What is the future for therapeutics in forensic psychiatry? Predictions are notoriously unreliable and this paper cannot consider all the relevant matters; nevertheless, the few points covered here do raise questions about future directions for the treatment and management of mentally disordered offenders.

PENROSE'S LAW

In Reference Penrose1939 Lionel Penrose, a mental handicap psychiatrist, a professor of eugenics and a psychoanalyst, wrote a paper entitled ‘Mental disease and crime: outline of a comparative study of European statistics’. This paper was a plea for more mental hospital beds in order to reduce both the prison population and the level of serious crime in European countries. British forensic psychiatrists from time to time vaguely wave their hands and talk of Penrose's law, by which they mean an apparently inverse relationship between the number of mental hospital beds and the number of prisoners in any given society, the implication here being that patients turned out of mental hospitals end up in prison.

Penrose's thesis was actually more complicated. He calculated the number of people in mental ‘institutions’, as he called them, in 14 European countries and correlated the rates of mental institutionalisation with the number of prisoners per 1000 population in the same country and with the number of convictions of serious offences in those countries. He found his highest correlation to be an inverse one between the number of mental hospital inmates and the number of deaths attributed to murder. There was also a negative correlation between the number of mental hospital inmates and the number of prisoners, and between the number of mental hospital inmates and the number of live births per 1000 population. He concluded that “attention to mental health may help to prevent the occurrence of serious crimes, particularly deliberate homicide”.

All this seems remarkably familiar and indeed modern. Great stuff for journalists. The difficulties with it are: mental ‘institutions’ in 1939 were heavily weighted with hospitals that accommodated people with mental deficiency; there is no evidence that as mental hospital populations fall and as prison populations rise, the same individuals move between those two kinds of institutions (Reference Steadman, Coccozza and MelickSteadman et al, 1978); and we know that in spite of popular belief a rising murder rate in the UK, for example, cannot be attributed to deinstitutionalisation of people with mental disorders (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1999). Further, it seems very strange to expect ‘deliberate’ homicide to increase if the psychiatric patient population free in the community rises. Even the ‘mad axe-man theorists’ would not expect that.

Paradoxically, however, the idea of Penrose's law has remained alive because one of his findings - an inverse relationship between mental hospital patient numbers and prisoner numbers - has proved remarkably robust. A much better paper on this point was published more recently from Australia (Reference Biles and MulliganBiles & Mulligan, 1973). Biles & Mulligan studied the relationship between the daily average number of people in prison in the six states of Australia, the number on probation, the number in mental hospitals, the police/public ratio and crime rates. Only two correlations between these two statistics proved to be significant. One showed that the amount of reported crime was related to the number of police. The other showed an inverse relationship between mental hospital accommodation and imprisonment rates. The amount of crime in a community did not, as Penrose had predicted, correlate with the number of mental hospital beds. Biles & Mulligan concluded that although official Australian statistics supported Penrose's contention that where the mental hospital population is high the prison population will be low, and vice versa, they did not suggest a comparable inverse relationship between the amount of crime and the extent of mental health services. Indeed, in their view: “hospitalisation of more of the mentally defective or mentally ill is unlikely to lead to a commensurate drop in the officially recorded crime rate. Rather, the data are consistent with the view, also canvassed by Penrose, that the relative use of mental hospitals or prisons for the segregation of deviants reflects different styles of administration”.

