9.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we analyse the EU governance of water services and its discontents. We investigate the extent to which EU leaders called for a commodification of water through EU laws and new economic governance (NEG) prescriptions; and we assess the transnational countermovements of unions and social movements that they triggered. In addition, we assess the interactions of these vertical EU governance interventions with horizontal market pressures triggered by the making of a European market in the sector.

In the water sector, horizontal market integration has been advancing relatively slowly because of significant physical barriers to trade. As opposed to other public network industries (including transport), water supply and distribution systems are typically contained within sub-national borders. The distribution of water (except bottled water) remains a local issue, making tap water a non-tradable good. Nonetheless, water services were hardly insulated from neoliberal demands to commodify public services across the globe (Dobner, Reference Dobner2010; Bieler, Reference Bieler2021; Moore, Reference Moore2023). From the 1980s onwards, water-related technologies, governance ideas, and, most importantly, capital have become ever more transnational. Water services became a target of mobile capital across borders. The operation of water supply networks and participation in water-related infrastructure projects (the improvement of sanitation systems, for example) represented lucrative business opportunities for transnational corporations (TNCs), especially given the scale and know-how requirements of these tasks (Hall and Lobina, Reference Hall and Lobina2007: 65). The expansion of water TNCs, however, has also triggered the emergence of countervailing protest movements defending the commons, especially in countries where the arrival of TNCs meant direct privatisation and price increases (Sultana and Loftus, Reference Sultana and Loftus2012; Bieler and Erne, Reference Bieler and Erne2014; Bieler, Reference Bieler2021).

Whereas horizontal (market) integration processes are relatively uniform in their commodifying impact, vertical (political) EU interventions can go in two opposite directions: they can either decommodify water services through setting EU-wide environmental and quality standards or commodify them through EU laws and governance prescriptions that curtail public spending and marketise the sector. In this chapter, we analyse the EU governance of the water sector throughout two time periods. Section 9.2 outlines the developments before the 2008 crisis, focusing on the EU’s ordinary policymaking procedures through EU laws and court rulings. In section 9.3, we analyse the policy orientation of the EU’s country-specific NEG prescriptions for Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania, which the European Commission and Council of finance ministers (EU executives) began issuing after 2009 (see Chapters 2, 4, and 5). Water services is an area where EU-level commodification through EU laws and court rulings had advanced moderately before 2008. The EU’s shift to NEG after the financial crisis therefore opened up opportunities for further water service commodification, as shown in section 9.3. Section 9.4 outlines and assesses the counterreactions triggered by vertical EU interventions in the water sector, most importantly, the first successful European citizens’ initiative (ECI) on the Right2Water. In the conclusion, we discuss the links between different modes of integration, commodification, and countervailing mobilisations by unions and social movements in the water sector.

9.2 EU Governance of Water Services before the Shift to NEG

In most EU member states, water provision is the task of local authorities that operate under a national regulatory framework. EU governance has nevertheless made significant inroads in the area in recent decades. A significant part of the EU’s acquis communautaire deals with water services from an environmental perspective, but the economic aspects of water management have also gained an increasingly European dimension. We use the distinction between environmental and economic management for analytical purposes but, as we shall see, the environmental governance of water has also substantial economic implications, in terms of whether the legislation prescribes market or non-market solutions as the most appropriate way to ensure the sustainability and quality of water resources.

Phase One: Preventing Regime Competition on Water Quality

Community legislation targeting the water sector started to appear in the 1970s, with specific directives on quality standards (Directive 75/440/EEC, Directive 79/869/EEC). Taking a more comprehensive approach, in 1980 the Council adopted Directive 80/778/EEC on the quality of water intended for human consumption, commonly known as the Drinking Water Directive (DWD). As their basis, the directives invoked Art. 2 of the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC Treaty), which outlined the Community’s central aims.Footnote 1 These directives stated that the approximation of laws across member states was needed, as the differences in national legislation might create differences in the ‘conditions of competition and, as a result, directly affect the operation of the common market’ (Directive 80/778/EEC, Preamble). The directives aimed to tackle the disparities in quality standards across member states, which could have been exploited as unfair competitive advantage. Despite the directives’ semantic links to the common market project, they pointed in a decommodifying policy direction, as they took water quality out of regulatory competition.

The DWD was first updated in 1998, catching up with some of the new developments in the sector since 1980, including quality standards for bottled water. Nevertheless, some of the more ambitious quality goals, such as odour, taste, or colour, were dropped from the final text of the directive because of objections by water suppliers. For these reasons, the cost implications of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) were relatively modest and were spread out over a long timeframe (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lanz, Lobina and de la Motte2004: 11–12).

Phase Two: Towards the Commodification of Public Water Services

By contrast to the DWD case discussed above, the implementation of the Urban Waste-Water Treatment Directive (91/271/EEC) entailed much higher costs, transforming the financing models of water investment and also strengthening the position of the private sector. The infrastructural developments needed to comply with the waste-water directive amounted to ‘arguably the largest common infrastructure project undertaken by the EU in its history’ (Hall and Lobina, Reference Hall and Lobina2007: 65). This strained the budgets of municipalities and national governments that were under pressure to fulfil the Maastricht deficit and debt targets in the run-up to the introduction of the Euro (see Chapter 7). Implementing the directive was also challenging financially in Central and Eastern European countries that joined the EU in the 2000s. Subsequently, a large share of European regional and cohesion funds was used to meet this challenge. Overall, the financing needs of waste-water investment combined with EU-wide austerity contributed to strengthening the role of water TNCs, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, including one of our country cases, Romania (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lanz, Lobina and de la Motte2004: 13; Hall and Lobina, Reference Hall and Lobina2007: 66). Private companies usually undertook these projects in public–private partnership (PPP) and concessions arrangements (Ménard, Reference Ménard, Ménard and Ghertman2009).

EU-level legislation in water services obtained a much more explicit legal base with the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992. Art. 130s TEC (now Art. 192 TFEU) established the EU’s competence for setting environmental standards in the area, thereby enabling EU legislators to adopt EU laws concerning the management of water resources. Building on these new powers, in 2000 the EU adopted the WFD as the main and most comprehensive piece of European legislation in water services. The directive has the ambition to cover all relevant aspects of water management in Europe, the protection of drinking water being only one objective. Unlike the DWD or the Waste-Water Treatment Directive, the WFD contains few direct technical targets but operates at a more general level, setting guidelines and principles for a variety of connected stakeholders.

The WFD embodies the contradictions of the Europeanisation of the water sector. The preamble to the directive declares that water ‘is not a commercial product like any other but, rather, a heritage which must be protected, defended and treated as such’ (Directive 2000/60/EC, Recital 1). The above decommodification principle stands in contradiction to the directive’s embrace of the idea that market mechanisms, in particular pricing, can be used effectively to achieve the goal of sustainable water management. The WFD is couched in market-based terminology, such as supply and demand, and requires member states to prepare economic analyses of water use in their areas.

