Introduction

Caring for family members with dementia may lead to personal growth, accomplishment, purpose, and family cohesion. Nevertheless, many dementia family caregivers (DFCs) experience depression and anxiety.

DFCs increasingly tend to be older adults in the ‘sandwich generation’, caring for parents and partners with dementia, in addition to children and grandchildren. These carers may struggle adapting to life transitions such as retirement, whilst facing a reversal in their roles. DFCs also face barriers to seeking help, such as feelings of guilt for feeling their role is a ‘burden’, and loneliness if they seek respite.

Cognitive behavioural models of depression and anxiety for these invisible second patients suggest that carers may have certain cognitive biases and negative automatic thoughts about themselves and others, including professionals. They may also worry about their ability to cope as dementia progresses. Losada et al. (Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015) devised a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) programme which tackled four components: firstly, cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional thoughts about caregiving; secondly, assertive skills such as asking for support; thirdly, building relaxation strategies; and finally, increasing engagement in pleasurable activities. This programme has been supported by a randomised controlled trial demonstrating its effectiveness (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015).

CBT is recommended for DFCs by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2020), and the research has illustrated that CBT can alleviate distress in these individuals, by increasing pleasurable activities and altering unhelpful caregiving beliefs (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015). However, each family context may vary and thus carers may require individualised interventions. Most research has also focused on those who provide dementia care for solely one family member. The current study aims to evaluate CBT for an older adult experiencing low mood and anxiety around caring for not just one, but two family members with dementia.

Referral

Mrs P was a 68-year-old lady in the ‘sandwich generation’, who had been caring for her mother with dementia for years without requiring psychological support. When Mrs P’s husband was diagnosed with mixed dementia in 2019, he denied his diagnosis, and his condition deteriorated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mrs P was subsequently referred for confidential psychological support with a therapist at the local Memory Service (L.F.).

Method

Design

A single-case experimental study with an A–B design was adopted to evaluate the impact of an 8–session CBT intervention.

Assessment

Clinical interview

Although she stated she had always been ‘strong person’, Mrs P felt low, anxious, guilty, and overwhelmed by her new, additional caring role for her husband. She struggled to get out of bed in the morning, and no longer engaged in hobbies she enjoyed, such as learning Spanish. She felt more physically and mentally unwell, started taking fluoxetine and sleeping tablets, and did not socialise with others.

Measures

Due to Mrs P’s unhelpful thoughts about caregiving perpetuating her low mood and anxiety, the Thoughts Questionnaire (TQ) for Family Caregivers of Dementia (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Beattie, Khawaja, Wilz and Cunningham2016) was used alongside the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9: Kroenke and Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002), and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7: Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) which were routinely used in the memory service. These measures have been shown to have robust psychometric properties.

Hypotheses

It was hypothesised that modifying Mrs P’s dysfunctional thoughts and increasing her engagement in pleasurable activities would make her feel less anxious and depressed.

Formulation

Although systemic factors including cohort beliefs, intergenerational factors and sociocultural factors appeared linked to Mrs P’s presentation, due to Mrs P’s distress during sessions, Charlesworth and Reichelt’s (Reference Charlesworth and Reichelt2004) guidance for simple case conceptualisations for anxiety and depression in DFCs was used. Subsequently, a vicious flower was formed collaboratively with Mrs P to understand current maintaining factors for Mrs P’s difficulties (shown in the extended report in the supplementary material).

Mrs P’s early experiences with a ‘critical’ mother made her set high expectations of herself, which if she did not meet, meant she was not ‘good enough’. However, her husband’s dementia diagnosis was considered a critical incident triggering difficulty.

Recent experiences of low mood and anxiety were explored to identify maintenance factors involving thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, and behaviours. The downward arrow technique identified that if she could not provide ‘perfect care’, this would mean that she is ‘pathetic and not good enough as a carer’, leading her to feel extremely low and hopeless about the future. This was coupled with catastrophic worries about bad things happening in the future linked with the degenerative nature of dementia, and her husband’s dementia being different from her mother’s. She would even frequently ask herself: ‘What if I get dementia?’, which made her feel severely anxious.

Mrs P was not motivated to spend time on household tasks. She developed rigid beliefs that if she cared for herself, even when sick, this would mean she is a ‘bad carer’, leading to intense feelings of guilt. Yet, if she supported her husband, she was criticised, further confirming her uncompassionate self-beliefs. At the same time, due to cultural family values about ‘status’, she would not seek outside help.

Due to COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, Mrs P’s caring role for her mother adapted to telephone support and distanced visits between a glass screen and protective equipment. She also spent even more time with her husband, which increased tensions, responsibilities, and made her more aware of when things went wrong. She procrastinated with household tasks, which was positively reinforcing in the short-term, but in the long-term meant family affairs were not in order which caused more distress and confirmed negative beliefs about her caring abilities and the future.