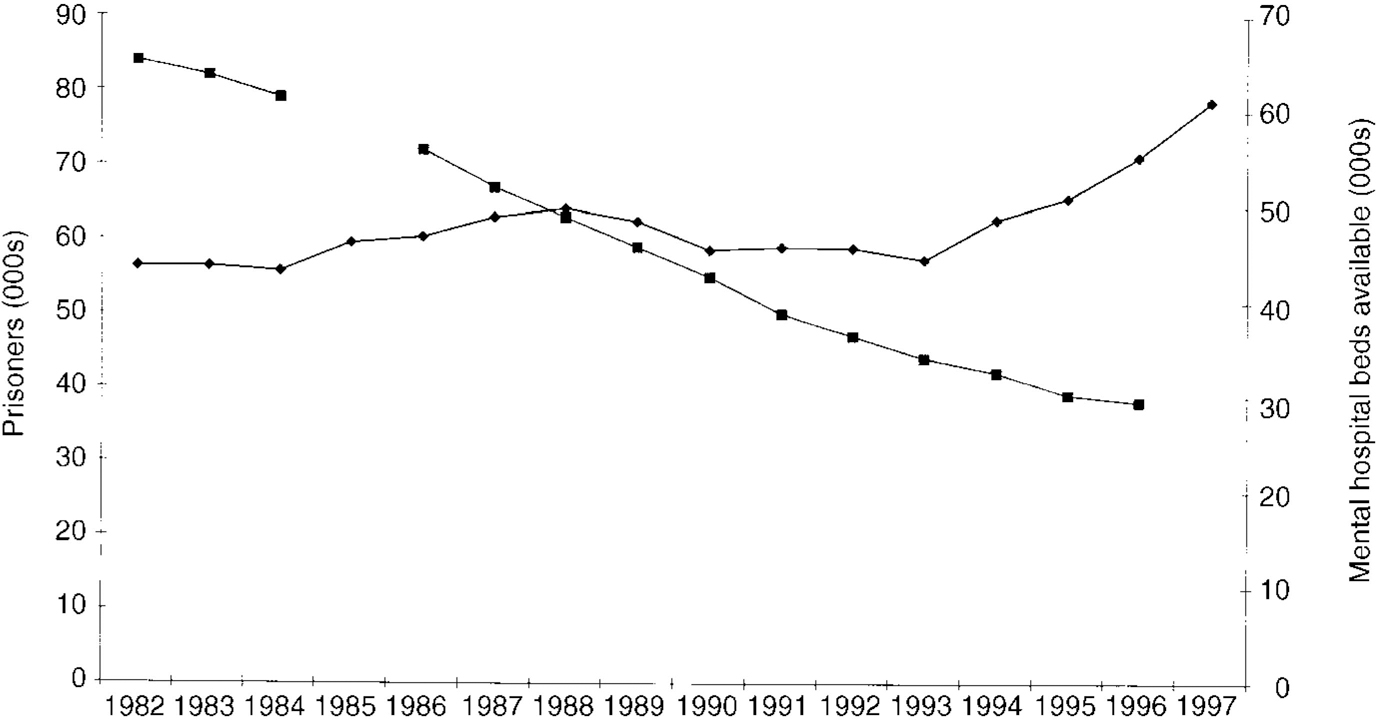

A simple examination of the figures for England and Wales shows that the numbers of mental hospital beds and the numbers of prisoners have been inversely related in recent years. Figure 1 shows the rise in the number of prisoners between 1982 and 1997 and the fall in the number of mental hospital beds available over the same period. (The data for this figure were gleaned from various Health & Personal Social Services Statistics published by the Department of Health (England) and Home Office Statistical Bulletins, all available from HM Government Statistical Service.)

Fig. 1 Graph illustrating the increase in number of prisoners (♦—♦) and decrease in number of mental hospital beds (▪—▪) in England and Wales, 1982-1997.

PRISONS AS HOSPITALS

American authors are in no doubt that their jails are taking over from mental hospitals. For example, Torrey (Reference Torrey1995) conducted a survey of American jails and concluded “quietly but steadily, jails and prisons are replacing public mental hospitals as the primary purveyors of public psychiatric services for individuals with serious mental illnesses in the United States”. He reported that in the San Diego county jail 14% of male and 25% of female inmates were on psychiatric medication. He also said that the majority of seriously mentally ill individuals who end up in jail have been charged with relatively minor offences. In a 1992 survey of jail officials, the most common reasons for jailing seriously mentally ill individuals were said to be assault, theft of property or services, disorderly conduct, alcohol or drug-related charges and trespassing. Torrey pointed out that “the most sobering side of gaol diversion, however, is the assumption that there are public psychiatric services to which the mentally ill individual can be diverted. This, as many law enforcement officials have learnt, frequently is not the case”.

