Childhood anxiety disorders are common, affecting 5-10% of children. Reference Costello, Angold, Burns, Stangl, Tweed and Erkanli1-Reference Keller and Baker3 As well as disrupting children's social, emotional and academic development, Reference Silverman, Ginsburg, Hersen and Ollendick4-Reference Barmish and Kendall7 they present a risk in later life for further psychological disturbance, such as mood disorders and substance misuse. Reference Judd8,Reference Perugi, Frare, Madaro, Maremmani and Akiskal9 Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is effective and has been recommended as the treatment of choice, Reference James, Soler and Wetherall10,Reference Cartwright-Hatton, Roberts, Chitsabesan, Fothergill and Harrington11 however CBT is resource-intensive and is not accessed by many children who could benefit. Reference Canino, Shrout, Rubio-Stipec, Bird, Bravo and Ramirez12,Reference Farmer, Stangl, Burns, Costello and Angold13 One way of increasing access to psychological services is to adopt a ‘stepped care’ approach to treatment delivery Reference Marks, Mataix-Cols, Kenwright, Cameron, Hirsch and Gega14,15 in which brief, relatively simple, first-line treatments are routinely administered to service users with a relatively good prognosis, and more intensive treatments are reserved for those who do not respond to the first-line treatment and those whose prognostic profile indicate that they require more specialist input. An immediate challenge in the field of child anxiety is to develop and evaluate forms of CBT suitable for such low-intensity, first-line delivery. Guided parent-delivered CBT is a possible low-intensity treatment that could improve access to psychological interventions for children with anxiety. A number of studies have shown significant reductions in child anxiety when CBT interventions are delivered via parents, Reference Mendlowitz, Manassis, Bradley, Scapillato, Miezitis and Shaw5,Reference Thienemann, Moore and Tompkins16,Reference Cartwright-Hatton, McNally, Field, Rust, Laskey and Dixon17 suggesting that a first-line treatment could be delivered via parents. Furthermore, promising evidence is already emerging of impressive clinical gains using low-intensity CBT for child anxiety delivered by parents guided by therapists, Reference Rapee, Abbott and Lyneham18-Reference Lyneham and Rapee20 but the efficacy of this approach in UK healthcare settings has not as yet been systematically evaluated. In addition, the degree of guidance necessary remains unclear, Reference Lyneham and Rapee20,Reference Gellatly, Bower, Hennessy, Richards, Gilbody and Lovell21 as does the level of therapist training required for good child outcomes. In service delivery models, there is typically an assumption that the competencies required to deliver low-intensity interventions are different from those needed to deliver high-intensity interventions, with fewer qualified staff typically assigned to deliver low-intensity interventions. 15 However, no studies have specifically addressed whether level of therapist training is a predictor for treatment outcome for guided CBT treatment.

The current trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy of two versions of low-intensity, guided parent-delivered CBT for the treatment of childhood anxiety: ‘full guided CBT’, with weekly therapist contact over 8 weeks, and a ‘brief guided CBT’ intervention, with fortnightly therapist contact over the same period. By comparing versions of guided CBT with varying levels of therapist contact to a wait-list control group, we aimed to clarify the level of guidance required for this approach to be effective. In addition, we aimed to explore whether the professional background of the therapist is related to child treatment outcome. Since the presence of parental anxiety disorders has been found to be associated with less favourable child treatment outcomes from more intensive CBT treatments, Reference Bodden, Bogels, Nauta, De Haan, Ringrose and Appelboom22,Reference Cobham, Dadds and Spence23 we focused delivery of this low-intensity approach to a group with a relatively favourable prognosis, i.e. those children with a current anxiety disorder in the context of no current parental anxiety disorder. The current study, therefore, included only children with anxiety whose primary carer did not have a current anxiety disorder. In line with other major trials for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders, Reference Walkup, Albano, Piacentini, Birmaher, Compton and Sherrill24 we included children with varied primary diagnoses of child anxiety disorders because of the similarities in the underlying theories of maintenance of these disorders and their common comorbidity. Reference Reynolds, Wilson, Austin and Hooper25 Primary diagnoses included generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder/agoraphobia and specific phobia.

Method

Participants and recruitment

The study was conducted within the Berkshire Child Anxiety Clinic (BCAC), a specialist clinic for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders allied to the local child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS), which is jointly operated by Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences of the University of Reading. Ethical approval for this trial was granted by the Berkshire Research Ethics Committee (reference: 07/H0505/157), as well as by the University of Reading Research Ethics Committee. The trial was registered with ISRCTN (trial registration number: ISRCTN92977593). To be eligible for inclusion, potential participants had to agree not to engage in any other psychological intervention during the course of the study, and they had to meet the following criteria:

-

(a) child aged 7-12 years

-

(b) child meets criteria for primary diagnosis, according to DSM-IV, 26 of generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder/agoraphobia or specific phobia

-

(c) child does not have a significant physical or intellectual impairment (including autism spectrum disorders)

-

(d) if either child or primary carer has current prescription of psychotropic medication, the dosage has to have been stable for at least 1 month with agreement to maintain that dose throughout the study

-

(e) primary carer available to attend treatment

-

(f) primary carer does not have a current DSM-IV anxiety disorder or other severe mental health difficulties (e.g. severe major depressive disorder, psychosis, substance/alcohol dependence)

-

(g) primary carer does not have a significant intellectual impairment.

