Introduction

Competition law and enforcement are experiencing something of an awakening in the last decade. Having remained relatively muted since neoliberal economics took hold, and with a reduced role for competition law to correct the occasional malfeasance in the market, a series of high-profile cases, growing dissatisfaction with economic power (particularly in high technology markets), and mounting pressure to recognise competition law's diverse faces and role, have re-launched competition law to the forefront of governments’ tools to restore trust in the markets.Footnote 1

Central to the renewed interest in the role of competition law was the question of what objective it was designed to achieve. It is impossible to decide whether competition law is the appropriate tool with which to correct the various perceived faults and imperfections of markets if it is not first known what this tool is meant to accomplish. The European Commission's steady stream of influential investigations and regulatory measuresFootnote 2 centred this debate in the European Union (EU) and turned the world's attention to it for answers and leadership by example, including guidance on what competition law sets out to achieve.Footnote 3

Over the years, numerous textual, historical, and teleological interpretations of competition law have attributed diverse and even contradictory objectives to it, ranging from consumer welfare, to total welfare, efficiency, the protection of the competitive process, the advancement of EU integration and others.Footnote 4 Shifting the focus from one of those goals to another can impact not only the outcome of enforcement activity, but, crucially, whether the enforcement mechanism is engaged at all. At the same time, the discourse on the goals of competition law expanded also in the direction of what competition law should not aim to achieve, notably, the protection of (inefficient) competitors, as academic commentary noticed that strands of case law could be interpreted as advancing this misaligned goal.Footnote 5

The recent meteoric rise of star technology firms (known by the acronym GAFAM for Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft, which in 2020 surpassed a combined market capitalisation of $5 trillion – larger than the 4th largest state economy in the world) added or reinvigorated various aspects to the debate on the role of competition law. The control of undue corporate market power remained an uncontested goal of competition law but concerns around stark wealth inequalities and exploitation of workers often linked to the monumental success of star firms raised the question of whether competition law should also pursue broader socio-economic interests such as wealth redistribution, labour protection, and fairness.Footnote 6 This was particularly pronounced in what came to be known as the neo-Brandeisian antitrust wave, which sees an expanded role for antitrust law, free from the shackles of the welfare-maximalist and efficiency-oriented Chicago School.Footnote 7 Some have gone as far as to suggest that competition law, having been entrusted with the duty to rein ‘bigness’, is also relevant when bigness is used to corrupt the democratic process or undermine consumer privacy.Footnote 8

In short, as markets have been undergoing extreme changes over the past decades, competition law has been called time and again to respond to a host of market problems that have been encountered along the way. But before it can be engaged, it must first be established that competition law is the right tool for the job; in other words, whether the call for help falls within the goals and purposes of what competition law has been tasked to achieve. As memorialised by Robert Bork in his now classic adage, ‘antitrust policy cannot be made rational until we are able to give a firm answer to one question: What is the point of the law – what are its goals? Everything else follows from the answer we give’.Footnote 9

On this fundamental inquiry, work has been plentiful. A strand of research has attempted to pinpoint the goals of competition law as they emerge through the legislative intent of lawmakers at the time of the laws’ passing.Footnote 10 Competition laws are among the most concise, cryptic, and abstract legal provisions, and so attempts to uncover the hidden details by looking at what the lawmakers might have meant seems reasonable. But the main, and potentially fatal, shortcoming of relying on legislative intent is that ‘rule decision-making is chaotic’,Footnote 11 there is no such thing as a uniform and cohesive legislative intent, rendering the concept ultimately ‘a fiction’.Footnote 12 In EU competition law, this general obscurity of legislative intent is further exacerbated by the fact that the main provisions are but two articles in what are otherwise quite generally-drafted ‘programmatic’ treaties with rather broad, interconnected, goals and a plethora of policy areas, making gauging the legislative intention specifically for competition rules a difficult task. Additionally, relying on legislative intent for Treaty text negotiated in the 1950s would strip EU competition law of its EU law nature, which includes common law style evolution through case law generated jurisprudence.Footnote 13 Moreover, even assuming that consensus could emerge around a certain legislative intent behind competition laws, this does not preclude an indefinite number of secondary-order goals that may derive from the primary goal. For instance, assuming welfare is the primary goal, would dynamic efficiency be part of it or would it be a separate goal that was not intended ab initio? If we allow welfare to be bifurcated into secondary-order goals, how do we discover them and where do we draw the line?

Partly as a response to these concerns, another strand of scholarship rejects the idea that competition laws are purposed through a historical interpretation assigning a single goal (whatever that might be), and instead see them as a catch-all tool for the supervision of markets that expresses multifarious social, political, and economic considerations.Footnote 14 This normative approach regards competition laws as the last line of defence against practices that harm consumers, businesses, or the very fabric of economic life when sectoral regulation is missing, and they can therefore be tasked with an open-ended list of goals and purposes.Footnote 15

Both of these strands draw support from the case law, and additional lines of research also use case law to derive the goals of competition law as they emerge through the judicial interpretation of the relevant provisions.Footnote 16 This is only natural, since the final word rests with enforcers and courts, and so their decisions are a key source of how the law is to be perceived not only statically but in a historical depth too, including legislative intent. In the words of the Court of Justice ‘the interpretation of a provision of EU law requires that account be taken not only of its wording and the objectives it pursues, but also of its context and the provisions of EU law as a whole. The origins of a provision of EU law may also provide information relevant to its interpretation’.Footnote 17 However, so far, there has been no attempt to analyse the entirety of EU institutions’ jurisprudence for insights that can only emerge through an aggregate view of decisional practice.

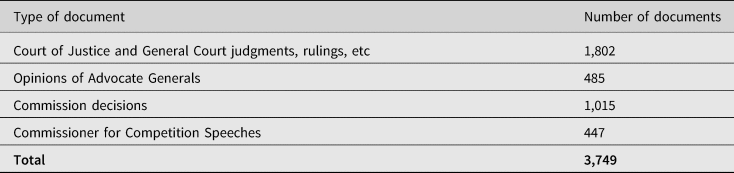

We aim to fill this gap by compiling a high-level picture of the entire decisional practice of EU institutions on competition law by examining almost 4,000 sources: 1,802 Court of Justice and General Court decisions, 485 Advocate General opinions, 1,015 European Commission decisions, and 447 Commissioner for Competition speeches, from 1962 to 2020, covering all three major areas of competition law, namely anticompetitive agreements (Article 101 TFEU), unilateral conduct and abuse of dominance (Article 102 TFEU) and concentrations. From this, we aim to distil seven broad goals of competition law – efficiency, welfare, economic freedom and protection of competitors, competition structure, fairness, single market integration, and competition process – and to subsequently extract qualitative and quantitative insights.

Our research complements existing work in that it moves the focus away from a small number of highly authoritative sources – whether historical documents like travaux preparatoires, or landmark cases – and instead develops insights that can derive only from a comprehensive overview of all available EU institution sources. The quantitative and qualitative analysis we perform does not discount the authoritativeness of key sources nor of the accompanying scholarly analysis; in fact, we observe that a small number of decisions and opinions have shaped decisional practice by serving as constant points of reference. Yet these decisions and opinions do not represent the totality of EU institutions’ insights, and while less notable decisions and opinions, taken individually, would probably not change our perception of competition law's goals and purposes, the combined insights from the entire volume of EU institutions’ output might (as it is the case, for example, with our results on debunking the influence of fairness in competition law practice (see section 3(d) below)). Our study also allows us to observe differences across institutions, track the evolution of EU institutions’ thinking through time, and identify trends and patterns, which would remain hidden without quantitative analysis. In doing so, the study helps scholars and authorities gain a fuller understanding of competition law and its raison d’être in the EU system. Lastly, we also make our datasets available for other researchers and enforcers to use in the hope of engendering more research into and better understanding of EU competition law.Footnote 18

A number of insights emerge from our analysis. Some corroborate what past theoretical work suspected or argued for – the value in this case lies in bringing conclusive empirical backing to the debate. Other insights resolve more controversial issues, therefore advancing our understanding of the true state of affairs. In detail, we provide exhaustive evidence that EU competition law pursues a multitude of goals concurrently, which dispels the myth of monothematic competition law. This has also historically been the case, even if the different goals fluctuate in prevalence over time as we document on a year-by-year basis. Surprisingly, we do not find evidence that scholarly work or prior case law consistently affect the perceived goals of competition law, which suggests that the goals are inherent. Further, while competition law pursues a multitude of goals, it prioritises the process of competition rather than directly the achievement of a desirable outcome (eg efficiency, welfare maximisation, etc). We also show that fairness, despite media popularity, does not fare highly in the decisional practice of any EU institution. It only features prominently in the speeches of Commissioner Vestager. Relatedly, we observe that different Commissioners seem to emphasise different goals during their terms, with Kroes promoting welfare and Vestager promoting fairness. We also observe that the Commission places emphasis on different goals than do the Court and the Advocate Generals, and Commissioner speeches reflect yet different emphasis too. The Commission assigns more value to welfare and to the protection of competitors and commercial freedom, but less value to efficiency than the Court and the Advocate Generals. Speeches emphasise welfare and fairness more than EU institutions in their decisions. Another conclusion we reach is that, somewhat unexpectedly, ordoliberal objectives still linger and may recently be on the rise again. Lastly, the rate of cases referencing competition law goals over the years has remained steady to slightly increased, with the Commission leading the increase, perhaps in response to the ‘more economic approach’ instituted in the early 2000s.

