Mr. Speaker, our approach as a feminist government has been to invest in women, support women, invest in combatting gender-based violence, and ensure that women have recourse in difficult situations. We will continue to support women. We know that empowering women, encouraging women in the workplace, and protecting women who are victims of harassment or violence are at the core of any Canadian government's mandate.

—Justin Trudeau (Canada, 2018a)In 2015, Justin Trudeau led the Liberal Party of Canada to a majority win, ushering in Canada's first self-declared feminist government. Not only did Trudeau declare himself to be a feminist on the campaign trail (Trudeau, Reference Trudeau2015), the governing Liberals labelled specific policies feminist (for example, the Feminist International Assistance Policy); discussed the role of feminism in governing in interviews, including Tourism Minister Mélanie Joly, who said “we have a feminist agenda” (Harris, Reference Harris2019); and called itself a feminist government in debates in the House of Commons.Footnote 1 This self-declared feminist approach is central to understanding the Trudeau Liberals, since it was used to create a stark contrast with outgoing Prime Minister Stephen Harper and since the authenticity of the feminist label was a source of praise and scrutiny, domestically and internationally.

One might wonder: Were the 2015–2019 Trudeau Liberals truly feminist? Was it just rhetoric? These types of questions risk promoting a version of the co-optation thesis: states are only capable of appropriating and diluting feminist ideas toward advancing a non-feminist political agenda (see de Jong and Kimm, Reference de Jong and Kimm2017: 185). Arguing that the Trudeau Liberals are only cynically using feminism to advance non-feminist ends assumes that, first, mainstream political agendas cannot be compatible with or affected by any form of feminism and, second, only pure feminism exists outside politics. Such questions also miss the opportunity to understand what this feminist government label tells us about Canadian political discourse and political environment.

Applying the concept of governance feminism to the Trudeau Liberals can illuminate deep-seated assumptions about social problems and political change and identify the types of feminist discourses more palatable to Canadian politics. Governance feminism acknowledges that feminist ideas and actors do influence power (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein, Halperin and Hoppe2012; Halley, Reference Halley, Halley, Kotiswaran, Rebouché and Shamir2018a; Paterson and Scala, Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020). It accepts that the banner of feminism includes diverging stances about the problems and solutions. There is no unified feminism against which to measure the Trudeau Liberals. Applying governance feminism to the Trudeau Liberals does not ignore the possibility of instrumentalizing feminism. Rather, governance feminism allows for a sharper analysis investigating what types of feminism(s) gained traction and to what effect.

A government's approach to gender-based violence is a useful case study for understanding the types and effects of governance feminism. Gender-based violence refers to any form of violence in which someone is targeted because of their gender.Footnote 2 It is a persistent, systemic problem in Canada, borne out of durable systems of inequality. Meaningfully addressing gender-based violence requires moving beyond individualistic solutions in order to address structural problems. Feminist approaches to addressing gender-based violence sharply diverge on key issues. For example, carceral feminism has debated success in colluding with the state to expand punitive responses to gender-based violence (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein, Halperin and Hoppe2012; Taylor, Reference Taylor2018). Its influence has a negative effect, particularly on racialized, Indigenous, poor and disabled women. Other types of feminist arguments about gender-based violence may be less successful in influencing the state. Gender-based violence is also an excellent case study, as “combatting” it was central to the Liberals’ feminism claim. Investigating the feminist ideas at play in addressing gender-based violence contributes to an understanding of the role of feminist political discourse in Canadian politics.

This article investigates how gender-based violence was problematized in the speeches of the ministers of the Liberal cabinet in order to understand the types of feminist ideas and assumptions undergirding the 42nd Parliament. Ministerial speeches were selected because political discourse matters. Politics is all about speech. Understanding political speech reveals much about Canadian politics. Policy discourses shape policy action. Government speeches are policy pronouncements, especially for ministers under the tight message control of the prime minister and his office. Understanding policy discourses illuminates the framework shaping policy-making decisions. The framing of a problem creates and forecloses opportunities for action within the government and for those seeking to affect it (Brodie, Reference Brodie2008). Understanding government problematizations provides insight into the political environment and the actors that may have more opportunities to affect policy decisions. The way Liberal cabinet members deploy feminist ideas in their speeches about gender-based violence can tell us about the Canadian political environment, opportunities for change, and the assumptions underlying the strategic deployment of governance feminism.

This article employs Carol Bacchi's (Reference Bacchi2009) “What's the problem represented to be” (WPR) method to investigate the assumptions and silences in speeches by Prime Minister Trudeau and his ministers in the 42nd Parliament about gender-based violence. Speeches made in the House of Commons debates by Trudeau Liberals promised to eradicate gender-based violence and address the underlying systemic issues. Feminist ideas were clearly incorporated into the speeches. However, they promised to use the very systems complicit in perpetuating the violence, relying on neoliberal and carceral feminist ideas. In doing so, the Trudeau Liberals limited the social justice potential of incorporating feminist ideas into the policy debates about gender-based violence. This analysis of the official speeches of Liberal ministers from 2015 to 2019 about gender-based violence reveals that the Trudeau Liberals were open to feminist solutions to gender-based violence but relied on feminist ideas that perpetuate the status quo.

