Ultimately, the criminal justice system and those writing about the issue of rape have dealt poorly with the issue of false allegations. Given the legal and societal prominence of this subject, it is a failure that should be addressed.

—Reference RumneyPhilip N.S. Rumney (2006: 158)In June 2010, the Baltimore Sun reported that the Baltimore Police Department led the country in the percentage of rape cases that were deemed to be false or baseless and thus were unfounded. According to the report, from 2004 to 2009 about a third of the rapes reported to the police department were unfounded, a rate three times the national average. Also in June 2010, The New York Times reported that New York Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly had appointed a task force to look into the handling of rape complaints and to recommend new training protocols for dealing with victims of sexual assault. The review was prompted by complaints from rape victims, who said that their allegations of sexual assault were unfounded or downgraded to misdemeanors. These news stories—along with others regarding the mishandling of rape cases in Milwaukee, Cleveland, New Orleans, and Philadelphia—culminated in a September 2010 U.S. Senate Hearing convened by Senator Arlen Specter to examine the systematic failure to investigate rape on the part of police departments nationwide. Testifying at the hearing was Carol E. Tracey, executive director of the Women's Law Project, who said, “It's clear we're seeing chronic and systemic patterns of police refusing to accept cases for investigation, misclassifying cases to noncriminal categories so that investigations do not occur, and ‘unfounding’ complaints by determining that women are lying about being sexually assaulted.”

Allegations that “women are lying about being sexually assaulted” are not new. In fact, Sir Matthew Hale, an English judge, opined in the seventeenth century that rape “is an accusation easily to be made and hard to be proved, and harder to be defended by the party accused, tho never so innocent” (Hale 1736, reprinted Reference Hale and Emlyn1971; but see Reference BelknapBelknap (2010) for a rejoinder). Estimates of the rate of false reports vary widely, with some researchers concluding that the rate is 30–40 percent (Reference JordanJordan 2004; Reference KaninKanin 1994) or higher (see Reference RumneyRumney 2006) and others finding that the rate is 2 percent or lower (Reference BrownmillerBrownmiller 1975; Kelly, Lovett, & Reference Kelly, Lovett and ReganRegan 2005; Reference Theilade and ThomsenTheilade & Thomsen 1986). Noting that those who work in the field of sexual violence are continually asked to comment on the number of reports of rape that are false, Reference LonswayLonsway (2010: 1358) stated that recent research findings from studies that use appropriate research designs suggest that the rate of false allegations is low and concluded that “there is simply no way to claim that ‘the statistics are all over the map.’ The statistics are actually now in a very small corner of the map.” According to Reference Lonsway, Archambault and LisakLonsway, Archambault, and Lisak (2009: 2), the more methodologically rigorous research finds that the percentage of false reports ranges from 2 to 8 percent.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate sexual assault cases that were unfounded by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) in 2008. Using qualitative and quantitative data from redacted police case files and from interviews with LAPD detectives, we determine whether the cases that were unfounded involved false allegations and identify the factors that predict unfounding. We begin with a review of research on the prevalence of false allegations of rape and the decision to unfound the charges.

Literature Review: False Allegations and Unfounding Decisions

One of the most controversial—and least understood—issues in the area of sexual violence is the prevalence of false reports of rape, which Reference LonswayLonsway (2010: 1356) referred to as “the elephant in the middle of the living room.” As noted above, estimates of the number of false reports vary widely. This reflects a lack of conceptual clarity (Reference SaundersSaunders 2012), a confounding of police decisions to unfound and false reports, and inappropriate research strategies. Many researchers (Reference JordanJordan 2004; Reference KaninKanin 1994) either did not explicitly explain how they defined a false rape allegation or used a definition that is inconsistent with policy statements by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP). FBI guidelines on clearing cases for Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) purposes state that a case can be unfounded only if it is “determined through investigation to be false or baseless” (UCR Handbook 2004: 77). The Handbook also stresses that police are not to unfound a case simply because the complainant refused to prosecute or they are unable to make an arrest. Similarly, the IACP (2005: 12) policy on investigating sexual assault cases states that “the determination that a report of sexual assault is false can be made only if the evidence establishes that no crime was committed or attempted” and that “this determination can be made only after a thorough investigation.” Both sources, in other words, emphasize that the police must conduct an investigation and that their investigation must lead them to a conclusion that a crime did not occur.

A related problem concerns the assumption that rape cases unfounded by the police are, by definition, false allegations. There are two problems with this. First, UCR guidelines state that a case can be unfounded if it is “false or baseless” (emphasis added). Although sometimes used interchangeably, these terms—false and baseless—do not mean the same thing. According to Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. (2010: 1321), a report is false if “the victim deliberately fabricates an account of being raped”; it is baseless if “the victim reports an incident that, while truthfully recounted, does not meet … the legal definition of a sexual assault.” Consider a case in which a complainant, believing that “something happened” while she was passed out at a party, reports a rape to the police but the investigation conducted by the police uncovers no forensic or other evidence that a crime was committed; the victim's allegation would be baseless, but not deliberately false.

The second problem with conflating unfounding with false allegations is that researchers have documented that police unfound sexual assault reports inappropriately; they categorize as unfounded allegations involving complainants who engaged in risky behavior at the time of the incident, complainants who were unwilling to cooperate in the prosecution of the suspect, complainants who delayed reporting, or complainants whose allegations were inconsistent or contradictory (Reference Kelly, Lovett and ReganKelly, Lovett, & Regan 2005; Reference KerstetterKerstetter 1990; Reference KonradiKonradi 2007; Reference SaundersSaunders 2012). If a police agency is using unfounding to dispose of problematic—but not false—cases, assuming that all unfounded cases are false allegations is obviously misleading (Reference BelknapBelknap 2010). This was confirmed by Reference SaundersSaunders (2012), who interviewed police and prosecutors in the United Kingdom, finding that respondents used the term “false allegation” to refer to both false complaints and false accounts of sexual assault. As she noted (2012: 1168), the police and prosecutors she interviewed defined the false allegation not as “a complete fabrication of something that never happened,” but as “an allegation containing falsehoods: a generic, all-encompassing definition capable of incorporating both the rape that did not happen (the false complaint) and the rape that did not happen in the way the complainant said it did (the false account)” (emphasis in the original). Clearly, these discrepancies in the ways that false reports are defined by researchers and practitioners raise questions about the reliability of official unfounding statistics.

A third problem plaguing research on false rape reports is that many studies simply rely on the classifications made by law enforcement agencies (Reference Harris and GraceHarris & Grace 1999; Reference KaninKanin 1994). That is, they take at face value the conclusion of law enforcement that a complaint is false or baseless and therefore should have been unfounded. As Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. (2010: 1322) note, studies that rely on law enforcement categorizations “are unable to determine whether those classifications adhere to IACP and UCR guidelines and whether they are free of the biases that have frequently been identified in police investigation of rape cases.”

