Introduction

Since April 2022, an increasing number of countries reported confirmed cases of the mpox virus (also known as the monkeypox virus) with transmission chains not linked to endemic countries [Reference Mitjà, Ogoina, Titanji, Galvan, Muyembe, Marks and Orkin1, Reference León-Figueroa, Barboza, Garcia-Vasquez, Bonilla-Aldana, Diaz-Torres, Saldaña-Cumpa, Diaz-Murillo, Cruz and Rodriguez-Morales2]. On 23 July 2022, the WHO Director-General determined that the mpox outbreak constituted a public health emergency of international importance [3]. As of August 16, 16162 mpox cases had been reported in Europe [4].

In Europe, Spain was the most affected country, followed by Germany and France. The epidemic curve followed similar trends in these countries, peaking in the first week of July and starting to decrease during the second half of the month [5]. The basic reproduction number R0 of the disease has been computed for some European countries [Reference Guzzetta, Mammone, Ferraro, Caraglia, Rapiti, Marziano, Poletti, Cereda, Vairo, Mattei, Maraglino, Rezza and Merler6–Reference Endo, Murayama, Abbott, Ratnayake, Pearson, Edmunds, Fearon and Funk8], and estimates on the effective reproduction number and instantaneous growth rate are available as well for some countries [Reference Ward, Christie, Paton, Cumming and Overton9–Reference Schrarstzhaupt, Fontes-Dutra and Diaz-Quijano11].

