No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

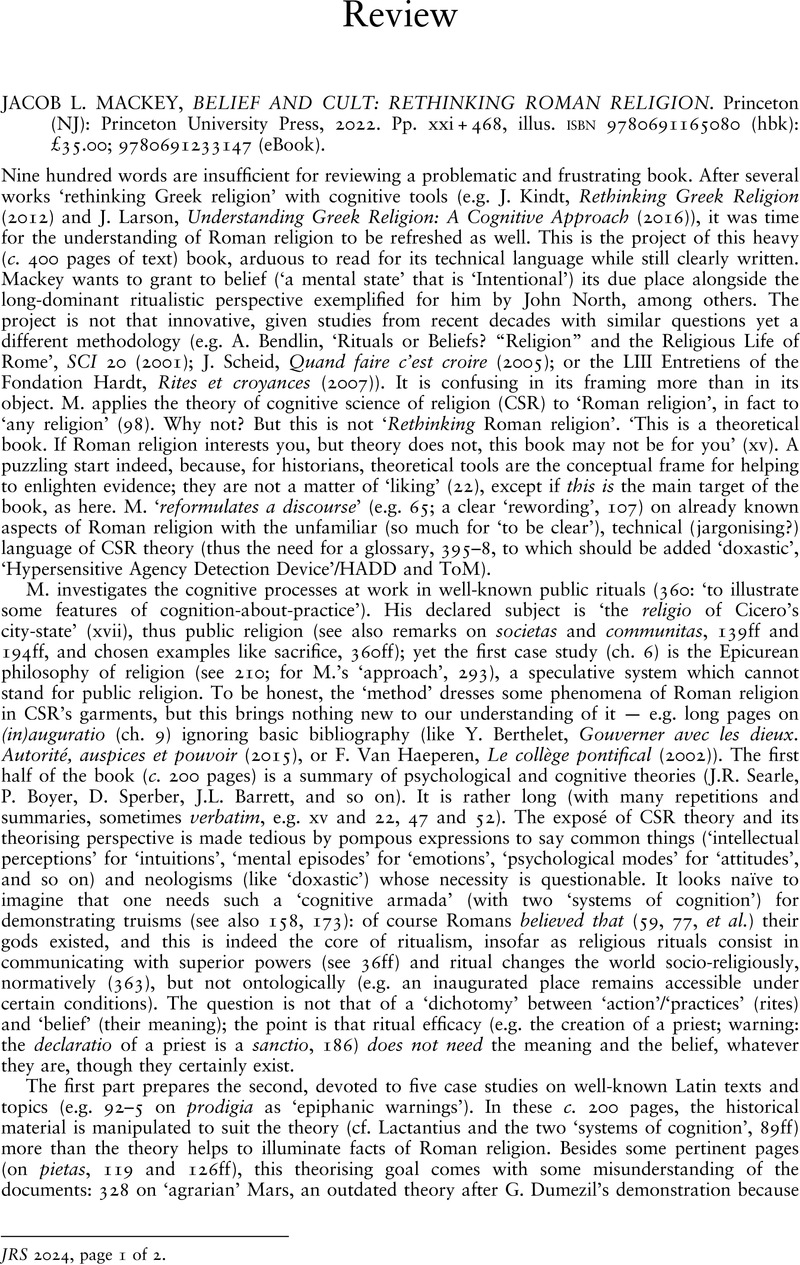

JACOB L. MACKEY, BELIEF AND CULT: RETHINKING ROMAN RELIGION. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 2022. Pp. xxi + 468, illus. isbn 9780691165080 (hbk): £35.00; 9780691233147 (eBook).

Review products

JACOB L. MACKEY, BELIEF AND CULT: RETHINKING ROMAN RELIGION. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 2022. Pp. xxi + 468, illus. isbn 9780691165080 (hbk): £35.00; 9780691233147 (eBook).

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2024

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies