Population-based surveys have revealed that currently only about half of those people who have major depressive disorder are detected by regular healthcare. Reference Gilbody, House and Sheldon1 This seems unacceptable because depression is associated with poor health status and poor quality of life. Reference Rost, Zhang, Fortney, Smith, Coyne and Smith2 Screening in general practice populations has been advocated as a solution to this ‘hidden morbidity’. Reference Wright3 However, the positive predictive value of available screening instruments is too low in unselected groups of individuals. Reference Williams, Pignone, Ramirez and Perez4 Screening in high-risk groups might be a possible alternative in reducing the likelihood of undisclosed depression. 5

Furthermore, screening without feedback to general practitioners (GPs) has so far been of little value. Reference Gilbody, House and Sheldon6,Reference Pignone, Gaynes, Rushton, Burchell, Orleans and Mulrow7 General practitioners have indeed diagnosed more people with major depressive disorder, but this has not translated into more interventions or better outcomes. Therefore, screening should be implemented as part of a disease-management programme with identification of individuals, structured assessment of diagnosis, feedback of the diagnosis to the physician and availability of evidence-based treatments. Reference Pignone, Gaynes, Rushton, Burchell, Orleans and Mulrow7,Reference Gilbody, Sheldon and Wessely8

We defined the following high-risk groups in GP practices: individuals with mental health problems, individuals with unexplained somatic complaints and individuals who frequently attend their GP. Compared with the 10% prevalence of major depressive disorder for those presenting in a primary care setting, Reference Bauer, Bschor, Pfennig, Whybrow, Angst and Versiani9 the prevalence in these high-risk populations rises to about 20–30%. Reference Dowrick, Bellon and Gomez10–Reference Gill and Sharpe12 So far, no studies have evaluated the usefulness and effectiveness of this type of selective screening. Reference Gilbody, House and Sheldon1 We looked at how many people with undetected (or undiagnosed) major depressive disorder could be diagnosed and then be treated, when screening in predefined groups at high risk is applied in general practice. In this article the results of the initial screening, as part of a disease-management programme, in three high-risk groups are presented.

Method

Setting

The study was conducted as a prospective cohort study from January 2005 to March 2006 in primary care patients between 18 and 70 years of age, in two regions connected to academic settings in The Netherlands: the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam and the University Medical Centre St Radboud in Nijmegen. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics review committee of both centres.

Participants

Three high-risk groups were defined and selected from general practice populations.

People with mental health problems

All individuals who presented to their GP with a new mental health problem up to 3 months prior to the selection date were eligible. We selected individuals from the electronic patient database of the participating general practices. A time frame of 3 months was chosen because of the transitory nature of mental health problems. General pracitioners in our sample coded all diagnoses or complaints with the International Classification of Primay Care (ICPC) Reference Gebel and Lamberts13,Reference Lamberts and Wood14 classification. With the use of chapters P and Z of the ICPC, individuals were identified with a psychological or social reason for seeing their GP or a mental health diagnosis. To identify all people with possible mental health problems, the electronic patient database was also searched with the predefined free text-words: anxiety, worrying, sadness, stress, feeling down, and insomnia.

People with unexplained somatic complaints

These were identified as follows: people with somatic complaints that could not be explained in biological terms (determined by the GP) and in whom the duration of these unexplained somatic complaints was at least 90 days according to the GP. General practitioners checked their appointment lists during the 4 weeks preceding study allocation and selected individuals fulfilling both criteria.

People frequently attending their general practitioner

The method as proposed by Howe Reference Howe, Parry, Pickvance and Hockley15 was used to identify frequently attending individuals: the 10% of most frequently consulting women and the 10% of most frequently consulting men in two age groups (18–44 and 45–70 years) in the year preceding study allocation. With this method, differences in gender and age among people who attended frequently were accounted for. We used computerised attendance data from all consultations, home visits and telephone consultations with doctors, nurses and other team members. The highest 10% was determined separately for each GP because of differences in practice styles.

Follow-up procedure

General practitioners received a list of individuals selected by the research team. They excluded those people who were already recognised by the GP as having major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis or bipolar disorder, or were considered by the GP as not qualified to enter the study because of specific somatic problems (e.g. blindness, terminal illness) or intellectual disability. A last exclusion criterion was having trouble with the Dutch or English language.

