Introduction

As business environments have become more dynamic, complex, and unpredictable, there is a pressing need for employees to shift from passively follow the narrowly defined work-related instructions to actively identify opportunities and threats in the workplace (Bindl, Parker, Totterdell, & Hagger-Johnson, Reference Bindl, Parker, Totterdell and Hagger-Johnson2012; Frese & Fay, Reference Frese and Fay2001). Proactive behavior refers to individuals' self-initiated efforts aiming to change and improve the work environment or oneself before problems emerge (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010; Parker, Williams, & Turner, Reference Parker, Williams and Turner2006). It transcends the boundaries of job requirements and becomes increasingly important to the effectiveness and success of contemporary organizations (Parker, Williams, & Turner, Reference Parker, Williams and Turner2006). Recognizing the crucial role of proactive behavior, researchers on strategic human resource management (SHRM) fields claimed that high-performance work systems (HPWS), an integrated system of human resource (HR) practices (Lepak, Liao, Chung, & Harden, Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006), are a powerful means to facilitate proactivity (Agarwal & Farndale, Reference Agarwal and Farndale2017; Beltrán-Martín, Bou-Llusar, Roca-Puig, & Escrig-Tena, Reference Beltrán-Martín, Bou-Llusar, Roca-Puig and Escrig-Tena2017), since they can effectively enhance employees' ability, successfully stimulate their motivation, and even provide them with more opportunities (Jiang, Lepak, Hu, & Baer, Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012; Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006).

While the extant literature offers insights into the importance of HPWS in fostering proactive behavior, several research gaps still need to be filled. First, prior studies have mainly concentrated on a single motivational state (e.g., psychological safety, intrinsic motivation, and role breadth self-efficacy) as mediators in the HPWS-proactivity chain (Agarwal & Farndale, Reference Agarwal and Farndale2017; Andreeva & Sergeeva, Reference Andreeva and Sergeeva2016; Beltrán-Martín et al., Reference Beltrán-Martín, Bou-Llusar, Roca-Puig and Escrig-Tena2017). However, these studies failed to consider that proactive behavior is essentially driven by multi-motivational pathways (i.e., can do, reason to, energized to) (Cai, Parker, Chen, & Lam, Reference Cai, Parker, Chen and Lam2019; Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010) and the latter two states might have a more long-term and universal impact on such behavior (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010). Work engagement is a multi-motivational state defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá and Bakker2002). Research has indicated that engaged workforce not only have a propensity to complete their tasks in a strong intrinsic motivation (i.e., reason to) (Salanova & Schaufeli, Reference Salanova and Schaufeli2008) but also are more likely to feel energetic and enthusiastic to behave proactively (i.e., energized to) (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Parker, Chen and Lam2019; Parker & Griffin, Reference Parker and Griffin2011). Moreover, given the energy-consuming nature of proactive behavior (Fay & Hüttges, Reference Fay and Hüttges2017; Ouyang, Cheng, Lam, & Parker, Reference Ouyang, Cheng, Lam and Parker2019; Wu & Parker, Reference Wu and Parker2017), engaged employees who feel more energetic and enthusiastic about their work are more prone to behave proactively. Taken together, this study intends to introduce work engagement as the mediator to provide a more comprehensive and plausible insight into how HPWS are related to proactive behavior.

Second, although recent research has noticed that front-line managers can be served as a contingency in the relationship between HPWS and individual outcomes, their focus has centered mainly on leader-domain perspective (e.g., empowering/charismatic leadership: Chuang, Jackson, & Jiang, Reference Chuang, Jackson and Jiang2016; McClean & Collins, Reference McClean and Collins2019), with less attention given to the relationship-domain perspective, that is, leader-member exchange relationship (LMX) (i.e., dyadic relationships that the immediate supervisors develop with their followers; Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). Given that the relationship between the employees and their supervisors may directly affect the implementation effect of the HR practices (Purcell & Hutchinson, Reference Purcell and Hutchinson2007), Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2019) proposed that LMX can act as a boundary condition for the effects of developmental HR practices on work engagement. However, compared to Fletcher's (Reference Fletcher2019) research emphasizing solely on a single HR practice, HR systems (e.g., HPWS) have more advantages in improving performance outcomes since a set of practices can produce synergistic effects to effectively encourage employees to present specific psychological states and behaviors (Beltrán-Martín et al., Reference Beltrán-Martín, Bou-Llusar, Roca-Puig and Escrig-Tena2017; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012; Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006). Thus, this study focuses on HR systems rather than an individual HR practice, and further investigates how LMX quality moderates the link between HPWS and proactive behavior via work engagement.

Finally, many scholars note that work engagement is resource-driven (Salanova & Schaufeli, Reference Salanova and Schaufeli2008; Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004) and use the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model to elucidate how various resources, such as personal resources (e.g., self-efficacy), organizational resources (e.g., HR practices), and social resources (e.g., LMX), can enhance levels of engagement separately (Breevaart, Bakker, Demerouti, & van den Heuvel, Reference Breevaart, Bakker, Demerouti and van den Heuvel2015; Cooke, Cooper, Bartram, Wang, & Mei, Reference Cooke, Cooper, Bartram, Wang and Mei2019; Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, Reference Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti and Schaufeli2007). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that more resources are not necessarily better; in fact some resources can complement and replace each other (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Hobfoll, Freedy, Lane, & Geller, Reference Hobfoll, Freedy, Lane and Geller1990). Hence, the present study proposes that subordinates with high-quality LMX will depend less on HPWS and vice versa. We believe this approach can broaden our horizon and provide an alternative perspective to understand how line managers and the HR systems coordinate and cooperate with one another.