This article first situates the 42nd Parliament within a recent trajectory of Canadian anti-violence federal policy, contextualizing how the Trudeau Liberals differentiated themselves from the Harper Conservatives. The article then summarizes how governance feminism provides the theoretical grounding for this analysis. The methods section outlines WPR. Additional details about the inductive coding can be found in the appendix posted in Supplementary Material. The findings section then details three salient problematizations: (1) gender-based violence is preventable and systemic, (2) toughening the carceral state and people reporting their experiences are solutions, and (3) gender-based violence is an economic barrier and the result of a lack of information. The conclusion discusses future research potential as well as the implications for understanding the role of feminism in Canadian politics. The article reveals that the Trudeau Liberals may have campaigned on change, but the type of feminisms promoted in the speeches about gender-based violence limit the potential for change.

Gender-Based Violence and the Change Election

The 2015 election was a change election. Prime Minister Harper and the Conservative Party of Canada had governed since 2006. Throughout Harper's tenure, gender-based violence was often degendered and part of a broader criminal justice agenda (Knight and Rodgers, Reference Knight and Rodgers2012; Mann, Reference Mann2016). Funding was cut to Status of Women, the Family Violence Initiative, women's shelters and other social services (Brodie, Reference Brodie2008: 158; Fraser, Reference Fraser2014: 166; Mann, Reference Mann2016). The federal government made funding contingent on individuals and market rationality, further depoliticizing gender-based violence (Knight and Rodgers, Reference Knight and Rodgers2012). Harper refused to launch an inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), despite the mounting evidence of a severe problem (Beres et al., Reference Beres, Crow and Gotell2009; Palmater, Reference Palmater2016: 257).

The Harper government strategically made women and gender simultaneously invisible and hypervisible (Arat-Koç, Reference Arat-Koç2012). There was a focus on victims’ rights, lumping together victims of gender-based violence with victims of all crimes (Beres et al., Reference Beres, Crow and Gotell2009: 144). Crime victims were individuals without a context or social group. Racialized victims of gender-based violence, however, were spotlighted as victims of racialized and immigrant cultures (Arat-Koç, Reference Arat-Koç2012). This was clearly evidenced in Bill S-7 (2015) Zero Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices. The bill imagined a violent, barbaric foreigner who imports gender-based violence (Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2016). Human trafficking also created an opportunity to strategically invisibilize and spotlight women. In 2012, the Harper government created a National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking, which increased policing agencies’ funding in order to aggressively tackle the problem (Barnett, Reference Barnett2016: 11). Throughout its three terms, the Harper government simultaneously represented the problem of gender-based violence as a non-problem and as an extremely dangerous problem, sometimes imported by immigrants requiring punitive solutions (Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2016; Olwan, Reference Olwan2013).

In the 2015 election campaign, the Harper Conservatives doubled down on their record, while the Liberals campaigned on change. Preventing gender-based violence was central to the Liberals’ election promises. They promised to create a federal anti-violence strategy, invest in anti-violence service organizations, and modernize intimate partner violence and sexual assault laws. The Liberals critiqued the previous government for culturalizing gender-based violence and for not launching an inquiry into MMIWG. The inquiry was one of the first ambitious anti-violence policies undertaken after the Liberals formed government. They also turned inward, as the Canadian House of Commons passed a new code of conduct addressing sexual harassment between members of Parliament (Collier and Raney, Reference Collier and Raney2018). It is likely that there is some continuity with the previous government: neoliberal individual responsibility was central to the Harper government and continued under the Liberals (Gotell, Reference Gotelln.d.; Paterson and Scala, Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020). Stephanie Paterson and Francesca Scala argue that the Liberals’ use of feminist branding expanded feminist ideas beyond the departments tasked with gender equality while limiting the possibilities for social justice by focusing on gender equality through a neoliberal lens (Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020: 50). Similarly, Lise Gotell (Reference Gotelln.d.) contends that the Trudeau Liberals demonstrate the flexibility of neoliberal political imaginaries; these imaginaries can be expanded to include a progressive anti-violence agenda. Detailing how the Trudeau Liberals constructed gender-based violence as a problem while governing can provide insights into the nuanced and possibly contradictory relationship between the state and certain types of feminism.

Co-opted or Governance Feminism?

