Everyone wants to be happy.

Let’s begin with a thought experiment. Suppose you were not you, but someone not yet existing. Where would you want to be born? Would it be where people were richest, or healthiest or best educated, however happy or miserable they were. Or would you simply ask yourself, ‘Where are people most enjoying their lives, most satisfied and most fulfilled?’ If that was your approach, you would be part of a great tradition of thinkers (going back to the ancient Greeks and beyond) who believed that the best society is the one where people have the highest wellbeing.

By wellbeing we mean how you feel about your life, how satisfied you are. We do not mean the external circumstances that affect your wellbeing. We mean the thing that ultimately matters: your inner subjective state – the quality of your life as you experience it, how happy you are. We shall call this ‘wellbeing’ for short, but we always mean ‘subjective wellbeing’.

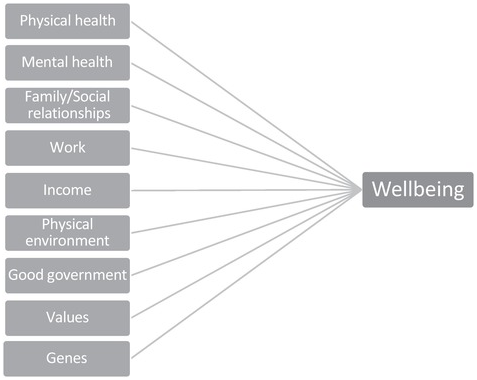

Wellbeing, this book argues, is the overarching good and other goods (like health, family and friends, income and so on) are good because of how they contribute to our wellbeing. This idea is basic to the subject. It is illustrated in Figure I.1, which shows some of the more obvious causes of wellbeing.

So the key to a happier society is to understand how these various factors affect our wellbeing and how they can be altered for the better. Fortunately we have a whole new science to help us do that – the science of wellbeing.

Figure I.1 Some key causes of individual wellbeing

For many people, the motivation for this science is the simple idea that the overarching goal for a society should be the wellbeing of the people. This philosophical idea is not new. In the eighteenth-century Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment, the central concept was that we judge a society by the happiness of the people. But, unfortunately, there was at the time no method of measuring wellbeing. So income became the measure of a successful society, and GDP per head became the goal. But things are different now. We are now able to measure wellbeing, and policy-makers around the world are turning towards measures of success that go ‘beyond GDP’. This shift is really important because, as we shall see, income explains only a small fraction of the variance of wellbeing in any country.

The movement to go beyond GDP brings together two main strands of thought. First, there are those who for over 50 years have argued for wider indicators of progress – the ‘social indicators movement’. This has involved a range of social scientists including some economists like Amartya Sen. Then, second, are those who fear for the sustainability of the planet and for the lives of future generations. For all these groups, it has become natural to support the idea that the overall goal must be the wellbeing of present and future generations.

Fortunately, we can now see more clearly than ever before what is needed to increase our wellbeing. For over the last 40 years a whole new science has developed backed by major new sources of data.

Measurement

The simplest way to measure wellbeing is to ask people ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your life these days?’. Typically, people are asked to respond on a scale of 0 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). People’s answers to this simple question about life satisfaction tell us a lot about their inner state. We know this because their answers are correlated with relevant brain measurements and with the judgements of their friends. They are also good predictors of longevity, productivity and educational performance (another reason for taking wellbeing seriously). And their answers predict voting behaviour better than the economy does – which is a good reason why policy-makers should take wellbeing very seriously!

There are two other ways to measure wellbeing. The first is usually called ‘hedonic’ and involves measuring a person’s mood at frequent intervals. The second is called ‘eudaemonic’. We shall describe both measures in Chapter 1 and explain why we think life satisfaction is the most helpful – how we feel about our life.

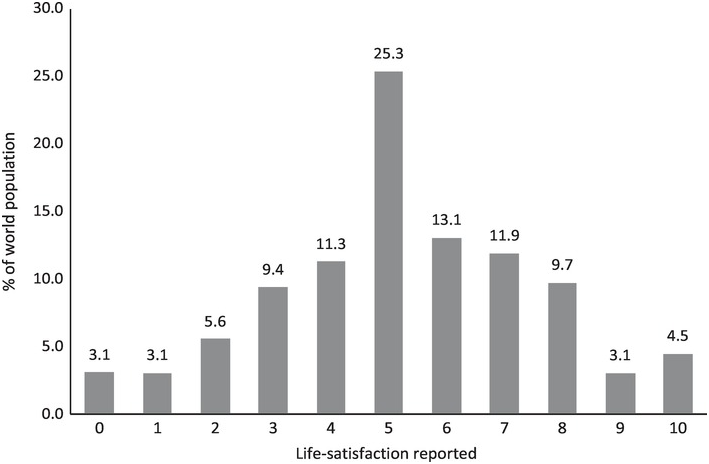

If we focus on life satisfaction, there is a huge inequality of wellbeing in the world. A sixth of the people in the world report wellbeing of 8 or above (out of 10), while at the other end over a sixth report 3 or below (see Figure I.2). This is a huge difference, and, from the wellbeing perspective, this is the most important form of inequality that there is in the world. It is quite possibly the most important fact about the human situation.

