Introduction

Cohesion plays a pivotal role in facilitating group performance in goal-oriented tasks and serves as a motivating force that encourages members to stay together (Mudrack Reference Mudrack1989). In the context of military organizations, cohesion becomes a critical factor in fostering bonds among soldiers facing adverse conditions, thereby enhancing both their endurance and military effectiveness (Oliver et al. Reference Oliver, Joan Harman, Hayes and Pandhi1999). It not only aids in overcoming collective action problems and motivating individuals to engage in challenging military group endeavors (Siebold Reference Siebold2007) but it also influences individuals’ perceptions of well-being and job satisfaction (Bliese and Halverson Reference Bliese and Halverson1996; Evans and Dion Reference Evans and Dion1991; Gully et al. Reference Gully, Devine and Whitney1995; Langfred Reference Langfred2000).

Furthermore, cohesion has been identified as a significant factor explaining the behaviors and forms observed in irregular armed groups (Hansen Reference Hansen2018; Verweijen Reference Verweijen2018). However, when military organizations, such as insurgent groups, move into postconflict contexts during peace-enabled transitions, they usually find that the conditions that previously held the group together may no longer be in place (Söderberg Kovacs Reference Söderberg Kovacs, Anna and Timothy2008).

Despite the pivotal role of ex-rebel parties in political reintegration and postconflict stability, evidence suggests that these parties often have short life spans, with many quickly becoming irrelevant or dissolving altogether (Allison Reference Allison2006; Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2016).

This article explores what motivates ex-combatants to remain as party members during the early years of transition, thereby increasing the chances of sustaining the organization over the long term. Specifically, we address the question of what factors contribute to cohesion levels within ex-rebel organizations in the postconflict context.

By examining the case of the Comunes political party, which succeeded the largest guerrilla group in Latin America, we intend to test the significance of ideology, selective incentives, and organizational dynamics in explaining former rebels’ commitment to staying united.

Cohesion in Postconflict Transitions

Cohesion can be defined as “the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs” (Carron and Brawley Reference Carron and Brawley2012, 731). In fields such as psychology, sociology, and administration, cohesiveness offers insights into group dynamics that influence the perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes of its members (Hogg and Terry Reference Hogg and Terry2000; Mullen and Cooper Reference Mullen and Copper1994). Moreover, it has attracted particular attention in military, sports, arts, politics, and managerial contexts due to its potential impact on goal-oriented task performance (Casey-Campbell and Martens Reference Casey-Campbell and Martens2009).

Historically, the concept of cohesion has suffered from a lack of precise definitions and subsequent operationalization. In the past, it has often been described simply as “attraction to the group” (Pepitone and Kleine Reference Pepitone and Kleiner1957; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Fuehrer and Childs1983; Taylor and Strassberg Reference Taylor and Strassberg1986), “the desire of members to remain in the group” (Leana Reference Leana1985; O’Reilly and Caldwell Reference O’Reilly and Caldwell1985), or “commitment to the group” (Piper et al. Reference Piper, Myriam Marrache, Richardsen and Jones1983).

More recently, a more precise approach considers cohesion to comprise both a task and a social component (Dion Reference Dion2000; Zaccaro and Lowe Reference Zaccaro and Lowe1988). Consequently, the literature often refers to them separately as task cohesion and social cohesion (Carless and de Paola Reference Carless and de Paola2000).

Military studies have largely adopted this dual approach, describing task cohesion as “commitment to the task” and social cohesion as “interpersonal attraction,” while also distinguishing cohesion from closely related concepts such as group pride, identity, morale, or trust (King Reference King2007; McCoun and Hix Reference McCoun and Hix2010). Specifically, the relevant literature has debated the relative importance of task and social cohesion in explaining performance, job satisfaction, and psychological distress (Griffith Reference Griffith2008; Oliver et al. Reference Oliver, Joan Harman, Hayes and Pandhi1999; Ozer et al. Reference Ozer, Best, Lipsey and Weiss2003).

While previous works have focused on how cohesion levels affect military organizations, including insurgencies, during wartime, postconflict transitions present a different context that influences former combatants’ willingness to remain part of their group.

The transformation of rebel movements into parties, and their active participation in politics, is a particularly impactful provision in post-Cold War peace processes (Söderberg Kovacs and Hatz Reference Söderberg Kovacs and Hatz2016).

There is an expectation that the existence of ex-rebel parties should affect postconflict institutional stability and peace consolidation in a positive manner (Blattman Reference Blattman2009; Jarstad and Sisk Reference Jarstad and Sisk2008; Mitton Reference Mitton2008). More than half of all peace processes that ended between 1989 and 2016 explicitly discussed the inclusion of rebels in politics, and more than 70 ex-rebel parties were created in that period (Manning and Smith Reference Manning and Smith2016).Footnote 1 And recent evidence supports a relation between participation of ex-rebel parties, on the one hand, and the quality and stability levels of postconflict democracies, on the other (Tuncel and Manning Reference Tuncel and Manning2022).

In the early years of transition to peace, ex-rebel parties are typically the main actors in social and economic postconflict transformations, as they serve as mediators between former war antagonists, and may potentially constitute major drivers for cementing democratic values in society as well as promoting the demilitarization of political life (Curtis and Sindre Reference Curtis and Sindre2019).