Subsequently, an invitation letter signed by their own GP was sent to the people on the final list. The letter describing the study also contained an informed consent form and the screening instrument, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). Reference Spitzer and Kroenke16 If people did not respond within 2 weeks, a reminder was sent. A consecutive diagnostic interview for major depressive disorder (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I disorders, SCID–I) Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, Groenestijn, Akkerhuis, Kupka, Schneider and Nolen17 was performed with participants who had a PHQ–9 score ≥10.

Participants diagnosed in our study with any psychiatric disorder by SCID–I, were advised to consult their GP and to discuss the interview results and possible treatment options. General practitioners were also informed about the test results. If individuals did not contact their GP, they were telephoned 2 weeks later, asked why they had not done so and advised to try again. In The Netherlands, treatment for psychiatric disorders is covered by health insurance and is easily accessible.

Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) is a short self-report version of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME–MD). Reference Spitzer and Kroenke16 The full PHQ screens for the five most common mental disorders using DSM–IV 18 criteria: depressive disorders (major depressive disorder and dysthymia); anxiety disorders (panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder); alcohol abuse; somatoform disorder; and eating disorders (bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder). The PHQ–9 is the 9-item sub-scale for major depressive disorder. For identifying major depressive disorder we did not use the diagnostic algorithm, but a score ≥10 as this cut-off point proved to be more sensitive. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams19,Reference Wittkampf, Naeije, Schene, Huyser and van Weert20 Participants with a score ≥10 were assessed by telephone clinical interview (SCID–I) to make a definite diagnosis of major depressive disorder.

The SCID–I is a semi-structured interview designed for diagnosing mental disorders according to DSM–IV criteria. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, Groenestijn, Akkerhuis, Kupka, Schneider and Nolen17 Agreement between diagnosis gained from telephone and live administration of the SCID–I has been found to be excellent (Kappa=0.73 with 90% agreement). Reference Simon, Revicki and VonKorff21 The SCID–I was administered by researchers that received SCID–I training from a trained professional. Throughout the study all interviewers had ongoing training sessions supervised by an expert psychiatrist (J.H.). They also had monthly consensus meetings to maximise accuracy and consistency in the administration of the SCID–I. If the results of the mood disorder section of the SCID–I indicated a major depressive disorder, subsequent sections were checked in order to identify people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and psychosis. Individuals diagnosed with major depressive disorder were asked if they already received treatment, defined as pharmacotherapy with antidepressants and/or psychotherapy and/or structured and supportive care from the GP or from mental healthcare professionals.