A significant element of the directive is the cost recovery principle, which demands an adequate financial contribution from water users and polluters to cover the costs of the environmental protection of water. Art. 9 of the directive (titled Recovery of costs for water services) prescribes that ‘Member States shall ensure by 2010 that water-pricing policies provide adequate incentives for users to use water resources efficiently, and thereby contribute to the environmental objectives of this Directive’ (Directive 2000/60/EC, Art. 9). Art. 9 also includes a derogation from the adequate water-pricing principle on the basis of ‘established practices’ that allowed Ireland to continue financing water services from general taxation.

To sum up, our review of the relevant documents suggests that EU environmental legislation in the field of water management has assumed an increasingly commodifying character over time, even though this happened gradually and has not flipped the balance of policymaking, which is still dominated overall by ideas of regulating rather than expanding the market. Two mechanisms propelled the limited commodification of environmental rules.

First, private actors dominated the infrastructural investment projects needed to achieve the standards set out in the Waste-Water Treatment Directive. Second, the WFD introduced an overarching theme into water-related EU legislation that considers the market mechanism as an effective way of solving environmental problems. Even though this formulation is vague in the text of the directive, the Commission and the European Environment Agency recurrently interpreted the provision in their communications and reports in a commodifying way, for example by emphasising the responsibility of individual households to protect water resources by paying the market price for drinking water (Page and Kaika, Reference Page and Kaika2003: 339–340; Kirhensteine et al., Reference Kirhensteine, Clarke, Oosterhuis and Munk Sorensen2010; European Commission, 2012; European Environment Agency, 2013).

Phase Three: Frontal but Unsuccessful Attempts to Commodify Water

The shift towards more commodification in environmental legislation in the early 2000s was matched by the first direct attempts in European economic governance to liberalise water provision. Until in the 2000s, sector-specific liberalising directives did not target drinking water and sanitation services, although other network industries (such as electricity, gas, transport, and telecommunication) were made part of the EU internal market (see Chapters 7 and 8; Bieling and Deckwirth, Reference Bieling and Deckwirth2008: 242; Crespy, Reference Crespy2016: 43).

With the appointment of the neoliberal Dutchman Frits Bolkestein as Commissioner for Internal Market and Taxation in 1999, pro-commodification actors started to show more interest in the water sector. Bolkestein championed an outspoken, radical, and comprehensive agenda of service liberalisation, stating explicitly that such an agenda should include water. This view on water is documented not only in the Commissioner’s speeches but also in Commission-sponsored policy studies and a Commission communication (Bolkestein, Reference Bolkestein2002; Gordon-Walker and Marr, Reference Gordon-Walker and Marr2002; European Commission, 2003).

Bolkestein advocated the commodification of the water sector as ‘a practical instrument for establishing the correct relationship between price, quality and the standard of the service provided’ (Bolkestein, Reference Bolkestein2002: 6). Following up on this, the Commission’s Communication on Internal Market Strategy Priorities 2003–2006 stated that the Commission would launch a comprehensive review of the sector and consider ‘all options’, including legislative proposals in the area of competition law, while respecting neutrality of ownership and public service obligations (European Commission, 2003: 13–14).

Despite the radically pro-commodification attitude of the Commissioner and the ambitious tone in the reviewed policy documents, the text of the directive proposed by the Commission on the Services in the Internal Market eventually treated the water sector as an exception. The Commission’s proposal, published in March 2004, allowed for derogations for non-economic services of general interest (including water) from the country-of-origin principle, the most controversial part of the directive (see Chapter 7). The scope of the Services Directive in its final form (2006/123/EC) is even more restrictive, excluding not only ‘water distribution’ but also ‘water distribution and supply services and wastewater services’. EU legislators finally excluded water services from the final directive as a result of transnational protests in favour of people’s access to water as a human right – a claim that found support in the European Parliament and among central member state governments (Crespy, Reference Crespy2016). We discuss the development of vital countermovements in more detail in section 9.4.

9.3 EU Governance of Water Services after the Shift to NEG

In section 9.2, we have shown that the exclusion of water services from the EU Services Directive prevented an EU-wide commodification of the water sector, even though amendments to the EU directives on drinking water and waste-water gradually introduced new provisions in favour of user charges and an increasing involvement of private capital in the sector. In this section, we assess the EU governance of water services after the 2008 financial crisis, which ushered in the NEG era in EU policymaking, first in the form of immediate crisis management in specific countries and then perpetuated in time and extended to all member states by the European Semester (Erne, Reference Erne2018, Reference Erne, Nanopoulos and Vergis2019).

As outlined in Chapter 2, the European Semester is a yearly process of coordination, scrutiny, and correction of member states’ economic and social policies. The Semester targets these policies in a bid to avoid fiscal and macroeconomic imbalances and to promote structural reforms. The main legal acts of NEG are the Council Recommendations on National Reform Programmes that the Council issues every year to each member state in the Semester process. These acts of the Council contain a set of country-specific recommendations (CSRs) on the measures that each member state should implement to achieve NEG’s goals. For those member states that received bailout packages, the Council Recommendations prescribed that they should follow the instructions of the Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) and their updates, that is, the legal documents attached to their financial assistance (bailout) programmes.

Given the country-specific methodology of the NEG regime, in this book we limit our analysis to four countries that represent the diversity of the EU in terms of size, geographical location, and economic development (including development of water infrastructure): Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania. Ireland and Romania were both subject to bailout programmes, so, in their case, the NEG framework gained an extra layer of importance.

How does the water sector feature in the NEG regime? First, the increasing surveillance of member states and the tighter integration of fiscal policies with structural reform in NEG enables EU-level actors to pursue a commodification agenda targeting the water sector by new and more efficient means (Golden, Szabó, and Erne, Reference Golden, Szabó and Erne2021). Second, the presence of the water sector in CSRs gives further proof of NEG’s comprehensive nature. Despite being relatively small in terms of GDP and employment share, water services feature in MoUs and CSRs, and the prescriptions are much more detailed than any previous legal instrument.

In the following, we present the findings of our analysis of NEG prescriptions relevant to the water sector in Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania. Our basic unit of analysis is the NEG prescription, that is, a specific statement calling on a member state to implement a certain policy measure or to achieve a specific policy goal (Chapter 5). We extracted these prescriptions from the NEG documents mentioned above: the country-specific Council Recommendations as well as the MoUs and their updates. As the water sector is not targeted only in explicit NEG documents, we extended our analysis to NEG prescriptions that target broader areas of which the water sector is part: that is, local public services, network industries, and public utilities.Footnote 2 We inferred whether these general prescriptions had relevance for the water sector by looking at supplementary information: the recitals of the Council Recommendations and Country Reports issued by the Commission as part of the Semester process. When analysing the policy orientation of a specific NEG prescription, we also considered its policy- and country-related semantic context (Chapters 4 and 5).