Participants were recruited from April 2008 to December 2010 from referrals made to BCAC from primary and secondary care. Assessments were completed between April 2008 and December 2011. Following confirmation of eligibility and informed consent, participants were randomised to one of the three groups using the centralised telephone randomisation service at the Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford. The randomisation process included a minimisation algorithm to ensure balanced allocation of participants across treatment groups for the following potential prognostic factors: child age, child gender, type of child anxiety disorder, and baseline severity of child's anxiety disorder.

In total, 552 children were referred to the BCAC during the trial recruitment period. Of these, 358 were excluded (36 declined to participate and 322 did not meet the inclusion criteria; 214 because of the presence of parental anxiety disorder). The remaining 194 were randomised: 64 to full guided parent-delivered CBT, 61 to brief guided parent-delivered CBT, and 69 to the wait-list. Outcome assessments were carried out post-treatment with 159 families, with 14 families (22%) lost to follow-up from the full guided CBT group, 15 (25%) from the brief guided CBT group, and six (9%) from the wait-list group. Eighty-seven families from the two guided self-help groups completed a 6-month follow-up assessment (i.e. 70%; see Fig. 1).

Procedures

All 7- to 12-year-old children referred to the BCAC and their primary carer were systematically assessed to establish suitability for the trial and to obtain baseline measures of child anxiety. For the majority of families (98%) the primary carer was the mother (mother as primary carer n = 190; father as primary carer n = 4). Where eligibility was confirmed, the family was invited to participate in the trial and, where consent was obtained, the family was randomly allocated to one of the three groups. Families allocated to one of the two guided CBT groups were sent copies of a self-help book Reference Creswell and Willetts27 and were assigned to a therapist on the basis of availability. Nineteen therapists, with varying levels of experience, were responsible for initiating contact with their allocated families and supporting them through the course of the treatment. Families allocated to the wait-list were informed of this fact via telephone and sent a confirmation letter. These families were asked to refrain from starting any other intervention for their child's anxiety for the next 12 weeks. Children were reassessed post-treatment by an assessor masked to treatment allocation. Following the post-treatment reassessment, families from the wait-list who still required treatment were offered guided parent-delivered CBT.

Families who declined to participate in the trial (n = 31), and those who requested or required additional support following completion of guided parent-delivered CBT (n = 5) or after the 6-month assessment (n = 7), were offered 12-week individual child CBT or referred to CAMHS, depending on the needs of the child.

Intervention

The intervention was a guided parent-delivered CBT treatment for children with anxiety. Parents were given a self-help book Reference Creswell and Willetts27 and received one of two forms of therapist support: ‘full guidance, which consisted of weekly therapist contact over 8 weeks, involving four 1-hour face-to-face sessions and four 20-minute telephone sessions (i.e. about 5 hours and 20 minutes of therapist guidance); or brief guidance, which consisted of fortnightly therapist contact over 8 weeks involving two 1-hour face-to-face sessions and two 20-minute telephone sessions (i.e. about 2 hours and 40 minutes of therapist guidance). Both face-to-face and telephone sessions were audio recorded to allow for checks of treatment adherence. The structure and content of the treatments are described in Table 1. Parents completed homework tasks between sessions, both independently and with their child. The role of the therapist was to support and encourage parents to work through the self-help book, rehearse skills and to problem solve any difficulties that arose.

Therapist experience

The 19 therapists who delivered the two forms of guided CBT had varying levels of clinical training and experience. They were categorised as either having ‘some clinical experience’ or being ‘novices’. Therapists in the ‘some experience’ group (n = 10) were either currently enrolled on a clinical training course or had previous experience of working with clinical populations. Therapists in this category included clinical psychology trainees (n = 2), CBT diploma students (n = 3), a trainee CBT therapist (n = 1), trained clinical psychologists (n = 3) and a psychiatrist (n = 1). Therapists in the ‘novice’ group (n = 9) did not have any previous experience of using CBT techniques or of working with clinical populations. Therapists in this category included assistant psychologists (n = 5), psychology postgraduate students (n = 3), and a psychology graduate (n = 1).

Fig. 1 Participant flow, randomisation and withdrawals at each stage of the study.

CAMHS, child and adolescent mental health service; CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder. a. Two people completed assessment 3 who did not complete assessment 2.

Therapist training and adherence to treatment delivery

All the therapists received an implementation manual (available from the authors on request) to accompany the self-help book and attended a training day on how to deliver the intervention. The training day included a mixture of presentations, discussion, group activities and role plays. Therapists received weekly, 2-hour group supervision with a clinical psychologist (K.T.). The audio-recorded treatment sessions were listened to by the clinical supervisor at regular intervals to check for adherence to treatment delivery. A random subsample of audio recordings of treatment sessions (n = 60) were coded for treatment adherence by independent raters (psychology graduates) on five-point scales (from 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘a great deal’) reflecting the depth and accuracy of therapist adherence to the manual in terms of treatment process (e.g. a collaborative approach between therapist and parent) and session content (i.e. specific material covered and exercises completed). A subsample of 20 therapy sessions were double coded and interrater reliability for total scores on all scales was found to be good (intraclass correlation (ICC) 0.88-0.89). Internal consistency of coded items within each scale was also acceptable (α = 0.71-0.87). Over 65% of therapy tapes were rated as showing the highest levels of adherence (rating 3 or 4 on a 0-4 scale) on 14 of the 16 items. The two items where fewer therapy tapes were rated as showing the highest levels of adherence were both relating to treatment process; inviting items for agenda (43% rated 3 or 4) and setting complete homework tasks (47% rated 3 or 4).

