Introduction

Located in the Horn of Africa (Figure 1), Ethiopia is remarkably varied, both environmentally and topographically. It is also ethnically and culturally diverse, and is home to followers of three major world religions: Christianity, Islam and Judaism—as well as adherents of various African Indigenous religions (Quirin Reference Quirin1998; Insoll Reference Insoll2003, Reference Insoll, Walker, Insoll and Fenwick2020; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009). This environmental, topographic, ethnic and cultural diversity has moulded a rich history that has included, for instance, periodic Ethiopian interaction with South Arabia (e.g. in the mid first millennium BC; Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 121–22), and the growth of the Late Classical kingdom of Aksum around the first century AD (e.g. Phillipson Reference Phillipson2012), prior to the medieval period (c. seventh to early eighteenth centuries AD). Ethiopia's medieval archaeology, and to a lesser extent its late Classical archaeology, are much less well known than the prehistory of the country. It is this medieval period that forms the focus of the present article and of the special section that it introduces.

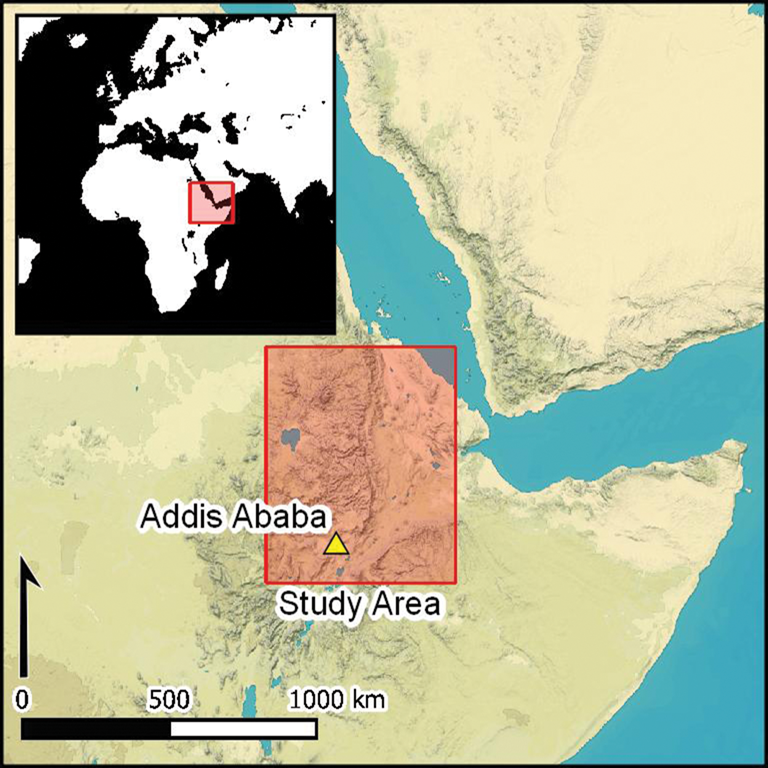

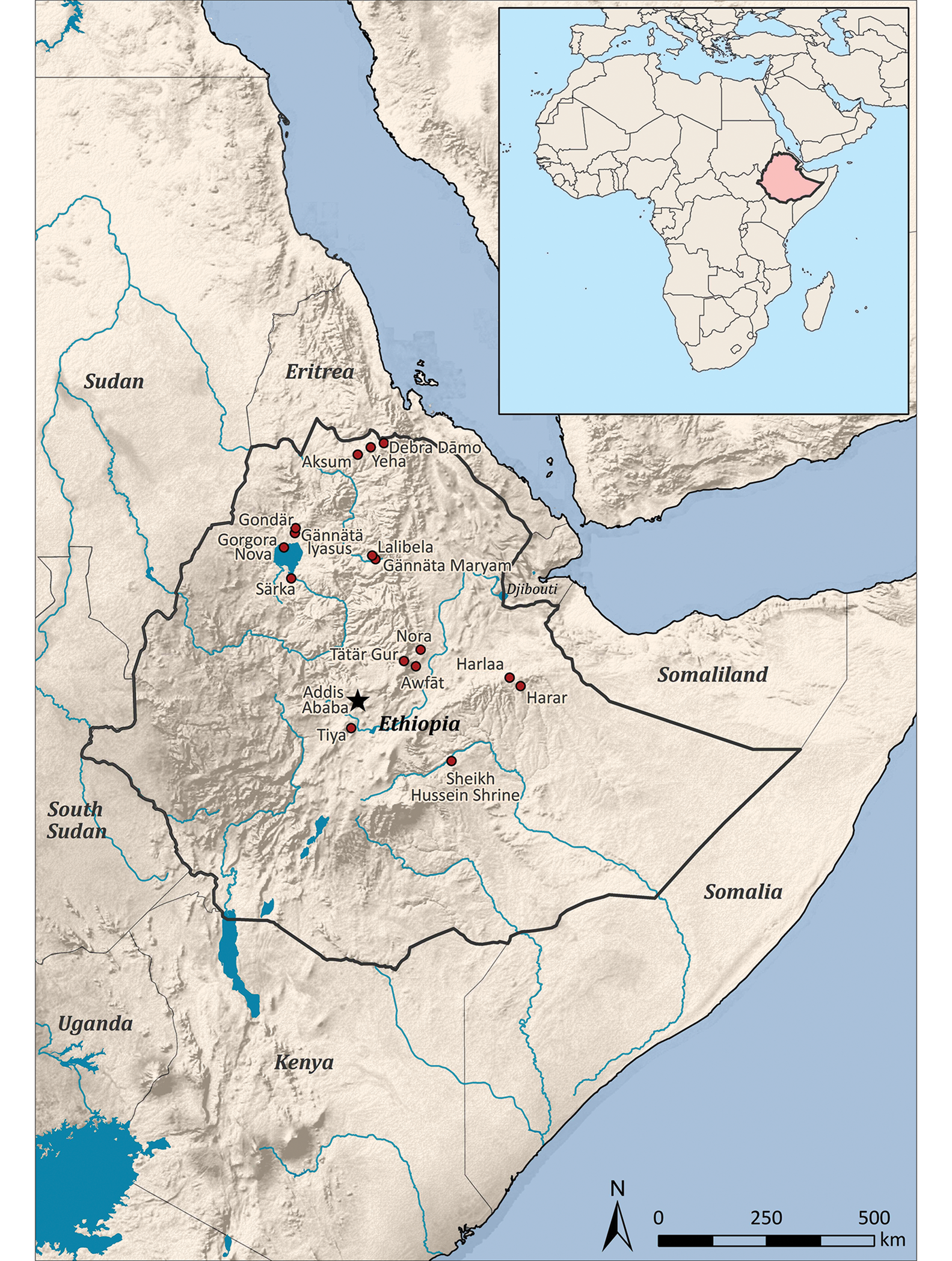

Figure 1. Map of the main sites mentioned in the text (map by N. Khalaf).

From a European perspective, this lack of attention is perhaps partly explained by the view that Ethiopia was isolated—the mountainous land of the legendary Christian king Prester John (Nowell Reference Nowell1953: 437; Axelson Reference Axelson1973: 33–34)—and surrounded by antagonistic Muslim sultanates and barbarous ‘pagans’. Although such views are discredited, archaeology has been somewhat tardy in adding material evidence to the often fragmentary and minimal historical sources, and in linking medieval Ethiopia to the rest of Africa and beyond. Historical biases in research are also evident in the focus