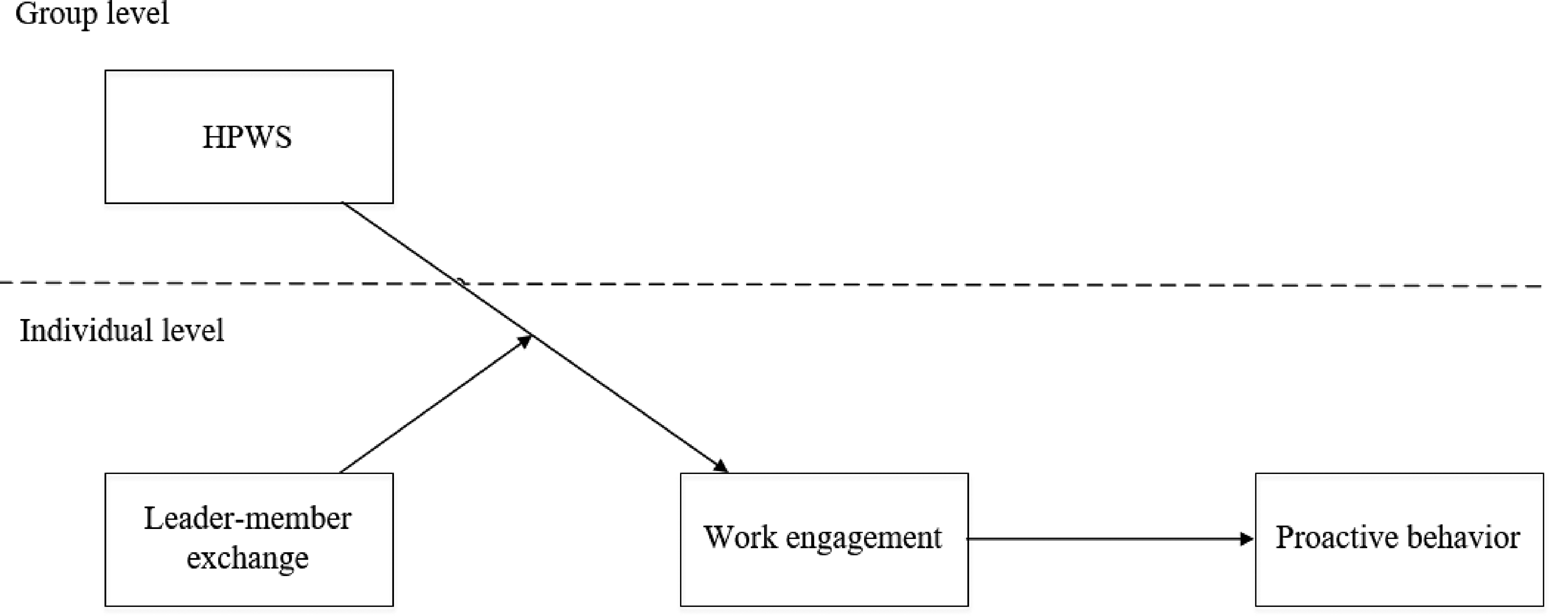

Taken together, the present research contributes to the existing literature in three major ways. First, by integrating the JD-R model and conservation of resources (COR) theory, we investigate the mediating mechanism of how and why HPWS can fuel the proactive fire. As work engagement contains two motivational states (‘reason to’ and ‘energized to’), our study contributes to unlocking the black box between HPWS and proactive behavior in a more comprehensive and concise way. Second, this study extends the work of Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2019) by examining LMX as a boundary condition for the effects of HR systems. We not only use a system perspective to further advance our understanding of how the LMX and HPWS coordinate, but also directly echo the call for research in SHRM to further consider the role of line managers (Steffensen, Ellen, Wang, & Ferris, Reference Steffensen, Ellen, Wang and Ferris2019). Finally, contrary to prior studies (e.g., Audenaert, Vanderstraeten, & Buyens, Reference Audenaert, Vanderstraeten and Buyens2017; Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2019) which mainly regard HR and LMX as synergistic partners, the present study uses the COR theory as our basis, and reveals that the high-quality LMX may directly substitute HPWS. Although extant research has used the viewpoint of resource substitution by Hobfoll and Leiberman (Reference Hobfoll and Leiberman1987) to infer the joint effect of other resources (e.g., managerial practices) and personal resources (e.g., task proficiency) on individual outcomes (Boon & Kalshoven, Reference Boon and Kalshoven2014; Shantz, Alfes, & Latham, Reference Shantz, Alfes and Latham2016), only a few empirical studies have attempted to examine the LMX itself as an important social resource that may work together with the organizational resources (e.g., HR systems). Our study fills this void and further enriches the substitute hypothesis of the COR theory in the field of SHRM. The theoretical model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical model.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

The impact of HPWS on work engagement

HPWS refers to a group of separate but interconnected HR practices designed to enhance employees' knowledge, skills, and abilities (Huselid, Reference Huselid1995; Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006), and to ensure that an organization can obtain sustainable competitive advantages (Huselid, Reference Huselid1995). Following this vein, early studies of SHRM mainly used organization as the level of analysis to explore the relationship between intended HR practices (HR policies initially designed by the senior management to achieve the organization's business strategy; Wright & Nishii, Reference Wright and Nishii2007) and organizational outcomes (Huselid, Reference Huselid1995; Jeong & Choi, Reference Jeong and Choi2016). However, considering that the implementation of specific HR practices may vary across different functional groups/departments in a company (Lepak & Snell, Reference Lepak and Snell1999, Reference Lepak and Snell2002; Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006), recent scholars in this field turned their attention toward actual HR practices (HR programs and processes that are actually implemented by the line managers of different job groups/departments; Wright & Nishii, Reference Wright and Nishii2007) and further examined their effect on performance outcomes at the individual and group levels (Den Hartog, Boon, Verburg, & Croon, Reference Den Hartog, Boon, Verburg and & Croon2013; Lee, Pak, Kim, & Li, Reference Lee, Pak, Kim and Li2019). In fact, numerous researchers have also proposed that it is the HR practices actually enforced in the group/department, rather than the intended HR policies, that are likely to be more tangible and direct preconditions for employees' work attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Huselid & Becker, Reference Huselid and Becker2000; Purcell & Hutchinson, Reference Purcell and Hutchinson2007). Therefore, the present study focuses on the HPWS that are actually implemented in the group and their relationship with work engagement.

Although operational definitions of ‘work engagement’ are often inconsistent across researchers (e.g., Harter, Schmidt & Hayes, Reference Harter, Schmidt and Hayes2002; May, Gilson, & Harter, Reference May, Gilson and Harter2004; Rich, Lepine, & Crawford, Reference Rich, Lepine and Crawford2010; Saks, Reference Saks2006; Schaufeli et al., Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá and Bakker2002), Schaufeli et al.'s (Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá and Bakker2002) conceptualization of work engagement as a ‘positive, fulfilling, work-related, affective-cognitive state characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption’ remains the most widely used and validated measure in different countries and occupations (Salanova & Schaufeli, Reference Salanova and Schaufeli2008; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006). Vigor is characterized by putting a great deal of energy into their work and the willingness to persist even in the face of barriers and setbacks. Dedication represents a strong involvement toward one's work, and experiencing positive affects, such as pride, enthusiasm, and challenge. While dedication and job involvement seem to share some conceptual space, the former is a broader, more inclusive construct. This is because job involvement simply refers to a cognitive state about the degree to which an individual psychologically identifies with his or her job (Kanungo, Reference Kanungo1982), whereas dedication encompasses not only a cognitive judgment, but also an affective connection with one's tasks (e.g., enthusiasm) (Schaufeli et al., Reference Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá and Bakker2002). In line with this, numerous scholars (e.g., Rich, Lepine, & Crawford, Reference Rich, Lepine and Crawford2010; Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, Reference Salanova, Agut and Peiró2005) have emphasized that job involvement can be understood as a facet of dedication, rather than being equivalent to dedication, and even less as work engagement. Finally, absorption is characterized by high levels of concentration and immersion while working, whereby time appears to fly and one has difficulty detaching from work.