Torrey quoted a 1994 press release from the US Department of Justice. It said that American jails held 454 620 inmates in 1993, state and federal prisons held another 909 185 inmates and yet another 671 470 released inmates were on parole, making a grand total of 2 035 275 individuals in gaol, prison or on parole. If, he speculated, 8% of this population were seriously mentally ill, that is a total of 162 822 people, or twice the number of seriously mentally ill individuals in state mental hospitals on any given day. More recent figures indicate that by mid-1998 the jail population had risen to 592 461 and the federal prison population to 1 210 034 (Reference GilliardGilliard, 1999), that is a rate of incarceration of 668 inmates per 100 000 US residents or 1 in every 150 US residents were incarcerated. The female prisoner population grew at a faster rate (5.6% per annum) than the male population (4.7% per annum).

Teplin has studied the epidemiology of mental disorder in the largest American jail, Cook County Jail in Chicago. She found that 9% of male urban gaol detainees had a severe disorder (schizophrenia or major affective disorder) at some time during their lifetime, 6% had a current episode and that these rates were two to three times higher than the general population rates (Reference TeplinTeplin, 1990). A further study of women prisoners in Chicago was even more startling. Over 80% of the female sample met the criteria for one or more lifetime DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) psychiatric disorders; 70% were symptomatic, within six months of the interviews. Substance abuse or dependence was extremely prevalent, affecting 70% of the sample overall and 60% within six months of the interview. Drug abuse was predominantly heroin and cocaine abuse. Teplin et al (Reference Teplin, Abram and McClelland1996) went on to study the provision of services for these women and found that less than one-quarter of female jail detainees, who had severe mental disorders and needed services, received them while they were in Cook County Jail.

Is the British picture different? Our group at the Maudsley in London has undertaken three national surveys of prisoners in England & Wales. The first was by questionnaire, with 10% of the sample also being interviewed by experienced psychiatrists (Reference Gunn, Robertson and DellGunn et al, 1978). We found that approximately one-third of the prison population, both remandees and sentenced men, could be regarded as a psychiatric case. About 1% of them suffered from schizophrenia, 1% from affective psychosis, 22% from personality disorder and 16% from substance abuse, mainly alcoholism. In 1990, we conducted an interview survey of a random sample of sentenced prisoners throughout England and Wales (Reference Gunn, Maden and SwintonGunn et al, 1991). This time we found that among adult males 2.4% suffered from psychosis, 8.8% from personality disorder and 22.7% from substance abuse, with 44.7% of the sentenced male population receiving a diagnosis of some sort. Women sentenced prisoners had higher figures for everything but psychosis, and 65.6% of them attracted a diagnosis. We carried out a study of remanded prisoners in 1995 and this time we found that 6% of adult males suffered from a psychosis, 11% a personality disorder, 39% were substance abusers and 66% attracted a diagnosis (Reference Maden, Taylor and BrookeMaden et al, 1995). Again the figures for women were higher, with 4% attracting a diagnosis of psychosis, 16% of personality disorder, 42% were substance abusers and 77% attracted a diagnosis of some sort (Table 1).

Table 1 Institute of Psychiatry Prison Surveys (1990 and 1995) in England and Wales

| Adult males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remanded | Sentenced | Remanded | Sentenced | |

| Psychoses | 6% | 2% | 4% | 1% |

| Neuroses | 28% | 6% | 47% | 15% |

| Personality disorder | 11% | 9% | 16% | 16% |

| Sexual deviation | 3% | 3% | 0 | 0 |

| Substance abuse | 39% | 23% | 42% | 31% |

| Organic | NK | 1% | NK | 3% |

| Any diagnosis | 66% | 45% | 77% | 66% |

| No diagnosis | 34% | 55% | 23% | 34% |

| Total | 544 | 1365 | 245 | 273 |

A more recent survey carried out by the Office for National Statistics (ONS; Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998) suggested even higher figures (Table 2). This apparently indicates a recent increase in the psychopathology of prisoners. However, the techniques used by the ONS were rather different from those used in our clinical survey by experienced psychiatrists. The ONS used standardised clinical interviews administered by non-psychiatrists. The most glaring discrepancy is shown in terms of the figures reported for personality disorder. It seems unlikely that a standardised clinical interview approach using SCID-II (Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1996), for example, is particularly meaningful in terms of identifying personality problems that require medical attention.