1. Literature review and the state of scholarship on the goals of competition law

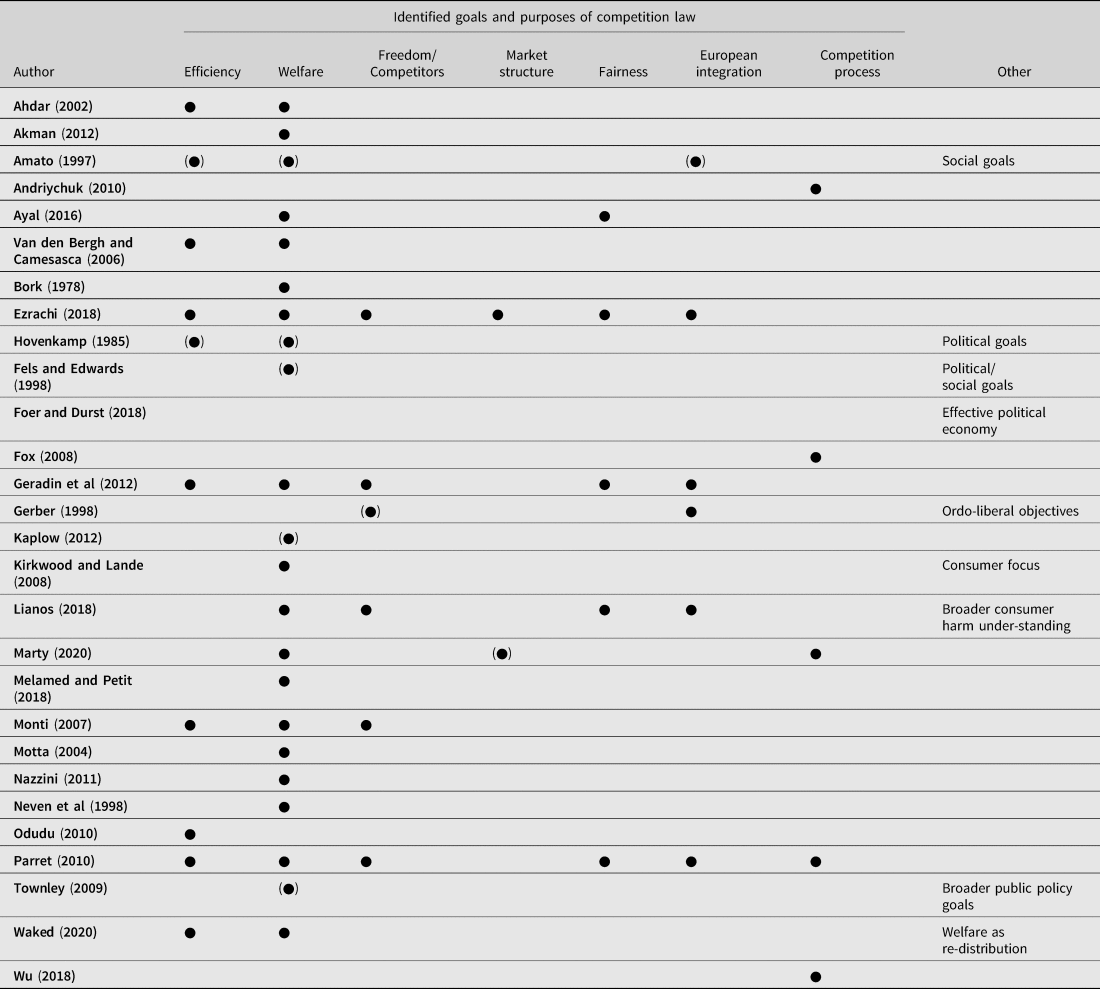

Competition laws have existed for over 130 years.Footnote 19 Competition law has been part of the EU's primary laws since the Treaty of Rome in 1957; inspired by it (and by the US antitrust rules), competition laws now exist in more than 110 countries and territories around the world. Because competition laws are, in principle, notoriously brief and cryptic, deciphering their purpose and scope has been a popular exercise. The body of literature that has emerged over the yearsFootnote 20 offers both normative and positive law insights (for a summary see Table 1).

Table 1. Literature review of the goals and purposes of EU competition law

Our inquiry differs from the normative literature in that ours documents the goals and scope of competition law as a matter of institutional practice (as it manifests itself through the decisions of the Court and the Commission, the opinions of Advocate Generals, and the speeches of Commissioners for Competition) and it differs from the positive law literature in that our analysis is fully empirical whereas the empirical support in extant literature is only anecdotal. That said, the rich literature that pre-dates our work was instrumental in helping us identify the key goals of competition law to test and to make a first selection of corresponding keywords, which we expanded on as we went along with the search (see section 2 below).

In this section, we summarise prior literature. We do not evaluate the merit of the goals identified by the authors nor do we assess the soundness of their normative arguments. We only document their chosen goals and group them in seven broad families of goals that then feed into our methodology. As will be evident, there is stark disagreement on the perceived goals. Even within each of the seven broad goals, authors may still construe them differently. Moreover, many authors do not see one goal as being predominant, but instead argue for a variety of goals that competition law pursues concurrently.

The first broad goal is efficiency. Odudu is the author that best represents this goal as he rejects efforts to justify a competition policy concerned with more than efficiency, partly on the basis of an argument that policy-linking obligations contained in the TFEU, such as Article 168(1), may lack direct effect.Footnote 21 He considers that modern EU competition law has endorsed the Chicago School approach, both when it comes to methods of analysis (micro-economics, wherein high prices or low output are identified with inefficiency) and when it comes to goals. Regarding the latter, Odudu agrees with the Chicago approach (with reference to Bork's work) that the goal of competition policy is consumer welfare, understood, though, as a synonym for efficiency.

Amato shares this understanding of consumer welfare as synonym for efficiency.Footnote 22 Amato offers a historical overview of EU competition law's goals, focusing on the influence of the ordoliberals. He argues that competition law presents a dilemma for liberal democracies, as it strives to strike a balance between economic freedom on the one hand and constraining market power on the other hand. He identifies multiple purposes of EU competition law, including industrial policy, regional policy and social policy. He rejects the proposition that economic efficiency can be understood as a one-dimensional value concerned only with restrictions of output. At the same time, Amato advocates for separating EU competition law from industrial policy and thus freeing it of political and other considerations. This argument can be construed as an argument in favour of a welfare standard connected to economic efficiency.

Ahdar accepts efficiency as a goal, but rejects an efficiency-only model for competition law, as it fails to avoid subjectivity and value judgments by excluding distributional questions from decision-making. He puts forward the argument that competition law should not only promote efficiency, growth, and innovation, but also the long-term interests of consumers.Footnote 23

The second goal is welfare, which we interpret, based on the literature review, as encompassing both total welfare and consumer welfare as well as the protection of consumer interests (but not in the sense of consumer protection law as a separate field of law). This goal is well-represented in the literature, and in fact it manifests itself in different ways. Bork, in his seminal work, The Antitrust Paradox, argued that settling the issue of competition law's goals is necessary in order to rationalise competition policy.Footnote 24 He put forward consumer welfare as the proper goal for competition law, but advocated at the same time for an understanding of consumer welfare which excluded allocative considerations and redistribution.Footnote 25 In essence, Bork's thesis has been interpreted as arguing for total welfare, even though he refers to it as consumer welfare.Footnote 26 Contrary to Bork, Kirkwood and Lande look into the legislative history of US antitrust laws and determine that the ultimate goal of antitrust law is not to maximise the total wealth of society, but to protect consumers from behaviour that deprives them of the benefits of competition.Footnote 27 They further analyse case law to conclude that courts always side with protecting consumers over efficiency.

Within the European context, the debate on welfare has focused on the issue of redistribution and whether a total welfare goal is appropriate or a consumer welfare one. Many authors also identify EU competition law's orientation towards consumer welfare as connected with the broader interests of consumers and consumer protection. Neven et al are of the view that EU competition law is about consumer protection and the achievement of the best possible conditions for EU consumers.Footnote 28 According to them, in EU competition law ‘the choice has clearly been made to favour income redistribution from producers with market power to consumers’.Footnote 29 In their view, the ideological underpinnings of the project of European integration have favoured a policy choice to encourage redistribution to consumers and this has inevitably also flavoured EU competition law. They consider that this accords with a shift in economics towards a refocused economic analysis of law that examines law's distributive consequences. At the same time, they note that EU competition law's objectives may be contradictory and even inconsistent with economic theory.

Fels and Edwards argue that the legitimacy, desirability, and acceptance of EU competition law may hinge upon broader objectives with a clear political and social dimension.Footnote 30 That would necessitate consumer welfare to be interpreted in a way that takes into account broader objectives and that is sensitive to the redistributive effects of competition policy.

Motta argues that the proper goal of competition law should be total welfare.Footnote 31 According to Motta, in most situations choosing between a total welfare and consumer welfare standard would not make a difference in the work of a competition authority and the policy implications of the two standards are the same. However, he considers total welfare to be superior to consumer welfare, as he thinks the latter misses the point that consumers may also own companies through pension or investment funds, and would lead to companies having to price at marginal cost and disincentivise innovation. Townley disagrees, and rejects a total welfare goal for EU competition law. Instead, he argues that consumer welfare is the proper goal, but that in certain situations competition law should try to promote broader public policy goals.Footnote 32

Nazzini attempts an interpretation of Article 102 TFEU, based on various methods of interpretation common in EU law such as textual, teleological, systematic etc, in order to find its objective.Footnote 33 He argues that the goal of Article 102 TFEU is the maximisation of total social welfare through productivity growth. Accordingly, he rejects the relevance of fairness and ordoliberal goals. Akman, similarly to Nazzini, argues for a welfarist goal for Article 102 TFEU too and rejects the argument that fairness has a role to play as an independent policy goal in the concept of ‘abuse’ of a dominant position.Footnote 34 Instead, Akman adopts an understanding to references in Article 102 TFEU to ‘fairness’ that equates that term with ‘anticompetitive’.

Kaplow, too, accepts welfare as the proper goal of competition law and explains that competition law is not the best tool to achieve wealth redistribution.Footnote 35 As focusing on consumer welfare maximisation would mean trying to achieve such redistribution, he suggests that competition law rules are in fact more in accord with total welfare maximisation.

Melamed and Petit, responding to authors that have argued for an abandonment of consumer welfare, argue that the consumer welfare standard should be maintained in EU competition law, despite the perceived challenges with the enforcement of the rules vis-à-vis digital platforms.Footnote 36 According to the authors, the current discourse regarding digital platforms is attributable to misunderstanding the consumer welfare standard and any alternatives to that goal would not improve antitrust law.

Lianos accepts welfare as one of the goals of EU competition law, but sees that goal as being about the redistribution of wealth.Footnote 37 Along similar lines, Waked acknowledges the welfare goal of antitrust law but argues that it needs to be complemented by goals that are more oriented towards the public interest, and in particular equity and redistribution.Footnote 38 She claims that the welfare-related goal of maximising efficiency is one that serves the generation of wealth and that antitrust law should allow this to take place, but also have provisions in place to subsequently redistribute part of the generated wealth back towards consumers.

The third key goal is commercial or economic freedom and freedom to compete, a goal which relates to ensuring a level-playing field for competitors on a market. Monti is the author that has recognised this goal for EU competition law by connecting the core principles of post-World War II ordoliberalism to economic freedom.Footnote 39 He accepts, at the same time, that there is a clear trend from ordoliberalism towards consumer welfare and economic efficiency as goals of EU competition law.

Geradin et al argue that competition policy has to be responsive to changes, and responsiveness can be achieved by allowing its objective to fluctuate over time.Footnote 40 They identify four major objectives of EU competition law, including economic freedom and plurality, as well as consumer welfare, economic efficiency, and consumer choice and fairness. According to them, ‘undistorted competition’ is a multifaceted concept and all four objectives were in the minds of the founding fathers when drafting the Treaty of Rome. They also accept that EU competition law has additional goals, such as integration of the Member States’ markets.

The fourth goal we identified is market structure, in the sense of maintaining an effective competition structure and protecting competition as such. None of the reviewed authors argued that this was the only goal of competition law, but EzrachiFootnote 41 and MartyFootnote 42 include this goal as one among other goals.

The fifth overarching goal pursued by competition law is fairness. Notably, the literature advocating for fairness is relatively recent, a reflection of the fact that this goal has mostly been in the spotlight since Commissioner Vestager took office as EU Commissioner for Competition in 2014. The content of fairness varies amongst scholars. Ayal argues that both the strict welfare approach to competition law and the fairness approach are too narrow.Footnote 43 Instead, he argues that competition law should aim to protect a broader notion of fairness that takes into account the interests of all actors involved, including those of monopolists or undertakings with market power.

