In the fall of 2017, as #MeToo, a mass social media movement against sexual abuse and harassment, emerged, the Parliament of Canada considered the omnibus Bill C-51 which included the latest amendments to the sections of the Criminal Code of Canada [the Code] aimed at enhancing the rights of sexual assault complainants. Bill C-51 would endow complainants with a formal right to appear and be represented by counsel in admissibility hearings and restrict the admissibility of records in the possession of the accused. The Government justified these reforms as necessary to address public concern that, despite the existing protections, rape myths and sexist stereotypes continue to be relied upon in sexual offence proceedings.

Bill C-51 was the latest in a long line of amendments to the Code to address the inadequate treatment of complainants. Since the inception of these “rape shield” provisions in 1983, they have been subjected to repeated legislative and judicial revision. Despite this almost continuous institutional activity, several scholars have identified a stubborn “justice gap” between what the rape shield says as a matter of black letter law, and how these provisions are undermined in the courtroom (Craig Reference Craig2016a; Gotell Reference Gotell2002; Lazar Reference Lazar2015; Ehrlich Reference Ehrlich and Sheehy1999; Vandervort Reference Vandervort and Sheehy2012). Our research suggests that the persistence of the “justice gap” can be attributed, at least partially, to institutional and political factors: Parliaments past and present have failed to fully appreciate and respond to the implementation critique. We argue that, while the impetus for introducing rape shield and related legislation is to protect the equality and privacy rights of sexual assault complainants, the legislative process of these “policy cycles” disproportionately focuses on remedying due process concerns, at the expense of considering the problems that arise in judicial implementation of the provisions.

In our study, we employ a framework from the public policy literature to help explain why legal reasoning premised on rape myths and sexist stereotypes will continue to periodically pervade sexual assault proceedings under Bill C-51. To better understand this latest cycle of rape shield policy, it is necessary to account for earlier rape shield reforms and their implementation. To capture as much of the institutional dynamics as possible, we employ a broad and inclusive notion of the “rape shield.” Some legal practitioners and scholars use the term “rape shield” narrowly to refer only to section 276 of the Criminal Code, which outlines the procedures for how and when sexual history evidence of a sexual assault complainant can be used in criminal proceedings. Here, the term “rape shield” is used to describe and discuss the range of existing legislative measures intended to protect sexual assault complainants in the judicial process that can be found mainly, but not exclusively, in sections 276–278.97.Footnote 1 While sections 276–277 stipulate the rules of how sexual history evidence can be used in court, sections 278.1–278.91 detail the restrictions on how and when the personal records of a sexual assault complainant can be produced to the defence. Bill C-51 added sections 278.92–278.97 to the Code, which govern the use and admissibility of records relating to the complainant that are already in the possession of the accused. Even though the provisions are different, they share a clear overlapping objective: to protect sexual assault complainants from trial tactics which rely on rape myths and sexist stereotypes.

We situate Bill C-51 as part of these “rape shield” protections and consider it within its historical-institutional context of successive policy cycles. A historical analysis of the preceding policy cycles suggests that the legislative process privileges due process over implementation concerns. In order to further explore this preliminary observation in its most current context, we conducted a quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the transcripts from the House of Commons readings for C-51, as well as of the transcripts from the hearings held by the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. This approach follows several recent studies utilizing a similar methodology to assess policy outcomes (see, for example, Monk Reference Monk2010; Russell and Cowley Reference Russell and Cowley2016; Fuji Johnson, Burns, and Porth Reference Fuji Johnson, Burns and Porth2017), but we expand the analysis by also considering the quality and content of the witnesses’ engagement in deeply contentious policy debates at the Committee stage. Our detailed study of Bill C-51’s legislative process demonstrates what we suspected of previous policy cycles: implementation problems are minimized while legal and constitutional questions dominate. This is consistent with some critiques of the “judicialization of politics,” in which “questions of social and political justice will be transformed into technical legal questions” (Russell Reference Russell1983, 52) such that public policy choices and deliberations are distorted by judicial interventions or the prospect thereof (Morton Reference Morton1987). We also trace some of the institutional and structural obstacles built into the legislative process that create serious impediments for Parliamentarians to effectively legislate in the area of sexual assault trials. We conclude that if Parliamentarians are truly committed to making the trial process for complainants of sexual assault more humane, they will need to be more cognizant of implementation failures. An effective response to the implementation critique may even require a more responsive and flexible legislative process.

What is a “Policy Cycle”?