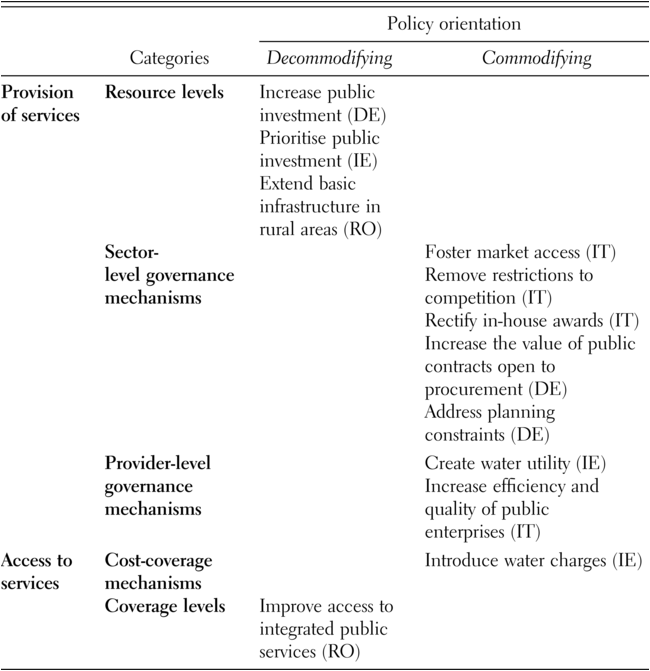

In this section, we analyse the policy orientation of NEG prescriptions in water services: whether they advocated commodification or decommodification and to what extent they added up to an overarching script. To achieve this goal, we first grouped the prescriptions using the categories of coverage levels and cost-coverage mechanisms (pertaining to people’s access to services) and of resource levels, provider-level governance, and sector-level governance (on the provision of services). These categories reflect the broad thematic target areas of NEG prescriptions, and commodification can mean different things in each of them, as demonstrated in Table 9.1, which summarises the main themes of the prescriptions. Following the discussions provided in our methodological Chapters 4 and 5, we recall here that the two main channels of commodification are linked to either a decrease in resources (curtailment) or the introduction of structural reforms (marketisation). The latter covers commodifying prescriptions in the categories of access and service-level and provider-level governance.

Table 9.1 Themes of NEG prescriptions on water services (2009–2019)

| Categories | Policy orientation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Decommodifying | Commodifying | ||

| Provision of services | Resource levels | Increase public investment (DE) Prioritise public investment (IE) Extend basic infrastructure in rural areas (RO) | |

Sector-level governance mechanisms | Foster market access (IT) Remove restrictions to competition (IT) Rectify in-house awards (IT) Increase the value of public contracts open to procurement (DE) Address planning constraints (DE) | ||

| Provider-level governance mechanisms | Create water utility (IE) Increase efficiency and quality of public enterprises (IT) | ||

| Access to services | Cost-coverage mechanisms | Introduce water charges (IE) | |

| Coverage levels | Improve access to integrated public services (RO) | ||

Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

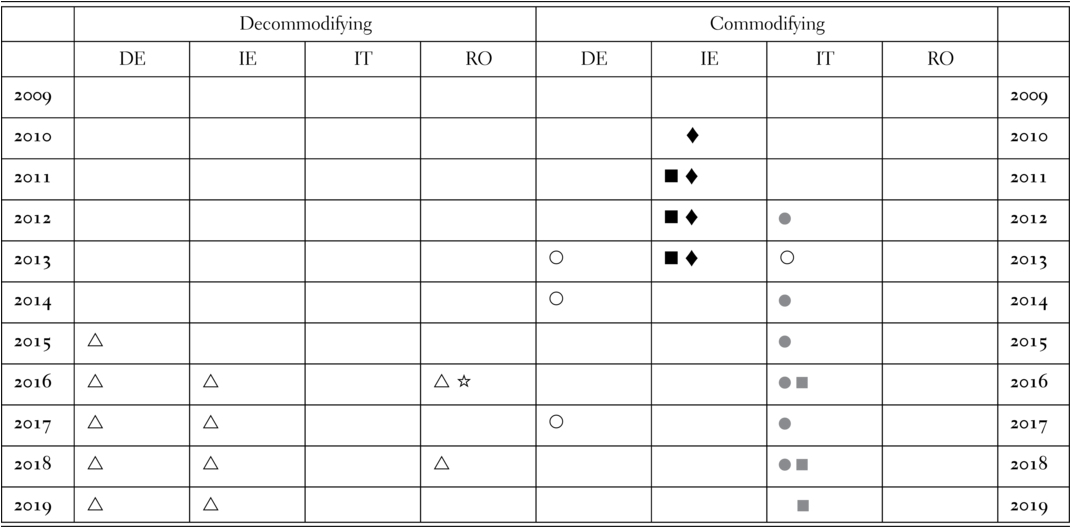

We provide an Online Appendix with the text of the policy prescriptions as they appeared in the NEG documents (Tables A9.1–A9.4). We have grouped them in tables according to the categories mentioned above and the main themes of the prescriptions. Before doing so, we analysed the recitals of the corresponding Council Recommendation and the Commission’s Country Report, also taking into account our own country-specific knowledge regarding the management of the water sector and its discontents. This analytical, context-specific approach enabled us to reveal the policy orientation of country-specific NEG prescriptions and the overarching policy scripts informing them. Table 9.2 accounts for the different degrees of coercive power of these NEG prescriptions in a given year and country, with MoU prescriptions having the strongest enforcement power and prescriptions issued without any reference to specific correction and sanctioning mechanisms having the weakest enforcement power (see Chapter 2; Jordan, Maccarrone, and Erne, Reference Golden, Szabó and Erne2021).

Table 9.2 Categories of NEG prescriptions on water services by coercive power

| Decommodifying | Commodifying | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | ||

| 2009 | 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ♦ | 2010 | |||||||

| 2011 | ■ ♦ | 2011 | |||||||

| 2012 | ■ ♦ | 2012 | |||||||

| 2013 | ⚪ | ■ ♦ | ⚪ | 2013 | |||||

| 2014 | ⚪ | 2014 | |||||||

| 2015 | △ | 2015 | |||||||

| 2016 | △ | △ | △ ☆ | 2016 | |||||

| 2017 | △ | △ | ⚪ | 2017 | |||||

| 2018 | △ | △ | △ | 2018 | |||||

| 2019 | △ | △ | | 2019 | |||||

Categories: △ = resource levels; ⚪ = sector-level governance; □ = provider-level governance; ☆ = coverage levels; ◊ = cost-coverage mechanisms.

Coercive power: ▲⦁■★♦ = very significant; ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() = significant; △⚪□☆◊ = weak. Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

= significant; △⚪□☆◊ = weak. Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

Table 9.2 presents the summary of the findings from our analysis. Commodification is the overarching theme that connects the NEG prescriptions across countries and over time. Of the four countries analysed here, only Romania did not receive prescriptions in the NEG framework to commodify its water sector. However, the lack of commodification prescriptions for Romania can be explained by the fact that the most profitable segments of the country’s water infrastructure were already in private hands. Since 2000, for example, a subsidiary of the French utilities TNC Veolia has been operating Bucharest’s water services under a twenty-five-year-long concession contract (Hall and Lobina, Reference Hall and Lobina2007: 70; PPI Project Database, 2016).

Germany, Ireland, and Italy all received commodification prescriptions, although with different thematic focuses, with varying degrees of coercive power and varying persistence over time. Ireland received prescriptions with very significant coercive power linked to bailout conditionality between 2010 and 2013. These prescriptions covered the categories of access to services and provider-level governance. The prescriptions issued to Germany and Italy addressed predominantly questions of competition between providers. The coercive power of the prescriptions for Italy was significant, except those issued in 2012 and 2013, whereas the coercive power of all prescriptions issued to Germany was weak throughout the whole period.