Ezrachi argues that the goals of EU competition law are not limited to consumer welfare, even if they ‘centre around, and are primarily consistent with, [it]’.Footnote 44 Instead, he argues that they are: (i) consumer well-being (which is broader than consumer welfare and includes, for instance, considerations of data protection and wealth distribution), (ii) effective competition structure, (iii) efficiencies and innovation, (iv) fairness, (v) economic freedom, plurality and democracy, and (vi) market integration. According to the author, this plurality of goals may embed normative values and flexibility, but reflects the EU's unique constitutional process and the societal context in which EU competition law operates.Footnote 45

Lianos argues that competition law is a hybrid type of law situated in between economic policy and social regulation.Footnote 46 He identifies a progression in the goals of EU competition law, from emphasis on market integration, to protecting smaller competitors, to protecting consumers. Lianos then contends that competition law ought to integrate considerations of inequality under a framework that seeks to avoid consumer harm, which he considers more appropriate as a goal than protecting consumer welfare. This broader conception of consumer welfare includes considerations of wealth transfers, and achieving an optimal level of consumer choice. These, according to Lianos, are linked to distributive justice and equality, the latter including notions of fairness.

Finally, as explained above with relation to welfare as a goal, many scholars see a connection between the consumer welfare standard and wealth redistribution from producers to consumers.Footnote 47 In that sense, there is a connection between those who see fairness as being connected to redistribution, though a distinguishing characteristic is that redistribution for fairness need not relate only to consumers but to citizens more broadly.

The sixth goal is European integration, or the realisation of the internal market. Several authors identify this as at least one of the goals for EU competition law. Gerber, for instance, argues that EU competition's goals can be understood correctly only in light of Europe's ordoliberalism tradition and the goal of achieving the common market.Footnote 48 Parret calls for more clarity and transparency regarding the goals of EU competition law. She considers that EU competition law has multiple goals, including market integration, but also economic freedom, economic efficiency, industrial policy, protection of small and medium-sized enterprises, justice, fairness, and non-discrimination, and protecting the interests of consumers.Footnote 49 Market integration is also one of the goals that Geradin et al ascribe to EU competition law.Footnote 50

The seventh and final key goal is protecting the competitive process. Fox suggests that antitrust law can be used to preserve the competitive process (or open-market perspective), thereby helping to preserve the incentives that produce productive, dynamic, and market efficiency.Footnote 51 She argues that since 1980, US courts have retreated from the tradition of protecting the competitive process (rivalry) and the openness of markets. Instead, they focus on a narrow understanding of efficiency, which is concerned mostly with lower market outputs. She argues that this is not related necessarily to efficiency but is instead the result of conservative (Chicago) economics. She contrasts this approach with EU competition law's approach to consumer welfare and efficiency, which is about process-and-access.

Andriychuk contests the utilitarian view of competition, including what he calls the Neo-Brussels school with its emphasis on consumer welfare.Footnote 52 The author adopts an ontological understanding of competition that blends elements of ordoliberalism and the Austrian school and argues that competition ought to be understood as a right in its own self that has – together with the political and cultural dimensions of competition – an important role to play in liberal democracies that should not depend on any efficiency outcomes. In essence, the author's argument can be understood as one about the goal of competition law being the maintenance of the competitive process.

Wu argues that the consumer welfare standard of competition law should be abandoned in favour of a standard that is about protecting competition.Footnote 53 According to Wu, the protection of competition standard is easier to apply because potential threats to the competitive process are far more obvious than reductions in consumer welfare. Wu concludes by suggesting a framework of analysis and provides examples of the considerations that ought to be used by an enforcer whose aim is the protection of the competitive process.

Marty reviews the historical evolution of EU competition law goals and notices the transition from ordoliberalism, which advanced a structural view of competition law, to the more economic approach, which adopted the US-imported welfare criterion as competition law's main objective.Footnote 54 He argues that welfare, in the form of total welfare rather than just consumer welfare, probably best captures the priorities of competition law, but that it needs to be complemented by a consideration for the protection of the process of competition as well. This is because digital markets may sometimes create harms that are not captured by the welfare criterion but can be explained on the grounds of harm to the process of competition.

Besides the seven key goals identified above, our literature review showed that scholars acknowledge a more complex function and constitution for competition law. Foer and Durst, for example, argue that the consumer welfare goal for antitrust is confusing and incomplete.Footnote 55 They consider that competition policy actually has multiple economic, political, cultural, and historic goals. They discuss specifically certain of these goals, namely making economics work for the electorate, stimulating growth, and making the most of limited resources by supporting various forms of efficiency. They argue that an approach that tries to promote all these goals through competition law has significant shortcomings. Instead, they propose that competition law's goal ought to be to promote and protect a political economy that provides a society's best mixture of competition and cooperation, given its culture, history, technology, and political situation at a given period of time. Hovenkamp argues that the Chicago School of antitrust, with its emphasis on a more economic approach and efficiency and use of neoclassical economics, fails to capture the reality of how firms make short-term choices.Footnote 56 He admits that taking into account short-term welfare effects may reduce the administrability of antitrust law and that policymakers will, therefore, have to rely on values that are outside the neoclassical market efficiency model. This leads him to conclude that antitrust will inevitably always have a noneconomic, or political, content. Van den Bergh and Camesasca argue that in EU competition law there is in reality no coherent discussion taking place about the system's objectives, although they hold the view that only efficiency and consumer welfare are appropriate normative goals of competition law and that ‘other objectives, such as market integration and protection of individual economic (business) freedom, may be fully legitimate but should be pursued by other legal instruments’.Footnote 57

In all, it is evident that there is both great variety and wide disagreement of views on the proper or actual goal of competition law. Against this backdrop, an exhaustive empirical study of what the institutions that apply and interpret competition law have to say greatly illuminates the debate and adds a conclusive authoritative voice.

2. Methodology: building an empirical investigation into the goals of EU competition law

To ensure consistent results, we employed a methodology regulating both matters of substance and matters of procedure. We note at the outset that our methodology was not guided by an initial hypothesis; our approach was data-driven, meaning that we designed the methodology without anticipating any particular outcomes. This allowed us to approach the research question with a clean slate, which we concluded was preferable, since our study was the first to statistically analyse EU institutions’ decisional practice and we erred on the side of neutrality.

In terms of substance, the challenge was to define the scope of the inquiry in a way that would encompass as many relevant goals and purposes as possible, appropriately grouped together; in terms of procedure the aim was to ensure that the search would be as exhaustive as possible to cover and organise all publicly available sources within the remit of the project.

We divided the methodological steps into global and goal-specific. The global methodology was applicable to all goals and purposes we catalogued, whereas goal-specific steps and principles applied complementarily only to the respective goal. This was necessary because the keywords corresponding to each of the seven goals we studied came with idiosyncratic meanings calling for pre-defined principles on how they should be handled. Competition law has been influenced by various disciplines, particularly economics, and so we needed to ensure that the keywords encountered in EU institutions’ decisions had the legal meaning competition law understands as it transpired through our literature review (see section 1 above). For the most part, this was not particularly problematic, because the concepts transplanted into competition law from other disciplines often intentionally retain their meaning (eg welfare and surplus mean the same in competition law and in economics). Where discrepancies occurred, we only included results that matched the legal definition of the keyword. For example, while ‘efficiency’ in economics has various definitions depending on whether one speaks of productive, allocative, or dynamic efficiency, in competition law, as a goal, it has the meaning of technical and economic progress as used in Article 101(3) TFEU (see below in this section and footnote 60).

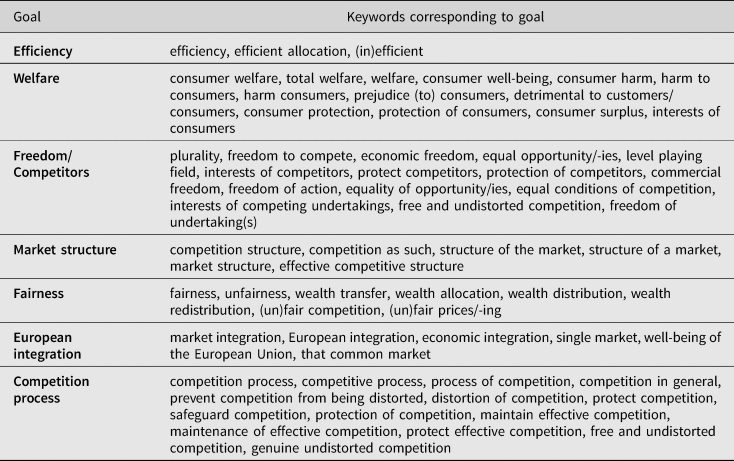

The project was based on full text keyword searches. The first step was to select the main goals and purposes we would be looking for and the corresponding keywords that would denote reference of those goals. For this, we first reviewed the literature (see section 1 above) and the relevant case law that was identified within as representative of discussing EU competition law's goals and purposes. Where there was disagreement in terms of which goal a certain keyword served, we made a value judgement based on a review of how the keywords were used in the case law and which goal(s) they seemed to be more closely associated with. Upon a first selection of goals and keywords, we ran iterative rounds of searches through Court of Justice decisions to ensure that the keywords were both exhaustive and correctly assigned to goals. In total, we catalogued seven main goals reflected in 74 keywords (Table 2).

Table 2. The main goals of EU competition law and corresponding keywords

Next, we used the keywords corresponding to the selected goals to search through the sources. We treated all text in decisions and opinions as equal (ie we did not differentiate between legal reasoning, obiter etc), on the assumption that the whole text of decisions and opinions contributes to their outcome (but see rule 2d in Table 5 below). Attempting to treat some parts of decisions and opinions as more influential or authoritative than others would introduce an unmanageable degree of subjectivity. For decisions by the Court, as well as for opinions of Advocate Generals, we used the Curia database. In total, we searched through 1,802 Court of Justice and General Court decisions and 485 opinions of Advocate Generals (Table 3). For the Commission's decisions, as the online search tool does not allow full text search, we had to download all decisions manually and search through the downloaded files.Footnote 58 We catalogued only those types of decisions that were likely to include a discussion on the goals and purposes of EU competition law: for Articles 101 and 102 TFEU, commitments decisions, interim measures, prohibitions, and (reasoned) rejection of complaints decisions, as well as Article 106(3) TFEU decisions only in so far as they included a discussion as to an infringement of Article 102 TFEU. On merger control we only reviewed Phase II decisions, under the same rationale. In total, we searched through 744 Article 101 TFEU decisions, 180 Article 102 TFEU decisions, 91 merger decisions, for a grand total of 1,015 Commission decisions (Table 3). For public speeches delivered by Commissioners for Competition, we relied on the Commission's online archives, from where we downloaded all available speeches.Footnote 59 We note, however, that many of the links to past speeches were broken, especially pre-2005. Therefore, while our results on speeches prior to 2005 are as robust as they can be given the availability of archival material, they are not as reliable as the rest. In total, we searched through 447 speeches (Table 3). We included speeches in our analysis, even though they do not reflect binding jurisprudential outcomes, because they provide a more informal and flexible platform for EU's enforcement branch to express what EU competition law is about and what they may wish to achieve through it, which we can use to calibrate and interpret our results. Indeed, as our results demonstrate in section 3 below, speeches, reflecting the Commission's public face, disproportionately emphasise goals such as welfare and fairness, which may resonate with the people more than market structure or efficiency. The grand total of the sources we searched was 3,749.