Most of the scholarship written on Liberal feminist government claims focus on foreign policy (Aylward and Brown, Reference Aylward and Brown2020; Brown, Reference Brown2018; Cadesky, Reference Cadesky2020; Robinson, Reference Robinson2021). Laura Parisi (Reference Parisi2020), for example, analyzed Canada's Feminist International Assistance Policy (FIAP) using WPR. That FIAP focuses on integrating women into the economy to alleviate poverty and advance gender equality demonstrates FIAP's neoliberal feminism (Parisi, Reference Parisi2020). For some, the continuity of the spending by the Liberals and previous governments demonstrates that the feminist label is a branding tool, meant to please the Liberals’ base rather than meaningfully guide effective aid policy (Brown, Reference Brown2018: 151). This argument accords with Jessica Cadesky's (Reference Cadesky2020) analysis—gender and feminism are strategically overpoliticized and depoliticized in FIAP in order to advance the government's agenda. The common thread in these articles is a suspicion of the feminist label.

The question becomes, Can a government ever be feminist? One line of argumentation suggests that states, especially neoliberal states, co-opt feminism toward their own ends. Co-optation refers to “the appropriation, dilution and reinterpretation of feminist discourses, and practices by nonfeminist actors for their purposes” (de Jong and Kimm, Reference de Jong and Kimm2017: 185). This undoubtedly happens, although assuming that governments are only capable of co-opting feminism overlooks feminist actors who are ensconced in the machineries of power and who have created opportunities for feminist policy development (Eschle and Maiguashca, Reference Eschle and Maiguashca2018; McBride and Mazur, Reference McBride and Mazur2010; Scala and Paterson, Reference Scala and Paterson2017: 429–30). It also circumscribes binaries between feminists and feminist ideas that are true/false, good/bad and resistant/co-opted (Eschle and Maiguashca, Reference Eschle and Maiguashca2018; Scala and Paterson, Reference Scala and Paterson2017). A more nuanced analysis that looks beyond co-optation is required to more fully capture the relationships between the state and feminism.

The concept of governance feminism allows us to understand what “the installation of feminists and feminist ideas in actual legal-institutional power” (Halley, Reference Halley2006: 340) tells us about gender-based violence discourses. Governance feminism is preoccupied with the ways in which neoliberalism influences people to control themselves as rational, responsible individual citizens. It is assumed that feminists and feminist ideas can influence power, often in line with neoliberal ideas (Halley, Reference Halley, Halley, Kotiswaran, Rebouché and Shamir2018a: 3). This aligns with the literature detailing the struggles and successes of feminists in government bureaucracies, feminists in elected positions, and feminist ideas in governing (Eisenstein, Reference Eisenstein1996; Findlay, Reference Findlay2015; Hankivsky, Reference Hankivsky2005; Scala and Paterson, Reference Scala and Paterson2017). Gender-based violence is one area in which feminist ideas have, at times, influenced state power (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein, Halperin and Hoppe2012; Halley, Reference Halley, Halley, Kotiswaran, Rebouché and Shamir2018a). This should not be confused with the state enacting an imaginary perfect feminist response. But rather, governance feminism points to the effect of feminist ideas. Governance feminism can be distinguished from times when the state has been hostile to feminist ideas about gender-based violence. In Canada, this includes attempts to downplay the significance of the issue, degender the violence or outright blame victims. In the case of the Trudeau Liberals, a clear attempt was made to appear feminist by claiming to have a feminist agenda and by tackling policy problems often associated with feminism such as gender-based violence. Governance feminism provides a theoretical grounding to understand how feminist ideas are enfolded, challenged and reinterpreted through the state apparatus.

Feminist arguments critical of the state or in favour of more radical change are harder for political actors to espouse and incorporate into governing. Instead, what has been called neoliberal feminism is more palatable. Alexandra Dobrowolsky argues that the Trudeau government has focused on neoliberal feminist ideas and the superficial applications of intersectionality (Reference Dobrowolsky, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020: 24). In the co-optation thesis, any neoliberalized form of feminist ideas would be thought to be bastardized forms of “good” resistant feminism. However, this thesis overlooks the ways in which feminist ideas and market rationality have merged and, as a result, changed how states have attempted to address gender equality. Dobrowolsky offers a good overview of the difference between the state feminism of the 1970s and 1980s and neoliberal feminist state approaches; whereas the former focused on building gender equality state institutions, the latter focuses on gender equality as a market problem that can be solved by cultivating good individual feminist subjects invested in their own development of human capital (Reference Dobrowolsky, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020: 29). Governments adopting neoliberal feminist agendas typically represent gender-based violence as an economic empowerment issue.

