Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is regarded as a controversial treatment by many people (United Kingdom Advocacy Network, 1995; Reference PedlerPedler, 2000). In England and Wales, special safeguards exist under common law for patients voluntarily undergoing this therapy and under both current and proposed legislation for those receiving compulsory treatment. Where consent is given, the consent procedure and the consent itself must be fully documented. Consent to treatment is valid only when the patient has been adequately informed of risks and benefits and freely chooses to undergo treatment. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence in England has recently recommended improvements to the procedures for consent to ECT (NICE, 2003). In this paper we review studies in which patients’ retrospective views of informed consent to ECT have been investigated and use quantitative and qualitative analyses to consider whether there are sufficient safeguards in place in relation to this treatment.

METHOD

Identification of research studies

The academic literature was searched to identify peer-reviewed studies that ascertained patients’ views about ECT. The search terms and exclusion criteria have been described by Rose et al (Reference Rose, Wykes and Leese2003). Of the 26 studies conducted by clinicians that were identified, 13 dealt with issues of information and consent.

A Reference Group made up of recipients of ECT and of qualitative researchers enabled us to identify from the ‘grey’ literature nine research reports written either by patients or in collaboration with them. Four of these dealt with issues of information and consent. The Communicate study (Reference Philpot, Collins and TrivediPhilpot et al, 2004) had not been published when we conducted this review, but we had access to the raw data.

Identification of material for qualitative analyses

Individual patient reports of ECT, which we refer to as ‘testimonies’, were defined as an individual speaking or writing about first-hand experience of ECT. Accounts of the experiences of others, offers of advice or support and campaigning materials were excluded.

Testimonies were sought purposively, which means that sources were identified from a diverse range of contexts. Five sources of material were included. First, on 13 June 2001 all e-mail forum material from the websites ect.org (http://www.ect.org) and HealthyPlace.com (http://www.healthyplace.com) was downloaded, producing 81 messages organised in related ‘threads’. The first of these websites has a more negative attitude towards ECT than the other, which is comparatively neutral. Second, a general internet search produced a further 15 testimonies. The British Library oral history video archive, known as the Testimony Archive, contains 50 interviews of which 23 mentioned ECT. Each interviewee was a person who had been in a long-stay psychiatric hospital. The Proquest newspaper database was searched to produce 6 testimonies. Finally, consumer newsletters, books and magazines known to the Reference Group were hand-searched, producing 10 testimonies.

Analysis

Research studies and reports

A descriptive systematic review was carried out. Data were extracted from the research studies to answer the following questions:

-

(a) What proportion of people undergoing ECT felt they had adequate information about the procedure?

-

(b) What proportion had ‘objective knowledge’ of the procedure? (Objective knowledge was defined as knowing that the treatment involves anaesthesia, an electric current is passed through the head and a convulsion or ‘fit’ is induced.)

-

(c) What proportion felt they had enough information about possible side-effects?

-

(d) What proportion perceived that they had been coerced to have ECT?

Perceived coercion is defined here as having signed a consent form but still feeling that there was pressure to have the treatment. We also touch on legal compulsion, although most papers explicitly excluded patients given ECT under formal provisions.

Scatter plots against date of publication were constructed for information and perceived coercion to see if there were trends over time.

Testimony

Testimony data were analysed qualitatively. The main method was content analysis (Reference BauerBauer, 2000), which incorporates frequency counts and so allows for an assessment of the importance of specific themes in the data. The results of the qualitative analysis are quotations. These were selected according to two criteria. First, the theme appeared frequently. Second, it gave detail and depth to the systematic review.

RESULTS

Of the 17 papers and reports that included questions on information and/or consent, 4 contained data that could not be used for the descriptive systematic review. Goodman et al (Reference Goodman, Krahn and Smith1999) included a question about information in their schedule but did not give any results for this question. Hillard & Folger (Reference Hillard and Folger1977), Calev et al (Reference Calev, Kochav-Lev and Tubi1991) and Battersby et al (Reference Battersby, Ben-Tovim and Eden1993) reported group differences in information about ECT but not raw data.

