Background

Sexual violence against women is commonly accepted in many sub-Saharan African countries despite the international commitment to halt it (WHO, 2013). This is partly due to sociocultural norms about gender roles (Bamiwuye & Odimegwu, Reference Bamiwuye and Odimegwu2014). Sexual violence is defined as “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed against a person’s sexuality, using coercion, by any person, regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including, but not limited to, home and work” (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg and Zwi2002). Instances of sexual violence include rape within marriage, unwelcome sexual advances or harassment, and sexual abuse of people with physical or mental disabilities (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg and Zwi2002). It has several adverse health implications (Bott et al., Reference Bott, Guedes, Goodwin and Mendoza2012) including injuries, increased susceptibility to unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections including HIV and AIDS (Campbell, Reference Campbell2002; WHO, 2013), and lower antenatal care uptake (Tura & Licoze, Reference Tura and Licoze2019). Besides, sexual violence has enormous adverse implications for women’s emotional well-being and mental health (Tarzia et al., Reference Tarzia, Thuraisingam and Novy2018; Temple et al., Reference Temple, Weston, Rodriguez and Marshall2007; Weindl et al., Reference Weindl, Knefel, Glu and Lueger-Schuster2020). More women in Africa are subjected to lifetime sexual assault (11.9%) than women in other parts of the world (García-Moreno et al., Reference García-Moreno, Pallitto, Devries, Stöckl, Watts and Abrahams2013).

Acceptance of violence is common among women with no or low education and those with poor decision-making capacity in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Dickson and Seidu2018; McCloskey, Reference McCloskey2016). Culture and traditions motivated by patriarchal beliefs also fuel women’s acceptance of sexual violence (McCloskey, Reference McCloskey2016). Unfortunately, patriarchal privilege appears dominant globally, manifested in the widespread of men’s dominance over women (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Dunkle, Ramsoomar, Willan, Shai, Chatterji and Jewkes2020a). Poverty and limited access to resources and employment opportunities further curtail women’s decision-making capacity and aligns them to victimisation (Cools & Kotsadam, Reference Cools and Kotsadam2017; Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Dunkle, Ramsoomar, Willan, Jama Shai, Chatterji and Jewkes2020b; Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Abdelatif, Washington, Chirwa, Willan, Shai and Jewkes2020c). The justification that violence is an acceptable cultural norm is among the most significant factors associated with the likelihood of perpetration and society’s reaction to the conduct (Chirwa et al., Reference Chirwa, Sikweyiya, Addo-Lartey, Ogum Alangea, Coker-Appiah, Adanu and Jewkes2018). Women who hold the belief that violence is an acceptable social norm are more likely to blame themselves for the violence, experience long-term mental health problems, and less likely to report the problem to civil authorities or other family members (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018).

The justification of violence by people other than the perpetrator or victim shapes responses to the violence. This is because people who regard violence as a cultural norm tend to have a more positive attitude towards the action and have less empathy and support for victims (Pavlou & Knowles, Reference Pavlou and Knowles2001; West & Wandrei, Reference West and Wandrei2002). Attitudes to and beliefs about intimate partner violence (IPV) are, therefore, associated not only with its prevalence but also with how community members respond to the act (Tran et al., Reference Tran, Nguyen and Fisher2016). Attitudes about violence perpetrated against women are determined by multiple factors, with social norms and beliefs about traditional gender roles influencing attitudes towards IPV and these transmit from generation to generation (Flood & Pease, Reference Flood and Pease2009).

Previous studies from some sub-Saharan African countries such as Ghana and Ethiopia have demonstrated that women who can take the sole decision on their healthcare and other critical decisions have a lower inclination to wife beating acceptance (Ebrahim & Atteraya, Reference Ebrahim and Atteraya2018), higher chances of maternal healthcare utilisation (Ameyaw et al., Reference Ameyaw, Tanle, Kissah-Korsah and Amo-Adjei2016), and high contraceptive use (Ameyaw et al., Reference Ameyaw, Kofinti and Appiah2017). Meanwhile, one study investigating women’s decision-making capacity across eighteen sub-Saharan African countries noted that women who were having decision-making capacity were more likely to experience intimate partner violence (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Dickson and Seidu2018). Although counter-intuitive, the explanation the authors gave was that more empowered women might oppose some behaviours and decisions from their partners that can affect them negatively. With this, the men might think they are being challenged by their partners, which could lead to confrontations. This high tendency for empowered women to be violated, referred to as ‘backlash’, occurs in high-income countries as well (Ericsson, Reference Ericsson2020) and suggest that both empowered and non-empowered women stand a chance of being sexually violated. This study seeks to add to the already existing literature on decision-making capacity and sexual violence in SSA by examining the relationship between healthcare decision-making capacity and justification of sexual violence in SSA, using nationally representative datasets.