Individualized subjects and market rationality with a feminist tinge are more palatable to current state mechanisms, just as carceral feminism aligns with the punitive state (Halley, Reference Halley, Halley, Kotiswaran, Rebouché and Shamir2018b). Carceral feminism occurs when feminist analyses of gender-based violence have shored up carceral state expansion (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein, Halperin and Hoppe2012; Bumiller, Reference Bumiller2008; Taylor, Reference Taylor2018).Footnote 3 The resulting expanded carceral state negatively affects marginalized communities, exacerbates some cases of gender-based violence and, at times, targets victims of violence (Abraham and Tastsoglou, Reference Abraham and Tastsoglou2016; Goodmark, Reference Goodmark2018).

While the concept of governance feminism has been empirically studied in the Canadian context (Parisi, Reference Parisi2020; Paterson and Scala, Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020), critiques of carceral feminism have received less empirical attention. Evidence indicates that the anti-violence carceral system in Canada negatively affects immigrant, racialized and Indigenous people (Abraham and Tastsoglou, Reference Abraham and Tastsoglou2016; Palmater, Reference Palmater2016) and that the federal government has favoured carceral responses to gender-based violence (Gotell, Reference Gotelln.d.). Scholars continue to debate the extent to which feminists successfully influence the state to implement carceral responses to violence against women (Bumiller, Reference Bumiller2008), with some arguing that the Canadian state appropriated feminist discourses to advance carceral logics (Gotell, Reference Gotell, Powell, Henry and Flynn2015; Sheehy, Reference Sheehy1999: 65). An analysis of ministerial speeches is informative, both to assess the ways in which gender-based violence were problematized by ministers in the 42nd Parliament and to investigate the feminist logics undergirding these problematizations.

Methods

This article applies Bacchi's (Reference Bacchi2009) “What's the problem represented to be?” (WPR) approach to consider how gender-based violence is constituted as a problem in the speeches by Liberal ministers. Each policy pronouncement constructs gender-based violence as a specific problem and, in doing so, creates real-world effects in the lives of those affected by the problem and policy responses (Bacchi and Eveline, Reference Bacchi, Eveline, Bacchi and Eveline2010: 111; Paterson, Reference Paterson2010). By focusing on how problems are constituted, this approach promises a deeper understanding of the policy “by probing the unexamined assumptions and deep-seated conceptual logics implicit within problem representations” (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi, Bletsas and Beasley2012: 22). The goal is not to deny the existence of gender-based violence as a problem or to define the “real” problem, as Alisa Grigorovich and Pia Kontos likewise argue (Reference Grigorovich and Kontos2020: 117). Instead, the goal is to contribute to an understanding that might result in new imaginings about alternative anti-violence policies. In adapting Bacchi's framework (Reference Bacchi, Bletsas and Beasley2012: 21), this article investigates the following questions:

1. What's the problem of gender-based violence represented to be in speeches made by Liberal ministers in the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019)?

2. What deep-seated presuppositions, assumptions and logics underlie the presentation(s) of the problem of gender-based violence?

3. What is left unproblematic in the problem representation(s)? Where are the silences? How can the problem be conceptualized differently?

The first question is meant to illuminate the problem representation, the second to reflect on underlying premises and the third to scrutinize limitations in the representation that likely circumscribe the political imaginary in political speeches (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi, Bletsas and Beasley2012: 22).

How politicians talk is important. One can understand House of Common debates, especially those delivered by federal cabinet ministers, as forms of policy pronouncements (see Bacchi, Reference Bacchi, Bletsas and Beasley2012: 22). Stated more grandiosely, political thought has long considered politics a matter of speech (Chilton and Schäffner, Reference Chilton, Schäffner, Chilton and Schäffner2002; Saurette and Gordon, Reference Saurette and Gordon2013: 157). One can also view these speeches as promises for action and signals for change. What bills they pass is one thing, but how they talk about an issue signals how they want the voter to view their actions. Parliamentary debates and speeches are also forms of institutional politics. Since neoliberalism is “knowledge-driven,” discourse is central to understanding the neoliberal political order (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough, Harrison and Young2004). Here, I am invoking Bacchi's conception of discourse as “forms of social knowledge that make it difficult to speak outside the terms of reference they establish for thinking about people and social relations” (Reference Bacchi2009: 35).Footnote 4 Analyzing speeches is a way of understanding the deep-seated presumptions that shape how social problems are governed.

This article specifically analyzes House of Commons speeches by the prime minister and cabinet in the 42nd Parliament. Through a comprehensive keyword search on Hansard,Footnote 5 all 266 speeches by Trudeau and his ministers that pertained to gender-based violence were collected. Speeches were analyzed as self-contained texts and as part of a debate using an iterative qualitative coding process on MAXQDA (see appendix posted in Supplementary Material). The goal of the coding was not to quantify the patterns but rather to give a nuanced view of gender-based violence problematizations in executive speeches in the House of Commons.