Measures

Measures of improvement in child anxiety status

Change in diagnostic status was assessed using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS), child and parent version, Reference Silverman and Albano28 administered at all assessment points by one of ten independent assessors masked to treatment condition. As is standard, where children met criteria for a diagnosis, a clinical severity rating (CSR) was allocated from 4 to 8. The pre-treatment diagnosis with the highest CSR was classed as the primary diagnosis. For each assessor, the first 20 interviews were discussed with a consensus team led by an experienced diagnostician (L.W.). After 20 ADIS assessments had been double coded by the consensus team, reliability was formally checked and raters were required to be reliable at a kappa/intraclass correlation of 0.85 before being considered reliable. Once reliability had been achieved, every sixth independent assessment was discussed with the consensus team to prevent rater drift. Overall interrater reliability for the assessor team was excellent (child-report diagnosis: kappa = 0.98; CSR: ICC = 0.98; parent-report diagnosis: kappa = 0.98; CSR: ICC = 0.97)

Table 1 Structure and content of the treatments

| Full guided parent-delivered CBT | Brief guided parent-delivered CBT | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Face-to-face session (1 h): | Face-to-face session (1 h): |

| • introduction to anxiety | • introduction to anxiety | |

| • discussion of possible causal and maintaining factors, and the and the implications for treatment |

• discussion of possible causal and maintaining factors, implications for treatment |

|

| • discussion of how to identify child anxious thoughts and challenge them |

• discussion of how to identify child anxious thoughts and challenge them |

|

| Week 2 | Face-to-face (1 h): | No contact with therapist |

| • introduction to cognitive restructuring and practice | ||

| • discussion of parental responses to anxiety | ||

| Week 3 | Telephone session (20 min): review tasks | Face-to-face session (1 h): |

| • discussion of parental responses to child anxiety | ||

| • devise a step-by-step plan to aid graded exposure | ||

| Week 4 | Face-to-face (1 h): devise graded exposure plan | No contact with therapist |

| Week 5 | Telephone session (20 min): review tasks | Telephone session (20 min): discuss problem-solving |

| Week 6 | Telephone session (20 min): review tasks | No contact with therapist |

| Week 7 | Face-to-face (1 h): | Telephone session (20 min): discussion of how to continue helping their child |

| • introduction to problem-solving and practice | ||

| • review progress | ||

| • discussion of how to continue helping their child and plan long-term goals |

||

| Week 8 | Telephone session (20 min): review tasks | No contact with therapist |

Overall improvement in child anxiety was assessed using the Clinical Global Impression - Improvement scale (CGI-I), Reference Guy29 a 7-point scale from 1 = very much improved to 7 = very much worse. Scores of 1 and 2 indicate ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improvement and are widely considered to represent treatment success. Reference Walkup, Albano, Piacentini, Birmaher, Compton and Sherrill24 Interrater reliability was established for the CGI-I using the same procedures as for the ADIS. Overall mean interrater reliability for the assessment team was excellent (ICC = 0.96).

Measures of change in child anxiety symptoms and impact

Anxiety symptoms were measured by parent and child self-report using the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS). Reference Spence30 The SCAS consists of 38 items that are rated on 4-point scales to indicate the degree to which the symptoms of anxiety apply to the child (never, sometimes, often and always).

The extent to which anxiety interferes in a child's life was assessed using the Child Anxiety Impact Scale - parent report (CAIS-P), Reference Langley, Bergman, McCracken and Piacentini31 which covers three psychosocial domains (school, social activities and family functioning). The CAIS-P consists of 34 items, each of which is rated on a 4-point scale to indicate how much anxiety has caused problems (not at all, just a little, pretty much, very much).

Measures of change in comorbid symptoms.

Symptoms of childhood depression and behaviour problems were assessed by means of parent and child self-report, using the Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ-C/P) Reference Angold, Costello and Messer32 and the conduct problems subscale from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-C/P). Reference Goodman33 The SMFQ consists of 11 core depressive symptom items that are rated on 3-point scales to indicate whether or not the symptoms apply to the child (true, sometimes true, not true). The conduct problems subscale from the SDQ consists of 5 items rated on 3-point scales to indicate whether or not the behaviour described applies to the child (certainly true, sometimes true, not true).

Statistical analysis

Power and sample size

The study was powered based on the requirement to provide 85% power at the 5% (two-sided) significance level to detect a 28% difference in the proportion of children who recovered from their primary anxiety disorder in both the full and brief guided parent-delivered CBT groups when compared with the wait-list at the post-treatment assessment (primary outcome). Calculations were based on an estimated remission rate for the wait-list condition of 28% (based on this being a group with a relatively favourable prognosis) and on findings that guided self-help CBT may be as effective as a standard therapist-led therapy Reference Rapee, Abbott and Lyneham18,Reference Goodman33 which, for childhood anxiety disorders, has achieved average success rates of 56%. Reference James, Soler and Wetherall10

The sample size required was 52 children per group, which was increased to allow for an estimated 20% loss to follow-up. Thus, it was planned to enrol 195 children into the trial.