It is not uncommon in public policy to view the problem of ex-combatants’ political inclusion, and particularly that of their elites, as a security issue (Hensell and Gerdes Reference Hensell and Gerdes2017). In the short term, the inclusion of former rebel parties in government or parliamentary positions has been demonstrably helpful in reducing the chances of conflict recurrence (Marshall and Ishiyama Reference Marshall and Ishiyama2016). Likewise, failure in the effective integration of rebels into political discussions and decisionmaking processes creates a negative incentive for ex-combatants to fully commit to a permanent renunciation of the use of the violence (Berti and Gutiérrez Reference Berti2016).

Major rebel-to-party works tend to focus on how former combatants have access to office and formal seats at an institutional level, and also how they compete for further access through electoral means (Berdal and Ucko Reference Berdal and Ucko2009; Lyons Reference Lyons2005). Nevertheless, literature focusing on the concept of political reintegration has particularly explored how ex-rebel parties serve as a tangible alternative for solving the problem of political inclusiveness for both elites and rank-and-file ex-combatants (Wiegink Reference Wiegink2013).

In their role as a central piece in the political reintegration of former rebels, successful parties resulting from war-to-peace transitions should enable former combatants and their constituencies to get involved in public policy decisions at national, regional, and local levels regardless of their electoral performance (UN 2014). Thus, while short-term electoral performance creates incentives for members to either stay or leave, some rebel parties can sustain setbacks in the critical early postconflict years, while others do not (Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Huang and Sawyer2021; Manning and Smith Reference Manning and Smith2019).

Regardless of their results in the polls in the first years of transition, the former rebel party’s immediate agenda is usually to consolidate their influence on public debates, advance their internal transformation, solidify their members’ commitment to a full renunciation of violence, and cement the postconflict political system (Dudouet Reference Dudouet2012; Mitton Reference Mitton2009; Söderström Reference Söderström2011).

Even after an electoral setback, ex-rebel parties should be able to survive as long as they serve at least as participants in the electoral system, by presenting candidates, doing campaigns, and mobilizing support; as participants in elected governments at subregional and local levels; as representatives of specific social segments; or as influencers of the public agenda (Cyr Reference Cyr2016).

Given their relevance beyond potential electoral achievements, ex-combatants will value their new legal party as a vehicle to pursue their reintegration and political projects; yet, we observe how these organizations frequently reduce their presence in the public sphere, and their membership shrinks to the point of disappearance.

But the political reintegration of former rebels does not depend on the existence of a former rebel party (Alfieri Reference Alfieri2016; Söderström Reference Söderström2013). Rather, ex-combatants’ integration into the political system implies their explicit adherence to the established legal political system, either as individual citizens or as part of a collective (Söderström Reference Söderström2015).

Although the decision of rebels to transit toward democracy is likely prompted by strategic considerations, the choice to take the collective route is usually related to contexts in which conflict ended as a result of a peace accord, especially when international actors are active in the peace process itself and its implementation; when the former armed group acted internally as a party during wartime, or had a politically oriented structure; and if former rebels need to distance themselves from still-active armed groups (Manning and Smith Reference Manning and Smith2016).

Given that former combatants typically constitute the backbone of their membership, ex-rebel parties face the challenge of transforming the nature of their bond with their constituencies. Besides their essential function in postconflict zones to serve as political organizations, which may be seen a continuation of their wartime political struggle, former rebel groups need to resolve expectations that they will continue to providing basic services.

The challenges brought by this restructuring process become evident in an examination of the recent transition of former FARC guerrillas in Colombia into a legal organization, following a peace accord that put an end to their armed insurrection.

The FARC’s Transition as a Relevant Case

At the height of their military power early this century, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) controlled large swathes of territory, especially in the eastern and southern regions of the country, imposing their own rule as the de facto executive and judicial authority in many rural areas despite localized resistance from some communities (Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2017). Its founder and top commander, Manuel Marulanda, had embraced Marxism-Leninism as a guiding principle for their military plans and the organizing principle for the rebels themselves and the population under their influence. The guerrillas acted as an armed wing for the Colombian Communist Party since the 1950s, and in the 1980s they created their own independent Clandestine Communist Party.

After about half a century of guerrilla warfare, the FARC signed a peace agreement with the government in 2016, which included explicit provisions for their participation as a legal political party as holders of 10 temporary parliamentary seats.Footnote 2 A total of 6,500 guerrillas handed their arms to a UN technical mission, and about 12,000 former members, including noncombatants, were formally discharged.

Having been the oldest and largest guerrilla group in Latin America, the FARC’s transition was the most impactful in the region in the twenty-first century. Its past as a political party in arms, and the context of a negotiated transition, should in theory put the former rebels in a favorable position to build a legal political party capable of capturing votes, consolidating financial support, and enduring in the long run.

Existing literature on the transition of former FARC guerrillas to civil life have so far focused on describing how FARC’s ex-combatants perceive the reintegration process (Gluecker et al. Reference Gluecker, Correa-Chica and López-López2022; Thomson Reference Thomson2020), and the challenges of civil life (McFee and Rettberg Reference McFee and Rettberg2019; Nussio and Quishpe Reference Nussio and Camilo Quishpe2019). Two major efforts have been made to systematically describe ex-combatants’ views of their own transitional process. The first consisted of a survey reaching out to the totality of demobilized guerrillas in their cantoning areas, conducted in the early days of their disarmament in 2017. This study served as a basis for the structuring of public policy on reintegration (National University 2017). That work included only one item referring to political reintegration, in which 61 percent of respondents (5,805 individuals) expressed their interest in working with the new political party. A second survey, conducted by the official reintegration program between 2018 and 2019, covered about 90 percent of demobilized guerrillas in the process of reintegration, but political reintegration questions were absent (Arjona et al. Reference Arjona, Fergusson, Garcia, Hiller, Polo and Weintraub2020).Footnote 3 Through interviews and document analysis, researchers have also been able to monitor the performance of Comunes as a legislative body in the Colombian Congress (Rettberg and Moreno Martínez Reference Rettberg and Moreno Martínez2023).

