1. INTRODUCTION

In Modern French, there is variation between two adverbials that express the meaning ‘again’, and which formally only differ in their preposition: à nouveau ‘lit. to new’ and de nouveau ‘lit. of new’ (1).

While dictionaries frequently list the two adverbials as synonymous, the scarce linguistic literature on this topic has pointed out possible differences in their use. In particular, the Académie française maintains that the adverbials express different types of iteration: whereas de nouveau is used for unmarked repetition, à nouveau could be paraphrased as ‘in a completely different manner’, as in example (2).

This proposed pattern is surprising in the light of the comparative and typological literature on ‘again’ expressions, which establish a fundamental metonymy between repetitive readings (an event is repeated) and restitutive readings (a state is restored) (e.g., Wälchli, Reference Wälchli2006). From this perspective, the presence of restitutive readings would be expected. Indeed, both à nouveau and de nouveau can assume such restitutive readings (3).Footnote 1

Apart from Grevisse and Goosse (2008) and a qualitatively-minded paper by Camus (Reference Camus1992), no empirical data regarding the opposition between á nouveau and de nouveau have been adduced, and there is a complete lack of quantitative analyses on this phenomenon. The present paper aims at filling this lacuna in French linguistics. By combining data from a perception experiment and corpus data from spoken and written French, the analysis demonstrates that the opposition between à nouveau and de nouveau is at least to some extent governed by the difference between repetitive and restitutive readings, in that the use of à nouveau is more likely in contexts typical of repetitive readings, whereas the use of de nouveau is more likely in contexts typical of restitutive readings. Due to its status as the innovative variant, which is gradually displacing de nouveau, the use of à nouveau is found to be more specialized. In contrast, de nouveau can be used in a wider range of contexts; for instance, it is more likely to be used for discourse-connective functions that might derive from a historical pragmaticalization process. Finally, the analysis also shows a difference between à nouveau and de nouveau in terms of the spoken/written dimension.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 describes previous research, introduces the hypotheses studied in this paper and identifies contextual predictors of the repetitive/restitutive opposition. Section 3 introduces the corpus data and describes the operationalization of the predictor variables. Section 4 summarizes the results from the questionnaire study, which serve to confirm the relevance of these contextual predictors for the description of the repetitive/restitutive opposition. In Section 5, these contextual predictors are then used to analyze the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau. The article closes with a discussion of the relevance of these results in Section 6.

2. Á/DE NOUVEAU AND THE REPETITIVE/RESTITUTIVE DISTINCTION

This section summarizes the results from previous research, establishes the working hypothesis that the alternation between à and de nouveau is governed by the difference between repetitive and restitutive readings as well as register and the difference between spoken and written language (Section 2.1), and spells out the predictions generated by these hypotheses (Section 2.2).

2.1 Previous studies and hypotheses of this study

French iterative expressions form a complex system and can have different readings (repetitive, frequentative, habitual etc., see Gosselin, Reference Gosselin, Gosselin, Mathet, Enjalbert and Becher2013, pp. 25–28). Whereas repetitive iteration can be paraphrased as “a process is repeated at least once”, frequentative and habitual iteration are unspecified as to the number of times the process is repeated. ‘Again’ adverbials such as à nouveau and de nouveau are clearly instances of repetitive iteration, where the eventuality is repeated exactly once.Footnote 2 Gosselin (Reference Gosselin, Gosselin, Mathet, Enjalbert and Becher2013: 28–29) additionally distinguishes between non-presuppositional and presuppositional iteration. ‘Again’ adverbials and other repetitive expressions such as X fois (‘X times’) differ in that whereas a sentence such as (4a) is used to assert that the event happened several times, (4b) only asserts the repetition of the event as such, thereby triggering a presupposition that the state-of-affairs in question has been instantiated previously. This difference can easily be demonstrated by considering the effect of negating the proposition; in (5b), the negation has scope over the repetition, whereas the presupposition that Jeanne went to school at some point in the past is not affected. In other words, (5b) is not compatible with a possible world in which Jean did not go to school previously. In contrast, the adverbial trois fois is not a presupposition trigger. Consequently, the use of (5a) is compatible with a possible world in which Jean did not go to school at all.Footnote 3

In addition to à nouveau and de nouveau, Gosselin (Reference Gosselin, Gosselin, Mathet, Enjalbert and Becher2013: 28) lists the following expressions of presuppositional repetitive iteration: the prefix re-, the adverbs encore ‘again, yet’ and déjà ‘already’, and the adverbials une fois de plus ‘another time’, pour la troisième fois ‘for the third time’ etc.

While presuppositional repetitive expressions such as re- (Mok, Reference Mok and Van Alkemade1980; Amiot, Reference Amiot, Lagae, Carlier and Benninger2002; Jalenques, Reference Jalenques2002; Apothéloz, Reference Apothéloz2005; Apothéloz, Reference Apothéloz2007; Mascherin, Reference Mascherin2007; Vatrican, Reference Vatrican, Ballestero de Celis and García-Márkina2018; Lauwers, Van den Heede and Tobback, Reference Lauwers, Van den Heede and Tobback2019) and X fois (Blanche-Benveniste, Reference Blanche-Benveniste1998; Molendijk, Reference Molendijk, Bok-Bennema, De Jonge, Kampers-Manhe and Molendijk2001; Theissen, Reference Theissen2011) have been studied in detail, the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau has not received much attention. Authors frequently treat the two adverbials as interchangeable expressions. For instance, both Gosselin (Reference Gosselin, Gosselin, Mathet, Enjalbert and Becher2013: 28) and Benazzo and Andorno (Reference Benazzo, Andorno, Howard and Leclercq2017), a study on the acquisition of iterative expressions in L2 French, collapse à and de nouveau, which would seem to imply that the two adverbials are considered synonyms.

The dictionary of the Académie française claims that à nouveau can be paraphrased as ‘a second time and in a different manner’, whereas de nouveau simply means ‘another time’ (https://www.dictionnaire-academie.fr/article/DNP0748, retrieved 14 April 2020). They consequently argue that their sentence in (6) is wrong, in that à nouveau should be used. From this perspective, both à nouveau and de nouveau would express repetitive meanings, the sole difference being that à nouveau licenses the further presupposition that while the repeated event has led to the same outcome, the event itself was realized in a different manner.

Example (6) seems quite artificial in Modern French. Grevisse and Goose (2008: 1263), in their corpus of literary texts, fail to find evidence for the relevance of the difference between modified and simple repetition readings for the opposition between the two adverbials, and note that “[l]’usage des auteurs n’a pas suivi cette distinction artificielle”.

Indeed, linguistic research on ‘again’ expressions does not specifically address such modified repetition readings and instead typically analyzes ‘again’ adverbials in terms of repetitive and restitutive readings (Kamp and Rossdeutscher, Reference Kamp and Rossdeutscher1994, p. 191; von Stechow, Reference von Stechow1996; Beck and Snyder, Reference Beck, Snyder and Sternefeld2001; Fabricius-Hansen, Reference Fabricius-Hansen, Fery and Sternefeld2001; Wälchli, Reference Wälchli2006; Tovena and Donazzan, Reference Tovena and Donazzan2008). As already mentioned in the discussion of the examples in (4), in the repetitive reading, ‘again’ denotes that the state-of-affairs described by the clause is instantiated for what is at least the second time. In contrast, in a restitutive reading, ‘again’ asserts that a referent acquires a property for what is at least the second time. Usually, this reading involves a process whose direction runs counter to that of a previous process undergone by the referent, such that the referent is returned to the previous state. This previous state is frequently viewed as “normal” or “default”.