Theoretical framework

There are so many theories designed to explain, predict, and better understand the cause of violence acceptance. The resource theory and the subculture-of-violence theory were used to explain healthcare decision-making capacity and justification of sexual violence (Straus, Reference Straus1979). Resource theory designates that the availability of resources to both men and women determines the nature and magnitude of violence among partners, especially when seeking healthcare and probably justification of sexual violence. Some researchers (e.g., Goode, Reference Goode1971; Straus,Reference Straus1979) have argued that the imbalance in decision-making capacity and justification of sexual violence among income groups occurs because individuals with lower socio-economic status (i.e., income and social status) may have fewer legitimate resources to utilize to attain power. Some proponents of the resource theory have suggested that the availability of resources for women may, to some extent, alter the dependency relationship between men and women, and possibly lower men’s dominance over women in the domestic space. Applying the resource theory to men’s justification of sexual violence against women, we can argue that women’s financial independence and autonomy provide some form of protection against physical violence. The lack of such resources may not only make women vulnerable to decision-making capacity, but also the justification of sexual violence. Thus, lower levels of socio-economic status (i.e., income, education and occupation) may predispose men to accept violence against women, especially in times when they solely decide between seeking healthcare, ownership of property, and purchases of domestic basic needs. The subculture-of-violence theory developed by Wolfgang and Ferracuti (Reference Wolfgang, Ferracuti and Mannheim1967) posits that the occurrence of sexual violence is not evenly distributed among groups in the social structure; it is concentrated in poor urban areas. According to these theorists, since violence is known to occur frequently among a specific subset of the larger community, it is believed that there is a value system at work in that subculture that makes violence more likely. According to Wolfgang and Ferracuti (Reference Wolfgang, Ferracuti and Mannheim1967), “there is a potent theme of sexual violence present in the cluster of values that make up the lifestyle, the socialization process, the interpersonal relationships of individuals living in similar conditions” (p. 140). This suggests that individuals found in that sub-culture learn the values and norms of sexual violence through socialization in their immediate households either by observing their parents treat each other or how neighbours control each other. In other words, violence is learned socially and passed on by group members, thus sustaining the subculture of violence. In applying the subculture-of-violence theory to this study, we hypothesized that decision-making and justification of sexual violence measured by the sociodemographic characteristics relate to justification of sexual violence, particularly against women in unions.