In September 2017, the former guerrilla group constituted the FARC Party—before changing its name to Comunes in 2021—and set out to participate in regional and national elections the following year. Their structure back then resembled their wartime political apparatus, relying on escalating hierarchies from grassroot neighbor/village councils, to local, regional, and national-level decisionmaking bodies.Footnote 4 After holding an internal election, most former members of the former guerrilla group’s top-level command structure, the Central Joint Staff, were chosen to be part of the party’s new collective direction body, the National Political Council, which was led in turn by their former top guerrilla commander.Footnote 5

The new party’s statutes combined explicit claims to defend a set of values expected for contemporary democratic parties, such as principles of participation, equality, gender parity, transparency, pluralism, and morality, with an adherence to the core decisionmaking procedures of their former Marxist-Leninist incarnation, namely principles of democratic centralism, collective direction with individual responsibility, control and planning, and criticism and self-criticism. As a main ideological orientation, the statutes declared the party’s main stances as drawing from “critical and libertarian thought … formulated by the FARC-EP since its foundational moment, especially by our founders Manuel Marulanda Vélez and Jacobo Arenas.” They committed “to overcome the current capitalist social order in Colombia,” as well as to “the construction of a new political economy that guarantees the material realization of human rights, nondestructive or nonpredatory relationships with nature and the environment, a new ethic, and social relations of cooperation, brotherhood, and solidarity.”Footnote 6

As anticipated in the transition from war to democracy, the political party faced significant challenges right from the outset, both in terms of maintaining its cohesion levels and ensuring its long-term survival. The high levels of political polarization that characterized both the peace process and the subsequent implementation of the final accord posed obstacles to the reintegration of the FARC into civilian life and democracy (Laengle et al. Reference Laengle, Loyola and Tobón-Orozco2020).

This context was further complicated by the emergence of new patterns of violence following the FARC’s demobilization. While the emergence of armed dissidents and spoilers in postconflict settings is to be expected (Nilsson and Söderberg Kovacs Reference Nilsson and Söderberg Kovacs2011), the FARC’s demobilization and reintegration took place against a backdrop of targeted killings and threats against local leaders and ex-combatants, as well as the territorial expansion of drug-related illegal groups (Albarracín et al. Reference Albarracín, Corredor-Garcia, Milanese, Valencia and Wolff2023). Remarkably, these challenges did not derail the former guerrillas’ transition.

As for electoral results, in March 2018, the former FARC’s party received about 50,000 votes for the Senate—0.36 percent of total votes—and 30,000 for the House of Representatives—0.24 percent. Its presidential candidate, their former top commander, dropped out of the race two months before the election. This development was followed by a major split from a faction that felt inadequately represented in the power structure within the party.Footnote 7

To navigate these challenging circumstances, the party underwent a transformation, rebranding itself as Comunes to distance itself from its former military identity. Subsequently, it aligned with a left-wing coalition movement that secured a majority of seats in Congress in 2022. The party’s ability to retain ten parliamentary seats for a second term that year, as stipulated in the peace agreement, provided it with some breathing room for internal reevaluation.

Here we present the first quantitative study, to our knowledge, focusing on ex-FARC rebels who are now officially party members of Comunes. We aimed to analyze their views on their political reintegration process, and particularly to explore explanatory factors of their observed cohesion levels.

Determinants of Ex-Rebel Party Cohesion

In broad terms, individuals formally join parties due to ideological motivations and the presence of selective incentives (Heidar Reference Heidar, Richard and William2006; Panebianco and Trinidad Reference Panebianco and Trinidad1990). In the case of ex-rebel parties, success in maintaining or growing their membership in the early transition stages depends on their capacity to both keep their appeal to existing constituencies and attract new audiences. Since early membership is dominated by ex-combatants and civilian supporters from wartime, their perception of how the new organization functions after transition becomes of special relevance.

A combination of factors, including strong leadership, ideological commitment, a coercive military structure, and the selective incentives provided to individual guerrillas in terms of finances and security, allowed the FARC to maintain its activity for more than six decades of armed rebellion (Nussio and Ugarriza Reference Nussio and Ugarriza2021). Arguably, all of these elements faced significant challenges once the war ended, and especially following the death of the FARC’s founder and top commander. In the absence of a military apparatus, one would anticipate that ideology and selective incentives would become the primary sources of cohesion among former rebels in the postconflict context.

In the following section, we describe how ideology, selective incentives, and organizational dynamics relating to their transition from armed group to political party may help to explain the ex-rebel organization’s ability to retain their core membership and guarantee its long-term survival.

Ideology

Drawing frequently from the Colombian case as a reference point, scholars have debated the significance of ideology in contemporary armed conflicts (Schubiger and Zelina Reference Schubiger and Zelina2017). Although patterns of criminality have been historically evident, ideology retains both instrumental and normative value for insurgent organizations (Gutiérrez Sanín and Wood Reference Gutiérrez Sanín and Wood2014). This value is reflected in the discourse and behavior of combatants, as exemplified in the case of FARC guerrillas (Ugarriza and Craig Reference Ugarriza and Craig2013).