What ministers say matters insofar as they are relaying a highly scripted and co-ordinated central message that reflects the consolidation of power among the prime minister and the executive (Chamberlain, Reference Chamberlain2021; Savoie, Reference Savoie1999; Lewis, Reference Lewis2013; Marland Reference Marland2020). Cabinet interventions about gender-based violence constitute a form of governance where feminist ideas are presented, challenged and reinterpreted through the state apparatus. Speeches about gender-based violence in the House of Commons are forms of policy, and studying them provides insight into the types of feminism promoted for Canada's first self-declared feminist government.

Problematizations in the 42nd Parliament

Ministers referred to gender-based violence generally or to specific forms, namely sexual violence, domestic violence, MMIWG and human trafficking. Violence against queer people was discussed less, even though ministers included anti-LGBTQ violence within the definition of gender-based violence in their speeches. For example, a few speeches about Bill C-16 in 2016 by Status of Women Minister Patty Hajdu and Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould outlined the importance of addressing violence against trans individuals to explain why gender diversity was added to the Canadian Human Rights Act and Criminal Code. Aside from a few mentions, cabinet generally did not discuss violence against trans or gender queer people.

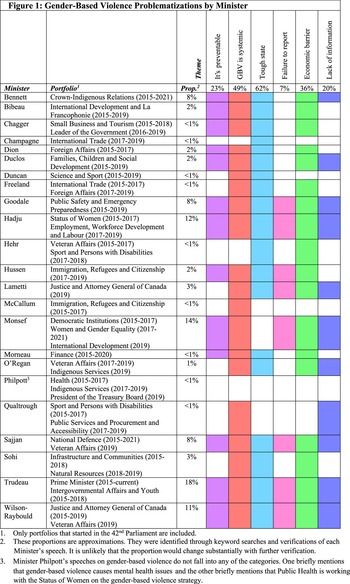

As Figure 1 shows, ministerial speeches problematized gender-based violence in a contradictory manner.Footnote 6 On the one hand, ministers describe gender-based violence as an eradicable social problem with systemic and institutional causes. This radical problematization appeared in a quarter of the speeches delivered by a diverse group of ministers from International Development (Marie-Claude Bibeau) to Public Safety (Ralph Goodale) to Justice (Wilson-Raybould). On the other hand, ministers also espoused carceral feminist and neoliberal ideas. That gender-based violence requires a tough state response was the most resounding theme: it was present in the highest proportion of speeches and said by all but four ministers. Economization of violence and the focus on data gathering also proliferated, showing up more than the progressive suggestion that gender-based violence is preventable. The overall messaging suggests that action toward transforming systemic and institutional failures is secondary to studying the problem, bolstering human economic potential and toughening the state's response to the violence. Ministers reiterated that gender-based violence needs a strong state approach and survivors simply need to report the violence to get justice and that gender-based violence is an economic barrier that only requires more information, inquiries and surveys to solve. The echoing silence on the people and specific structures that cause harm lays bare the tension: the speeches nod to transformational feminist anti-violence problematizations while bolstering the very systems, processes and institutions that reproduce and entrench gender-based violence.

Figure 1 Gender-based violence problematizations by minister

Transformational potential: Gender-based violence is preventable and systemic

In the 42nd Parliament, Liberal leadership discussed all forms of gender-based violence—sexual violence, violence on campus, MMIWG, sexual harassment, human trafficking and domestic violence—as immense yet realistically preventable and eradicable problems.

Our government is working hard to end gender-based violence at home and all over the world. Why? Because it is unthinkable that this is a reality in Canada. It is costing our economy over $12 billion a year. (Canada, 2019a, Monsef)

One of our first priorities is to address the urgent need to reduce and prevent gender-based violence in our society. It goes without saying that violence against women is not acceptable and should not be tolerated in our society. (Canada, 2016a, Hajdu)

Canada will only reach its full potential when everyone has the opportunity to thrive, no matter who they are or where they come from. To achieve this, we need to work together to prevent gender-based violence. (Canada, 2018b, Trudeau)

This problematization posits that gender-based violence is a “reality.” Ministers declare that prevention and eradication are possible. Preventing is a less ambitious goal, as it could mean stopping most violence from happening. Ending gender-based violence is an ambitious goal, as it demands elimination, eradication and extermination. Ending the violence requires multiple mandates, if not generations.

Various strategies are suggested to end violence. The MMIWG inquiry is framed as something that will “put an end to this tragedy” (Canada, 2015, Trudeau). The federal anti-violence strategy and funding for women's shelters led the government to suggest it was “confident that this range of actions will reduce violence and end this scourge against our society” (Canada, 2016b, Hajdu). The idea that the federal strategy and the national inquiry into MMIWG would prevent and end gender-based violence reverberated in the 42nd Parliament.