Table 2 Office for National Statistics Prison Survey (1997) in England and Wales

| Males remanded | Males sentenced | Females | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosis | 10% | 7% | 14% |

| Personality disorder | 78% | 64% | 50% |

| Neurosis | 59% | 40% | 63% |

| Alcohol abuse | 58% | 63% | 39% |

| Drug abuse | 73% | 66% | 56% |

In our survey we were as concerned with clinical need as with diagnosis and we assessed treatment needs in terms of those that we would have ideally prescribed if given the opportunity, and we recorded the treatment currently being received among the sentenced population. In summary, we assessed that almost one-quarter of adult males needed treatment in prison but only 7% were getting it, one-fifth of male youths needed treatment but only 4% were getting it and a startling 43% of women needed treatment but only 15% were receiving it. Table 3 shows the position for the sentenced men.

Table 3 Treatment needs of sentenced adult males

| Ideal | Current | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Out-patient | 140 | 10 | 70 | 5 |

| Community therapy | 80 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| National Health Service | 48 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Further assessment | 68 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Prison hospital | 0 | 0 | 24 | 2 |

| Nil | 1029 | 76 | 1271 | 93 |

| Total | 1365 | 100 | 1365 | 100 |

Focusing on drug dependency alone, we have noted that the current British situation is really a lost treatment opportunity (Reference Brooke, Taylor and GunnBrooke et al, 1998). We found that there was considerable under-reporting of drug-taking. Prison methods of managing drug misuse acted as a deterrent to reporting: “if you tell the prison doctor you take drugs, they strip search you, then your cell, and watch your visits”. Further, almost no help is given in a prison other than initial detoxification to tide the prisoner over the initial withdrawal.

Is it universally true that prisons collect an excess of psychopathology? If so, why is this? Even more important: is it universally true that the level of psychopathology prevalent in prisons is receiving an inadequate service? Certainly the surveys quoted above would suggest that this is the case. To reinforce the unmet needs point in the sentenced prisoners survey we found that a large number of prisoners (approximately 1000 for England and Wales) actually required fairly urgent transfer to National Health Service (NHS) psychiatric hospitals, transfers that were not forthcoming and looked likely not to occur (Reference Gunn and MadenGunn & Maden, 1998).

Presumably this is all a reflection of the administrative style of management that Western countries choose for mentally disordered offenders at the present time. In Britain there are opportunities to choose other forms of management, because there are also secure hospitals available, and there is a growing discipline of forensic psychiatry that is beginning to link with community services and in some areas developing dedicated community services. This may be an unusual model by international standards, and it is clear that it is not entirely successful in keeping levels of psychopathology in prisons down to acceptable levels. It is stated government policy in the UK that psychiatric services for offenders should, as far as possible, be provided within the NHS (or at least, that was policy until quite recently, but I will return to that below). Given the high level of psychopathology that is found within British prisons, this is closer to political rhetoric than to effective policy-making.

PRISONS V. HOSPITALS

Does all this matter? Are prisons and hospitals that different anyway? Is the only real difference between prisons and hospitals the fact that hospitals are much better resourced in terms of doctors, nurses, medicines and the general paraphernalia of therapeutics? If prisons were similarly equipped, would they be as good at treatment as hospitals? Probably not. There are fundamental differences between prisons and hospitals. Hospitals are intended to be entirely benign. Although they can become places of detention for some psychiatric patients, such detention is different in degree and intent from detention in prison, and is surrounded by totally different procedures and laws. Prisons are intended to be sinister and punitive. One of their functions is supposed to be deterrence, so that all of us look at the prison wall and shudder and behave ourselves better. Nobody goes to prison voluntarily. Prison sentences are prescribed in terms of penal tariffs and preventive detention. This punitive aspect to imprisonment is a terrible problem for prison staff, whatever the nature of their charges. Civilised behaviour does not emerge from punitiveness and if prisons were really as punitive as public fantasy allows, they would become totally uncivilised, destructive places; destructive to staff as well as to inmates. Just imagine the nightmare of driving from home each morning knowing that the ‘work’ ahead is mainly about being unkind or damaging to people! The reality is that prisons are actually quite good at a number of positive roles, such as education and rehabilitation. The vast majority of prison staff are caring and relate well to their charges.