Although the prevalence of these definitional and methodological problems calls the findings of much of the extant research on false rape reports into question (Reference BelknapBelknap 2010; Reference RumneyRumney 2006), there are a number of recent studies that use more appropriate research designs and thus provide more credible estimates of the number of false reports. For example, a British Home Office study (Reference KellyKelly 2010; Kelly, Lovett, & Reference Kelly, Lovett and ReganRegan 2005) of case attrition in rape cases used multiple sources of data to analyze cases that were “no-crimed” (equivalent to unfounding in the United States) by the police. The researchers found that cases in the “no crime” group included both false allegations, which constituted about 8 percent of the rape cases reported to the police, and cases in which there was no evidence of an assault (which included both cases that were reported by a third party and cases involving complainants who had no memory of an assault but reported to the police because they feared that “something” had happened). In about half of the cases that were designated as false reports, the information provided by the police contained an explanation for why the complaint was deemed to be false—in 53 of the cases the complainant admitted that the allegation was false, in 28 the complainant retracted the allegation, in 3 the complainant refused to cooperate in the investigation, and in 56 the police determined that the complaint was false based on the lack of evidence (Reference KellyKelly 2010: 1349).

Because the authors' review of the case files revealed that policy statements regarding false complaints were not always being followed, they coded the complaints designated by the police as false allegations as either “probable,” “possible,” or “uncertain.” They then excluded the cases that were coded “uncertain” (i.e., cases “where it appeared victim characteristics had been used to impute that they were inherently less believable”) and recalculated the rate of false reports to be 3 percent of all cases reported to the police. The authors of the study concluded that “a culture of suspicion remains, accentuated by a tendency to conflate false allegations with retractions and withdrawals, as if in all such cases no sexual assault occurred” (Reference KellyKelly 2010: 1351).

Similar conclusions were reached by Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. (2010), who analyzed case summaries of every sexual assault reported to the police department of a major university in the Northeastern United States from 1998 to 2007 (N = 136). The author and three coinvestigators used the IACP guidelines to independently determine whether a report was false. A complaint was categorized as a false report “if there was evidence that a thorough investigation was pursued and that the investigation yielded evidence that the reported sexual assault had in fact not occurred” (Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. 2010: 1328). The research team concluded that only 8 of the 136 cases (5.9 percent) were false reports; these eight cases were also designated as false reports by police investigators. In three of these cases the complainant admitted that the report had been fabricated, in one the complainant provided a partial admission of fabrication and there was other evidence that a crime did not occur, in three the complainant did not admit that the allegation was fabricated but the police investigation produced evidence that the crime did not occur, and in a final case the complainant recanted but evidence that the allegation was fabricated was ambiguous. Lisak et al. (2010: 1329) concluded that the results of their study “are consistent with those of other studies that have used similar methodologies to determine the prevalence of false rape reporting.”

In summary, there is very limited research on false rape allegations and unfounding decisions, and the research that does exist suffers from a number of limitations. The unfounding research is dated and much of the research on false reports is based on inappropriate or inconsistent definitions. Although the studies of Reference Kelly, Lovett and ReganKelly, Lovett, and Regan (2005; see also Reference KellyKelly 2010) and Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. (2010) help fill a void in the literature, neither provides definitive answers to questions regarding the prevalence of false rape reports. Kelly and her colleagues examined complaints reported to the police in England and Wales and it is questionable whether their results can be generalized to the United States. The generalizability of Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al.'s (2010) findings is also called into question, given that they examined rapes reported to a university police department. Another limitation of this study is that the authors did not have access to the complete case files; rather, the police department provided case summaries and the research team met with officials from the department, who brought the case files with them and who referenced the files if questions arose regarding the appropriate categorization of a case. As Reference BelknapBelknap (2010: 1339), who admitted that the Lisak et al. study “did fill a void,” argued, a major problem with the study was “discerning the accuracy of the police interpretations of whether a reported rape was false.” Given that prior research has established that police use the unfounding decision inappropriately to dispose of problematic—but not false or baseless—sexual assault reports, this obviously is a cause for concern.

Theoretical Perspectives on Police Decisionmaking

Research on police unfounding decisions—indeed, research on police decisionmaking generally—is somewhat atheoretical. Reference BlackBlack (1976, Reference Black1980, Reference Black1989) contended that police decisionmaking, including the decision to unfound, “is predictable from the sociological theory of law,” which holds that the quantity of law applied in any particular situation depends on factors such as the social status of those involved, the relational distance between the parties, and the degree of informal social control to which the parties are subjected. In discussing the investigation of crimes by detectives, Reference BlackBlack (1980) argued that the amount of time and energy that will be devoted to a case will depend not only on the seriousness of the crime, but also on the social status, background, reputation, and credibility of the victim and suspect.

Another theoretical perspective applicable to police handling of sexual assault complaints is the focal concerns perspective (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998). Although this perspective was developed to explain judges' sentencing decisions, it has also been applied to prosecutors' charging decisions (see, e.g., Reference Spohn, Beichner and Davis-FrenzelSpohn, Beichner, & Davis-Frenzel 2001) and, as we explain below, is also relevant to police decisionmaking. According to this perspective, judges' sentencing decisions are guided by three focal concerns: their assessment of the blameworthiness of the offender; their desire to protect the community by incapacitating dangerous offenders or deterring potential offenders; and their concerns about the practical consequences, or social costs, of sentencing decisions. The first focal concern—offender blameworthiness—reflects judges' assessments of the seriousness of the crime, the offender's prior criminal record, and the offender's motivation and role in the offense. By contrast, the second focal concern—protecting the community—rests on judges' perceptions of the dangerousness and threat posed by the offender and the offender's likelihood of recidivism. Judges' concerns about the practical consequences or social costs of sentencing decisions reflect their perceptions regarding the offender's ability “to do time” and the costs of incarcerating offenders with medical conditions, mental health problems, or dependent children, as well as their concerns about maintaining relationships with other members of the courtroom workgroup and protecting the reputation of the court.

We suggest that the focal concerns that guide police decisionmaking in sexual assault cases are similar, but not identical, to those that guide judges' sentencing decisions. Like judges (and prosecutors), police officers consider the seriousness of the crime, the degree of injury to the victim, and the blameworthiness and dangerousness of the offender. They are also concerned about the practical consequences or social costs of their decisions, but, like prosecutors, their concerns focus more on the likelihood of conviction than the costs of incarceration. Although, technically, police decisions to unfound the report or arrest the suspect do not rest on an assessment of convictability, as a practical matter the police do take this into consideration. They view the decision to arrest as the first step in the process of securing a conviction in the case; as a result, they are reluctant to make arrests that are unlikely to lead to the filing of charges against the suspect. We suggest that this concern with convictability creates what Reference FrohmannFrohmann (1997: 535) refers to as a “downstream orientation” to decision makers who will handle the case at subsequent stages of the process. Whereas Reference FrohmannFrohmann (1997), whose work focused on charging decisions in sexual assault cases, argued that prosecutors consider how the judge, jury, and defense attorney will react to the case, we contend that the downstream orientation of detectives investigating sexual assault cases is to the prosecutors who make filing decisions. That is, detectives attempt to predict how prosecutors will assess and respond to the case. Because prosecutors' assessments of cases are based on a standard of convictability that encourages them “to accept only ‘strong’ or ‘winnable’ cases for prosecution” (Reference FrohmannFrohmann 1991: 215), this means that detectives' decisions similarly will reflect their assessment of the likelihood of conviction should an arrest be made. In sexual assault cases, in which the victim's testimony is crucial, these assessments rest squarely on an evaluation of the victim's credibility. As a result, if the victim's allegations are inconsistent or do not comport with detectives' “repertoire of knowledge” (Reference FrohmannFrohmann 1991: 217) about the typical sexual assault or if the detective believes that the victim has ulterior motives for reporting the crime or will not cooperate as the case moves forward, the odds of unfounding will increase and the likelihood of arrest will decrease.