on Christian sites and monuments and an absence of investigation of Islamic archaeology (Insoll Reference Insoll2003, Reference Insoll, Walker, Insoll and Fenwick2020). While the reasons for this vary, it partly reflects the imperial Ethiopian historical narrative focused around Orthodox Christianity, partly the view of Islam as foreign and partly because of disinterest (Ahmed Reference Ahmed1992). Similar historical neglect of the archaeology of Jewish and Indigenous religious communities is also apparent, for similar reasons, and because the focus of research was elsewhere: on hominins, prehistory and proto-Aksumite and Aksumite archaeology.

This situation, however, has begun to change, with a range of archaeological research focusing on varied communities—particularly Islamic, as apparent in this special section of articles—and highlighting the complex nature of societies and their relations in medieval Ethiopia. Cosmopolitanism, defined as “a willingness to engage with the other” (Hannerz Reference Hannerz1990: 239), is manifest through material evidence (e.g. trade goods, images, coins, architecture, epigraphy and burial practices) that increasingly demonstrates extensive commercial, religious, social and cultural interaction. These reflect the existence of more fluid, heterogeneous entities—rather than rigorously bounded ones based on a “hard-edged” religious or cultural identity—that “overlap and mingle” (Hannerz Reference Hannerz1990: 239). Thus, to adapt the words of Abbink (Reference Abbink2008: 119), medieval Ethiopia is “best studied and understood as one whole”, rather than as disparate elements. Within this, varied societies were periodically entangled in a range of networks that operated at different scales through long-distance Indian Ocean and Red Sea maritime networks, regional land routes crossing the Horn of Africa and local connections. All of these networks served to move goods, ideas and people, and, in so doing, constructed a cosmopolitan milieu.