Consider, for instance, example (7) from actual corpus data. This example is ambiguous between a repetitive reading (‘DIY stores will open again’) and a restitutive reading (‘DIY stores will be open again’). The repetitive reading could be paraphrased as ‘the event of opening is repeated’, whereas the restitutive reading could paraphrased as ‘the state of being open is repeated’. In other words, the restitutive reading denotes not the repetition of an event, but the restoration of a state that previously held for the subject les magasins de bricolage.

Repetitive and restitutive readings differ in terms of their presuppositional structures. Thus, in the restitutive reading, there is a presupposition that the referent has been in that state previously. For instance, in their restitutive readings, example (8) presupposes that the Parisian teachers have been on strike before and example (9) presupposes that the domestic price has been strictly aligned with the global price before. Note that these interpretations also seem to imply the normality of this state (e.g., Parisian teachers are expected to be on strike).Footnote 4

In restitutive readings, there is no presupposition that the specific process by which the property is acquired has been instantiated before. For instance, in (9) the domestic and global prices could have been aligned right from the start. Crucially however, the restitutive reading entails that a specific previous process, situated in time between the original state and the resultant state, has led to the change of state in the referent (cf. Rosemeyer Reference Rosemeyer2016). In (9), the alignment of the domestic and the global prices is due to a previous process that caused the resultant state, namely an alignment process.Footnote 5

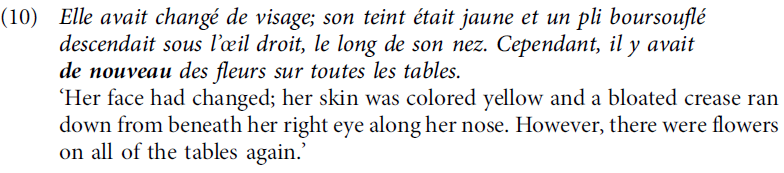

The idea that the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau might be at least partially governed by the repetitive-restitutive distinction seems to be in line with the only full-length analysis of this alternation on the basis of empirical data, namely Camus (Reference Camus1992). Camus (Reference Camus1992) analyzes the distribution of the two adverbials in a corpus of diverse text types and shows that their use is not always interchangeable. He claims that à nouveau always has a temporal, i.e. repetitive, meaning: “avec à nouveau, il ne s’établit de relation entre ei et ej que dans le temps” (Camus, Reference Camus1992: 20, where ei refers to the original and ej to the repeated event). In contrast, when de nouveau is used, the second event ej is construed as the reference point of the relation between ei and ej (Camus, Reference Camus1992: 21). Consider Camus’s (Reference Camus1992: 21–22) description of example (10), taken from Simone de Beauvoir’s Une mort très douce, in which the narrator describes how she visited her mother again in the hospital.

The first sentence in (10) indicates that whereas the narrator’s mother was doing well the last time she was visited by the narrator, this time her health condition has deteriorated. However, the use of cependant ‘however’ establishes a contrast between this perception and the content of the second sentence because the flowers on the tables indicate that the patient is healthy enough to be visited (Camus, Reference Camus1992: 22). De nouveau thus indicates that contrary to the narrator’s expectations, a state of affairs considered normal by the narrator, i.e. that there are flowers on the tables, was restored. According to Camus, it is this subjectivity that defines the use of de nouveau: “de nouveau implique en tout état de cause le point de vue d’un sujet sur la répétition” (Camus, Reference Camus1992: 21). In Camus’ view, using à nouveau in example (10) would lead to a ““détachement” de la narratrice vis-à-vis de l’état de choses rapporté, interprétation très peu probable dans le contexte large” (Camus, Reference Camus1992: 22).

Camus himself seems to imply that this subjective interpretation of de nouveau is ultimately derived from the restitutive value of de nouveau. Thus, he suggests that in example (11), taken from the translation of a science fiction novel about time travel, “ej (la jauge de puissance remonta de nouveau) annule le procès précédant (l’aiguille de la jauge de puissance tomba à zéro)” (Camus, Reference Camus1992: 22, italics in the original). The restitutive reading emphasizes the viewpoint of the subject, namely the time traveler, who has effected the change in the power gauge.

The crucial point here is that Camus’ analysis highlights an implicature resulting from the restitutive interpretation of de nouveau, namely the categorization of the original state of affairs as “normal” or “default”, which was already brought up in the discussion of examples (8) and (9) above. This implicature is closely associated with the perspective of the subject referent. Both in examples (10) and (11), the protagonists view the original states (there are flowers on the tables, the power gauge is up) as default states. Such an assessment can however only be made from a subjective perspective, which explains Camus’ interpretation of the opposition between à nouveau and de nouveau.

In his paper on the French prefix re-, Apothéloz (Reference Apothéloz2007) operates with a similar distinction, claiming that “quand re- produit un lexème à valeur annulative, celle-ci est toujours un « retour à l’état primaire », et pas seulement un « retour à un état antérieur »” (Apothéloz, Reference Apothéloz2007: 150). However, the return to “primary” or “default” state is necessarily a return to a previous state, too. Due to this entailment, I believe that it is problematic to differentiate between two readings restitutive1 (return to a previous state) and restitutive2 (return to a default state) when discussing ‘again’ adverbs and rather assume that restitutive2 is based on an implicature that can be derived from restitutive1.

In summary, Camus’ (Reference Camus1992) results can be interpreted as a first step towards formulating the hypothesis that the opposition between à nouveau and de nouveau is at least partially governed by the difference between repetitive and restitutive readings. In particular, the use of à nouveau is expected to be more likely in contexts denoting repetition, whereas the use of de nouveau should be more likely in contexts denoting restitution.