Both the sociological theory of law and the focal concerns perspective suggest that the “social structure” (Reference BlackBlack 1989) of the case influences how the case will be handled. As Reference BlackBlack (1989: 21) put it, “the handling of a case always reflects the social characteristics of those involved in it.” Similarly, the focal concerns perspective holds that the limited information available about the case, especially at early stages in the process, means that “decision makers rely on attributional decision-making processes that invoke societal stereotypes” (Reference Johnson and BetsingerJohnson & Betsinger 2009: 1055). In the context of police decisionmaking generally and the unfounding process specifically, these perspectives suggest not only that the social status of the complainant and suspect will be influential, but that stereotypes of “real rapes” (Reference EstrichEstrich 1987) and “genuine victims” (Reference LaFreeLaFree 1989) will also play a role. Thus, the decision to unfound the report (as either false or baseless) will be based on a combination of factors related to crime seriousness and victim credibility. These perspectives suggest that unfounding will be less likely if the crime is serious, the victim and suspect are strangers, the victim was injured, the victim's allegations are consistent with detectives' “typifications of rape scenarios” (Reference FrohmannFrohmann 1991: 217), and the victim is viewed as credible and without ulterior motives for making allegations against the suspect.

Research Questions

Our study, which builds on and extends existing scholarship on false allegations of rape and unfounding decisions, responds to Reference RumneyRumney's (2006: 155; see also Reference SaundersSaunders 2012) call for “research that examines how and why police officers determine that particular allegations are false.” We examine the case files for a sample of sexual assault cases investigated by the LAPD in 2008 to determine whether the complaints unfounded by the police were correctly classified as false or baseless reports and to estimate the prevalence rate for false reports for one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the United States. We also use detailed quantitative and qualitative data to identify the factors that predict unfounding and the decision-making criteria that LAPD detectives use in deciding to unfound a rape complaint. Our research on this issue is guided by an integrated theoretical perspective that incorporates propositions from Reference BlackBlack's (1989) sociological theory of law and Steffensmeier, Ulmer, and Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerKramer's (1998) focal concerns theory.

Research Design and Methods

We use a mixed methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative data from case files and qualitative data from interviews with detectives assigned to investigate allegations of sexual assault. We selected a stratified random sample (N = 401) of sexual assaults involving female complainants over the age of 12 which were reported to the LAPD in 2008Footnote 1 to identify predictors of sexual assault cases that were unfounded. Because we wanted to ensure an adequate number of cases from each LAPD division, as well as an adequate number of cases from each case clearance category (cleared by arrest, cleared by exceptional means, investigation continuing, and unfounded), the sample was stratified by LAPD division and, within each division, by the type of case clearance.Footnote 2 To determine whether unfounded complaints were in fact false or baseless allegations, we analyze quantitative and qualitative data on 81Footnote 3 complaints that the LAPD unfounded in 2008.

The data for this project were extracted from case files that were provided by the LAPD and from which all information that could be used to identify the complainant, the witnesses, the suspect, or the law enforcement officers investigating the case was redacted. The LAPD provided the researchers with the complete case file for every case in the sample. The case files were very detailed and included the crime report prepared by the patrol officer who took the initial report from the complainant, all follow-up reports prepared by the detective to whom the case was assigned for investigation, and the detective's reasons for unfounding the report. The case files also included either verbatim accounts or summaries of statements made by the complainant, by witnesses (if any), and by the suspect (if the suspect was interviewed); a description of physical evidence recovered from the alleged crime scene, and the results of the forensic medical exam of the victim (if the victim reported the crime within 72 hours of the alleged assault).

We supplement the data from case files with information gleaned from interviews with LAPD detectives who had experience investigating sexual assaults.Footnote 4 During June and July 2010, we interviewed 52 LAPD detectives.Footnote 5 During the interviews, which typically lasted about 1 hour, we asked respondents a series of questions regarding the decision to unfound the report: the standards they use in making this decision, whether complainants have to recant the allegations in order to unfound the report, whether certain types of cases have a higher likelihood of being unfounded than others, and whether officers ever unfounded a case for reasons other than a belief that a crime did not occur. Respondents also were asked how they determined whether the report was false or not.

In the next two sections, we discuss the methods that were used to achieve each of the study's objectives and the findings relevant to each objective.

Unfounding and False Reports

Categorizing Cases as False or Baseless

The first objective of this study is to determine if the sexual assault cases unfounded by the LAPD were, in fact, false or baseless, and to calculate the prevalence rate of false reports. To determine whether the allegation was a false report, the cases were analyzed using a form of modified analytic induction (Reference HolstiHolsti 1969; Reference PattonPatton 2002). Following Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. (2010), we define a false report as a report that was deliberately fabricated by the victim, and a baseless report as a report that does not meet the legal definition of rape, but the victim did not deliberately lie about being raped. Consistent with both FBI guidelines for clearing cases and with the IACP model policy on investigating sexual assault cases, we categorized a case as a false report only if a thorough investigation led the police to conclude that the allegation was false and that no crime occurred. In order to categorize a complaint as a false report, in other words, the case file had to include evidence indicating that the complainant deliberately fabricated the allegation of sexual assault. We categorized as “baseless” cases that were unfounded by the police after an investigation revealed that no crime occurred, but there was no evidence that the complainant intentionally lied about the incident.

Each case file was carefully reviewed by the three coauthors, who then independently categorized the report as a false report, a baseless report, not a false report, or a case in which it was not clear whether the report was false or not. Within the “false report” category, cases were subdivided into (1) cases in which the complainant recanted and there was evidence to support a conclusion that a crime did not occur and (2) cases in which the complainant did not recant but there was either evidence that the crime did not occur or no evidence that the crime did occur. Regardless of whether the complainant recanted, we looked for evidence that would support a conclusion that a crime did not occur: witness statements, video evidence, or physical evidence that clearly contradicted the complainant's statement. In one case, for example, the complainant reported that she was abducted from a fast-food restaurant's parking lot, but video surveillance cameras did not record anyone being abducted during the time frame provided by the complainant. In another case, the complainant stated that she called 911 and reported that she had been sexually assaulted, but there was no record of the call. There were also a number of cases in which the complainant had mental health issues, and family members or witnesses stated that she was not being truthful or there was evidence that she made false reports in the past.

The second category of unfounded cases is cases that were determined to be baseless; that is, there was no evidence that a crime occurred but the complainant did not deliberately fabricate the account. Included in this category are cases in which complainants believed that they might have been sexually assaulted when they were under the influence of drugs or alcohol; these cases were unfounded when the forensic medical exam revealed no physical evidence of a sexual assault or witnesses testified that an assault did not occur.