Previous research has revealed that resources are a necessary prerequisite for employees to be engaged in their work (Bakker, Demerouti, & Sanz-Vergel, Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Sanz-Vergel2014; Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004), and unravels its formation through the lens of JD-R theory (Bakker, Demerouti, & Sanz-Vergel, Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Sanz-Vergel2014; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001). In the JD-R model, job resource refers to aspects of the job (physical, social, or organizational), that not only help employees cope with job demands (e.g., workload), but more importantly, contribute to achieve work goals and stimulate personal growth, learning, and development (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007). In this light, HPWS can be categorized as a valuable job resource at the organizational level (Boon & Kalshoven, Reference Boon and Kalshoven2014; Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2021; Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Cooper, Bartram, Wang and Mei2019), since HPWS practices enable employees to become more proficient at their tasks (e.g., extensive training), and provide opportunities for them to climb the career ladder (e.g., internal promotion) (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012).

According to the motivational process underlying the JD-R theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007), resources trigger a motivational potential to facilitate high levels of work engagement through both intrinsic motivation (i.e., satisfy employees' needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence) (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000) and extrinsic motivation (i.e., help employees accomplish work goals) (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007). Following this vein, HPWS as an organizational resource (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2021) can intrinsically and extrinsically motivate employees to be fully engaged at work. More specifically, rigorous selection and extensive training can effectively improve the domain skills and knowledge, thus enabling employees to perform well (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012; Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006). Empowerment and participation encourage employees to use their discretion to carry out tasks, which simultaneously nurtures their capabilities and satisfies their need for autonomy (Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006). Information sharing and performance appraisal enable employees to better understand work goals and increase the likelihood of accomplishing them (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012; Maden, Reference Maden2015). Thus, the more resources employees receive from HPWS, the more motivated they will be to demonstrate greater levels of enthusiasm and energy.

Hypothesis 1. HPWS are positively associated with work engagement.

Work engagement and proactive behavior

Proactive behavior is a self-initiated action that focuses on reshaping employees or working circumstances to achieve a different future (Crant, Reference Crant2000; Parker, Williams, & Turner, Reference Parker, Williams and Turner2006). In the current investigation, we propose that work engagement is positively related to proactive behavior for several reasons. First, individuals with high levels of vigor are more ‘energized to’ put extra effort into proactive behavior, which is always beyond typical task requirements (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010). Second, dedicated employees possess positive emotions (Bindl et al., Reference Bindl, Parker, Totterdell and Hagger-Johnson2012; Maden, Reference Maden2015) and are enthusiastic to strive for proactive goals, despite potential obstacles and setbacks that may occur in this process. Third, to identify existing problems in the workplace and seize opportunities for future-oriented changes, it is necessary for employees to fully absorb and engage in their work.

Besides, while proactive behavior can contribute to a variety of performance outcomes (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010), some researchers have argued that challenging the status quo may also incur misunderstanding and resistance from leaders and colleagues (Frese & Fay, Reference Frese and Fay2001; Wu & Parker, Reference Wu and Parker2017); therefore, individuals need a strong ‘reason to’ perform this risk-taking behavior (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010). In order to delicately describe the motivational process (i.e., reason to) behind such behavior, we use the COR theory to explain the above-mentioned relationships. The gain spiral outlined in COR theory focuses on the dynamic transfer of resources and proposes that people with strong resource pools are less fearful of resource loss and are more willing to take risks to win additional resources (Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl, & Westman, Reference Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl and Westman2014; Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001). As a result, when employees are highly engaged in their work, they have more resources available (Boon & Kalshoven, Reference Boon and Kalshoven2014) and are more inclined to be proactive in executing the behaviors desired by the organization, even though it may be offending to others (Frese & Fay, Reference Frese and Fay2001; Parker & Collins, Reference Parker and Collins2010). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2. Work engagement is positively related to proactive behavior.

The mediating role of work engagement

Integrating the above theories (i.e., JD-R theory and COR theory) and hypotheses, we contend that work engagement plays a mediating role in the relationship between HPWS and proactive behavior. As noted above, HPWS, as a resource provision system, are expected to promote workforce engagement since they not only can provide subordinates with ample opportunities for growth and development (intrinsic motivation) (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012), but also can fully equip employees with sufficient expertise and skills to better accomplish their work goals (extrinsic motivation) (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lepak, Hu and Baer2012). In turn, energetic and well-resourced employees are more willing to behave proactively, because they are motivated to devote additional effort and enthusiasm to identifying and solving problems, and more importantly, they are eager to reinvest resources to improve the work situation, without fear of the potential risk. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. Work engagement mediates the relationship between HPWS and proactive behavior.

The moderating role of LMX

In addition to organizational resources, employees could also gain crucial resources from their supervisors. Given that leaders develop different quality relationships (ranging from low to high) with their followers (i.e., LMX; Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995; Sparrowe & Liden, Reference Sparrowe and Liden1997), the leadership resources available to subordinates will vary. Employees with low-quality LMX are limited to fulfilling obligations stipulated in their employment contracts, and are therefore likely to be assigned mundane tasks, receive relatively little supervisory support and promotion opportunities (Graen & Scandura, Reference Graen and Scandura1987; Liden & Maslyn, Reference Liden and Maslyn1998). In contrast, in high-quality relationships, employees will obtain extensive social-emotional support, more valuable information or meaningful assignments (Xia, Schyns, & Zhang, Reference Xia, Schyns and Zhang2020), since high-quality LMX relationships are characterized by mutual trust, obligations, and respect (Graen & Scandura, Reference Graen and Scandura1987; Liden & Maslyn, Reference Liden and Maslyn1998). Consequently, high-LMX subordinates can obtain abundant leadership resources (Lebrón, Tabak, Shkoler, & Rabenu, Reference Lebrón, Tabak, Shkoler and Rabenu2018; Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari, & Isaksson, Reference Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari and Isaksson2017), which play either an intrinsic or extrinsic motivational role in fostering work engagement (Agarwal, Datta, Blake-Beard, & Bhargava, Reference Agarwal, Datta, Blake-Beard and Bhargava2012; Breevaart et al., Reference Breevaart, Bakker, Demerouti and van den Heuvel2015; Lebrón et al., Reference Lebrón, Tabak, Shkoler and Rabenu2018).

COR theory argues that resources dedicated to meeting the same goal can be substituted for one another (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Freedy, Lane and Geller1990). In this vein, although HPWS and high-quality LMX individually could both create a high level of engagement, these two kinds of resources may also substitute for each other. More specifically, employees with high-quality LMX are likely to receive more guidance and emotional support as well as have an advantage in future resource gain (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989). In this case, subordinates tend to prioritize using leadership resources (i.e., LMX) rather than organizational resources (i.e., HPWS), since the former are more proximal and direct (Chuang, Jackson, & Jiang, Reference Chuang, Jackson and Jiang2016). As a result, high LMX employees are less likely to capture resources by focusing on management policies and practices, thereby, neutralizing the role of HPWS in promoting engaged workforce. Whereas, in low-quality LMX relationships, the positive impact of HPWS on work engagement may be amplified. Hobfoll (Reference Hobfoll2001) theorized that resources would have a more salient potential motivational effect on employees with less resources, since these people are more likely to face the pressure of resource loss and are more sensitive to any access to resources. According to this view, employees in low-quality LMX can only receive minimal assistance and feedback from their supervisor (Sparrowe & Liden, Reference Sparrowe and Liden1997); thus, their resources are rather limited and are more at risk of experiencing resource loss as well as psychological stress (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). To alleviate or even avoid such a situation, employees are eager to obtain alternative resources from HPWS, because these systems can be regarded as a pivotal resource to support and encourage them to engage in tasks.

Hypothesis 4. LMX moderates the positive relationship between HPWS and work engagement, such that it is stronger for low-quality LMX.

Combining the mediating effect of work engagement and the moderating role of LMX in the HPWS and proactive behavior relationship, we propose a moderated mediation hypothesis. That is, the positive and indirect effect of HPWS on proactive behavior via work engagement may be moderated by the quality of LMX. As explained before, subordinates with high-quality LMX are less likely to depend on HPWS, mitigating their effects on work engagement and, in turn, proactive behavior. In contrast, when LMX quality is low, HPWS is more effective in motivating employees to enhance their work engagement and proactivity. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5. LMX negatively moderates the mediated relationship between HPWS on proactive behavior through work engagement, such that the mediated relationship will be weaker under high-quality LMX than low-quality LMX.

Method

Sample and procedure

Our data were collected from white-collar workers at private companies located in China. Only companies with HR departments were solicited, as they are more likely to implement formal HR systems (e.g., HPWS) across functional departments. To reduce potential common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), we surveyed the participants from different sources in two time periods (1-month intervals). At Time 1, the supervisors were asked to rate HPWS, whereas the employees assessed LMX quality and work engagement. At Time 2 approximately four weeks later, the employees reported their proactive behavior in the workplace. Considering the complexity of the study design and maximizing the participation rate, the authors invited friends who are middle managers in different private companies as liaison persons. Each contact was responsible for randomly selecting 3–5 work groups in their company and assisting in the distribution and collection of survey packages.

The total matching questionnaires were initially distributed to 297 supervisory-employee dyads. We received a final sample size of 204 employees nested in 54 groups from 15 organizations, yielding a response rate of 69.69% for the subordinates and 85.71% for the supervisors, respectively. Of the subordinates, 54.9% were female, with an average age of 27.94 years; they, on average, had 2.87 years of working experience at the firm. Of their immediate supervisors, 57.4% were middle managers, with an average organizational tenure of 2.78 years. The participants came from various functional departments and diverse business sectors. With respect to the participants' job functions: 20.4% were from production, 25.9% from sales and marketing, 14.8% from accounting and finance, 24.1% from research and development and 14.8% from other functions.

Measures

In addition to the Chinese version of the work engagement scale provided by the author (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006), the remaining scale items were translated from English to Chinese via the back-translation process (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980). Unless otherwise indicated, all items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

High-performance work systems

Consistent with existing research (e.g., Lee et al., Reference Lee, Pak, Kim and Li2019; Zhang, Bal, Akhtar, Long, Zhang, & Ma, Reference Zhang, Bal, Akhtar, Long, Zhang and Ma2019), we invite group supervisors to evaluate the HPWS. The instruction to them was to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement based on the actual HR practices implemented in your group.

HPWS were measured using an 18-item scale developed by Jiang (Reference Jiang2013) based on the Chinese context. Following previous studies (e.g., Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, Kalleberg, & Bailey, Reference Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, Kalleberg and Bailey2000; Jerez-Gómez, Céspedes-Lorente, & Pérez-Valls, Reference Jerez-Gómez, Céspedes-Lorente and Pérez-Valls2019; Lepak et al., Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006) we use the ability-motivation-opportunity framework to categorize these items/practices into three dimensions: skill-enhancing HR practices (six items, e.g., ‘Recruitment process uses many different recruiting sources (agencies, universities, etc.)’), motivation-enhancing HR practices (six items, e.g., ‘Performance appraisals are based on objective, quantifiable results’), and opportunity-enhancing HR practices (six items, e.g., ‘If a decision made might affect employees, the company asks them for opinions in advance’). Cronbach's α was .756, .823, and .804, respectively.

To reflect our concern for the overall HRM system and consist with the prior literature (e.g., Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2021; Gürlek & Uygur, Reference Gürlek and Uygur2021; Jeong & Choi, Reference Jeong and Choi2016; Jerez-Gómez, Céspedes-Lorente, & Pérez-Valls, Reference Jerez-Gómez, Céspedes-Lorente and Pérez-Valls2019; Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, Reference Liao, Toya, Lepak and Hong2009; Sun, Aryee, & Law, Reference Sun, Aryee and Law2007), we then use the dimensions to create a unitary index for HPWS to investigate the effect of a coherent system on employee outcomes. Moreover, high levels of internal reliability for the measure (Cronbach's α = .805) also provide support for our use of a unitary index (Jiang, Reference Jiang2013).