Analysis

A statistical analysis plan detailing all pre-specified analyses was prepared and signed off prior to any analysis being conducted. All analyses were conducted according to this plan.

Differences in the primary end-points (recovery from primary diagnosis and overall improvement in anxiety (CGI-I ratings) at post treatment and other binary end-points were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis using a log-binomial regression model adjusting for the minimisation factors (i.e. gender, age, ADIS primary diagnosis, and CSR score).

Change in anxiety symptoms and impact (change in SCAS-C/P and CAIS-P total scores) and change in comorbid symptoms (change in SMFQ and SDQ conduct subscale total scores) at post-treatment and 6-month assessment were analysed using linear regression models adjusting for minimisation criteria and baseline scores.

Sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the impact of missing data included: (i) no adjustment for minimisation criteria; (ii) per-protocol population (those participants who had received at least half of the treatment sessions and had data for the post-treatment assessments); and (iii) multiple imputation analysis. All results from sensitivity analyses were very similar to the main results.

Data from questionnaires at 6 months were limited to those in the treatment arms of the study and were used to assess maintenance of improvement within each treatment group.

It was not possible to adjust for therapist experience in the main analysis as the wait-list children did not receive treatment; however, child outcomes in the treatment arms of the study were explored in relation to therapist experience.

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2, with Stata v12.1 used for multiple imputations (all run on Windows).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were well-balanced across treatment groups (Table 2).

Improvement in anxiety status post-treatment

Change in diagnostic status

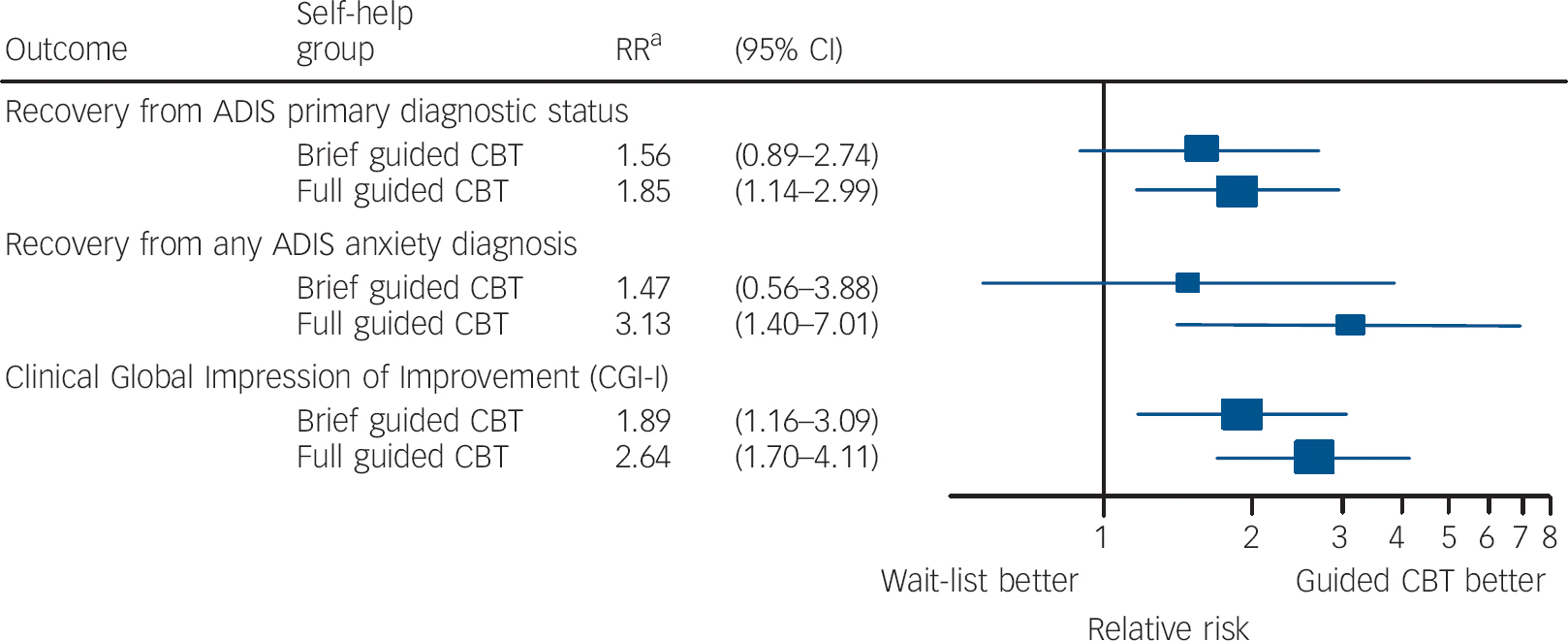

Recovery from primary diagnosis. At the post-treatment assessment children in the full guided CBT group had fared better in terms of recovery from their primary diagnosis than those in the wait-list group. After adjusting for baseline minimisation factors, children in the treatment condition were 85% more likely to have recovered from their initial primary diagnosis than children on the wait-list (relative risk (RR) 1.85, 95% CI 1.14-2.99, P = 0.013). Of those in the full guided CBT group, 25 (50%) had recovered from their primary diagnosis at post-treatment, compared with 16 (25%) in the wait-list group. The effect of brief guided CBT was smaller (Fig. 2), with 18 (39%) of participants recovering from their primary diagnosis post-treatment (RR = 1.56, 95% CI 0.89-2.74, P = 0.119).