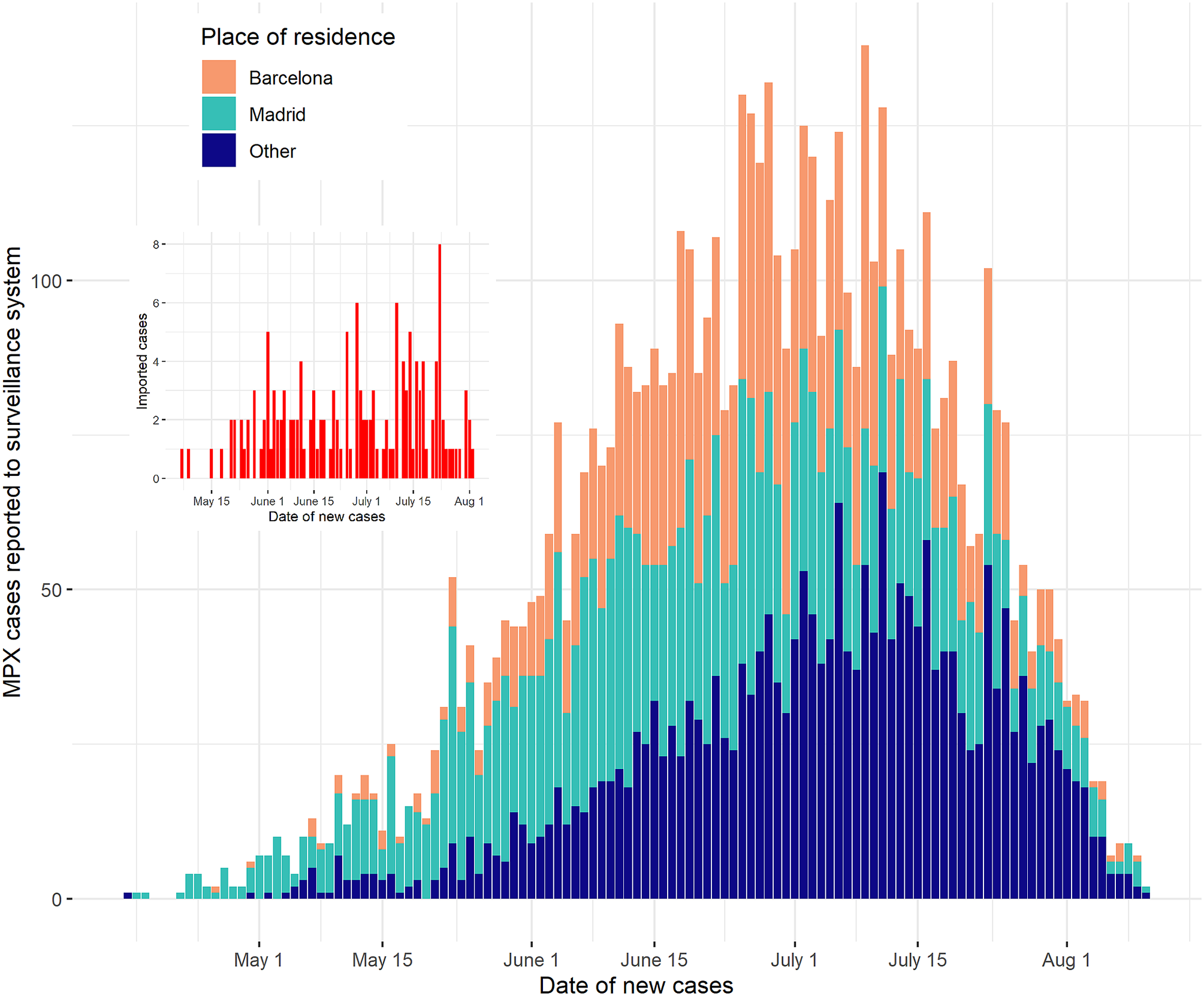

The first case in Spain was identified retrospectively on 25 April 2022 [12, Reference Suárez Rodríguez, Guzmán Herrador, Díaz Franco, Sánchez-Seco Fariñas, del Amo Valero, Aginagalde Llorente, de Agreda, Malonda, Castrillejo, Chirlaque López, Chong Chong, Balbuena, García, García-Cenoz, Hernández, Montalbán, Carril, Cortijo, Bueno, Sánchez, Linares Dópido, Lorusso, Martins, Martínez Ochoa, Mateo, Peña, Antón, Otero Barrós, Martinez, Jiménez, Martín, Rivas Pérez, García, Response Group, Soria and Sierra Moros13]. Since then, 6284 confirmed cases had been notified to the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network (RENAVE [14, 15]) as of 19 August 2022. This made Spain the non-endemic country with the most confirmed cases in the European region at the time, reporting the second highest number of cases in the world [16]. The spatial distribution of these was not homogeneous: Madrid and Barcelona provinces hosted 35% and 28% of the total cases, respectively (Figure 1). To date, the disease is predominantly prevalent among men, with less than 2% of the cases being notified among women. Two patients under 3 years old have also been reported, as well as two deceased cases.

Figure 1. Epidemic curve of MPX in Spain, Madrid, and Barcelona, 25 April–19 August 2022. The date of new cases was obtained as the date of the onset of symptoms, offset by the incubation period.