Information

The most frequently asked question in the research studies was whether respondents felt they had been given sufficient information about ECT. Eight clinical studies asked in a post-treatment interview whether information prior to treatment was adequate. All but one appears to have used terms such as ‘adequate information’ or ‘adequate explanation’. In the study by Kerr et al (Reference Kerr, McGrath and O'Kearney1982), respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the statement, ‘patients are never told what is going on’.

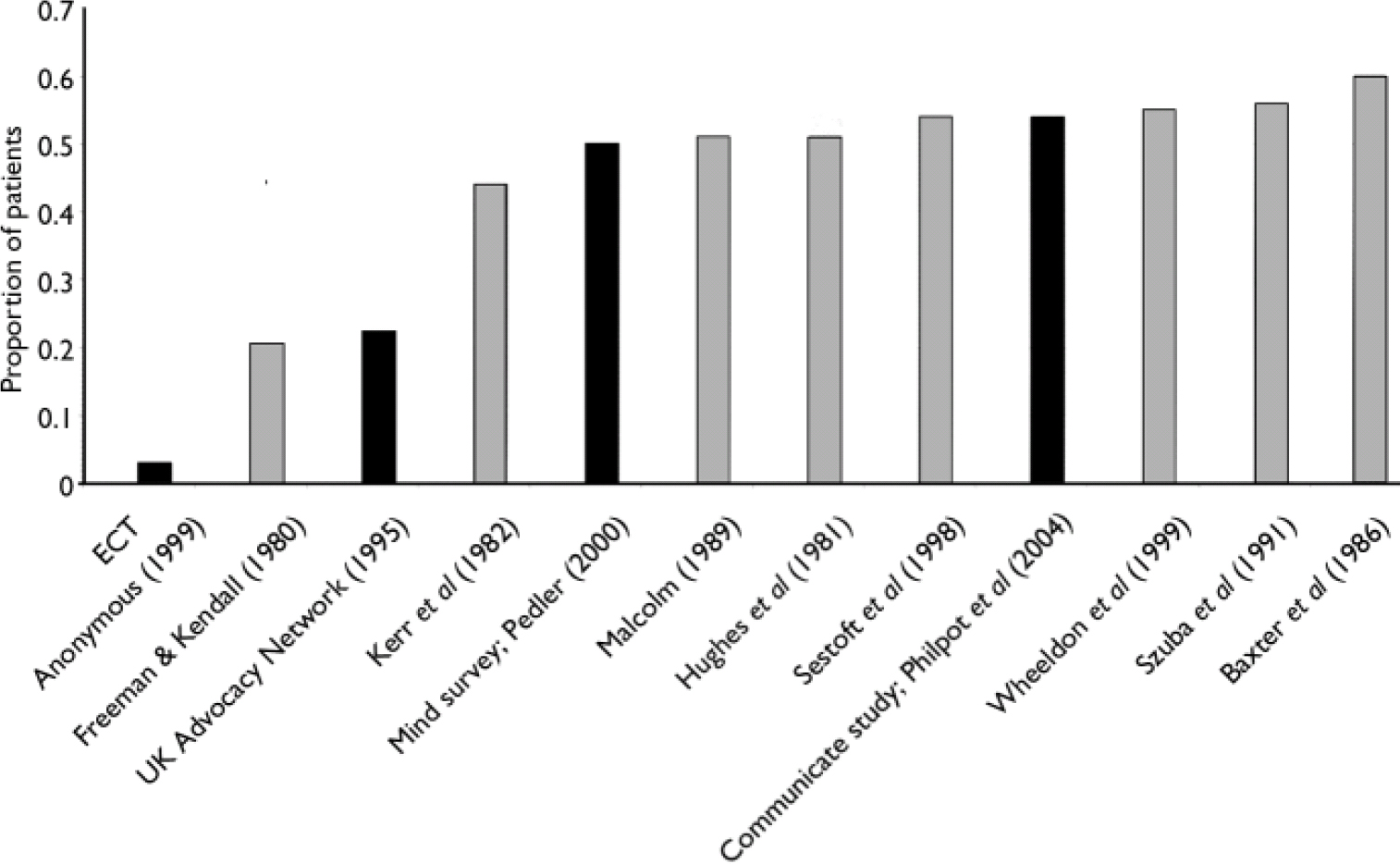

Four consumer-led or collaborative surveys asked questions about information. The United Kingdom Advocacy Network (1995) and Communicate (Reference Philpot, Collins and TrivediPhilpot et al, 2004) questions mirror those in the clinical research. The Mind survey questions (Reference PedlerPedler, 2000) were very detailed and the one used here is whether respondents were told why they were being given the treatment. The ECT Anonymous (1999) question specifically mentioned explanation of the risks of ECT. Disregarding these slight differences, Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents who said they were given sufficient information about ECT in each of the 12 studies.

Fig. 1 Proportion of patients who felt that they had received sufficient information about electroconvulsive therapy (solid bars indicate patient-led or collaborative study).

Although the questions asked were not always directly comparable, 9 of the 12 studies give a consistent picture. About half (45–55%) of respondents reported that they were given an adequate explanation of ECT, implying a similar percentage felt they were not. Of these 9 studies, 2 involved collaboration with patients – the Mind and Communicate studies – so there is no apparent polarisation between clinical and patient-led research on the question of information. The scatter plot showed no trend over time in the proportion who thought they had adequate information.

Objective knowledge

Four studies assessed patients’ ‘objective knowledge’ concerning ECT, as defined in the Method section. All the researchers were clinicians and all studies were carried out in the UK.

The proportions of respondents in these studies who had basic knowledge of ECT is low (Table 1). The authors quote patients making remarks such as ‘I should think not!’ or ‘The doctor wouldn't allow that’ when asked if they knew a convulsion was involved.

Table 1 Objective knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy among patients who had undergone the procedure in four UK studies

| Study | Patients with full knowledge (%) |

|---|---|

| Hughes et al (Reference Hughes, Barraclough and Reeve1981) | 7 |

| Benbow (Reference Benbow1988) | 12 |

| Riordan et al (Reference Riordan, Barron and Bowden1993) | 12 |

| Malcolm (Reference Malcolm1989) | 16 |

Patient-led research and testimony

The Mind study asked extremely detailed questions about information (Reference PedlerPedler, 2000). The following quotation is typical:

‘I felt under a lot of pressure from the staff to go ahead with ECT. I personally don't remember receiving information about how it would work, side-effects, etc.’ (woman, ECT within 6 months of study).

In the testimony data, there are also examples of complaints about insufficient information that begin to hint at a relationship between lack of information and a sense of helplessness.

‘We need full information – not the bland assurances of those who prescribe or the blanket condemnation of those who object to their prescription’ (woman, three courses of ECT; anonymous testimony, further information available from the authors on request).

‘I didn't even know what the letters ECT stood for. I didn't know and it wasn't explained to me that I would have electrodes attached to my head and that they would put an electric current through my brain (woman, 12 ECTs in 1990; anonymous testimony, further information available from the authors on request).