There is even evidence that prisons can be quite effective at some forms of treatment. Therapeutic communities are unusual forms of treatment and they can occur both in hospitals and in prisons. In England there is a well-known therapeutic community at Grendon prison, which works well and has reasonably good results (e.g. Reference Gunn, Robertson and DellGunn et al, 1978). Grendon is, however, an unusual prison and it is very obviously separated from mainstream imprisonment both ideologically and geographically. So why not turn all prisons into institutions that can deliver effective psychiatric treatment? Well, at one level prisons can never be hospitals because a true hospital does not carry with it any punitive intent or stigmatising intent. If punitiveness or stigmatisation becomes associated with a hospital, then it is an indication of a poor hospital and efforts will be made to eliminate these features. Imprisonment necessarily embodies both. It is this dilemma that has to be confronted by anyone who would argue that prisons are a suitable place to focus psychiatric treatment.

ATTITUDES TO MENTALLY DISORDERED OFFENDERS IN BRITAIN

If, as suggested by Biles & Mulligan, the current emphasis on imprisonment for people with mental disorders is simply a style of administration, the question remains to be answered as to why imprisonment is the preferred style of administration at the present time. Here we enter the realm of pure speculation. I shall examine four possible factors that have to be examined. Space and lack of real information and expertise will prevent their proper exploration.

The first factor is public panic about the dangerousness of people with mental disorders. This is part of the stigma attached to ‘criminal lunatics’, as the pejorative term calls them - it is probably as old as mankind. It may have been exacerbated in recent years by the ubiquity of both print and electronic media, but it is not a very recent phenomenon. Perhaps the growth of asylums in the 19th century gives a close insight into the public fear of madness. The Malleus Maleficarum (Reference Kramer and SprengerKramer & Sprenger, 1486) is a 15th-century textbook of ‘psychiatry’ that told its readers how to identify witches. Basically, a witch was a mentally disordered person who would not respond to drugs. If there was no response to drugs, then the abnormality must be caused by an evil devil. (I wonder whether anybody else sees the modernity of this approach!) The devils were induced by carnal lust, which was apparently more common in women than in men. The devil had to be destroyed and that was usually by fire (pity about the host). There seems to be a basic human fear of ‘irrational’, ‘crazy’, ‘unpredictable’ behaviour that is conceived of as malign and often homicidal. Basic terrors about being struck down by a mad axe-man make good newspaper copy, and every crime reporter is on the lookout for a story about an incomprehensible lunatic who strikes randomly and murderously.

The second factor that may be contributing towards an increase in the use of imprisonment is economics. It may be believed by politicians and civil servants (and they are the ones who finally make the decisions that determine what happens to people) that imprisonment is a cheaper option than other forms of management for mentally disordered offenders. There is not much doubt that prisons are cheaper than hospitals on a simple cost per person per week basis. However, I cannot find an adequate economic study that compares the costs of effective mental health care for offenders largely outside the penal system with management within the prison and probation services. It would be extremely difficult to carry out because it would have to compare effectiveness between the systems and see which system incurs the higher cost of incarcerating for the longer period and the reduced costs of the more effective system in terms of damage to victims and police budgets.

The third factor in the increasing use of imprisonment for mental disorder may be a broad socio-political attitudinal change, which for brevity I will call the death of liberalism. In the 1960s and 1970s politicians were able to campaign successfully with a liberal manifesto. This no longer seems to be the case, and indeed a recent American president, George Bush, said that for him liberal was a dirty word, and a recent British prime minister, John Major, urged the population to care a little less and condemn a little more. Both of these statements are quite remarkable changes from the policies espoused on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1960s and 1970s. In such a climate as exists at present, obtaining sympathy and resources for a mentally disordered person who has committed a crime is extremely difficult, and perhaps courts reflect the mood of the times and offer punitive responses to medical problems. It is more likely that the political climate keeps the resources for mentally disordered offenders at a low level and thus there are few practical or constructive options to apply. Barchas et al (Reference Barchas, Elliott and Berger1985) called inadequate funding for research on mental disorders “the ultimate stigma”.