Work engagement

Work engagement was measured with a nine-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006), which has been widely used in the Chinese context (Lu, Xie, & Guo, Reference Lu, Xie and Guo2018; Zhou, Ma, & Dong, Reference Zhou, Ma and Dong2018) and has shown an excellent (cross-national) validity, reliability, and stability (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006; Seppälä et al., Reference Seppälä, Mauno, Feldt, Hakanen, Kinnunen, Tolvanen and Schaufeli2009). This scale consists of three subscales: vigor (e.g., ‘At my work, I feel bursting with energy’), dedication (e.g., ‘I am enthusiastic about my job’), and absorption (e.g., ‘I feel happy when I am working intensely’). Each dimension was assessed using three items. All items were scored on a 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Consistent with Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006), the three dimensions of engagement were aggregated to assess an overall work engagement. Cronbach's α was .913.

Proactive behavior

We used a seven-item scale developed by Frese, Fay, Hilburger, Leng, and Tag (Reference Frese, Fay, Hilburger, Leng and Tag1997) to measure proactive behavior. A sample item is ‘Whenever something goes wrong, I search for a solution immediately.’ Cronbach's α was .838.

Leader-member exchange

Scandura and Graen's (Reference Scandura and Graen1984) seven-item scale was used to assess LMX. Sampled item is ‘I have enough confidence in my immediate supervisor that I would defend and justify his or her decisions if he or she were not present to do so.’ Cronbach's α was .860.

Control variables

At the individual level, we control for employees' age, gender (male = 1, female = 0), education background, and organizational tenure, which have been shown to affect proactive behavior (e.g., Bindl & Parker, Reference Bindl, Parker and Zedeck2010; Bolino & Turnley, Reference Bolino and Turnley2005; Frese & Fay, Reference Frese and Fay2001; Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010; Thomas, Whitman, & Viswesvaran, Reference Thomas, Whitman and Viswesvaran2010). At the organizational level, as suggested by Huang, Wright, Chiu, and Wang (Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008), we control for the organizational tenure of supervisors as this demographic variable could influence the LMX quality. Tenures of both followers and leaders were measured in months.

Results

Measurement model

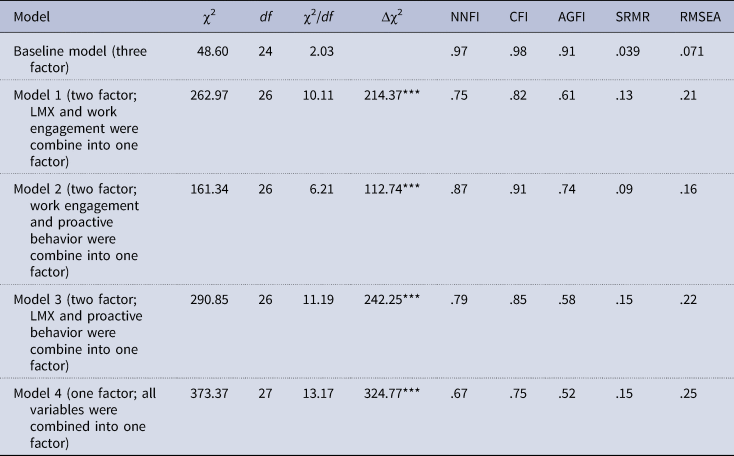

We first carried out a confirmatory factor analysis to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of the three focal level 1 latent variables (i.e., work engagement, LMX, and proactive behavior). The HPWS measured by leaders were not included in these analyses because they were only available at the group level. We use item parceling to estimate the latent constructs, since the model would exceed the recommended parameters to sample size ratio for estimation (1:5; Bentler & Chou, Reference Bentler and Chou1987) if all the measurement items were included as observed indicators (Landis, Beal, & Tesluk, Reference Landis, Beal and Tesluk2000; Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002). Following Little et al. (Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002), we combine the items of work engagement into three parcels according to its sub-dimensions (vigor, dedication, and absorbtion) categorized in Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006). Furthermore, for LMX and proactive behavior, three indicators for each construct were created by randomly aggregating items (Landis, Beal, & Tesluk, Reference Landis, Beal and Tesluk2000; Little et al., Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002). As shown in Table 1, the hypothesized baseline (e.g., three-factor) model fits the data well (χ2(24) = 48.60; non-normed fit index (NNFI) = .97; comparative fit index (CFI) = .98; adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = .91; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .039; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .071). Standardized factor loadings ranged from .66 to .92 and were statistically significant (p < .001), and the average variance extracted values of all the variables were higher than .50, all of which confirmed the convergent validity (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2013). Furthermore, following Williams and Anderson (Reference Williams and Anderson1994), we collapsed some of the factors to form a range of alternative models. The results in Table 1 indicate that none of these models is superior to our baseline model. For example, a two-factor model by loading LMX and work engagement onto the same factor fits significantly worse (χ2(26) = 262.97; Δχ2 = 214.37; р < .001; NNFI = .75; CFI = .82; AGFI = .61; SRMR = .13; RMSEA = .21). Hence, the above results support the discriminant validity of our measures.

Table 1. Results of measurement model comparison

NNFI, non-normed fit index; CFI, comparative fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

*** p < .001.

Lastly, we used Harman's one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) to check for the possibility of common method bias. Results showed that single (common method) factor model fits were unsatisfactory (χ2(27) = 373.37; NNFI = .67; CFI = .75; AGFI = .52; SRMR = .15; RMSEA = .25) and significantly worse than the proposed three-factor model (Δχ2 = 324.77, р < .001), which indicated that the common method variance was not detected in our data.

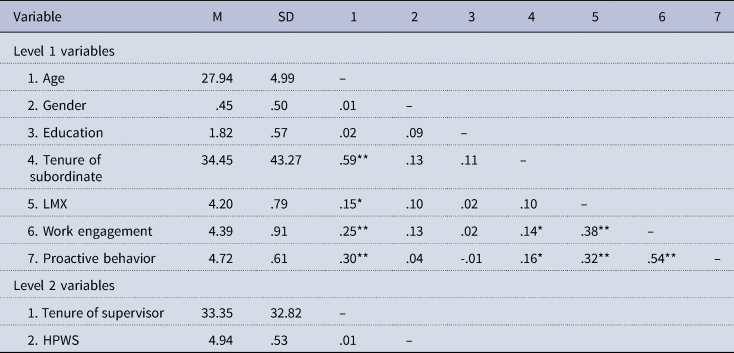

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviation, internal consistency reliabilities, and zero-order Pearson correlation of all variables. These results show that work engagement was significantly correlated with LMX and proactive behavior.

Table 2. Means, SDs, reliability coefficients, and correlations among the variables

LMX, leader-member exchange; HPWS, high-performance work systems.