The “not a false report” category was subdivided into (1) cases in which the complainant recanted but there was evidence that her recantation was motivated by fear of retaliation by the suspect, pressure from the suspect or the suspect's family or friends, or lack of interest in proceeding with the case, and (2) cases in which the complainant did not recant, there was evidence that the crime did occur but that prosecution would be unlikely because of the complainant's behavior at the time of the incident, the complainant's lack of cooperation, lack of corroboration of or inconsistencies in the complainant's statement, and these factors were noted by the investigating officer as reasons for unfounding. The cases that fell into the “not clear whether the report was false or not” category included cases that the research team believed should have been investigated further before making a decision regarding case clearance, and cases which the researchers could not categorize. After independently categorizing the cases, the researchers met to review their decisions and to discuss in more detail the few cases (N = 8) in which there was disagreement about the way the case should be categorized. The interrater reliability for these 81 cases was 90.1 percent.

We want to emphasize that we did not assume that complainants who recanted their testimonies had filed a false report. We assumed, like Reference RaphaelRaphael (2008: 371), that “just because the victim recants does not mean that the abuse did not happen.” A case in which the complainant recanted was categorized as a false report only if there was independent evidence that a crime did not occur and there was no indication in the case file that the complainant's recantation was motivated by fear, pressure, or a belief that prosecution would not be in her best interest.

Findings: False and Baseless Reports

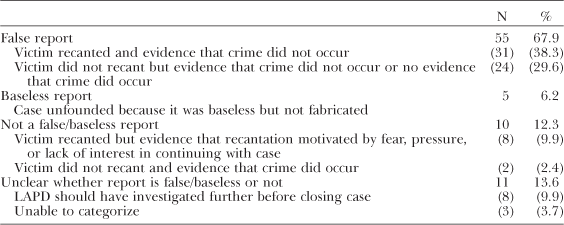

As shown in Table 1, we categorized two-thirds (67.9 percent) of the unfounded cases as false reports, either because the complainant recanted and there was evidence that a crime did not occur (N = 31; 38.3 percent) or because there was evidence that the crime did not occur or no evidence that the crime did occur, even though the complainant did not recant (N = 24; 29.6 percent). An additional five cases were determined to be baseless, but not false. Only 10 cases were deemed not to be false reports; eight of these were cases in which the complainant recanted but there was evidence that her recantation was motivated by fear, pressure, or a lack of interest in moving forward with the case, and only two were cases in which the complainant did not recant and there was evidence that a crime did, in fact, occur. We were unable to categorize the remaining 11 cases as false reports or not; eight of these cases were cases where the research team concluded that the LAPD should have investigated further prior to making a decision regarding the appropriate case closure.

Table 1. Cases Unfounded by the LAPD (N = 81)—False Reports or Not?

One conclusion that can be drawn from these data is that the LAPD is clearing sexual assault cases as unfounded appropriately most, but not all, of the time. Stated another way, three quarters (74.1 percent) of the cases that were cleared as unfounded were cases in which there was evidence that a crime did not occur and that the complainants, for various reasons (for a discussion of motivations for filing false reports, see Reference O'Neal, Spohn, Tellis and WhiteO'Neal et al., in press), either filed false reports of sexual assault or sexual battery (false allegations), or reported a rape because they believed that they had been assaulted while under the influence of drugs or alcohol (baseless allegations). Although there were some cases that appeared to require additional investigation before clearing, there were only 10 cases where we concluded that a crime did occur and therefore the case should not have been unfounded. These data also reveal that recantation of the complainant is not required to unfound the case. Of the 81 cases that were unfounded, only 45 (55.6 percent) were cases in which the complainant recanted.

Because the 81 unfounded cases are not a random sample of all cases reported to the LAPD in 2008, we cannot use the unweighted data to determine the proportion of all 2008 reports that were false reports. To determine this, we used data that were weighted by the proportion of cases from each division and, within each division, the proportion of cases from each case closure type.Footnote 6 Using these data, we determined that 4.5 percent of all cases reported to the LAPD in 2008 were false reports; 2.2 percent were cases in which the complainant recanted and there was evidence that a crime did not occur; and 2.3 percent were cases in which the complainant did not recant but there was evidence that a crime did not occur. This is consistent with Reference Lonsway, Archambault and LisakLonsway, Archambault, and Lisak's (2009: 2) conclusion that although one cannot know with any degree of certainty how many sexual assault reports are false, “estimates narrow to the range of 2–8 percent when they are based on more rigorous research of case classifications using specific criteria and incorporating various protections of the reliability and validity of the research.”

In the sections that follow, we provide qualitative data to illustrate the types of cases in each category.

Unfounded Cases That Were False Reports

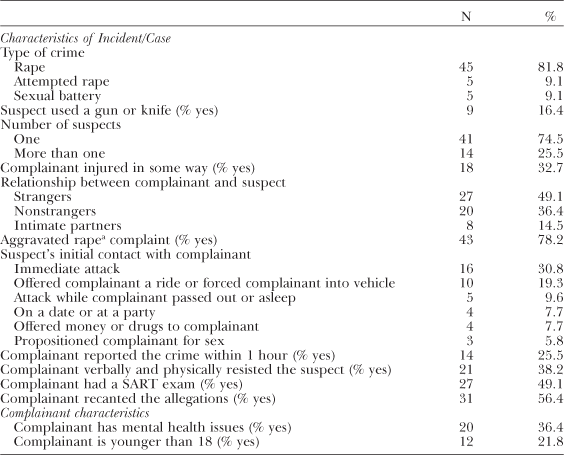

Descriptive statistics on the 55 unfounded cases deemed to be false reports are presented in Table 2. In all but 10 of these cases, the complainant reported that she had been raped; only five cases involved attempted rape and only five were reports of sexual battery (i.e., fondling or touching the complainant). In most cases, the complainant did not report that the suspect used a gun or knife, but in one-fourth the complainant stated that she had been attacked by more than one suspect, and in a third the complainant stated that she had been injured during the assault. Half of the allegations involved suspects who were strangers to the complainant. We used these descriptive data to determine the number of false reports that were allegations of aggravated rape; that is, allegations of rape in which the victim claimed that she was attacked by a stranger, the suspect used a gun or knife, she was attacked by more than one suspect, or she suffered from collateral injuries in the attack (for a discussion of the concept of aggravated rape, see Reference EstrichEstrich 1987; Reference Kalvin and ZeiselKalvin & Zeisel 1966). We found that more than three quarters of the false reports involved allegations of aggravated rape. This suggests that complainants who file false reports believe that their accounts will be more credible if they conform to the stereotype of a “real rape.”

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics: Cases Categorized as False Reports (N = 55)

a An aggravated rape complaint is an allegation of forcible rape that involved a suspect who used a gun or a knife, more than one suspect, or collateral injury to the victim (see Estrich Reference Estrich1987).

There was little consistency in complainants' accounts of the suspects' initial contact with them: In 16 cases it was described as an immediate attack and in 10 the complainant stated that she was offered a ride or forced into a vehicle. Other complainants stated that they were attacked while asleep or passed out, that they encountered the suspect on a date or at a party, or that the suspect approached them by offering money or drugs or by propositioning them for sex. Most complainants did not report the alleged crime within 1 hour, but a third of them indicated that they resisted the suspect both verbally and physically. About half of the complainants underwent a forensic medical exam and more than half eventually recanted the allegations. Twenty of the 55 complainants had mental health issues and 12 were under the age of 18.