An important aspect of the death of liberalism is the attitude taken by professionals, particularly psychiatrists, towards offenders with mental disorders. The political agenda for mentally disordered offenders is partly driven by the medical profession. Buchanan & Bhugra (Reference Buchanan and Bhugra1992), in a review, found that psychiatric patients are regarded by students and doctors (all specialities) as “not easy to like” and unsatisfying to treat. It would be interesting to survey medical opinion on mentally disordered offenders. In Britain we have the remarkable phenomenon that large numbers of quite severely disordered people who require considerable therapeutic effort are deemed “ untreatable”. This notion has been fuelled by the Mental Health Act 1983, which has given to the medical profession a convenient device for rejecting difficult, unpopular and antisocial patients. The Act says that if a legal label of ‘psychopathic disorder’ can be attached to a mentally disordered offender, then it is open to a prospective medical therapist to argue that this case is too difficult and ‘untreatable’ and shall thereby be rejected. I do not believe that this was the intention of the draftsmen of the Act; they were more likely concerned about indiscriminate longterm incarceration of individuals picked on by psychiatrists as troublesome, and locked-up without proper therapeutic endeavour. As liberalism has diminished, Parliamentary concerns have changed.

The net result of this device within the British Mental Health Acts has been that quite a large number of psychiatrists have been able to reject quite a large number of difficult long-term patients. When such patients are rejected, they do not disappear; they have to be looked after by other agencies who, at the very least, are no better equipped than the health care agencies to manage the patients. Many of the patients are unpopular because of antisocial behaviour, so it is usually the criminal justice system that has to pick up the psychiatric rejects; such people either go to prison, where they are very difficult to manage in an environment that is not constructed for their needs, or, just as commonly, they are handed to the probation service to manage.

PEOPLE WITH ‘DANGEROUS SEVERE PERSONALITY DISORDER’

It was fairly predictable that irritation about this would lead to considerable annoyance and ultimately frank anger among prison officers, judges and probation officers. Unfortunately, no constructive dialogue has taken place between professionals in the criminal justice system and psychiatrists. The buzz-word ‘multi-disciplinary’ in mental health care omits criminal justice professionals. Mutually agreed policies between health care and criminal justice personnel might have led to some resolution, but instead it has led to a remarkable new policy by the English Home Secretary (Jack Straw), who wants to remove the safeguards so carefully added into the Mental Health Act 1983 by Parliament, and to endorse positively the notion that individuals with what he calls “dangerous severe personality disorder (DSPD)” can be removed from public gaze into preventive detention, whether or not they have committed an offence.

Mr Straw said, in the House of Commons on 15 February 1999:

“Up until now we have dealt with those who are capable of committing acts of a serious sexual or violent nature in one of two ways - by conviction and imprisonment through the criminal courts, or by detention on the recommendation of doctors under powers within the Mental Health Acts. There is, however, a group of dangerous and severely personality disordered individuals from whom the public at present are not properly protected, and who are restrained effectively neither by the criminal law, nor by the provisions of the Mental Health Acts…Because current mental health legislation prevents a detention, even of a person posing the highest possible risk to the public, unless doctors also certify that the condition is treatable, those people remain at large and without the benefit of any attempts at clinical intervention unless and until they can be convicted of a further offence. In a limited number of cases, such people may not have come to the attention of the criminal justice system at all…society cannot rely on a lottery in which, through no fault of the courts, some dangerous, severely personality disordered people are sent for a limited time to prison or to hospital, while others remain in the community, or return to it, with no interventions whatever…the government proposes that there should be new legislative powers for the indeterminate, but reviewable detention of dangerously personality disordered individuals. These powers would apply whether or not someone was before the courts for an offence. However, the new powers would themselves be exercised by the courts, and not by the Executive, and only where it could be established that the individual had a recognised severe personality disorder, and that he or she posed a grave risk to the public…The individuals concerned must have the best possible chance of becoming safe, so as to be returned to the community, whenever that is possible. We, therefore, propose to establish a range of specialist programmes and a new approach to managing the detention of all those detained under the new powers…we are looking for a standard of proof similar to that which applies within the mental health provisions - one that is bespoke for judging these matters, and above all…for establishing whether a serious personality disorder poses a grave risk to the public. The protection of the public must be the paramount consideration when the courts are judging whether to make an order of this kind…Such a sentence would be passed not as punishment in respect of an offence, but properly to protect the public and to deal with the situation that has rightly alarmed Honourable Members on both sides of the House…People should not be written off as untreatable. Somebody may be deemed untreatable by a particular group of psychiatrists, but be susceptible to treatment by clinical psychologists, psychoanalysts or psychotherapists, or just within a therapeutic community. We should not write anybody off.” (Reference StrawStraw, 1999)