This introduction contextualises the following articles in relation to the relevant historical background, with a particular emphasis upon religions, as well as previous archaeological research (and absence thereof). There has been a critical readjustment in archaeological research themes in Ethiopia to those exploring diverse medieval societies. Acknowledging this, and the existence of cosmopolitanism within these societies, however, is not to negate the existence of relations of dominance of one group over another, or of struggle between groups, or periods of isolation. Muslim relations with Orthodox Christian Ethiopian society, for example, were punctuated by periods of conflict during the medieval period. Two were of particular significance: the wars between Emperor Amda Siyon and the Sultanates of eastern Ethiopia in the first half of the fourteenth century (Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972: 132–36), and the jihad of Aḥmad Gragn in the first half of the sixteenth century (Beckingham & Huntingford Reference Beckingham and Huntingford1954: 105; Huntingford Reference Huntingford1989: 120; Kapteijns Reference Kapteijns, Levtzion and Pouwels2000: 229–30; Abbink Reference Abbink2008: 119). Such events could lead to the decline or disappearance of cosmopolitanism—temporarily or more permanently—associated with the construction of more rigid territorial, ethnic and religious boundaries.

It will also be apparent that this special section is largely authored by scholars from outside of Ethiopia. This is unfortunate, but reflects the current situation in Ethiopia, where prehistory and, to a lesser extent, Aksumite archaeology, is more widely studied and supported. With few exceptions (e.g. Worku Reference Worku2018; Woldekiros Reference Woldekiros2019), medieval/historical archaeology has been neglected by Ethiopian scholars. This is, however, beginning to change, with a growth in interest in Islamic archaeology and active capacity-building initiatives embedded within, for example, two of the projects featured in this section (Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021; Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021). Should such a collection as this be published a decade from now, it is likely that this imbalance will rightly have disappeared.

Finally, two terminological clarifications are also required. First, the use of the term ‘medieval’ in the Ethiopian context is justified, for it is a “dead metaphor” and, as such, can be used outside its original European “frame of reference” (de Moraes Farias Reference de Moraes Farias2003: xxiii). Second, Ethiopia is here defined as the land within the borders of the modern nation (Figure 1). These borders, however, did not take shape until the late nineteenth century (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 3), and archaeology indicates that they are arbitrary and that past interaction extended far beyond, across the Horn of Africa, to the Nile Valley and Mediterranean, Red Sea, Western Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf.

Islam and Muslim polities

Links between Ethiopia and Islam were established from the very beginnings of the religion. The first Muslim contacts with Ethiopia were peaceful. According to tradition, the Prophet Muhammad sent small groups of his followers to the court of the Negus—probably the Christian ruler of the Aksumite kingdom—in 615 (all dates are AD, unless otherwise specified), in what is known as the first hijra (migration in Arabic) (Lapidus Reference Lapidus1988: 25; O'Fahey Reference O'Fahey2003: xviii). Whether any of these early Muslims remained in Ethiopia is unknown (see Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021), but by the tenth century Islam had become better established (Ahmed Reference Ahmed1992: 16), and Islamic conversion and Islamisation appear to have been achieved through various agents and mechanisms, including trade, preaching and missionary activity. Muslim polities also developed. The state of Shewa, c. AD 896/897–1285, for example, was centred to the north-east of modern Addis Ababa (Huntingford Reference Huntingford1989: 76). It was absorbed by the Ifāt Sultanate, which gave way in 1420 to the Sultanate of Adal—the powerbase of Ahmad Gragn until his death in 1543 (Kapteijns Reference Kapteijns, Levtzion and Pouwels2000: 228–29).

Archaeology is an important tool for exploring medieval Islamic Ethiopia, as the Arabic historical sources concerned with Ethiopia's interior are limited prior to the seventeenth century (see Ahmed Reference Ahmed1992). Notable texts include those by al-‘Umarī (1301–1349), whose information was gained from second-hand accounts (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, O'Fahey, Wagner and O'Fahey2003: 19–20), rather than by first-hand experience, and the early sixteenth-century Futuh al-Habasha, the chronicle of Aḥmad Gragn's jihad written by Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad (sometimes known as Arab Faqih) (Stenhouse Reference Stenhouse2003). Until recently, the place of Islamic Ethiopia in the medieval Islamic world was largely unknown, beyond the limited textual references to sultanates and kingdoms, such as Ifāt and Adal (e.g. Trimingham Reference Trimingham1952), the recognition of the city of Harar as an important Islamic centre (e.g. Insoll Reference Insoll2003) (Figures 1–2), some Arabic epigraphic studies (e.g. Schneider Reference Schneider1967, Reference Schneider1969, Reference Schneider1970), and acknowledgement that the coastal ports in what are now Eritrea and Somaliland were active participants in Western Indian Ocean and Red Sea trade (e.g. Anfray Reference Anfray1990: 154–59).

Figure 2. Badri Bari, one of the five original gates in the Harar djugel (city wall) (photograph by T. Insoll).

Archaeology has now begun to expand substantially our knowledge of medieval Ethiopia. Although surveys of relevant sites commenced with early twentieth-century pioneers such as Azaïs and Chambard (Reference Azaïs and Chambard1931), excavation was limited (see Insoll Reference Insoll2003: 58–73, Reference Insoll, Walker, Insoll and Fenwick2020). Within the past 20 years, however, the situation has begun to change, beginning with important contributions made by the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies (e.g. Hirsch & Fauvelle-Aymar Reference Hirsch and Fauvelle-Aymar2002; Fauvelle-Aymar et al. Reference Fauvelle-Aymar2006; Fauvelle-Aymar & Hirsch Reference Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2010, Reference Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2011; Fauvelle et al. Reference Fauvelle, Hirsch and Chekroun2017). Investigation of a settlement at Nora in north-eastern Shewa, for example, has revealed a mosque dated to between the mid twelfth and late thirteenth centuries (Fauvelle-Aymar & Hirsch Reference Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2010: 36). At Fäqi Däbbis, also in Shewa, another mosque was dated to between the early fourteenth and mid fifteenth centuries (Poissonnier et al. Reference Poissonnier, Ayenachew, Bernard, Hirsch, Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2011: 135); and a large town and cemetery were recorded at Awfāt, which might be identified with the capital of the Sultanate of Ifāt, occupied by the Walasma‘ Dynasty (1285–1376) (Fauvelle et al. Reference Fauvelle, Hirsch and Chekroun2017: 278–79) (Figure 1). Subsequently, excavations in Harar have revealed a range of settlement and mosque sites dating between the late fifteenth and nineteenth centuries (Insoll Reference Insoll2017; Insoll & Zekaria Reference Insoll and Zekaria2019). Much work, however, remains to be done, and ongoing excavations in Harlaa and Tigray (Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021; Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021) attest the potential of archaeology both for reconstructing medieval Islamic life and the complexity and cosmopolitanism that defined it.

A strong regional Islamic identity developed in Ethiopia, resulting from “original intellectual elaboration” (Fani Reference Fani2016: 114), and akin to the intellectual processes that created a unique Ethiopian Indigenous Orthodox Christian tradition (Mercier Reference Mercier2001; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009). Sufism was popular from the eleventh century (Abbink Reference Abbink2008: 120), and Harar grew as a centre of Islamic scholarship (Santelli Reference Santelli and Jayyusi2008; Insoll & Zekaria Reference Insoll and Zekaria2019). Regional Islamic Indigenous pilgrimages also developed. Focusing on the Sheikh Hussein shrine in Bale (Figure 1), these traditions were possibly founded in the twelfth century (Østebø Reference Østebø2012: 52) and provided a substitute for hajj (Muslim pilgrimage) for those without the means to travel to Mecca (Braukämper Reference Braukämper2004: 144). Furthermore, a manuscript culture persisted for much longer in Islamic Ethiopia than in Islamic Egypt or in the Ethiopian Orthodox church, where, for example, printed books were largely adopted from the mid nineteenth century. Handwritten manuscripts carried prestige and were considered more reliable for teaching and learning (Fani Reference Fani2016: 120), providing continuity of medieval manuscript culture to the present day.

Aspects of Ethiopian Islamic practice were also influenced by Christian traditions, indicating a cosmopolitan ethos. The “deeply monastic” traditions of Ethiopian Christianity (Mulugetta Reference Mulugetta2015: 184) affected the development of Ethiopian Muslim monasticism. Although male-inhabited monastery-like structures, often with a military function (e.g. tekke, ribāt, dergāh and khānqāh), are found elsewhere in the Muslim world (Hillenbrand Reference Hillenbrand1994: 44; Abbink Reference Abbink2008: 122), female monasticism, where women lived in poverty and celibacy in nunneries, was a unique development to eastern Ethiopia (Abbink Reference Abbink2008: 124). Diachronic shifts in Islamic identities can be observed, from the disappearance of Shi'ism (apparently present in medieval Bilet; see Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021), to the contemporaneous decline in Sufism (Østebø Reference Østebø2012), with its supposed connotations of bid‘a (unwarranted innovations in Arabic) under the influence of Salafist Islam (Abbink Reference Abbink2008: 121 & 131), and the move towards a less heterogeneous Islamic practice and belief.