Methods

Data source

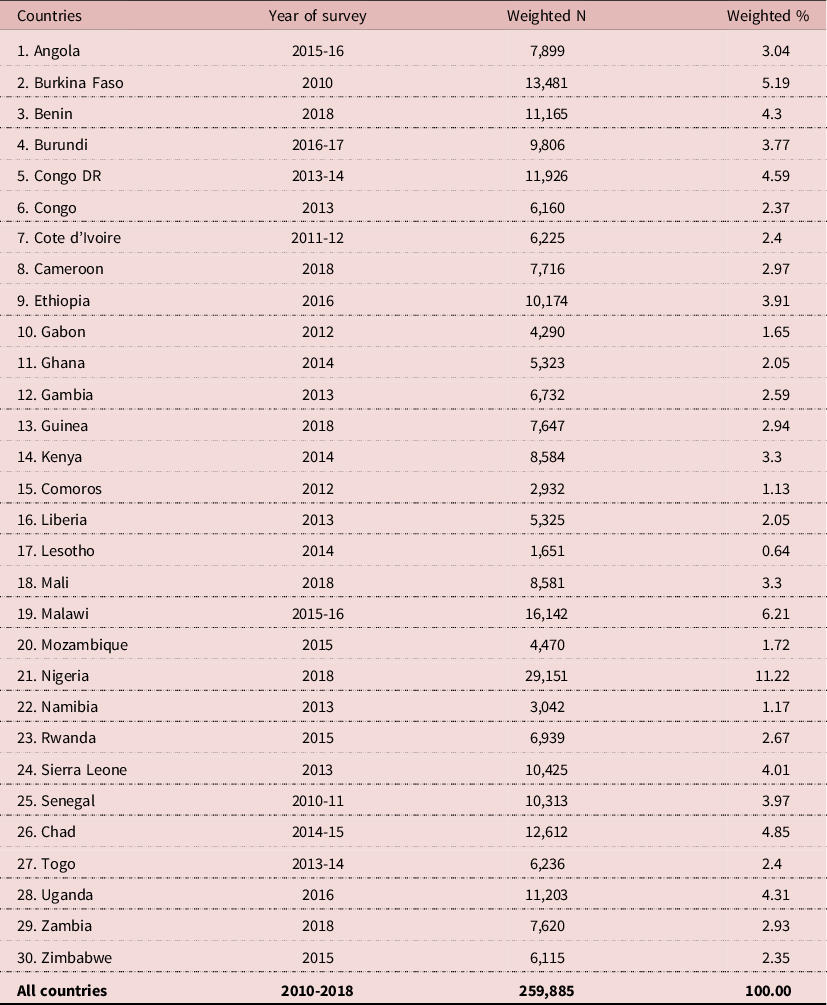

The study used pooled data from current Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted from 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2018, in 30 countries in SSA (see Figure 1). The DHS Program aims at monitoring health indicators in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). The survey captures a wide range of information on sexual and domestic violence as well as maternal and child health issues. The survey is representative of each of these countries. Files for women in sexual unions were used for our study and these files possess the responses from women aged 15 to 49 years. The DHS survey employed a stratified two-stage sampling technique to ensure national representativeness. The sample included 259,885 women who were in sexual unions. Table 1 shows the sample distribution across the countries considered in this study.

Figure 1. Justification of sexual violence among women in SSA.

Table 1. Description of the study sample

Definition of variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable for the study was justification of sexual violence. This was derived from the question where women were asked whether beating is justified if a wife refuses sex from her partner. Responses were “Yes”, “No” and “Don’t Know”. These were coded as “No” =0, “Yes=1” and “Don’t Know=8”. For the analysis, only women who provided confirmatory responses (either “Yes” or “No”) were included in the study and this translated into a sample of 259,885 women in unions. To provide a binary outcome, the two responses were coded as follows: “No=0” and “Yes=1”.

Explanatory variable

Women’s healthcare decision-making capacity constituted the principal explanatory variable for the study. To obtain this variable, women were asked “who usually decides on respondent’s healthcare” with five responses. These were “respondent alone”, “respondent and husband/partner”, “husband/partner alone”, “someone else”, and “other”. We recoded these responses to get a dummy outcome with all women who indicated that they decide on their healthcare alone coded as “Alone=1” whilst all other responses were coded as “Not alone=0” (Osamor & Grady, 2018). Apart from the key explanatory variable, other variables, grouped into individual and contextual level variables were included as covariates. The individual-level variables were age, marital status, religion, and occupation. The contextual level variables were wealth quintile, sex of household head, and residence. These variables were chosen due to their significant association with the justification of sexual violence (Chibber et al., 2012; Puri et al., 2012). Two of these variables were recoded to make them meaningful for analysis and interpretation. Occupation was captured as ‘not working (0)’, ‘managerial (1)’, ‘clerical (2)’, ‘sales (3)’, ‘agricultural (4)’, ‘household (5)’, ‘services (6)’, ‘manual (7)’ and “Other (8)”. We recoded religion as ‘Christianity (1)’, ‘Islam (2)’, and ‘other religion (3)’.