Even though the incidence of the disease decreased substantially in Europe after the autumn of 2022 winter of 2022, further epidemiological insights are still to be drawn from the outbreak [Reference Mitjà, Ogoina, Titanji, Galvan, Muyembe, Marks and Orkin1, Reference León-Figueroa, Barboza, Garcia-Vasquez, Bonilla-Aldana, Diaz-Torres, Saldaña-Cumpa, Diaz-Murillo, Cruz and Rodriguez-Morales2]. While several studies in the country have addressed the clinical characteristics of the disease [Reference Tarín-Vicente, Alemany, Agud-Dios, Ubals, Suñer, Antón, Arando, Arroyo-Andrés, Calderón-Lozano, Casañ, Cabrera, Coll, Descalzo, Folgueira, García-Pérez, Gil-Cruz, González-Rodríguez, Gutiérrez-Collar, Hernández-Rodríguez, López-Roa, de los Ángeles Meléndez, Montero-Menárguez, Muñoz-Gallego, Palencia-Pérez, Paredes, Pérez-Rivilla, Piñana, Prat, Ramirez, Rivero, Rubio-Muñiz, Vall, Acosta-Velásquez, Wang, Galván-Casas, Marks, Ortiz-Romero and Mitjà17–Reference Orviz, Negredo, Ayerdi, Vázquez, Muñoz-Gomez, Monzón, Clavo, Zaballos, Vera, Sánchez, Cabello, Jiménez, Pérez-García, Varona, del Romero, Cuesta, Delgado-Iribarren, Torres, Sagastagoitia, Palacios, Estrada, Sánchez-Seco, Ballesteros, Baza, Carrió, Chocron, Fedele, García-Amil, Herrero, Homen, Mariano, Martínez-Burgoa, Molero, Navarro, Núñez, Perez-Somarriba, Puerta, Rodríguez-Añover, Pastrana, Jiménez, de la Vega, Vergas and Zarza19], assessments of the factors relevant to the containment of the disease at the population level are still in need. These are expected to provide valuable guidance in the design of effective public health policies and improved preparedness for future outbreaks of the disease or other diseases sharing epidemiological features with it.

