Person-centred care (PCC) is a philosophy of care rooted in humanism (Fazio, Pace, Flinner, & Kallmyer, Reference Fazio, Pace, Maslow, Zimmerman and Kallmyer2018) that emphasizes autonomy, identity, and respecting individual preferences regarding care decisions and practices (Fazio, Pace, Flinner, & Kallmyer, Reference Fazio, Pace, Maslow, Zimmerman and Kallmyer2018). The Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America (2001) deemed PCC a key component of care quality. Further, increasing PCC practice is considered to be essential to both the quality of care and quality of life of people residing in residential care homes (RCHs) (homes in which 24 hour nursing care is provided to residents with complex care needs), especially those living with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007; Fazio, Reference Fazio2008; Fazio, Pace, Maslow, Zimmerman, & Kallmyer, Reference Fazio, Pace, Maslow, Zimmerman and Kallmyer2018; Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2017; Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997).

Over the course of the last two decades, PCC has become recognized asbest practicein dementia care, with the majority of RCHs having proclaimed it as the care philosophy to which they subscribe (Caspar, O’Rourke, & Gutman, Reference Caspar, O’Rourke and Gutman2009). However, researchers continue to find that care in RCHs tends to be more task-focused than person-centred (Beck, Klein, & Kahn, Reference Beck, Klein and Kahn2012; Furaker & Nilsson, Reference Furaker and Nilsson2009), that individually tailored meaningful activities are not the norm (Kirkevold & Engedal, Reference Kirkevold and Engedal2006; Wood, Womack, & Hooper, Reference Wood, Womack and Hooper2009), and that few possibilities for resident choice exist in daily care and activities (Berglund, Reference Berglund2007; Kirkevold & Engedal, Reference Kirkevold and Engedal2006; Luff, Ellmers, Eyers, Young, & Arber, Reference Luff, Ellmers, Eyers, Young and Arber2011; Schnelle et al., Reference Schnelle, Bertrand, Hurd, White, Squires and Feuerberg2009). The literature indicates that meaningful improvements in the provision of PCC in RCHs have been largely unrealized, despite significant effort to alter practice (Doty, Koren, & Sturla, Reference Doty, Koren and Sturla2008; Elliot, Cohen, Reed, Nolet, & Zimmerman, Reference Elliot, Cohen, Reed, Nolet and Zimmerman2014; Grabowski, Elliot, Leitzell, Cohen, & Zimmerman, Reference Elliot, Cohen, Reed, Nolet and Zimmerman2014).

Research in RCHs demonstrates that interventions aimed at increasing the provision of PCC that do not address contextual and system issues (e.g., deeply rooted care routines and regulatory standards that impede individuality, resident choice, and staff flexibility), most often fail (Caspar, Cooke, Phinney, & Ratner, Reference Caspar, Cooke, Phinney and Ratner2016). There is growing evidence demonstrating that the implementation of PCC in practice necessitates a multi-level, systems approach (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007; Evans, Reference Evans2017; Manthorpe & Samsi, Reference Manthorpe and Samsi2016). Thus, it is reasonable to assert that promoting positive change in the residential care context requires more than education; it requires the engagement of key stakeholders who have the potential to facilitate change in the system as a whole.

PCC encompasses all aspects of care; however, we purposefully selected mealtimes as a focus for this study. Malnutrition is a real and pressing issue for people with dementia (PWD) (Keller, Reference Keller2016), and many determinants of food intake (e.g., familiarity and “homelikeness”, optimal sensory stimulation, social interaction) are inextricably linked with the mealtime experience (Chaudhury, Hung, Rust, & Wu, Reference Chaudhury, Hung, Rust and Wu2016). Previous research indicates that nursing staff in RCHs tend to focus on the mechanical task of eating assistance but overlook the psychosocial aspects of residents’ experiences during mealtimes (Henkusens, Keller, Dupuis, & Schindel Martin, Reference Henkusens, Keller, Dupuis and Schindel Martin2014; Penrod et al., Reference Penrod, Yu, Kolanowski, Fick, Loeb and Hupcey2007). These task-oriented approaches not only impede the enjoyment of dining, they can also negatively impact the dignity and personhood of PWD (Kirkevold & Engedal, Reference Kirkevold and Engedal2006). Studies examining the importance of food and mealtime in dementia care have identified that person-centredness in mealtime activities, such as preparing food, participating in menu planning, and family inclusion, can sustain the identity of PWD (Ducak, Sweatman, & Keller, Reference Ducak, Sweatman and Keller2015; Keller, Edward, & Cook, Reference Keller, Edward and Cook2007; Lam & Keller, Reference Lam and Keller2015; Reimer & Keller, Reference Reimer and Keller2009). Therefore, as regular, frequent, and discrete events, mealtimes provide meaningful opportunities to study the effects of interventions aimed at increasing the provision of PCC practices.

Our aim was to create and implement a practice change initiative to improve PCC in RCHs, which emphasizes engagement of key stakeholders (e.g., care staff members, administrators, family members, PWD). As stated previously, mealtimes were selected as the central focus for this study. Therefore, in our efforts to achieve our study aim, we documented, analyzed, and evaluated both the process and the outcomes of implementing a change initiative for promoting person-centred mealtimes in RCHs.

The specific objectives of this study were to:

1. Examine the influence of a stakeholder engagement practice change initiative on outcomes associated with the physical environment, social environment, and relationship and PCC practices during mealtimes.

2. Examine the acceptability of the stakeholder engagement practice change initiative to study participants, including a qualitative assessment of the change processes as well as enablers and barriers to the implementation of the changes in mealtime care practices.

In what follows, we describe in detail our evaluation of both the process and the outcomes of the practice change initiative.