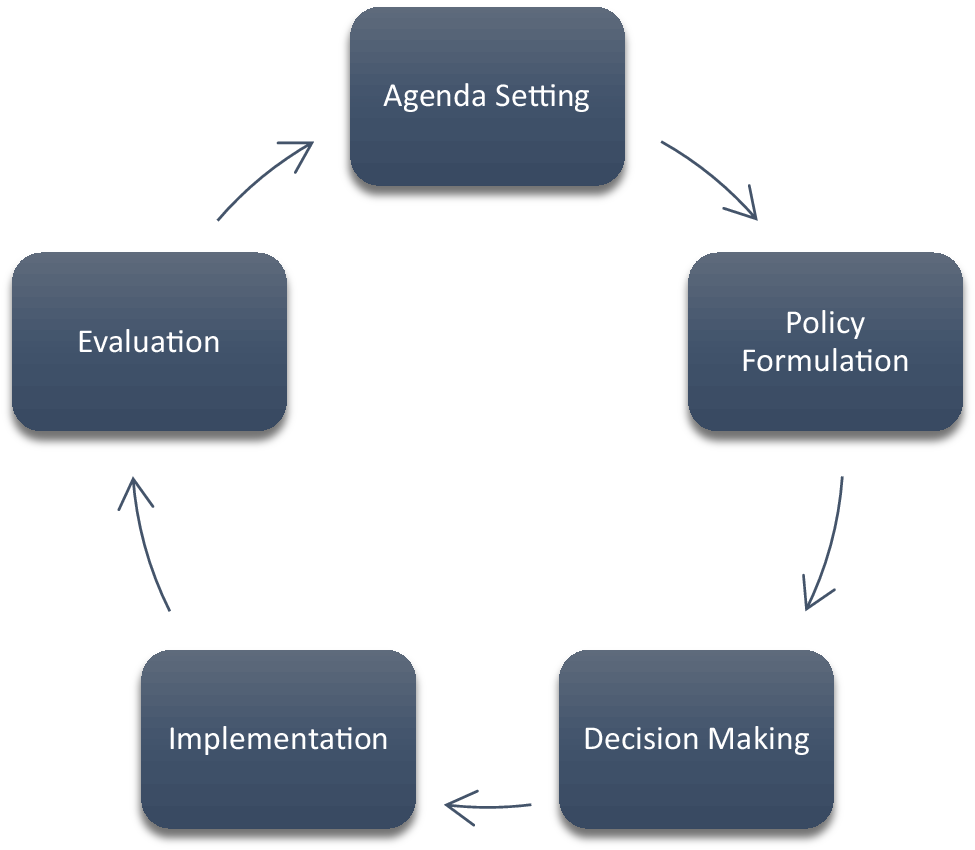

Our study uses a “Policy Cycle” framework that theorizes that government policy moves through five stages: Agenda Setting, Policy Formulation, Decision Making, Implementation, and Evaluation (Figure 1) (Howlett, McConnell, and Perl Reference Howlett, McConnell and Perl2017). A policy cycle begins at the agenda setting stage, where a potential problem is identified and clearly defined to determine whether it warrants further attention and state resources (Brewer and deLeon Reference Brewer and deLeon1983, 18). The policy-formulation and decision-making stages are characterized by wide-ranging debate over the means to resolve the identified policy problem. During these stages, the government engages in a “legitimation process,” selecting the most appropriate form of public action to achieve the desired policy goal. Successful policy legitimation requires the consultation of “field actors” to ensure that the practical and institution-specific conditions of their work are considered (Isallys Reference Isallys, Eliadis, Hill and Howlett2005, 171). At the end of the decision-making stage, the final version of the policy is agreed upon and if legislation is warranted then it should ideally be drafted in precise language with an enforcement or accountability mechanism. The implementation stage follows once the selected policy is executed “in the field.” Implementation has its own set of participants and practices, often identified as a local institutional culture, so it is desirable in the prior stages for policymakers to anticipate and appreciate potential barriers for the policy to be implemented as intended (Brewer and deLeon Reference Brewer and deLeon1983, 19). Finally, the last stage of the heuristic model is the evaluation stage. Here, the policy and its implementation are formally assessed, and criteria are established to measure the performance of the policy. In this context, judicial decisions on constitutionality serve as a form of “evaluation” and spur new policies; while these are not formal “policy evaluations” in the traditional sense, the Court’s use of analytical tools, like the section 1 tests of “proportionality,” require some assessment of effectiveness that is akin to an evaluation in other policy areas.

Figure 1 Stages of the Policy Cycle

With the evaluation providing the impetus for a new cycle, the expectation is that subsequent cycles will improve the policy (Brewer and deLeon Reference Brewer and deLeon1983, 20). Policy development is thus conceived as cyclical, with no temporal limit on how long a particular cycle can span or how many cycles in total may occur. In order for policy to adapt with each rotation, “feedback” is a necessary communicative process whereby the “output” or effect of policy is responded to by the “input” of front-line implementers (Jann and Wegrich Reference Jann, Wegrich, Fischer, Miller and Sidney2006, 44). Under ideal conditions, policy should improve each time it progresses through a rotation, eventually arriving at a theoretical “best possible policy.”

As one can infer from the invocation of terms like “ideal” and “theoretical,” actual policy development is usually messier, contingent, and often obscured by bureaucratic secrecy. For sure, the policy cycle heuristic systematically underplays the chaotic nature of an overall policy web, where policy is influenced by competing forces and complex interactions between interested actors and existing programs, laws, and norms (Jann and Wegrich Reference Jann, Wegrich, Fischer, Miller and Sidney2006, 56). For any contentious area of policy, one can expect irreconcilable deeply held values that may also skew the rationality modelled by the cyclical framework. Most crucially of all, it is difficult to evaluate the accuracy of Canadian policymaking as a progression of cycles given that almost all of the crucial decisions are made behind closed doors. To become law, policy must be justified in Parliament, but, as political scientists have long recognized (Wheare Reference Wheare1963), legislatures in the Westminster system are oriented more towards legitimation and critiquing than “law-making” and deliberation. Many laws, for example, look at the end of the Parliamentary process much as they did at the beginning.

Why, then, rely on legislative debates to tell us anything meaningful about policy development, and why impose an artificial cycles heuristic on an unruly policy process? To some extent, it is borne of necessity: interviews with bureaucrats—if you can get them—may not be candid, and Cabinet documents are often shielded from disclosure. Given this context, it is defensible to use on-the-record statements by the Government about its legislation and the critiques offered by Members of Parliament and committee members to capture the dynamics and considerations that are likely at play throughout the entire policy development process (Monk Reference Monk2010, 7–8). And while the policy cycle is an artificial simplification, its usefulness is as a heuristic: it allows us to focus on the aspects of policy development that might otherwise be entirely invisible and allows us to organize considerations in a manner that replicates a rational policy-maker even if reality makes the stages of the cycle blurrier than their idealization. The usefulness of the policy cycle explains its enduring appeal in the public policy literature, where it has been recognized as a necessary and vital foundational tool (Sabatier Reference Sabatier2007, 4).

For the purpose of our study, the policy cycle approach offers a framework to empirically evaluate the dynamics behind the new rape shield provisions. It helps simplify decades of complex and subtle policy reform in the area of the rape shield, not just legislative change but also its judicial interpretation and articulation (and, as discussed below, judicial interpretations and judicial behaviour dominate the policy cycles in the rape shield saga). Focusing on specific stages of the policy process, such as the implementation stage and the evaluation stage, allows us to pinpoint where the rape shield policy drifted from its original purpose and to make informed suggestions for how a future rape shield policy might be more successfully implemented. Overall, while we recognize that policy development is often messier than outlined by the formal policy cycle, for the purpose of our study, the policy cycle approach allows us to evaluate the new provisions through clear and informed criteria, to simplify decades of complex, inter-institutional policy reform, and to situate Bill C-51 within its historical context.

Evaluating the Rape Shield’s Policy Cycles

Policy Cycle One: The Original Rape Shield (1982–1991)

In 1982, New Democratic Party (NDP) Member of Parliament (MP) Margaret Mitchell raised the issue of violence against women and demanded that the Liberal government put gendered violence on the forefront of its policy agenda. This coincided with political action from various women’s groups identifying existing sexual violence laws as minimal and sexist (Alphonso and Farahbaksh Reference Alphonso and Farahbaksh2009) and built upon a generation of feminist legal critiques of sexual assault jurisprudence (see Boyle Reference Boyle1984 for this history). The Liberal Government of Pierre Trudeau introduced Bill C-127 (1982) to reform several laws pertaining to sexual violence and to establish Canada’s first rape shield law (s. 276), with intent to eliminate (or at least reduce) prejudicial attitudes towards victims (Johnson Reference Johnson and Sheehy2012, 614). This was the first legislation to provide sexual assault complainants with expanded evidentiary protections, restricting the right of the defence to adduce evidence relating to the sexual history of the complainant, eliminating the corroboration requirement, as well as removing the onus on complainants to “report in a timely manner” (Tang Reference Tang1998, 262). These measures were understood as protecting both the privacy and equality rights of sexual assault complainants, but also protecting the trial process itself, since rape myths and lines of reasoning premised on irrational stereotypes distort the truth-seeking and adjudicating functions of the court.