This statement was coupled with a declaration of intent to issue a consultation paper. There are one or two points worthy of note. First, the political use of medical terminology. What in this context does this term “ dangerous severe personality disorder” mean? What Mr Straw may well mean is patients who give him the biggest political problems, such as persistent sex offenders (especially paedophiles and rapists) and those who are sadistically violent and homicidal. These groups of patients are better described in simple and criminal terms. Quite a high proportion of the sadistically violent will suffer from psychosis. Many will misuse substances. Psychiatry is confused and illogical in its approach to the concepts embodied under the broad umbrella of personality disorder. Has our philosophical muddle about terminology and the concepts behind the terminology handed politicians new devices for social control?

The second point to note is that Mr Straw's statement puts a very large emphasis on dangerousness and risk without acknowledging the complexities of those concepts (Reference GunnGunn, 1996; Reference BuchananBuchanan, 1999), and he seems to be confronting the current public panic about mentally disordered offenders. Third, in best Parliamentary language he is expressing considerable irritation with psychiatrists who write off patients and call them untreatable; this could even be the main dynamo for the new proposals.

The new facilities that Mr Straw alluded to, but did not expand upon, will presumably be within his own sphere of influence and thus within the prison system. In this statement, therefore, it seems that Mr Straw is tacitly acknowledging that the prison system is, in his opinion, a suitable place for treating some mentally disordered offenders. This looks a bit like a change of government policy that has hitherto regarded the treatment of mentally disordered people as exclusively a health service task. It may actually be a reduction in the rhetoric about not treating offenders in prison and a tacit acceptance of the situation that has probably always existed.

DIFFERENT ETHICS FOR FORENSIC PSYCHIATRISTS

Do these shifts of emphasis within Britain have parallels in other parts of the world? It is difficult for a British observer to answer that question, but I am struck by an entirely different debate that is occurring within the psychiatric profession in North America. Is it possible that this apparently unrelated issue is a reflection of the same trend to criminalise patients?

Appelbaum (Reference Appelbaum1997a ) has told us: “for forensic psychiatrists, the primary value of their word is to advance the interests of justice. The two principles on which that effort rests are truth-telling and respect for persons…Forensic psychiatrists cannot simply rely on general medical ethics, embedded as they are in the doctor-patient relationship - which is absent in the forensic setting”. Also: “Treating clinicians (not just psychotherapists) have primary obligations to advance their patients' interests and avoid causing harm, reflecting the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. In revealing information to treating psychiatrists, patients - except where the physical safety of others is endangered - can be assured that their disclosures will be used by their psychiatrists only to further their interests. Forensic psychiatrists, however, work in an entirely different ethical framework, one built around the legitimate needs of the justice system. Their duties are to seek and reveal the truth, as best they can, whether or not that advances the interests of the evaluee” (Reference AppelbaumAppelbaum, 1997b ).