Methods

Using principals consistent with Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) (Torre, Fine, Stoudt, & Fox, Reference Torre, Fine, Stoudt and Fox2012), we collaborated with those experiencing organizational practices that supported or impeded care staff members’ ability to provide PCC during mealtimes in RCHs. This included management and care providers within a RCH and family members of residents within the RCH. These individuals were key decision makers as well as research participants in the project. A single-group, time series design with repeated measures was used to assess the impact of the practice change initiative on outcome measures across four time periods (pre-intervention, and 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up). Observations and interviews were also conducted to examine treatment fidelity and to ascertain the study participants’ perceptions of the process and outcomes of the intervention.

Setting and sample

This study was conducted in a RCH located in Western Canada. Convenience sampling, based on partner engagement and needs, was employed for site selection. The participating RCH provided long-term care, rehabilitation services, supportive living care, and palliative care to approximately 200 residents. The unit within which the practice change initiative was implemented was home to 12 residents, all of whom were male and had a diagnosis of dementia. The unit was secured (i.e., residents were unable to enter or exit the unit unaccompanied) and was one of four units on a single floor in the RCH. The administrator of the RCH had the ultimate decision regarding which unit was selected for participation in this study. He informed the research team that he selected this unit because of the smaller number of residents living in it and the high level of family involvement.

Health care aides (HCAs) provided the majority of direct care to the residents on this unit and were supervised by licensed practical nurses (LPNs). Although assigned to a specific floor, the HCAs only stayed on the unit for three to four shifts (days and evenings) before rotating onto the other three units on the floor. As a result of this scheduling practice, upon completion of their shifts, the HCAs would not provide care to residents living in this unit again for approximately 3 weeks.

The HCAs and LPNs on the floor were supervised by a care manager who was trained as a registered nurse (RN); however, this position became vacant on the first day of participant recruitment and was not filled throughout the duration of the study. Additionally, at approximately the mid-point of the study, the administrator of the RCH was relocated to a new position within the organization, and interim administrators filled this position for the remaining portion of the study. The lack of continuity, both in leadership and in staffing assignments, provided us with an especially challenging context within which to try to produce sustainable changes in care practices. However, because of our extensive direct experience working in RCHs, we were aware that this context was not altogether unique (i.e., assignment practices vary greatly in RCHs and management turnover is not uncommon in this industry).

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Alberta ethics review board. Following ethics approval, the research assistant (RA) and the principal investigator (PI) provided several study information sessions to family members and care staff members at the RCH. During these information sessions, study participants provided signed, informed consent to participate. Family members of residents living with dementia provided consent on behalf of the residents. However, the RA also ensured that residents consistently demonstrated assent during each of the observation periods (Slaughter, Cole, Jennings, & Reimer, Reference Slaughter, Cole, Jennings and Reimer2007). Because of the nature of the study design, the RA continued to recruit and receive informed consent from study participants over the course of the entire study. Specifically, any care staff member, family member, or resident who did not provide consent during the study information sessions, but who was present for a mealtime observation period (e.g., new or casual care staff members) was individually informed about the study and was given the opportunity to provide consent or assent, or to decline participation in the study prior to the observation period beginning. In an attempt to ensure complete anonymity during the observation periods, and because of the nature of our participant recruitment methods and outcome measures used (i.e., no surveys were completed by study participants and observations were conducted in the general dining area during multiple mealtimes), participant baseline demographic data were not collected from study participants.

During the study information sessions, participants were also invited to become active members of the Process Improvement Team (PIT). Care staff members and family members self-selected themselves to become members of the PIT and, by doing so, took a leadership role in the practice change initiative. The PI and RA insured that representatives from all key stakeholder groups were included in the PIT. Upon completion of recruitment, the PIT was composed of four HCAs, two LPNs, three dietary staff members (the hospitality manager, the dietary manager, and one galley aide), two family members, one recreation therapist, and the RCH administrator.

Description of Intervention: A New Model for Practice Change

The practice change initiative used in this project drew significantly from the model for improvement developed by Langley et al. (Reference Langley, Moen, Nolan, Nolan, Norman and Provost2009). The model for improvement provides a method for stakeholder engagement and the means to evaluate, advance, and continually learn from changes to care practices that are made. Under this approach, the PIT was formed to actively engage key stakeholders to co-develop clearly defined strategies for practice change and then implement these changes through plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycles.

We expanded on the model for improvement by adding two key features (see Appendix for a list of each step of the Feasible and Sustainable Culture Change Intervention [FASCCI] Model). First, during the PIT meetings, we applied skills from an evidenced-based leadership training (Caspar, Le, & McGilton, Reference Caspar, Le and McGilton2017a) to strengthen the collaborative decision-making and communication skills among the PIT members. The second feature was the active exploration, selection, and application of three key intervention factors that help to increase the feasibility and sustainability of a change initiative (Caspar et al., Reference Caspar, Cooke, Phinney and Ratner2016). These include predisposing factors (e.g., effective communication and dissemination of information), enabling factors (e.g., conditions and resources required to enable staff members to implement new skills or practices), and reinforcing factors (e.g., mechanisms that reinforce the implementation of new skills) (Caspar et al., Reference Caspar, Cooke, Phinney and Ratner2016).

Throughout the change process, the research team was able to identify challenges and adapt and revise the practice change initiative as necessary in order to enable and sustain the changes in care practices. Upon completion of the study, the developed model for change included 12 steps for implementation:

1. Deciding to make a change.

2. Forming the team: Including the right people on a PIT, which is composed of those who work in the system and is critical to a successful improvement effort. A PIT team composed of key stakeholders associated with the selected area of change (i.e., care staff members, family members, administrators, managers, and interdisciplinary care team members) is formed.