Bill C-127 was implemented in January of 1983 and later challenged in R. v. Seaboyer ( 1991 ). Seaboyer was charged with sexually assaulting a woman, and, at the preliminary inquiry, his counsel was restricted from cross-examining the complainant about her past sexual conduct in order to investigate whether someone else could have caused her bruises on a different occasion (Seaboyer, 598). Seaboyer argued that preventing him from pursuing this potential defence violated his due process rights under sections 7 and 11 of the Charter. A majority of the Supreme Court of Canada agreed and struck down s. 276, emphasizing that, while the objective of abolishing “outmoded, sexist-based use of sexual conduct evidence” is laudable, the legislation “oversho[t] the mark,” making it possible that relevant probative evidence might be ignored and lead to wrongful convictions (Seaboyer, 625). Justice L’Heureux-Dubé offered a strong dissent (joined by Justice Gonthier). She found the provisions a “measured and considered” response, especially since Parliament had a justified “distrust of the ability of the courts to promote and achieve a non-discriminatory application” of sexual assault law (706). She notes that further judicial discretion can hardly be the solution since “[h]istory demonstrates that it was discretion in trial judges that saturated [sexual assault law] with stereotype” in the first place (708). Nonetheless, with the law now inoperative, the majority’s decision offered Parliament guidance for a rape shield that would pass constitutional muster—but it would require a return to the trial court discretion L’Heureux-Dubé eschewed. Any restriction on sexual history evidence must not be a “blanket exclusion” and, instead, sexual history evidence should be permitted as long as it was germane to the defence and not “stand alone” or misleading (Seaboyer, 495). Still, Justice McLachlin emphasized that trial judges must not allow sexual history evidence to be used in a manner which promotes the “twin myths,” that “unchaste women” are more likely to have consented to the sexual activity in question and that, by virtue of their past sexual history, they are less worthy of belief (Seaboyer, 634). The first policy cycle, then, came to an ambiguous ending as the objectives of the shield were judicially confirmed as imperative, but the provisions themselves found to be constitutionally wanting.

Policy Cycle Two: A New Rape Shield Regime (1992–1996)

In the wake of Seaboyer, the rape shield reappeared on the policy agenda of the Government and a revised shield was drafted as Bill C-49 in 1992. The new legislation was carefully crafted to ensure compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision. In fact, the statutory language drew from the majority decision in Seaboyer, demonstrating a genuine engagement with the due process deficiencies identified by the Court, even if it impaired the effectiveness of the legislation. This shows that the results of the previous policy evaluation stage are reflected at the new policy formulation stage. C-49 allowed for the admission of evidence of sexual activity to substantiate other inferences, but it could not be “stand alone” evidence, solely for the purpose of denigrating the credibility of a witness on the basis of the “sexual nature of her past sexual activity” (s. 276.1; s. 276.2; s. 277). Parliament did push back against the Seaboyer majority by preserving its earlier preference that any such evidence would be presumptively excluded. The Bill’s preamble even indicated that Parliament expected sexual history evidence to only be “rarely” relevant at trial. To help ensure that rarity, the new rape shield imposed a strict admissibility process on the accused, who would need to first produce an affidavit containing the particular details of the sexual history evidence they wish to adduce, and only then would the trial judge decide to proceed to a voir dire. In other words, under C-49, the onus would be on the accused to establish the connection between sexual history of the complainant and the defence(s) they wished to advance. These provisions—and the legislative package itself—would be later upheld by the Supreme Court in their 2000 decision of R. v. Darrach.

Despite this revised rape shield, there is evidence to suggest that trial tactics reliant on rape myths were still finding their way into Canadian courtrooms. Indeed, instead of adopting the new rape shield’s intended exclusion of most sexual history evidence, some trial judges continued to apply Seaboyer as only allowing exclusion when the sexual history evidence directly fed into the “twin myths” (Craig Reference Craig2016a, 52). Given this interpretation, defence counsel continued to be regularly permitted to introduce evidence of sexual history for misleading purposes, because trial judges were often at a loss to establish a direct link between the twin myths and sexual history evidence in question. In fact, notwithstanding Parliament’s clear intention in Bill C-49 for sexual history evidence to be used in the rarest of cases, Meredith, Mohr and Cairns Way (Reference Meredith, Mohr and Way1997) found that applications for disclosure were still being made successfully in ten to twenty percent of cases.

Within three years of the new rape shield’s implementation, its constitutionality was again at issue at the Supreme Court. This time the challenge, in the case of O’Connor (1995), concerned the related issue of third-party records. Since the provisions in the Code did not specifically deal with third party-records (typically held by therapists and rape counsellors), the bench was faced with the novel question of whether defence lawyers could use that evidence (Hiebert Reference Hiebert2002, 107). A majority of the Court decided in favour of the criminally accused, holding that the Crown has a duty to disclose to the defence a sexual assault complainant’s therapeutic records where the defence’s right to a full trial and fair defence might otherwise be compromised (O’Connor, 417). The Court provided hypothetical examples where such evidence may be relevant to the defence, such as when they might contain information pertaining to the events underlying the alleged assault, or where it may contain information that bears on the credibility of the complainant (O’Connor, 441). However, there was significant disagreement between the majority and minority opinions on how best to govern the release of these records, including competing opinions on what the threshold for demonstrating likely relevance should be, and whether society’s interest in the reporting of sexual assault should be considered (Hiebert Reference Hiebert2002, 107–109). As a consequence of this decision, the rape shield’s second policy cycle concluded, leaving it to Parliament to modify the new common law, defendant-centred test with a new statutory framework that might better protect complainants.

Policy Cycle 3 The Enactment of Sections 278.1-278.91 (1997–2017)

With the decision in O’Connor, Parliament returned once again to the agenda-setting stage to draft expanded rape shield legislation. Like earlier policy cycles, this one would again focus on balancing constitutional rights. But, unlike prior cycles of policy, which focused primarily on Charter-proofing for due process, the new legislation, Bill 1996–97, C-46, was explicitly designed to emphasize the equality rights of sexual assault complainants. This policy cycle included an enhanced consultation process with a number of women’s groups emphasizing the equality rights of sexual assault complainants (Cameron Reference Cameron2001). These concerns were reflected in Parliament’s decision to enact almost word for word the constitutional test for third-party records that had been proposed by Justice L’Heureux-Dubé in her O’Connor dissent (Manfredi and Kelly Reference Manfredi and Kelly2001, 333–36; Baker Reference Baker2010, 22–26). In adopting L’Heureux-Dubé’s proposed complainant-focused approach, Parliament’s C-46 restricted the accused from accessing records “for which there is a reasonable expectation of privacy” and when they contain information that will only serve to “distort the search for truth” and have little probative value (Mills 1999, par. 99, par. 89). C-46 added section 278.5 into the Code, which contains a list of factors for judges to consider when deciding on likely relevance for disclosure of records, including the equality rights of men and women, and society’s interest in reporting sexual assault (Gotell Reference Gotell2002, 255). The bill specifically aimed to guide judicial discretion and to tip the balance in favour of the rights of sexual assault complainants, recognizing the implications that disclosure can have (Gotell Reference Gotell2002, 267).