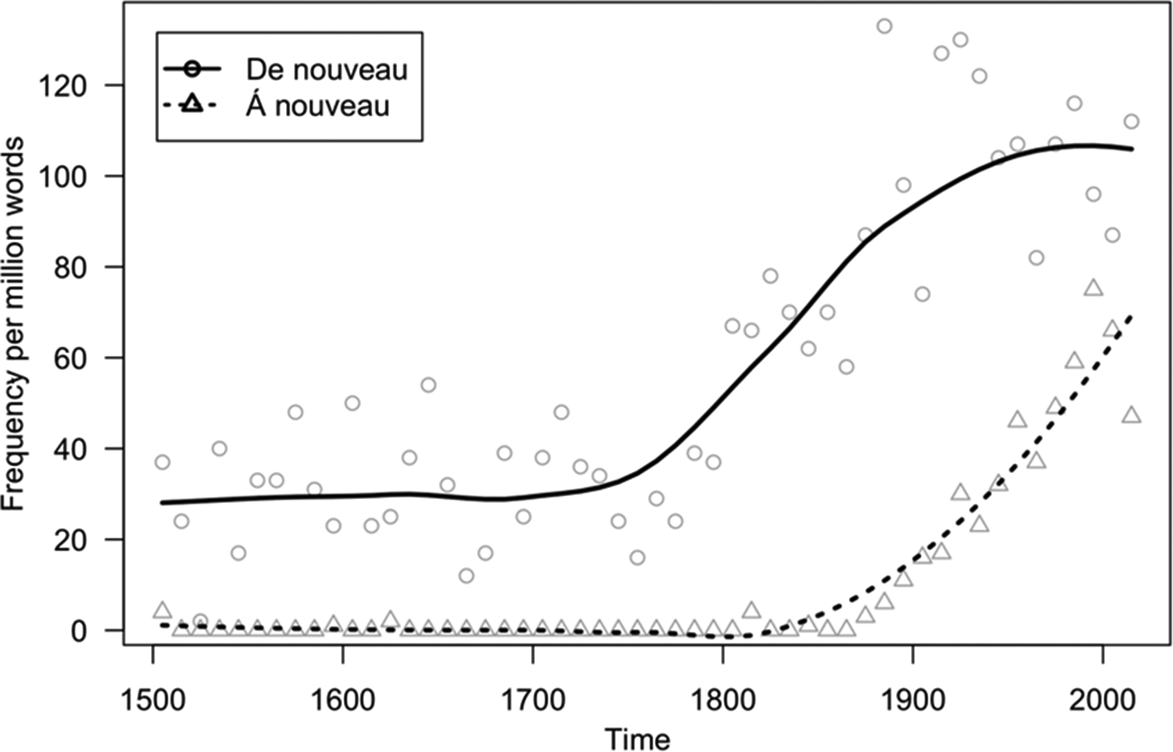

À nouveau and de nouveau also differ with respect to their historical development. While de nouveau is attested in Old and Middle French, à nouveau is an innovative variant that is only documented from the 19th century onwards (Grevisse and Goosse, 2008: 1263). Figure 1 visualizes the development of the usage frequencies of the two adverbials in the FRANTEXT corpus (ATILF - CNRS & Université de Lorraine, 2020), from 1500 to 2019 (5095 texts, about 245,5 million words). The data from FRANTEXT confirm that de nouveau is the older variant. While its usage frequency stagnates between 1500 and about 1750, it increases exponentially after 1750, reaching a plateau between 1950 and 2019. In contrast, the use of à nouveau is marginal between the beginning of the 19th century, when it starts experiencing a rapid rise in usage frequency that persists all the way to 2019. In doing so, it also rises gradually in terms of frequency relative to de nouveau. Before 1890, à nouveau is never used in more than 10 percent of the cases, whereas after 1990, it reaches about 43 percent.

Figure 1. Historical development of the usage frequencies of de nouveau (n = 23,239) and à nouveau (n = 6,341), normalized by one million words, in FRANTEXT. Shaded dots/triangles represent mean normalized usage frequencies in 10-year periods between 1500 and 2019, whereas the lines represent results from local polynomial regression models.

If de nouveau and à nouveau are in any sense synonymous, the results from Figure 1 would thus imply that à nouveau is starting to replace de nouveau. This might amount to a case of semasiological cyclicity (Hansen, Reference Hansen, Ghezzi and Molinelli2014, Reference Hansen2018), where two etymologically related forms “repeatedly develop […] similar context-level functions from a similar point of departure at the content level” (Hansen, Reference Hansen2018, p. 130). Crucially, Hansen’s work demonstrates that the renewal of the expression of meanings such as ‘[as of] now’ is not abrupt. For instance, despite the fact that it is the descendant of Latin iam, Old French ja did not just copy its function (Hansen, Reference Hansen, Ghezzi and Molinelli2014). Rather, ja started out with a rather reduced range of functions and came to gradually acquire the entire spectrum of functions that can be found in Latin iam independently from its predecessor. Taken together, this change can be described as a change from temporal to discourse-structuring, i.e. strongly pragmatic, readings.

In the present case, if à nouveau is indeed starting to replace de nouveau, we would expect à nouveau to gradually displace the use of de nouveau from certain usage contexts, starting out from rather specific contexts. This consideration leads to a second hypothesis that will be investigated in this paper, namely that in comparison to de nouveau, the usage contexts of à nouveau should be more restricted because à nouveau has only recently begun encroaching on the functional domain of de nouveau. Additionally, we might expect differences between à and de nouveau in terms of register (formal vs. informal situations) and medial orality (spoken vs. written language), in that the more innovative variant à nouveau might be more frequent in informal registers and spoken language (see Rosemeyer, Reference Rosemeyer2019).

2.2 Contextual indicators of repetitive and restitutive readings

Most of the examples involving à and de nouveau adduced until now are ambiguous between a repetitive and a restitutive reading. This ambivalence derives from a fundamental metonymy between these two readings, which can sometimes, but not always, be resolved when considering the extended context. At the beginning of Section 2.1, it was argued that repetitive ‘again’ asserts the repetition of an event, presupposing that the same event has happened before. In contrast, restitutive ‘again’ asserts the repetition of a state, which entails the existence of a previous event reversing the previous state. Consequently, both the repetitive and restitutive reading presuppose or entail the existence of a previous event, which is why in combination with predicates that lead to a resultant state, ‘again’ can receive either a repetitive or restitutive reading.

As a simple example, consider (12), taken from the newspaper L’Est Républicain. The author first claims that 50 percent of the Israeli forces have withdrawn from the Palestine territories, but have now reentered. The sentence involving à nouveau can be interpreted as both repetitive (the process leading to the presence of Israeli forces in Palestinian territory has happened again) or restitutive (Israeli forces are back in Palestinian territory). This is simply an issue of which component of the complex semantics of ‘enter’ (the event of entering or the resultant state of being inside’) is taken to be asserted.

Even if the extended co-text is considered, the metonymy between the repetitive and restitutive readings makes an evaluation of examples such as (12) in terms of this opposition difficult. Although a repetitive reading is favored, this does not make a restitutive reading impossible. The same holds for almost all examples that have been presented in this paper until now. Any annotation of sentences of à nouveau and de nouveau regarding the difference between repetitive and restitutive readings will be highly subjective and unreliable.Footnote 6 This calls for an indirect approach to the analysis of the opposition between the two adverbials, as opposed to case-by-case annotation.

Fortunately, the existing semantic literature on ‘again’ expressions has identified contextual predictors of the two readings, which can be used as indicators in a distributional analysis. First, stative predicates appear to be more prone to expressing restitutive readings than dynamic predicates, and especially activity predicates, because the possibility of a restitutive reading hinges on whether or not the assertion of a repetition has scope over a state. Thus, with activities such as run in (13a), use of ‘again’ adverbials leads to a repetitive interpretation. Note that the use of the present perfect substantially reinforces the repetitive reading (see below for details). In contrast, stative predicates modified by ‘again’ usually lead to a restitutive interpretation. For instance, Tovena and Donazzan claim that in their example (13b)

there is an eventuality which is an occurrence of a state of being angry experienced by Mary and that an analogous state for the same experiencer held at a previous time (Tovena and Donazzan, Reference Tovena and Donazzan2008: 100)

In other words, (13b) asserts the repetition of the previous state of Mary’s being angry.Footnote 7 One crucial aspect in the creation of this restitutive reading is Tovena and Donazzan’s mechanism of ‘lumping’, by which “information on its boundaries become available and the internal structure is neglected”, because without lumping, the state could not be interpreted as having a beginning nor an end, which is a prerequisite for the repetition of the state.