Here, we compute estimates of the effective reproduction number (Rt) during the mpox outbreak in Spain, to evaluate the evolution of its transmission and to investigate its possible differences across different subgroups of the population. In particular, we consider transmission across geographical regions of the country and transmission across men who have sex with men (MSM) and heterosexual individuals, as both the geographical setting [Reference Orviz, Negredo, Ayerdi, Vázquez, Muñoz-Gomez, Monzón, Clavo, Zaballos, Vera, Sánchez, Cabello, Jiménez, Pérez-García, Varona, del Romero, Cuesta, Delgado-Iribarren, Torres, Sagastagoitia, Palacios, Estrada, Sánchez-Seco, Ballesteros, Baza, Carrió, Chocron, Fedele, García-Amil, Herrero, Homen, Mariano, Martínez-Burgoa, Molero, Navarro, Núñez, Perez-Somarriba, Puerta, Rodríguez-Añover, Pastrana, Jiménez, de la Vega, Vergas and Zarza19–Reference Betancort-Plata, Lopez-Delgado, Jaén-Sanchez, Tosco-Nuñez, Suarez-Hormiga, Lavilla-Salgado, Pisos-Álamo, Hernández-Betancor, Hernández-Cabrera, Carranza-Rodríguez, Briega-Molina and Pérez-Arellano21] and sexual activity have been identified as relevant factors in the spread of the disease [Reference Mitjà, Ogoina, Titanji, Galvan, Muyembe, Marks and Orkin1, Reference Català, Clavo-Escribano, Riera-Monroig, Martín-Ezquerra, Fernandez-Gonzalez, Revelles-Peñas, Simon-Gozalbo, Rodríguez-Cuadrado, Castells, de la Torre Gomar, Comunión-Artieda, de Fuertes de Vega, Blanco, Puig, García-Miñarro, Fiz Benito, Muñoz-Santos, Repiso-Jiménez, López Llunell, Ceballos-Rodríguez, García Rodríguez, Castaño Fernández, Sánchez-Gutiérrez, Calvo-López, Berna-Rico, de Nicolás-Ruanes, Corella Vicente, Tarín Vicente, de la Fernández de la Fuente, Riera-Martí, Descalzo-Gallego, Grau-Perez, García-Doval and Fuertes18, Reference Thornhill, Palich, Ghosn, Walmsley, Moschese, Cortes, Galliez, Garlin, Nozza, Mitja, Radix, Blanco, Crabtree-Ramirez, Thompson, Wiese, Schulbin, Levcovich, Falcone, Lucchini, Sendagorta, Treutiger, Byrne, Coyne, Meyerowitz, Grahn, Hansen, Pourcher, DellaPiazza, Lee, Stoeckle, Hazra, Apea, Rubenstein, Jones, Wilkin, Ganesan, Henao-Martínez, Chow, Titanji, Zucker, Ogoina and Orkin22].