Information about side-effects

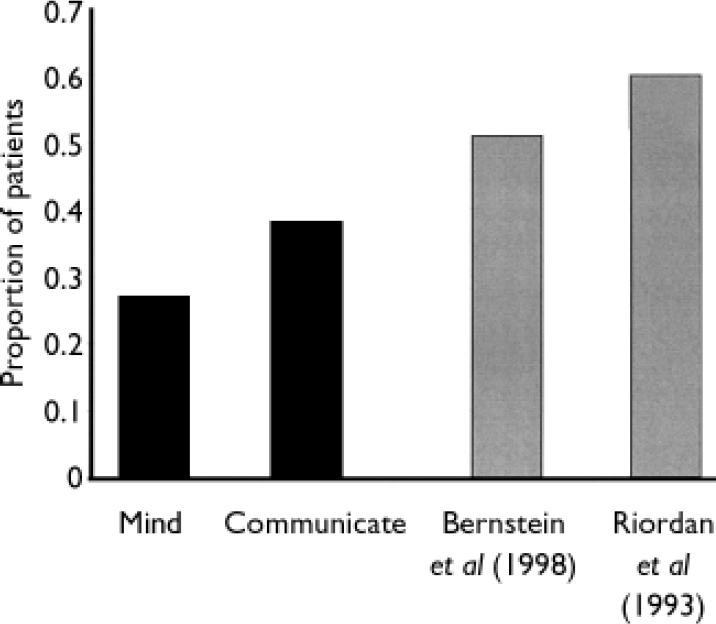

Four studies asked their respondents whether they had been given sufficient information about side-effects (Fig. 2). Two were collaborative studies (Reference PedlerPedler, 2000; Reference Philpot, Collins and TrivediPhilpot et al, 2004) and two were clinical ones (Reference Riordan, Barron and BowdenRiordan et al, 1993; Reference Bernstein, Beale and KellnerBernstein et al, 1998). A respondent to the Mind survey put it like this:

Fig. 2 Proportion of patients who felt they had sufficient explanation about side-effects (solid bars indicate patient-led or collaborative study).

‘Possible side-effects were downplayed and only lightly touched upon’ (man, ECT within 2 years of date of study).

Over half of the more spontaneous comments about inadequate information were specifically linked to the possible side-effect of long-term memory loss.

Consent

Legal compulsion

Only two studies, both conducted in the UK, included patients who had been treated under formal powers; this is a limitation of the data. Wheeldon et al (Reference Wheeldon, Robertson and Eagles1999) reported that although patients who received compulsory treatment were in retrospect satisfied with ECT, they were unsure about information provision procedures. Malcolm (Reference Malcolm1989) reported that formally treated patients were less knowledgeable about ECT than those receiving informal treatment. However, they were more likely to be dissatisfied with information provision.