By labelling gender-based violence a systemic problem, the ministers acknowledge that ending it would be incredibly challenging. Systemic problems are embedded in institutions and the fabric of society. Ministers relayed that gender-based violence is often caused by misogyny, sexism, discrimination, racism and culture. These systems of oppression were frequently mentioned without any details. At the highest level of abstraction, Prime Minister Trudeau mentioned “the systemic and institutional failures that resulted in this tragedy [MMIWG]” (Canada, 2018c). He offered no explanation of those failures. A system of oppression is often mentioned but not explained. Crown–Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett said that they needed to “get going now” on “racism, sexism, policing, and the total overhaul of the child welfare system” (Canada, 2016c). Women and Gender Equality Minister Maryam Monsef similarly mentioned “misogyny and sexism” in several speeches, with only a few fleshing out the cultural hatred of women and structures of gender inequality (Canada, 2017a). Overall, ministers tended to label the problem as systemic but to obscure what that entails.

Problematizing gender-based violence as a preventable, systemic issue is potentially transformational. It rejects the belief that boys will be boys and the notion that gender-based violence is an inevitable part of masculinity and society. Yet men, masculinity and people who cause harm are not discussed. As Paterson and Scala discover about the broader gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) approach of the Liberal government, “Men are not asked to change and masculinity is accepted as given” (Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020: 56). Likely because of this silence, preventing gender-based violence can sound transformational without making aggressors feel uncomfortable.

Preventing gender-based violence raises the question: Against whom and in what setting? Despite the fact that prisons are ineffective tools of rehabilitation of offenders and that contact with the criminal justice system may increase violence (Goodmark, Reference Goodmark2018), prisons as sites of sexual violence and the exacerbation of gender-based violence through contract with the criminal justice system are not discussed. The government instead presents a picture of gender-based violence that is congruent with popular understandings of prevention through punishment, without explicitly saying so. The speeches nod to a potentially transformational problematization of gender-based violence as an eradicable problem caused by systems of oppression without detailing the institutions, systems and people causing harm.

A carceral approach: Toughen the state, report the violence

Ministers position the criminal justice system as the solution for many harmed by gender-based violence. Survivors should report to police to get justice. The MMIWG inquiry is about getting justice for the families. What constitutes justice is not interrogated or explained. Speeches by cabinet ministers include subtle critiques of the criminal justice system, but often that it is not tough enough. Justice is assumed to mean punishment for the abusers and killers, without explicitly mentioning aggressors. It is easier to discuss punishment of an imagined monster than accountability of real grandfathers, fathers, husbands, sons, friends and so on.

Ministers used “toughness” and “strength” to communicate the goals of criminal justice reform. Justice Minister Wilson-Raybould said the government wanted to “strengthen the law of sexual assault” (Canada, 2018d). Regarding Bill C-65 that amended the Canada Labour Code to address harassment and violence in federally regulated industries, Employment, Workforce Development and Labour Minister Hajdu said: “It would strengthen a fabric that would set a baseline of intolerance for harassment and violence” (Canada, 2018e). The government is also “committed to strengthening the efforts to combat” human trafficking (Canada, 2016d, Wilson-Raybould). Using tough language and advancing the criminal justice system is compatible with governance feminism; this is an example of how types of feminist knowledge—here, carceral feminist ideas—are integrated in political discourse.

Ministers’ speeches emphasized a tough state response to domestic violence and to human trafficking in particular. Bill C-75 aimed to amend several aspects of the Criminal Code,Footnote 7 including “toughen[ing] criminal laws and bail conditions” for repeat domestic violence offenders (Canada, 2019b, Lametti). The bill “gives police officers and prosecutors a new tool” to make it more difficult for repeat offenders to access bail and increases the maximum penalty for them (Canada, 2019b, Lametti). Human traffickingFootnote 8 is almost exclusively framed as a criminal justice problem that requires a tough state response to “combat” it, “crack down” on it and to “protect” exploited victims. Human trafficking justifies the expansion of state powers. For example, Bill C-21 strengthened the Canada Border Services Agency's powers to collect information on people leaving Canada. Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Minister Ralph Goodale explained:

It would also be useful in Canada's efforts to combat human trafficking. It could help police determine the location of a suspect or a victim of human trafficking. It could help determine the travel patterns of suspects or victims, which in turn makes it easier to identify human smuggler destinations or implicated criminal organizations, and it could help police to identify other suspects or victims by learning who is travelling with the individual in question. All of this information is invaluable not only for the advancement of human-trafficking investigations but also later in the criminal justice process in support of ensuing prosecutions. (Canada, 2017b)

While other solutions are mentioned to address domestic violence (such as funding women's shelters), human trafficking is exclusively a problem that requires a muscular state. Highlighting that the problem is one of a too lenient and ineffective criminal justice system aligns with carceral feminism: gender-based violence requires more police, more punishment and more prosecution to eradicate.