Presence of any anxiety diagnosis. At the post-treatment assessment, children who had received full guided CBT were three times more likely to have recovered from all ADIS anxiety diagnoses than those in the wait-list (RR = 3.13, 95% CI 1.40-7.01, P = 0.006). In the full guided CBT condition, 17 participants (34%) had recovered from all anxiety diagnoses, compared with 7 participants (11%) in the wait-list condition. The effect of brief guided CBT was smaller (Fig. 2), with only 7 participants (15 %) recovering from all ADIS anxiety diagnoses (RR = 1.47, 95% CI 0.56-3.88, P = 0.433).

CGI-I post-treatment. At the post-treatment assessment children who had received full guided CBT were 2.6 times more likely to be rated as ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improved than those on the wait-list (RR = 2.64, 95% CI 1.70-4.11, P<0.0001). Of those in the full guided CBT condition, 38 (76%) were rated as ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improved, compared with 16 (25%) in the wait-list condition. Again, the therapeutic impact of brief guided CBT was somewhat smaller, although it was significantly superior to the wait-list group (Fig. 2): 25 participants (54%) in the brief guided CBT condition were much or very much improved post-treatment (RR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.16-3.09, P = 0.011).

Table 2 Baseline characteristics

| Full CBT (n = 64) |

Brief CBT (n = 61) |

Wait-list (n = 69) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 34 (53.1) | 31 (50.8) | 35 (50.7) |

| Female | 30 (46.9) | 30 (49.2) | 34 (49.3) |

| Ethnicity, White: n (%) | 55 (86) | 53 (87) | 58 (84) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Not recorded | 3 (4.7) | 2 (3.3) | 3 (4.3) |

| Single, never married | 5 (7.8) | 4 (6.6) | 3 (4.3) |

| Married (first time) | 30 (46.9) | 41 (67.2) | 41 (59.4) |

| Remarried | 10 (15.6) | 4 (6.6) | 8 (11.6) |

| Divorce/separated | 11 (17.2) | 5 (8.2) | 6 (8.7) |

| Living with partner | 4 (6.3) | 3 (4.9) | 8 (11.6) |

| Widowed | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.3) | |

| Education (primary carer), n (%) | |||

| Not recorded | 6 (9.4) | 3 (4.9) | 5 (7.2) |

| School completion | 13 (20.3) | 15 (24.6) | 11 (15.9) |

| Further education | 26 (40.6) | 27 (44.3) | 33 (47.8) |

| Higher education | 11 (17.2) | 11 (18.0) | 13 (18.8) |

| Postgraduate qualification | 8 (12.5) | 5 (8.2) | 7 (10.1) |

| Overall SES, n (%) | |||

| Not recorded | 6 (9.4) | 3 (4.9) | 6 (8.7) |

| Higher professional | 37 (57.8) | 39 (63.9) | 43 (62.3) |

| Other employed | 17 (26.6) | 14 (23.0) | 18 (26.1) |

| Unemployed | 4 (6.3) | 5 (8.2) | 2 (2.9) |

| ADIS primary diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 16 (25.0) | 14 (23.0) | 15 (21.7) |

| Social phobia | 13 (20.3) | 11 (18.0) | 17 (24.6) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 16 (25.0) | 16 (26.2) | 15 (21.7) |

| Other anxiety disorders | 19 (29.7) | 20 (32.8) | 22 (31.9) |

| ADIS severity of primary diagnosis, moderate (CSR 4) | 9 (14.1) | 8 (13.1) | 5 (7.2) |

| Diagnosis (CSR rating), n (%) | |||

| Moderate (CSR 5) | 19 (29.7) | 16 (26.2) | 22 (31.9) |

| Severe (CSR 6) | 30 (46.9) | 31 (50.8) | 32 (46.4) |

| Severe (CSR 7) | 6 (9.4) | 4 (6.6) | 9 (13.0) |

| Very severe (CSR 8) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Presence of other psychiatric disorders, n (%) | |||

| Dysthymia | 3 (4.7) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (5.8) |

| Major depressive disorder | 2 (3.1) | 5 (8.2) | 7 (10.1) |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 5 (7.8) | 7 (11.5) | 8 (11.5) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 9 (14.1) | 9 (14.8) | 11 (15.9) |

ADIS, Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV; CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy; CSR, clinical severity rating; SES, socioeconomic status.

Maintenance of improvement at 6 months

Primary ADIS diagnostic status at 6 months

At the 6-month post-treatment assessment, 37 participants (76%) who had received full guided CBT and 27 participants (71%) who had received the brief guided CBT no longer met diagnostic criteria for their primary anxiety disorder. Only one of those who had recovered from their primary ADIS diagnosis post-treatment failed to sustain that improvement at 6 months. For the 23 children assessed at 6 months who had not recovered immediately post-treatment, more than half showed improvement: 14 (61%) in the full guided CBT group and 10 (45%) in the brief guided CBT group had improved by 6 months.

Fig. 2 Main trial outcomes at post-treatment assessment.

ADIS, Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy; RR, relative risk. a. Adjusted for gender, age, ADIS primary diagnosis and ADIS clinician severity rating.

Any ADIS anxiety diagnosis at 6 months

Of those who had received full guided CBT, 26 (53%) no longer met criteria for any anxiety disorder diagnosis at 6 months, as did 21 (55%) of those in the brief guided CBT group. All of those who no longer met criteria for any anxiety disorder diagnosis post-treatment sustained their improvement at the 6-month follow-up. Of those who continued to have an anxiety disorder diagnosis post-treatment, 10 (32%) in the full guided CBT group and 13 (43%) in the brief guided CBT group did not meet criteria for any anxiety disorder diagnoses at 6 months.

CGI-I at 6 months

Of those who had received full guided CBT, 37 (76%) were rated as ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improved according to CGI-I criteria at the 6-month follow-up, as were 30 participants (79%) in the brief guided CBT condition. The great majority of those who had shown this level of improvement post-treatment sustained that improvement at 6 months: 31 individuals (84%) in the full guided CBT group and 20 (95%) in the brief guided CBT group. Of those who had not shown ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improvement post-treatment, over half had shown this level of improvement by 6 months: 6 (60%) in the full guided CBT group and 8 (53%) in the brief guided CBT group.

Change in anxiety symptoms, impact and comorbid symptoms (baseline to post-treatment)

There were no differences between either full or brief guided parent-delivered CBT and the wait-list group on any child self-report questionnaire measure of anxiety or comorbid symptoms of low mood or behavioural problems (all P-values >0.37); and nor did the groups differ in terms of parent-reported anxiety symptoms (SCAS-P). On the basis of parent report post-treatment, compared with the wait-list group, for those who had received full guided CBT, there was a significantly greater reduction in the impact of anxiety (CAIS-P difference in change from baseline −5.56 (95% CI −9.40 to −1.73), P = 0.0045) and symptoms of low mood (SMFQ difference in change from baseline −1.44 (95% CI −2.82 to −0.07), P = 0.0395). No significant differences were observed between the brief guided CBT group in comparison to the wait-list group on any parent- or child-report questionnaire measures. A summary of means and distributions is provided in Table 3, together with information on change at the 6-month follow-up in the two treatment groups on questionnaire measures of anxiety and comorbid symptoms.

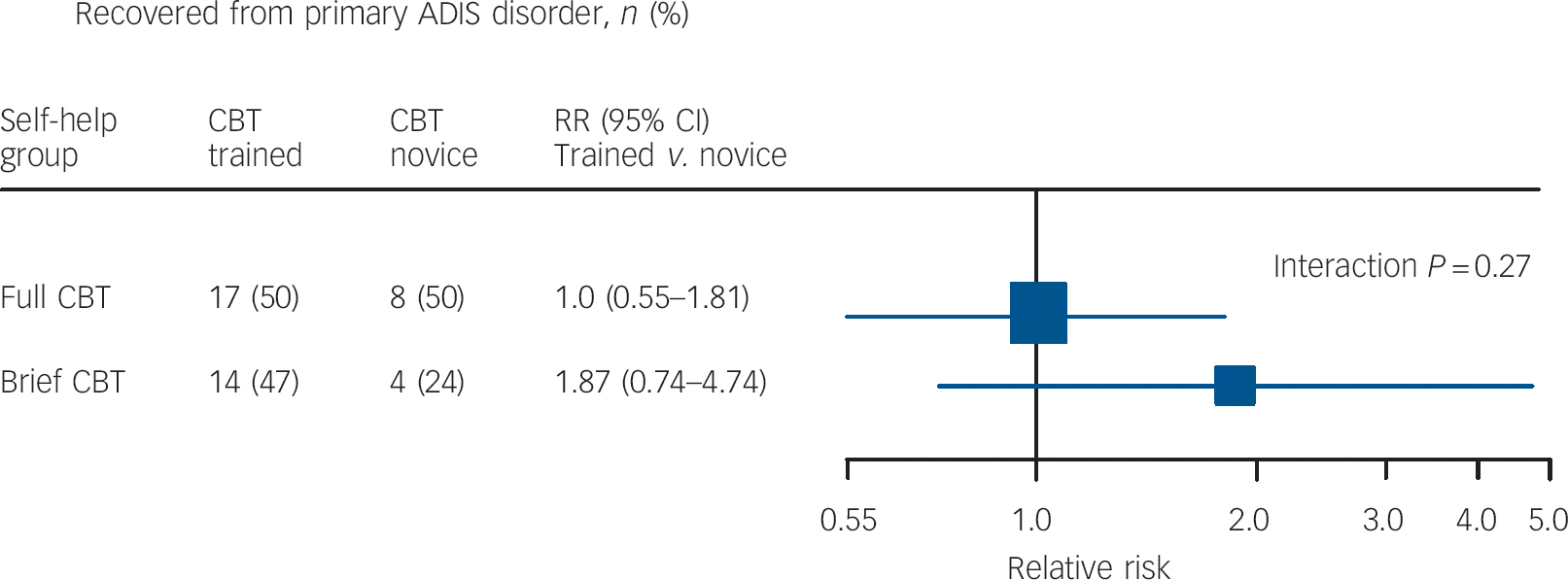

Therapist effects

The proportion of families who were treated by a therapist with some clinical experience and the proportion treated by a novice was balanced across the two treatment arms: 42 participants (66%) in the full guided CBT group were treated by a therapist with some experience, as were 43 (71%) in the brief guided CBT group. The same proportion of children had recovered from their primary diagnosis post-treatment whether they received full guided CBT delivered by an experienced or a novice therapist (trained v. novice RR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.55-1.81). For those who had received brief guided CBT, a somewhat larger proportion (i.e. n = 14 (47%)) of those treated by an experienced therapist recovered from their primary diagnosis compared with the proportion who were treated by a novice therapist (n = 4 (25%)), although the difference was not statistically significant (RR = 1.87, 95% CI 0.74-4.74). The level of therapist training was not differentially associated with outcomes in the two treatment groups (interaction P = 0.27; Fig. 3). The findings with respect to therapist experience were similar for CGI-I post-treatment.