Despite these consultative and legislative efforts, Lise Gotell’s (Reference Gotell2002) analysis of lower court decisions found that the courts continued to avoid giving weight to the equality rights of complainants when deciding on issues of disclosure (290). She also identified a common theme of judges resisting the conceptualization of sexual violence as systemic, and not simply the responsibility of individual actors, despite the language in section 278.5, which explicitly requires the judiciary to consider “society’s interest” (Gotell Reference Gotell2002, 283). Once again, the gains made in formal legislative recognition appeared to be undermined by practical implementation.

Bill 1996–97, C-46 was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court in Mills, but with an important caveat: “[When trial judges are] uncertain about whether [a record’s] production is necessary to make full answer and defence… the judge should rule in favour of inspecting the document. As L’Heureux-Dubé stated in O’Connor ‘in borderline cases, the judge should err on the side of production to the court.’ The interests of justice require nothing less” (Mills 1999, para. 132).

The majority’s interpretation thus nudged the test for disclosure under C-46 to privilege the due process rights of the defendant at the expense of the complainant’s equality rights. This judicial tweak to C-46’s implementation may have invited some of the very same defence tactics that Parliament intended to eliminate.

Evidence suggests that C-46 did not result in a real, tangible difference in the manner in which women continued to be mistreated in the courtroom (Johnson Reference Johnson and Sheehy2012, 614). Following the Mills decision, associations representing criminal lawyers formulated and popularized strategies to manipulate disclosure rules to work to the advantage of the accused. The Ontario Criminal Lawyers’ Association even held a “study day” to provide their members with advice on how to make successful applications for disclosure despite the enactment of section 278 (Gotell Reference Gotell2002, 272). In its newsletter, the Ontario Criminal Lawyers’ Association called on defence counsel to continue “being relentless” in reminding the courts that it is not in the interests of justice to ever deny any accused their due process rights (Gotell Reference Gotell2002, 272). While these organizations could be expected to be zealous in their advocacy of the criminally accused, their interventions pose obstacles to implementation that might have been anticipated in the legislative process (and mitigated as much as possible).

Despite the aims of legislators throughout this period, defence counsel continued to be permitted to introduce sexual history evidence for misleading purposes (Craig Reference Craig2016a, 51; Craig Reference Craig2018). Vandervort (Reference Vandervort and Sheehy2012) cites cases where trial judges allowed sexual history evidence—including a case involving the sexual assault of a twelve-year old girl (114–16). Craig (Reference Craig2016b) cites a case where defence counsel was permitted to cross-examine a sexual assault complainant at length about whether or not she was screaming while being forcefully penetrated (226). When the complainant indicated that she was not screaming, the defence asserted that “real victims fight back,” and that her lack of screaming demonstrated that the sexual assault would be better characterized as consensual sexual activity (Craig Reference Craig2016b, 226). Although cross examinations are an important feature of any criminal trial, Parliament clearly intended its legislative reforms to create a more humane process, recognizing the humiliation, trauma, and re-victimization that can occur throughout the trial process for complainants of sexual assault. Despite these complications in implementation, with courtroom actors not adhering to the rape shield assiduously, and with rape myths still very much in judicial discourse, the rape shield provisions continued to operate in this manner for nearly twenty years.

Policy Cycle 4: Bill C-51 (2017–Present)

The lengthy third policy cycle was finally punctuated by a series of high-profile cases that put the deficiencies of the rape shield in stark relief: Canadians were shocked by reports of trial judge Robin Camp’s rape-myth-infused, outrageous comments to a sexual assault complainant, including questioning why the complainant could not “just keep [her] knees together” to prevent the rape (R. v. Wagar 2014).Footnote 2 Or reports of judge Jean-Paul Braun’s suggestion that there are “degrees of consent” and that the seventeen-year-old complainant “flirted” with the accused and clearly “enjoyed getting attention from [him because] he looked good” (R. v. Figaro 2017; CBC News 2017). The Liberal government tabled Bill C-51, an omnibus bill, in June 2017, putting the rape shield back on the policy agenda and re-starting the policy cycle. The government emphasized that C-51 would ensure that victims of sexual assault are treated with the “utmost compassion and respect” by introducing provisions which “ensure that the law is as clear as it can be, in order to minimize the possibility of the law being misunderstood or applied improperly” (Marco Mendicino, House of Commons, Second Reading, June 6, Reference Mendicino2017). The government’s comments illustrate that C-51 was initially crafted with some awareness that the prior rape shield cycles had suffered in implementation.

The legislative changes were enacted in December 2018 and significantly altered the rape shield regime, adding sections 278.92–278.97 to the Code. The procedures governing the admissibility hearing for sexual history evidence now allowed complainants the formal right to appear at the proceedings, make submissions, and be represented by counsel (ss. 278.94(2)–278.94(3)). The amendments also required judges to consider “society’s interest in encouraging the obtaining of treatment by complainants of sexual offences,” when deciding on the admissibility of records in the possession of the accused (s. 278.92(3)). Any such record is deemed inadmissible unless the court determines that it “is relevant to an issue at trial and has significant probative value that is not substantially outweighed by the danger of prejudice to the proper administration of justice” (s. 278.92(2)(b)). This broad and subjective language of “relevant to an issue at trial” repeats the same textual flaw of earlier provisions. The same language (“relevant to an issue at trial”) also continues to be used with respect to evidence of sexual activity in s. 276, even though Parliament reframes it to specifically note (in s. 276(2)(a)) that the evidence of sexual activity cannot be adduced to support one of the “twin myths” inferences. (While this was always the clear meaning of the section, the revised and explicit wording is necessary to prevent trial judges from allowing the evidence if it was “relevant” and of “significant probative value” despite the fact that it might be for the purpose of supporting the impermissible inferences.) While much of C-51 aims at altering the behaviour of courtroom actors, the tightening up of the language still allows for a considerable amount of interpretive flexibility that might undermine the protection provided to sexual assault complainants.