Judaism

The Jewish community further enhanced the complex, cosmopolitan nature of medieval Ethiopian society. Formerly known by the derogatory term ‘Falasha’ (meaning ‘stranger’), the ‘Beta-Israel’ lived within the primarily Christian north-western regions of Wollo, Gondar and Tigray. Their origins have been debated: whether a lost tribe from Israel, migrants from South Arabia who travelled to Aksum in the second/third centuries (Figure 1), or a group who emerged from a Christian schism in the fifteenth century (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1992: 32; Quirin Reference Quirin1998: 198; Salamon Reference Salamon1999: 126). Ethnographically, the Beta-Israel were inter-linked with their Christian neighbours, from whom they were physically and linguistically indistinguishable; material culture production and spatial demarcation served to maintain boundaries.

The Beta-Israel were specialist smiths and weavers (men) and potters (women), producing tools and ceramics vital to Christians, but via crafts neither practised nor esteemed by the latter. Exemplifying what Salamon (Reference Salamon1999: 118) has described as “religious separation” and “connectedness”, Christians could help to bury the Jewish dead, but could not eat meat slaughtered by the Beta-Israel (Mulugetta Reference Mulugetta2015: 184), nor enter their houses. Beta-Israel identity, however, was mutable, as the limited historical sources indicate (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1992; Quirin Reference Quirin1998). The blacksmith/potter/weaver activities, for example, became prominent after Beta-Israel land was appropriated in the fifteenth century. Moreover, from the mid eighteenth century, the Beta-Israel were ascribed a firmer ‘caste’ identity, which was also associated with their being labelled budā, or people with an evil eye (Quirin Reference Quirin1998: 202 & 208–209). An ambiguous relationship was thus maintained, as attested by both ethnography and historical sources (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1992; Quirin Reference Quirin1998; Salamon Reference Salamon1999). Missing, however, is the archaeological dimension, reflecting an absence of research in Ethiopia. Where investigation is occurring—in neighbouring Somaliland for example (Figure 1)—evidence is emerging to suggest that the Jewish presence in the Horn of Africa was more extensive in the medieval period, as attested by two gravestones engraved with the Star of David recorded in the Dhubato area (Mire Reference Mire2020: 28–29). Alternatively, the Star of David might be another instance of the use of the ‘Seal of Solomon’ found in Islamic funerary iconography (see Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021). Christian gravestones, however, were also found nearby (Mire Reference Mire2020), implying that the Horn of Africa was more cosmopolitan than it is today.

Christianity and the Christian kingdoms

Christianity has tended to dominate narratives of medieval Ethiopia because of its long history and links with the Solomonic Dynasty, which reigned from the late thirteenth century, until Haile Selassie was overthrown by the Marxist Derg regime in 1974 (Anfray Reference Anfray1990; Ahmed Reference Ahmed1992; Lepage & Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2005). A further factor was its unique character: Ethiopian Christianity developed its own distinctive, Indigenous traditions that attracted external attention (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 198). Ethiopian contacts with Christianity were early. Tradition records that the conversion of the Aksumite ruler Ezana occurred in the 330s (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 181; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 29). In this first conversion phase, material indicators of Christianity are restricted to stone inscriptions and coinage (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 49, 2012: 99). This soon changed, as, from its urban origins focused on Aksum (Finneran & Tribe Reference Finneran, Tribe and Insoll2004: 65), Christianity was extended into the countryside in the late fifth century by the arrival of monks from the Eastern Mediterranean (Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972: 24). These ‘Nine Saints’ also introduced a monastic tradition into Ethiopian Christianity (Lepage & Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2005: 170), which had a lasting legacy through monasteries such as Debra Dāmo in northern Tigray (Figure 1), founded in the sixth century (Finneran & Tribe Reference Finneran, Tribe and Insoll2004: 65–66). Churches of rectangular basilica form with a central longitudinal space also appeared at this time (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 50 & 204). Yet archaeologically, medieval Christianity in Ethiopia has remained relatively unexplored (Finneran & Tribe Reference Finneran, Tribe and Insoll2004; Finneran Reference Finneran2005, Reference Finneran2007; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009, Reference Phillipson2012), with the research emphasis on art history or architecture, or based on historical sources (e.g. Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972; Mercier Reference Mercier2001; Lepage & Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2005; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009).