3. Educating the team: Educating the PIT members on current best practices associated with the selected area of change.

a. Research demonstrates that training is needed to support mealtimes with a person-centred, social focus (Ducak et al., Reference Ducak, Sweatman and Keller2015; Reimer & Keller, Reference Reimer and Keller2009); this training needs to emphasize the importance of the social aspects of meals (e.g., communicating with residents in an affective, or personal, way that promotes relationships) (Reimer & Keller, Reference Reimer and Keller2009). Thus, PIT members received training on CHOICE principles. CHOICE is an evidence-based knowledge translation program used to support relationship centred-dining in long-term care (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Morrison, Dunn-Ridgeway, Vucea, Iuglio and Keller2018). The principles of CHOICE include: Connecting, Honouring Dignity, Offering support, Identity, Creating opportunities and Enjoyment (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Morrison, Dunn-Ridgeway, Vucea, Iuglio and Keller2018).

4. Creating a shared vision: Following the education session, the PIT members actively engage in creating a shared vision for mealtimes.

5. Selecting specific changes in care practices: Ideas for changes in care practice come directly from the PIT members.

6. Developing strategies associated with three key intervention factors (Caspar et al., Reference Caspar, Cooke, Phinney and Ratner2016): The PIT members select and enact the requisite predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that address the selected changes in care practice. This critical thinking on how to make the change is essential to the success of the project.

7. Establishing measures: Measurement is a critical part of testing and implementing changes. Outcome measures and process assessments are used to determine if specific changes actually lead to improvements.

8. Testing changes: The PDSA cycle, which is shorthand for testing a change in the real work setting by planning, testing, observing the results, and acting on what is learned. Several PDSA cycles are conducted throughout the change initiative.

9. Conducting weekly PIT meetings: These weekly meetings are key to the success of the project. Facilitators of the meetings apply leadership skills as presented in the responsive leadership training (Caspar et al., Reference Caspar, Cooke, Phinney and Ratner2016) (e.g., strategies to improve information exchange, collaboration, and timely follow-up to concerns). PIT meetings last approximately 20 minutes and meeting minutes with follow-up action items are documented for each meeting. These minutes are shared with everyone on the care team.

10. Celebrating and communicating successes!

11. Implementing changes: After testing a change on a small scale, learning from each test, and refining the change through several PDSA cycles, the teams implement the change as a permanent way of providing PCC on the unit.

12. Spreading changes: After successful implementation of a change or package of changes on an entire unit, the teams then begin to spread the changes to other parts of the organization.

Implementation Overview

Following participant recruitment and the PIT formation, members of the PIT participated in two workshops led by Dr. Caspar. The first workshop was a 4-hour education session that included the CHOICE training materials (Wu et al., 2018). Approximately 1 week later, the PIT members participated in a half-day workshop, during which they selected the person-centred mealtime strategies that they wished to implement. Each of the selected strategies was associated with the principles presented in the CHOICE education session. In total, 17 person-centred mealtime strategies were selected by the PIT members. Table 1 provides a list of each of the strategies and the corresponding CHOICE principle with which it is associated.

Table 1: Selected mealtime strategies

Following this, the PIT members with the guidance of the PI acting as a facilitator, determined the predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that they deemed necessary for their successful implementation of these strategies. The PIT members then engaged in weekly 20-minute meetings to monitor success and collaborate for solutions to any barriers that may have been preventing them from implementing the selected person-centred mealtime strategies. The weekly PIT meetings were facilitated by the PI and continued for the full 6 months of the study. Mid-way through the study, the PIT members attended a 4-hour, mid-study celebration during which we reviewed and celebrated our successes to that point. During this meeting, the PIT members selected additional mealtime strategies to implement and began discussions about how to sustain and spread the change initiative. After the completion of data collection, an end-of-study celebration was held for all PIT members. Following the end-of-study celebration, the PI provided a 4-hour training session on responsive leadership skills to PIT members who emerged as leaders during the study. To support the sustainability of the outcomes, all LPNs and managers at the RCH who wanted to participate were also included in this leadership training session.

Outcome Assessment

Measures

To understand the impact of the practice change initiative on outcomes associated with the mealtime experience, multiple mealtime observations were completed with the Mealtime Scan (MTS) (Keller, Awwad, Morrison, & Chaudhury, Reference Keller, Awwad, Morrison and Chaudhury2019). This observational tool is a valid and reliable assessment that measures the psychosocial environment, as well as physical aspects of a dining environment that impact the mealtime experience (Iuglio et al., Reference Iuglio, Keller, Chaudhury, Slaughter, Lengyel and Morrison2018; Keller, Chaudhury, Pfisterer, & Slaughter, Reference Keller, Chaudhury, Pfisterer and Slaughter2018). The MTS+ provides further detailed observation on the social environment and improved scaling to promote responsiveness on repeat measurement (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Awwad, Morrison and Chaudhury2019). The MTS+ includes four summative scales that assess (1) the physical environment, (2) the social environment, (3) person/relationship-centred care, and (4) the overall quality of the dining environment. The maximum score for each of the four MTS+ summative scales is 8.

Data collection

Thirty-eight mealtime observations were completed over the course of 6 months in a single dining room, with 5 observations at baseline, 9 at 1 month, 10 at 3 months, and 14 at 6 months. Observations represented different mealtimes at the RCH, with 19 observations during lunchtime, 18 during suppertime, and 1 during breakfast. These observations were done for the duration of the mealtime (usually 30–60 minutes). As recommended for MTS+ (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Awwad, Morrison and Chaudhury2019), the same assessor (E.D.) completed all assessments throughout the study to promote consistency. The assessor was acclimatized to the RCH before observations began and ensured that she remained as inconspicuous as possible. Although care team members may be “reactive” to observers, this effect is estimated to have only about a 10–20 per cent effect size (Romanczyk, Kent, Diament, & O’Leary, Reference Romanczyk, Kent, Diament and O’Leary1973).

Analytic approach

Each of the four MTS+ summative scales was tested for normality and described (mean, standard deviation) by time point. Changes from baseline were evaluated utilizing Mann–Whitney U pairwise tests with a Bonferroni correction, because the assumptions were not met for parametric statistics and the sample size was relatively small. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistical Software (Version 25).

Treatment Fidelity Assessment

Consistent with recommendations by Slaughter, Hill, & Snelgrove-Clarke (Reference Slaughter, Hill and Snelgrove-Clarke2015), treatment fidelity was monitored by assessing dose, adherence, and participant responsiveness.

Assessment of dose

We assessed dose by keeping detailed records of the number of participants at each of the education sessions and the subsequent weekly PIT meetings. We also recorded the number and length of PIT meetings that occurred through the duration of the study.

Assessment of adherence

Assessment of adherence occurred during each of the PIT meetings. The selected mealtime strategies and their requisite predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors (which were developed by the PIT members to enact each of the CHOICE principles) were reviewed and analyzed at every PIT meeting. As a result of this analysis, PIT members were enabled to assess challenges to (and deviations from) the selected changes in care practice, and then collaboratively identify solutions to address those challenges via the PDSA cycles. Detailed meeting records enabled us to chart the progress of changes made to the mealtime experience of the residents.

Assessment of responsiveness

To better understand the PIT members’ experiences regarding the practice change initiative, the research associate (E.D.) also conducted semi-structured interviews (lasting approximately 1 hour). The methodological approach that guided these interviews came from Smith (Reference Smith2005), who asserts that adhering strictly to an interview script limits the researcher to what s/he has already anticipated and hence forestalls the process of discovery. Accordingly, the interviews began with basic questions such as, “Tell me about your experiences during this change initiative?” followed by “What do you believe has helped the change initiative succeed?” and “Tell me about what has troubled or frustrated you during this change initiative?” Following this method, all other question evolved out of the course of the interviews/conversations as they would normally arise (Smith, Reference Smith2005). In total, 21 interviews were conducted. To better understand potential changes in perspectives as the initiative progressed, we conducted 12 interviews at the mid-point of the change initiative and 9 at the conclusion of the change initiative. All interviews lasted approximately 1 hour, were conducted in a private location, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analytic approach

The principal investigator used Microsoft Word to manage and group the data from the interviews. The decisions regarding how the data were to be grouped were not predetermined. Rather, they evolved from a review of the transcribed interviews and the detailed notes taken during the PIT meetings. The focus of the analysis of the qualitative data was not on discovering themes; rather, we aimed to discover, from the perspective of the participants, what was working regarding the implementation of the practice change initiative and what was not.

Results

Changes in Mealtimes

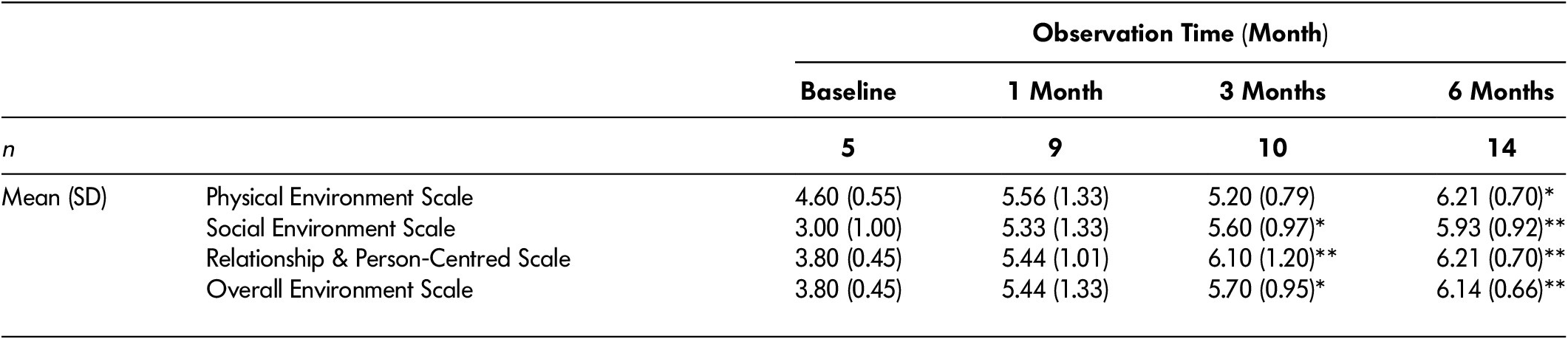

Statistically significant improvements were noted in all mealtime environment scales by 6 months, including the physical environment (z = -3.06, p = 0.013), social environment (z = -3.69, p = 0.001), relationship and person-centred scale (z = -3.51, p = 0.003), and overall environment scale (z = -3.60, p = 0.002). In fact, mealtime environment scores started increasing immediately following the intervention, with statistically significant improvements noted as soon as 3 months following the intervention for social environment (z = -2.93, p = 0.020), the relationship and person-centred scale (z = -3.30, p = 0.006), and the overall quality of dining environment scale (z = -2.70, p = 0.042). Means and standard deviations for all mealtime environment scale scores are reported in Table 2.

Table 2: Mealtime environment improvement throughout intervention

Note. Baseline serves as the reference category for Mann–Whitney U pairwise statistical tests with a Bonferroni correction; SD = standard deviation; *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01.

Physical environment

MTS+ assessment of the physical environment includes such mealtime elements as noise levels, seating arrangements, sufficiency of lighting, aroma of food, decorations and ambiance, and availability of condiments for residents to choose from. Almost all elements of the physical environment showed significant improvement as a result of the intervention. For example, baseline observations demonstrated that, prior to the intervention, the television was on during 60 per cent of the observed meals, condiments were not placed on the tables, and the tables were set (with napkins and utensils) for only 20 per cent of the observed meals. Whereas, at the conclusion of the intervention, the television was off and was replaced with soft background music during 100 per cent of the meals, condiments were on tables for 60 per cent of the meals, and the tables were set for 100 per cent of the observed meals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Physical Environment

As demonstrated in Figure 1, adequate light levels during mealtimes had also improved by the final observations. One component of the physical environment that did not show improvement was food aroma. This was because the food was prepared off-site and this did not change as a result of the intervention. Although not measured on the MTS+, it is also important to note that, prior to the intervention, meals were provided to residents on trays. One of the first changes that the PIT members implemented was the removal of the trays. Within 2 weeks of the implementation of the change initiative, the residents were served their food on plates, which were placed on tables that they had assisted in setting.

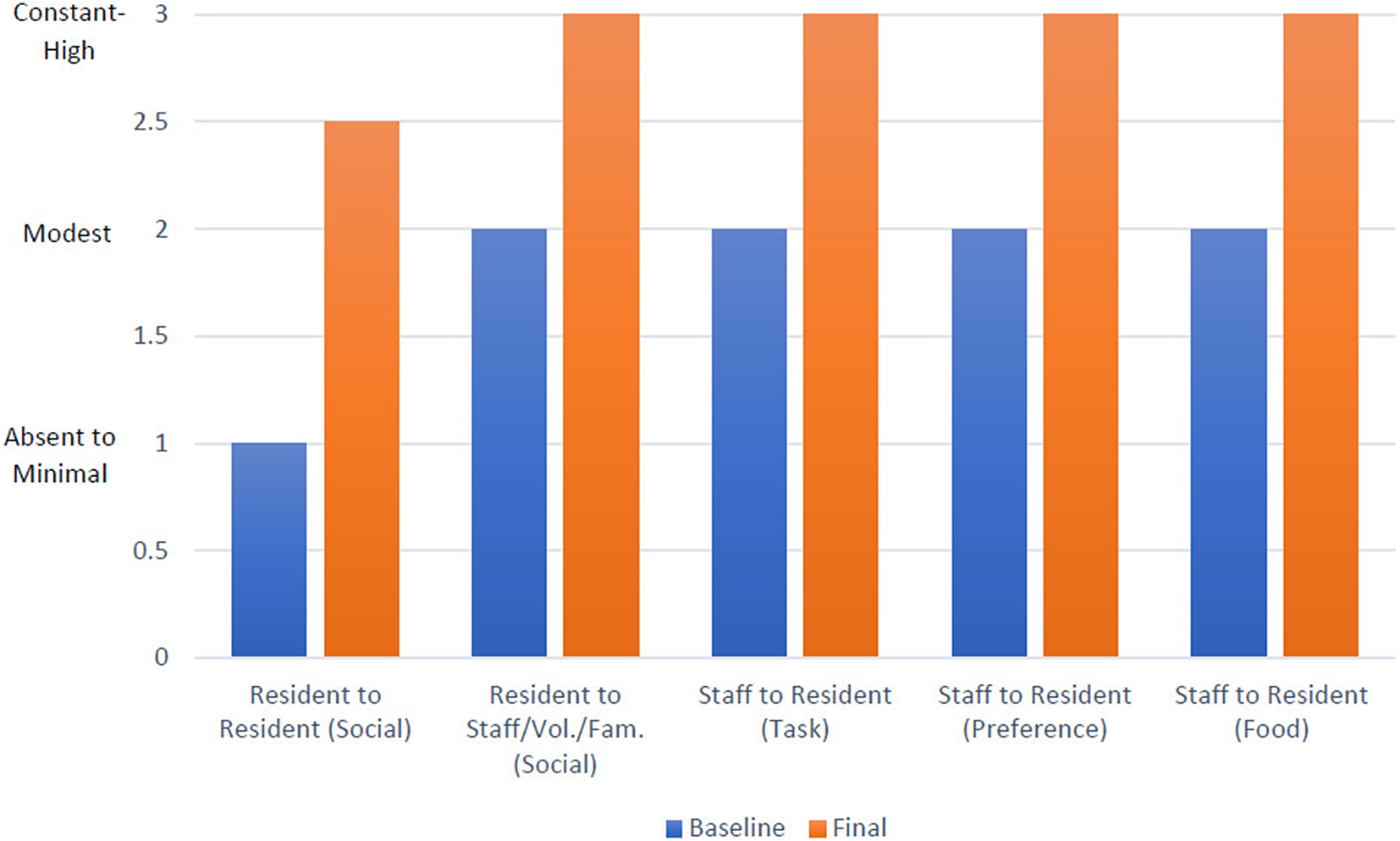

Social environment

The social environment is assessed based on the quality/type of five social interactions (e.g., between residents, between residents and staff, staff to staff) and their frequency. Ratings (0 = never, 4= frequent) are based on the frequency of the interaction as observed, and scoring for the social environment scale is based on the predominance of social interactions that involve residents in contrast with task-focused interactions that exclude residents. Resident-to-resident interactions improved over the course of the intervention, as did other positive interactions, such as staff interacting with affection to residents. Task-focused interactions were reduced, resulting in an overall increase in the social environment score over time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Social Environment