Bill C-51 also expands the definition of “sexual activity” under section 276. The definition now includes “any communication made for a sexual purpose or whose content is of a sexual nature,” capturing emails, text messages, images and videos that form part of a communication, if made for a sexual purpose, or if its content is sexual in nature (s. 276(4)). The new legislation also emphasizes conscious consent (s. 2.73.1(2)). Bill C-51 also increased the notice period of third-party records applications and emphasized that notice must be provided to the Crown, complainants, record-holders, and other interested parties (s. 278.3(5)). Finally, C-51 also requires judges to provide reasons for their admissibility decisions (s. 278.94(4)(5)). However, a publication ban will cover all of the rape shield proceedings, including the decision and reasons for judgment (ss. 278.95(1)(2)).

Although the Bill’s provisions reflect the government’s concern for equality rights and the treatment of complainants, the Bill’s accompanying Charter statement reveals a continuing preoccupation with the due process rights of the accused (Charter Statement 2017). This is perhaps to be expected, given the nature of such statements, but the Charter statement for C-51 omits any discussion of other rights (of complainants, for example) to focus on the accused’s section 7 and section 11(d) rights. Through the statement, the government demonstrates that, in drafting the legislation, they were most cognizant of the due process rights of the accused and the importance of the provisions being consistent with Supreme Court jurisprudence.

Examining the C-51 Legislative Process

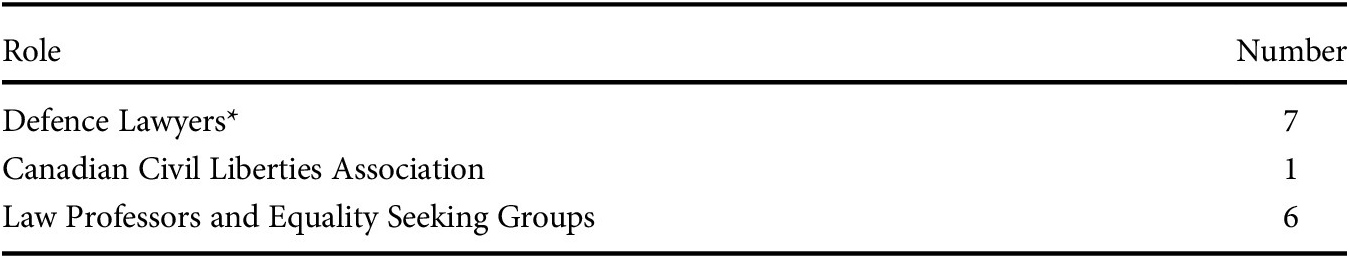

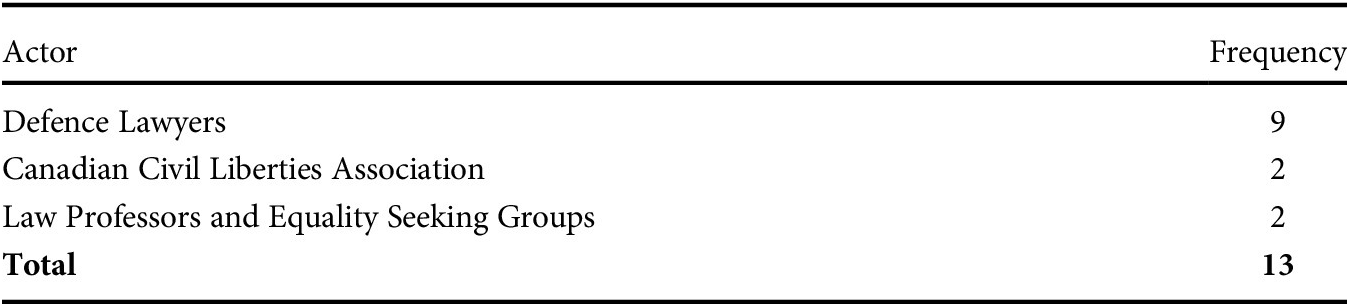

A careful examination of the legislative process of C-51 allows for an empirical assessment of which competing policy concerns were privileged or minimized, while also revealing whether Parliament understood this newest version of the rape shield as directly addressing the deficiencies of its preceding cycles. Our analyses reveal that while the debates in the House of Commons were largely superficial, particularly lacking discussion of potential implementation issues, the witnesses testifying to the Parliamentary committee offered extensive evidence of both practical implementation issues and constitutional challenges that C-51 could produce, as well as solutions to address them. However, most of the expert testimony at the committee continued to be framed as due process problems that C-51 might unintentionally create, with far less emphasis put on potential problems which could arise in the judicial implementation of the rape shield provisions. In order to demonstrate these tendencies in the legislative process, we conducted an in-depth qualitative and quantitative content analysis on the transcripts from the legislative proceedings of Bill C-51. This included consideration of the House of Commons debates and the witnesses’ testimony at the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights’ meetings in October and November 2017. We coded to identify statements indicative of knowledge of past implementation problems, both constitutional and practical, and to assess whether witnesses were “warning” Parliamentarians of potential implementation problems and whether they provided potential solutions or alternatives. Committee witnesses were categorized into groups based on their respective roles, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Breakdown of Committee Expert Witnesses

* All spoke as individuals except for Ms. Megan Savard, who represented the Criminal Lawyers’ Association

After an initial survey of the material, we identified signs of “implementation problems” being discussed to varying degrees by committee witnesses and Parliamentarians. Two implementation categories (“due process arguments” and “judicial implementation arguments”) were identified and quantitatively assessed by counting the number of times such arguments were mentioned. We define an “argument” as the raising of a conceptual idea such that an instance of the idea would be counted once even if several sentences related to that idea. The first concept “due process arguments” includes any testimony that explicitly mentions that the provisions may be “unconstitutional” or vulnerable to “Charter challenge” in the context of the accused’s protected rights, along with explicit mention of particular due process sections of the Charter that might be infringed, such as sections 7 and 11(d), or if it was suggested that the provisions might not pass a section 1 analysis. Implicit mention of due process defects is also included, such as phrases such as: “will result in the conviction of innocent people.” Explicit mention that the rape shield provisions will have the unintended consequence of adding to trial delay and court backlog are also included under the concept of “due process arguments,” with this concern likely stemming from the recent R. v. Jordan (2016) case.

The second category, labelled “Judicial Implementation Arguments,” consists of explicit mentions that judges have not and/or will not uphold the rape shield provisions as they are intended.Footnote 3 This encompasses explicit reference to past judicial mistakes, and a “judge’s ignorance or biases.” It also includes implicit comments on judicial behaviour through informal language, such as the following: “there is a lot of room for mistakes in understanding by judges.” This measure will help demonstrate whether Parliamentarians are being explicitly warned of potential problems in implementation (or, in the case of their own statements, aware of that potential).