Material and methods

We used confirmed cases notified to the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network (RENAVE) from 25 April to 19 August 2022. These were used in the method of Cori et al. [Reference Cori, Ferguson, Fraser and Cauchemez23–25] to estimate the Rt of the disease. Several factors were taken into account for this:

-

– The date for new cases was chosen to be the date of the onset of symptoms, offset by the incubation period (see the next item), as usual when computing Rt estimates [Reference O’Driscoll, Harry, Donnelly, Cori and Dorigatti26]. No asymptomatic transmission was assumed in the model. While some instances of transmission from individuals presenting no mpox-related symptoms have been observed [Reference de Baetselier, van Dijck, Kenyon, Coppens, Michiels, de Block, Smet, Coppens, Vanroye, Bugert, Girl, Zange, Liesenborghs, Brosius, van Griensven, Selhorst, Florence, van den Bossche, Ariën, Rezende, Vercauteren, van Esbroeck, Ramadan, Platteau, van Looveren, Baeyens, van Hoyweghen, Mangelschots, Heyndrickx, Hauner, Willems, Bottieau, Soentjens, Berens, van Henten, Bracke, Vanbaelen, Vandenhove, Verschueren, Ariën, Laga, Vanhamel and Vuylsteke27, Reference Ferré, Bachelard, Zaidi, Armand-Lefevre, Descamps, Charpentier and Ghosn28], their occurrence has been rare. We thus assume that these do not represent a significant source of infection and that their possible effect on the model output can be disregarded.

-

– The output dates of the model were offset by an incubation time of 9 days [25], in agreement with several findings in the literature [3, Reference Guzzetta, Mammone, Ferraro, Caraglia, Rapiti, Marziano, Poletti, Cereda, Vairo, Mattei, Maraglino, Rezza and Merler6, Reference Miura, van Ewijk, Backer, Xiridou, Franz, op de Coul, Brandwagt, van Cleef, van Rijckevorsel, Swaan, van den Hof and Wallinga29].

-

– The serial interval was assumed to be gamma-distributed with a 9.8-day average and a 3.875-day standard deviation, as estimated by WHO [3].

-

– We performed a descriptive sensitivity analysis for the choice of the smoothing window. We computed Rt estimates for 3- to 13-day-long smoothing windows (leaving the rest of the parameters fixed) and chose the value that seemed to provide a more balanced compromise between detail and variability in the estimate upon visual examination of the resulting curves.

-

– In total, 151 out of 6284 cases (2.4%) were notified as imported (a case is defined as imported in RENAVE if the probable place of infection was outside of the country). Although the information on this variable is not always complete, these were included as imported cases in the method of Cori et al. In addition to this, the first recorded case in each of the regions under study was also labelled as imported when performing region-specific Rt estimates. This is a requirement of the method of Cori et al. [Reference Cori, Ferguson, Fraser and Cauchemez23, Reference Thompson, Stockwin, van Gaalen, Polonsky, Kamvar, Demarsh, Dahlqwist, Li, Miguel, Jombart, Lessler, Cauchemez and Cori24], which assumes that the first infection in each region was not caused by local transmission.

A summary of the chosen parametrisation is shown in Table 1. We also estimated the Rt in specific groups from the entire set of cases, in search for epidemiologically relevant differences. For this, we computed the Rt considering as input data only those cases with particular features. The resulting curves describe how transmission evolves within distinct subgroups of the population. We then compared the resulting curves by visual inspection and looked for apparent differences between them. This was done for three different groupings of the population:

-

– Madrid and Barcelona provinces. These two provinces hosted most of the mpox cases in the country, especially during the initial burst phase of the outbreak. National transmission trends were thus expected to be dominated by cases residing in these provinces.