In war, ideology provides not only a source of legitimization, but also a blueprint for how to behave at the tactical and strategic levels, particularly among Marxist-Leninist guerrillas (Ugarriza Reference Ugarriza2009). Far from becoming irrelevant after war, ideology is key as major source of cohesion once their task-oriented role within the armed apparatus ceases, and the social bonds derived from living and surviving together are weakened (McCoun et al. Reference McCoun, Kier and Belkin2006). Even though some ex-rebel parties manage to continue relying on armed structures that keep militants adhered to military and bureaucratic tasks (Allison Reference Allison2016), renunciation of war itself affects their cohesion levels and causes internal contradictions (Berti Reference Berti2011).

Ideology mainly serves as a cornerstone of the group’s identity, which in turn affects the nature of its relationship with the civilian population at large, as well as with interest groups and institutions. In the former FARC’s example, governance in rural areas and their relationship with communities were effectively guided by ideological principles (Arjona et al. Reference Arjona, Kasfir and Mamipilly2015). Such principles are later utilized when the ex-rebel parties legally take office (Salih Reference Salih2003; Wilson Reference Wilson2020), particularly when controversial policies need to be defended (Aalen Reference Aalen2019).

While an ex-rebel party’s capacity to demonstrate a reasonable degree of ideological continuity can potentially yield benefits in terms of favorable public opinion (Katz and Crotty Reference Katz and Crotty2006), transitioning from war to democracy implies resolving the internal tension between radicalism and moderation in fundamental issues, such as the proposed role of the state in social and economic affairs (Ishiyama and Batta Reference Ishiyama and Batta2011; Wilson Reference Wilson2020).

In this context, effective participation in the political system favors internal deradicalization (Berti Reference Berti2019). This usually entails a process of rebranding or adaptation that may either alienate segments of their core constituency or prompt authoritarian action from party elites as a way to suppress potential dissidence (Burihabwa and Curtis Reference Burihabwa and Curtis2019).

Intraparty ideological tensions constitute a permanent trait in all ex-rebel parties. In cases of electoral failure, it is precisely the most ideologized members who tend to stay (Söderberg Kovacs Reference Söderberg Kovacs2021), although success with a moderate discourse does not necessarily eradicate the most dogmatic segments (Sprenkels Reference Sprenkels2019).

We expect cohesion levels to be affected by the presence of functioning mechanisms capable of managing internal contradictions between the party’s line and its members’ own stances on fundamental ideological issues, such as positioning on the left–right spectrum, nationalistic or religious core values, and social and economic policy (Hellinger and Smilde Reference Hellinger and Smilde2010). We thus hypothesize that party members with higher levels of cohesion should in turn display stronger levels of ideological commitment to the party line (H1).

Selective Incentives

In the transition from war to democracy, former members of armed organizations are confronted with the decision of pursuing their political reintegration either as party members or as individual citizens. Thus, the ex-rebel party is not indispensable for their particular transitions.

One way of understanding how selective incentives affect cohesion in former rebel groups is the party’s ability to present itself as a proper substitute for war (Themnér Reference Themnér2011). In wartime, successful armed groups keep their unity by means of economic incentives (Humphreys and Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008), including sometimes opportunities to loot (Collier and Hoeffler Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004), but also by offering security levels that are hard to achieve outside the group (Kalyvas and Kocher Reference Kalyvas and Adam Kocher2007). Once in civil life, one major centripetal force for individuals to remain as members are their perceptions of the party as a proper vehicle to vindicate their demands for security, economic means, and social recognition and validation, and also to advance their own agendas as an interest group (Wiegink Reference Wiegink2013).

In several Asian and African instances, possessing financial resources to sustain armed structures and provide security services has been coupled with the capacity to deliver essential services to their members, including healthcare, education, and employment. In these cases, ex-rebel parties exercise control over both private and state assets to fulfill these needs while simultaneously generating revenue through their existing civilian business networks, as exemplified in Mozambique (Pearce Reference Pearce2020), Burundi (Wittig Reference Wittig2016), Zimbabwe (Liu Reference Liu2022), Nepal (von Einsiedel et al. Reference von Einsiedel, Malone and Pradhan2012), Afghanistan (Maley Reference Maley2018), and Iraq (Moon Reference Moon2009).

Conversely, in European and Latin American contexts, most rank-and-file ex-combatants have had to depend on reintegration programs for basic service provision, often incorporated into peace agendas. Former rebels are compelled to disengage from illegal markets and activities that generated income during wartime (UN 2014), even when incentives to insert themselves into illegal markets persist (Kaplan and Nussio Reference Kaplan and Nussio2018).

In El Salvador, ex-rebels’ civilian support networks played a crucial role in securing their party’s long-term financial stability while gradually increasing their access to state resources, as stipulated in the peace accords and facilitated by electoral progress (Wood Reference Wood2003). Such robust civilian support was absent in the Guatemalan case, where financial challenges significantly impacted Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca, URNG) activities from the late 1990s (Allison Reference Allison2016). Predictably, structural changes in how groups provide services to their rank-and-file constituencies often lead to growing sentiments of resentment among disgruntled ex-combatants.

The fact that social and economic life competes with political commitment also pulls former combatants away from their former organization (Söderström Reference Söderström2016). In civil life, if the party does not constitute the major or sole provider of economic means of survival, social networks, and emotional support, building such support systems while pursuing a political life comes at an opportunity cost (Scarrow Reference Scarrow2015).

Related to that, transitions are conducted in unstable contexts, usually under threat of residual or even persistent violence (de Zeeuw Reference de Zeeuw2007). Recognition of the costs of political action under adverse circumstances can be a powerful deterrent for ex-combatants’ public participation.