Note: N = 204 at individual level and N = 54 at group level. SD, standard deviation; gender, 1 = man, 0 = woman; education, 1 = vocational college degree or below, 2 = bachelor degree, 3 = master degree, and 4 = doctoral degree.

*p < .05; **p < .01 (two tailed).

Test of hypotheses

As individual respondents were nested within groups (under the same supervisor within a group), we first conducted hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to test Hypotheses 1 through 4. Based on Maas and Hox's (Reference Maas and Hox2005) rule of thumb for power in multilevel modeling (i.e., a minimum of 30 cases at higher level), it seems that the present study's sample size at group level (54 group) is adequate for robust estimations. Second, we used the Monte Carlo resampling method to test Hypothesis 5 (moderated mediation model).

Prior to testing the hypotheses, we verified that there was enough between-group variance in work engagement and proactive behavior, as indicated by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC[1]). The ICC(1) values for work engagement and proactive behavior were .21 and .17, respectively, indicating a significant between-department variance in both and suggesting that the HLM is an appropriate analytical technique.

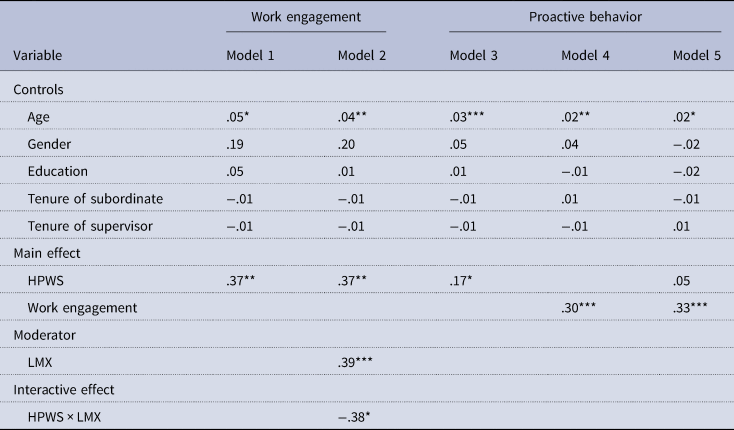

Table 3 presents the results of the HLM. Hypothesis 1 stated that HPWS were positively associated with work engagement. As reported in Model 1, we found that HPWS had a positive and significant relationship with work engagement (γ = .37, р < .01) after controlling for employee age, gender, education, and organizational tenure as Level 1 predictors and organizational tenure of leaders as a Level 2 predictor in the analyses. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 3. Results of hierarchical linear modeling analysis

HPWS, high-performance work systems; LMX, leader-member exchange.

Notes: N = 204 individuals and 54 functional groups. Entries corresponding to the predicting variables are estimations of the fixed effects (γ values) with robust standard errors.

*p < .05;.**p < .01; ***p < .001.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that work engagement would be positively related to employees' proactive behavior. The result in Model 4 showed that work engagement was significantly and positively associated with proactive behavior (γ = .30, р < .001), thus, supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that work engagement mediates the relationship between HPWS and proactive behavior. According to Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986), we followed a three-step procedure to establish a mediation hypothesis.

The results in Model 3 revealed that HPWS had a significant effect on proactive behavior (γ = .17, p < .05), thereby, lending support for the first step. The second step was met in our testing of Hypothesis 1, which established that HPWS were positively related to employees' work engagement (Model 1). In testing Step 3, we included HPWS, work engagement, and proactive behavior in the HLM analyses. The results present in Model 5 indicated that work engagement was significantly associated with proactive behavior (γ = .33, р < .001); HPWS no longer significantly predicted proactive behavior (γ = .05, n.s.), which revealed that work engagement fully mediated the relationship between HPWS and proactive behavior. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported. In addition, we used the parametric bootstrap method to further confirm the significance of the mediation effect. With 20000 Monte Carlo resamples, the results showed that the indirect relationship between HPWS and proactive behavior via work engagement was significant (indirect effect = .16, 95% CI = [.09, .25]), which further supports Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 represented the cross-level moderating effect of LMX (a Level 1 variable) on the relationship between HPWS (a Level 2 variable) and work engagement (a Level 1 variable). Based on the HLM analysis results reported in Model 2, the interaction between HPWS and LMX was significantly related to work engagement (γ = −.38, р < .05), Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