PCC

PCC practices are primarily evaluated by assessing the degree of choice given to residents regarding mealtime activities (e.g., did they have the opportunity to assist with mealtime tasks, were they given a choice of where to sit, were they offered a choice regarding use of clothing protectors) and whether or not the residents’ needs were prioritized over the mealtime care tasks (e.g., was the meal interrupted by the distribution of medications, were residents needs met when they became evident to staff). Significant improvements were made in all aspects of PCC following the intervention. For example, prior to the intervention, residents were not given a choice regarding where they sat, whether or not a clothing protector was worn, or what beverage they received during the meal. Following the intervention, choice was offered for each of these mealtime activities during 100 per cent of the observed meals. Additionally, prior to the intervention, residents were not enabled to assist with setting the tables nor were staff enabled or encouraged to sit with residents and socialize during meals. Following the intervention, staff was noted to sit and socialize with the residents during 70 per cent of the observed meals and one or more residents assisted with setting and clearing the table during 100 per cent of the observed meals. Despite significant effort to alter practice, only slight improvements were made to how often medications were distributed at meals in a disruptive manner (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Person-centred Care

Treatment Fidelity and Acceptability of the Change Initiative to Participants

Multiple methods were used to assess treatment fidelity and the acceptability of the practice change initiative to study participants. This section will report our assessment of dose, adherence, and PIT members’ perceptions of the practice change initiative.

Assessment of dose

During the study, PIT members attended four half-day sessions (two education sessions at the start of the study, one combined celebration and education booster session at the mid-point of the study, and one end-of-study celebration at the conclusion of the study). Attendance of these sessions ranged from 80 to 100 per cent of the PIT members.

In total, 29 PIT meetings occurred over the course of the study. These meetings lasted on average 20 minutes each and were held once weekly, on a set day, time, and location at the RCH. On average, 80 per cent of the members were present at each meeting. This was only possible because HCAs and LPNs would come in on their days off (without compensation) to attend the meetings. We certainly did not anticipate this, nor did we communicate to the PIT members that coming in to attend the meetings on their days off was expected. The PIT members who attended the fewest meetings included the administrator (who attended less than 20% of the meetings), one family member (who was still working full time and therefore attended less than 20% of the meetings), and the recreation therapist (who attended approximately 40% of the meetings). Throughout the duration of the study, only three PIT meetings were cancelled because of poor attendance. These cancellations occurred during the summer months when many members were away on vacation.

Assessment of adherence

The selected mealtime strategies (e.g., care staff sitting down with residents during meals and socializing) and their requisite predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors were reviewed at each of the PIT meetings. When a strategy was not being implemented by the majority of the care staff members, the PIT members would review, in detail, the factors that were either enabling or impeding the strategy from being successfully implemented. For example, during our first PDSA cycle we found that less than 20 per cent of the care staff were sitting down and socializing with the residents during mealtimes. In response to this, the PIT members examined and assessed the predisposing factors (e.g., Do staff know that they are “allowed” to sit down while working? Has this been effectively communicated to all staff, including casual staff members? Do all staff understand why it is important to sit down and socialize with residents during mealtimes?), the enabling factors (e.g., Are there chairs in the dining room for the staff to sit on? Have we reassigned some duties during the mealtimes so that HCAs feel they actually have enough time to sit down and connect with residents during mealtimes?), and the reinforcing factors (e.g., Are staff recognized, appreciated, and celebrated for sitting down and socializing with residents during mealtimes? Are staff reminded via such things as reports, communication books, and posters on the unit that this is a selected strategy to improve our mealtimes for residents?) associated with this strategy. These assessments of the change factors enabled the PIT members to collaboratively identify solutions to address the challenges and then implement the developed solutions via the PDSA cycles.

Review of the detailed records kept during the PIT meetings demonstrated that 88 per cent (n = 15) of the selected mealtime strategies were successfully implemented and sustained for the duration of the study. The only two strategies that were not successfully implemented were both related to the distribution of medications during mealtimes. Despite significant effort, we were not successful in making changes to that care practice in a way that was considered feasible by all staff.

Assessment of responsiveness

Our interview questions focused on the PIT members’ perceptions of the change initiative. When participants described their perceptions of the initiative, two key concepts emerged: (1) personhood enabled as a result of increased communication, and (2) pride in their work as a result of an increased sense of accomplishment. When they were asked what enabled these successful outcomes, two additional concepts emerged: (1) the importance of HCA involvement, and (2) creating time for regular and frequent meetings.

Personhood enabled as a result of increased communication

The participants spoke at length about how this initiative had resulted in increased communication among all stakeholders. They informed us that this increase in communication resulted in increased connection, which in turn resulted in an increased sense of personhood experienced by all participants.

Critically, PIT members noted significant improvement in PCC via greater autonomy and choice for residents, and purposeful relationship building. This was reportedly a result of a “shift in focus” towards acknowledging and embracing the dynamic nature of residents as individuals with unique needs and preferences. Staff members acted on this shift by specifically creating opportunities for residents to make choices with regards to mealtimes.

HCA: The residents love choosing what they are going to drink for dinner and conversations increase as we give them choice.

This also facilitated greater relationship building, as staff took time to discover personal attributes of residents. According to staff, this involved challenging perceptions of the “right” way to behave at work. Specifically, this included disrupting social norms for RCH staff, such as being perceived as “lazy” for sitting and spending time with residents during mealtimes. They now advocated that this care practice was “best practice” and essential for PCC. For example

HCA: I’ve slowed down. I found with [Unit] we were able to connect more with our guys and I learned a lot, of just their histories and things like that and how they are as a person? Are they a joker? Are they serious? I think we’ve gotten a better rapport with them. They’ve gotten to know us a little better too because we’ve allowed them to ask us questions. So, I mean yeah, it’s just opened it up way more, like more personable, more … just, family-like.