Although these descriptive statistics provide an overview of the types of false reports handled by the LAPD, a more detailed picture can be painted using the qualitative data from the case files. In one case, for example, the complainant told the police that she was walking alone at 2:30 in the afternoon when a white van pulled up alongside her and the driver asked her if she needed a ride. She said that she did and got in the vehicle. The suspect then parked the van under a freeway overpass where he “brandished a knife and said, ‘bad things will happen if you don't cooperate. Pull your underwear down.’ Thinking that she did not have a choice, she cooperated.” The complainant subsequently told her therapist that she had been sexually assaulted and her therapist insisted that she report the crime to the police. The investigating officer took the complainant to the alleged crime scene, pointed out the camera that was located there, and told her that they would be able to get the suspect's license plate number from the video footage. At this point, the complainant admitted that the incident was fabricated. She told the officer that she “sometimes initiates sexual liaisons with older men when she is depressed and that was the case in this incident.” She said that all of the sex acts were consensual, no force or weapon was used, and she reported the incident to her therapist to garner sympathy.

In this case, the complainant recanted her allegations of sexual assault when it became clear that the police would be able to identify the suspect's car using video footage from the alleged scene of the crime. The complainant told the police that the suspect was a stranger and stated that she did not know his name or where he lived, but apparently realized that the consensual nature of her encounter with the suspect would be revealed if the police contacted the suspect.

As noted above, just over half of the cases labeled as false reports involved complainants, like the one in the previous case, who recanted their allegations. In the next case, the complainant did not recant but there was no evidence that a crime occurred. The complainant, who was homeless, stated that she was sleeping in her car, a Honda Civic, and at some point during the night she woke up with two naked men in the car with her. She said that they drugged her with the “date rape drug” and that both suspects then penetrated her with their penises. She also said that this has happened several times before with the same suspects, but she did not report those incidents. She indicated that she did not know their names or where they lived, but that she could identify them if she saw them again. The forensic medical exam did not reveal any findings consistent with the complainant's account of forced sexual intercourse.

In the explanation for why this case was unfounded, the investigating officer wrote:

Based on the totality of the circumstances in this case, including a lack of medical evidence, victim's lack of memory, victim's claim of prior unreported incidents with the same suspects, the physical challenge of a 6′2″ and a 5′11″ suspect assaulting the victim in a Honda Civic, the victim's unresponsiveness to contact efforts, and a total lack of any evidence to corroborate the victim's unsupported allegation, there is no corpus of a crime and this report is unfounded.

We categorized this case as a false report based on the implausibility of the complainant's assertion that she was sexually assaulted by two tall naked men in a small compact car, the lack of any physical evidence to support her allegations of being drugged or sexually assaulted, and the fact that she alleged that the same thing had happened several times in the past.

Unfounded Cases That Were Baseless

Our review of the case files revealed only five unfounded cases that were baseless. These cases did not involve deliberate fabrications by the complainant; rather, the complainants suspected that they had been sexually assaulted or that “something” had happened to them. One complainant stated that she was raped while under the influence of drugs at a rave concert, a second reported that she was sexually assaulted after she and a friend left a club with two men who offered to drive them home but who instead took them to an apartment and plied them with drinks, and the third claimed that someone at the drug rehabilitation facility where she was staying raped her while she was sleeping. In the other two cases, the complainants were developmentally delayed and did not appear to understand the concept of rape.

In the first case, the 18-year-old complainant stated that she smoked marijuana and took two ecstasy pills while attending a rave concert. She said that while she was on the dance floor, a man walked up to her, sprayed her in the eyes with some type of liquid, and said, “I had a mask on, so she doesn't know it was me.” She said that people were staring at her and stated, “I felt weird. I think someone did something to me. I think that someone raped me.” She said that she did not remember having sexual intercourse with anyone, but thought that she might have blacked out, and that she decided to report the crime “just to be on the safe side.” The investigating officer interviewed the victim's friend, who was with her at the concert; she told the officer that she was “100 percent positive that XXXX was not sexually assaulted at any time while we were at the rave.” Because the complainant believed that she might have been sexually assaulted and did not intentionally fabricate the assault, we categorized the case as baseless rather than false. The other four cases categorized as baseless were very similar.

Unfounded Cases That Were Not False or Baseless Reports

As noted above, most of the 10 cases that we determined as not false or baseless reports were cases in which the complainant recanted, but it was clear that her recantation was motivated by fear of reprisal from the suspect, pressure from the suspect or his family or friends, or her lack of interest in pursuing prosecution of the suspect. For instance, one case involved an allegation of sexual assault against a physician; the complainant recanted the allegation but the investigating officer noted in the follow-up report that she did so only after being told that the suspect would go to jail if he was identified and prosecuted. In another case, the complainant told the investigating officer that the suspect, a friend from school, threatened her with a knife and said, “you better not tell anyone ‘cause my homies will get you and I know where you stay.” Although the complainant did eventually recant and told the police that no one had threatened her or coerced her to change her story, we categorized this case as “not a false report” based on the fact that the complainant gave a very clear account of the incident, used the same words to describe the incident to the patrol officer and the investigating officer, and appeared to be concerned that the suspect would get in trouble. Moreover, the investigating officer presented the case to the district attorney for a pre-arrest filing decision, which suggests that the officer may have believed the victim had been assaulted.

One of the more troubling unfounded cases that we categorized as not a false report involved a complainant who stated that she was assaulted by a man she had been dating for 3 months, but did not call the police “because she was afraid of the suspect and his threat that he would have someone kill her if she did.” The complainant eventually recanted her testimony. We categorized this case as “not a false report” for several reasons, the most important of which was the fact that there was corroboration of the complainant's allegation of sexual assault: The forensic medical exam revealed physical evidence consistent with the complainant's allegation of forced anal intercourse and the complainant made a fresh complaint to a witness, who identified the suspect as the person who assaulted the complainant. The fact that the suspect hit the complainant and threatened to kill her if she told the police that he sexually assaulted her suggests that the complainant's recantation was motivated by fear of the suspect. This is confirmed by the fact that the complainant told the police that she did not call them when the suspect fell asleep because she was afraid of him.

Unfounded Cases That Should Have Been Investigated Further

There were eight cases that the research team believed should have been investigated further. We believed that the evidence in these cases was ambiguous and that the officer should have continued the investigation until these ambiguities could be clarified. Although a number of these cases involved complainants who were under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time of the alleged assault, most also involved witnesses who might have been able to corroborate the complainant's allegations but who were never interviewed. Several of the cases involved complainants whose allegations appeared credible, but who either could not be located or decided that they did not want to proceed with the case. There were no identified suspects in any of these eight cases. Considered together, these case characteristics suggest that the complaints were unfounded because the officers investigating them believed that a suspect was not likely to be identified and arrested and that the complainant was not likely to cooperate even if a suspect was identified. Unfounding was used as a way to clear—or dispose of—these problematic cases.