However, stativity is not a precondition for restitutive readings. A restitutive interpretation can also derive from non-stative predicates, especially when these predicates carry information about the resultant state of the repeated event e1. This applies to telic change of state verbs, whether intransitive or transitive, as demonstrated by (14). Such telic change of state verbs are composed of two semantic components, the event e1 (e.g. sitting down) and a state resulting from the event (being seated), caused by e1. As was already mentioned in the discussion of example (12), with such predicates, ‘again’ adverbials modify either the event, leading to a repetitive reading, or the resultant state, leading to a restitutive reading.Footnote 8 Consequently, a sentence such as (14a) can express either an eventive reading (‘when she (had) sat down’) or a stative-resultative reading (‘when she was sitting’). The difference between the non-stative and stative versions of these sentences is that “the process gives us an indication of how the asserted state has come about, i.e. of how it has been restituted” (Tovena and Donazzan, Reference Tovena and Donazzan2008, p. 101).

As also mentioned in Tovena and Donazzan (Reference Tovena and Donazzan2008: 101), the same applies to degree achievements such as (15), the sole difference being that the restituted state need not be exactly identical but rather in the same approximate range (‘it is dark again’); again, both a repetitive and restitutive interpretation are possible.

Finally, activity predicates are tricky in Romance languages such as French because, when inflected for imperfective aspect, they can be interpreted both as punctual events or habits (see example (1), repeated here as (16)). Whereas the punctual event interpretation leads to a repetitive meaning (‘Jeanne is running again’), the habitual interpretation actually represents a restitutive meaning (‘Jeanne has taken up the habit of running again’).

This ambiguity disappears to a great degree when the event is construed as bounded, as in (17), where the verb receives perfective aspect and no restitutive reading is possible. This would predict that in addition to predicate type, verbal aspect is another indicator of the opposition between repetitive and restitutive readings of de nouveau and à nouveau.Footnote 9

A further indicator of the repetitive/restitutive distinction is the use of temporal adverbs or adverbials that position the event in time. For instance, in (18), the use of the adverbial ce matin suggests a repetitive reading.

As was noted in von Stechow (Reference von Stechow1996) for German, the repetitive/restitutive opposition is also influenced by word order; in transitive subordinate clauses, placement of wieder ‘again’ after the object allows for both a repetitive and a restitutive reading, whereas placement of ‘again’ before the object only allows for the repetitive reading. Von Stechow claims that this difference in interpretation results from changes in the syntactic scope of wieder. The same situation might apply to French clauses, as shown in example (19). Due to the fact that in (19a) de nouveau modifies the entire clause, the clause can receive both a repetitive and a restitutive reading. In contrast, in the invented example (19b), a repetitive reading seems preferred because in this example, de nouveau only modifies the event as such, namely tendit la main.

In contrast to German, French also allows fronted ‘again’ adverbials. Intuitively, fronting of à or de nouveau seems to lead to a repetitive reading (see 20), which can be explained in terms of the notion of resumptive preposing (Cinque, Reference Cinque1990, pp. 88–89). Thus, “the fronted constituent […] contains an anaphoric element that creates a textual connection with a discourse antecedent” (Leonetti, Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017, p. 908). The anaphoricity of fronted ‘again’ adverbials resides in that, as in fronted comparatives (Leonetti, Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017: 909–910), the eventuality that is repeated must be retrieved from the previous co-text. It is due to this requirement that fronted à or de nouveau seem more likely to express a repetitive than a restitutive reading; in particular, this syntactic constellation instructs the hearer to go back into the previous context and retrieve a previous occurrence of the same event. In line with the hypothesis that à nouveau is more likely to express repetitive readings, we would consequently expect its use to be more likely in fronting contexts.

The same discourse-connecting effect applies in examples that do not denote the repetition of the eventuality referred to by the predicate. Consider, for instance, example (21), in which the sentence introduced with de nouveau serves to corroborate a hypothesis introduced earlier by the author (‘alcohol and cold together are doubly fatal’). The adverb links the present sentence to a previous assessment by the author. Like (20), the sentence expresses a repetitive reading; it however differs from (20) with respect to the nature of the repeated eventuality. In (21), the hearer needs to infer that the repetition is not meant to modify the meaning of the eventuality expressed by the predicate, but rather the speech act level. Just like other French temporal adverbs in the left clause periphery, such as maintenant (see Hansen, Reference Hansen2018, pp. 138–139), in such contexts à and de nouveau consequently have a pragmatic meaning and can maybe even be described as discourse markers.

Hansen (Reference Hansen2018) claims that maintenant and its older variants or and Latin nunc started out with a temporal meaning and came to acquire pragmatic discourse-connecting functions gradually over time. The same pragmaticalization process can be hypothesized to have taken place in examples such as (21), where de nouveau has extended its scope beyond the proposition of the sentence.Footnote 10 This diachronic perspective leads to a second, competing hypothesis regarding the influence of fronting on the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau; in particular, given that de nouveau is the older variant, it would be more likely to have developed such functions than à nouveau.

Summing up, if the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau is indeed governed by the type of iterative reading, we would expect the alternation to be sensitive to the contextual predictors described in this section. In particular, the use of de nouveau would be expected to be particularly likely with predicates that describe states or events leading to a resultant state, imperfective aspect, and less likely with temporal adverbs that describe the temporal position of the eventuality, and in transitive clauses in which the adverb precedes the object.

3. DATA

In this section, I describe the data extraction process (Section 3.1) and annotation procedures (Section 3.2).

3.1. Data extraction process

All tokens of à nouveau and de nouveau were extracted from the multimodal Corpus d’Etude pour le Français Contemporain (ORFEO, 2020, henceforth CEFC). The CEFC is made up from 15 corpora of spoken French (mostly conversations and sociolinguistic interviews, about 4 million words) and six corpora of written French (novels, press texts, scientific texts, and texts from the web and sms, about 6 million words). The resulting n = 883 tokens were restricted to texts and recordings after the 20th century, leading to the exclusion of all data from novels. Moreover, duplicates, verbless clauses (see 22) and one case with unclear syntax were deleted. These data homogenization procedures led to a final corpus of n = 505 tokens of à nouveau and de nouveau, which are distributed almost evenly (n à nouveau = 253, n de nouveau = 252).

3.2. Data annotation procedures

The data were coded manually in terms of the contextual predictors whose relevance was established in Section 2.

3.2.1 Predicate type

The variable PredicateType operationalizes the predicate type expressed by the clause. The operationalization followed the four criteria summarized in Table 1, namely whether the predicate implies a resultant state for the subject or object, or whether the subject is agentive. This lead to a classification that tried to refine Vendler’s (Reference Vendler and Vendler1967) original typology of predicate classes. Thus, while the levels “State” and “Activity” correspond to Vendler’s original definition, three additional classes were defined, which cannot be mapped univocally to Vendler’s concepts of “Achievement” and “Accomplishment”.