Analyses

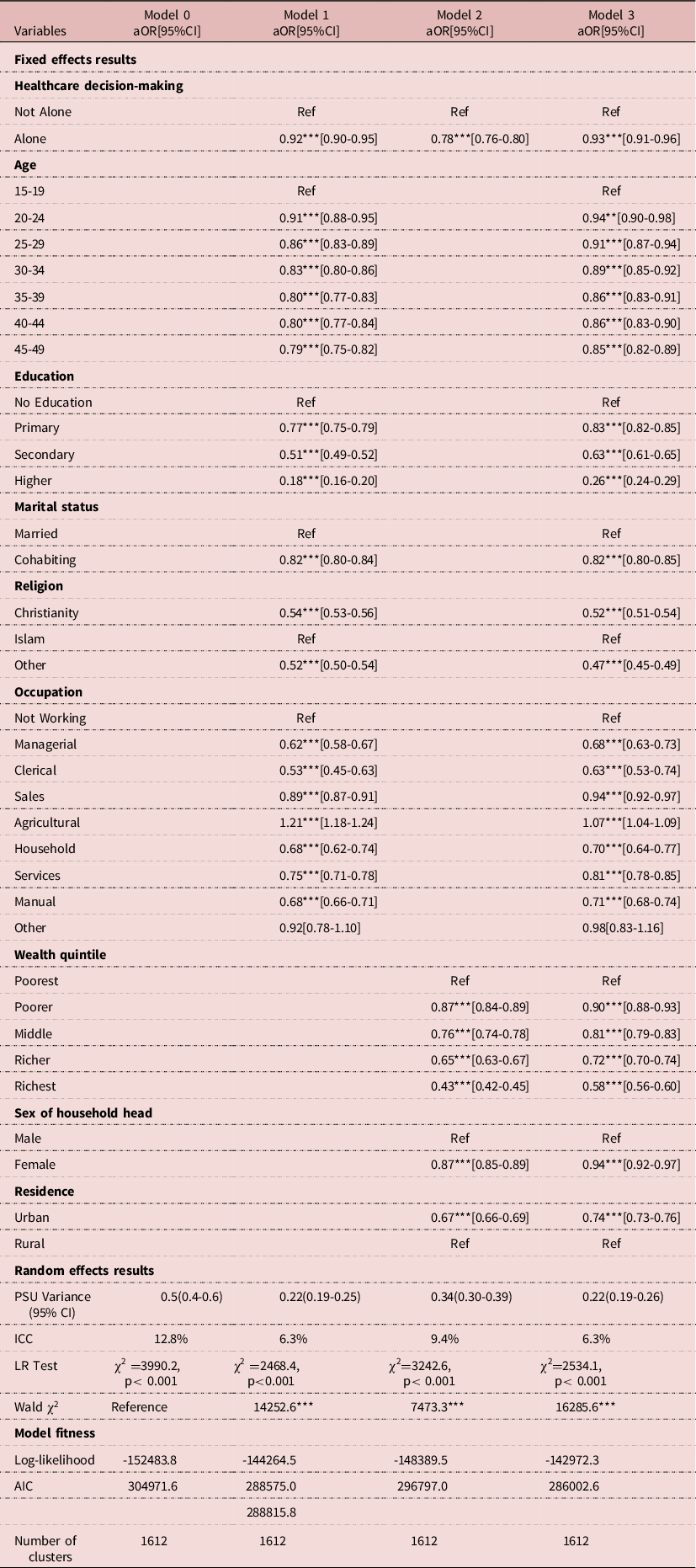

The data were analysed using Stata version 13. Our analysis began with the computation of the justification of sexual violence among women in SSA. Afterwards, a descriptive investigation into the socio-demographic characteristics was presented. We then conducted a chi-square test to ascertain the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and justification of sexual violence. This was done to identify significant variables to be considered for the inferential analysis. All of these were reported in Table 2. At the inferential level, a two level multilevel binary logistic regression analysis was done to assess the individual and level factors associated with the justification of sexual violence. In this study, women were nested within clusters. Clusters were considered as a random effect to account for the unexplained variability at the household and community level (Solanke et al., Reference Solanke, Oyinlola, Oyeleye and Ilesanmi2019). Multicollinearity was tested using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The multicollinearity test revealed no high collinearity among the variables (mean VIF=1.21; maximum=1.57; minimum=1.03). Four models were fitted (see Table 3). Firstly, model 1 was an empty model that was fitted and had no predictors (random intercept). Afterwards, model II contained the key explanatory variable and the individual level variables, model III contained the key explanatory variable and contextual level variables, and model IV contained the key explanatory variable and the individual level and contextual level variables. For all models, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented. For model comparison, the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) and Akaike information criteria (AIC) tests were used. Sample weight (v005/1,000,000) was applied in all the analyses to correct for over- and under-sampling while the SVY command was used to account for the complex survey design and generalizability of the findings. Results for the fixed effect analysis were presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with their respective confidence intervals at a 5% margin of error.

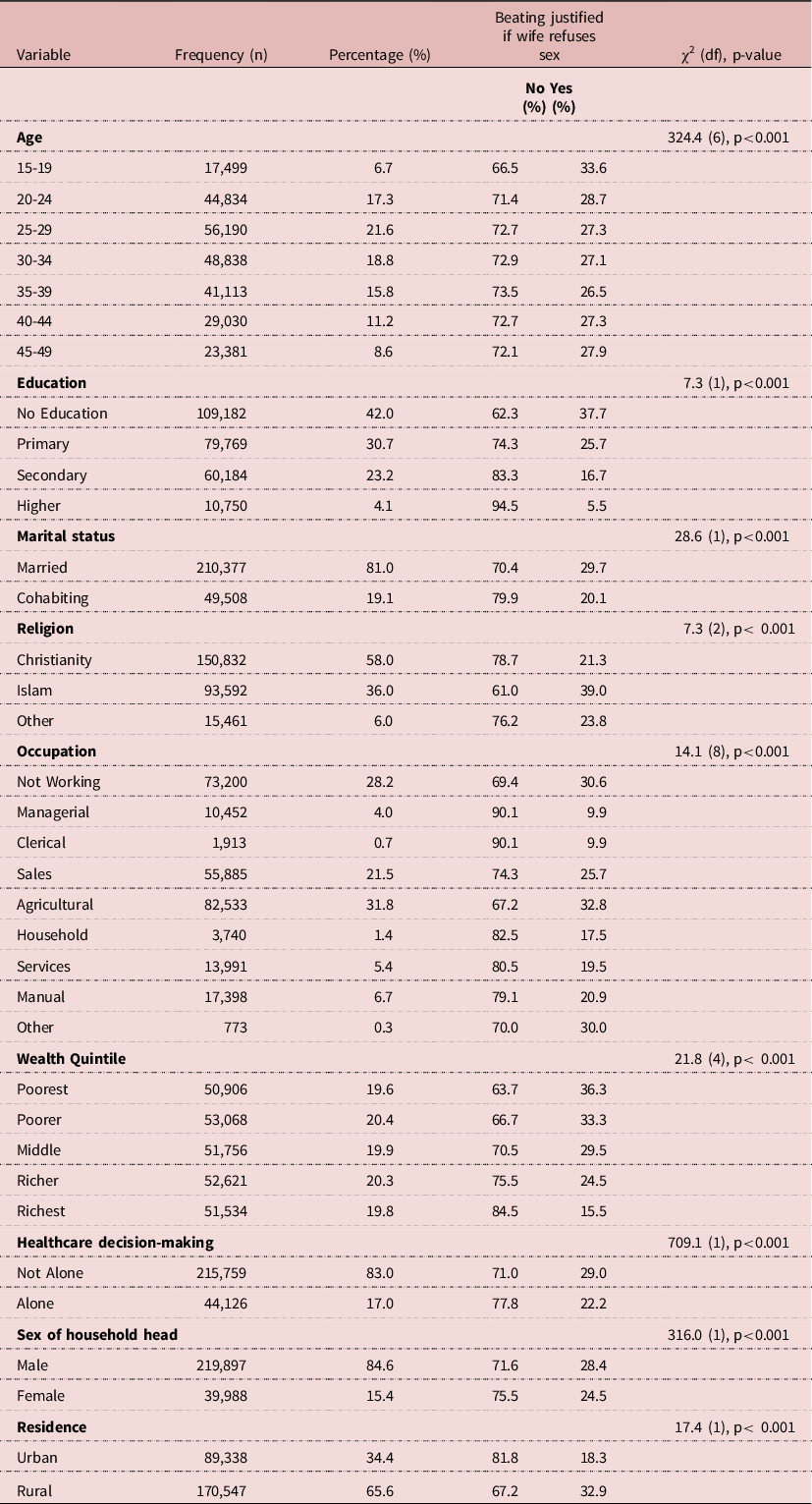

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics and justification of sexual violence Among Women in SSA (n=259,885)

Source: Demographic and Health Survey, χ2= Chi-square, df=degree of freedom.

Table 3. Multilevel logistic regression models on healthcare decision-making and justification of sexual violence

Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals in brackets; AOR adjusted Odds Ratios CI Confidence Interval

*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

PSU=Primary Sampling Unit; ICC = Intra-Class Correlation; LR Test= Likelihood ratio Test; AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion; BIC = Schwarz’s Bayesian Information Criteria.

Ethical approval

Since the data were not collected by the authors of this paper, permission was sought from the MEASURE DHS website and access to the data was provided after our intention for the request was assessed and approved on 27th December 2019. The data can be accessed from their website (www.measuredhs.com).

Results

Justification of sexual violence among women in SSA

Figure 1 presents the results on the justification of sexual violence among women in SSA. It was found that 27.8% of women in SSA indicated that it is justified for a wife to be beaten when she refuses sex. This ranged from 5.7% in Mozambique to 66.3% in Mali.

Socio-demographic characteristics and justification of sexual violence among women in SSA

Table 2 presents results on socio-demographic characteristics and the prevalence of justification of sexual violence. Whilst 21.6% of the women were aged 25-29, 6.7% were aged 15-19. Women with no formal education constituted 42.0% whereas 4.1% had a tertiary level of education. A greater percentage (81.0%) of the women were married. It was realised that 58.0% were Christians while 6.0% belonged to ‘other’ religions. Poorer women made up 20.4% whilst 31.8% were engaged in agriculture. A greater proportion of the women (65.6%) were residing in rural areas, and 34.4% were residents of urban areas. Results from the chi-square test showed that all the socio-demographic characteristics have a statistically significant association with a justification of sexual violence.

Healthcare decision-making and justification of sexual violence among women in SSA

Table 3 reports the findings of the multi-level binary logistic regression analysis (fixed effects analysis). As indicated in Model 3, women who decided on their healthcare were 7% less likely to justify violence compared to those who were not deciding alone [AOR=0.93, CI=0.91-0.96]. The results also showed that women aged 45-49 [AOR=0.85; CI=0.82-0.89] had lower odds of indicating that it is justified for a wife to be beaten if she refuses to have sex with her partner compared to those aged 15-19. With education, those with higher education [AOR=0.26; CI=0.24-0.29] had lower odds of accepting wife beating if a woman refuses to have sex with her partner compared to women who do not have formal education. Cohabiting women (AOR=0.82, CI=0.80-0.85] also had lower odds of justifying sexual violence. Compared to those who professed the Islamic faith, Christians had lower odds [AOR=0.52; CI=0.51-0.54] of justifying sexual violence. Women who engaged in agriculture had higher odds of justifying sexual violence compared with those who were not working [AOR=1.07; CI=1.04-1.09]. The richest women [AOR= 0.58; CI=0.56-0.60] had lower odds of justifying sexual violence compared to those in the poorest wealth quintile. Those in female-headed households had lower odds of justifying sexual violence compared with those in male-headed households. Women living in urban areas [AOR=0.74; CI=0.73-0.76] had lower odds of justifying wife beating if a woman refuses to have sex with her partner compared to women in urban areas. The finding from the random effect is also presented in Table 3. From the empty or first model, there is a significant contextual variation in the justification. The intraclass correlation (ICC) revealed that 12.8% variation in the justification of sexual violence is attributable to contextual factors whilst 6.3% variation is attributable to both individual and contextual level factors.

Discussion

Over the years, high incidences of sexual violence have been reported in the SSA region (Kilonzo et al., Reference Kilonzo, Ndung’u, Nthamburi, Ajema, Taegtmeyer, Theobald and Tolhurst2009; Population Council, 2014; Cool & Kotsadam, Reference Cools and Kotsadam2017). The WHO has expressed the need for investigation into the interaction between decision-making and intimate partner violence (World Health Organization, 2013). The current study, therefore, investigated the interaction between women’s health decision-making capacity and the justification of sexual violence in SSA. We noticed that women who decided on their healthcare alone had lower odds of justifying sexual violence. This finding affirms the proposition of the resource theory (Allen & Straus, Reference Straus1979). It has been documented that the ability of women to decide on critical issues such as their healthcare reduces their chances of accepting or justifying all forms of violence (Ebrahim & Atteraya, Reference Ebrahim and Atteraya2018). A plethora of evidence has also indicated that women who participate in decision-making are unlikely to support violence of any kind (Sripad, Warren, Hindin & Karra, Reference Sripad, Warren, Hindin and Karra2019; Scott, Reference Scott2015). Women’s ability to decide on essential issues that affect their well-being has been noted as a key determinant of their autonomy or empowerment status (Hunt & Samman, Reference Hunt and Samman2016).