Findings: The Decision to Unfound

The second objective of this study was to identify the factors detectives use when deciding to unfound a case. To achieve this objective, we use the quantitative data extracted from the case files to estimate a binary logistic regression model predicting whether the case would be unfounded. We supplement this with qualitative data from the detective interviews.

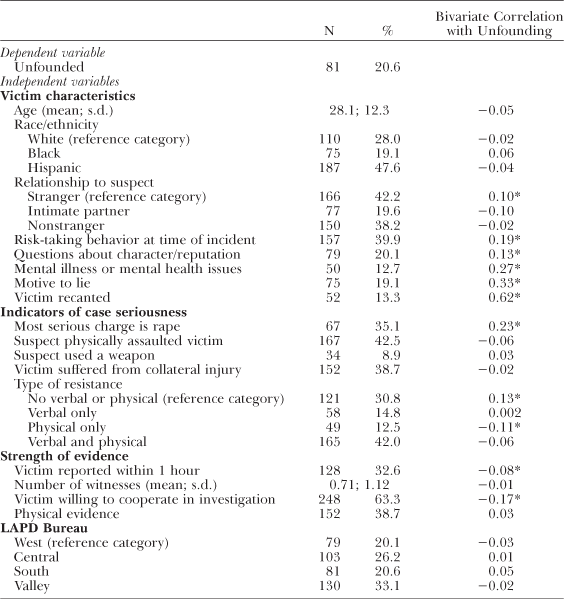

The dependent and independent variables used in the logistic regression analysis, along with their frequencies, are presented in Table 3. We also present the correlation coefficients between the dependent variable and each of the independent variables. The dependent variable is a dichotomous measure of unfounding that is coded 1 if the LAPD unfounded the charges and 0 if the investigation was continuing, the case was cleared by exceptional means, or the case was cleared by arrest. Of the 393 sexual assault cases in our stratified sample that had complete data on all variables included in the model, 81 were cases that were unfounded.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics: Variables Included in Unfounding Analysis

* p ≤ .05.

Our model controls for a wide array of independent variables that prior research has identified as relevant to case processing decisions in sexual assault cases. Although we do not directly test either Reference BlackBlack's (1989) sociological theory of law or the focal concerns perspective (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998), our model includes variables that each theory identifies as important to case outcomes. The victim characteristics include the victim's age as a continuous variable and the victim's race/ethnicity, measured by four dummy variables (white, black, Hispanic, other), with white victims as the reference category. The relationship between the victim and the suspect is measured by three dummy variables (intimate partner, nonstranger, and stranger); cases involving victims and suspects who were strangers are the reference category. To capture whether the victim engaged in any risk-taking behavior at the time of the incident, we created a variable that was coded 1 if the case file indicated that at the time of the incident the victim either was walking alone late at night, accepted a ride from a stranger, voluntarily went to the suspect's house, invited the suspect to her residence, was in a bar alone, was in an area where illegal drugs were sold, was drinking alcohol, was drunk, was using illegal drugs, or had passed out after drinking alcohol and/or using illegal drugs. We also created a variable that indicated if there were any questions about the character or reputation of the victim; this variable was coded 1 if there was information in the case file indicating that the victim had a pattern of alcohol abuse, had a pattern of drug abuse, had a disreputable job (e.g., stripper, exotic dancer), was a prostitute, or had a criminal record. We also control for whether there was information in the case file to indicate that the victim had a mental illness or mental health issues (yes = 1; no = 0)Footnote 7 or to indicate that the victim had a motive to lie about being sexually assaulted (yes = 1; no = 0).Footnote 8 In addition, we included a dichotomous variable indicating whether the victim recanted her testimony (coded 1) or not (coded 0).

Our models also include a number of indicators of the seriousness of the sexual assault, which both of our theoretical perspectives identify as important correlates of decisionmaking. We control for whether the most serious charge was rape (which for these analyses includes oral copulation, sodomy, and penetration with an object) rather than attempted rape, as well as for whether the suspect used some type of weapon during the assault (yes = 1; no = 0), and physically as well as sexually assaulted the victim (yes = 1; no = 0). We also include a variable that measures whether the victim suffered from some type of collateral injury (e.g., bruises, cuts, choke marks) during the assault (yes = 1; no = 0); this information was obtained from the forensic medical report of the sexual assault examination (if there was an examination), from the responding officer's description of the victim's physical condition, and/or from victim's statements in the case file. Finally, we control for whether the victim verbally or physically resisted the suspect using a series of dummy variables (no verbal or physical resistance; verbal resistance only; physical resistance only; both verbal and physical resistance); no verbal or physical resistance is the reference category.Footnote 9

An important strength of our approach is that we were able to control for several variables measuring the evidence in the case. The first is whether the victim made a prompt report (yes = 1; no = 0), which we define as a report within 1 hour of the incident. We also include controls for the number of witnesses to the alleged assault and for a dichotomous indicator of whether the victim was willing to cooperate after the investigation of the case began (yes = 1; no = 0).Footnote 10 Our final evidentiary factor is a composite measure that is coded 1 if any of the following types of evidence were collected from the victim or from the scene of the incident: fingerprints, blood, hair, skin samples, clothing, bedding, or semen. To control for differences across LAPD bureaus, we include a set of dummy variables measuring the bureau to which the case was reported (Central, South, Valley, West); West Bureau is the reference category.

Results from the logistic regression can be found in Table 4. Not surprisingly, the strongest predictor of unfounding was whether the victim recanted the allegations. Of the 55 cases in which the victim recanted, all but seven were unfounded, and about half of the unfounded cases were cases in which the victim recanted. Several other victim characteristics also predicted the likelihood of unfounding, even taking into account whether the victim recanted the allegations. The report was more likely to be unfounded if the victim alleged that she was assaulted by a stranger than if she reported that she was assaulted by an intimate partner. This is not surprising, given that the detectives interviewed for this study indicated that complainants who file false reports are more likely to report being assaulted by strangers. Also not surprising is that fact that unfounding was nearly 10 times more likely if the victim had a mental illness or mental health issues that called her credibility into question. Finally, the LAPD was three times more likely to unfound the charges if there was information in the case file that raised questions about the victim's character or reputation.

Table 4. Logistic Regression Predicting Unfounding

* p ≤ 0.05.

The only other variables that affected the likelihood of unfounding were whether the victim suffered from some type of collateral injury and whether there was any physical evidence collected during the investigation. Unfounding was less likely if the victim was injured and if there was physical evidence. Both injury to the victim and physical evidence serve to corroborate the victim's allegations and therefore make it less likely that the detective investigating the case will believe that the victim fabricated the incident.

The results of the quantitative analysis are confirmed by the comments made by detectives when we asked them about the criteria they use when unfounding a sexual assault report. Consistent with our finding that a victim's recant is neither necessary nor sufficient to unfound a case, a majority of the officers we interviewed reported that they were skeptical of complainants who recanted, noting that recanting “is often based on fear” of the suspect or his family and friends. Typical of these comments are the following:

Either it did not happen in the City of Los Angeles or the victim recants the allegation and you actually believe her. I do believe that there are recantations that are lies. For me, it would take the victim clearly indicating that she lied, providing a rational motivation for lying, and we believe her when she says it didn't happened. Recanting does not necessarily mean that we will unfound the case. If we continue to believe that a crime occurred, the case can be cleared as “IC” [investigation continuing].