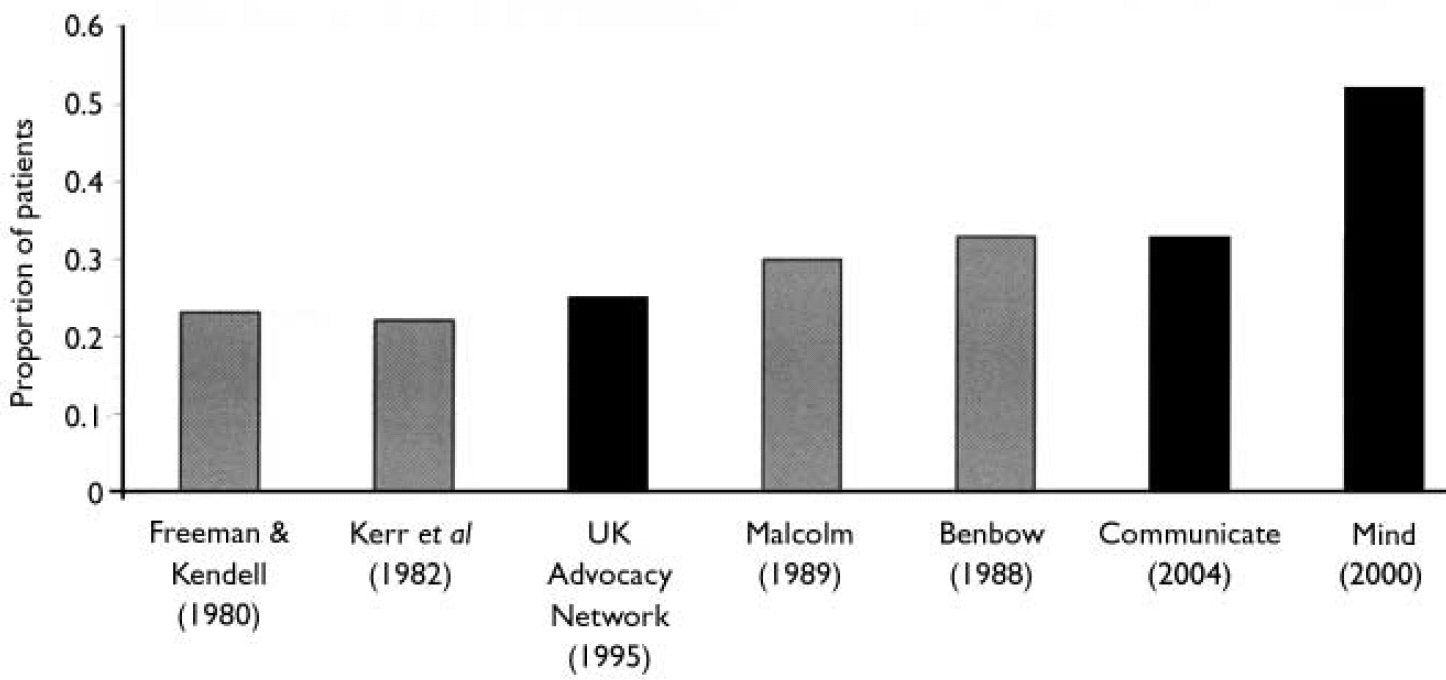

Psychological or perceived coercion

Patients may feel they did not make a free choice to have ECT even when they apparently consented and even when not legally compelled. The safeguard here is that consent must be documented, and good practice is that a specific consent form must be signed. The proportion of patients who gave their formal consent, but felt they had no choice, was therefore ascertained for each of the seven papers or reports that asked about this. The relevant questions are whether the person knew that treatment could be refused or felt pressured to have the treatment. The statement that Kerr et al (Reference Kerr, McGrath and O'Kearney1982) put to people in their survey was, ‘ECT is given if patients don't behave’, and they were asked to agree or disagree with this. The UK Advocacy Network asked their respondents if ECT had ever been used as a threat. These two questions are more strongly worded than the others. Some of the variability shown in Fig. 3 is a consequence of the different questions asked. However, the results do not polarise according to a clinical v. patient survey division. The Mind results show a significantly higher proportion of patients who felt they had no choice, but their questionnaire was very detailed on this issue. The scatter plot indicated that the proportion of people who feel coerced has increased with time.

Fig. 3 Proportion of patients consenting to therapy who felt they had no choice (solid bars indicate patient-led or collaborative study).

Testimony and perceived coercion

When the issue of consent is mentioned in testimonies it is usually to explain why the person did not feel that he or she had freely given informed consent. The following statement was made by a respondent to the Mind survey:

‘I was given no information and had to sign for it after all my medication at night so I was very drugged when I signed the form for my consent’ (woman, ECT within 3 years of date of study).

This is not a bland account of signing or not signing a form. In the UK particularly, users speak of the threat of compulsion:

‘I want you to have ECT. You're not sectioned at the moment, but I will section you, under section 3 of the Mental Health Act, I will get a second opinion doctor to come and... assess you’ (woman, nine ECTs in 1993 or 1994; British Library Testimony Archive).

The power of the professionals prescribing the treatment is revealed in the testimonies, as is the parallel sense of helplessness on the part of the patient:

‘I remember being very anxious about these treatments, since I was not told about them, about what was involved. I remember having the feeling of being led to slaughter since it seemed hopeless to stop them – and trusting the doctor as I was very young at the time’ (woman, six to eight treatments in 1971; anonymous testimony, further information available from the authors on request).

DISCUSSION

Approximately half of those who receive ECT feel that they are given insufficient information about the procedure and approximately a third perceive themselves to have been coerced into having the treatment. This finding is consistent across both the clinical and the service user studies, and its meaning to service users is illustrated by the quotations from the testimony data. These data show that perceived coercion in particular elicits strong emotional responses from those undergoing ECT.

The sampling frame for the testimony data was not random but purposive. The testimonies are unlikely to be representative of all recipients of ECT as biases exist in the decision to post a testimony on the internet. However, the purpose of the analysis here is not to represent but to explain and give depth to the findings of quantitative studies. Future research should use qualitative methods with a representative sample of consumers.