Mrs P set a goal of being able to manage her thoughts and feelings when activities of everyday life did not go to plan with her husband, for example, whilst shopping.

Intervention

Treatment consisted of a consultation and eight 1-hour CBT sessions delivered at an NHS Memory Service, based on NICE guidelines and Losada et al.’s (Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015) programme of CBT for DFCs and collaboratively adapted with Mrs P based on her family context and family members’ dementia.

The intervention phase started with Mrs P’s low mood, which was a barrier to engaging in later components of treatment. A thought record sheet facilitated Mrs P’s understanding of common situations where things may go wrong with her husband, such as him getting lost whilst shopping, or arguments. Mrs P participated in cognitive restructuring, involving taking alternative perspectives, and Mrs P realised that because of her efforts, there had been few occasions when things have gone wrong.

Next, the negative core beliefs Mrs P were extracted from the TQ, and used to conduct a behavioural experiment into how other people would respond in a scenario where they were DFCs. All participants in the survey believed that you would have to take care of yourself before any family members, all people said they would accept outside help, and all participants said if you do not always get things right or if caregiving did not go to plan, this does not mean you are a ‘failure’. Mrs P described this as a ‘turning point’. This opened up a discussion about how being a good or bad carer is not ‘all or nothing’, and that caregiving is on a continuum. This also enabled responsibility to be assigned to different people and variables in challenging situations for Mrs P and her husband (including externalising her husband’s dementia), thus supporting Mrs P in realising things may go wrong but this may not be her fault.

Mrs P was provided with psychoeducation around her husband’s mixed dementia, including how it might impact interactions at home, whilst also helping her to externalise the problem; she stated that dementia is unpredictable and when things go wrong, it might be ‘dementia’s fault’.

Subsequently, Mrs P unfortunately suffered an abscess, although she explained that she used this as a behavioural experiment to test out feared consequences that something catastrophic would happen to her husband if she could not support him. This taught her the importance of the metaphor of ‘not being able to give from an empty cup’, and Mrs P practised several relaxation breathing scripts to introduce her to ways to care for herself. She also reflected on her weekly schedule, and collaborated with the therapist to find time to reclaim her life via new hobbies and interests through activity scheduling. Mrs P attempted to shift her time to learn Spanish to the morning rather than at midnight, to remove a barrier to her sleep hygiene and also motivate her in the mornings, which helped interrupt ruminative thinking patterns and break obstructive cycles of avoidance during daily life.

Lastly, a blueprint was created to plan for the future. Mrs P anticipated appointments and conversations about her husband not driving (considered in the risk management plan) to be difficult in the future. She produced the following messages to remind herself: ‘You’re not a bad person’, ‘You must take care of yourself’ and ‘Take back interest in yourself’.