Results

Identification of three high-risk groups

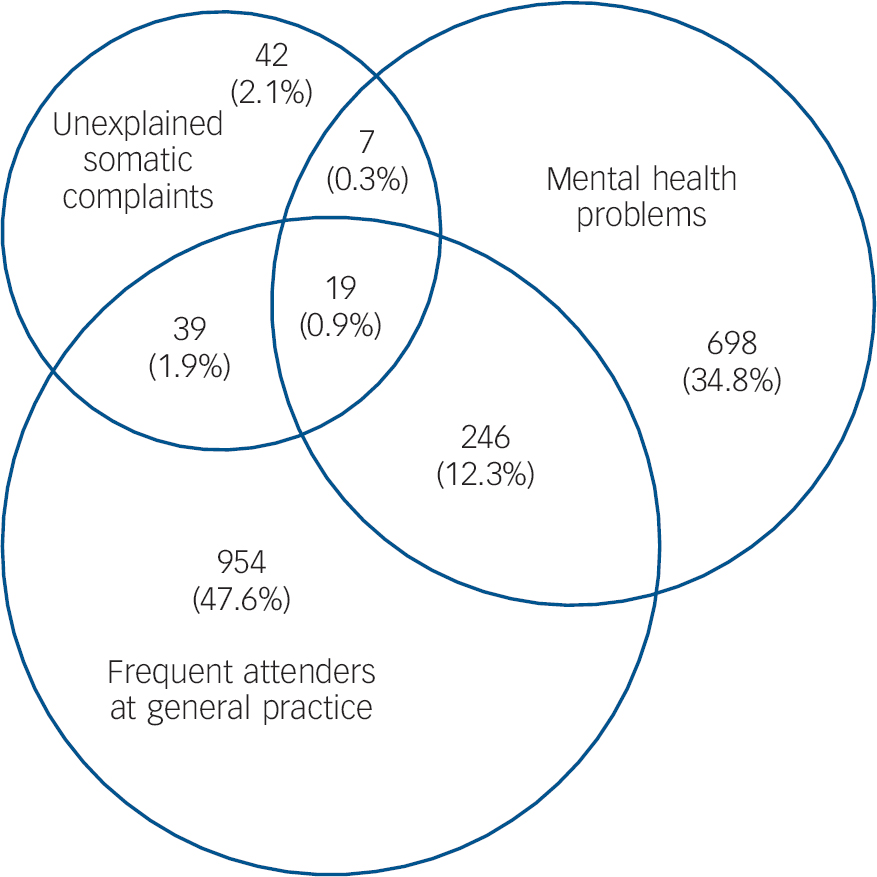

Three health centres with 12 GPs and 15 996 people on their lists participated. In total, 2005 people (12.5%) fulfilled the criteria for: frequently attending their GP (n = 1258); mental health problems (n = 970) and/or unexplained somatic complaints (n = 107) (Fig. 1). A total of 311 people belonged to two or three of the high-risk groups (Fig. 2).

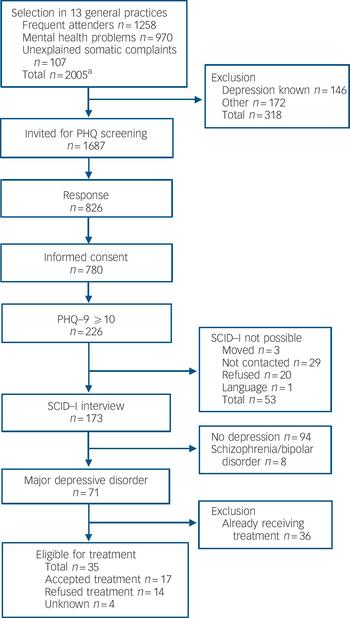

Fig. 1 Flow chart for the screening programme as the first step in a disease-management programme. PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ–9, Patient Health Questionnaire – nine-item subscale; SCID–I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I disorders. a. Smaller number because of overlap between groups, see Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Venn diagram showing absolute and relative (% of all) numbers of three high-risk groups (total n = 2005).

General practitioners excluded 318 (15.9%) individuals from screening: 146 (7.3%) were already known to have major depressive disorder by their GP and 172 (8.6%) were excluded for other reasons: diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (n = 18, 0.9%), terminal illness or intellectual disability (n = 44, 2.2%), and inability to understand Dutch or English (n = 110, 5.5%).

Effectiveness of screening

Of the 1687 people eligible for screening with the PHQ, 826 (49.0%) returned the questionnaire and of these 780 (94.4%) gave informed consent (Table 1). Individuals who gave consent were older, more often female and individuals from the mental health problems group were over-represented. Of the 780 people who gave consent, 226 (29%) had a PHQ–9 score ≥10 (Fig. 1); of these, 173 (76.5%) participated in the SCID–I interview. Reasons for non-participation (n=53) despite consent are described in Fig. 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of those invited to participate who gave informed consent for screening and those that refused to participate

| Participant characteristics | Informed consent (n=780) | Non-responders or no informed consent (n=907) | Total (n=1687) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 44.77 (12.72) | 41.52 (12.79) | 43.02 (12.85) | <0.0001a |

| Female, % (n) | 63.9 (499) | 53.5 (485) | 58.33 (984) | <0.0001b |

| High-risk group, % (n) | ||||

| Unexplained somatic complaints | 6.2 (48) | 5.4 (49) | 5.8 (97) | 0.50c |

| Mental health problems | 49.6 (387) | 44.3 (402) | 46.8 (789) | 0.03c |

| Frequently attend their GP | 60.6 (472) | 64.9 (589) | 62.9 (1061) | 0.06c |

Of the 173 SCID–I interviewed participants, 94 (54%) did not meet the criterion for major depressive disorder and 71 (41%) did. Another eight people (5%) met major depressive disorder criteria but also had psychosis and/or bipolar disorder according to DSM–IV. Thus, screening disclosed 79 additional individuals with major depressive disorder (9.6% of 826 who returned the PHQ and 4.7% of 1687 who were invited to participate). Neither age, gender, ethnicity nor high-risk group influenced the chance of diagnosing major depressive disorder, given a positive PHQ screening (Table 2).