In the earliest Christian period, Late Aksumite (sixth century) ceramics indicate the use of various forms of the cross as a decorative symbol (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 31). Aksumite-period churches have also been surveyed, and excavations completed at, for example, Maryam Tsion, Beta Giyorgis, Wuchate Golo, Melazo and Enda Kaleb in Aksum and its surrounding region, as well as at Yeha (see Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 32–44, 2012: 126–32) (Figure 1). Most recently, a fourth-century basilica of tripartite Syriac plan has been excavated at Beta Samati in northern Tigray, with an assemblage of 49 ceramic bucrania and zoomorphic figurines from the church suggesting the mixing of early Christian and Indigenous religious elements (Harrower et al. Reference Harrower2019). Although medieval Ethiopian monasticism has not received the same archaeological attention as contemporaneous traditions in Nubia and Egypt (Finneran Reference Finneran2005: 24, Reference Finneran2012a: 252), limited research suggests connectivity rather than isolation. A fragment of embroidered white cloth bearing a red-silk inscription of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu‘tamid of late ninth-century date, for example, was found in a storeroom in the Debra Dāmo monastery in Tigray. Coins from the surroundings of the monastery also include Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid issues dating from between 78/697 and 331/942 AH/AD (Mordini Reference Mordini1957: 75–77). (AH refers to Anno Hegirae, the Islamic calendar, 1 AH is equivalent to AD 622, and marks the migration, hijrah, of the Prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina.) This material is important in that it suggests economic and other relations between Muslims and Christians, and of cosmopolitanism, rather than “the existence of mutually incompatible blocs of Islam and Christianity” (Insoll Reference Insoll2003: 59).

Archaeology has also had a largely under-utilised role in illuminating the “dark age” (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 207) of Christian Ethiopia, between the ninth and twelfth centuries. This period saw the emergence of the Zagwe Dynasty sometime between the late tenth and mid twelfth centuries, accompanied by the foundation of the capital at Roha (known today as Lalibela, Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 123 & 197) (Figure 1). This was a significant event, as it signalled a shift from Semitic-speaking rulers to—originally at least—Cushitic-speaking rulers (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2012: 227). In the past, research at Lalibela had focused predominantly on the rock-cut, hypogeum churches (Gerster Reference Gerster1970; Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 123; Mercier & Lepage Reference Mercier and Lepage2012) (Figure 3). More recently, archaeological focus has shifted to investigate, for example, the longer term evolution of churches; their stratigraphy and the possible original non-religious functions of some of the structures (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2007, Reference Phillipson2012: 231–35; Finneran Reference Finneran2009: 421–22, Reference Finneran2012a: 266; Fauvelle-Aymar et al. Reference Fauvelle-Aymar, Bruxelles, Mensan, Bosc-Tiessé, Derat and Frisch2010); examining the churches in their landscape setting (Bosc-Tiessé et al. Reference Bosc-Tiessé, Derat, Bruxelles, Fauvelle, Gleize and Mensan2014); placing Lalibela within its wider geographic context (Finneran Reference Finneran2012b); and excavation of a cemetery at Qademt, 500m north of the churches (Gleize et al. Reference Gleize2015). The latter has particularly significant implications for cosmopolitanism, as there were clear changes in burial orientation over three phases between the eleventh and eighteenth centuries, raising the question of whether all the burials were Christian (Gleize et al. Reference Gleize2015: 250). Such changes in orientation, along with the use of stone slabs to cover some of the grave pits, precisely mirror the practices recorded in the Muslim cemetery at Harlaa (see Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021). This perhaps indicates that Muslim-Christian interaction was occurring at Lalibela, although the presence of ceramics in some graves (Derat et al. Reference Derat, Garric, Mensan, Fauvelle, Gleize and Goujon2021)—presumably as grave goods that are not usually found in Islamic contexts (Insoll Reference Insoll1999: 172)—suggests greater complexity.

Figure 3. Church of Beta Amanuel, Lalibela (photograph by M.-L. Derat, Mission Lalibela, 2009).

Finneran (Reference Finneran2007: 225) has suggested that the late tenth- to mid twelfth-century Zagwe Dynasty re-aligned Ethiopian Christian culture away from the Red Sea and Eastern Mediterranean. More recent archaeological research in eastern Ethiopia, however, disputes this, providing evidence that interaction with Muslim neighbours persisted (see Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021; Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021), and an expansion of international contacts may have taken place. This may also be represented by a painting in the eleventh- to twelfth-century church of Debra-Salam in Tigray that depicts a realistic image of an elephant led by two mahouts (see Lepage & Mercier Reference Lepage and Mercier2005: 101)—reflecting knowledge of, or contacts with, South Asia. Yet there were also manifest differences. The types of imported objects, including glass vessels, glazed ceramics, glass and agate beads found in large quantities at Harlaa (see Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021), and more selectively at various funerary monuments associated with Indigenous religions (see below), are absent in centres such as Lalibela and almost absent across the highland Christian sites. With the defeat of the Zagwe in 1270, the Solomonic line was restored, and Semitic-language speakers (Amhara) were restored to power. It is to the latter that most of the historical sources referring to the Zagwe are attributed (Phillipson Reference Phillipson2009: 22, Reference Phillipson2012: 229). This again emphasises the important role of archaeology where historical sources are partial and where those that exist may record events from a particular ethnic or religious perspective.