House of Commons Debates

The debates in the House of Commons at each stage of legislative readings of Bill C-51 tended to be fairly superficial. Since Bill C-51 was an omnibus bill, the rape shield was not the sole topic for debate, and in fact, its amendments were largely overshadowed by other clauses, such as the one concerning the removal of “zombie provisions” in the Code. Footnote 4 Since the rape shield measures received all-party support, sharper comments were averred in favour of generic praise for the new legislation. In the few instances where implementation concerns were mentioned, C-51 was uncritically presented as the solution. New Democratic Party Member Wayne Stetski’s contribution is illustrative:

Too often, victims of sexual assault find themselves isolated by the courts. They have no one to protect them from aggressive questioning by a defence attorney and no one to be their advocate. Sometimes there are poorly trained judges, as we learned last year when a judge demanded of a victim why she could not just keep her knees together while she was sexually assaulted. (House of Commons, Second Reading, June 15, Reference Mendicino2017)

At all three readings in the House, Parliamentarians did not wrestle with the difficulty of altering the behaviour of judges and other courtroom actors. There is no evidence that they considered the inefficacy of simply introducing expanded rules of evidence and procedure. In general, the Parliamentary debates ignored the implementation problems from the prior policy cycles, and instead tacitly approved broad and subjective terms that have proved to be prone to judicial misapplication.

The House of Commons debates also gave short shrift to potential due process challenges the new provisions might create. One exception was Conservative MP Michael Cooper, who acknowledged that he had “serious concerns about the defence disclosure requirements” which “go to the heart of trial fairness” and “guard against wrongful convictions” (House of Commons, Third Reading, December 11, Reference Mendicino2017). After Cooper’s statement, the spectre of a constitutional challenge was not raised again. This is in stark contrast to the Parliamentary Committee hearings, where due process and judicial implementation issues were discussed much more robustly.

Committee Hearings

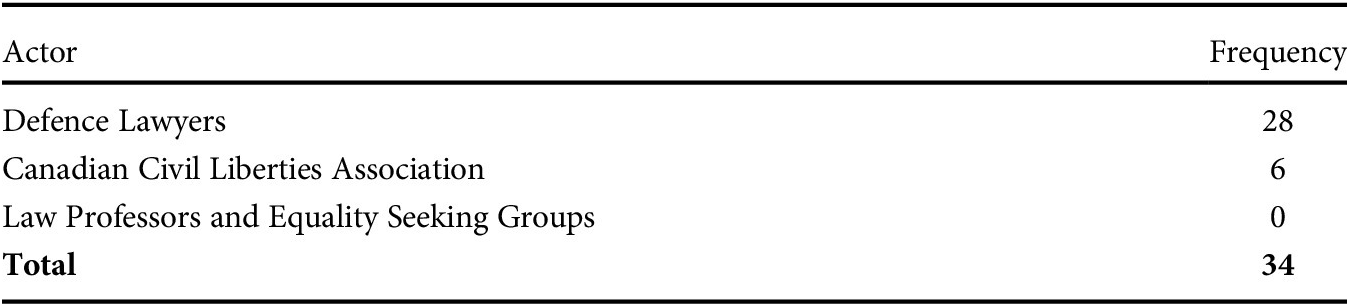

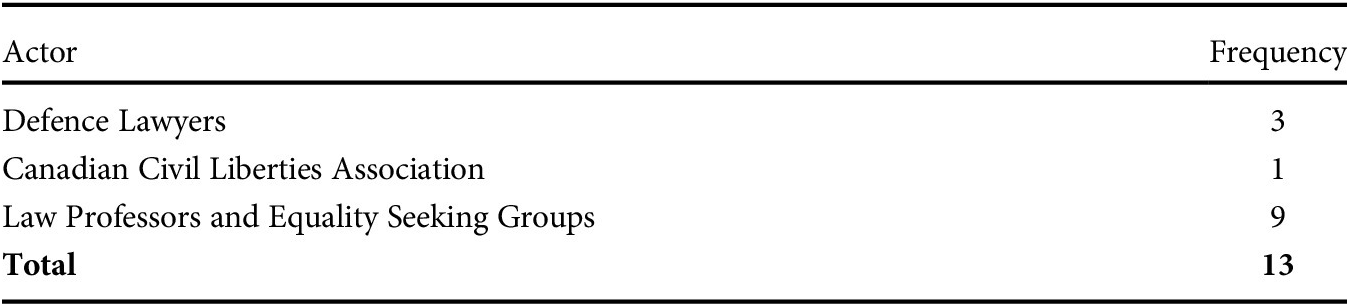

The hearings of the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights for Bill C-51 demonstrate the extent to which constitutional arguments pervade the framing of criminal justice policy problems. Over five days of testimony, witnesses explicitly and implicitly highlighted potential due process issues with the rape shield provisions of C-51 on thirty-four occasions (see Table 2). In contrast, issues which could arise in the judicial implementation of the rape shield were articulated on only thirteen occasions (see Table 3). Comments regarding constitutionality were exclusively made by defence lawyers and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA). In contrast, issues with judicial conduct were made by a wider variety of witnesses, but disproportionately emphasized by law professors and equality seeking groups. Potential solutions for implementation problems were proposed by witnesses on thirteen occasions (see Table 4).

Table 2 Frequency of Due Process Arguments

Table 3 Frequency of Judicial Implementation Arguments

Table 4 Frequency of Solutions Proposed

Due Process Arguments

Due process arguments were frequently made during the hearings. Many of the witnesses made explicit references to unconstitutionality. Others made implicit references by invoking constitutional doctrines and terminology, such as the “principles of fundamental justice.” Several instances are illustrative of the due process warnings given to the Committee:

Ms. Megan Savard (Lawyer, Criminal Lawyers’ Association): I can’t promise I wouldn’t bring a constitutional challenge. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Savard2017, Meeting 71)

Mr. Michael Spratt (Criminal Defence Lawyer, Abergel Goldstein and Partners, As an Individual): This change also impacts the right to a full answer and defence in a fair trial. It undermines the process of cross-examination, which is a crucible for the discovery of truth. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Spratt2017, Meeting 71)

Ms. Breese Davies (Criminal Defence Lawyer): I… think there would be a real concern on constitutional grounds about there being no rational connection between the stated purpose [of the rape shield provisions] and that language, and that it wouldn’t survive a minimal impairment analysis. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Davies2017, Meeting 71)

Ms. Laurelly Dale (Criminal Defence Lawyer: If [the rape shield provisions are] accepted, the balance of the trial will be entirely upset. Charter violations will occur, and it will ultimately result in the conviction of innocent people. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 25, Reference Dale2017, Meeting 72)

Judicial Implementation Arguments

Only thirteen times did witnesses mention the potential implementation problem of judges not assiduously following the proposed amendments. Although these comments did not dominate the hearings like the due process arguments, they are important because it proves that Parliamentarians, or at least the Committee Members, were made aware of the potential problem of judicial implementation. Some witnesses argued that legislation is insufficient without measures to improve compliance:

Ms. Christine Silverberg: In my view, a significant failure in enforcing sanctions against sexual assault is not a failure of the law. Rather, the failure is in the capacities of, implementation by, and performance standards of both the police and prosecutorial branches, and dare I say, the lack of particular knowledge and training of the judiciary. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Silverberg2017, Meeting 71)

The doubt that judges will scrupulously follow the proposed amendments in Bill C-51 was clearly expressed by Cara Zwibel, the Acting General Counsel for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, who was opposed in general to the rape shield and disclosure amendments: “In our view, the government should be focusing on other ways of protecting and respecting complainants rather than amending what is already a progressive and protective law. The flaw may be in the application rather than in the text itself” (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 30, Reference Zwibel2017, Meeting 73).