Table 3. Types and numbers of sources searched

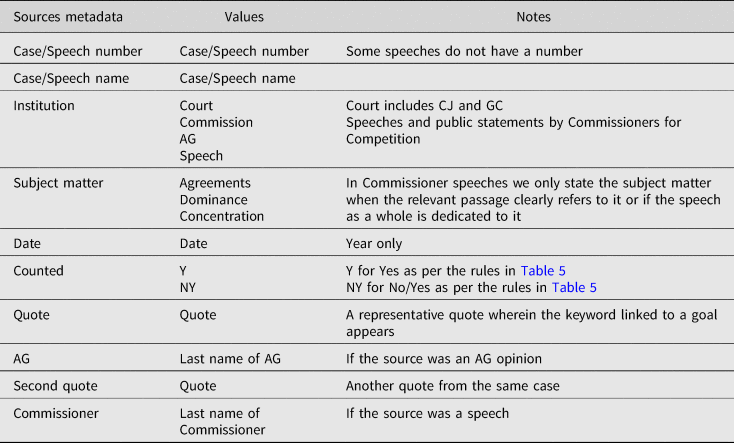

From the result lists as per above we went into each document, searched for the keyword, decided whether it related to the goals and purposes of EU competition law, and if so, we recorded the following metadata (Table 4):

Table 4. Recorded metadata for each documented source

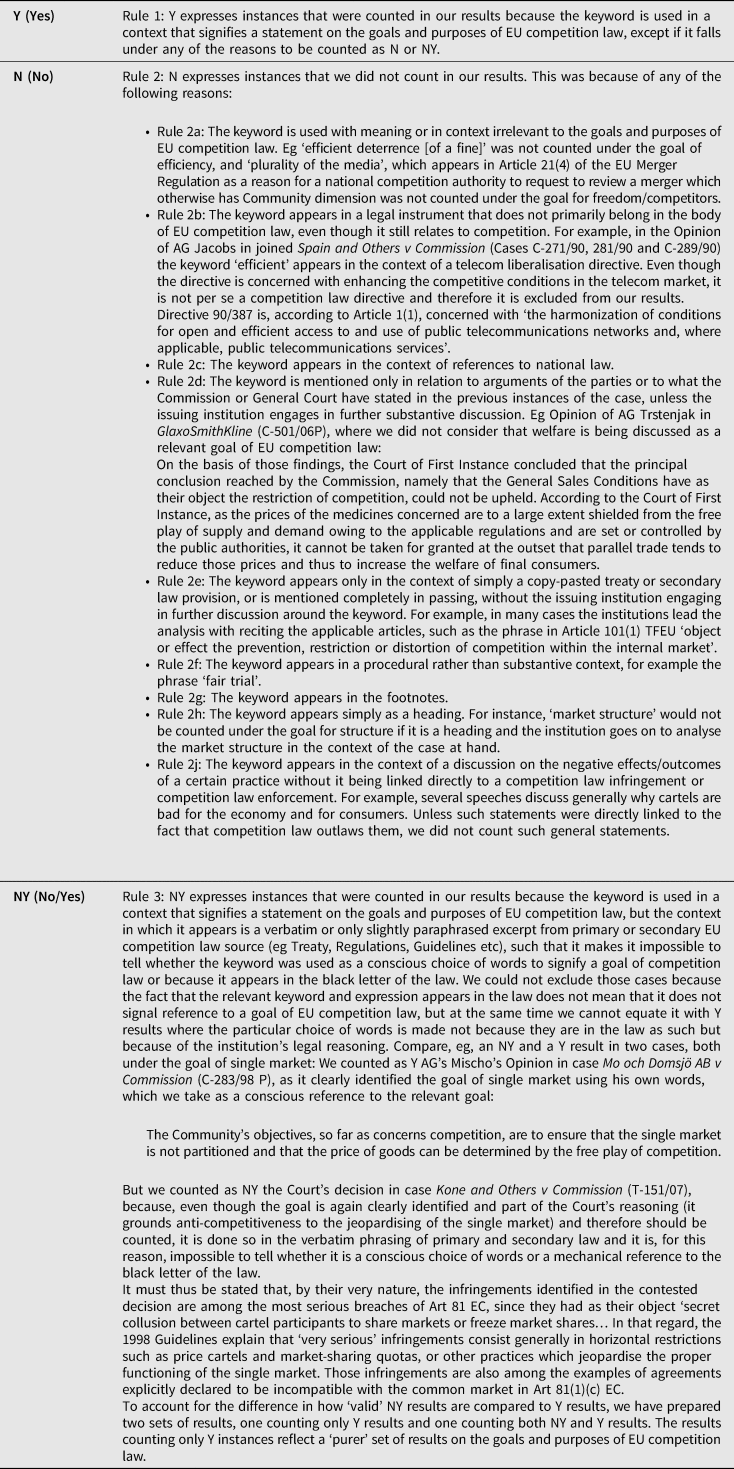

To decide whether the use of the chosen keywords signified a statement on the goals and purposes of EU competition law we distinguished between three possibilities as follows:

Table 5. Rules for deciding inclusion/exclusion of whether a source is counted as referencing a competition law goal

We also adopted the following global rules:

• Rule 4: Cases that have advanced through different instances (eg Commission case which was appealed to the GC and then to the Court of Justice) are counted separately, because a new decision is issued at every instance, unless Rule 2d applies.

• Rule 5: The same quote can contain keywords that refer to different goals and may be counted differently. For example, in Ambulanz Glöckner (C-475/99) the following quote signifies both the goal of integration (‘single market’) and the goal of structure (‘structure of competition’), but the goal of integration is counted as NY (Rule 13), whereas the goal of structure is counted as Y (Rule 17):

-

‘Thus, Community law covers any agreement or any practice which is capable of constituting a threat to freedom of trade between Member States in a manner which might harm the attainment on the objectives of a single market between the Member States, in particular by sealing off national markets or by affecting the structure of competition within the common market.’

-

• Rule 6: Multiple keywords grouped under the same goal are counted once, because they all signify the same goal. If some keywords are counted as NY or N and some as Y, Y prevails.

In addition to global rules, we adopted detailed goal-specific rules to account for the special features, meanings, and context of each of the selected goals. These are too detailed to describe here, but they can be found in the full report.Footnote 60 Some examples below can illustrate the need and function of the goal-specific rules. For instance, one of the rules specific to efficiency as a goal (Rule 12) was that we would not list sources (N) mentioning the keywords associated with efficiency when efficiency is used to express a specific benefit in a product, service or process, similar to eg security, quality, safety, robustness, speed, and not as a general proxy term for technical or economic progress. Eg in Transatlantic (94/980/EC):

In the Commission's view, price stability may constitute an objective within the scope of Art. 85(3) of the Treaty for the following reasons:

— stability of rates for scheduled services enables shippers to know reasonably far in advance the cost of transporting their products and therefore their selling price on the market of destination, whatever the time, vessel or conference shipowner involved,

— stability of rates enables shipowners to forecast their income more accurately and thus makes it easier to organize regular, reliable, adequate and efficient services.

We did, however, count sources (Y) where the keyword ‘efficiency/-ies’ appears as a shorthand for the Article 101(3) TFEU phrase ‘improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress’ (Rule 9 and see also Rule 3).

As another example, this time regarding the goal of competition process, Rule 24 stated that we count (Y) references to the old pre-Lisbon Treaty Article 3(1)(g)/(f) even if they quote the black letter of the law or slightly paraphrase it (ie Rule 2e did not apply), because Article 3(1)(g)/(f) expressly concerns itself with the goals of competition law, so referring to that article must be seen as a conscious choice to adopt the exact same goals mentioned in the article and to allow them to inform the specific application of competition law in the case. The text of old Article 3(1)(g)/(f) was as follows:

For the purposes set out in Art. 2, the activities of the Community shall include […] a system ensuring that competition in the internal market is not distorted.

This provision resulted, through paraphrasing, in including certain expressions such as ‘prevent competition from being distorted’ and ‘distortion of competition’, which appear as keywords corresponding to the goal of competitive process.

We close the methodology section with a note on an important caveat. Some competition law offences occur or are prosecuted more often than others (eg Article 101 TFEU cases compared to 102 TFEU cases), which can accordingly affect the occurrence frequency of the keywords encountered in the respective decisions, opinions, and speeches. This can skew results in favour of those types of cases (see also section 3(c) below). The bias, however, is only as strong as one expects certain keywords to be more associated with a certain type of offences/cases. While we do not rule out the possibility, we note that, if after all, certain types of offences/cases are more common, then competition law is, at least quantitatively, more concerned with correcting that type of market imperfections, and therefore more strongly serving the relevant goal associated with that market imperfection.

3. The goals of EU competition law: what do the practice and decisions of EU institutions say?

In this section we present the results we obtained and our interpretations thereof. Unless otherwise noted, the results below are based on the sources that were counted as Y (see above, section 2). By filtering out the less relevant sources designated as NY the presented results are the closest and most accurate representation of how the goals and purposes of EU competition law manifest themselves in the entirety of EU institutional practice.

Our results both corroborate longstanding theoretical and normative arguments, and break new ground. In doing so, they resolve scholarly disputes with empirical data, shed new light on patterns of institutional practice, and provide ample new data-based knowledge that can underpin future research. As the EU is one of the most – if not the most – activist antitrust jurisdiction in the world, it is only natural that it is looked to by other jurisdictions for inspiration, and that it also attracts ample introspective study. Our results help dissect EU competition law's goals and scope as a matter of practice, complementing, validating, or contracting normative approaches, through which process newfound clarity emerges.