Table 9.2 also reveals that the main channel through which the NEG regime advanced commodification in the water sector was marketisation. There were no specific, commodifying prescriptions issued for the water sector in the quantitative, resource-level category. Even so, public water services were affected by the cross-sectoral prescriptions to curtail public spending (see Chapter 7). Instead, the water-specific commodifying prescriptions were all about making the management of water services more market-conforming, through structural reforms in the categories of cost-coverage mechanisms and provider-level and sector-level governance, starting with the MoU conditionality of the Irish bailout programme in 2010 to introduce water charges, all the way to Italy’s 2019 NEG prescription to make local public services more efficient.

Overall, decommodifying NEG prescriptions on the water sector were much less prominent. They had a shorter and a less persistent presence and a much weaker coercive power. Decommodification prescriptions started appearing only in 2015. They did not overwrite commodification prescriptions but rather ran parallel to them (commodification prescriptions continued to be issued to Italy up until 2019); this calls into question claims of scholars who saw a shift towards social prescriptions after 2014 (Zeitlin and Vanhercke, Reference Zeitlin and Vanhercke2018). We now proceed to analyse the prescriptions in more detail, across the four categories, in the order that they first appeared in CSRs or MoUs, starting with users’ access to services.

Prescriptions on Users’ Access to Water Services

Cost-coverage mechanisms: Among the four countries under study here, Ireland received the most detailed and explicit NEG prescriptions to commodify its water sector through the introduction of household water charges. The primary goal of the charges was to make user access conditional upon payment; therefore, these prescriptions fall under the category of access to services in general and cost-coverage mechanisms in particular. The establishment of a commercial relationship between service providers and users had links to the categories of resources for providers and provider-level governance. The original MoU of 2010 and its updates until 2013 repeated two general goals for Irish governments to follow: the transfer of responsibilities from local authorities to a national water utility (later to be named Irish Water; now Uisce Éireann) and the introduction of water charges.Footnote 3 The introduction of water charges is a clear example of how the NEG regime interpreted environmental principles in a commodifying way and how it used fiscal policy tools to promote marketising structural reforms.

The MoU signed in December 2010 committed the Irish government ‘to move towards full cost-recovery in the provision of water services’ (MoU, Ireland, 16 December 2010: Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, 8, paragraph 24), despite Ireland having received a derogation from the cost recovery principle in the EU WFD in 2000 to protect its system of financing water provision for domestic users from general taxation. The introduction of water charges in the bailout programme would have put an end to this derogation recognised in EU law.

The sixth update of the MoU committed the Irish authorities to ‘consider and provide an update on the general government debt and deficit treatment implications of establishment of Irish Water’ (MoU, Ireland, 6th update, 13 September 2012). The seventh and eighth updates demanded that, over time, the Irish government’s budget plans should ‘be based on Irish Water becoming substantially self-funded’ (MoU, Ireland, 7th update, 25 January 2013; 8th update, 12 April 2013).

The discussion of water charges in the context of cost recovery and government deficit would suggest that the main purpose of the introduction of the charges was related to the curtailment of public spending. Given the small share of the sector in government spending however, revenues expected from the introduction of domestic water charges would have provided only a small contribution to fiscal adjustment (European Commission, 2014c: 30). The primary goal of charging for water was therefore not to ensure the environmental protection of water, and not even to balance budgets, but to marketise access to water and introduce the cash nexus into the relationship between users and providers.

Updates to Ireland’s MoUs between 2011 and 2013 prescribed ever more detailed measures towards the introduction of water charges, including the collection of precise data on the progress of water meter installation. The ninth and tenth updates of the 2013 MoUs contain numerical annexes on ‘the quantum of pre-installation surveys completed, and water meters installed by geographical area’ (MoU, Ireland, 9th update, 3 June 2013; MoU, Ireland, 10th update, 11 September 2013). Nevertheless, the Troika left Ireland before the introduction of water charges and even before the installation of water meters had finished. The introduction of water charges triggered a long wave of social-movement and union protests in Ireland in 2014 and 2015, including a water bill boycott campaign supported by large sections of the Irish population, which eventually forced the government to suspend the charging system in 2016 (Hilliard, Reference Hilliard2018; Bieler, Reference Bieler2021; Moore, Reference Moore2023). After 2013, the EU’s NEG prescriptions no longer mentioned water charges, even though the Commission’s Country Reports continued to monitor Irish governments’ attempts to introduce them. By contrast, EU executives issued no prescriptions to Germany, Italy, and Romania on user access, as their water systems were already financed mainly by user charges and tariffs (Armeni, Reference Armeni2008; ver.di, 2010).

Coverage levels: Only Romania received a decommodifying prescription in the access to services category, pertaining to coverage levels. In 2016, Romania received an NEG prescription that urged the Romanian government to improve people’s access to integrated public services in disadvantaged rural areas where water and waste-water services are often simply lacking (Council Recommendation Romania 2016/C 299/18).Footnote 4 If one assesses this prescription in its semantic context, it appears to have been motivated by genuine concerns about social inclusion, but, compared with NEG’s countervailing commodifying prescriptions, this social prescription was much less specific. Neither the NEG prescription nor the corresponding Country Report (Commission, Country Report Romania SWD (2016) 91) outlined how such an extension of people’s access to public services could be financed. The prescription was also merely aspirational given its weak enforcement power, by contrast to those related to MoU-, excessive deficit-, or excessive macroeconomic imbalance procedures.

Prescriptions on the Provision of Water Services

Provider-level governance mechanisms: Marketising structural reforms formulated within the NEG framework did not only aim to set up new market-conforming rules for users’ access to water services. They also intervened in the ownership and internal operation structure of the public entities that provide these services. Here, we see a break with the methods of the ordinary legislative procedures that formally respected the neutrality of ownership principle laid out in Art. 345 TFEU (Golden, Szabó, and Erne, Reference Golden, Szabó and Erne2021). Breaking with this tradition, NEG prescriptions explicitly declared that governments should copy the more efficient private sector as the operating model for the water sector, even though they stopped short of calling for direct privatisation.

In Ireland, local governments provided water services until 2013, when, as part of MoU conditionality, a new law transferred water services to the newly incorporated national utility firm, Irish Water (Hilliard, Reference Hilliard2018). Although water charges were abolished in 2017 after sustained mass protest, the corporate model of service provision remained intact, with important commodifying implications for water workers who were going to lose local government employee status and the protections laid down in public sector collective agreements. To fend off this threat, in 2022, Irish unions secured an agreement at the Irish Workplace Relations Commission, whereby Irish Water and local authorities pledged that there would be no compulsory transfer of staff from local authorities to Irish Water (ICTU, 2022). This agreement, however, does not stop Irish Water from hiring new staff members on worse terms and conditions.

In Italy, NEG prescriptions outlined how the government should transform the operation of state-owned enterprises. In this area, the two most frequently repeated goals were the reform of publicly owned enterprises, on the one hand, and efficiency improvements, on the other, fitting the general principles of new public management (Kahancová and Szabó, Reference Kahancová and Szabó2015).