Table 1. Operationalization of the variable PredicateType

At this point, it is important to distinguish between resultant and target states, as defined in Parsons (Reference Parsons1990, pp. 234–235) and Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Conathan, Good, Karitskaya, Wulf and Yu2000). Resultant states can be defined as the state of the event having culminated. This means that every culminative event has a resultant state. In contrast, only some culminative events have a target state, defined as a state that is part of the complex eventuality and manifested as an attribute of one of the participants. In Parsons’ example I threw the ball onto the roof, the sentence yields both a resultant state (‘the state of my having thrown the ball onto the roof’) and a target state (‘the ball is on the roof’). Whereas the resultant state holds forever (the event cannot be undone), target states can be reversed. Consequently, when discussing restitutive meanings, it is important to classify verb meanings according to target states, not resultant states.

Change predicates are predicates that imply a punctual or gradual change of state experienced by the subject or the object, leading to a target state (in 23a, ‘Jeanne is home’, in 23b, ‘The door is open’). In contrast, manipulation predicates do not imply a change of state strictu sensu. For instance, in (23c), the action of refuting the argument does not lead to a target state ‘The argument is refuted’, which would be evident to further persons evaluating the argument. Like manipulation predicates, experience predicates do not lead to a target state for the object; for instance, the use of (23d) does not imply that the dog has experienced a change of state. In contrast to manipulation predicates, however, they involve a non-agentive subject and are atelic. Finally, punctual predicates are comparable to experience predicates in that they do not contain a stative subeventuality and are atelic; however, they vary with respect to the agentivity of the subject referent. Thus, in (23e) Jeanne might have bumped the table voluntarily or accidentally. Given the similarity between experience and punctual predicates and the fact that only two instances of punctual predicates were found (buter ‘bump’ and claquer ‘bang’), it was decided to collapse the two categories in the typology.

3.2.2 Tense, temporal adverbials and word order

The second variable, Tense, operationalizes the tense-aspect morphology of the verb in the clause, which is expressed in French using portmanteau morphemes on the main verb or the auxiliary. The following levels were distinguished: Present, Future, ImperfectivePast, PerfectivePast (both simple past and present perfect)Footnote 11 and Pluperfect.

Third, the variable PunctualTempAdv received the value “True” when a punctual temporal adverb(ial) such as cette année ‘this year’, hier ‘yesterday’, trois fois ‘three times’ etc. was used in the clause.

Finally, the variable WordOrder was used to classify the syntactic structure of the clause. Given that the previous research on this topic identified the position of the adverbial in the clause as crucial, the syntactic configurations were classified in terms of this parameter. Table 2 summarizes the operationalization of word order and gives examples.

Table 2. Operationalization of the variable WordOrder. Abbreviations: V = Verb, Adv = à/de nouveau, Obj = (lexical or clitic) Object

4. THE CLASSIFICATION OF REPETITIVE AND RESTITUTIVE READINGS: A CONFIRMATORY QUESTIONNAIRE STUDY

In a first analytical step, the relevance of the contextual predictors of the difference between repetitive and restitutive readings listed in Sections 2.2 and 3 was identified using a questionnaire study. Participants of the study were presented with sentences from the dataset collected from the CEFC and asked to evaluate whether they believed the sentence to express a repetitive or restitutive meaning (see Sections 4.2 and 4.3 below for details). This procedure also allowed me to gauge the degree to which sentences involving à nouveau or de nouveau are ambiguous between repetitive and restitutive readings. These measurements can in turn be used to operationalize the relevance of the contextual features under study for the interpretation process.

4.1. Participants

The questionnaire experiment was run via the web using the experimental environment OnExp developed in the Research Centre “Text Structures” at the University of Göttingen (https://onexp.textstrukturen.uni-goettingen.de/). 21 subjects were recruited from the online experimental platform profilic.co (https://www.prolific.co). All participants were native speakers of French who do not study languages and linguistics.

4.2 Experiment design

Subjects were asked to read n = 56 sentences from the dataset described in Section 3 in a self-paced reading paradigm. The entire experiment (instruction texts and stimuli) was conducted in French. After reading each sentence, they were asked to evaluate on a scale whether the sentence expressed that an event is repeated (value 1), that a state is restored (value 3), or an in-between meaning (value 2). Using two simple examples (Jeanne a couru de nouveau ‘Jeanne has run again’ and Jeanne est de nouveau à la maison ‘Jeanne is home again’, the participants were first instructed regarding the difference between repetitive and restitutive meanings. They were asked to rely on their intuition in discriminating these meanings for the sentences in the study without elaborating rules regarding the difference between the two meanings. No mention was made of the difference between à nouveau and de nouveau, and they were described as one and the same adverb (“l’adverbe “à/de nouveau””) in the introduction.

4.3 Materials

It was decided to take the stimuli sentences from the press subcorpus (n = 153) because the meaning of these sentences is easiest to understand without extended context. First, very short (less than 10 words) or long (more than 30 words) sentences were excluded from the materials list. Second, the data were reduced such that each verb occurred only once in the materials (for instance, this led to the exclusion of several sentences with the verb être ‘to be’). Third, the sentences were filtered manually for comprehensibility. The final dataset then contained a list of n = 56 sentences.

4.4 Results

In general, participants judged the sentences of the corpus to be more likely to express a repetitive meaning (n = 664) than a restitutive meaning (n = 427), with only n = 85 cases in which the participants were undecided. However, inspection of the dispersion of the answers across the n = 56 sentences revealed that the participants’ votes were far from unanimous. The mean agreement rate between the participants was 72.6 percent, ranging from a maximum of 95.2 percent for an example such as (24), to a minimum of 42.9 percent for an example such as (25). Example (24) received the following scores: n 1 = 20, n 2 = 0, n 3 = 1. Example (25) received the following scores: n 1 = 9, n 2 = 4, n 3 = 8.

Table 3 summarizes the judgments of the participants as a function of predicate type. As expected, the participants judged à nouveau and de nouveau to be more likely to express a resultative reading in sentences involving state predicates, and to some degree change predicates, than in sentences involving activity, manipulation, and experience predicates. Note, however, that these two predicate classes also represent the furthest ranges in terms of agreement rate; participants showed the highest agreement rates when presented with stative predicates and the lowest agreement rates when presented with change of state predicates. This observation is in line with the assumption, formulated in Section 2.2., that change of state predicates are especially ambiguous in terms of the distinction between repetitive and restitutive readings.

Table 3. Answers by the participants in the questionnaire study, by predicate type

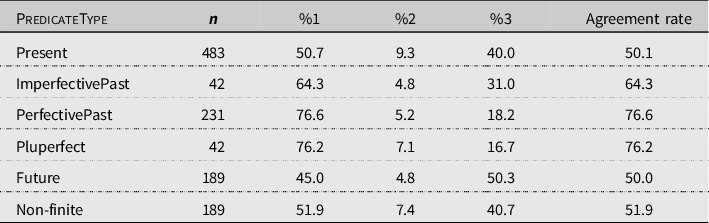

Table 4 summarizes the participants’ judgments as a function of tense. Clauses with verbs inflected for future, present, imperfective past, or non-finite verbs, were classified as restitutive more frequently than clauses with verbs inflected for perfective past or pluperfect. In this case, too, it is instructive to look at the agreement rates; participants showed the highest agreement rates for sentences involving perfective past or pluperfect, suggesting that these tenses are particularly strong cues as to whether a sentence involving à nouveau or de nouveau should be interpreted as repetitive or restitutive.

Table 4. Answers by the participants in the questionnaire study by tense

Table 5 summarizes the results for the variable PunctualTempAdv, indicating whether or not a punctual temporal adverb(ial) is used in the clause. The results show that the presence of a punctual temporal adverb(ial) leads to much less frequent classifications of the clauses as restitutive. Note the markedly higher agreement rate for sentences involving a punctual temporal adverb(ial), which likewise indicates the relevance of this parameter for the interpretation process.

Table 5. Answers by the participants in the questionnaire study by presence of punctual temporal adverb(ial)s

Finally, Table 6 summarizes the distribution of the judgments by the participants as a function of word order. While not all word orders described in Section 3 were represented in the sample, the results suggest in particular that clauses with sentence-initial à/de nouveau are more likely to be classified as repetitive, whereas intransitive sentences are more likely to be classified as restitutive. In the group of transitive sentences, no significant difference seems to exist between the word orders VAdvObj and VObjAdv. The highest agreement rates are found for the AdvV word order.

Table 6. Answers by the participants in the questionnaire study by word order

By and large, the results from the questionnaire study confirm the relevance of the contextual predictors of predicate type, tense and modification with temporal adverb(ial)s for the interpretation of a sentence as repetitive or restitutive.Footnote 12 First, a repetitive reading appears much more likely with activity and manipulation predicates than with state predicates, and somewhat more likely with change and experience predicates. Second, repetitive readings are favored when the verb receives perfective past or pluperfect morphology. Third, a repetitive reading is much more likely in sentences involving a punctual temporal adverbial such as ce matin ‘this morning’, than in other sentences.

Regarding the variable WordOrder, the questionnaire study did not find a strong difference between VAdvObj and VObjAdv orders, which were hypothesized to influence the reading of à and de nouveau in Section 2.2. As predicted, participants did, however, associate fronted à and de nouveau with repetitive readings.

5. THE ALTERNATION BETWEEN À NOUVEAU AND DE NOUVEAU

Having established the relevance of most of the predictors of the repetitive/restitutive opposition in a subsection of the corpus, we are now in a position to evaluate the hypothesis that the difference between à nouveau and de nouveau is governed by the repetitive/restitutive opposition.

On the basis of the results of the questionnaire study, a numerical variable Repetitive was created that measured the likelihood for each sentence or utterance in the data to express a repetitive over a restitutive reading in a bottom-up approach. Table 7 summarizes the operationalization process for this variable. Starting out with an initial value of 0 (representing the highest likelihood for a sentence or utterance to express a restitutive reading), the algorithm incrementally assigned points to the Repetitive variable as a function of the contextual properties represented by PredicateType, Tense, and PunctualTempAdv. Due to the mixed results regarding the variable WordOrder in the questionnaire study (cf. also footnote 12 above), this variable was not included as a parameter for the operationalization of Repetitive. Two conditions received particular weight, because they were judged as particularly important in the questionnaire study: activity and manipulation predicates, and the presence of punctual temporal adverb(ial)s. Note that the maximum attained score for Repetitive was.

Table 7. Operationalization process for the predictor variable Repetitive (initial value of repetitive = 0)

In (26), I give three examples of the result of this classification process from the corpus. With 5 points, (26a) is predicted to express a repetitive reading, whereas with 0 points, (26c) is predicted to express a restitutive meaning. With 3 points, (26b) is predicted to be ambivalent (note that the predicate remplacer is a change of state predicate, which were shown in Section 4 to be more susceptible to lower agreement rates).