-

– Mobility-based communities. We divided the total population of the country into seven ‘communities’, comprising several provinces. These communities were identified using clustering algorithms on a large data set of mobility data based on cellular network data, published by the Spanish Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda [30]. These communities should be understood as mobility clusters, in the sense that intracommunity movement is significantly more likely than intercommunity displacement. The role played by these communities in disease spread has been verified for other infectious diseases [Reference Del-Águila-Mejía, García-García, Rojas-Benedicto, Rosillo, Guerrero-Vadillo, Peñuelas, Ramis, Gómez-Barroso and Donado-Campos31]. See Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S2 for explicit descriptions of the communities.

-

– MSM and heterosexual population. Transmission across individuals who identified themselves as heterosexual and MSM was also computed. MSM who declared having a female sexual partner during the 21 days previous to the onset of symptoms were removed from this grouping.

Table 1. Model parametrisation

Summary of the parameter values used in the method of Cori et al. [Reference Cori, Ferguson, Fraser and Cauchemez23] to estimate the effective reproduction number.

Results

After a steady increase in the number of weekly declared cases of the disease, the outbreak seemed to stabilise and slightly decrease in July and August, by looking at the number of new daily cases (Figure 1). The sensitivity analysis showed qualitatively similar results, with longer smoothing windows leading to estimates with smaller short-term variations, as expected (Supplementary Figure S1). We chose a 5-day-long smoothing window after inspecting the resulting curves. The results reported in the article were consistent upon variations in this parameter and showed little or no change for different choices of it. In particular, we found a generally decreasing trend in Rt, with a decrease below 1 on July 12 when using a 5-day smoothing window (Figure 2), and at most a 1-day variation on this date for 3- to 13-day smoothing windows (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2. MPX effective reproduction number (Rt) in Spain, 25 April 2022–10 August 2022. Shaded area represents 95% confidence interval.

The evolution of the Rt for cases located in Madrid and Barcelona presented apparent differences during the first month of the outbreak: transmission in Madrid seemed to decrease from an initial maximum peak, while transmission in Barcelona seemed to start at a low point, then increased quickly, and decreased again afterwards, although higher uncertainty was found for the estimate in Barcelona (Figure 3). After May 25, both curves seemed to stabilise in a slowly decreasing trend.

Figure 3. MPX effective reproduction number (Rt) in Madrid and Barcelona, 25 April 2022–10 August 2022. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Several transmission patterns were found for the transmission in mobility-based communities (Figure 4). Three communities (Central East, Central West, and Canary Islands) showed a general decrease with some oscillations after an initial peak, similarly to Madrid. The transmission dynamics in two communities (Northeast and South) were similar to that found in Barcelona, following an initial increase and a subsequent decrease, with another mild increase in transmission before the final decrease. Two communities (North and Northwest) seemed to follow a different, more variable pattern, probably due to the smaller number of cases declared in these regions (see Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 4. MPX effective reproduction number by mobility-based community in Spain, 25 April–10 August 2022. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

While transmission across the MSM population resembled closely the global dynamics (as expected, since 75% of the patients identified themselves as MSM), the dynamics of infection across the heterosexual population seemed to be qualitatively different, with several peaks and valleys in the curve before the final decrease (Figure 5).

Figure 5. MPX effective reproduction number across the MSM and heterosexual populations in Spain, 25 April–10 August 2022. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Several factors might have contributed to the decrease in Rt. Since July, institutional and NGO campaigns have also been launched in order to increase awareness in the LGBTIQ community and to promote preventive measures, which may have caused changes in the behaviour of the at-risk population. The reduction in the susceptible population due to natural or acquired immunity may also be a relevant factor for reducing the transmission. Indeed, contact networks among MSM are known to be governed by a smaller number of individuals who concentrate on a larger proportion of contacts [32]. This relatively small group of the population may have been more exposed to the disease during the first weeks of the outbreak, acquiring immunity at a higher pace. Post-exposure vaccination to close contacts of the confirmed cases was prioritised in Spain on June 9 [33], and this recommendation was extended to pre-exposure vaccination of the most-at-risk population on July 12 [34]. However, the expected time required to develop immunity makes it unlikely for vaccination to have contributed significantly to the reduced transmission.