Sector-level governance mechanisms: Within the broader issues of sector-level governance, the introduction of market relations between providers dominated the prescriptions issued to Germany and Italy. The two countries received similar NEG prescriptions about improving market access and promoting competition between service providers. The prescriptions condemned the allegedly high share of in-house awards for the delivery of public services and promoted the opening up of these contracts to procurement procedures and concessions. Another NEG prescription, issued to Germany in 2013, called for an increase in the value of public contracts open to procurement (Council Recommendation Germany 2013/C 217/09). Although the content was similar, the tone of the 2014 prescription was less sharp, as it demanded only that the German government should ‘identify the reasons behind the low value of public contracts open to procurement under EU legislation’ (Council Recommendation Germany 2014/C 247/05). Germany continued to receive recommendations to enhance competition between 2014 and 2017 but with a specific focus on the railway sector (see Chapter 8) and, later, professional and business services. German local public services received one more commodifying prescription in 2017, when the CSRs identified planning constraints as a hindrance to investment.

The Italian case provides the most consistent example of how the NEG regime advanced commodification of the water sector through marketising reforms. Unlike in the German and the Irish CSRs, the commodifying prescriptions in the Italian CSRs were not counterbalanced by decommodifying prescriptions, and they formed a coherent theme even after the alleged social turn of the European Semester in 2014 (Zeitlin and Vanhercke, Reference Zeitlin and Vanhercke2018). Calls to open up local public services and network industries to competition appeared first in the Italian CSRs in 2012, prescribing the adoption of specific laws to achieve this goal. In particular, the 2013 Country Report for Italy picked water services as a negative example where no progress had been made in the promotion of competitiveness and efficiency, whereas it welcomed the separation of the operator from the network manager in the gas sector (Commission, Country Report Italy SWD (2013) 362). The Commission’s criticism came after Italian citizens voted in June 2011 by a more than 95 per cent majority to repeal the law that allowed the private sector to manage local public services. Incidentally, the centre-right Berlusconi government tried to invalidate this abrogative referendum in favour of public water services by calling on citizens to boycott it, but the Italian social movements and trade unions that had launched the referendum nevertheless succeeded, as it exceeded the 50 per cent participation quorum laid down in Italian law (Bieler, Reference Bieler2015). The abrogation of the law by referendum, however, did not prevent both centre-right and centre-left governments from reintroducing similar laws at national and regional level afterwards (Di Giulio and Galanti, Reference Di Giulio and Galanti2015; Erne and Blaser, Reference Erne and Blaser2018).

Resources for public water services: The decommodifying prescriptions issued for Germany, Ireland, and Romania focused on resources for providers. By contrast, Italy did not get any decommodifying prescriptions on water services. After 2015, Germany received prescriptions that tasked its government to increase investment in public infrastructure, particularly at local level. The emphasis on municipalities is crucial from the perspective of the water sector, as in Germany the provision of water services is the responsibility of municipalities, and at the same time municipalities were under severe fiscal pressure from the German debt brake (Schuldenbremse) and EU deficit rules (Bajohr, Reference Bajohr2015).

Investment in water also featured in NEG prescription issued to Ireland. Four of them directly and specifically dealt with the water sector between 2016 and 2019, tasking the Irish government to invest more in water services. Investment in water was never a stand-alone item but rather part of a broader productive, public infrastructure agenda. We labelled these prescriptions as decommodifying as seen in Table 9.2. Although the direction of NEG prescriptions on the resources for water was decommodifying, we must qualify this assessment on two counts.

First, the corresponding Irish NEG prescriptions from 2016 and 2017 used the term ‘prioritise government expenditure’ in the water sector, implying that additional public investment in the water sector must be counterbalanced by cutbacks in other areas (Council Recommendations Ireland 2016/C 299/16 and 2017/C 261/07). The same holds true in the Romanian case, where the 2016 NEG prescription on infrastructure projects in the waste-water sector called for a ‘prioritisation’ of investment in them (Council Recommendation Romania 2018/C 320/22).

Second, EU executives linked the need for increased investment to water charges as a potential source of extra funding (Commission, Country Report Ireland SWD (2016) 77: 62). The Commission’s Country Report also justified the need for more resources to compensate for the preceding ‘seven years of sharply reduced government investment’ that ‘have taken a toll on the quality and adequacy of infrastructure’ (Commission, Country Report Ireland SWD (2016) 77: 4 and 61). The report, however, is oblivious of the reasons why there was underinvestment in the first place. It did not mention that the MoUs’ cost-cutting recommendations had played their part in underinvestment.

Pursuing the Commodification of the Water Sector through NEG Prescriptions

To summarise the findings of our analysis of NEG prescriptions: we uncovered a transnational agenda of commodification in the water sector in Germany, Ireland, and Italy. We explained the absence of commodifying prescriptions for Romania by the fact that its government had already achieved the commodification of its lucrative urban water services in the run-up to EU accession. In the other three countries, NEG prescriptions continued the commodifying agenda that had its roots in the Commission’s legislative agenda preceding NEG, starting with the commodification turn of EU environmental laws and Commissioner Bolkestein’s attempts at water services liberalisation in the early 2000s. EU executives linked the introduction of water charges in Ireland explicitly to the WFD’s cost recovery principle, even though Ireland had secured an opt-out from it in EU law. NEG prescriptions targeted the Irish system of financing public water provision from general taxation, which the European Commission (2003: 14) had already denounced in 2003. EU executives also formulated the NEG prescriptions for Germany and Italy to open up local public water services to external competition in the spirit of Commissioner Bolkestein’s draft Services Directive (COM (2004) 2 final/3). The European Commission and the Council of finance ministers could do that, as the shift to the NEG regime empowered them to pursue an agenda that had been rejected by the European Parliament when it comprehensively excluded the water sector from the final Services Directive (2006/123/EC). Our analysis also revealed that commodifying prescriptions exclusively targeted qualitative characteristics of water governance through marketising structural reforms. By contrast, there were no water sector-related prescriptions that tasked member states to curtail the resources for them. We must, however, reiterate here that water services had also been affected by the prescriptions that tasked governments to cut public spending in general (see Chapter 7).

Concretely, all qualitative NEG prescriptions that targeted water services governance mechanisms, namely, those on cost-coverage mechanisms and provider-level and sector-level governance, pointed in a commodifying policy direction across all years and all countries. This means that they were informed by an overarching policy script of commodification. We also observed a few decommodifying prescriptions that called for quantitative changes, namely, more public resources for the German, Irish, and Romanian water sectors and an expansion of service coverage levels in Romania. These decommodifying prescriptions, however, were not only scarce and weaker in terms of their coercive power but also informed by a reasoning that did not contradict the overarching commodifying policy script of NEG, with one exception. All qualitative NEG prescriptions on the governance mechanisms for water services followed a common logic of commodification across countries and time, with the exception of Romania, which, as explained, had already privatised the lucrative water services in its urban areas in the run-up to its EU accession. Hence, NEG’s overarching commodification script extended to all country cases, regardless of their location in the EU’s political economy. At the same time, the coercive power of the corresponding NEG prescriptions still differed across them, ranging from very significant in the Irish case during the MoU period, to significant in the Italian case in the face of excessive economic imbalances, to weak in the German case, mirroring their different locations in the NEG enforcement regime at a given time.