(a) EU competition law is not monothematic but pursues a multitude of goals historically and today

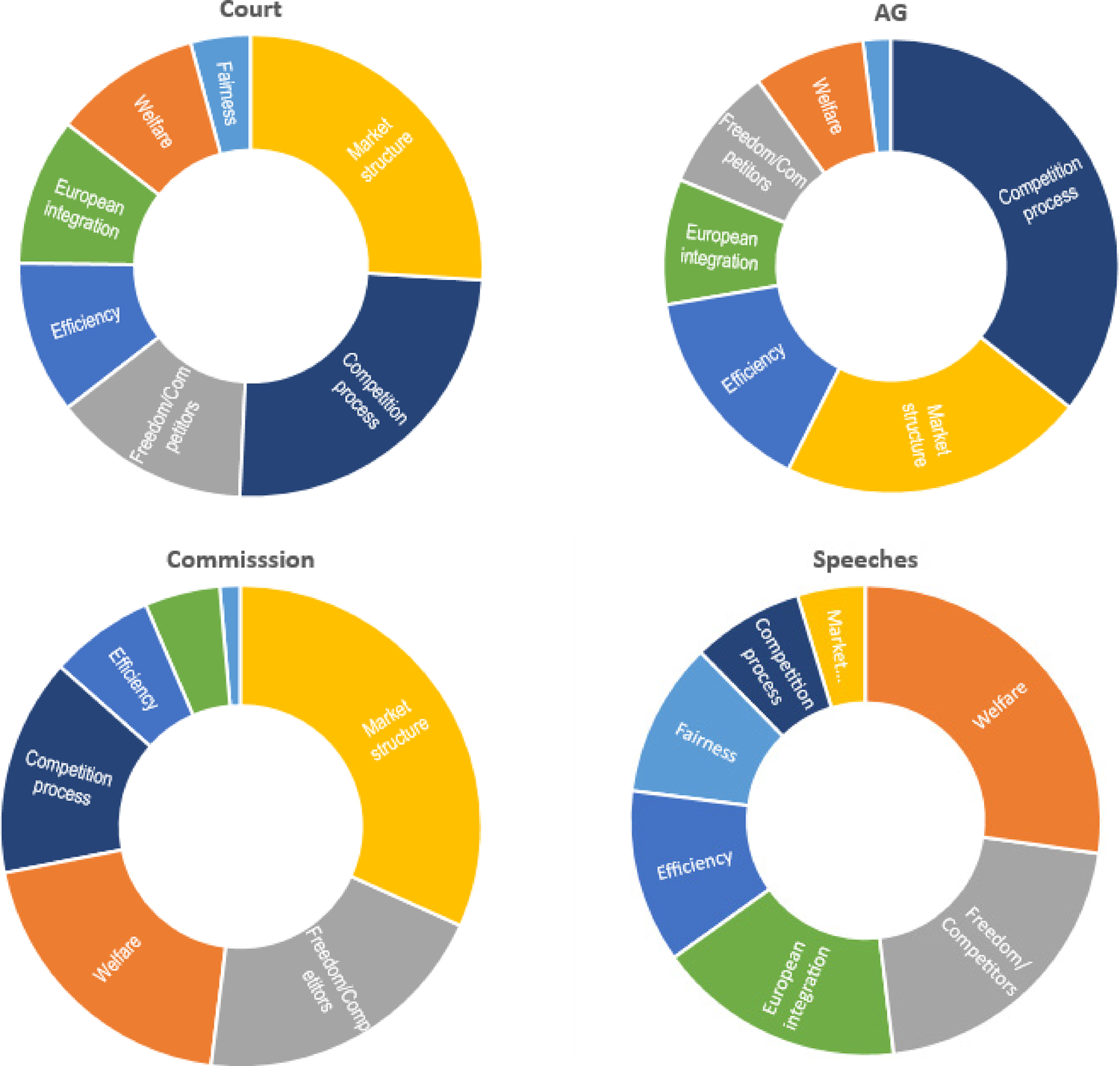

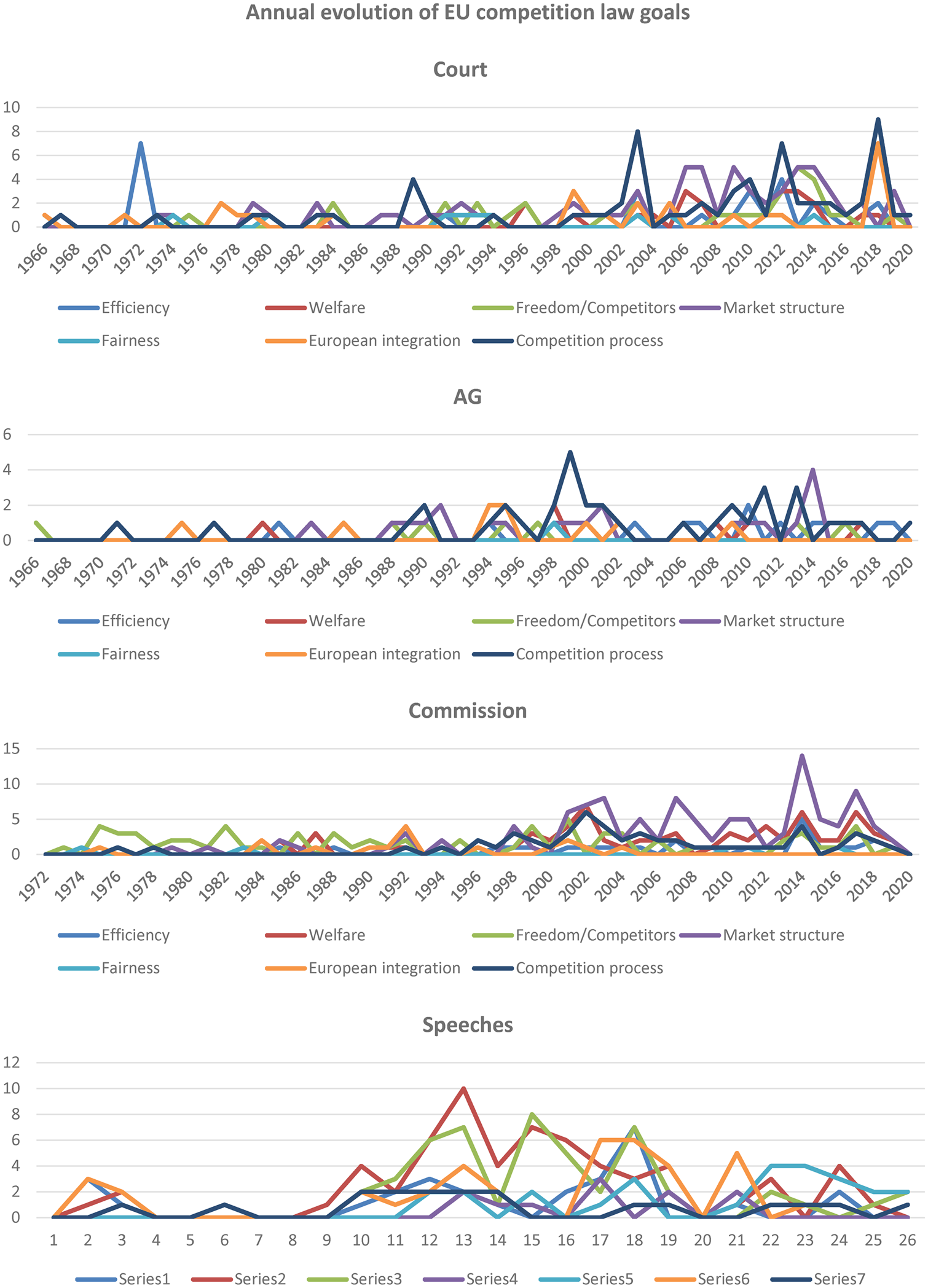

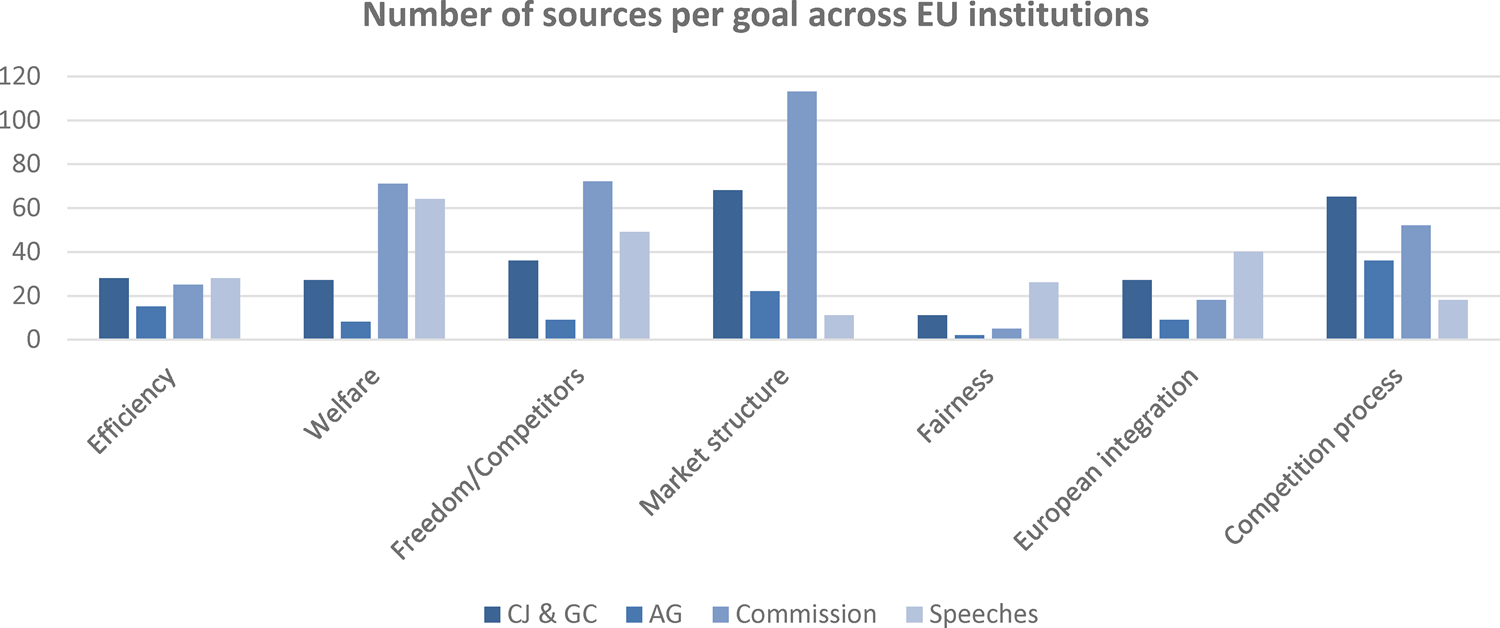

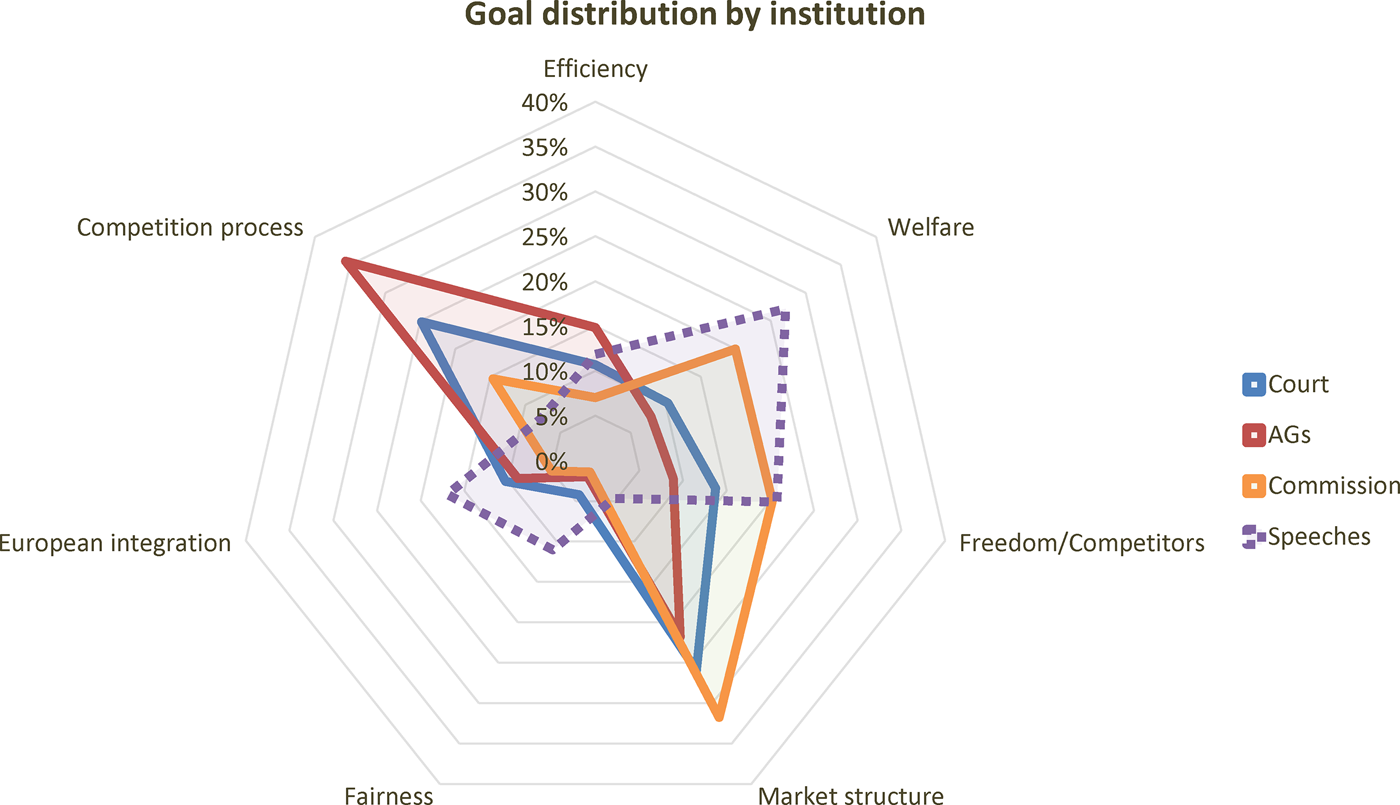

Institutional practice overwhelmingly confirmed that all seven of the overarching goals are represented to varying extents in the sources (Figure 1). What is more, all seven goals are present from the 1960s until today; in other words, goals are persistent even if their significance fluctuates with time. This is illustrated in the graphs below, which show the number of sources associated with a given goal on a year-to-year basis. All goals have a more than negligible presence in the decisional practice in case law and soft law (see also sections 3(b) and 3(c) below, and Figure 3). This dispels the myth that competition law is monothematic or that it is consistently concerned with only one main goal at the expense of others, as some scholars have normatively or positively argued.Footnote 61 While some goals may be more important than others, our results do not support the conclusion that, as a whole, competition law is only about one priority – whether welfare, efficiency, competition process or other. This also shows that scholars who argue for the inclusion of goals without rejecting the relevance of other goals are the ones closest to the empirical truth of EU competition law.Footnote 62

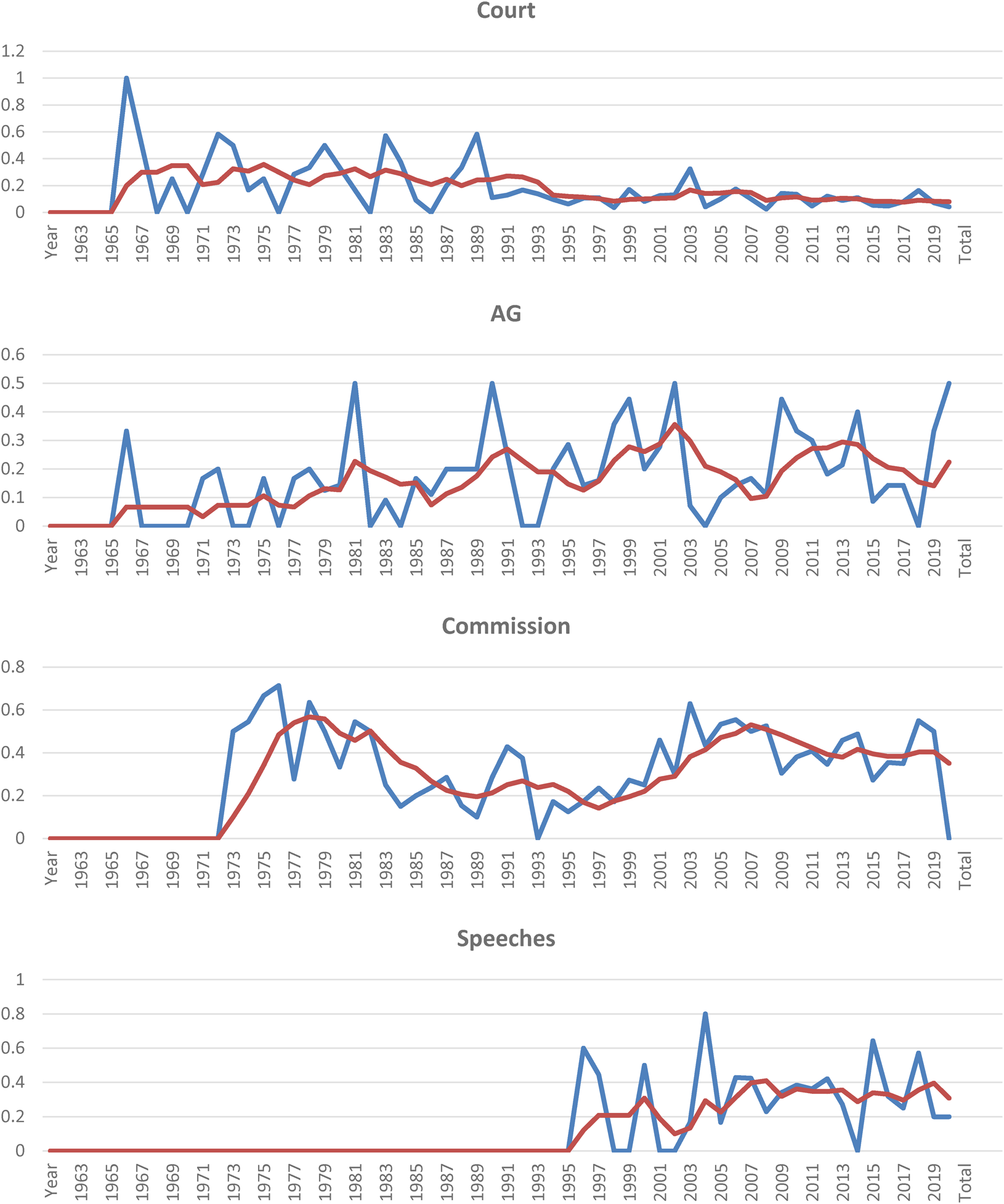

Figure 1. Number of sources per year, goal and institution. *2020 coverage only until February of that year