Transmission in Madrid and Barcelona seemed to follow different initial trends. In Madrid, it steadily decreased from an initial peak, while in Barcelona a bell-shaped curve was found for the first month of the outbreak. In addition to the different infection dynamics that may have taken place in the two provinces, the substantially higher estimates for the first days in Madrid may represent an overestimation due to the new incorporation of the disease in the surveillance system [25]. No apparent relations between the variations in these curves and the dates of events expected to be associated with a higher risk of infection were found (for instance, Madrid Pride during 1–10 July 2022), hinting towards the role of continued transmission in the spread of the outbreak (see below, however, for the limitations of this estimate).

As with any surveillance system, delays and incomplete information may occur and distort our estimates. This is particularly relevant for the first few days of the outbreak, where an exceptionally high Rt was obtained, possibly due to an accumulation of cases of a previously non-prevalent disease and the known initial overestimation of the Rt [Reference O’Driscoll, Harry, Donnelly, Cori and Dorigatti26]. A smaller value should be expected during these days, close to the basic reproduction number of the disease R0 [Reference Guzzetta, Mammone, Ferraro, Caraglia, Rapiti, Marziano, Poletti, Cereda, Vairo, Mattei, Maraglino, Rezza and Merler6, Reference Miura, van Ewijk, Backer, Xiridou, Franz, op de Coul, Brandwagt, van Cleef, van Rijckevorsel, Swaan, van den Hof and Wallinga29]. A slightly lower value for the Rt may also be found in the last few days due to possible reporting delays during a holiday period, as usual when using the method of Cori et al. [Reference Cori, Ferguson, Fraser and Cauchemez23]. Finally, some cases during the last observed days may be missing due to delayed updates in the database, as the final date of update of the data set was 23 August 2022.

The estimates for the different groupings of the population should also be interpreted with care, due to the following limiting factors. First, the notification of imported cases is not always complete. In addition to this, geographical mixing is expected to occur between the regions considered in the analysis (both between Madrid and Barcelona and the mobility-based communities). These facts could cause variations in the estimates, in particular overestimations of the effective reproduction number during the first stages of the outbreak. Finally, the variable recording the sexual orientation of the cases is subject to considerable underreporting (23% empty records; only 149 out of 6284 cases identified as heterosexual), which manifests the possible inaccuracy of the estimate found for the heterosexual population, seen also in the large confidence intervals found for this estimate. Possible mixing between the MSM and the heterosexual populations could also be overlooked in our analysis due to incomplete declaration of the previous sexual partners.

Two different estimates for the mean generation interval are available in the literature [3, Reference Guzzetta, Mammone, Ferraro, Caraglia, Rapiti, Marziano, Poletti, Cereda, Vairo, Mattei, Maraglino, Rezza and Merler6, Reference Ward, Christie, Paton, Cumming and Overton9], to our best knowledge. These were computed from 17 and 16 identified pairs of a secondary case and its primary case from the UK and Italy, respectively, and both report a wide 95% confidence interval. Interestingly, we found that the Rt decreased below 1 on the same date (July 12) when using both of these parametrisations. It would be desirable to further support our computations when estimates for this parameter computed from a larger amount of data are available. While estimates based on a larger number of cases are available for the incubation period [3, Reference Guzzetta, Mammone, Ferraro, Caraglia, Rapiti, Marziano, Poletti, Cereda, Vairo, Mattei, Maraglino, Rezza and Merler6, Reference Tarín-Vicente, Alemany, Agud-Dios, Ubals, Suñer, Antón, Arando, Arroyo-Andrés, Calderón-Lozano, Casañ, Cabrera, Coll, Descalzo, Folgueira, García-Pérez, Gil-Cruz, González-Rodríguez, Gutiérrez-Collar, Hernández-Rodríguez, López-Roa, de los Ángeles Meléndez, Montero-Menárguez, Muñoz-Gallego, Palencia-Pérez, Paredes, Pérez-Rivilla, Piñana, Prat, Ramirez, Rivero, Rubio-Muñiz, Vall, Acosta-Velásquez, Wang, Galván-Casas, Marks, Ortiz-Romero and Mitjà17, Reference Miura, van Ewijk, Backer, Xiridou, Franz, op de Coul, Brandwagt, van Cleef, van Rijckevorsel, Swaan, van den Hof and Wallinga29], a more accurate description of this parameter’s distribution is still of need.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268823000985.

Data availability statement

Data were collected by routine surveillance systems. Information is available at Instituto de Salud Carlos III’s official mpox site: https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Paginas/Resultados_Vigilancia_Viruela-del-mono.aspx. The data set analysed during the current study is available upon reasonable request from [email protected].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all Members of the National Monkeypox Response Group: Coordinating Centre for Health Alerts and Emergencies, Directorate General of Public Health, Ministry of Health: Fernando Simón, Berta Suarez Rodríguez, Bernardo R. Guzmán Herrador, Eduardo Javier Chong Chong, Sonia Fernández Balbuena, Andrés Mauricio Brandini Romersi, Cristina Giménez Lozano, Alberto Vallejo-Plaza, Gabriela Saravia Campelli, Patricia Santágueda Balader, Lucía García San Miguel, Esteban Aznar Cano; Division of Control of HIV, STI, Hepatitis and Tuberculosis, Ministerio de Sanidad, Madrid, Spain: Julia del Amo, Rosa Polo, Javier Gómez Castellá, Ana Koerting; National Centre of Epidemiology, Carlos III Health Institute: Pedro Arias; National Centre for Microbiology, Carlos III Health Institute: Maria Paz Sanchez Seco (second affiliation: CIBER in Infectious Diseases, CIBERINFEC), Ana Vázquez (second affiliation: CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Pública, CIBERESP), Patricia Sánchez (second affiliation: CIBER in Infectious Diseases, CIBERINFEC), Laura Herrero, Francisca Molero, Montserrat Torres; Immunization Programme Area, Directorate General of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Madrid, Spain: Aurora Limia, Laura Sánchez Cambronero Cejudo; Andalucía: Ministry of Health and Families of Andalusia: Nicola Lorusso, Virtudes Gallardo García, Isabel Maria Vazquez Rincon; Aragón: Dirección General de Salud Pública: Juan Pablo Alonso Pérez de Agreda, Alberto Vergara Ugarriza, Carmen Montaño Remacha; Asturias: Dirección General de Salud Pública; Gobierno de Asturias: Mario Margolles Martins, An Lieve Boone, Marta Huerta Huerta; Islas Baleares: Dirección General de Salud Pública. Antonio Nicolau Riutort, Teresa González Cortijo; Canarias: Dirección General de Salud Pública, Servicio Canario de la Salud: Álvaro Luis Torres Lana, Araceli Alemán Herrera, Isabel Falcón García, Laura García Hernández, Oscar-Guillermo Pérez Martín; Cantabria: Public Health Observatory of Cantabria, Cantabria, Spain: Adrian Hugo Aginagalde Llorente Cataluña: Public Health Agency of Catalonia: Ana Martinez Mateo, Jacobo Mendioroz Peña, Manuel Valdivia Guijarro, Gemma Rosell Duran; Ceuta: Consejería de Sanidad, Consumo y Gobernación: Ana Isabel Rivas Pérez, Violeta Ramos Marín; Castilla la Mancha: Servicio de Epidemiología de Castilla la Mancha: Pilar Peces Jiménez, M. Remedios Rodolfo Saavedra; Castilla y León: Dirección General de Salud Pública: Maria del Carmen Pacheco Martinez, Socorro Fernández Arribas, Henar Marcos Rodríguez, Nuria Rincón Calvo, Virginia Alvarez Rio, Natalia Gutierrez Garzón, Isabel Martínez-Pino (second affiliation: CIBER in Epidemiology and Public Health, CIBERESP, Madrid, Spain), M. Jesús Rodríguez Recio; Comunidad Valenciana: Subdirección General de Epidemiología, Vigilancia de la Salud y Sanidad Ambiental: Francisco Javier Roig Sena, Rosa Carbó Malonda; Extremadura: Dirección General de Salud Pública, Servicio Extremeño de Salud: Juan Antonio Linares Dópido, María del Mar López-Tercero Torvisco; Galicia: Dirección Xeral de Saúde Pública, Consellería de Sanidade, Xunta de Galicia, Santiago, Spain: Maria Teresa Otero Barrós; Sección de Epidemioloxía; Xefatura Territorial de Sanidade, A Coruña: M. del Carmen García Bañobre, Sección de Epidemioloxía. Xefatura Territorial de Sanidade, Pontevedra: M. del Pilar Sánchez Castro, Sección de Epidemioloxía. Xefatura Territorial de Sanidade, Ourense: Miriam Rebeca Martínez Soto; Madrid: Dirección General de Salud Pública. Elisa Gil Moltalban, Marcos Alonso García, Fernando Martin Martínez, M Jose Domínguez Rodríguez, Laura Montero Morales, Ana Humanes Navarro, Esther Cordoba Deorador, Antonio Nunziata Forte, Alba Nieto Julia, Noelia Cenamor Largo, Carmen Sanz Ortíz, Natividad García Marín, Jesús Sánchez Díaz, Mercedes Belen Rumayor Zarzuelo, Nelva Mata Pariente, Jose Francisco Barbas del Buey, Manuel Jose Velasco Rodríguez, Andrés Aragón Peña, Elena Rodríguez Baena, Angel Miguel Benito, Ana Perez Meixeira, Jesus Iñigo Martinez, María Ordobas, Araceli Arce; Murcia: Department of Epidemiology, Regional Health Council, IMIB-Arrixaca: Alonso Sánchez-Migallón Naranjo; Melilla: Consejería de Políticas Sociales, Salud Pública y Bienestar Animal: Daniel Castrillejo; Murcia: Regional Health Council, IMIB-Arrixaca, Murcia University: Maria Dolores Chirlaque López; Navarra: Instituto de Salud Pública de Navarra, and Navarre Institute for Health Research (IdiSNA): Manuel García-Cenoz, Jesús Castilla (third affiliation: CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Pública, CIBERESP), Itziar Casado (third affiliation: CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Pública, CIBERESP), Cristina Burgui (third affiliation: CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Pública, CIBERESP), Nerea Egües, Guillermo Ezpeleta; País Vasco: Departamento de Salud del Gobierno Vasco; Subdirección de Salud Pública y Adicciones de Gipuzkoa: Fernando González Carril, Olatz Mokoroa Carollo (second affiliation: Instituto de investigación Sanitaria Biodonostia); Departamento de Salud del País Vasco, Subdirección de Salud Pública y Adicciones de Araba; Vitoria-Gasteiz: Etxebarriarteun Aranzabal, Larraitz; Departamento de Salud del País Vasco Subdirección de Salud Pública y Adicciones de Bizkaia; Esther Hernandez Arricibita;

La Rioja: Dirección General de Salud Pública, Consumo y Cuidados: Eva María Martínez Ochoa, Ana Carmen Ibáñez Pérez.

Author contribution

D.G-G., D.G-B., V.H., and A.D. drafted the manuscript. D.G-G. and D.G-B. conducted the analysis. M.R-A., V.H., L.S., and M.S. were responsible for the management of the mpox surveillance, data collection, and quality control. M.J.S. and P.G. revised the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research was partially supported by CIBER (Strategic Action for Monkeypox) – Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red – (CB 2021), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Unión Europea – NextGenerationEU.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.