Women aged 30-34 years had lower odds of indicating that it is justified for a wife to be beaten if she refuses to have sex with her partner compared to those aged 15-19. This corroborates the findings of previous studies in Ghana (Dickson, Ameyaw, & Darteh, Reference Dickson, Ameyaw and Darteh2020; Doku & Asante, Reference Doku and Asante2015) which showed that young women are more likely to justify wife beating. Scott (Reference Scott2015) and García-Moreno et al. (Reference García-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2005) also recount that women of lower age are more susceptible to being victims, perpetrators, or advocates of sexual violence.

Those living in urban areas had lower odds of accepting sexual violence if a woman refuses to have sex with her partner. Rural residents tend to receive limited comprehensive education on violence compared with urban residents (Jakubec et al., Reference Jakubec, Carter-Snell, Ofrim and Skanderup2013). It is known that the perpetration and acceptance of sexual violence have cultural dimensions (McCloskey, Reference McCloskey2016). To a greater extent, culturally engrained practices, such as sexual violence, are less pronounced in urban locations compared to rural settings (Tani, Hashimoto, & Ochiai, Reference Tani, Hashimoto and Ochiai2016; UNESCO, 2019). Laws against sexual violence seem to exist in most SSA countries; however, due to relatively easy access to the internet, electricity, and electronic and print media in urban locations, urban residents may be more conversant about the implications of sexual violence than residents of rural areas (Sahn & Stifel, Reference Sahn and Stifel2003). The observed variation indicates that possible contextual norms governing women’s perception of sexual violence diverge by place of residence (Sripad et al., Reference Sripad, Warren, Hindin and Karra2019). To reverse this narrative, there is a need to systematically implement anti-sexual violence structures and provide resources to improve the situation in rural settings. For instance, increasing police personnel and unravelling secret locations where sexual violence can occur covertly may be worthwhile (García-Moreno et al., Reference García-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2005).

We noticed that women with higher education had lower odds of accepting wife beating if she refuses to have sex with her partner. Education is a major tool for combating the perpetration and justification of all forms of sexual violence (McCloskey, Reference McCloskey2016). This is because educated women do have more access and are more likely to have a better appreciation of efforts to end sexual violence (Scott, Reference Scott2015). Education enlightens women on barbaric practices such as sexual violence and female genital cutting/mutilation and strengthens women to oppose all these acts and embrace actions that reinforce human rights and equity between males and females (Sripad et al., Reference Sripad, Warren, Hindin and Karra2019).

The richest women had lower odds of justifying sexual violence. To be rich, as a woman, is one of the approaches to empowerment and autonomy (Hunt & Samman, Reference Hunt and Samman2016). Due to this, a rich woman may even be the breadwinner of her household. In that case, it might be difficult for her to compromise on any form of sexual violence. This is in line with the resource theory that a woman’s resource, wealth in this context, predicts her reaction to inhuman acts such as sexual violence (Allen & Straus, Reference Straus1979). The richest women are likely to exercise at least their fundamental human rights, negotiate for sex, and welcome sexual advances that are devoid of cohesion (Donald et al., Reference Donald, Koolwal, Annan, Falb and Goldstein2017). Meanwhile, it is worth noting that in the face of culture, social norms, and patriarchy, some rich women may accept sexual violence as wealth does not necessarily insulate rich women from the aforementioned contextual factors. The situation of poor women may be different, considering that most poor women usually depend solely on their partners for their upkeep and other needs (Stuart, Gény, & Abdulkadri, Reference Stuart, Gény and Abdulkadri2018). More often than not, poor women mostly tend to be at the beck and call of their partners and are more likely to be swayed into justifying sexual violence in order not to lose their sources of livelihood (Oyediran & Odusola, Reference Oyediran and Odusola2004; Stuart, Gény & Abdulkadri, Reference Stuart, Gény and Abdulkadri2018).