Family: The staff sitting and visiting with the residents and getting to know them, and talk to them and find out some of their interests and some of their [life histories] and everything, has really made a difference. Even to find out something as simple as what they would like to drink. They never had that option before…and some of the things that they like to eat, and some of the things they didn’t like to eat and stuff. So that is great, you know, when they visit like that.

These changes led to positive and important outcomes for both staff and residents. For example

HCA: We have had trouble getting one of the residents to sit and eat at meal times, now that we are sitting with the residents, he comes to meals, sits and even feeds himself.

Therefore, for HCAs, being encouraged and enabled to sit down and talk with the residents was especially influential to their ability to offer person-centred mealtimes.

PIT members informed us that, as a result of the increased communication and connection experienced between care staff members, their sense of being a “team” had also improved. For example

Dietary: So we’re not fighting each other, you know, doing opposite things, and we’re all working to the same goal.

HCA: Working within the PIT crew, you kind of learn what’s going on and you can give them extra moral support when they hit a rough patch in life – and it does happen. And vice versa – I mean, it’s brought the team a lot closer together.

Increased communication and connection also occurred between HCAs and management. HCAs informed us that they began to see members of the management team as “people” and felt increased comfort in communicating and collaborating with them. For example,

HCA: I’m old school when it comes to, “my boss is my boss” but now I’m starting to learn that they’re just human beings like me and we can relate a little more.

HCA: I know that before, I was terrified to say even, “good morning” to [Administrator]. He seemed unapproachable, where now if I see [administrator or another member of the management team], I’m automatically saying, “good morning” now. I’m not in knots when they come walking up to me, and that’s the way I felt when [Administrator] was here before the program; it was like, oh my god, what am I in sh** for now. I never suspected it was just a “hello”.

Finally, and significantly, the participants informed us that taking part in the initiative had resulted in increased communication and connection between HCAs and family members. Before the project started, family members were “not allowed” to be in the kitchen or assist other residents (other than their own family member) during mealtimes. Enabling family and staff to work together in creating and implementing person-centred mealtime practices has changed the dynamic of this relationship. Family now feel that they are part of the team. For example

Family: During mealtimes, I felt, well, I wasn’t allowed to do much except with my [own] family, [but] they are all my family, this is their house, this is my family. After I became a member of the [process improvement] team I was able to help everyone, it was really good. I felt like I was doing something worthy and being here and helping.

Dietary: I think the family that were involved see themselves more as partners and … I also think they realise that everybody is trying their best and ‘in the moment’ things happen. So I think they do have a better understanding of what it takes for everything to go smoothly in their home.

Family: I look forward to coming in at lunch now, and I look forward to seeing another member of the PIT team in the [unit].

Family members also became less critical of HCAs and began to focus more on collaborating with them to help them provide better care. For example

Family: So it’s a two-way street; if you want So-and-So to be a better healthcare aide, then you need to see what they need to do that. You can’t demand that they be better, you have to say, “What do you need from me to be better?”

Additionally, for HCAs, the increased connection and communication with family members resulted in an increased opportunity to learn the “little things” that can make a big difference in a person’s life.

HCA: It does help that you do get to know your families and then you get to know more about your resident, through their family, and I think that’s a positive. So yeah, learning little things. I like it. Yeah… we’ve gotten much closer, I think.

Pride in their work as a result of an increased sense of accomplishment

Change is stressful, and most people tend to resist it. However, the PIT members were unanimous in their perceptions that they had enjoyed taking part in the change initiative, were proud of all that they had accomplished, and, if given an opportunity, they would want to do it again. For example

HCA: I just loved being a part of it and, I mean, it’s made me grow more as an HCA—learning, giving that little bit extra, and the way we changed some things around, it’s just awesome. I think it’s great.

Dietary: I really enjoyed it. I liked that we’ve had such a good positive impact for our residents. That’s important to me.

Many of the HCAs also indicated that being a part of this initiative helped to rejuvenate them in their work and resulted in their wanting to be proactive in making other changes in their workplaces. For example

HCA: In 23 years I’ve never been involved in anything like this and it’s opened up my eyes a lot… now I want to learn more. I want to do more and that’s just amazing. It’s given me a new zest for my job!

This “zest” and increased level of engagement by the HCAs was also noted by the administrator. For example

Admin: I’ve seen them [HCAs] disengaged in the past with things, so it’s nice to see them coming together and working as a team on something that benefits our residents, even though it may have seemed like extra work for them, or a change in how they perform their work. Once they could see the benefits from that, I think they were really on board.

PIT members indicated that this pride and sense of accomplishment also seemed to make a positive impact on the care staffs’ overall quality of work-life. For example

Dietary: I think everybody went well above what we expected. I remember the first meeting, being very overwhelmed with all the stuff we were writing down and thinking, “Oh, this is going to be insurmountable. We’re never going to be able to accomplish all this”, and it was so amazing how quickly … it was just, like … they were just doing it and it was great! And now, to come to work and be that happy and so seemingly relaxed and having a good time and still getting the work done!

When asked what had enabled the successful outcomes of this change initiative, the participants all asserted that it was the level of engagement of everyone involved. It was evident to us that the PIT members had decided unequivocally that this was “their project”, and they were determined to see it succeed. The administrator of the RCH reiterated this.

Admin: It’s had a positive impact on the residents and the staff, and I think what made it successful was that the healthcare aides involved really kind of owned it and ran with it [my own italics]. And you’ll get so much more buy-in than if it’s coming from top-down.