Whereas all commodifying NEG prescriptions served the same overarching policy agenda, the decommodifying prescriptions received by Ireland, Germany, and Romania were semantically linked to other aims, namely, boosting competitiveness and growth, rebalancing the EU economy, social inclusion, or transition to a green economy. In the Irish case, EU executives linked several decommodifying prescriptions for more investments in the ailing water sector to investment prioritisation to boost competitiveness and growth. Hence, the aims that informed these prescriptions were compatible with further austerity in other areas that were not deemed as so critical to achieving this objective. The aim of boosting competitiveness and growth through more investments in water services also played a key role in Germany. By contrast to Ireland however, the investment turn in German NEG prescriptions was unqualified, as it extended to the entire public sector and to all levels of government. This echoes the presence of another objective in the German case, namely, NEG’s rebalancing of the European economy agenda. As increased public investments would boost domestic demand in Germany, they would also contribute to a reduction of the trade imbalance between Germany and other countries located in more peripheral positions of the EU economy (see Chapters 6 and 7). At the same time, EU executives continued to issue commodifying prescriptions that urged the German government to reform the mechanisms governing the water sector in a market-conforming way. In turn, the German government added a greater involvement of private capital and know-how in municipal infrastructure projects as a priority in its 2017 national reform programme (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2017: 17). Hence, the decommodification prescriptions that aimed to boost competitiveness and growth and/or to rebalance the EU economy did not go against NEG’s overarching commodification script (Chapter 11).

Romania and Ireland also received decommodifying prescriptions, which did not contradict NEG’s overarching commodification script. In 2018 and 2019, the Irish prescriptions on the prioritisation of public investment mentioned the role of ‘improved infrastructure’ as a ‘critical enabler’ for the ‘enhancement of private investment and productivity growth’ and not just for ‘balanced regional economic development’ and Ireland’s ‘transition towards a low-carbon and environmentally resilient economy’ (Council Recommendation Ireland 2018/C 320/07: Recital 12). The policy rationale of enhanced social inclusion, which clearly goes against NEG’s overarching commodification script, guided NEG water prescriptions only once, namely, in the case of the 2016 prescription that tasked the Romanian government to extend basic infrastructure ‘in particular in rural areas’ (Council Recommendation Romania 2016/C 299/18) to reduce Romania’s key development disparities ‘between urban and rural areas’ (2016: Recital 17). When EU executives repeated this 2016 prescription in 2018 however, they stressed the benefits of quality infrastructure for economic growth rather than social inclusion (Council Recommendation Romania 2018/C 320/22: Recital 19), even though large parts of Romania’s rural population still had no access to safe drinking water, by contrast to all EU countries and even many developing countries (see footnote 4). If we consider the scarcity and the weak coercive power of the prescriptions that were at least partially informed by social concerns, we can hardly speak about a social turn of the NEG regime (Zeitlin and Vanhercke, Reference Zeitlin and Vanhercke2018). Likewise, the equivocal semantic links between the weak 2018 and 2019 prescriptions on the prioritisation of public investment in water services for Ireland and the transition to a green economy hardly warrant speaking about an ecological shift in the NEG regime either. Whereas these semantic links prefigured the growing importance of a green agenda in the post-Covid NEG regime (Chapter 12), our preceding analysis of the market terminology in the WFD indicates that the growing salience of green concerns does not necessarily lead to a policy shift in a decommodifying direction.

EU Governance of Water Services by Law after the Shift to NEG

EU executives pursued a water services commodification agenda already before 2009, but their NEG prescriptions went further, as the scope of NEG interventions was much more ambitious. NEG prescriptions in the water sector targeted areas that were considered taboo during earlier phases of EU integration, such as directly prescribing a change in the legal status or operating principles of public services. We should add, however, that the interaction between ordinary legislative procedures and NEG went in both directions. NEG has not replaced the traditional sources of EU authority. The EU’s ordinary legislative processes run parallel with NEG mechanisms, including in the water sector. There have been four prominent cases of intervention or intervention attempts by ordinary EU laws in the water sector since the shift to NEG after the financial crisis: namely, the Concessions Directive (2014/23/EU), the revised Procurement Directives (2014/24/EU, 2014/25/EU), and the recast of the Drinking Water Directive (2020/2184).

A concession is a long-term contractual relationship between a contractor and a service provider, a step beyond the short-term (one-off) and unidirectional relationship of procurement. As the contractor is typically a public body and the provider is a private firm in these relationships, the legal form of the concession is closely linked with the increased use of PPPs (Porcher and Saussier, Reference Porcher and Saussier2018). In 2011, the Commission proposed a stand-alone directive on concessions, which would have facilitated the use of the concession model in water services across the EU. The Concessions Directive would have benefitted French water TNCs, as concessions law was the legal framework that contributed to their successful long-term operation in France (Guérin-Schneider, Breuil, and Lupton, Reference Guérin-Schneider, Breuil, Lupton and Schneier-Madanes2014). The spread of the concession model to other parts of the EU would have vested these companies with a competitive advantage over other service providers that were used to a different legal regime. In reaction to the success of the Right2Water ECI, however, the Commission excluded water from the final scope of the directive (see section 9.4). The parallel development of the NEG regime and policymaking by ordinary EU laws is also shown by the fact that Germany received NEG prescriptions to increase the value of contracts open to public procurement in 2013 and 2014, that is, the same years when EU legislators revised the Procurement and Concessions Directives.

Whereas the draft Concessions Directive attempted to commodify water services through ordinary EU laws, the recasting of the Procurement Directives and the DWD also included potentially decommodifying policy features. The legislative procedure for the Concession Directive ran in parallel with the recasting of the Procurement Directives. Pressure from unions and social movements, including the European Federation of Public Service Unions (EPSU), forced the inclusion in the Procurement Directives of stipulations about social and environmental clauses in procurement calls (see Chapter 7; Fischbach-Pyttel, Reference Fischbach-Pyttel2017). Likewise, the recast DWD dealt with a social question in detail, namely, that of people’s access to drinking water. Art. 16 of the directive advances the decommodification of water by obliging member states to improve or maintain access to safe drinking water for all, with a focus on the most vulnerable social groups. The non-binding Pillar of Social Rights adopted by all EU institutions in 2017 included water as an essential service with access rights for everybody, but the new DWD gave a more tangible expression to this principle (EPSU, 2021).

Both the exemption of water from the Concessions Directive and the inclusion of water access rights in the DWD were prompted by the pressure that social movements exerted on EU policymakers, namely, through the Right2Water ECI coordinated by EPSU. The transnational countermovements fighting for the right to water at European level, however, started much earlier. They are the subject of section 9.4.

9.4 Transnational Countermovements against the Commodification of Water

So far, we have assessed EU executives’ attempts to commodify water services, either through the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure or its country-specific NEG prescriptions. We now assess the protests by social movements and unions that they triggered. National and transnational protest movements successfully blocked several commodification attempts; for example, the inclusion of water and sanitation services in the commodifying EU Services Directive and the introduction of water charges, as requested by the NEG prescriptions for Ireland (Moore, Reference Moore2018, Reference Moore2023; Bieler, Reference Bieler2021). In contrast, these countervailing protest movements were less effective in advancing a proactive agenda of enshrining the right to water in EU law.