A notable consequence of this change in power was a shift in settlement: the royal court became mobile, with monasteries providing the fixed socio-economic and religious centres in the landscape (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 237 & 259). The mobile royal camps (katama) evolved standard elements, such as different areas for aides, officials, soldiers, livestock and the royal family, and access to semi-permanent churches, or the use of nearby permanent churches. Palisades could also be used to separate different areas in the camps (Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972: 269–74; Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1979: 3–4; Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 255–57). One such possible camp has been investigated at Gännätä Maryam, which appears to have been located on the plain below the monastery (Finneran & Tribe Reference Finneran, Tribe and Insoll2004: 68) (Figure 1). Another possible royal camp at Manz in north-eastern Shoa, approximately 320km north of Addis Ababa, built during the reign of Ba'eda Māryām (AD 1448–1478), has also been explored (Hirsch & Poissonnier Reference Hirsch and Poissonnier2000). Excavation of an associated church, Mesḥāla Māryām Raphael, attests two main periods involving its initial construction and use (mid fifteenth to sixteenth centuries), and destruction and re-use as a cemetery (sixteenth to seventeenth centuries) (Hirsch & Fauvelle-Aymar Reference Hirsch and Fauvelle-Aymar2002: 328; Derat & Jouquand Reference Derat and Jouquand2012; de Torres Rodríguez Reference de Torres Rodríguez2017: 244; Figure 4). Mobile royal camps existed until the early seventeenth century, when Gondär, north of Lake Tana (Figure 1), was established as a semi-permanent capital (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 260 & 263), occupied between c. 1632 and 1769. Archaeological research at Gondär has been minimal, with emphasis instead placed on the architectural and historical investigation of its churches and castles/palaces (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1979: 5; de Torres Rodríguez Reference de Torres Rodríguez2017: 225). The latter were influenced by Indian and Ottoman architecture (Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, de Torres, Martínez D'alòs-Moner and Cañete2017: 469–70), producing castle-like structures of unique form, with the earliest built by Emperor Fasiladas (1632–1667) (Wordekal Reference Wordekal1985: 119).

Figure 4. Amba Māryām, Mesḥāla Māryām (photograph by M.-L. Derat, Mission Mesḥāla Māryām, 1997).

European contact was also influential in the medieval period. Initially, what have been described as “precarious, but nonetheless continuous” (Tamrat Reference Tamrat1972: 267) relations were established between Ethiopia and Europe from the first half of the fifteenth century. Following an Ethiopian appeal for help during the jihad of Ahmad Gragn, a small Portuguese force arrived in 1541 under the leadership of Cristovaõ da Gama (Huntingford Reference Huntingford1989: 134). A correlate of the Portuguese presence was the co-appearance of the Jesuits (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 260), who, for a short period between the 1610s and 1620s, lived in the Lake Tana region and introduced their own architectural traditions. Three Jesuit sites in the Gondär region have been investigated: Gorgora Nova, Särka and Gännätä Iyasus (de Torres Rodríguez Reference de Torres Rodríguez2017; Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, de Torres, Martínez D'alòs-Moner and Cañete2017) (Figures 1 & 5). Notably, nothing specifically relating to the Jesuits was found, probably due to their short residence and subsequent re-use of the sites, with material all post-dating their occupation (de Torres Rodríguez Reference de Torres Rodríguez2017: 227–28; Fernández et al. Reference Fernández, de Torres, Martínez D'alòs-Moner and Cañete2017: 158–59 & 288). An indirect marker of the former Jesuit presence, however, is apparent at Gännätä Iyasus, where changes in ceramic forms illustrate a shift from communal to more individual patterns of food consumption in the mid seventeenth century. De Torres Rodríguez (Reference de Torres Rodríguez2017: 246) interprets this as evidence for elite strategies of social differentiation and to the legacy of Jesuit influences over foodways, which also included the consumption of pork— a practice forbidden in Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity. This Jesuit encounter also, ultimately, led to the self-imposed closure of the Christian kingdom to the outside world in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries (see González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2021), marking a decline in cosmopolitanism and the end of the narrative described here.

