelings are spatially organised and shows how a perception of the bounded nature of the neighbourhood has been created out of the repeated forms of mobility that have characterised her routine local movements. The intersection of familiarity, comfort and safety are integral to how Vanessa both defines and feels ‘local’.

The walking interviews revealed how people used their neighbourhood as a resource in practices of self-care. Green and blue spaces were especially popular when within reach, but even where participants lived in high-density inner-city areas, they still sought out signs of nature, listening for birdsong, or commenting on trees and flowers in gardens. George (Sc), who lived at the top of a large high-rise block, had filled one wall of his apartment with a mural depicting a wooded glade:

I've got a disc there and it's called ‘Echoes of Nature: Thunderstorms and Rain’ and it's great to put it on and just to start to focus on the wall and you can take yourself out of here. It's slightly Alice in Wonderland syndrome.

His use of imagination to transcend his spatial and material conditions highlights how the practices people employ to engage with their environment are crucial to their wellbeing and management of the condition.

Natural spaces also facilitated a particular way of being and of moving around. Strolling through green and open spaces provided interactional scaffolding that emphasised in situ observation over memory and recall. Gayle (carer, Sc) recalled:

So we used to come up here and do, you know, like a ‘show me – tell me walk’ … we used to talk about what kind of flowers there were and what kinds of birds were they because he's quite interested in birds, believe it or not.

We witnessed first-hand how the rich sensory experience of the natural environment facilitated interaction as walks progressed.

For other interviewees, the neighbourhood was socially defined, and our walks were punctuated with short vignettes about friends and neighbours. Judy (Sc) paused, shortly after leaving her house:

Oh Beryl lives there, I usually look to see if she's in and wave. Sometimes I go in because … hello (waves). She's not been too well she's had a couple of bad fractures but she's out walking again now a bit.

For Judy, walking was a mode of social participation, a way of being party to the local ‘place-event’ of the neighbourhood. We witnessed this many times with participants as they engaged in a series of fleeting encounters with friendly faces and passers-by. Indeed, a revealing aspect to the walks was the sense of connection to emerge cumulatively from repeated brief exchanges, nods, smiles and waves of hello. As Dennis (GM) reflected:

It might only last 20 seconds but you've spoke to someone that you've never met before and they're quite happy just to say ‘good morning lovely day’, and I love doing that down there on the canal because that's the main place it happens to me.

The familiar local landscape was widely exploited for opportunistic forms of sociability. Kate and her husband Percy (GM) shared with us:

Kate: I sit on the drive.

Percy: Uhuh. She sits on the drive a lot … and children go up.

Kate: There's one who lives opposite and he brings all the school kids with him … I enjoy it, I enjoy children talking.

Anna (Sw), who lived alone, headed to a local bench in the hope of social interaction:

This summer was too long, then it [seating area in neighbourhood] almost becomes a small meeting point for pensioners. It's our pleasure, we count cars here. I can sit here for a while and sometimes there's nobody to talk to, sometimes there is someone that I can talk with.

Kate and Anna's strategic positioning show that social and spatial practices overlap in their efforts to engage with their neighbourhood. While the reach of people's movement may have altered, a transition to walking (and sitting) had enriched the relationship with their social and physical environment.

Discussion

A clearer understanding of shared practices associated with living with dementia in a neighbourhood context, and how these are transmitted and adopted over time, is potentially valuable to the development of policy and practice. It can inform the delivery of services, helping to organise and focus the work of community practitioners, and may prove useful to those newly diagnosed. The findings show that the onset and diagnosis of dementia is marked by sometimes dramatic social change that includes widely shared experiences of exclusion and marginalising (Van Wijngaarden et al., Reference Van Wijngaarden, Alma and The2019) but which also triggers the mobilising of different kinds of support (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Philip and Komesaroff2019). We found social networks to be fluid and responsive but not necessarily predictable or reliable. Using mapping to examine the give and take of support, many participants revealed depletion to their networks following diagnosis, often hand-in-hand with exclusion from neighbourhood venues and spaces, but outlined their efforts at rebuilding and repopulating, highlighting that while social worlds may well contract, they can also expand. This finding challenges narratives of irreversible decline and apparent withdrawal linked to progressive impairment (Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008; Shoval et al., Reference Shoval, Wahl, Auslander, Isaacson, Oswald, Edry, Landau and Heinik2011).