In order to remain an attractive option to its core wartime constituency, the ex-rebel party must usually compromise its broader interest in appealing to potential voters at large to meet its need to respond to the narrower yet urgent agenda of its core members. As a result, by representing a specific social segment, parties must sometimes sacrifice votes in the name of keeping their internal cohesion (Sindre Reference Sindre2016a).

We therefore expect to find higher cohesion levels among members who believe the party properly represents their own personal interests (H2), report interest in personally engaging in elections as campaigners or candidates (H3), and observe favorable and secure conditions for the party’s political participation (H4).

Organizational Dynamics

While it is reasonable to assume that internal dynamics are key to understanding why some parties succeed in remaining relevant over time while others disappear, ex-rebel parties might have a particular vulnerability in that regard (Sindre and Söderström Reference Sindre and Söderström2016).

The endurance of ex-rebel parties heavily depends on their ability to evolve the nature of their relations with the civil population and their constituencies after acquiring legal status (Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Rakner and Aagedal Skage2016). Negative or null transformations within the party may put it at odds with democratic values, thwarting the positive effect the ex-rebel party is expected to exert on the quality of the political system (Wittig Reference Wittig2016).

Some types of ex-rebel organization might be more inclined to embrace democratic procedures than others. Given the military-driven nature of their former structures and hierarchies, many ex-rebel parties are frequently expected to behave as “militant, hierarchical, sectarian, and internally undemocratic” organizations (Manning Reference Manning2007; Söderström Reference Söderström2016). Sindre (Reference Sindre2016b) suggests that armed organizations that were more dependent on regional structures and had relatively lower levels of centralization tend to breed parties dominated by elites.

The political context in which former rebels compete also seems to affect the type of rebel organization emerging from the political reintegration process. In Nepal, for instance, the presence of major electoral competitors may help to explain why the former Marxist guerrillas opted to recruit moderate candidates with a broader appeal rather than merely former rebel elites, opening themselves to more flexible and compromising stances (Ishiyama and Marshall Reference Ishiyama and Marshall2015). Conversely, the absence of such competitors in Rwanda could have incentivized the former rebels to conduct a superficial transformation in which their discourse seemed to embrace democratic values, while their internal and governmental practices exhibited an authoritarian nature characteristic of their military past (Rufyikiri Reference Rufyikiri2017).

Besides electoral contestation, Lyons (Reference Lyons2016a, Reference Lyons2016b) also points to how the way in which conflict ends also matters. By examining African cases, the author claims that rebels who have won the war tend to become authoritarian parties, keeping their internal structures and ways of approaching civilians fundamentally unchanged. Victory, therefore, minimizes the incentives to perform internal revisions. Conversely, transitions derived from negotiated agreements should more likely present incentives for change.

In contexts of electoral competition, if a successful transition from war to democracy implies an open embracing of democratic procedures, we should then expect party members with high levels of cohesion to also believe that their party has higher levels of internal democracy (H5), and inclusion (H6).

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants and Procedures

From 2017 to 2020, after being granted permission by former FARC commanders in charge, we visited the demobilization zones of former FARC guerrillas. There, former combatants had just began their reintegration process into civilian life,Footnote 8 after completing a UN-supervised disarmament process that same year. Aided by former fighters residing in each zone, we made sure we covered all major regions of the country,Footnote 9 so that we could create a sample reflecting the cultural and geographical variance of the former guerrillas. Given that top and mid-rank commanders had a differentiated reintegration process, we explicitly opted to leave them out and focus our sample on the rank and file. Since most guerrillas demobilized in places near to their former zones of military operations, we also could reasonably reach members coming from all major FARC structures.Footnote 10 A total of 393 ex-guerrillas agreed to be part of our pool, which reflected in general terms their regional membership during wartime, as well as their education, age, and gender profiles. Of these, 30 percent had fought in the guerrilla group’s eastern bloc, 11 percent in the southern bloc, 7 percent in Magdalena Medio, 5 percent in the western bloc, 3 percent in the northwestern bloc, 3 percent in the central bloc, and 13 percent in the northern bloc.Footnote 11 The average participant in our pool was 39 years old, had 17 years of wartime experience, and had 10 years of formal education (close to high-school graduate level). Forty-two percent of participants were women, 70 percent declared themselves to have been war victims, 20 percent had spent time in prison as insurgents, and half of those were released as a result of the peace process.

Former guerrillas organized a series of face-to-face meetings with residents in the reintegration zones to brief them on the nature of our research. We obtained explicit permission from the Comunes leadership, and we utilized consent forms that explicitly guaranteed anonymity to ensure a high level of voluntary participation. Subsequently, our field assistants made additional efforts to engage interested participants who were unable to attend the initial meetings.

We are aware of a potential lack of representativeness in our sample. Ex-guerrillas who died in the course of the conflict and those who deserted are clearly not included in our study. We can only guess, at best, that the combatants represented here were exposed to more or less the same kind of risks as those not represented, and might account for the latter. Inevitably, interpretations of our results need to be assessed with these limitations in mind.

Measures

We aimed to analyze to what extent ideology, selective incentives, and organizational dynamics could help to explain the variance in cohesion levels among Comunes party members.

Participants were given a questionnaire of basic demographic information (e.g., age, gender, education level, wartime years, and former military unit). Two additional items were asked to qualify their war experience: whether they considered themselves to be conflict victims—and of which side—and whether they had been imprisoned by the state authorities in the past.