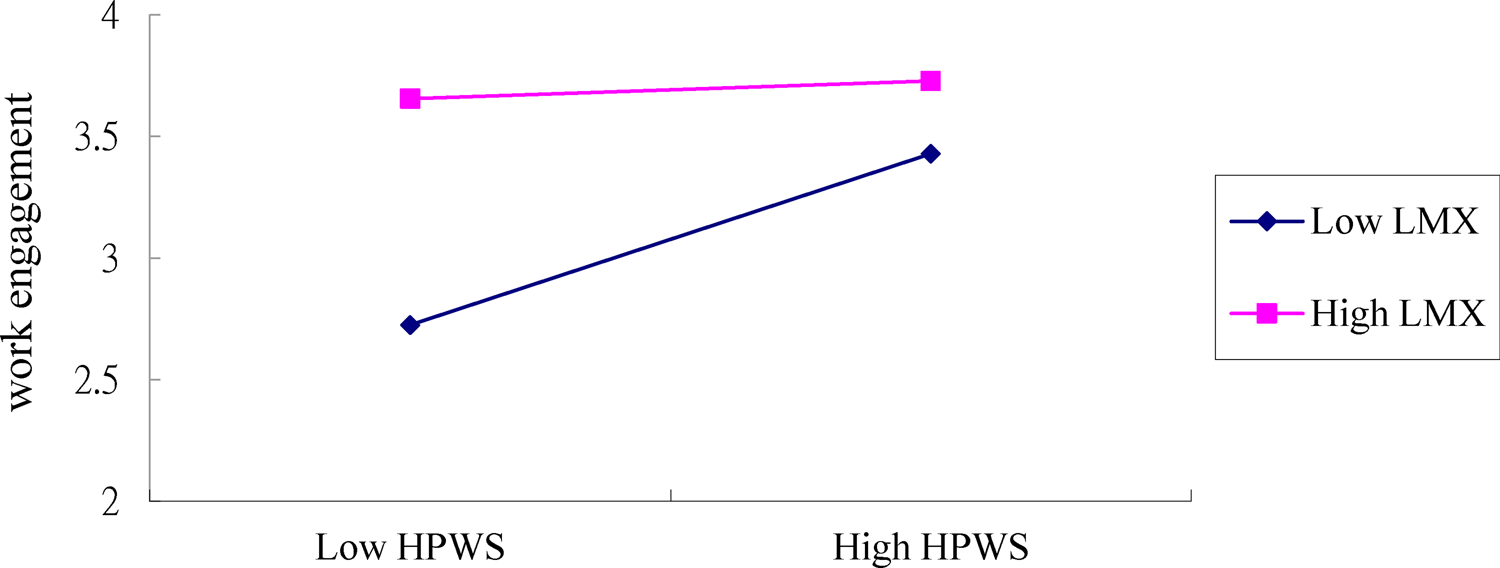

To further illustrate the nature of the interaction effects between HPWS and LMX, we conducted simple slope analyses and plotted graphs using values of one standard deviation below the mean and one standard deviation above the mean of LMX (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). The plot in Figure 2 indicates that the relationship between HPWS and work engagement was positive and significant when LMX was low (simple slope = .66, p < .001). However, the relationship was nonsignificant when LMX was high (simple slope = .07, n.s.), which provided further support for Hypothesis 4.

Figure 2. The moderating role of LMX in the relationship between HPWS and work engagement.

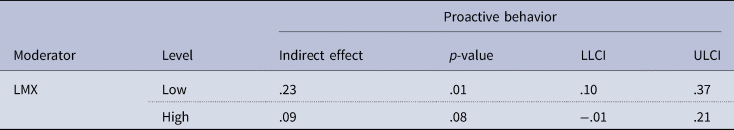

To examine the moderated mediation hypotheses (Hypothesis 5), we used the Monte Carlo resampling method to compute 95% confidence intervals (CIs; Preacher & Selig, Reference Preacher and Selig2012). Based on 20,000 resamples (see Table 4), the results indicated that the indirect effect of HPWS on proactive behavior through work engagement was positive and significant when LMX was low (indirect effect = .23, 95% CI [.10, .37]), but this indirect effect was not significant when LMX was high (indirect effect = .09, 95% CI [−.01, .21]). Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Table 4. Moderated mediation results for proactive behavior across levels of LMX quality

LMX, leader-member exchange; LLCI, lower limit of 95% confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit of 95% confidence interval.

Note. N = 204 at the individual level, N = 54 at the group level. Bootstrap sample size = 20,000. Indirect effects were based on unstandardized regression coefficients.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a multilevel framework to shed light on the underlying mechanism between high-level HPWS and employees' proactive behavior. Integrating the JD-R model and COR theory, we examined an integrative model of how work engagement mediates the effect of HPWS on proactivity and the moderating role of LMX in this process. The results of this study indicate that work engagement fully mediates the HPWS-employee proactivity relationship. Furthermore, we also found support for our moderated mediation model, which indicated that high-quality LMX attenuated the positive effect of HPWS on proactive behavior via work engagement. These findings have several theoretical and practical implications, which we discuss below.

Theoretical implications

This study provides three main theoretical contributions to the existing literature. First, previous studies have predominantly concentrated on how single motivational states, such as role breadth self-efficacy (Beltrán-Martín et al., Reference Beltrán-Martín, Bou-Llusar, Roca-Puig and Escrig-Tena2017) and intrinsic motivation (Andreeva & Sergeeva, Reference Andreeva and Sergeeva2016) can bridge the gap between HR systems and proactive behavior. Our research comprehensively extends prior knowledge by testing the mediating role of work engagement and demonstrates that employees who are energetic and enthusiastic about their work are more likely to transform HPWS into proactivity through multiple motivational processes (i.e., ‘reason to’ and ‘energized to’). Our findings not only provide empirical evidence for the theoretical framework developed by Parker, Bindl, and Strauss (Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010), but also respond to the call for bringing more motivational states to link HPWS with proactive behavior (Beltrán-Martín et al., Reference Beltrán-Martín, Bou-Llusar, Roca-Puig and Escrig-Tena2017). In addition, while the connection between work engagement and proactive behavior is often explained from the perspective of the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Eldor & Harpaz, Reference Eldor and Harpaz2016; Maden, Reference Maden2015), these literatures ignore the fact that being proactive also bear unpredictable challenges or threats (Frese & Fay, Reference Frese and Fay2001; Wu & Parker, Reference Wu and Parker2017). Therefore, drawing on COR theory, we add new insights to this field by noting that a highly engaged workforce with abundant resources is more dauntless of potential losses and thus have higher propensity to perform risk-taking actions. More importantly, by integrating the JD-R model with COR theory, this study also provides a solid theoretical foundation to describe how and why HPWS, as a key motivator, can boost employees' work engagement and in turn stimulate them to behave more proactively.

Second, by identifying LMX as a moderator in the above-mentioned process, we found that the impact of HPWS was contingent upon the relationship quality between supervisors and their immediate subordinates. To date, although the role of first-line managers in HRM has been discussed, this stream of literature primarily has focused on how leadership behaviors (i.e., empowering leadership, ethical leadership; Chuang, Jackson, & Jiang, Reference Chuang, Jackson and Jiang2016; McClean & Collins, Reference McClean and Collins2019; Neves, Almeida, & Velez, Reference Neves, Almeida and Velez2018) moderate the relationship between HRM and performance outcomes. The present study extends extant research by showing that the dyadic LMX relationship also acts as a critical contingency between HPWS and proactive behavior via work engagement. Even though Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2019) attempted to put LMX back into HRM research, unfortunately, he only managed to identify the joint impact of LMX and individual practice (i.e., perceived opportunities for development) instead of HRM systems. As Lepak et al. (Reference Lepak, Liao, Chung and Harden2006: 218) state that ‘failure to consider all of the HR practices that are in use neglects potential important explanatory value of unmeasured HR practices’; hence, this study provides a more advanced understanding about the role of LMX in the bundle of HR practices and, importantly, responds to recent calls for exploring the potential interactive effects between SHRM and leadership (Steffensen et al., Reference Steffensen, Ellen, Wang and Ferris2019).