Table 2 Participants who scored 10 or higher on the PHQ–9: comparison of those with major depressive disorder and those without major depressive disorder according to SCID–I

| Participant characteristics | Major depressive disorder (n=79) | No major depressive disorder (n=94) | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: % (n) | 0.36a | |||

| 18-24 | 5.4 (4) | 10.8 (10) | 8.4 (14) | |

| 25-44 | 48.7 (36) | 40.8 (38) | 44.3 (74) | |

| 45-64 | 45.9 (34) | 48.4 (45) | 47.3 (79) | |

| Gender, % (n) | 0.23a | |||

| Female | 77.2 (61) | 69.2 (65) | 72.8 (126) | |

| Male | 22.8 (18) | 30.8 (29) | 27.2 (47) | |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | 0.97a | |||

| White | 78.4 (58) | 78.6 (70) | 78.5 (128) | |

| Other | 21.6 (16) | 21.4 (19) | 21.5 (35) | |

| High-risk group, % (n) | ||||

| Unexplained somatic complaints | 10.1 (8) | 10.6 (10) | 10.4 (18) | 0.91b |

| Mental health problems | 56.9 (45) | 58.5 (55) | 57.8 (100) | 0.83b |

| Frequently attend their GP | 55.1 (43) | 57.5 (54) | 56.4 (97) | 0.76b |

Of the 71 individuals identified with major depressive disorder, 36 (51%) already received treatment. Of the 35 (49%) new cases eligible for treatment, 14 (40%) refused treatment after they received information about the diagnosis and treatment from their GP. Despite repeatedly made appointments, another four individuals (11%) did not show up for an appointment with their GP.

At the final result of the screening and diagnostic phase of our programme, 17 individuals were eligible to receive treatment for major depressive disorder. To treat these 17 people, we had to invite 1687 people for screening, 780 of whom participated in screening. The number needed to invite to treat 1 additional major depressive disorder is 99 (17/1687), the number needed to screen is 46 (17/780) and the number needed to screen to treat 1 not yet diagnosed major depressive disorder was 118 (17/2005).

Discussion

We have reported on the yield of the initial steps in a disease-management programme for major depressive disorder, consisting of selective screening of patients belonging to three high-risk groups, followed by structured diagnosis and feedback, followed by offering treatment. Among 2005 identified people at high risk, the selective screening diagnosed 71 new individuals with major depressive disorder. Of these, 36 already received some kind of treatment, 14 refused treatment and 17 accepted treatment. We concluded that with the need to screen 118 people to treat 1 additional person with depression, this type of screening has no or only very limited effect.

The effect could have been greater if the number of detected individuals refusing treatment (n=14) could have been reduced. General practitioners gave individuals psychoeducation for depression and all of them received a brochure (provided by the Dutch College of General Practice) about depression. We think that this amount of information about depression is adequate for making a decision about treatment. The people who refused treatment were well informed.

Another issue is the possible health gain that could have been achieved by the treatment of the 17 participants who accepted treatment. Considering that the natural course of depression in general practice is about 3 months, Reference van Weel-Baumgarten, van den, van den and Zitman22 that the severity of depression of these 17 was moderate (mean Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score 19), that the number needed to treat for antidepressants is between 6 and 10, although recent papers show that there seems little evidence to support the prescription of antidepressant medication to individuals other than the most severely depressed, Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson23 we conclude that treatment of these 17 participants would have resulted in small health gains in comparison with care as usual. Furthermore, it has been shown Reference Kendrick24,Reference Kessler, Bennewith, Lewis and Sharp25 that a number of missed cases are diagnosed at later visits, although others have suggested that some of the low severity cases found by screening are false positives because all diagnostic measures have rating errors. Reference Thompson, Ostler, Peveler, Baker and Kinmonth26