Some ministers also called on survivors to report the violence to a toughened criminal justice system. The problematization of non-reporting was most prominent in discussions of sexual violence and harassment in the military and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). In a speech defending Bill C-51,Footnote 9 Minister Wilson-Raybould emphasized that legal reforms would “foster an environment where sexual assault complainants feel empowered to come forward for justice and support” and “feel encouraged to come forward and report their experiences to police” (Canada, 2018d). Reporting is equated with empowerment and violence reduction. The prime minister made a similar point: “We are creating a justice system and a system of policing that actually enable[s] survivors of sexual assault to come forward and get justice” (Canada, 2017c). Trudeau and his ministers reiterated that the police and criminal justice system are justice givers and that survivors must “come forward” to receive this justice.

Sexual harassment is problematized as the partial result of a victim's silence, especially in discussions of sexual harassment in the military and RCMP. National Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan said: “We encourage all members to come forward” (Canada, 2018f). Solutions highlighted in the discussion of Operation HONOUR—a military mission aimed at tackling sexual harassment and misconduct, based on the recommendations of former Supreme Court Justice Marie Deschamps’ report—focused on “a new victim response centre, better training for Canadian Armed Forces personnel and easier reporting” (Canada, 2018g, Sajjan). A survivor's failure to report is emphasized, with little discussion of the barriers to reporting and failures of the chain of command to respond appropriately. Ministers do not note that people might not want and do not have to report or that complainants may face a backlash. Ministerial speeches locate the problem in victim behaviour and courage, thereby suggesting that change will come from reporting.

A neoliberal approach: Economic barriers and inquiries

Liberal ministers problematized gender-based violence as a barrier to an individual's economic success and the country's economic growth. Sexual harassment in the workplace was one example. In discussions of Bill C-65, Minister Hajdu said: “We take this action because our government recognizes that safe workplaces, free of harassment and violence, are critical to the well-being of Canadian workers and critical to our agenda of a strong middle class” (Canada, 2018h). This theme was also prominent in Minister Monsef's speeches about gender-based violence. In one of her December 6 speeches, Minister Monsef said “the best way” to honour the victims of the 1989 Montreal Massacre was “to end gender-based violence, to show intolerance toward misogyny and to work to advance an economy where everyone benefits” (Canada, 2018d). The minister also framed the death of 14 women in the Montreal Massacre, targeted for being women and feminists, as having negative economic effects, for the lost “potential” and “lost engineers” (Canada, 2018d). She wrapped by saying: “It was a tremendous loss for our nation. We will never know what they may have achieved” (Canada, 2018d). Minister Monsef made the point that gender-based violence is an economic barrier in another speech:

Advancing equality and preventing gender-based violence is the right thing to do. It is also the smart thing to do. I am sure my hon. colleague knows that domestic violence is costing us $12 billion a year. I am sure my hon. colleague knows that, if given the choice, many would prefer to be out and reaching their full potential and contributing to society and the economy. (Canada, 2018i)

Minister Monsef suggests that murdering women negatively affects society and the economy. This ties a woman's worth to her market productivity as well as her broader influence on society. It suggests that one cannot reach their full potential if they experience gender-based violence. While women's potential goes beyond economic production, Minister Monsef clearly frames potential in economic, neoliberal terms.

This neoliberal problematization is congruent with the critiques that the Trudeau Liberals use feminist ideas to advance neoliberal notions in other policy areas (Paterson and Scala, Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020). Just as FIAP looked to add women to the economy (Parisi, Reference Parisi2020), emphasizing the economic consequences of gender-based violence advances a market rationalization of gender-based violence. Treating gender-based violence as important because of lost wages and productivity reinforces the idea that women are worthy as productive, economic actors. Ending gender-based violence is deprived of its transformational potential as a key beneficiary of the policy in expanded economic growth.

The neoliberal tendrils further ground the problematization through an emphasis on information gathering. The question of sexual harassment in both the RCMP and military are problematized as under-known issues. Minister Goodale first mentioned sexual harassment in the RCMP by explaining how the government was undertaking “a comprehensive review of RCMP policies and procedures to evaluate the implementation of recommendations against harassment” (Canada, 2016e). Operation Honour is likewise presented as one of the key solutions to sexual harassment and violence in the military, which included a survey meant to get the full extent of misconduct. As Minister Sajjan explained: “This survey was part of that plan [Operation Honour] to get the full extent of the situation. Now this provides the necessary information to continue to evolve the plan, moving forward” (Canada, 2016f). The government also provided funding to the Canadian Network of Women's Shelters & Transition Houses “to collect better data” (Canada, 2016g). Focusing on the problem as a lack of information may be a stall tactic, but it is also problematizes the issue as an under-known problem that requires technocratic information-seeking activities.