Finally, thus far, most of our limited exploration of the interplay between LMX and HRM is rooted in the social exchange theory (Blau, Reference Blau1964), which notes that these two concepts produce mutually reinforcing, synergistic benefits (e.g., Audenaert, Vanderstraeten, & Buyens, Reference Audenaert, Vanderstraeten and Buyens2017; Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2019). Our study provides a different perspective and contributes to advancing this theoretical debate by using COR theory and proposing that HPWS and LMX are two different types of resources in the workplace that can substitute for each other. The results of the present study imply that HPWS is extremely crucial for work engagement and proactive behavior when LMX is low, but may not be as important when employees have established high-quality LMX relationships with their direct supervisors. Furthermore, our results further enrich the substitutive hypothesis in the COR theory: past studies have mainly shown substitution effects between personal resources and other levels of resources, such as social resources (Boon & Kalshoven, Reference Boon and Kalshoven2014; Shantz, Alfes, & Latham, Reference Shantz, Alfes and Latham2016). Our finding confirms that such substitutive relationships could also exist between leadership resources (i.e., LMX) and organizational resources (i.e., HPWS).

Practical implications

Our results also offer several important implications for management practices. One practical implication is about establishing HPWS in the organization. Our study demonstrates that HPWS is effective in improving employees' work engagement and proactive behavior. Hence, organizations should devote adequate resources to design comprehensive HPWS practices, such as rigorous selection, competitive compensation, etc. Besides, senior managers need to value the well-being and welfare of their employees and continually and publicly stress the importance of HR practices, so that department or group managers can genuinely value and execute these arrangements (Arthur, Herdman, & Yang, Reference Arthur, Herdman and Yang2016; Steffensen et al., Reference Steffensen, Ellen, Wang and Ferris2019).

Another practical implication is related to the moderating role of LMX quality. Our research indicates that there is a substitution effect between HPWS and LMX, which implies that organizations should evaluate their own organizational status and take different actions accordingly. More specifically, when structured HPWS were adopted, line managers could pay more attention to understanding the external market and tap the potential needs of customers, rather than consuming time or energies on developing a good dyadic relationship with each employee. Contrarily, when the organization does not have a well-established HR system, more programs need to be offered to assist line managers to build and maintain high-quality relationships with their subordinates. Possible arrangements may include: the HR department can provide more developmental training for managers on transformational leadership and interpersonal skills (Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, & Ferris, Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012; Loi, Ngo, Zhang, & Lau, Reference Loi, Ngo, Zhang and Lau2011; Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang, & Chen, Reference Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang and Chen2005). In addition, department managers should actively participate in the interview process, selecting potential candidates with characteristics such as conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and positive affectivity (Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012). Finally, additional supportive/appreciation sessions can be conducted to allow supervisors and subordinates to exchange their thoughts and feelings and understand each other's role expectations, thereby enhancing mutual understanding, reducing role conflict, and facilitating positive interactions between them (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008).

Limitations and future research directions

Like any other study, the current research is not exempt from several limitations. First, given that our data were collected from two different sources (subordinates and their immediate supervisors) in two time periods (1-month intervals), the common method bias variance could not be a major concern (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Indeed, the results of a single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) and the statistically significant interactions (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010) also illustrated that common method bias was less of a threat to our research.

Second, we only chose private companies as the study target to test our theoretical model, which may restrict the generalizability of our results. Future research could test our model in other contexts (e.g., state-owned and foreign-owned enterprises). Besides, this analysis used data collected from China, which also raises some concerns regarding the generalizability of our findings to other cultures. Compared with Western countries (e.g., the United States), Chinese societies have high power distance and greater emphasis on collectivism (Lee, Bobko, & Chen, Reference Lee, Bobko and Chen2006), and employees in the former societies respond more positively to the quality of LMX (Lee, Scandura, & Sharif, Reference Lee, Scandura and Sharif2014; Selvarajan, Singh, & Solansky, Reference Selvarajan, Singh and Solansky2018). Indeed, Lee, Scandura, and Sharif (Reference Lee, Scandura and Sharif2014) evidenced that culture (power distance and individualism/collectivism) moderates the relationship between LMX and affective commitment, and such positive relationship is stronger for subordinates in the individualistic-low power distance country (i.e., the United States) than for those in the collectivistic-high power distance country (i.e., Korea). Based on this, we reasonably conjecture that our proposed model will be also supported in the Western context and the results may even be more significant. Future research could examine our research model in a Western setting and conduct a cross-cultural study to validate and expand our conclusions.

Third, considering that some of our groups and individual samples come from the same companies, there is no doubt that certain company-level constructs, especially intended HR policies designed by organization (i.e., organizational-level HPWS), will influence HR practices actually implemented in the functional group (i.e., group-level HPWS) (Purcell & Hutchinson, Reference Purcell and Hutchinson2007; Wright & Nishii, Reference Wright and Nishii2007). In order to comprehensively understand the HRM-performance causal chain (Purcell & Hutchinson, Reference Purcell and Hutchinson2007; Wright & Nishii, Reference Wright and Nishii2007), we encourage future scholars to add organizational-level HPWS on top of our existing framework, and even further identify what factors might account for the differences between organizational-level HPWS and group-level HPWS.

Lastly, in contrast to Western societies that focus on formal work relationships, in their Eastern counterparts, especially in China, people value strong private interpersonal ties (i.e., guanxi) (Aryee & Chen, Reference Aryee and Chen2006). Thus, Chinese leaders and their followers would blur business and personal relationships; then, they would establish an informal exchange relationship, namely supervisor-subordinate guanxi (SSG) (Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang, & Lu, Reference Chen, Friedman, Yu, Fang and Lu2009). Accordingly, we suggest there is a need for future studies to explore and extend our findings to examine whether the SSG has similar moderating effects in the Chinese cultural setting.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our greatest thanks to three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and valuable suggestions. This study is funded by the Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (the approval number: 18YJC630089), the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (the approval number: 2018JJ2407; 2020JJ4592), and the Science-Technology Plan for Excellent Young and Middle-aged Innovative Team of Hubei Universities (the approval number: T2021040).

Conflict of interest

None.

Chiou-Shiu Lin (PhD, National Sun Yat-sen University) is an associate professor of management at the Business School, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, China. He has published articles in Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research among others. His research programs include group affect, organizational identification, and leadership.

Ran Xiao is a PhD student at the School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China. Her research interests include strategic human resource management and leadership.

Pei-Chi Huang (PhD, National Sun Yat-sen University) is an assistant professor of management at the Institute of Business and Management, National University of Kaohsiung, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. She has published articles in Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research among others. Her research interests include transformational leadership, organizational identification, and family business management.

Liang-Chih Huang (PhD, Iowa State University) is a professor of management at the Department of Labor Relations, National Chung Cheng University, Chia-Yi County, Taiwan. He has published articles in Journal of Business Ethics, Personal Review among others. His research programs include human resource management and organizational behavior.

Ming Jin is a PhD student at the Economics and Management School of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China. Her research interests include strategic human resource management and ethical leadership.