It is also interesting to note that the historical persistence of the goals of competition law suggests that they are integral to it rather than reflections of a given zeitgeist. One could expect a steady rise or fall of certain goals in response either to the influence of past case law or to the intellectual forces of the time. While weak signs of that are observable, our results do not seem to suggest that EU competition law is swayed by trends (more on that in section 3(b) below).

(b) Prior decisional practice and academic commentary do not seem to have consistent influence on future cases

A reasonable expectation would be that as new decisions and scholarly work come out on the goals of competition law, they affect future institutional practice. Our results do not confirm this intuition. We were unable to find consistent evidence of a reinforcement effect of prior case law or of external influences such as scholarly work. It is therefore likely that the decisional practice of EU institutions is guided more by what seem to be inherent dogmas of competition law and less so by trends. Advocate General Kokott in Post Danmark urged the Court of Justice to do exactly that, ie ‘not allow itself to be influenced so much by current thinking (‘Zeitgeist’) or ephemeral trends, but … have regard rather to the legal foundations [of] EU law’.Footnote 63

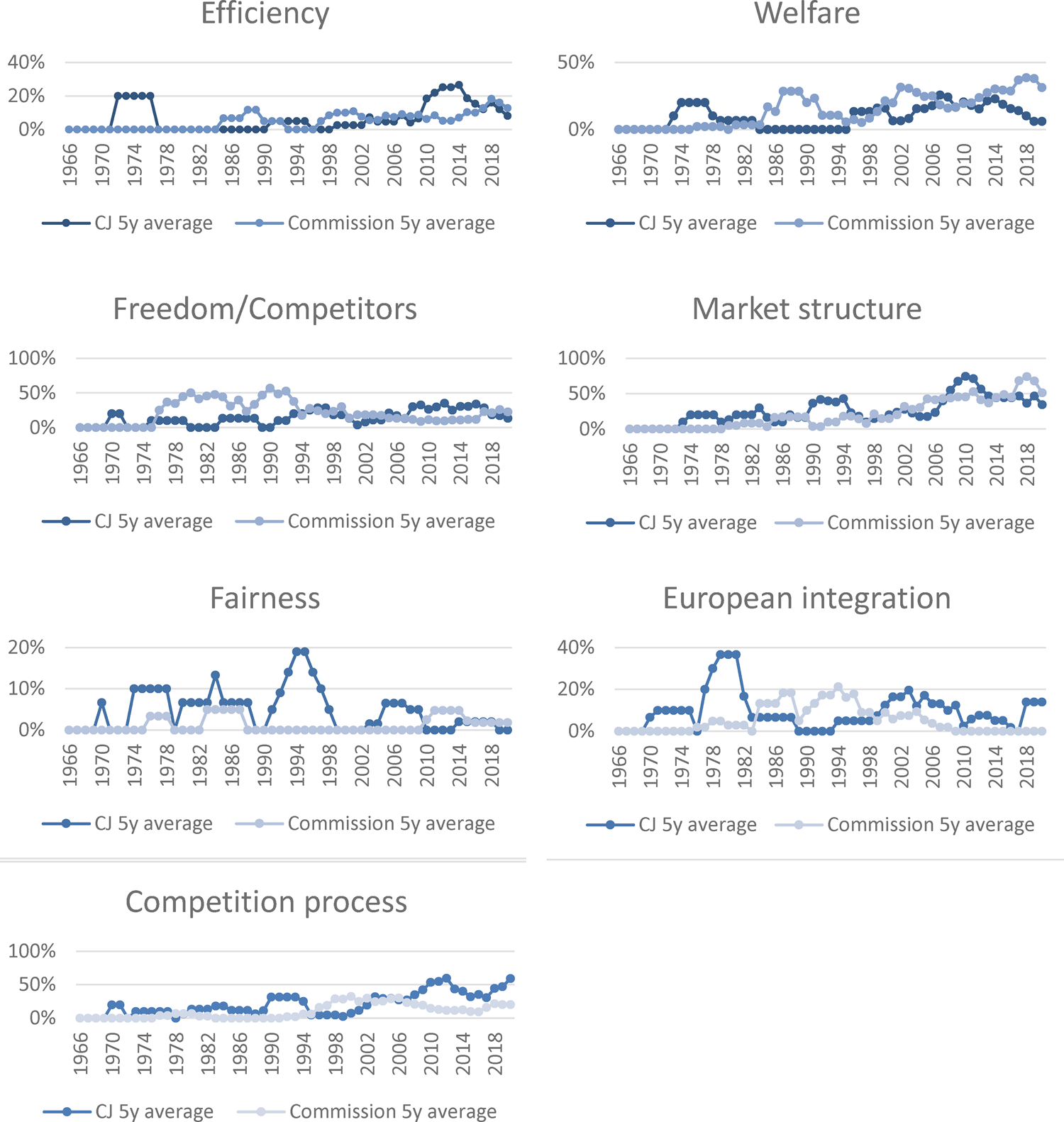

In terms of decisional practice, the obvious way to test this would be to observe the historical patterns of each goal evolution per institution. A steady change (increase or decrease) could indicate that a goal is increasingly being supported or phased out, and a flat curve after a change could indicate that once a goal has gained recognition it retains that status. Overall, we do not observe such consistent trends (Figure 2), and even when they appear (eg market structure), they may be explicable on the basis of other factors, such as an increase in the type of cases that touch on the relevant goals, rather than due to a reinforcement effect.