Discussion

Main findings

The current study assessed the efficacy of a guided parent-delivered CBT treatment for child anxiety disorders, where the primary carer did not meet criteria for a current anxiety disorder. Two variations of the treatment were examined: a full version, involving eight weekly therapy sessions, and a brief version, involving four sessions over a similar time period. For both treatments, half the treatment sessions were conducted face to face, and half were 20-minute reviews conducted on the telephone. A further variable of interest was therapists' level of experience and training. Here, child outcome was examined in relation to whether the therapist had some previous clinical experience or whether they had no previous therapeutic experience.

The full guided parent-delivered CBT was found to be an effective treatment for child anxiety. Thus, compared with the spontaneous remission rate among those in the wait-list condition, twice as many of those who had received the full guided CBT recovered from their primary anxiety disorder, and three times as many recovered from all anxiety disorder diagnoses. Notably, the rate of recovery, for both the primary diagnosis and all diagnoses, is comparable to rates reported in previous studies achieved with a full course of individual CBT, commonly involving around 16 1-hour treatment session over 4 months. Reference James, Soler and Wetherall10,Reference Cartwright-Hatton, Roberts, Chitsabesan, Fothergill and Harrington11 In terms of the CGI-I, made by an independent assessor masked to treatment group, three-quarters of those who had received the full guided parent-delivered CBT were rated as at least ‘much improved’, three times the rate among those in the wait-list condition. Outcomes for those who received the brief version of the guided parent-delivered CBT were less impressive. There was no difference in the rate at which children recovered from their primary diagnosis after brief guided CBT compared with those on the wait-list, and a very similar proportion in the two groups recovered from all anxiety diagnoses. However, in terms of CGI-I, compared with the wait-list group, approximately twice as many of those who had received the brief guided CBT were rated as at least ‘much improved’. Results from the questionnaire measures were mixed. Although parents reported greater reductions in the negative impact of their child's anxiety for those who had received the full guided CBT compared with those in the wait-list condition, there were no differences in change in anxiety symptoms based on parent or child report. The questionnaire data need to be interpreted with some caution, however, given the large amount of missing data on these particular measures.

Table 3 Anxiety symptoms, impact and comorbid symptoms at baseline, post-treatment and 6-month follow-up

| Questionnaire | n | Total score at baseline, mean (s.d.) |

n | Total score at 12 weeks, mean (s.d.) |

n | Total score at 6 months, mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spence Children's Anxiety Scale | ||||||

| Child report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 57 | 39.70 (17.54) | 40 | 30.00 (12.6) | 32 | 19.50 (13.86) |

| Full CBT | 60 | 35.47 (16.6) | 47 | 28.47 (20) | 37 | 24.84 (17.19) |

| Wait-list | 66 | 39.83 (19.83) | 57 | 29.40 (16.28) | - | |

| Parent report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 56 | 40.21 (17.44) | 38 | 24.16 (12.93) | 32 | 20.66 (13.59) |

| Full CBT | 59 | 35.56 (17.09) | 42 | 20.45 (11.52) | 38 | 19.21 (12.57) |

| Wait-list | 63 | 37.81 (15.62) | 46 | 24.15 (11.36) | - | |

| Child Anxiety Impact Scale - parent report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 51 | 14.59 (12.38) | 39 | 13.97 (14.64) | 31 | 9.09 (12.52) |

| Full CBT | 51 | 12.35 (12.67) | 41 | 6.39 (6.29) | 37 | 7.95 (9.18) |

| Wait-list | 60 | 17.03 (13.07) | 48 | 15.56 (12.31) | - | |

| Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire | ||||||

| Child report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 57 | 7.58 (5.19) | 42 | 5.57 (5.06) | 31 | 3.23 (3.66) |

| Full CBT | 60 | 6.33 (5.08) | 48 | 3.94 (5.04) | 38 | 4.24 (5.16) |

| Wait-list | 68 | 7.93 (6.26) | 57 | 4.84 (5.38) | - | |

| Parent report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 55 | 6.76 (5.56) | 39 | 4.54 (5.19) | 32 | 4.38 (7.27) |

| Full CBT | 57 | 5.39 (5.42) | 43 | 2.00 (2.77) | 38 | 3.05 (5.71) |

| Wait-list | 62 | 7.35 (6.66) | 49 | 4.86 (5.28) | - | |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | ||||||

| Child report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 58 | 3.02 (2) | 42 | 2.43 (2.03) | 32 | 1.91 (1.77) |

| Full CBT | 61 | 2.41 (1.53) | 48 | 2.35 (4.11) | 38 | 1.63 (1.89) |

| Wait-list | 68 | 2.69 (1.99) | 58 | 2.21 (1.76) | - | |

| Parent report | ||||||

| Brief CBT | 55 | 2.11 (1.73) | 39 | 1.33 (1.49) | 32 | 1.38 (1.31) |

| Full CBT | 61 | 2.00 (2.01) | 43 | 1.19 (1.44) | 38 | 1.16 (1.67) |

| Wait-list | 65 | 2.03 (1.64) | 49 | 1.63 (1.68) | - |

CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy.