Many victims recant because … they are tired of dealing with it; they want to go back to normal and they feel responsible for the stress that has emerged. A victim recant can be used but it should be corroborated and followed up by the detective … to make sure that the recantation is valid.

When asked how they would clear a case in which the victim recanted but the evidence and case factors suggested that the recantation was motivated by threats or intimidation, most of the officers stated that they would present the case to the district attorney for a pre-arrest filing decision. Almost without exception, these respondents noted that the district attorney would reject the case. As one officer put it, “I would not unfound if the victim recanted and the evidence suggested that the crime did occur. But the DA would reject it, absolutely.” Another detective emphasized that “I believe all of my victims until I can prove that they are not telling the truth. If the victim says that it did not happen [and I don't believe her], I still present it to the DA and let the DA decide. They will reject it, of course.” A third officer stated:

I will put it in the report that the victim is being uncooperative and that it appears that she is being threatened or pressured. Talk to her and provide her with referrals to agencies that can help her. But the DA is unlikely to file—you cannot force someone to testify in court and therefore the DA has nothing.

As these comments make clear, when confronted with a complainant who says that the crime did not occur but evidence that suggests it did, LAPD detectives typically—and appropriately—do not unfound the case. Rather, they present the case to the Los Angeles County District Attorney, who rejects it based on the fact that the complainant refuses to cooperate in the investigation and prosecution of the suspect. Our review of these types of cases revealed that the case is then cleared by exceptional means—that is, the officer determines that there is “something beyond the control of law enforcement” (i.e., an uncooperative victim) that prevents them from clearing the case by arrest.

Our interviews with the LAPD detectives also revealed that some officers did not have a clear understanding regarding when cases could be unfounded and the role of victim recantation in unfounding cases. Whereas some detectives stated that victim recantation was neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for unfounding, many others said that they believed a report could be unfounded only if the complainant recanted her testimony and a few stated they would always unfound the report if the victim recanted her testimony. For example, one officer stated that “the only way we can unfound is if the victim tells us it did not happen—there is no other way.” Other detectives stressed that they would only unfound if the complainant recanted or if her story was utterly impossible. As one officer put it:

In order to unfound you have to prove that it did not happen and in order to do that you have to have a victim who recants her story. If it is something that realistically is impossible—she says, “someone flew me to the moon and raped me”—and she continues to maintain that it happened, you can unfound. But you must do a thorough investigation before you can do that.

Another officer stated categorically that “when the victim says I made a false report, it gets unfounded.”

These views regarding the importance of recantation are also reflected in officers' statements about the techniques they use to “get the victim to recant” or to “break her down and admit to what she was really doing.” According to one detective, “we present the conflicting evidence to the victim and try to get the victim to admit that it did not occur.” Another officer recounted a case in which “we really beat the victim up emotionally because we did not believe her story,” and a third stated that the goal with teenagers was to “get them to admit it didn't happen and have them write it down; get them caught in discrepancies and have them tell the story left, right, and center.” These comments suggest that at least some LAPD sex detectives believe that recanting is an important, if not a necessary, element of unfounding; they also believe that it is appropriate to use techniques designed to encourage complainants to recant.

Discussion

The issue of false allegations of rape continues to spark controversy and invite debate. Research focusing on the prevalence of false reports has elicited remarkably dissimilar estimates, with some researchers concluding that false reports are very common and others asserting that they are quite rare. In fact, as Reference SaundersSaunders (2012: 1169) recently noted, “the only thing we know with any certainty about the prevalence of false allegations of rape is that we do not know how prevalent they are.” In a similar vein, Reference RumneyRumney (2006: 158) concluded that, “those writing about the issue of rape have dealt poorly with the issue of false allegations. Given the legal and societal prominence of this subject, it is a failure that should be addressed.”

The purpose of this study was to provide a comprehensive analysis of cases unfounded by the LAPD and, in so doing, to address the prevalence of false reports and, perhaps more importantly, to identify the criteria that law enforcement officials use when determining whether an allegation of rape is a false allegation. A key finding is that, at least in this jurisdiction, false reports of rape are not common. Using weighted data that took into account the fact that our sample was stratified by LAPD division and, within each division, by the type of case closure, we calculated that the overall rate of false reports for the LAPD in 2008 was 4.5 percent, with about half of these cases involving a complainant who recanted. Although this is consistent with estimates of the prevalence of false reports found in recent studies using appropriate methodologies, it is important to point out that our estimate is based on only the unfounded cases we examined. We believe that this rate may underestimate the prevalence of false reports among all cases reported to the LAPD in 2008. This is because our interviews with LAPD detectives revealed that some of them were reluctant to categorize a case as “unfounded,” even if they believed that it was false or baseless; these detectives reported that they would clear the case by exceptional meansFootnote 11 or keep the case open. In addition, we have no way of knowing if there were false allegations that were not recognized as such and that were cleared by arrest or exceptional means. Considered together, these data limitations suggest that the rate of false reports among rapes reported to the LAPD in 2008 may be somewhat higher than 4.5 percent.

Our evaluation of cases that were unfounded by the LAPD revealed that about three-fourths of these cases involved false or baseless allegations; the remaining cases were either clearly not false reports or were ambiguous cases that should have been investigated further before being cleared. Most of the false reports involved allegations of aggravated rape and in about half of the cases the victim underwent a forensic medical exam and eventually recanted the allegations. These results suggest that the LAPD is appropriately clearing cases as unfounded most, but not all, of the time. Generally, the investigating officers are following UCR guidelines and are unfounding cases only after an investigation leads them to conclude that the allegations are false or baseless; they typically do not use the unfounding decision to clear—or dispose of—problematic cases. Nonetheless, there were 10 unfounded cases with compelling evidence that a crime did occur—physical evidence from the forensic medical exam or witness statements that corroborated the complainant's allegations, injuries to the complainant that were consistent with her account of the assault, or evidence recovered from the scene of the crime. In most of these cases, a number of which involved complainants and suspects who were intimate partners or acquaintances, the complainant recanted but it was clear that her recantation was motivated by fear of the suspect, pressure from the suspect or his family and friends, or a lack of interest in pursuing the case. It appears that the victim's recantation and/or lack of interest in prosecuting the suspect led the investigating officer to conclude that the allegations, while not false, were not provable and that the case therefore should be unfounded. Coupled with the fact that there were an additional eight cases that we believed should have been investigated further, this suggests a need for additional training on the decision rules for unfounding sexual assaults.Footnote 12

Also of interest is the fact that more than three quarters of the unfounded reports classified as false allegations were reports of aggravated rape—the complainant reported that she was forcibly raped and indicated that the rape was perpetrated by a stranger, multiple assailants, or a suspect wielding a weapon, or that she suffered from collateral injuries. Many of the complainants, especially young teenagers, reported that they were abducted by a man (or men) in a vehicle (often a white van), taken to an unknown location, threatened with physical harm, and sexually assaulted. Most of the complainants who alleged that they were attacked by a stranger provided very vague descriptions of the suspect, stated that they resisted the suspect physically (e.g., by kicking him in the groin or biting him on the face), and that they somehow managed to escape. The fact that many of the allegations deemed to be false conform so closely to the stereotypical view of forcible rape/real rape (Reference EstrichEstrich 1987; Reference Kalvin and ZeiselKalvin & Zeisel 1966) suggests that complainants believe that their stories will be viewed as more credible if they do not deviate too sharply from society's view of the dynamics of a “real rape.”