Empirical studies on cohesion have often focused on examining individuals within groups rather than assessing the cohesion of the groups themselves (Mudrack Reference Mudrack1989). Consequently, efforts to operationalize cohesion based on individual-level definitions have relied on aggregated individual measures, such as members’ duration of membership, intention to remain in the group, identification with the group, and interpersonal ties, among others (Friedkin Reference Friedkin2004).

Carron and Brawley (Reference Carron and Brawley2012) have proposed a multidimensional model that encompasses both social and task cohesion, as well as individual and group-level dimensions. Subsequently, they introduced a specific operationalization of their model known as the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ).

The GEQ adheres to a widely used methodological approach for measuring cohesion in which individuals serve as sources of data about the collective (Lindsley et al. Reference Lindsley, Brass and Thomas1995). It consists of an 18-item battery that aims to assess cohesion levels in groups in terms of “closeness, similarity, and bonding” (Carron and Brawley Reference Carron and Brawley2000, 90). Their conceptual proposal is understanding cohesion as a multidimensional construct with four major dimensions: individual attractions to the group related to socialization (ATGS), individual attractions to the group related to the organization’s tasks (ATGT), group integration at the social level (GIS), and group integration for the task (GIT). When applying the GEQ, the authors suggest adapting the wording of items to better fit the nature of the group (i.e., club, group, team), the flow of activities (i.e., seasonal events, daily activities), and the specific context (i.e., geographical or cultural specificities), while ensuring conceptual clarity of what is being measured by each specific item. A transcription of the applied questionnaire is included in the supplementary material.Footnote 12

This instrument has been employed in various contexts, including work, arts, and sports (Dyce and Cornell Reference Dyce and Cornell1996; Mullen and Cooper Reference Mullen and Copper1994; Zaccaro Reference Zaccaro1991). Of particular relevance to our study, a confirmatory analysis has demonstrated the validity of the four-factor model outlined by the GEQ in a sample of military personnel (Ahronson and Cameron Reference Ahronson and Cameron2007).

For ideological measures, we relied on two survey instruments that have previously been used in studies of the explicit ideological attitudes of ex-combatants in Colombia. One of these instruments consists of six interspersed Likert-type items that measure attitudes toward leftist groups, and six more toward rightist groups.Footnote 13 In each case, half of the sentences were worded in positive terms and the other half in a more negative tone. Items aimed to capture biases in terms of who is more to blame for political, economic, social, and security problems in the country (leftists and/or rightists), and who is contributing the most to solving them. Items were aggregated to estimate scores on a scale from −6 to 6, creating the attitudes toward left and attitudes toward right variables. The second instrument consisted of an ideological self-identification scale, where participants were asked to place themselves on a range from 1 to 10: the lower the mark on the scale, the closer their affinity to the political left, and vice versa. The scores are reflected in our ideology score variable.

We included three measures as potential proxies for the presence of selective incentives, either positive or negative, for participants to continue their political reintegration as party members. Our first measure consists of a battery of five Likert-type items aimed at gauging to what extent participants feel the party represents their own agenda, stances, and preferences at the individual level. Items asked about the strength of their self-identification with the party’s positions, their willingness to overcome their potential divergences with the party line, their own appreciation of the party’s distinctive identity and values when compared to other parties, and the positive and negative emotions the party is capable of evoking in them. These items are then aggregated in our self-identification score.

Our second selective incentives measure captures the participant’s perceptions of the potential costs of remaining in-party. After presenting them with a response scale from 1 to 10, we asked participants to indicate how favorable or unfavorable they perceived the conditions to be for the party’s participation in politics. As a third measure, we asked participants about their own interest in being part of a political campaign, or being party candidates themselves, as a way of gauging their electoral incentives. These two items are aggregated into our electoral interest variable.

In the case of organizational dynamics, we explored the participant’s perceptions of the party’s internal democracy and levels of inclusion. One battery of seven Likert-type questions asked about decisionmaking procedures within the party, in terms of whether stances were decided just by the elite; if the party leader was too powerful; if candidates were selected in a democratic manner; if women and ethnic minorities had the same access to positions of power as men and nonminorities; and to what extent public opinion affected intraparty decisions. A second battery asked participants to what extent different constituents took part in the party’s decisions, including national and regional leaders, affiliates and supporters, parliamentary members, voters, and external segments such as mass media, public opinion, other groups of interest, and the government.Footnote 14

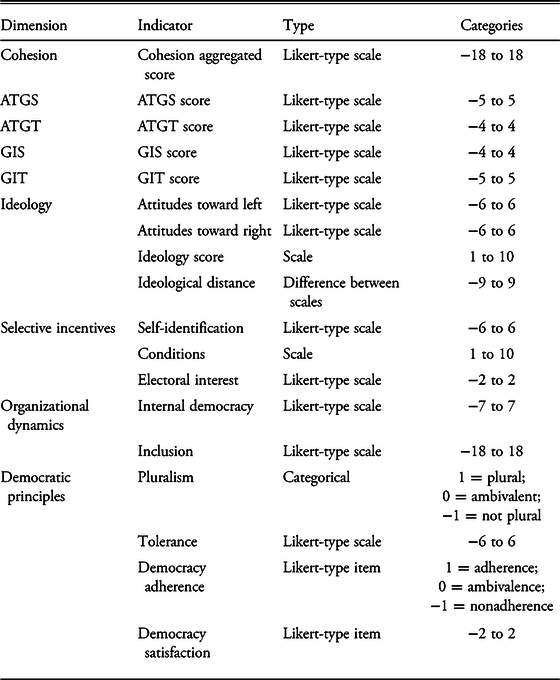

We also added a series of items to grasp participants’ stances on core democratic principles, which serve as control for our main analysis. In particular, we asked them about their levels of pluralism (their stated appreciation, disfavor, or indifference toward political differences); tolerance (as an aggregated measure of six Likert-type items); explicit democracy adherence as a preferred form of government; and their self-reported magnitude of democracy satisfaction (see original items in the supplementary material).