Some legal scholars who participated in the hearings pointed to specific sections of the rape shield and disclosure regime that judges have struggled to properly apply in the past. Law professor Janine Benedet emphasized that, under the current regime, judges are struggling to interpret the exclusionary rules of evidence in sexual assault cases, and that there are divided opinions on what the case law indicates. She stated:

…That would actually be an important and useful clarification, as is the following proviso, which is that, if the evidence is being adduced to support one of the twin myths, it is simply not admissible and we don’t go on to a balancing exercise. Those are both areas in which I see courts struggling to apply these provisions as consistent with their original intent, and they remain important clarifications and additions to the sexual history provisions in that area. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 25, Reference Benedet2017, Meeting 72, emphasis added)

Professor Elizabeth Sheehy agreed that judges have struggled to properly interpret aspects of sexual assault law, and supports the bill as better than the status quo: “Of course I share your concern that we have persistent problems in terms of judges fumbling the ball on the legal rules regarding consent and other issues in a sexual assault trial. I guess I still favour further legislative clarification and codification when possible” (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 25, Reference Sheehy2017, Meeting 72, emphasis added).

Overall, witnesses only made mention of judicial implementation issues thirteen times, but they are significant because they demonstrate how informed Parliament was of potential challenges in implementation.

Solutions Proposed

Witnesses also made thirteen mentions of proposed modifications to improve the bill. These improvements included ways to mitigate constitutional challenges, as well as alternative means to achieve the objectives of the bill, and measures that could be concurrently implemented to support the success of the bill. Many of the “Charter-compliant solutions” included narrowing of the legislation, for example: “Ms. Megan Savard: My submission suggests that it should be restricted to scenarios where the defence intends to introduce the record itself into evidence. Anything further is… an overbroad reach that goes beyond protecting complainants or protecting privacy interests” (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Savard2017, Meeting 71).

Similar to narrowing the scope of the legislation, some suggestions entailed making the legislation more clearly defined, such as in the following statement:

Mr. Michael Spratt: Above and beyond that, I think there needs to be some definition about what we mean when we say a “record” that there’s some privacy interest in. Unless you want to leave it to the Supreme Court or to judges to make that law for you, I think it might be good to demarcate exactly what we’re talking about… There’s a lack of specificity there that makes it, I think, very dangerous. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Spratt2017, Meeting 71)

Spratt warned Parliament that if they do not clearly define fundamental terms in the legislation, such as “record,” it will leave courts to “define it for [them],” essentially inviting more judicial discretion on matters where there may already be too much.

Some witnesses suggested alternative means to better achieve the policy goals of the rape shield and disclosure provisions of Bill C-51 for example:

Ms. Megan Savard: If you educate us, allocate funding to make sure we know what the rules are and set those rules out in the Criminal Code. That will go a long way to preserving the goals that you stated are the objectives of the bill without removing the flexibility that we need as defence lawyers to stop trials from grinding to a halt in the middle of the evidence. (Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 23, Reference Savard2017, Meeting 71, emphasis added)

One of the witnesses representing the Barbara Schlifer Commemorative Clinic spoke about judges misapplying the rape shield in the past and put forward a solution for Bill C-51 to be more successful in this aspect of implementation:

Ms. Amanda Dale: We mentioned accountability mechanisms at the beginning. We believe that in order to realize the potential of Bill C-51, the government must put in place some regularized provisions to ensure that the amendments have their intended effect. The clinic recommends that the government establish a community consultation process with front-line agencies and survivors to monitor the rollout. (Committee on Justice and Human Rights, October 25, Reference Dale2017, Meeting 72)

Underlying Dale’s comment is recognition of the potential for failure at the policy implementation stage if there is no enforcement mechanism to ensure that judges are following the provisions exactly as intended by Parliament. Despite thirteen mentions of some form of “solution” provided by witnesses to Parliament, with respect to the rape shield and disclosure provisions of Bill C-51, none of the recommendations were adopted.

The Rape Shield’s Problematic Policy Cycle

The attention we have given to the thirteen mentions of solutions and alternatives and the thirteen arguments about problems with judicial implementation should not be understood as reflecting the overall tenor of the Committee process. As described in the tables above, more than twice as many mentions were made concerning potential due process problems. While the other mentions demonstrate that implementation problems were in fact raised during the Parliamentary process, they were diluted in the larger context of constitutional deficiencies the new provisions might have from the perspective of the accused. To the extent that the due process framing of the policy continues to dominate the legislative process, the experience of the past policy cycles is unlearned. In particular, the problems that arise in judicial implementation of the provisions are not being adequately addressed, suggesting that the same problems of judicial misapplication of the rape shield will likely persist under the new regime.

Under the policy cycle framework, policy should improve each time it progresses through a rotation, if it is effectively taking advantage of the “feedback” received at the evaluation stage. Yet, our analysis reveals that the rape shield policy cycle gives disproportionate weight to due process concerns, underemphasizes the implementation challenges introduced by courtroom actors, and fails to allow for the revision of legislation, even when implementation difficulties are raised. Each of these aspects of the process will be discussed in turn.

The tendency to disproportionately fixate on the due process rights of the accused is symptomatic of a larger trend towards what has been described as the “judicialization of politics.” This term, as developed by Canadian and American scholars such as Peter Russell (Reference Russell1983, Reference Russell1994) and Mark Tushnet (Reference Tushnet1999), describes how socio-political issues are increasingly resolved in the courtroom rather than the legislature. Tushnet (Reference Tushnet1999) calls the consequence of this the “judicial overhang”: the prospect of judicial review distorts legislative deliberation since legislators try to anticipate how judges will act. The material impact of judicialization is not simply as benign as legislatures being more conscious of due process concerns and deliberately incorporating them within the policy design stage. Instead, the policy process has adopted a discourse of constitutional rights, in which the language and norms of due process have permeated how political actors engage with public issues, particularly ones concerning criminal justice (Russell Reference Russell1994, 173; Glendon Reference Glendon1991). This, in turn, transforms contentious social issues and questions of political justice into battlegrounds of rights, communicated and debated through the technical language of the law (Russell Reference Russell1983, 52).