Our analysis of the factors that predicted whether a case would be unfounded was guided by a theoretical perspective that incorporated elements from focal concerns theory (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998) and Reference BlackBlack's (1980) sociological theory of law. Both theories predict that case outcomes will be affected by the seriousness of the crime, the blameworthiness and dangerousness of the offender, the credibility of the victim and the suspect, and the character of the victim. Black's theory also posits that outcomes will differ depending upon the status of the victim and the relational distance between the victim and the suspect. Our analysis of the decision to unfound the complaint revealed that whether the victim recants is one of the strongest predictors of unfounding, but other factors such as the victim's relationship with the suspect, whether there were questions about the victim's character or reputation, whether the victim had a mental illness, physical evidence that a crime occurred, and whether the victim suffered from some type of collateral injury also affected unfounding (even after taking recanting into account). These results are generally—but not entirely—consistent with both Black's sociological theory of law and with our assertions regarding the focal concerns that guide police decisionmaking in sexual assault cases. Although Black's theory would not have predicted that cases in which the complainant and suspect were strangers would have a higher likelihood of unfounding, we believe that this finding can be attributed to the fact that complainants who file false reports may believe that their allegations will be viewed as more credible if they conform to stereotypes of “real rape” and/or they believe that it will be more difficult for the police to confirm that their story is a fabrication if the alleged suspect is a stranger rather than an acquaintance. More consistent with both the sociological theory of law and the focal concerns perspective is that indicators of crime seriousness affected the likelihood of unfounding, as did factors that raised questions about the victim's credibility. These findings suggest that police officers' “downstream orientation” (Reference FrohmannFrohmann 1997) to prosecutors leads to a focus on convictability that rests squarely on assessments of the credibility of the victim and the degree to which her allegations conform to or deviate from their “repertoire of knowledge” (Reference FrohmannFrohmann 1991) regarding sexual assault and the behavior of sexual assault victims. Thus, unfounding will be more likely if the victim recants her allegations, has a mental health issue or a motive to lie, or if there are questions raised about her character or reputation. On the other hand, we did not find any evidence that unfounding decisions were affected by the victim's race or ethnicity, as the sociological theory of law would predict, or by the suspect's dangerousness and threat (as measured by use of a weapon and physically assaulting the victim), which is a key component of focal concerns theory. At least in the context of unfounding, these factors appear to be overshadowed by detectives' concerns about the credibility of the victim.

These results were also supported by statements made by detectives during interviews. We found that recanting was an important factor for detectives when deciding to unfound a case, but for most of them the evidence also had to suggest there was no crime. As documented earlier, we also found, however, that detectives who were skeptical of victims' allegations would aggressively question them in an attempt to get them to admit that the allegations were false. As one detective put it, “You can push some victims hard enough that they will recant because they don't want to deal with a difficult investigating officer (IO). [Some IO's] will challenge the victim, confront the victim until she decides that she does not want to have anything more to do with the police.” Future research should examine in more detail the complainant's decision to recant and the role that police questioning may play in this decision. As Reference Patterson and CampbellPatterson and Campbell's (2010; see also Reference DePrince and BelliDePrince et al. 2012) work has shown, victims who were in fact raped may withdraw their participation if they believe that the police blame them for their assaults and question their credibility.

Our study, which is based on data from one of the largest police departments in the United States and is the first to apply the focal concerns perspective (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998) to police decisionmaking and Reference BlackBlack's (1989) sociological theory of law to decisions regarding unfounding, improves on prior research on false reports of rape in a number of important ways. We used a definition of a false rape allegation that is consistent with FBI guidelines for clearing cases; we differentiated between false allegations and baseless reports; and we did not assume that recantation was a necessary or a sufficient condition for concluding that a report was false. We also did not assume that all of the reports unfounded by the LAPD were false or baseless; rather, we reviewed the detailed case file for each of the unfounded cases and, based on the information in the file, determined whether the report was in fact a false allegation. We also supplemented the data from case files with information gleaned from in-depth interviews with sex crime detectives and used both Reference BlackBlack's (1989) sociological theory of law and a revised version of the focal concerns perspective to guide our work on unfounding. Our study is thus more comprehensive and theoretically informed than prior research, and we believe that our findings shed important light on the prevalence of false allegations of sexual assault and the criteria that detectives use in deciding whether a report is false.

We also believe that the findings of our study are more generalizable than those produced by prior research. The two most methodically sophisticated studies of false allegations were conducted using data from England and Wales (Reference Kelly, Lovett and ReganKelly, Lovett, & Regan 2005) and from a university in the Northeastern United States (Reference Lisak, Gardinier, Nicksa and CoteLisak et al. 2010), and it is questionable whether their results are applicable to large police departments in the United States, such as the LAPD. However, given the discretion inherent in the decision to unfound the charges, our findings regarding the ways in which the social structure of the case and police officers' focal concerns affect this decision are not necessarily generalizable to all law enforcement agencies. Although we believe that case convictability and victim credibility will be important focal concerns for all agencies, the ways in which these factors come into play may depend upon the prevalence of sexual assault cases, agency-specific policy statements and training regarding unfounding, and the relationship between the law enforcement agency and the prosecutor's office.

These improvements notwithstanding, our study is not without limitations. Although we were provided with a redacted copy of each case file, we cannot know with any degree of certainty whether the information recorded in the case file was an accurate and unbiased report of what happened and what complainants, witnesses, and suspects said about the alleged incident. In addition, as noted above, although we had the complete case files for each of the 401 cases in our sample, in this study we examined only cases that were unfounded; we did not examine the cases that were cleared by arrest or exceptional means and that also may have involved false allegations. This suggests that our estimate of the prevalence of false allegations of rape may underestimate the actual rate. Finally, we were unable to fully test Black's assertions regarding the relational distance between the victim and the suspect, as we did not have data on their social status and there were too few cases to test for differences for intra-racial versus interracial incident. Clearly, this should be an avenue for future research.

Conclusion

It is clear from this study that some girls and women do lie about being sexually assaulted. More than two-thirds of the cases that were unfounded by the LAPD in 2008 were false allegations in which complainants deliberately lied about being raped. This is clearly a cause for concern. False allegations of rape feed societal perceptions that many rape reports are fabricated and lead to cynicism and frustration among detectives tasked with investigating sexual assaults. They also undermine the credibility of genuine victims and divert scarce resources from the investigation of the crimes committed against them. As Reference Lonsway, Archambault and LisakLonsway et al. (2009: 1) recently concluded, “The issue of false reporting may be one of the most important barriers to successfully investigating and prosecuting sexual assault, especially with cases involving non-strangers.”

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Los Angeles Police Department, which provided the redacted case files used for this study. This project was supported by Award No. 2009-WG-BX-009 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.