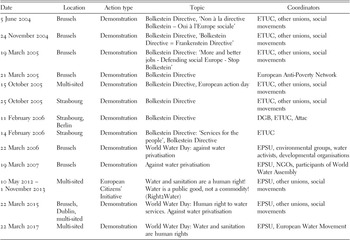

EPSU had played an important role in the transnational countermovements in the sector since the mobilisations against Commissioner Bolkestein’s plan to include water in the services directive. The Bolkestein Directive had been important, as it was then that the ‘Commission first showed its true colours’ (interview, member of the European water movement and EPSU official, Brussels, December 2018). Since then, EPSU has been co-organising several transnational mobilisations politicising the EU governance of water services, namely, for the right to water and against the privatisation of water services, as shown in Table 9.3, which is based on the transnational protest database (Erne and Nowak, Reference Erne and Nowak2023).

Table 9.3 Transnational protests politicising the EU governance of water services (1993–2019)

| Date | Location | Action type | Topic | Coordinators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 June 2004 | Brussels | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive, ‘Non à la directive Bolkestein – Oui à l’Europe sociale’ | ETUC, other unions, social movements |

| 24 November 2004 | Brussels | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive, ‘Bolkestein Directive = Frankenstein Directive’ | ETUC, other unions, social movements |

| 19 March 2005 | Brussels | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive: ‘More and better jobs - Defending social Europe - Stop Bolkestein’ | ETUC, other unions, social movements |

| 21 March 2005 | Brussels | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive | European Anti-Poverty Network |

| 15 October 2005 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive, European action day | ETUC, other unions, social movements |

| 25 October 2005 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive | ETUC, other unions, social movements |

| 11 February 2006 | Strasbourg, Berlin | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive | DGB, ETUC, Attac |

| 14 February 2006 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Bolkestein Directive: ‘Services for the people’, Bolkestein Directive | ETUC |

| 22 March 2006 | Brussels | Demonstration | World Water Day: against water privatisation | EPSU, environmental groups, water activists, developmental organisations |

| 19 March 2007 | Brussels | Demonstration | Against water privatisation | EPSU, NGOs, participants of World Water Assembly |

| 10 May 2012 –1 November 2013 | Multi-sited | European Citizens’ Initiative | Water and sanitation are a human right! Water is a public good, not a commodity! (Right2Water) | EPSU, other unions, social movements |

| 22 March 2015 | Brussels, Dublin, multi-sited | Demonstration | World Water Day: Human right to water services. Against water privatisation | EPSU, other unions, social movements |

| 22 March 2017 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | World Water Day: Water and sanitation are human rights | EPSU, European Water Movement |

The table includes protest events targeting political authorities in relation to the European governance of water services, using the database’s political level category, excluding socioeconomic protests at company, sectoral, and systemic level.

The transnational protest events in the European water sector targeted EU executives’ vertical attempts in favour of water commodification, starting with Commissioner Bolkestein’s proposal for an EU Services Directive in 2004. In comparison with the transport sector, which had already been facing commodifying EU interventions much earlier, we did not find any evidence of transnational protests in the water sector before that date (see Chapter 8). In the Bolkestein case, EPSU was a leading organiser within a broad coalition against this directive. EPSU also used its links to members of the European Parliament, convincing it to push back against the Commission’s most radical proposals and to remove the most controversial elements of the directive (Crespy, Reference Crespy2016). Bolkestein’s failed attempt to commodify water services also shaped subsequent struggles. The experience of mobilisation against Bolkestein played a significant role in EPSU’s decision to launch its ECI on the right to water, which turned out to be the first successful ECI in EU history (Fischbach-Pyttel, Reference Fischbach-Pyttel2017: 187; Bieler, Reference Bieler2017; Szabó, Golden, and Erne, Reference Szabó, Golden and Erne2022).

The Commission registered EPSU’s ECI on the right to water in May 2012 under its full title: ‘Water and sanitation are a human right! Water is a public good, not a commodity!’. EPSU was the first organisation to be able, in close collaboration with social movements, to collect the one million signatures required to make this new instrument of direct democracy legally valid at EU level. The final number of signatures submitted to the European Commission in December 2013 was 1,659,543, surpassing the ECI’s national-level signature thresholds in thirteen countries (Szabó, Golden, and Erne, Reference Szabó, Golden and Erne2022), even though ECIs must reach the thresholds, which are linked to population size, in only seven EU member states to be legally valid.

As the full title of the initiative indicates, EPSU mobilised the public by uniting defensive and proactive goals: defending water from commodification, on the one hand, and securing the human right to water, on the other. By focusing its struggle on the fight against commodification and privatisation, EPSU identified concrete negative practices against which popular discontent could be targeted: the pro-commodification policy ideas of the Commission and the lobbying of big TNCs active in water services, such as Veolia and Suez.

The other leg of the Right2Water campaign, fighting for water to become a human right, was encompassing enough to form the basis of a broad coalition, as the campaign united actors with different ideas on the details of water management and financing. Many organisations in the campaign were against water charges altogether. Others, such as the German union ver.di, one of the most active national organisations in the campaign, had a much more nuanced view on the subject. Ver.di supports domestic water charges if they guarantee the independence of non-commercial, local public providers, sustainable water management, the provision of good quality service, and decent working conditions in the sector (ver.di, 2010).

What did the Right2Water ECI achieve in substantive terms, apart from obliging the European Commission to issue a formal response? The defensive aspect of the campaign was successful, as the Commission excluded water from the scope of its draft Concessions Directive in June 2013 (Directive 2014/23/EU: Art. 12) even before the official conclusion of the ECI campaign. Although this was not a pre-defined target of the ECI campaign, the Concessions Directive caught campaigners’ attention, especially in Germany (Parks, Reference Parks2015: 72). In contrast, the proactive goal of securing water as a human right at European level proved to be a more challenging task for the initiative’s organisers. EPSU’s ultimate goal was to include strong legal guarantees of water decommodification with strong enforcement power. In other words, EPSU wanted to ensure EU laws that contained detailed mechanisms securing affordability and access to water for everyone. By contrast to the Commission’s swift move to exempt water from the Concessions Directive, the revision of the DWD in a decommodifying direction was a drawn-out process of fits and starts, where EPSU often found itself on the margins of power struggles between EU institutions. Although EPSU submitted the ECI in December 2013, it took eight years to revise the DWD. Eventually, EPSU commended EU legislators’ inclusion of access rights to safe drinking water in the recast DWD as a step in the right direction but still considered it insufficient (EPSU, 2021).

What is the relationship between the Right2Water ECI campaign and the NEG regime? The collection of signatures for the ECI took place over the years 2012–2013, coinciding with the peak of EU executives’ commodifying NEG prescriptions for member states’ water sectors. As shown in Table 9.2, in 2013, Germany, Ireland, and Italy simultaneously received commodifying NEG prescriptions that were relevant for their water sector. Even so, the ECI campaign did not achieve equal levels of support across the three countries.