In this “judicialized” context, C-51 and the preceding rape shield policy cycles are framed as pitting due process rights of the accused against the equality rights of sexual assault complainants. It cannot be doubted that the due process concerns are warranted, with the spectre of wrongful convictions rightfully in mind, but the extent to which these concerns garner attention tends to sideline other policy considerations and leaves the deliberations lopsided. In each cycle, even as Parliament has claimed to be engaging in a meticulous balancing exercise to ensure that the rape shield simultaneously protects due process rights and the equality rights of women, the legislative process skews towards a more hierarchical battle where rights are in conflict with one another and compete to be prioritized. Here, legal forms might dictate legislative outcomes: the constitutional challenge is much more likely to come from an aggrieved accused (in the form of an appeal from a criminal conviction) than from an equality claim made by a complainant. A risk-averse legislator seeking to “Charter-proof” their legislation, even if fully committed to advancing equality rights, is likely to have their attention drawn more towards the due process deficiencies that may result in an embarrassing and counter-productive constitutional invalidation.

This imbalance has contributed to a legislative policy cycle that has improved the “Charter-proofing” of the rape shield, but at the expense of crowding out other important policy concerns, such as those that address judicial implementation. In the House of Commons debates for C-51, Parliamentarians gave little consideration to whether changes to trial and evidence procedure were the best vehicle to change the behaviours of judges or counsel. Nor did Parliamentarians discuss broader alternatives to alter judicial behaviour and the culture of the courtroom. Parliamentarians might have considered solutions such as enhancing and increasing financial support to rape crisis centres and other organizations aimed at supporting and informing sexual assault complainants about the judicial process and even providing resources to advocate for complainants in admissibility hearings. As recommended at the Committee stage, the Government could establish a community consultative process that could help monitor the efficacy of the legislative changes and perhaps even employ “courtroom observers” to perform a similar task—the prospect of additional accountability measures might alter courtroom behaviour. Alternatively, and perhaps most controversially, some form of enhanced judicial training might be considered. We do not offer any of these alternatives as a panacea to what everyone agrees is a vexing and persistent problem, but merely to note their existence and suggest they deserve more consideration. In this regard, their low visibility in the Parliamentary discourse is discouraging. Instead of exploring alternatives, Parliamentarians implicitly accept that adding more technical restrictions and expanded evidentiary protections for complainants is the effective policy response.

The focus on technical legal changes is not surprising. Enacting such legislation is much easier than developing policy instruments to directly influence behaviour, such as legislatively mandated judicial training. Measures that seek to alter behaviour directly are difficult because they may implicate other constitutional norms, including the principle of judicial independence. In spite of those obstacles, there has been some recent movement towards the possibility of greater judicial training. In February 2017, Rona Ambrose (CPC) introduced Private Member’s Bill C-337 mandating judicial training on sexual assault law. In February of 2020, the Liberal Government offered its own legislation regarding judicial training, whose progression through the committee stage was halted by the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 5 This new approach was supported in principle by the leading expert on Canadian sexual assault trials, Elaine Craig, in addition to other legal scholars such as Jennifer Koshan and Carissima Mathen.Footnote 6 Craig highlighted that judicial training is necessary since judges are often appointed without any professional experience in this area, despite sexual assault law being particularly complex terrain.Footnote 7 A “profound lack of public confidence” in the “justice system’s handling of these particular cases” was also used to justify the need to change the judiciary’s conduct, and the role of judges as “gatekeepers” of the justice system warrants their specific training (Koshan Reference Koshan2017). Despite these articulated benefits of legislating judicial education, Bill C-337 remained unpassed for over two years, in part because of ongoing concerns about the Bill’s constitutionality, eventually dying in the Senate upon the dissolution of Parliament.Footnote 8

Mandated judicial training remains controversial. Representatives of the National Judicial Institute (NJI) and Canadian Judicial Council noted at the C-337 hearings that having “the executive branch dictating what exactly judges should do to maintain their professional skills, what areas of the law or other social context education they should or should not take” would violate the independence of the judiciary (Sabourin Reference Sabourin2017). Federalism also poses an obstacle since the NJI estimates 95% of sexual assault cases are heard in provincial courts and federal legislation would only impose training on federally-appointed judges (Kent Reference Kent2017). The Deputy Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs also emphasized practical difficulties with implementing judicial training, asking who would implement this training and whether the training would create delays in appointing judges (Giroux Reference Giroux2017). These difficulties invite governments to reach for easier-to-pass procedural and technical changes to the rape shield, in the misguided hope that such changes will at last influence judicial behaviour indirectly.

Finally, we observe that institutional and structural obstacles built into the legislative process contribute to the rape shield’s defective policy cycle. Current parliamentary practice is to require a bill to be “approved in principle” before it even arrives at the Committee, meaning that Parliamentarians endorse a bill’s essential form before expert evidence is presented to the Committees. Despite all of the implementation arguments and solutions offered, none of the recommendations were adopted by Parliament, and the rape shield and disclosure provisions of Bill C-51 were passed exactly as introduced. While the openness of the parliamentary process at the Committee stage, with a diverse group of defence lawyers, interest groups, activists, and academics, is surely commendable, the lack of a real opportunity to see that input result in changes to the legislation effectively devalues those contributions.

Another structural constraint—party discipline—also negatively impacts lessons learned from the policy cycle. In general, party discipline severely restricts Members of Parliament from engaging in genuine political debate over legislative matters (Aucoin and Turnbull Reference Aucoin and Turnbull2003, 429), and this is especially significant with the high-profile and sensitive matters of sexual assault legislation. Party discipline creates a disincentive for Parliamentarians to candidly acknowledge in the legislative process any mistakes or deficiencies of their own party’s prior or current policy initiatives, impeding the effectiveness of the evaluation and design stages. This is perhaps the most obvious explanation for why the solutions offered in Committee testimony were not seriously pursued.

The importance of the rape shield cannot be overstated. In Canada it is estimated that one in three women will be sexually assaulted in their adult life (Johnson Reference Johnson and Sheehy2012, 613). While the vast majority of these cases go unreported, those complainants who proceed through the criminal justice process deserve, at the very least, humane treatment. The trial process can unnecessarily demean victims, subjecting them to humiliation, trauma, and re-victimization, and both judges and policymakers can and ought to do better. While the impetus for introducing rape shield legislation is to protect the equality and privacy rights of sexual assault complainants, our study demonstrates that the legislative process of these “policy cycles” focuses disproportionately on remedying due process concerns, at the expense of considering the problems that arise in judicial implementation of the provisions. It is at least partly for this reason that the rape shield is largely suspended in a state of stagnation, where despite decades of policy reform, rape myths and trial tactics reliant on sexist assumptions are still being permitted in the courtroom and are likely to persist with the enactment of C-51.