In addition to the level of engagement, the PIT members also all indicated that the weekly meetings were critical to the success of the initiative. These meetings provided the PIT members with essential opportunities to engage in increased communication, problem solving, continued learning, and solution seeking. For example

Family: Yeah, I really like the weekly meetings, it just kept everybody together and on the same page, and if there were problems or something that had been happening, it could be brought out at the meeting and then it was being dealt with.

Dietary: So it’s really good for us to be able to have that communication with the [HCAs] and it’s helped even outside the project for so many other things. Like when we’ve had issues with staffing or questions about food services, it’s opened that line of communication so much better. So now, if you have any problems come … you know, just give me a call and we’ll work it through and figure it out.

Finally, when asked what they felt would help to ensure that the outcomes from the change initiative would be sustained, the participants informed us that, in addition to continuing the PIT meetings, having management that was supportive and engaged was essential to the sustainability of the increased person-centred mealtime practices. For example

Dietary: I think management has to make it a priority and make it important to them.

HCA: I liked our meetings. It kept us on track and, yeah, I think we should continue with our meetings. Then we can work through all the concerns and challenges and questions that come up and make it work, like even better. Yeah, definitely stick to the meetings.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study offers evidence that practice change initiatives that focus on stakeholder engagement can provide a promising method for improving the provision of person-centred mealtime practices at RCHs. It is important to note that administration turnover and lack of administrative support have been repeatedly cited as barriers to culture change in the long-term care sector (Engle et al., Reference Engle, Tyler, Gormley, Afable, Curyto and Adjognon2017). Therefore, it is especially significant that this practice change initiative was successful, despite leadership turnover. Our findings demonstrate that person-centred change initiatives at RCHs should incorporate individuals at all levels of care, and need to take into consideration the socio-structural components of the care environment.

Our study also elucidates the importance of cultivating an empowered workforce by implementing practices that enable and encourage collaborative decision making and increase care staffs’ autonomy and self-determination. We found this to be essential to the outcomes that occurred as a result of the change initiative. These findings are consistent with those of Caspar and O’Rourke (Reference Caspar and O’Rourke2008), who demonstrated that care staffs’ level of empowerment was directly associated with their perceived ability to provide PCC. It also reinforced the finding that staff who are “empowered, willing, and trained" (p. S22) are more likely to respond to resident choices in mealtime practices (Elliot et al., Reference Elliot, Cohen, Reed, Nolet and Zimmerman2014).

It is noteworthy that a short (20 minute), yet consistently scheduled and well-facilitated weekly meeting was both essential and effective in producing the outcomes that we observed during this study. Given the number of positive changes that occurred (and were sustained) during the course of this study, it is reasonable to assert that this meeting plan provided an effective and efficient use of time and resources. It is important to note, however, that the PI facilitated these meetings using the skills and principles from the responsive leadership intervention developed by Caspar, Le, and McGilton (Reference Caspar, Le and McGilton2017b). The significance of this should not be underestimated, because the presence of leaders and managers who embrace a leadership style of “supporting and valuing staff” combined with being “responsive to staff needs” and offering “solution-focused approaches” to care decisions have been found to be essential to successful practice change initiatives (Caspar et al., Reference Caspar, Le and McGilton2017b; Kirkley et al., Reference Kirkley, Bamford, Poole, Arksey, Hughes and Bond2011; McGilton, Reference McGilton2010; Sjogren, Lindkvist, Sandman, Zingmark, & Edvardsson, Reference Sjogren, Lindkvist, Sandman, Zingmark and Edvardsson2017)

Finally, we found that the quality of communication and the level of effective, supportive teamwork were both inextricably intertwined. These organizational factors were also especially salient in their ability to influence the extent to which PCC principles were enacted in practice. When reviewing the literature, it is clear that the development of effective, supportive, and trusting teams (e.g., social support from colleagues and leaders, effective and open communication, a shared vision of care philosophy) is essential to any change initiative aimed at increasing the provision of PCC (Brooker & Woolley, Reference Brooker and Woolley2007; Caspar, Reference Caspar2014; Leutz, Bishop, & Dodson, Reference Leutz, Bishop and Dodson2010; Sjogren et al., Reference Sjogren, Lindkvist, Sandman, Zingmark and Edvardsson2017; Vikstrom et al., Reference Vikstrom, Sandman, Stenwall, Bostrom, Saarnio and Kindblom2015).

Some limitations of the study should be noted. First, the sample size was small, as this study was only conducted on one unit at one RCH. In anticipation of this, we used repeated measures to further enhance the validity of the conclusions. Repeated measures help to control for factors that cause variability among the subjects. This approach allows one to track change over different intervals of time – 1, 3, and 6 months post-intervention – which enhances validity. Second, we did not include actual resident health outcomes or their perceptions regarding quality of care (Edvardsson & Innes, Reference Edvardsson and Innes2010), as this was beyond the scope of our study. Third, because the PIT meetings were PI led, the intervention would not be able to be completely replicated in the “real world”. Therefore, further studies, within which the PIT meetings are facilitated by PIT members, are needed. Despite these limitations, this study’s promising results indicate that the stakeholder engagement focused practice change initiative is a feasible method for improving PCC mealtime practices in RCHs. It also adds to the body of knowledge suggesting that improved engagement, teamwork, and collaboration are directly related to the quality of care provided in health care settings. Future endeavours aimed at improving quality of life and care in continuing care settings are therefore encouraged to incorporate principles and processes that support and enable engagement among all stakeholders of the health care team.

Appendix 1: Feasible and Sustainable Culture Change Intervention (FASCCI) model implementation steps