Women who engaged in agriculture had higher odds of justifying sexual violence. In most SSA countries, women in agriculture are less endowed farmers using primitive agricultural methods (Moyo, Reference Moyo2016). These women, therefore, might possess limited bargaining power within the household (Stuart, Gény & Abdulkadri, Reference Stuart, Gény and Abdulkadri2018). This situation may make them susceptible to experiencing and justifying all forms of violence even in advanced countries outside the SSA region (Center for Southern Poverty Law, 2008; Human Rights Watch, 2011; Kominers, Reference Kominers2015). The poverty situation conceivably makes these women dependent on their partners/husbands who are usually the perpetrators of the act (Patel, Reference Patel2016).

It was observed that Christians had lower odds of justifying sexual violence relative to Islamic women. One striking difference between the various religions is the variation in beliefs (Herstad, Reference Herstad2009). The Christian religion is noted to play some critical roles to halt the perpetration of sexual violence as evident in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Liberia (Roux, Reference Roux2014). Ushe (Reference Ushe2015) also notes that Islam and other religions can serve as conduits for teaching the public to desist from sexual violence. He opined that Islamic teachings should be delivered in a manner that will substantially enhance unity, equality, and cordial relationship between men and women. In furtherance to Ushe (Reference Ushe2015) position, our finding could be an affirmation that indeed women in Islamic communities have increased prospects of subordination and violation as reported by other scholars (Kamaruddin & Oseni, Reference Kamaruddin and Oseni2013; Ridwan & Susanti, Reference Ridwan and Susanti2019).

Women who were cohabiting and those in female-headed households had lower odds of justifying sexual violence. This may suggest that being independent or the leader of a household could subside the likelihood of sexual violence acceptance in SSA. The finding reinforces the fundamental argument of the resource theory that the autonomy and resources available to one’s disposal influence the person’s disposition toward acts like sexual violence (Allen & Straus,Reference Straus1979). Women who are cohabiting are plausible to exercise much independence and control over their lives and choices. This is because their bride prices are not paid and hence, they have the liberty to live the life they prefer and exercise their rights freely; and hence, being less probable to justify sexual violence. Similarly, female household heads could empower other women in their households to uphold their fundamental human rights and resist the violence of all forms (Beegle & Walle, Reference Beegle and Walle2019). Supposedly, empowering women to take up leadership roles in households can fast-track efforts to end sexual abuse in SSA.

The findings illustrate the contextual environment of women cannot be downplayed in mitigating sexual violence in SSA. This highlights the essence for governments of SSA countries and sexual anti-violence organisations to understudy contextual variations concerning drivers of sexual violence acceptance in SSA. It is worth mentioning that an approach that may fit a particular context may regress the situation in another context even within the same country. Focusing on the contextual variations can help to develop fit-for-purpose interventions to end sexual violence within the earliest time possible.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study used a relatively large sample size which gave it statistical power to run rigorous analysis. Despite the rigour of the analysis and the high quality of the data used, readers must be mindful of the fact that the study followed a cross-sectional study design. Due to this, associations can be drawn but no causal relationship exists between the explanatory variables and the outcome variable. Social desirability bias is possible depending on societal acceptance or otherwise of sexual violence.

Conclusion

This sub-Saharan African-based study has demonstrated that women’s capacity in deciding on their healthcare is associated with lower odds of justifying sexual violence. The study points to the need to streamline sexual violence interventions in line with contextual variations in SSA. Groups that should be prioritised with anti-sexual violence initiatives are the poor, rural residents, and young women. It is also vital to institute policies and interventions focused on educating men about women’s right to make decisions, and why partner violence is unjust and intolerable. In addition, husbands and the broader society should be targeted for their acceptance and carrying out of the behaviour. Furthermore, building a women’s capacity for decision-making also requires the involvement of men and how men also shape this capacity. Future research may investigate factors that account for the age-driven discrepancy in attitude toward sexual violence whereby older women tend to have less support for sexual violence compared to younger women.

Data Availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Measure DHS repository http://www.measuredhs.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Measure DHS for making data accessible for this study.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

Since secondary data was used, no ethical approval was sought; however, permission was sought from Measure DHS for use of the data.