Information

Despite the consistency in numerical findings about information prior to ECT, clinical and service user studies evaluate these findings differently. Some clinical researchers argue that many patients do not want information and prefer instead to put their trust in the doctor. Benbow (Reference Benbow1988), in particular, states that perhaps patients should not have information needlessly ‘forced’ on them. Not all the clinical researchers are this sanguine, but most indicate that trusting the decisions of the doctor is either to be welcomed or at least should be a choice. Mind, on the other hand, concludes on the basis of similar numerical results that the situation is unacceptable.

Exceptions to the figure of about 50% were one clinical study (Reference Freeman and KendellFreeman & Kendell, 1980) and two consumer studies (UK Advocacy Network and ECT Anonymous), all of which gave much lower figures. Freeman & Kendell are scrupulous in reporting their results and it is clear that there were six possible responses to the question about information. A fifth of the users (20.6%) said they did have an adequate explanation about ECT; however, only 49% said they had an inadequate one. The remaining consumers gave other response options. Nearly all other studies report results in ‘yes/no/don't know’ form; these studies may therefore be oversimplifying the issue.

A possible explanation of the UK Advocacy Network finding – which is likely to be even more true of the ECT Anonymous survey – is that members of these organisations do not share the trust that clinical studies attribute to their respondents. However it is also possible that these people had more knowledge about ECT than other groups and so had a different standard against which to assess the information they were given. These organisations provide their memberships with a great deal of information about ECT, some of which would be considered misinformation by many clinicians.

In light of the findings in Table 1, what looks like an absurd figure from ECT Anonymous regarding information about the treatment becomes more comprehensible. The vast majority of patients, at least in the UK, do not know what the treatment involves and so it might not have been explained to them adequately. Patients who know exactly what the treatment involves are not typical. If the explanation they were given at the time of treatment was a typical one, most in retrospect would regard it as inadequate.

There is, however, one problem with the perceived lack of information on the part of service users: ECT is acknowledged to cause short-term memory loss, and so people may well forget some of what is told to them. The high proportion of people in this review who felt misinformed makes it unlikely that this accounts for all cases. However, techniques to improve the retention of information, such as repeating it before each treatment and the use of video and flashcards, might lead to improvements.

Information concerning side-effects

The two studies in which patients collaborated (Mind and Communicate) give lower figures for sufficient information about side-effects than the two clinical studies. This is the only research item for which there is polarisation between the collaborative and clinical studies. The Mind survey asked very detailed questions on information and this might have created an alertness or ‘response tendency’ on the part of respondents.

Informed consent and other treatments

It may be that problems with informed consent also occur with other treatments, both in psychiatry and in general medicine. A literature search with the terms ‘informed consent’ and various psychiatric and medical treatments revealed no comparable body of literature to that reported here. The exception is informed consent in relation to trials (Reference MorenoMoreno, 2003), but this is different to the situation with ECT.

In psychiatry, Brown et al (Reference Brown, Billcliff and McCabe2001) investigated informed consent to psychopharmacological treatments among long-stay psychiatric in-patients. They discovered a lack of knowledge about medications and the reasons for giving them. Eighty-two per cent of their respondents did not know they could refuse their medicines. These patients were nevertheless happy with the situation, whereas many of the ECT respondents were not. More detailed work is needed to analyse studies on informed consent for other psychiatric treatments and across medical specialties.

Legal compulsion

Under proposed mental health legislation, the safeguard for those compelled to have ECT will rest with mental health tribunals rather than, as now, with a second opinion. The Department of Health for England and Wales rejected the Richardson Committee's recommendation that compulsory treatment should be based on the principle of lack of capacity (Department of Health, 1999, 2002). Wheeldon et al (Reference Wheeldon, Robertson and Eagles1999) noted that all their formally treated service users were deemed to have capacity; in the study by Malcolm (Reference Malcolm1989) most were also, the others being treated under emergency powers. Although only two papers considered legal compulsion, the data we do have suggest that patients treated under compulsion are more dissatisfied with the explanation they were given but are slightly less knowledgeable about the procedure.