Figure I.2 Percentage of people in the world at each level of life satisfaction

So what does determine our life satisfaction? All human beings have similar deep needs – for food and shelter, safety, love and support, respect and pride, mastery and autonomy. How far these are satisfied depends on a mixture of what we ourselves do and what happens to us – a mixture of us as ‘agents’ and of our ‘environment’. This determines the structure of the book.

So in this introduction we shall first describe the structure of the book. And then, to whet your appetite, we shall set out some of the findings in summary form. But don’t worry if they are a bit condensed – all will become clear, chapter by chapter.

This Book

The book begins with two general chapters (Chapters 1–2) on fundamental concepts.

Then Chapters 3–5 describe what we contribute to our wellbeing as ‘agents’ through

o our behaviour,

o our thoughts and

o our genes and our physiology.

Next, Chapters 6–17 describe how we are affected by our environment – what happens to us:

o our family, our schooling and our experience of social media

o our health and healthcare services

o having work

o the quality of our work

o our incomes

o our communities

o our physical environment and the climate of the planet

o and our system of government.

Finally, Chapter 18 shows how policy-makers can use this knowledge to choose policies that create the greatest wellbeing for the people.

Our Behaviour

But why do we need policy-makers and governments at all? In the traditional economic model, people do whatever is best for their own wellbeing, and the process of voluntary exchange leads to the greatest possible wellbeing all round (subject to some qualifications – see below). On this basis, laissez-faire will solve most problems. But modern behavioural science challenges this view of the world, and a founder of behavioural science, Daniel Kahneman, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his challenging work.

There are two main problems. First, people are not that good at pursuing their own best interests. Many people overeat or take little exercise. Some become addicts. Others make changes that they think will improve their lives, without realising that they will soon get used to the new situation and feel no better than before (the process of ‘adaptation’). Moreover, people are hugely affected by how choices are presented to them (like the choice over saving for a pension) – so their preferences are often not well-defined. And in the short term, people are loss-averse – which can lead to greater losses in the long term.

The second key issue is that everybody is hugely affected by how other people behave (in ways other than through voluntary exchange). This is a case of what economists call ‘externality’ – things that happen to you that do not arise from voluntary exchange. Economists have always been explicit that ‘externality’ calls for government action, but they have not always realised how pervasive externality is in human life:

It really matters to us what the pool of other people we live amongst is like – are they trustworthy; are they unselfish?

Other people (society at large) influence our tastes, for good or ill.

If other people or colleagues get higher pay, this reduces the wellbeing we get from a given income.

For all these reasons, there is a major role for governments and for educators in affecting the context in which we live and thus our wellbeing.

Our Thoughts

But there is also a huge role for us as individuals: in determining how our experience of life affects our own feelings. It matters how we think. For our thoughts affect our feelings. The reverse is also true of course – our feelings affect our thoughts. But the way to break into this cycle is by managing our thoughts. The importance of ‘mind-training’ was stressed in many ancient forms of wisdom (such as Buddhism, Stoicism and many religious traditions). But in the West, its importance has been re-established in the last fifty years and proved by state-of-the-art randomised experiments.

In this story of discovery, the first step was cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) – for people with depression or anxiety disorders (led by Aaron T. Beck). These ideas were then expanded into things we can all do, by positive psychology (led by Martin Seligman). In addition, for many people, mind-training is increasingly learned from Eastern practices like mindfulness and compassion meditation.

Our Bodies and Our Genes

Striking new research shows how these mental states affect the workings of the body. At the same time of course, the reverse applies: physical interventions (like psychiatric drugs or exercise) can also affect our minds.

But who are we? An important part of who we are is determined by our genes. Evidence of their importance comes from two sources. The first are twin studies. These show that identical twins (who have the same genes) are much more similar to each other than non-identical twins are. For example, the correlation in wellbeing between identical twins is double what it is between non-identical twins. Any parent who has produced more than one child can see how children differ, even if they are brought up in exactly the same way. Our genes matter and now we are beginning to be able to track down which specific genes are important for wellbeing.

But our environment (social and physical) is also crucial. Moreover, in most cases a person’s development depends not on two separate processes (genes and environment) but on the joint interactive effect of genes and environment. So it is not possible to identify separately which part of a trait is due to genes and which part to environment. And crucially, problems that arise due to genes are often as treatable as those which arise due to experience.

The Inequality of Wellbeing

So how does our experience affect us? The most general way in which to investigate this is by looking at the wide differences in wellbeing across people and finding what factors best explain them.

Of the huge variance of wellbeing in the world, nearly 80% is within countries. And within a country the main ‘personal factors’ explaining the variance are (in rough order of explanatory power):

mental and physical health,

relationships at home and at work,

relationships in the community,

income and

unemployment.

These factors are also the main ones that are responsible (in the same order) for the prevalence of misery (measured by a low level of life satisfaction). So we need a new concept of deprivation. It cannot be based on poverty alone. It must include everything that stops people from enjoying their lives.