Fig. 3 Therapist effect on recovery from primary Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) diagnosis post-treatment. CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy; RR, relative risk.

At the 6-month follow-up assessments, positive clinical outcomes were maintained and there was evidence of sustained improvement. Thus, although a return of previously received diagnoses was extremely rare (only one case), almost half of those rated as not recovered following treatment in terms of their primary anxiety diagnosis were rated as recovered at the 6-month follow-up. Interestingly, this continued efficacy of the treatment appeared to be particularly strong for the group who had received the brief guided CBT; and at this follow-up the recovery rates for both the primary diagnosis and any anxiety diagnosis were virtually identical for those who received the full and the brief form of the intervention.

Somewhat surprisingly, therapist experience did not have a significant impact on outcomes; however, it must be noted that this may be because the study was not powered to detect this. Indeed, where the full guided CBT was delivered, the outcomes for those who had had an experienced therapist were very similar to the outcomes of those who had had a novice therapist. In contrast, for those who had received brief guided CBT, a somewhat larger proportion of those treated by an experienced therapist recovered from their primary diagnosis compared with the proportion who were treated by a novice therapist, although the interaction between training and treatment condition was not statistically significant. When interpreting these findings it is important to keep in mind that few of those therapists classed as having had some clinical experience had had extensive clinical experience, with some members of this group currently undergoing clinical training. Although treatment adherence was generally good, there were some areas which were less satisfactory, most notably relating to setting both a collaborative agenda and client homework, which may be a reflection of the level of therapist clinical experience.

Strengths and limitations

The study is the first randomised controlled trial to examine the efficacy of guided parent-delivered CBT for childhood anxiety within a UK healthcare setting. The sample was derived from referrals to a primary/secondary care clinic and represented children with a broad range of anxiety disorders with a range of severity. The assessors received extensive training and their reliability was assessed and confirmed. Mental state assessments were carried out by assessors masked to treatment condition using systematic assessment procedures. The therapists also received training and close supervision. Rigorous checks were made on treatment content and treatment fidelity was broadly confirmed. Finally, the fact that the trial therapists varied in the extent of their previous clinical experience made it possible to explore the impact on outcomes from this form of treatment delivery in relation to therapists' previous experience.

The study was powered to compare both of the treatments, the full and the brief forms, with a wait-list control. This necessarily entails certain limitations. Without an active treatment control group, it is not possible to say with any confidence how guided parent-delivered CBT for child anxiety would compare with other approaches to the treatment of these disorders. It is interesting to note that the recovery rates compare well with previous reports of outcomes from intensive individual CBT programmes, but this is not strictly evidential. Furthermore, the study excluded children whose primary carer had a current anxiety disorder. It is also the case that no comparison could be made between the full and the brief version of the guided CBT as a much larger sample would have been required for this. The data also suggest that the experienced therapists achieved more or less the same outcomes using the brief form as they did with the full form; however, the study was not powered to address this issue and, again, this can be no more than suggestive. The comparatively large loss of questionnaire data post-treatment and at follow-up was unfortunate and limits the conclusions that can be drawn from these data.

Implications

The findings from this study support a limited body of previous research that has shown significant clinical gains using guided self-help CBT, delivered via parents, for child anxiety disorders. Reference Rapee, Abbott and Lyneham18-Reference Lyneham and Rapee20 This form of treatment has major cost advantages over the standard CBT treatments which commonly involve several weeks of individual face-to-face contact with a specialist therapist. More specifically, the study has shown significant benefit of a parent-led guided CBT for 7- to 12-year-old children with anxiety disorders, whose primary carers do not have a current anxiety disorder. This intervention involved less than 5.5 h of therapist time with just four face-to-face sessions. Furthermore, the treatment was conducted entirely with parents, thereby minimising the disruption to normal child activities (e.g. going to school, after school clubs, being with friends). Another potential benefit of working through parents is that parents are in a strong position to recall and implement strategies learned in treatment on an ongoing basis and, as such, children may be likely to continue to make gains after therapist involvement has ceased. The lack of a comparison group at this later assessment point for our study, however, precludes firm conclusions. Finally, the fact that equivalent clinical outcomes were achieved by novice and experienced therapists suggests that this form of intervention, with appropriate training and supervision, could be widely delivered within the primary care setting. This suggestion needs to be addressed in an effectiveness study.

With the limitations noted above in mind, this study has provided evidence to support the efficacy of a guided parent-delivered CBT treatment for children with a relatively good prognosis and, thus, may be suitable for low-intensity treatments within a UK primary/secondary care setting. To date there has been limited evaluation of low-intensity treatments within children and young people's mental health settings, so these findings are especially timely given the recent introduction in the UK of the Improved Access to Psychological Treatments (IAPT) programme to children and young people.

Funding

The study was supported by the Medical Research Council; K.T. was funded by an MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship, and C.C. was funded by an MRC Clinician Scientist Fellowship.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who took part in the study. We are also grateful to the general practices and Berkshire CAMHS who referred patients to our study, to the therapists who provided treatment, and to the administrators, assessment team and coders at the BCAC.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.