Perceived coercion

There is growing interest in the phenomenon of perceived coercion. It has been argued that legal compulsion is not the only kind of coercion that recipients of mental health services experience and that perceived coercion is equally significant. Monahan et al (Reference Monahan, Hodge and Lidz1995) demonstrated that there is no one-to-one correspondence between being compelled and feeling compelled. The MacArthur Admissions Experience Interview (Reference Lidz, Hodge and GardnerLidz et al, 1995) focuses on coercion and pressures in relation to admission and has a four-item sub-scale on perceived coercion. Most of the questions put to users in the current review are consistent with this sub-scale.

Electroconvulsive therapy has special status under English law as the procedure of obtaining informed consent must be recorded, and it is good practice for the patient to sign a specific consent form. However, it is widely reported in the clinical as well as in the service user literature that even when patients are not given ECT under compulsion, they often feel that they did not freely give their consent. Malcolm wrote that many patients ‘commented that it was futile to refuse as they would end up getting treatment anyway’ (Reference MalcolmMalcolm, 1989: p. 163).

As with the provision of information, some clinical researchers conclude from their findings that many patients are happy to let the doctor decide what is best for them when it comes to the decision to have ECT. We saw an example of this in the last quote in the Results section, the person attributing her trust to her youth. Benbow concludes:

‘We have a duty to make effective treatments available to patients, and we should not deprive them because of proscriptive legal requirements for consent to treatment that belittle the trust between the patient and his or her medical advisor’ (Reference BenbowBenbow, 1988: p. 152).

It has been demonstrated that this trust in doctors is not shared by many of those who responded to the patient-led surveys. The testimony data also reveal feelings of distrust. This may be illuminated by the qualitative work of Johnstone (Reference Johnstone1999). She specifically recruited participants who felt they had been damaged by ECT, and this is also true of the study by Freeman et al (Reference Freeman, Weeks and Kendell1980). Of the 20 people she interviewed, 14 had signed a consent form. When probed on this, some said they were so desperate they would have tried anything. However, many expressed a sense of powerlessness when faced by a medical professional so confident in the proposed treatment. It is clearly different to put one's faith in a doctor from a positive sense of trust than to do so from a sense of powerlessness. The balance of these perspectives among recipients of ECT must remain an open question and is a topic for future research.

If the documenting of informed consent is designed to act as a safeguard for a controversial treatment such as ECT, it clearly fails in a significant proportion of cases. To invoke trust in the doctor is not a good enough reason to fail to be scrupulous about informed consent. Where such trust exists, it can only be strengthened by detailed information. Where it does not, the withholding of information and pressure to consent cannot build it.

Has ECT practice improved over time?

As a result of initiatives such as those conducted by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Reference Duffett and LelliottDuffett & Lelliott, 1998), it is often said that ECT practice today is much better than it was even 20 years ago. However, on the specific issue of informed consent, our analyses do not bear this out. There was no relationship between the date of the study and the adequacy of information as judged by the people who were given ECT. The proportion who feel they did not freely choose the treatment has actually increased over time. Additionally, the testimony quotations in this paper come from different points in time and demonstrate that the same themes arise whether the patient had received treatment a year ago or 30 years ago. Perhaps the new ECT Accreditation Scheme from the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Research Unit will improve the situation.

In summary, the material and analyses presented here suggest that current legal frameworks fail to ensure that a majority of recipients of ECT, voluntary or involuntary, feel that information and consent procedures are adequate. Proposals for reform of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales are unlikely to address these concerns.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Users should repeatedly be given full information about electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as a procedure, until adequate comprehension has been achieved.

-

▪ Users should be given full information about potential benefits and side-effects, including memory loss.

-

▪ Professionals should ensure that no one signs the consent form for ECT under duress.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Few of the papers studied included people treated under legal compulsion.

-

▪ More work is needed comparing informed consent to ECT with informed consent to other treatments.

-

▪ Questions in the surveys studied were not all directly comparable.

Acknowledgement

The research was funded by a grant from the Department of Health.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.