Figure 5. Church roof vault at Gorgora Nova, since collapsed (photograph by A. González-Ruibal).

Indigenous religions

Followers of Indigenous religions interacted with Muslim, Jewish and Christian populations and polities in medieval Ethiopia. This interaction is revealed through archaeological evidence indicating trade and exchange, such as the glass beads found in various medieval non-Muslim and Christian contexts (see Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021). The complexity and diversity of Indigenous religious belief and practice is also evident archaeologically, primarily through funerary monuments. Various stone cairns or tumuli (Daga Tuli), sometimes with circular burial chambers, were built and used between the eighth and twelfth centuries in the Tchercher Mountains. Some of the grave goods recovered from these tombs came from Red Sea trade—the source of Monetaria annulus cowry shells, Oliva sericea shells and large numbers of small blue, green, red and yellow glass beads (see Joussaume Reference Joussaume1980: pls XII–XIV; Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021). Diverse burial monuments, some again containing imported materials and artefacts, have also been found in the area of the Shay Culture of Shoa and in south-east Wallo, at sites such as Tätär Gur (Figure 1). These include tumuli, chamber tombs and dolmen graves dated to between the tenth and fourteenth centuries, when Islam and Christianity were both well established elsewhere in Ethiopia (Fauvelle & Poissonnier Reference Fauvelle and Poissonnier2016).

Megaliths were also erected in the medieval period in the region extending to the south of Addis Ababa and west of the Rift Valley Lakes (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 243). These are of varied forms, including phallic, figuratively carved or undecorated, and occur singularly and in groups (Joussaume Reference Joussaume1995: 102–103, Reference Joussaume2007; Derara Reference Derara2011). At Tiya, 50km south of Addis Ababa (Figure 1), many of the rhyolite 2–5m-high standing stones were carved with sword blade or lance-head symbols, or with ‘Y’-shapes that might depict genitalia or scarification marks (Derara Reference Derara2011: 72; Insoll Reference Insoll2015: 173; Figure 6). These stones are possibly from the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, based on dates from an associated cemetery (Joussaume Reference Joussaume1995: 148–52 & 286). This megalithic diversity and the practices that they represent lasted until the fifteenth century, when they disappeared, perhaps due to population displacement following the migration of the Oromo ethno-linguistic group into parts of Ethiopia (Finneran Reference Finneran2007: 248).

Figure 6. Standing stones at Tiya featuring carvings of with sword blades or lance-heads and ‘Y’-shapes (photograph by T. Insoll).

Special section

The research articles presented in the following section clearly demonstrate the power of archaeology to expand our knowledge of medieval Ethiopia and attest its complexity and cosmopolitanism. The chronology of Lalibela, for example, has been extended back in time. The Christian origins of the site have also been challenged through the identification of what is referred to as a ‘troglodytic’ culture, manifest also at Washa Mika'el, where pre-Christian iconography and space was appropriated and transformed to create the extant church (Derat et al. Reference Derat, Garric, Mensan, Fauvelle, Gleize and Goujon2021). In the western Ethiopian borderlands, ‘vernacular cosmopolitanism’ (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2021) was evident, with awareness of other religious systems, material worlds and cultural traditions, but within a framework of marginality, and one that changed over time. In medieval Harlaa, multiple strands contributed to a cosmopolitan urban culture, with Islamic heterogeneity apparent and religious plurality probable. Furthermore, trade and other networks extended far beyond eastern Ethiopia, both directly and indirectly incorporating people, ideas and trade goods (Insoll et al. Reference Insoll2021). In eastern Tigray, excavation of an Islamic cemetery has revealed the deep roots of a Muslim community within the Christian highlands, commencing in the late tenth century and continuing for 300 years, attesting both toleration and co-existence. Moreover, the community used iconographic traditions, suggesting widespread connections (Loiseau et al. Reference Loiseau, Dorso, Glieze, Ollivier, Ayenachew, Berhe, Chekroun and Hirsch2021).

As research increases, the temporality of cosmopolitanism in medieval Ethiopia will become better refined. This will likely reveal the episodic rather than continuous nature of cosmopolitanism, reflecting changes both inside Ethiopia and in the world beyond, as dynasties changed, trade routes shifted, commodities were exhausted, migrations occurred, wars were fought and religious rivalries and alliances came and went. It is perhaps this notion of cosmopolitanism, as something that can be transitory, that needed to be supported rather than assumed, which can be further explored in other archaeological contexts, and which might provide insights for sustaining the cosmopolitan world of today.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Rachel MacLean for comments on the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the European Research Council (grant BM694254-ERC-2015-AdG).