Figure 2. Five-year ratio averages of Court of Justice and Commission decisions

The other and more accurate approach we considered is to observe whether the trends noticed in Commission decisions are reflected in Court case law either contemporaneously or with a time lag of approximately five years. Contemporaneous mirroring could indicate a reaction to external influences, including academic work, whereas a time-delayed mirroring could indicate that the Commission's decisions that are appealed to the Court influence the Court's decisional practice. Either way, again the data do not seem to corroborate this hypothesis (Figure 2): fairness remains scarcely represented throughout; market structure and welfare are on the rise but the Commission's uptake comes a decade after that of the Court, and so it cannot be its driving force and it is unlikely that the two institutions react to the same external influence (eg scholarly work) with such a large time difference; and EU integration and the protection of competitors exhibit irregular patterns. The goals of competition process and efficiency are the only ones which exhibit a somewhat similar pattern of uptake, and with the Commission's uptake starting 5–10 years earlier than that of the Court. It is possible that the upward trend of efficiency and welfare beginning already in the mid-late 1980s (rather than in the late 1990s when the Commission moved to the ‘more economic approach’) can be explained by the growing popularity of the Chicago School, but on aggregate we would be reluctant to offer this as a reliable conclusion.

It is important to note that while our results do not corroborate the hypothesis of case law reinforcement or scholarly influence, they do disprove it either. It is likely that other forces are at play as well, and without isolating the various contributing factors, it is impossible to track, using our methodology, the reasons and influences for the observed trends.

Similar contemporaneous patterns could indicate reaction to external influences, while similar patterns with a time lag could indicate a reinforcement effect between Commission decisions that are appealed to the Court. With the exception of the goal of market structure, and to a lesser extent efficiency, there is no observed consistency, and therefore prior decisional practice and academic commentary do not seem to have consistent influence on future cases.

(c) EU competition law prioritises the process of competition rather than the outcome

Although, as mentioned, all goals are persistently present in the results and none is manifestly predominant, competition process and market structure are the ones that appear more frequently both in terms of percentage and in terms of absolute numbers, at least as regards the practice of EU institutions (ie excluding Commissioner speeches). These two goals are closely related to each other; they express the desire to protect a market structure that is built around an effective competitive process (see Table 2 for the keywords corresponding to these goals). EU competition law, therefore, seems to prioritise the process rather than the outcome (eg efficiency, welfare) under the belief that the process will, in turn, deliver the optimal outcomes.

A cautionary note is due here: because some goals seem to be more prevalent in certain types of cases and certain types of cases are more common in competition law enforcement the results can be skewed depending on the commonness of the type and subject matter of the cases, opinions and decisions. One example is the following quotation on the definition of ‘abuse’ from Hoffmann-La Roche (Case 85/76) (the quotation highlights that competition law aims at protecting the competitive structure of the market by outlawing conduct as abusive on the grounds that it distorts it):

… The concept of abuse is an objective concept relating to the behaviour of an undertaking in a dominant position which is such as to influence the structure of a market where, as a result of the very presence of the undertaking in question, the degree of competition is weakened and which, through recourse to methods different from those which condition normal competition in products or services on the basis of the transactions of commercial operators, has the effect of hindering the maintenance of the degree of competition still existing in the market or the growth of that competition.

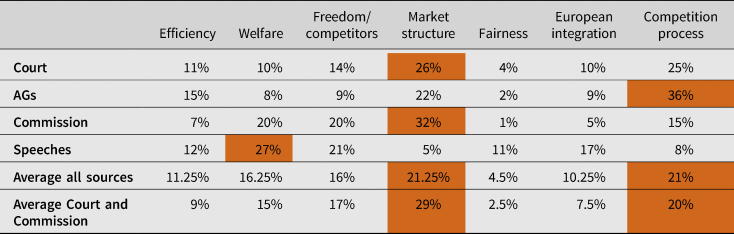

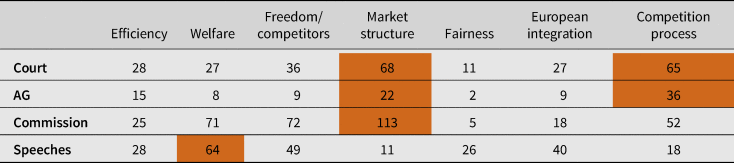

This quotation has appeared dozens of times in our results and it raises the absolute number of sources that reference market structure as a relevant goal. While we cannot account for the fact that certain types of cases are simply more numerous than others (at a minimum, there are a lot more cases involving Article 101 TFEU than Article 102 TFEU), looking also at the relative prevalence of goals within institutions’ decisional practice, ie the percentage distribution in Figures 3, 4 and Tables 6, 7, helps put things in perspective: percentage distribution shows what share of the total sources delivered by each institution corresponds to a given goal. This guards against assigning disproportionate importance to large absolute numbers of sources for a given goal, when in reality this is only so because a very large number of sources was delivered in total as well.

Figure 4. Distribution of sources per goal per institution in absolute numbers

Table 6. Percentage distribution of goals across institutions. It is evident that, taken together, the related goals of competition process and market structure are more prominently featured in the ‘hard law’ sources and Advocate General opinions.

Table 7. Distribution of sources per goal per institution in absolute numbers

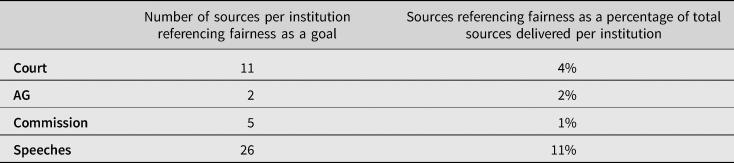

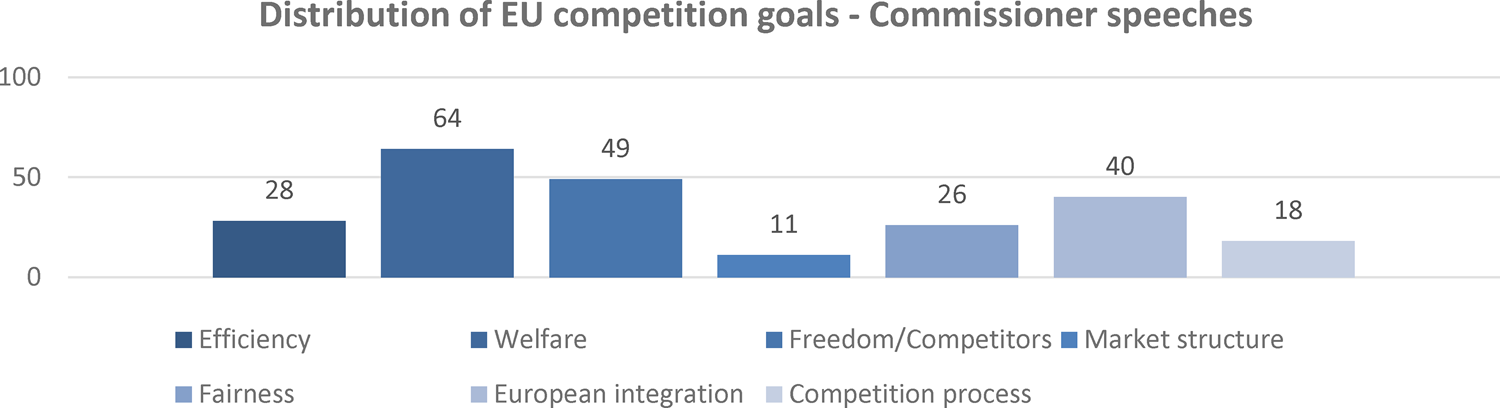

(d) Fairness, despite media popularity, does not fare highly in any EU institution practice

Fairness has been a popular buzzword in competition law circles recently and a commonly cited goal. Increasingly, the popular appeal of fairness is reflected in scholarly work too.Footnote 64 Our research shows that fairness is just that: a popular goal in the media, but not yet in decisional practice (Figure 3 and Tables 6, 8). Fairness is the least represented goal across all EU institutions, but it featured more prominently in Commissioner speeches, particularly thanks to Commissioner Vestager (see also section 3(e) below). We take that to mean that as a matter of actual legal practice fairness does not seem to be a determinative goal of competition law, but that it nevertheless is commonly promoted as such outside of strictly legal circles.

Table 8. Absolute number of sources and percentage out of total sources per institution referencing fairness as a goal

It is interesting to note that fairness's prominence would double if we included in the results the sources we designated as NY and which we normally exclude from the results presented here, as explained in section 2 above and the introductory paragraph of this section. An example of such instances is cases that reference verbatim the text of Article 102 TFEU on unfair prices or trading conditions. Even then, however, fairness remains a marginal goal (Table 9). We cannot rule out the possibility that decisional practice has not yet had the time to catch up with scholarly analysis that supports fairness. After all, fairness has only taken centre-stage in academic writing in the past decade (see section 1 above). But equally, the incorporation of fairness principles in legislation that has dual antitrust-regulatory nature – notably the Commission's Digital Markets Act – may commingle the role of fairness in competition law and in market regulation. While we pass no judgement as to whether that is desirable, we note that it may artificially raise the profile of fairness in competition law decisional practice.

Table 9. Number of sources that reference fairness as the relevant goal counted as ALL (NY & Y) and only as Y. Even under the broader set of results (ALL), fairness still ranks low as a goal. See Table 5 for explanation on Y and NY.