We also found that abandonment of certain mobility practices, especially driving, led to reconfiguring relationships with place. People with dementia often adopt and/or are recruited to new spatial practices, where speed and reach are exchanged for a richer, multi-sensory engagement with the material neighbourhood, opening up new and opportunistic forms of sociability, and supporting people to engage with ordinary spaces in beneficial ways (Phillips and Evans, Reference Phillips and Evans2018). A narrow focus, within much existing research, on the geographies and scale of the day-to-day movement of people with dementia has failed to engage with the richness of this relationship to diverse places, or the active negotiations with people and places that are a marker of a person's attachment and commitment to being part of their neighbourhood.

We have drawn together a social-relational understanding of neighbourhood (Massey, Reference Massey2005; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Evans and Wiles2013) with attention to the embodied-material aspects of people's experience of place (Pink, Reference Pink2012). A relational lens emphasises fluidity and the changing nature of place over representations that assume stability and structure (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Campbell, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2020), where variation and unpredictability can exist as a constant threat (Tucker, Reference Tucker2010). This might help to explain the significance for so many of our participants of holding on to familiarity, embodying as it does a sense of continuity and normalcy which ultimately helps to make the world a more comfortable place (Dröes et al., Reference Dröes, Chattat, Diaz, Gove, Graff, Murphy, Verbeek, Vernooij-Dassen, Clare, Johannessen, Roes, Verhey and Charras2017). This insight suggests that while neighbourhoods may be experienced in diverse ways, as both contingent and unfolding, collective participation in a nexus of social and spatial practices can carry shared meanings of place (Pink, Reference Pink2012). For many of the people we interviewed, the intersection of familiarity, comfort and safety helped to define ‘local’ and drove participation in certain habitual, repeated practices (Brorsson et al., Reference Brorsson, Ohman, Lundberg, Cutchin and Nygard2020; Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Burton, Leverton, Herat-Gunaratne, Beresford-Dent, Lord, Downs, Boex, Horsley, Giebel and Cooper2020). However, it is important to recognise this is by no means universally the case, Clarke and Bailey (Reference Clarke and Bailey2016), for instance, have highlighted occasions where familiarity may lead to a sense of estrangement as a person recognises their struggle to continue certain practices, reinforcing awareness of their limitations (see also Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Lampic, Skovdahl and Engström2013; Bartlett and Brannelly, Reference Bartlett and Brannelly2019). As such, we are not arguing that familiarity constitutes a defining feature or property of neighbourhoods, rather it is a meaning shared and enacted by many people living with dementia. In a context of flux and instability, familiarity can also be understood as an achievement (Pink, Reference Pink2012), an object or product of everyday social and spatial practices, akin to what Tucker (Reference Tucker2010) describes as an anchor point.

We found that a person's day-to-day experience fluctuates between the familiar and unfamiliar, comfort and discomfort, and from safety to risk as people with dementia move place-to-place. This shifting relationship underlines the effortful nature of public life with dementia and opens to question any suggestion that public spaces can be ‘fixed’ or engineered to generate knowable or stable outcomes for certain inhabitants. Massey (Reference Massey2005), who draws upon non-representational theory, argues we need to disentangle the experience of place from its representation. Thus, reporting on research into rural experiences of dementia, Blackstock et al. (Reference Blackstock, Innes, Cox, Smith and Mason2006) caution against binary thinking associated with rural–urban contrasts and highlight the pitfall of romanticising rural life, pointing instead to a diverse and nuanced set of experiences. Similarly, within environmental gerontology, Phillips et al. (Reference Phillips, Walford, Hockey, Foreman and Lewis2013: 114) have argued that far too much emphasis has been placed upon ‘locational domains’ rather than seeking to understand ‘the complexity of how older people experience space and place in the built environment’. In other words, generic signifiers of place such as ‘neighbourhood’ (and we might add ‘dementia-friendly communities’) may serve to obfuscate our understanding of life with dementia rather than enhance it. We argue this points to the significance, for research, policy and practice, of foregrounding the ‘lived neighbourhood’ (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark, Campbell, Graham, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Keady2018; Odzakovic et al., Reference Odzakovic, Kullberg, Hellström, Clark, Campbell, Manji, Rummery, Keady and Ward2021) and the benefits of attending to the social and spatial practices by which a person engages with and derives meaning from their neighbourhood.