In table 1, we present a summary of the variables and their operationalization.

Table 1. Operationalization of Variables

Data Analysis

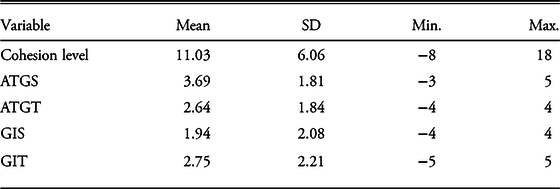

In table 2, we observe that the overall mean cohesion level within our sample is 11.03, which lies in the second quartile of the GEQ scale scores. This is also the case for all four disaggregated dimensions (see table 1 for score ranges).

Table 2. Cohesion Levels by Dimension

A preliminary analysis of potential confounding variables for our proposed hypotheses lets us establish that cohesion scores are significantly correlated with whether the participant reported that they had been a victim of a guerrilla group—and less correlated with their having been a victim of state or paramilitary forces, or having not been victimized at all (r = −0.176, p = 0.000). Not surprisingly, those who felt they were victims of such groups (i.e., their own, or fellow insurgent organizations) tended to show lower cohesion scores with the ex-rebel party on average (scoring 7 against 11 for nonvictims). This latter segment of participants corresponds to 6.5 percent of the total sample. We did not find significant correlations of cohesion levels with variables of age, gender, education, geography, combat experience, years spent at war, or being an ex-prisoner.

When comparing cohesion levels with our proposed covariates, we report a weak significant and positive correlation with tolerance (r = 0.132, p = 0.012); we also find that participants adherent to democracy have a significantly higher cohesion score average than the nonadherent or ambivalent groups (ANOVA F = 3.20, p = 0.042; adherents’ score = 11.5; nonadherents = 9.4; ambivalent = 10.7).

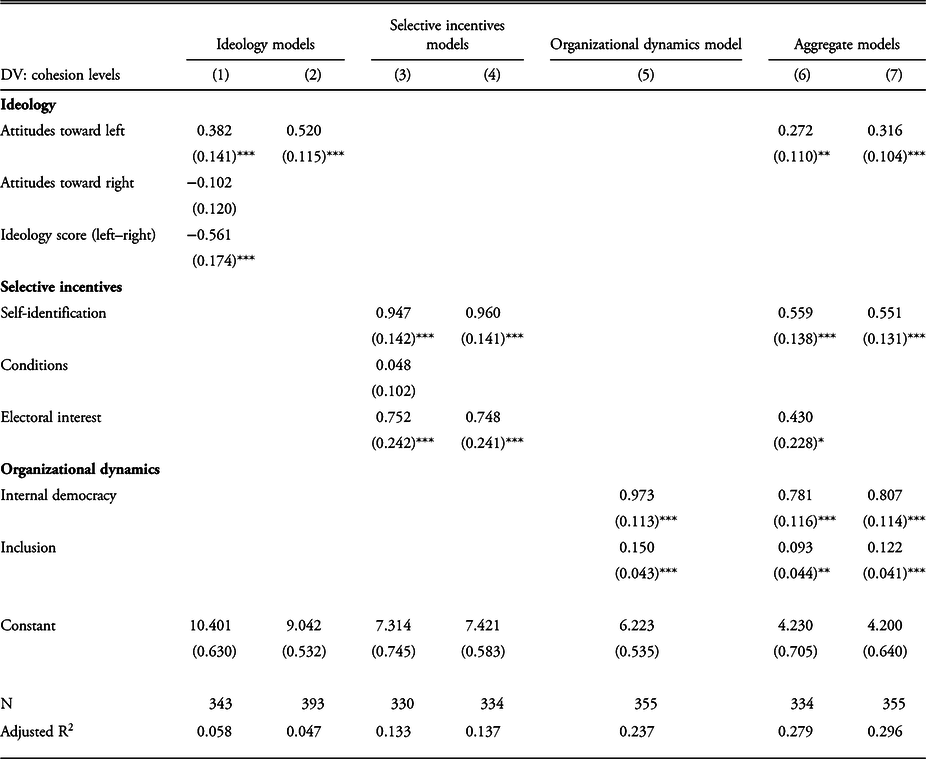

In table 3, we proceed to test our hypotheses. On the second column from the left, we present a saturated model including our three variables related to ideology. Although two of them are significantly related to cohesion, the amount of variance they explain is small, as shown by the adjusted R2. The third column shows how the “attitudes toward the left” variable carries most of the model’s predictive power.

Table 3. Potential Predictors of Cohesion Levels (OLS)

**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Models 3 and 4 test the relevance of our selective incentive variables. These models double the predictive power of those centered around ideology. Here, individual self-identification with the party and personal interest in participating in electoral politics are positively correlated with higher cohesion levels. This is not the case for their perception of how favorable or unfavorable conditions are for the party’s performance.

Our fifth model presents the variables related to organizational dynamics. Perceptions of high democracy and inclusion levels within the party positively help to predict cohesion, almost doubling the power shown by the selective incentives models. Our last two models, 6 and 7, present iterations that include variables from the three dimensions being studied. There we observe that our best-fitting model (7) combines elements from all three dimensions.

Our data arguably adds weight to most of our stated hypotheses, given that higher cohesion levels seem to be predicated on ideological commitment (H1), individual representativeness (H2), an individual’s electoral interests (H4), and higher perceptions of internal democracy (H5) and inclusion mechanisms (H6). Comparison among models, however, also points to the fact that even if all dimensions are relevant, organizational dynamics are what seem to better explain cohesion levels in a parsimonious way.

Discussion

Analysis of postconflict political reintegration at meso (e.g., party) and individual levels lets us identify what happens within ex-rebel-based structures, beyond what it is externally observable in terms of their public engagement.

The positive relationship we observed between ideological measures and cohesion scores, as stated in our first hypothesis, not only aligns with existing literature emphasizing the importance of shared beliefs in armed groups but also suggests that these beliefs carry over into nonarmed political contexts.

Our second hypothesis posited that the party’s ability to deliver for its core membership, as it did during wartime, would be reflected in cohesion levels. The relation between more negative perceptions and lower cohesion levels illustrates the internal tension that arises from attempting to simultaneously push a public agenda to remain politically relevant and advocate as an intermediary between ex-combatants and the state. Without substantial financial autonomy, Comunes struggled to resolve the dilemma of serving a core constituency while allocating limited efforts and resources to expand it.

In line with our third hypothesis, we found that a core segment of those willing to serve as candidates and provide campaign support tended to exhibit higher cohesion levels. In modern political parties, those formally involved in political organizations engage in voluntary activities, provide financial support, participate in internal discussions, convey the party’s ideas to the broader public, and help to legitimize the party’s positions. Future studies may explore how the less cohesive segment of rebel organizations can still play a relevant role in the party’s survival and performance.

Our fourth hypothesis relates to the connection between cohesion and the ex-rebel party’s ability to address the security dilemmas of its members. Armed groups can attract recruits by making it more appealing to be inside the group than outside, under the group’s protection. But our results suggest that perceptions of insecurity weaken ex-combatants’ motivation to remain within the group. The tragic history of political genocide against former leftists and FARC sympathizers in the 1980s may contribute to their sense of danger. We observe that individual perceptions of insecurity carry weight in the postconflict context, and distancing themselves from the group may offer ex-combatants a better solution to their dilemma in the new context.

Our last two hypotheses suggested that two pillars of modern parties—inclusion and internal democracy—should influence cohesion levels. The positive relationships we found in both cases suggest that former rebels anticipate a revision of the rigid hierarchical command structure from wartime and expect opportunities to have their voices heard. The failure to carry out these two significant transformations appears to be the most crucial factor affecting ex-combatants’ incentives to stay. An often overlooked aspect of most rebel-to-party transitions is that, contrary to what demobilization is theoretically supposed to achieve, power structures and chains of command often persist after the war. The translation of military leadership to a postconflict structure requires a legitimizing process that former commanders may either fear or take for granted. Incentives to continue submitting to authority may not be present once the transition to civilian life has occurred.

The FARC is not the only rebel movement turned legal party that has suffered hardships in the process of transforming its organizational dynamics, and the way it interacts with people at large, to remain viable as a political force. The Guatemalan case, with the URNG, precisely illustrates how difficult relations with the population, internal division, electoral setbacks, and lack of capacity to fulfill the demands of their own ex-combatants affected their ability to remain relevant.

We cannot, however, attribute the survival of ex-rebel parties merely to their cohesion levels, and comparative studies between more and less successful cases might therefore provide new insights.

Two potential factors seem prominent: electoral performance, and the presence of either favorable or unfavorable external conditions for participation. We still do not know why some parties deal better with electoral setbacks than others. Successful parties in Rwanda, El Salvador, and Lebanon did not deal with major threats to their survival after going to the ballot, and secured significant support from voters. But more interestingly, some parties endured electoral setbacks, which forced them to overhaul their structures and open themselves to alliances with other parties and wider segments of society. This was the case for the URNG, which joined the Maiz and Frente Nacional coalitions—and now for the FARC party, which became Comunes and joined a broad government coalition in 2022. In these cases, the parties have continued being a major vehicle for ex-combatants’ political reintegration and for the mobilization of former ex-combatants and their constituencies.

As for contextual factors, we must consider again the effects of persistent systematic violence, as well as adverse electoral systems. The former does not seem to be a satisfactory explanatory factor, as most, if not all, postconflict settings are affected by residual and even systematic levels of violence, although magnitudes and modalities surely vary. As for the latter, the success of rebel parties is usually accompanied by major reforms to the political system, but the causal relationship between the presence or absence of this factor and the performance of other ex-rebel parties remains to be described.

The significance of internal dynamics provides a potentially more effective avenue for enhancing the long-term sustainability of ex-rebel organizations, thereby fostering positive effects on peace and stability. However, it is equally crucial to reevaluate the pressures stemming from political and material expectations. While leadership style and internal democratic processes remain relevant, modern parties are increasingly shifting their focus away from formal membership toward mobilization capabilities.

This research suggests that a more carefully planned transformation, focusing on internal democracy, should be prioritized to facilitate collective political reintegration. Yet, it may be beneficial to reconsider both the role and the expectations placed on ex-rebel parties and what they should strive to achieve. Such a redefinition could enable them to serve as a positive force, particularly during the early and most vulnerable years of the postconflict period.

Acknowledgments

This article builds upon data collected under Project MinCiencias 495-2020. Research procedures were approved by Del Rosario University’s Research Ethics Committee (Minute DVO005-063-CS048, February 8 2018).

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2023.37. A replication dataset is also available.