This theme was prominent in the discussion of MMIWG. Prime Minister Trudeau and the two ministers responsible for Indigenous relations (Carolyn Bennett and Seamus O'Regan) reiterated that inquiry was about getting justice through getting answers. For example, Minister Bennett said: “We are determined to give the families the answers they have long been looking for about the systemic and institutional failures that resulted in this tragedy” (Canada, 2018j). The inquiry in and of itself suggests that the problem is, in part, a lack of information, something that requires more study. There was some incoherence in this problematization of MMIWG specifically. Minister Bennett said early in the process: “We cannot wait for the result of the commission. We need to get going now on housing, shelters, and safe transportation, but also racism, sexism, policing, and the total overhaul of the child welfare system” (Canada, 2016c). The contradiction of knowing and not knowing is central to understanding this theme. The causes of MMIWG, sexual harassment in the military and in the RCMP, and domestic violence more broadly are well known to the government, but ministers represented them as unknown and thus in need of further study.

Conclusion

Canada's first self-declared feminist government hampered its own progressive problematization of gender-based violence. The transformational potential of ending gender-based violence was recuperated into the neoliberal and carceral state in which market rationality and punishment are key vectors of state power and control. The government that promised radical social change (end gender-based violence) also promised to strengthen the systems that participate in causing harm (the free market and punishment). Yet neither neoliberal nor carceral feminism totally explain the pattern of speeches delivered by government ministers about gender-based violence. A focus on market rationality and carceral solutions sat alongside potentially transformational promises to address institutional failures and to end gender-based violence.

This is why the co-optation thesis falls short and why governance feminism is analytically useful in explaining the relationship between feminism and the state in Canadian politics. Not only are carceral feminist ideas forms of feminism; the Liberals also clearly incorporated progressive feminist definitions of gender-based violence and its solutions into their policy pronouncements. Feminism provides an expansive framework to justify a range of ideas and programs. Problematizing gender-based violence as preventable is an expansion of feminist political knowledge (see Paterson and Scala, Reference Paterson, Scala, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020). This problematization assumes that government action can and should be used to end the violence, although the silences on men, masculinity and the details of the systemic nature of gender-based violence suggest that the political imaginary of ending gender-based violence is limited. The continued emphasis on tough state responses confirms that certain types of feminist knowledge are more attractive to state power. Canadian governance has space for feminist ideas. However, even for a government that adopted progressive feminist understandings of gender-based violence, neoliberal rationality and carceral feminism remain steadfast.

Several fruitful areas of future inquiry could follow this study. In what ways did the Trudeau Liberals break from the past and in what ways did they continue the status quo? That the Harper Conservatives refused to support an inquiry into the epidemic of violence against Indigenous women and girls, while using the guise of violence against racialized immigrant women to argue for increased carceral interventions for racialized immigrant men, suggests that the tenor of the two governments was indeed different. Yet Harper and Trudeau promoted the carceral system to solve gender-based violence. Where they align, and differ, would reveal more about the state's relationship to gender-based violence and further investigate the openness of Canadian political institutions to change. Future research could seek to understand how closely the speeches as policy pronouncements align with policy documents or the lived effects for those who are subjected to or cause gender-based violence. It could also consider the effect on voters of declaring the government to be feminist. Did it expand or contract who was willing to vote for the Liberals? Finally, governance feminism and carceral feminism, in particular, suggests that feminist ideas and actors influence the state. While this article reveals the way certain feminist ideas were taken up in Liberal ministers’ speeches, additional work could further illuminate the personal and structural relationships between feminist actors and the state. What did anti-violence advocates, for example, lobby for during their engagement with federal government in developing the anti-violence strategy? How did the emphasis on carceral and neoliberal feminism shape the political environment? What actors saw openings and what actors faced more barriers to influence policy? Such an analysis would complement and add nuance to the findings presented here.

This article opens the door to ponder why Canada's most self-described feminist government to date fell short of its own potential. Is it simply a problem of the government overpromising and underdelivering? Are cynics correct that transformational feminist ideas are incompatible with state power? An unsatisfactory response might be that all feminist talk is just branding. A more compelling response might be that neoliberal and carceral rationality are entrenched in the Canadian state. Following Gotell's (Reference Gotelln.d) argument, we could view these speeches by Liberal ministers as examples of the ability of neoliberal governance to incorporate progressive feminist ideas. Without changing these stalwart rationalities, any promise of transformation is doomed to fail. Even well-intentioned efforts to eradicate gender-based violence will fall flat without an understanding of the role state institutions play in perpetuating gender-based violence, from the prison to economic inequality to ongoing colonial practices. The deep systemic issues perpetuating gender-based violence require more change than the Liberals—or most governments, for that matter—are willing or able to tackle in a single mandate.

Acknowledgments

This work started under the support of a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship [award number: 162667] and was completed thanks to the support from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council [grant number: 430-2022-00048].

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423923000707