The ECI received the strongest support in Germany out of all the EU member states in terms of absolute number of signatures and also regarding the number of collected signatures versus the required national validity threshold (1,236,455 versus 74,250, respectively, meaning that, if there had not been a requirement to pass the threshold in other member states too, Germany alone would have been able to carry the entire initiative). The German field operation of the ECI campaign relied on a broad coalition of unions and NGOs, many of which had long-standing experience in local struggles against water privatisation (Erne and Blaser, Reference Erne and Blaser2018; Moore, Reference Moore2018; van den Berge et al., Reference van den Berge, Boelens, Vos, Boelens, Perreault and Vos2018). Furthermore, the signature collection received a boost from a popular TV show (Die Anstalt), which mentioned the campaign and linked it to looming threats coming from the proposed Concessions Directive (Parks, Reference Parks2015). We also noticed a link between the plans for a Concessions Directive and the 2013 NEG prescriptions for Germany demanding an increase in the value of public contracts open to procurement. Concessions and procurement are separate mechanisms but have similar goals: they both target the relationship between public and private service providers.

The ECI organisers also had strong links to activists in Italy. The Italian Water Movements Forum (Forum Italiano dei Movimenti per L’acqua) was the main force behind a national referendum that repealed a law allowing private management of local public services in 2011, as mentioned above (Bieler, Reference Bieler2021 and Reference Bieler2017). Nonetheless, the ECI barely passed the threshold of 54,750 signatures in Italy with a final tally of 65,223. This could be due to organisers’ fatigue and because abrogative Italian referendums do not preclude the reintroduction of similar laws by regional and national lawmakers afterwards (Di Giulio and Galanti, Reference Di Giulio and Galanti2015; Erne and Blaser, Reference Erne and Blaser2018). EU executives’ subsequent NEG prescriptions therefore recurrently tasked the Italian government to introduce such legislation to increase competition in local public services, despite the negative result of the 2011 referendum (Bieler, Reference Bieler2021: 87; van den Berge et al., Reference van den Berge, Boelens, Vos, Boelens, Perreault and Vos2018: 237).

Despite Ireland receiving several coercive NEG prescriptions between 2010 and 2013 that explicitly demanded measures to commodify its water sector, the few Irish Right2Water ECI campaigners at the time did not collect enough signatures to pass the required national ECI threshold. We attribute this in part to the time lag between the issuing of NEG prescriptions and their implementation by the Irish government. As discussed in section 9.3, the Troika left Ireland before the introduction of water charges and before the installation of water meters had been completed. The Irish Right2Water protests against the installation of water meters and the introduction of water charges intensified only gradually over the course of 2014, with a water charges boycott campaign and mass demonstrations at the end of that year (Bieler, Reference Bieler2021; Moore, Reference Moore2023). The abolition of newly introduced water charges also became a central issue during the 2016 general election campaign; thus, water charges were in effect abolished in 2017 (Hilliard, Reference Hilliard2018). Despite this apparent disconnect in the timing of popular mobilisation in mainland Europe and Ireland, there were significant links between the Irish and European campaigns. First, the Irish campaign borrowed its Right2Water slogan directly from the Right2Water ECI. Second, Sinn Féin’s Lynn Boylan, member of the European Parliament in the left-wing GUE/NGL group between 2014 and 2019, was not only directly active in the Irish campaign but also coordinated the EU work on the follow-up to the Right2Water ECI as European Parliament rapporteur.

9.5 Conclusion

Vertical EU interventions in the governance of the water sector combine internal market rules and environmental policy. In this chapter, we have analysed the policy orientation of EU interventions in both areas before and after the EU’s shift to its NEG regime in 2009.

EEC legislators had already started intervening in the water sector in the 1970s and 1980s to set harmonised standards on water quality. The first European directives related to the creation of the common market but nevertheless pointed in a decommodifying direction, as they aimed to guarantee a level playing field by taking water quality standards out of regulatory competition between member states. In the 1990s, ecological concerns and neoliberal views became an important motivation for the adoption of EU water and waste-water directives, which increasingly pointed in a commodifying policy direction. Despite the increasing interest of private capital in water management, however, the role of horizontal market pressures as a driver of water service commodification remained limited. In most member states, public administrations continued to manage water as a public service. In some cases, municipalities even brought them back under public management after having privatised them beforehand (Hall and Lobina, Reference Hall and Lobina2007; Kishimoto, Gendall, and Lobina, Reference Kishimoto, Gendall and Lobina2015). At the same time, most attempts by EU executives to create a European water services market by law failed, principally as a result of popular protests that led to the exclusion of the water sector from the final version of the 2006 Services Directive.

The financial crisis of 2008, however, ushered in a new era in water politics, as the shift to NEG gave EU executives new powers to pursue commodifying policy reforms. Although the amount of public spending on water was tiny in comparison with that for other public sectors, such as healthcare (see Chapter 10), all countries in our sample received commodifying NEG prescriptions; except Romania, which had already privatised its lucrative, urban water services in the run-up to its EU accession. Strikingly, all qualitative NEG prescriptions on the governance of water services or people’s access to them pointed in a commodifying direction, regardless of time or the different positions of Germany, Ireland, and Italy in the EU’s political economy. Even under NEG however, the proponents of water commodification found it difficult to realise their ambitions. EU executives failed to commodify water services even where they could rely on NEG prescriptions with very significant coercive power, namely, in Ireland during the Troika years. After 2015, EU executives began issuing quantitative NEG prescriptions on water services that pointed in a decommodifying direction. Most of them tasked member states to increase or prioritise public investments, not for social reasons but to rebalance the European economy and to increase its competitiveness. Concerns about enhanced social inclusion played a role in only one case, namely, the 2016 NEG prescriptions for Romania that tasked its government to improve users’ access to integrated public services in disadvantaged rural areas. During the same period, EU legislators continued to exclude water services from commodifying EU directives, as happened in the case of the Concessions Directive (2014/23/EU). As discussed in Chapter 7, political countermovements forced the Commission to abandon its draft Services Notification Procedure Directive (COM (2016) 821 final), which would have obliged public authorities (including municipalities) to seek Commission approval before implementing any national or local laws, regulations, or administrative provisions on services covered by the 2006 Services Directive.

The main obstacle holding up these commodifying EU interventions was the rise of social movements and unions defending public water services at both EU and national level. EU executives’ vertical commodification attempts triggered transnational countermovements for water as a human right, culminating in the successful Right2Water ECI. Commodifying NEG prescriptions on water services also ignited strong popular resistance, as the backlash against the introduction of water charges in Ireland has shown. Hence, the overarching commodifying policy orientation of vertical EU interventions in the water sector triggered successful, national and transnational, countermovements (Bieler, Reference Bieler2021; Szabó, Golden, and Erne, Reference Szabó, Golden and Erne2022; Moore, Reference Moore2023). The failed water commodification attempts by both EU laws and NEG prescriptions until 2019, however, did not stop EU executives from pursing these goals by new means afterwards. Although the post-Covid pandemic NEG regime substantially increased the space for public investments, member states’ access to EU recovery and resilience funding remained conditional upon the implementation of further commodifying public sector reforms, as we discuss in Chapters 12 and 13.