Results

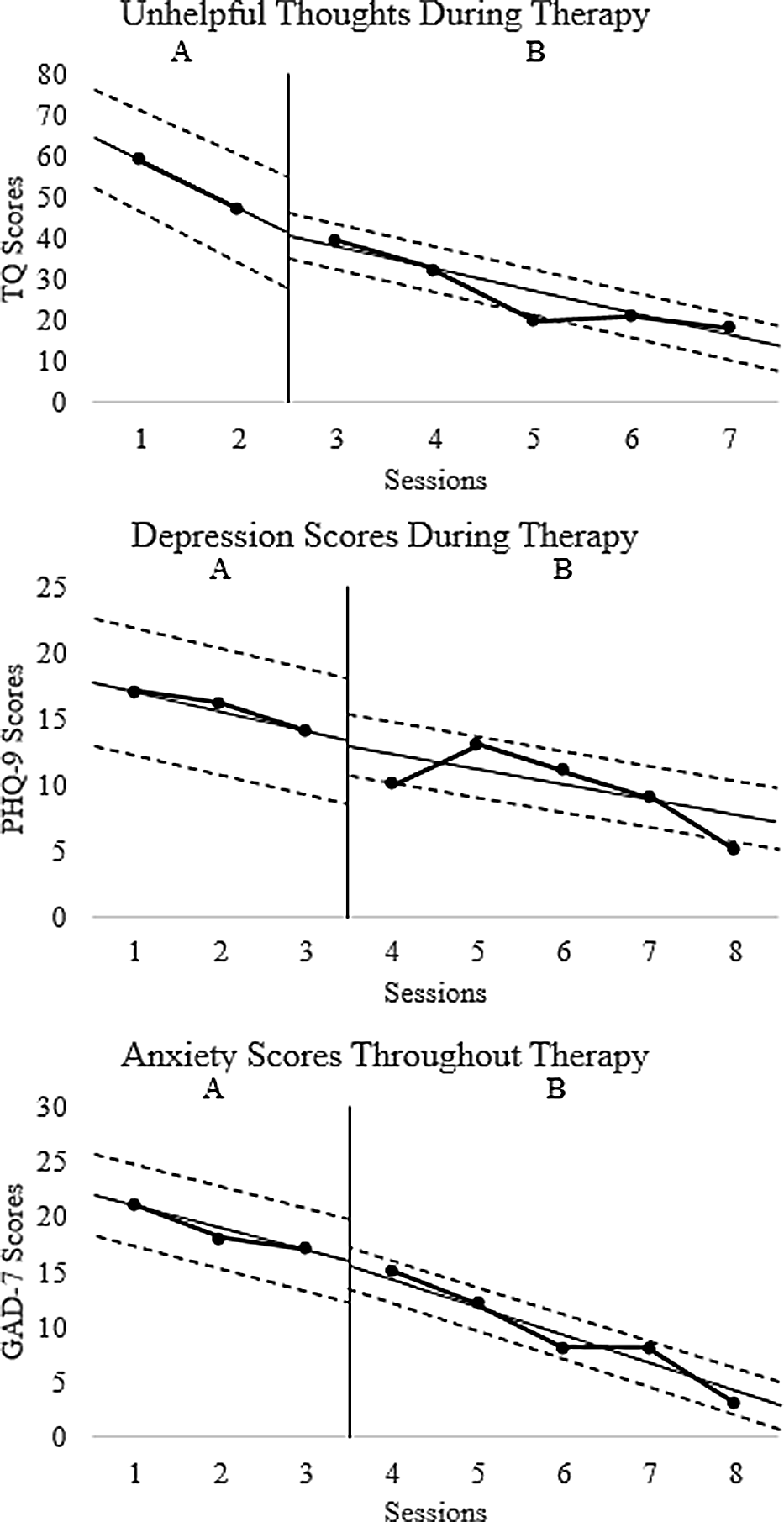

Mrs P’s unhelpful thoughts decreased throughout therapy. Mrs P’s depression also reduced from moderate to just meeting the threshold of mild, and anxiety reduced from severe to the normal range (see Fig. 1). Mrs P also reported meeting her goal of becoming better at managing situations where things did not go to plan whilst caring for her husband. Subsequently, Lane and Gast’s (Reference Lane and Gast2014) guidelines on visual analysis for A–B single case experimental design research were followed.

Figure 1. Mrs P’s scores for unhelpful thoughts about caregiving, depression and anxiety throughout treatment.

The mean, median and range of scores for each measure in both conditions were calculated. Relative and absolute level changes suggesting improvement were found in the scores across both conditions based on median and mean scores on each measure in both phases. Stable trends in improvement in scores were also observed across sessions. All scores in the intervention phase were lower compared with the baseline phase, suggesting no data overlap. Mrs P’s PHQ-9 scores reduced from 17 to 5, and her GAD-7 scores reduced from 21 to 3, suggesting reliable change.

Discussion

The results suggest that unhelpful thoughts, anxiety, and depression in DFCs may be reduced by even a time-limited CBT intervention, thus supporting the hypotheses that modifying these cognitions and supporting DFCs to reclaim pleasurable and positively reinforcing activities in life may decrease depression and anxiety. In particular, in our study, dysfunctional thoughts decreased in line with Mrs P’s anxiety and depression scores, the relationship between which has been highlighted by previous literature (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015). Since Mrs P’s scores began reducing at baseline, it is possible that the space to express her thoughts and feelings in a normalising context could have been therapeutic.

Limitations and future directions

Dementia impacts families in different ways, which limits the generalisability of the finding to other families. Similarly, the current study did not involve follow-up measurement. Future research could thus investigate the long-term effects of CBT for this population. Mrs P’s husband’s denial of his diagnosis restricted Mrs P’s engagement in between-session tasks. This also limited opportunities to conduct further baseline assessments with this client, as she was always with her husband outside of the therapy sessions. Moreover, the lack of social support during the COVID-19 lockdown may have limited the effectiveness of the CBT intervention. Lastly, although Mrs P’s scores did not reduce completely, this could be due to the impact of the degenerative nature of dementia on families.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246582300053X

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The data that support the findings of this study are also available on request from the corresponding author, L.F. The full dataset is not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the participant’s clinical data.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the client who gave consent for this piece of work to be submitted for publication. The primary author also thanks the secondary author and supervisor of the work for her guidance.

Author contributions

Lawson Falshaw: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Leah Clatworthy: Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. The client described has seen the case report in full and has given informed consent for it to be published.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.