(e) The Commission has different priorities than the Court and Advocate Generals and Commissioner speeches express yet different priorities too

Figure 3 and Table 6 further demonstrate that the Commission and the Court (including Advocate Generals) assign different relative weight to different goals. While it is true that the process of competition and market structure feature prominently in all of their practice (see section 3(c) above), there is little agreement between them otherwise. The Commission assigns more value to welfare and to the protection of competitors and commercial freedom but less value to efficiency than the Court and Advocate Generals (Figure 5). And even in terms of the competitive process, the Commission is only half as concerned with that goal compared to the Court and Advocate Generals. It is risky to hypothesise on the reason, but the Commission's emphasis on the protection of competitors and commercial freedom may be explained on account of its multifarious role in the EU competition law system. Not only is the Commission both a prosecutor and an adjudicator, but it also expresses the EU's political priorities.Footnote 66 As such it may be more susceptible to lobbying (by disadvantaged competitors), which infiltrates its enforcement activity. We offer this explanation with caution, because despite it being popular,Footnote 67 research remains inconclusive.Footnote 68 By contrast, the Court of Justice is to be seen as a purely adjudicatory and strictly independent body, making it less susceptible to considerations external to the law. Speeches express yet different priorities, with welfare dominating the speeches’ goal list and fairness being featured at a higher rate in speeches than in any other type of source. This is perhaps natural, because Commissioners for Competition want their speeches to resonate with the public and fairness and welfare are buzzwords that can help achieve that goal.

Figure 5. Relative commonness of goals per institutionFootnote 65

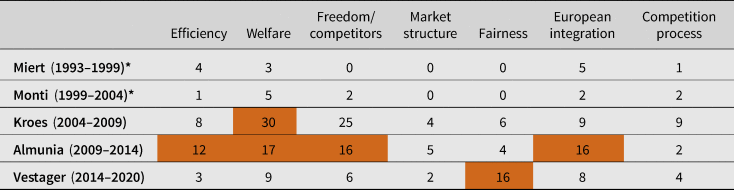

(f) Different Commissioners seem to emphasise different goals during their terms, with Vestager promoting fairness and Kroes promoting welfare

It is only natural to expect that Commissioners have their own agendas, priorities, and sensibilities, and that this will be reflected in their speeches and advocacy. Indeed, our results indicate that certain Commissioners, as it transpires through their speeches, emphasise some goals more than others (Table 10 and Figure 6). For example, it is clear that Commission Vestager is a strong advocate of fairness, whereas Commissioner Kroes was concerned predominantly with welfare. Besides personal priorities, the historical context of their office terms may help to explain these results. Kroes, for instance, was in office just before a landmark legislative package on telecom liberalisation was passed (after her term as Commissioner for Competition, she became Commissioner for Digital Agenda), and many of her speeches reflect the combined contribution of competition and regulation as tools to safeguard and maximise welfare.

Table 10. Number of speeches per goal per Commissioner. *Miert's and Monti's results are limited due to partial unavailability of their speeches.

Figure 6. Distribution of EU competition goals in speeches by Commissioners for Competition

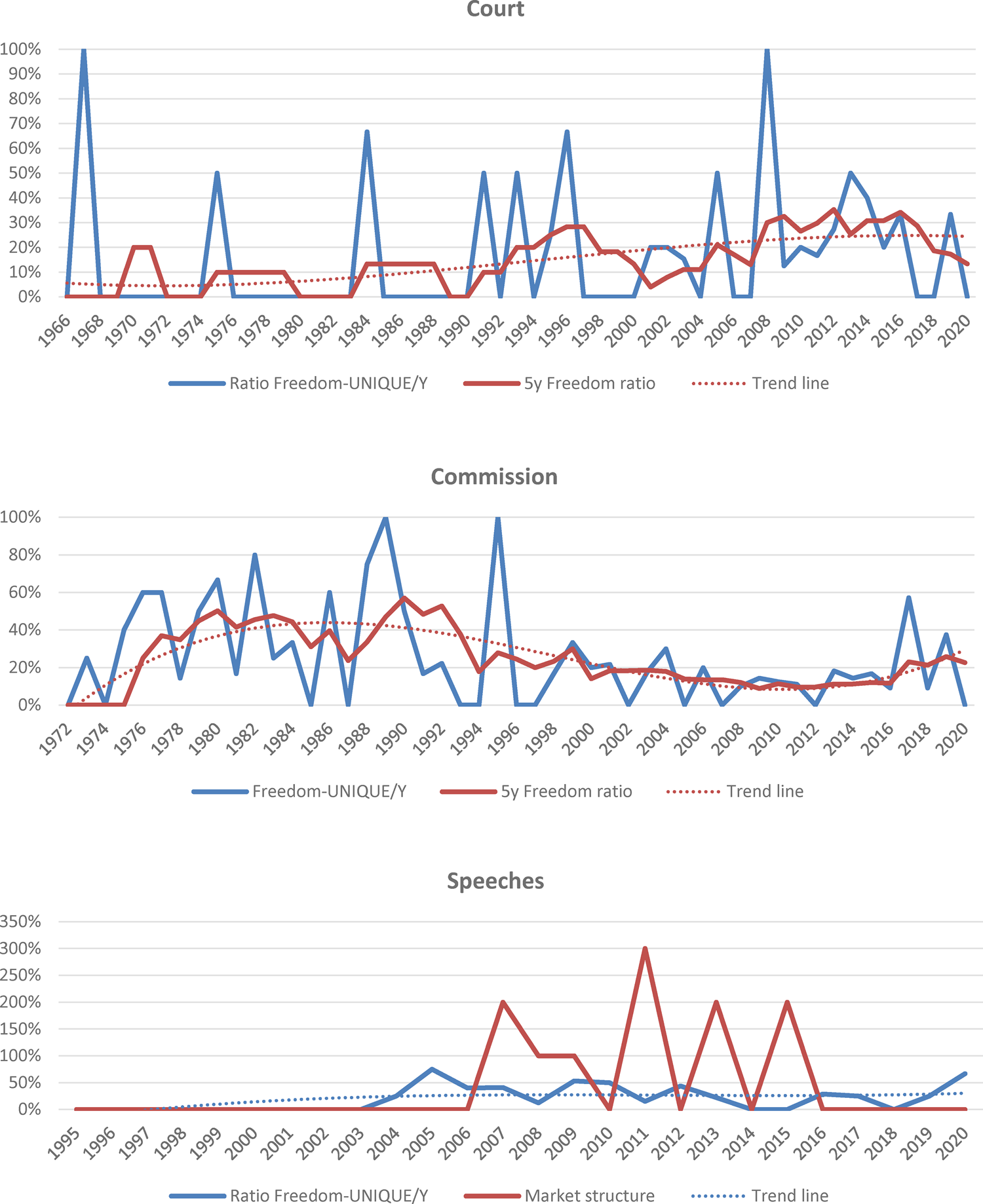

(g) Ordoliberalism still lingers and may be on the rise again

A risky, but not unsubstantiated, inference from the data is that the goals that can be attributed to the ordoliberal tradition, such as commercial freedom, level playing field, and the protection of competitors (see Goal 3 in Table 2), seem to be on the rise of late. They still do not fare very highly overall, but it is worth noting the constant increase in the share of Court decisions that reference these goals, effectively doubling in rate from the early 1990s to today, and the recent, post-2013, rise in Commission decisions as well, after a period of decline which itself succeeded a period of very high rates of representation of such goals in Commission decisions (the five-year average exceeded 40% of Commission decisions in the mid-80s) (Figure 7). The trend is reflected in Commissioner speeches as well, with those goals retaining a steady share therein starting in the mid-2000s.

Figure 7. Sources referencing ordoliberal goals per institution. Ordoliberal goals (Goal 3 in Table 2) are on the rise in Court decisions, and in Commission decisions since 2013 after a dip in the last 20 years. In speeches, ordoliberalism is reflected at steady rates.

(h) Steady to increased discussion of competition law goals over the years, with Commission leading the increase, perhaps in response to the ‘more economic approach’

While in absolute numbers the sources that reference the goals of EU competition law have increased over the years (Figure 1), so has the total number of sources too. To determine whether the discussion of competition law goals has in fact increased, we calculate the ratios of sources that reference competition goals to total numbers per year. Our results indicate that, overall, the sources referencing competition law goals have only moderately increased, except in that case of the Commission, which starting in the early 2000s has doubled the share of decisions wherein it references the goals of competition law (Figure 8). Advocate General opinions and speeches show a more modest increase, whereas the Court shows a steady trend since the early 1990s and a decrease compared to the earlier years (Figure 8). It may be the case that the adoption of the more economic approach in the late 1990s urged the Commission to better justify its reasoning, as part of which effort it started referring to the goals of competition law as guiding principles.

Figure 8. Shares and five-year averages of sources referencing goals relative to total sources. Ratios (blue) and five-year averages (orange) of the sources referencing competition law goals to total sources. A mostly steady to upward trend is noticed, except for the Commission, which shows a doubling of rate since the early 2000s. See also Table 6.

Conclusion: history as a guide for the future of competition and EU law

Our comprehensive empirical research documents thoroughly the history and evolution of EU competition law – one of the most important EU law policy areas, where the Commission enjoys significant and rather unique powers of enforcement:Footnote 69 the competence lies exclusively with the EU,Footnote 70 and the substantive law is fully harmonised. The insights we derived tell us a lot about EU competition law's historical application from 1962 through to 2020, but they also allow us to make safer predictions as to the future of EU competition policy and reflect on general EU law.

When it comes to the future of competition law, we think it safe to assume that the goals we have identified will continue to be relevant. We expect that the relative importance of goals might fluctuate, depending on the types of cases that are pursued by the Commission and end up in the Courts as appeals, or as preliminary rulings from national courts. As our research demonstrates, competition law has shown remarkable flexibility over the years, but also considerable resilience regarding goals. That said, we also think it likely that new goals will enter the discourse and rise in prominence with time. A number of ‘contemporary’ goals are already prominent in the academic debate, and they are also being discussed by the current Commissioner for Competition, Executive Vice-President Vestager, and finding their way through national enforcement of competition law. Three emerging goals are environmental protectionFootnote 71 and sustainability,Footnote 72 privacy,Footnote 73 and workers’ protection and labour rights.Footnote 74 Using our database, we have already performed preliminary research on these goals and there is indeed decisional practice and case law supporting them. It is our intention to expand our research to include these goals too. Normative arguments in favour of subordinating certain goals under others, claiming that some goals can be direct whereas others ought to be achieved indirectly through the direct ones – as for example interpreting the welfare standard in a way that incorporates other goals – are likely to persist. From a positivist legal perspective, our research shows that no goal has ever been predominant and no goal has ever subsumed other goals; we do not think that will change. Thus, the contemporary goals we have in mind are likely to end up being goals of EU competition law in their own right, where those goals are also goals of the EU. In fact, that may be an EU constitutional law requirement that follows from the Treaties.Footnote 75

Competition policy is one of the most important generalist tools the EU has for regulating the conduct of market participants and, as we saw, also explicitly pursues a goal of integrating the single market. Whereas other areas of EU law, for instance free movement case law, have been pivotal in constructing, describing, and understanding the nature of EU law and the EU itself,Footnote 76 competition law has been hitherto somewhat missing from the narrative. We think that our research could change that, by providing material for reflection on the bigger EU law questions regarding the EU's internal market and economic constitution, such as what it is for, and who it is supposed to serve. Based on our findings, we think that EU competition law shows the likely relevance of broader goals for other EU law policies, not least state aid, the internal market, consumer protection, external trade, and the EU's current industrial policy of digital transformation and the European Green Deal. Forming part of EU law that applies to companies, competition law also shows the extent to which EU private law might become constitutionalised, requiring that companies not only do not contravene, but also promote, through their market conduct, human and labour rights, and other public policy goals.