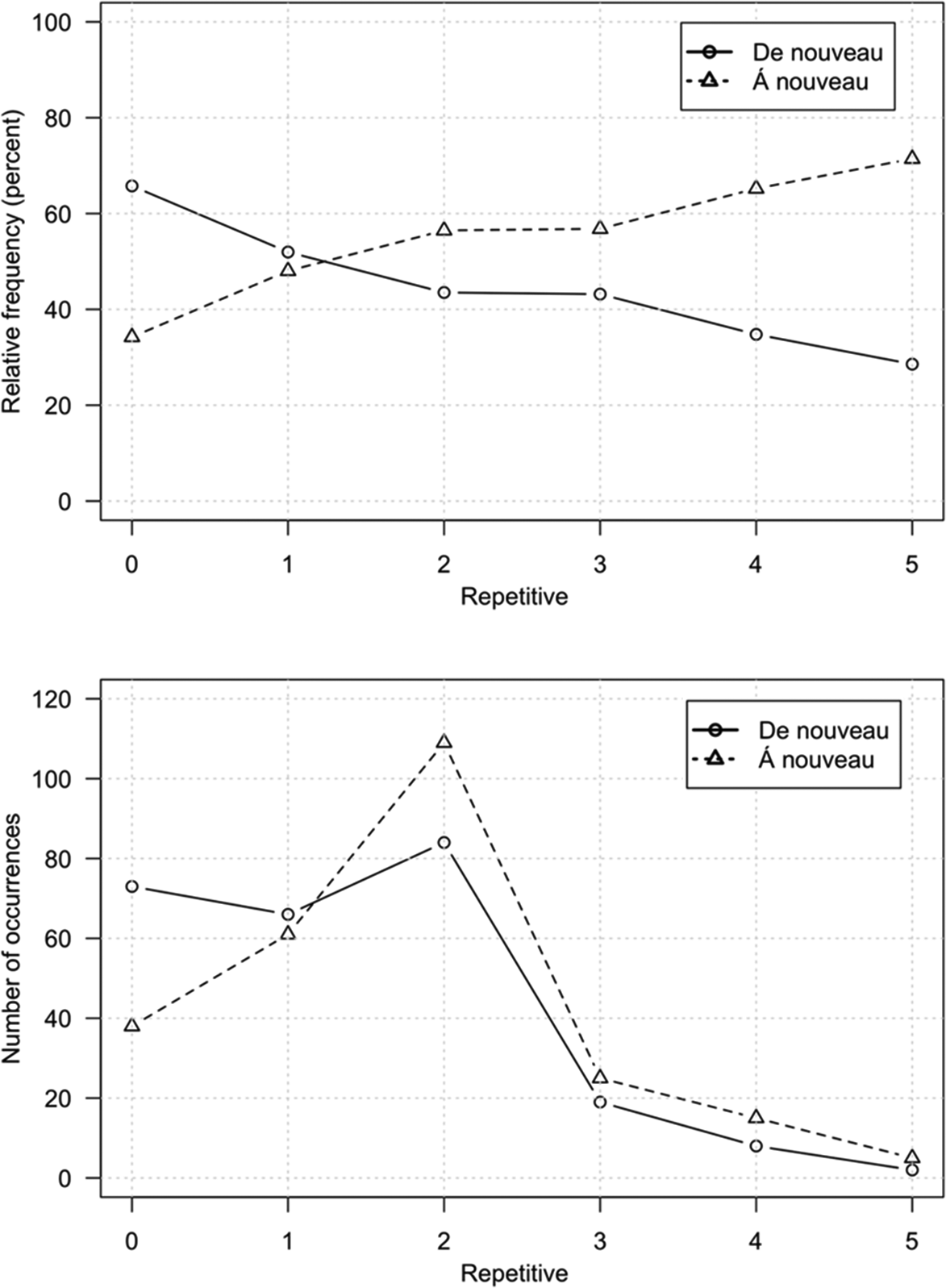

Figure 2 visualizes the distribution of à nouveau and de nouveau in terms of the Repetitive variable as relative frequencies, i.e. percentages (upper plot), and absolute frequencies, i.e. numbers of occurrences (lower plot). Inspection of the relative frequencies suggests that in comparison to à nouveau, de nouveau is generally more likely to express a restitutive meaning than a repetitive meaning. In particular, de nouveau displays a specialization for a restitutive reading (relatively high incidence of de nouveau in contexts in which Repetitive takes a score between 0 and 2, relatively low incidence in contexts in which Repetitive takes a score between 3 and 5), whereas à nouveau is specialized in the expression of repetitive meanings, with the inverse distribution. Crucially, the only context in which de nouveau has a markedly higher relative frequency are sentences like (26c) that score lowest on the Repetitive variable (i.e. 0). In general, the relative usage frequency of à nouveau is higher even in sentences like (26b), which were classified as ambiguous (Repetitive score of 2 or 3).Footnote 13

Figure 2. Distribution of à nouveau and de nouveau by Repetitive.

It is also instructive to inspect the absolute usage frequencies of à nouveau and de nouveau with respect to their scores on the Repetitive variable (lower plot in Figure 2). In particular, the usage frequency of à nouveau is much higher in sentences that achieved a Repetitive score of 2 (roughly corresponding to the middle of the distribution) than with other Repetitive scores, whereas the usage frequency of de nouveau remains relatively stable between sentences classified as 1-3 in terms of the Repetitive score. With n = 431 in a total of n = 505 occurrences, these sentences make up the bulk of the data, which indicates a generality of the use of de nouveau compared to a more specialized distribution of à nouveau.

A second indicator of the greater specialization of à nouveau is its lower incidence in sentences in which the adverbial precedes the verb. Recall that in Section 2.2., it was argued that in such contexts, ‘again’ adverbials can have obtained a pragmatic meaning due to a historical pragmaticalization process, leading to the expectation that the use of de nouveau be more frequent in such contexts. Table 8 represents the distribution of the two adverbials by word order, demonstrating that generally, the use of à nouveau is more frequent in sentences in which the adverb is positioned after the verb (V+Adv), whereas the use of de nouveau is more frequent in sentences in which the adverb is positioned before the verb (Adv+V). VObjAdv sentences, in which the use of de nouveau is likewise frequent, are an exception to this rule.

Table 8. Distribution of à nouveau and de nouveau by WordOrder

In order to refine the analysis and assess the statistical significance of the findings, a mixed-effects logistic regression model (see, e.g., Levshina, Reference Levshina2015, pp. 253–254) was calculated that predicted the likelihood of the use of à nouveau versus de nouveau in the entire dataset (n = 505) from the predictor variables summarized in Table 9. By virtue of not only including fixed effects but also the random intercept Predicate, the regression controlled for inter-predicate variation, i.e. variation in the use of à nouveau and de nouveau due to the use of specific predicates. It thus captured the fact that the predicates found in the dataset represent a random sample of a much higher number of predicates that could be found in a greater dataset. The regression model was calculated in R (R Development Core Team, 2019), using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker, Walker, Bojesen Christensen and Singmann2016). In a first step of the model building, I also tested for an interaction between Repetitive and Genre, which however did not lead to a significant increase in the model quality and was therefore discarded.

Table 9. Predictor variables in the mixed-effects logistic regression model predicting the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau

With a c index of 0.82, the model reached a reasonable discrimination (Hosmer and Lemeshow, Reference Hosmer and Lemeshow2000, p. 162), especially considering the reduced number of variables that were tested. The model predicted correctly 71 percent of the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau.

Table 10 summarizes the results from the regression model. The variables Repetitive and Genre are found to significantly influence the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau even when controlling for inter-predicate variation.

Table 10. Results from the mixed-effects logistic regression model predicting the use of à nouveau versus de nouveau. Abbreviations: LO = log odds, OR = odds ratio, StE = standard error, Z = z value, P = p value. Significance levels: p < .05*, p < .01**, p < .001***

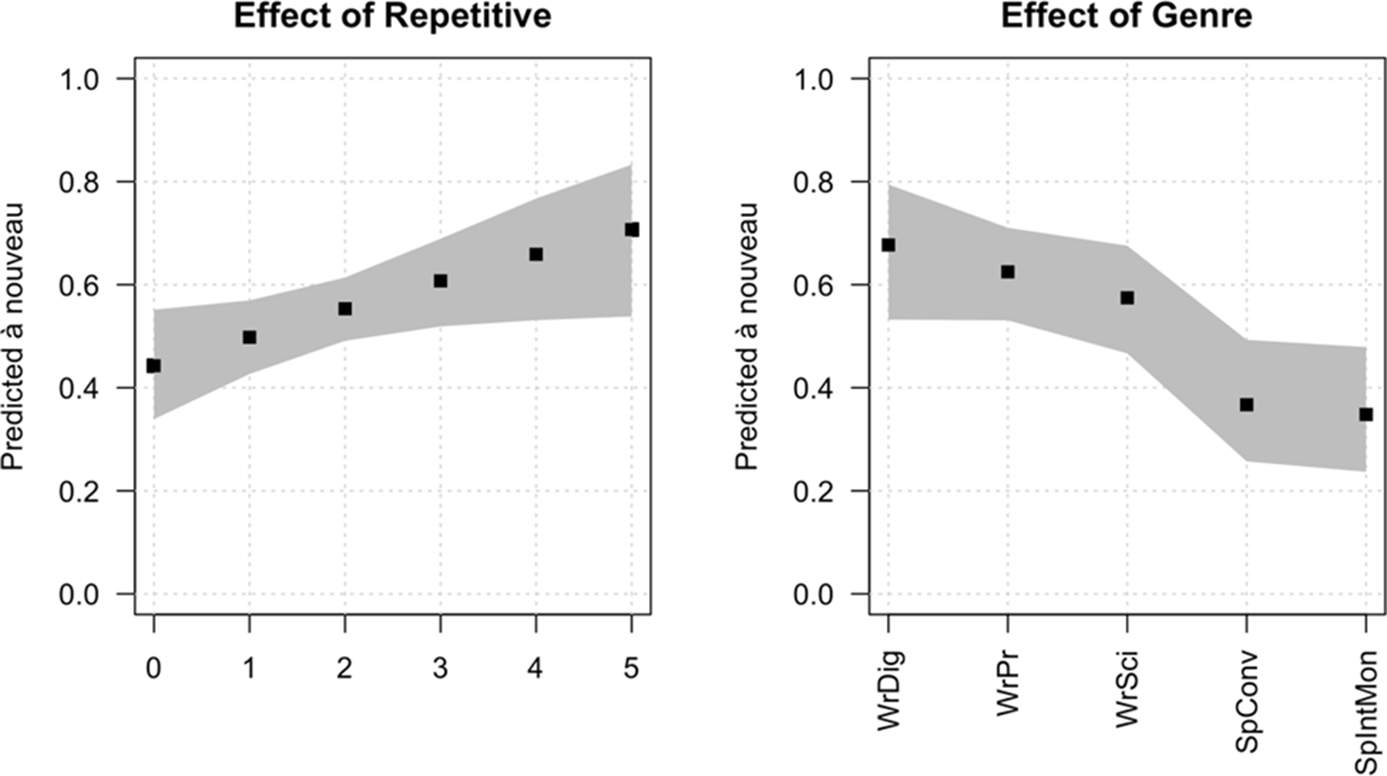

The effects of Repetitive and Genre on the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau are plotted in Figure 3. The likelihood of use of à nouveau increases with an increasing value of Repetitive, corroborating the descriptive analysis in Figure 2. Regarding the effect of Genre, the plot demonstrates a significant difference between written and spoken texts, in that, surprisingly, the use of à nouveau is relatively more likely in written than spoken texts. The genre effects within written and spoken texts are negligible.

Figure 3. Predicted use of à nouveau versus de nouveau by Repetitive and Genre. Shaded areas represent confidence intervals. Abbreviations for Genre: WrDig = WrittenDigital, WrPr = WrittenPress, WrSci =WrittenScientific, SpConv = SpokenConversation, SpIntMon = SpokenInterview/Monologue.

The results from the regression analysis clearly support the assumption that à nouveau is more likely than de nouveau to express a repetitive reading. Even when controlling for genre and inter-predicate variation, the relative likelihood of use of à nouveau only reaches about 38 percent in contexts that are judged very likely to express a restitutive meaning (Repetitive = 0), whereas with about 75 percent, its use is predicted to be very likely in contexts strongly associated to a repetitive meaning (Repetitive = 5). The analysis did not find any evidence that this effect is moderated by genre and medial orality, as inclusion of the interaction between Repetitive and Genre did not significantly increase the model quality. However, the analysis did find a significant main effect of Genre in that the use of à nouveau is predicted to be less likely in spoken than in written texts; speakers thus appear to prefer using de nouveau in spoken language.

6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

This paper represents the first study that tries to account for the variation between à nouveau and de nouveau on the basis of a quantitative analysis of written and spoken corpus data. Whereas most existing descriptions of the two adverbials either assume that à nouveau and de nouveau are synonymous or differ with respect to meaning nuances within the domain of repetitive iteration (‘unmarked’ repetition vs. ‘repetition in a different manner’), the present paper has pursued the hypothesis, inspired by typological studies, that the two adverbials differ in terms of the expression of repetitive and restitutive meanings. In a first analytical step, the contextual predictors of the difference between repetitive and restitutive meanings were identified by testing speaker intuitions on actual corpus data in an online questionnaire study. In a second step, the relevance of these contextual predictors for the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau in the corpus data was tested.

The results of the analysis suggest that à nouveau and de nouveau indeed differ with respect to the likelihood for either adverbial to appear in contexts representing repetitive or restitutive meanings. À nouveau is more likely to express repetitive meanings, whereas de nouveau is more likely to express restitutive meanings, as evinced by preferences in terms of predicate type, tense and aspect, and modification by temporal adverb(ial)s.

In terms of the global distribution of ‘again’ expressions in French, it would thus seem that à nouveau and de nouveau differ with respect to which other ‘again’ expressions they compete with. Thus, à nouveau is predicted to strongly compete with encore ‘again, still’, which does not express restitutive meanings. In contrast, de nouveau is expected to compete with the re-prefix, which is also very frequently used for the expression of restitutive meanings. A crucial difference between de nouveau and the re-prefix concerns the potential for lexicalization of the connection between the predicate and the ‘again’ expression, which is much higher for the re-prefix (consider predicates such as rénover ‘to renovate’ that have become semantically intransparent).

The analysis also found evidence for the second hypothesis, namely, that the use of à nouveau is more restricted than the use of de nouveau due to the fact that à nouveau represents the younger variant. In particular, whereas a strong association between the use of à nouveau and the expression of repetitive meanings was found, the distribution of de nouveau with respect to the repetitive-restitutive dimension was found to be more balanced. Likewise, it was found that de nouveau is more likely to express discourse-connective readings, in which ‘again’ does not have scope over the eventuality expressed by the proposition but rather asserts the repetition of a previous speech act by the speaker or writer. I hypothesized that these readings can be attributed to a historical pragmaticalization process; in line with the notion of semasiological cyclicity, the difference between de nouveau and à nouveau regarding the likelihood to express such readings is explained by the fact that as the younger variant, à nouveau has had less time to develop these readings.

Finally, the analysis documented diamesic preferences in the use of à nouveau and de nouveau. In my data, the use of à nouveau is relatively more likely in written texts, whereas the use of de nouveau is preferred in spoken language. This result is contrary to expectations (it was hypothesized that as the more recent variant, the use of à nouveau should be more likely in informal situations and spoken language) and could not be attributed to the repetitive/restitutive meaning difference. Likewise, no interaction between the dimensions of conceptual orality and grammatical meaning were found. One of the anonymous reviewers of this paper found a roughly equal frequency of the two adverbials in three other corpora of spoken French (the CFPP2000, CLAPI and PFC), with n = 88 occurrences of à nouveau and n = 80 occurrences of de nouveau. This finding indeed contrasts with my results; in the spoken section of the CEFC, I found n = 123 occurrences of de nouveau and only n = 57 occurrences of à nouveau.Footnote 14 Further studies of the alternation in terms of conceptual orality, discourse traditions and, possibly, dialectal differences are necessary to explain this contrast.Footnote 15

It is important to note that the regression analysis predicting the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau reached only a moderate, however acceptable, fit to the data. In other words, there is still much variation unaccounted for by the present analysis, which is why I believe further studies should attempt to refine the analysis proposed in this paper. In principle, this can be achieved in two ways. First, it may be that the operationalization of the contextual predictors of the repetitive/restitutive opposition proposed in this study is still lacking. This concerns especially the fact that the study is essentially based on the analysis of sentences or utterances, whereas due to their status as presuppositions, repetitive and restitutive meanings of à nouveau and de nouveau should be properly defined as discourse phenomena. In other words, the contextual predictors of the repetitive/restitutive opposition identified in this study are just that, contextual predictors, whereas the aspectual meaning of a sentence will frequently be unambiguous in a specific discourse context in which, for instance, the event that is being repeated has been mentioned before. Second, it might of course be the case that the alternation between à nouveau and de nouveau is governed by further parameters that have not received attention in this study, in particular, sociolinguistic variables such as dialectal variation and inter-speaker variation. In the light of the strong effect of the repetitive/restitutive dimension documented in this paper, it however seems unlikely that such an analysis will contradict the main finding of this study: whereas à nouveau typically expresses repetitive iteration, de nouveau typically expresses restitutive iteration.

Acknowledgements

This article was discussed at length with many colleagues from the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg as part of my habilitation thesis. I am very grateful for this inspiring discussion. I would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers at the Journal of French Language Studies, who went to great lengths to improve the quality of the article. Their detailed and thorough comments have impacted the analysis substantially and beneficially.