A potential limitation of this study is that we recruited a proportion of participants in both UK fieldsites from networks led by people living with dementia. We may then have over-represented participation in such groups and disproportionately emphasised a commitment to activism, advocacy and the desire to ‘make a difference’. Nonetheless, viewed through a social practice lens, these networks can be understood as vital fora for exposure to and the transmission of new and different ways of doing. Participants described how dementia networks challenged and redefined medicalised models of dementia (meaning), introduced them to new tools and technology (materials), while inducting new members by sharing skills and modelling approaches (competences) that enabled them to better manage life with dementia. Membership also opened doors to further networks (policy, practice and academic) and enabled the creation of new neighbourhood spaces and forms of sociality. Maller (Reference Maller2015) has argued that a shift in focus for health policy and practice from the individual to communities of practice such as these, might help to better understand and influence social change concerning health and wellbeing. Yet historically, dementia policy and practice has tended to overlook the contribution of secondary and tertiary sources of support and wider networks, focusing narrowly on care dyads (Dam et al., Reference Dam, Boots, Van Boxtel, Verhey and De Vugt2018; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Philip and Komesaroff2019). Our research raises the question of whether it is time to progress from ‘person-centred’ care and instead consider the potential of ‘neighbourhood-centred’ practice as a framework for the provision of support. Not only do people living with dementia belong to a web of relations and wider networks that are vital to how they manage life with the condition, but those relations are emplaced and shifting over time.

Conclusion

The focus here on social practices is not intended to deny impairment effects or gloss over the experience of dependency associated with progression of dementia. Our aim has been to problematise a dominant narrative of decline that fails to take into account a broader experience of living with dementia or to acknowledge the meanings, materials and competencies that people engage with as they adapt to life with the condition. Earlier research has adhered to a deficit model of dementia as an explanatory framework, inadequately accounting for the outcomes of the agentive practices of individuals living with the condition and of their participation in emerging communities of practice. As such, the notion of a shrinking world offers a partial and unhelpfully negative picture of neighbourhood life that reinforces ideas of the passivity of people with dementia. Indeed, the logical endpoint of a steadily shrinking world is absolute immobility and isolation. By contrast, our research shows that people with dementia and those who care for and support them ‘push back’ by taking steps to rebuild their worlds; fostering new friendships, engaging in opportunistic sociability and endeavouring to keep places of importance reachable and accessible. Yet, this everyday struggle is barely alleviated through formal support and services. A more actively co-ordinated political drive to support the agency of people with dementia is needed, one that strengthens networks and provides the necessary platform and resources to speed the process of building enabling neighbourhoods.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants who generously gave their time and expertise to support the study; Dr Grant Gibson for his review of an earlier draft of this paper; Barbara Graham and Kirsty Alexander, who worked on the study as researchers; and the two anonymous reviewers.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC; part of UK Research and Innovation); and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the ESRC or the NIHR. This work formed part of the ESRC/NIHR Neighbourhoods and Dementia mixed-methods study (https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/neighbourhoods-and-dementia/) and is taken from work programmes 4.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the NHS Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee (record reference 15/IEC08/0007) and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (the county of Östergötland, Sweden) (record reference 2013/200-31 and 2014/359-32) as well as relevant institutional approval.