One can speculate whether our predefined high-risk groups were adequately chosen. We think they were, although we could not replicate the 20–30% major depressive disorder prevalence mentioned above. We found a total prevalence of 18%: 7% (n=146) that were already known by their GP as having major depressive disorder and another 11% with not yet diagnosed or undetected major depressive disorder (extrapolated from the cases found by screening the total high-risk group), figures in accordance with some earlier research. Reference Pignone, Gaynes, Rushton, Burchell, Orleans and Mulrow7,Reference Ormel, Koeter, van den and van de27,Reference Simon, Goldberg, Tiemens and Ustun28

A main criticism of screening in primary care is the cross-sectional nature of screening. In a longitudinal study, as discussed above, most of the individuals with undisclosed depression might be identified at a later date. A number of our predefined high-risk individuals were already visiting their GP regularly. Despite this fact, major depressive disorder was not yet diagnosed which at least partly parries this criticism.

Half of the patients did not respond to the letter inviting them to participate despite them being invited by their own GP to enhance participation. In comparison with other screening programmes (e.g. cervical cancer (about 80% response), breast cancer (90–95% response)) this response rate is quite low. This might be caused by the nature of the targeted disorder or the nature of the screening instrument. However, participation of about 50% is not unusual in psychiatric programmes. Reference Greil, Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Steller, Czernik, Giedke and Muller-Oerlinghausen29 Furthermore, a recent survey showed that patient inclusion in research when the GP was the patient's informant about the study was less successful than when the patient received a mailed letter about the study signed by their GP. Reference van der Wouden, Blankenstein, Huibers, van der Windt, Stalman and Verhagen30

Finally, even with the methods we used, participating GPs felt the screening procedure placed an additional high burden on their regular practice and they experienced disturbance of their daily routine.

Of the people who responded, 94.4% gave informed consent. As could be expected, response rates were higher in the group of individuals with mental health problems than in the other groups. Individuals with mental health problems addressed their GP because of the need for treatment. Reference Arroll, Goodyear-Smith, Kerse, Fishman and Gunn31 At this time we do not have a valid explanation for the fact that people were willing to go through the complete procedure of screening and diagnosis, but refused treatment. One explanation is that they did not fully understand the screening procedure and/or its possible consequences. Another explanation might be that people who screened positive, but did not agree to treatment, did not accept a psychiatric diagnosis or label or were not in a hurry to seek help. Reference Arroll, Goodyear-Smith, Kerse, Fishman and Gunn31 This phenomenon is new and needs to be further explored.

Limitations

A limitation might be that we assumed a 100% sensitivity of the PHQ–9. We did not attempt to detect depression among those people with a score <10. Therefore, we have probably missed some individuals with major depressive disorder. With a 0.88 sensitivity of the PHQ–9 for major depressive disorder, we might have missed 18 individuals with depression, resulting in 4 (16/71 × 18) additional people accepting treatment. This would not have changed our results significantly because the PHQ also measures severity of depression, and with a score smaller than 10 these individuals are likely to have less severe depression. Moreover, higher sensitivity would result in lower specificity, thereby dramatically increasing the number of false positives. Reference Henkel, Mergl, Kohnen, Maier, Moller and Hegerl32

Implications for practice

Screening of high-risk groups for depression in general practice is feasible when the number of newly detected people is the outcome. It is not feasible when the number of individuals that actually will receive treatment (and might be helped) is the primary outcome. Therefore, in contrast with prior suggestions, the problem is not so much a lack of resources or training and education of GPs, but the unwillingness of individuals to accept treatment for a condition they did not present with to their GP. The key to improving care lies, therefore, not in recognising undisclosed depression only, but in convincing individuals to initiate and thereafter continue with evidence-based treatment for major depressive disorder. Recently, more thorough organisational strategies such as case management have been recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 5 Recent reviews and randomised controlled trials have established the effectiveness of these organisational strategies. Reference Gilbody, Whitty, Grimshaw and Thomas33–Reference Gensichen, Beyer, Muth, Gerlach, Von Korff and Ormel35 Future studies should focus on the effectiveness of case management in these specific high-risk groups. A non-medical approach that at first abstains from the label of depression has to be considered here. Screening for depression in high-risk populations in general practice does not appear to be effective even if treatment is freely and easily accessible for two reasons: the total amount of time to execute the screening procedure (including quite a lot of GP time) and the low rates of treatment initiation in combination with the limited health gain per treated case.

Funding

This study was financed by a grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), programme Mental Health (no. 100.003.005 and 100.002.021).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.