For my part, I find it very difficult to understand how a doctor can stop being a doctor. Perhaps it will help me to know all this next time I am on an aeroplane and the dreaded call for a doctor goes out. I will be able to say “ today I am not a doctor, I am a forensic psychiatrist” and so I will be able to sit on my hands with a clear conscience! Furthermore, I do not have faith in the ultimate attainment of ‘truth’, especially when the ‘truth’ about a patient is to be determined by a stranger, a non-therapeutic, semi-doctor, rather than a healing doctor who knows the patient well and who has a reasonable chance of providing meaning to seemingly irrational acts. The notion of an elusive ‘truth’ that can somehow be distilled and brought into a courtroom is actually not a notion that is shared by the Anglo-Saxon legal system itself, which is used on both sides of the North Atlantic. Both in Britain and America the adversarial system does not depend upon finding ‘truth’ but upon hearing two sides of an argument and judging between those sides. In my experience, courts are quite capable of understanding that the doctor brings a particular viewpoint to his or her reporting, and will probably bring a medical viewpoint and indeed a pro-patient viewpoint, irrespective of whether he or she is well acquainted with a patient, and irrespective of which lawyer has instructed him to carry out an examination. To be fair, Appelbaum does accept that “the success of any moral theory depends on how well it satisfies its audience”. It will be interesting to see how far the psychiatric profession of the USA embraces Appelbaum's ideas, and furthermore it will be interesting to see whether the American people and its judiciary also welcome these proposed changes.

Are these attitudes a reflection of a professional attitudinal shift away from treatment? Are both the British desire to reject ‘untreatable’ patients and the American desire to eschew the therapeutic role in favour of a quasi-legal role two reflections of a trend in psychiatry that is, at least in part, responsible for the increasing use of prisons as mental hospitals? Research on this topic would be invaluable.

DISCUSSION

Penrose believed that more psychiatric treatment would reduce rates of crime. This seems unlikely, except possibly in a way that he had not considered - by the more effective treatment and prevention of substance misuse; however, the prevention of substance mususe is a task that goes far beyond psychiatry. In one matter Penrose was right. As mental hospitals are closed, so prisons are filled and/or opened. These phenomena may not be connected directly but they may be related to other factors that are also changing, such as political beliefs and medical attitudes. The rejection of patients as ‘untreatable’ and the call for forensic psychiatrists to leave, at least in part, their medical role may reflect changes of medical attitude that are contributing to a rise in the number of patients in prisons.

Those who believe that current trends are inappropriate or wrong need to consider how they can be halted or even reversed. If there is a simple cause and effect relationship between prison populations and hospital populations, then opening more hospital beds ought to do the trick. But, if, as seems more likely, the shifts in attitude are the basic issue, then a much more complex approach would be required. More information is needed about the ways in which doctors acquire attitudes. More dialogue between the various professions involved with mentally disordered offenders seems vital and the use of non-medical professionals to teach undergraduate doctors would make much sense. The professions who need to talk and perhaps undertake collaborative research and teaching are psychiatrists, mental health nurses, psychologists, probation officers, police officers, prison officials and lawyers, especially judges. Her Majesty's Government could help in Britain by encouraging young doctors to take up psychiatry. Pillorying doctors, as is current policy, for example through a statutory public inquiry each time a patient commits homicide, makes good tabloid copy but it does very little for recruitment, and recruitment into the mental health professions is the number one issue in Britain.

Perhaps the basic public fear of people with mental disorders is too basic and too entrenched to be changed, and yet nobody burns witches any more, reason does play a role in public attitudes and political pendulums that swing right can also swing left. The curious date change that has recently occurred is itself laden with anxieties of doom and destruction (millennium bugs are perhaps modern devils), but it also makes us look further ahead than we do usually. Can we expect that in 2099 prison populations will have fallen and a lower proportion of them will be needing psychiatric services in prison itself because forensic psychiatry services will be adequately funded and will have doctors queuing up to join its ranks? To misquote Samuel Johnson, perhaps hope will triumph over experience.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Mental health professionals and authorities should give greater priority to psychiatric services for prisons.

-

▪ Prison authorities need to examine ways of increasing the level of psychological and psychiatric services within their institutions.

-

▪ The psychiatric profession needs to introspect on the reasons for prisons replacing mental hospitals and whether it wishes to develop a branch of practitioners who have a different (non-medical) set of ethics.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The research base in respect of attitudes towards mentally disordered offenders is almost non-existent.

-

▪ Attitudes and politics can change rapidly, and it is possible that this paper could become outdated quite quickly.

-

▪ Transatlantic philosophical and legal comparisons may be misleading.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.