However, our wellbeing also depends on broader features of our society, things that do not vary between people but do vary between societies. We can uncover these factors by comparing wellbeing in different countries. These factors include the social norms of trust, support and generosity and the degree of personal freedom. So, if we look across countries, the main ‘societal factors’ that explain the differences in average wellbeing are (in order of explanatory power):

income per head,

healthy life expectancy,

social support,

personal freedom,

trusting social relations and good government,

generosity and

peace.

These two sets of factors (personal and societal) provide the framework for the second half of the book. We look first at the more personal aspects of life (family, school, health, work, income) and then we move to the more societal aspects (community, environment and government). Here are some key findings.

Families and Schooling

Much of our adult life can be predicted from our childhood, and the best childhood predictor of a happy adult life is not good academic performance but a happy childhood. So what then determines whether a child is happy? Obviously parents matter, but it also makes a huge difference which school you go to and which teacher you are taught by.

At home, a child’s key need is unconditional love from at least one adult – together with firm boundaries. The mental health of parents (especially the mother) is the most important measurable factor affecting the wellbeing of children. Children are also profoundly affected by how their parents get on with each other. Fortunately, there are now good evidence-based methods for helping parents who are in conflict and for reducing the likelihood of conflict in the first place.

Schools also have a major effect on children’s wellbeing – as much as all the measurable characteristics of the children’s parents. So it is crucial that schools have child wellbeing as an explicit, measurable goal. And, as many experiments have shown, the life-skills of children can be significantly improved if these skills are taught by trained teachers using well-tested materials.

Mental and Physical Health

However, at present at least a third of the population will have a diagnosable mental health problem at some time in their life. For severe mental illness, medication is required. But all mental illness should also be treated by the relevant psychological therapy. Modern evidence-based therapies for depression and anxiety disorders have at least 50% recovery rates, and they are quite short and inexpensive. But shockingly, even in the richest countries, under 40% of people with mental health problems receive treatment of any kind (including simply medication on its own). This is true of both adults and children.

By contrast, in rich countries at least, most physical illness is treated. But chronic physical pain continues to be very common, with a quarter of the world’s population reporting a lot of physical pain yesterday. It is an important determinant of life satisfaction.

Though modern medicine cannot always eliminate pain, it has been extraordinarily successful at extending the length of life. A comprehensive measure of social welfare takes this into account: by multiplying average wellbeing by life expectancy. This measure provides an estimate of the average Wellbeing-Years (or WELLBYs) per person born. If we use this as a measure of the human condition, we can see just how much the human condition has improved over the last century and over the last decade.

Unemployment

Another key aspect of the human condition is work. The relationship between work and wellbeing is crucial and complex. One of the most robust findings to emerge from wellbeing science is the profound cost of unemployment. Workers who lose their jobs suffer declines in life satisfaction comparable with the death of a spouse. In some cases, those affected fail to recover back to baseline levels of happiness years later, even after returning back to work. The wellbeing consequences of unemployment are about much more than lost wages. Work can provide us with a sense of meaning in life, a source of human connection, social status and routine. When we lose a job, we lose much more than a pay check. As a result, for policy-makers interested in promoting and supporting wellbeing, reducing unemployment ought be a top priority (and finding ways to do this without increasing inflation).

The Quality of Work

However, having a job is not all that matters. How we spend our time at work can be just as important. Despite the overall importance of employment for life satisfaction, working turns out to be one of the less enjoyable activities for most people on a day-to-day basis. While pay is certainly important, the extent to which we enjoy our work proves to be even more dependent on a number of other conditions. Bad working relationships (especially with managers) can profoundly undermine wellbeing at work – for the average person, the worst time of day is when you are with your line manager. In addition, being unable to work the hours we want to work or finding little meaning in our jobs are central threats to wellbeing.

For companies and policy-makers, improving the quality of the workday may be important not only as a matter of principle but also a matter of business. Happier workers are more productive and less likely to quit or call in sick, while happier companies have happier customers and earn higher profits. The potential benefits of supporting wellbeing at work are therefore immense. To this end, a number of companies have begun experimenting with flexible work schedules and family-friendly management practices. We’ll walk through the various methods researchers use to implement and assess these initiatives and what they may tell us about the future of work.

Income

This said, a major motivation for work is income. So a central issue is, To what extent does higher income lead to higher wellbeing? In 1974, Richard Easterlin set out what he argued was an important paradox:

(1) When we compare individuals at a point in time, those who are richer are on average happier.

(2) But, in the long term over time, greater national income per head does not produce greater national happiness.

The first statement is certainly true: in rich countries, a person with double the income of another person will be happier by around 0.2 points (out of 10). This is not a large effect but a worthwhile one. Moreover, the gain in wellbeing from an extra dollar is much more for someone who is poor than for someone who is rich – which is the central argument for the redistribution of income.

But the second statement is still a subject of dispute. At a point in time richer countries are certainly happier than poorer countries. But the effect of economic growth over time seems to vary widely between countries. In some countries, there is a clear positive effect. But there are other countries where there has been strong economic growth but wellbeing is no higher now than it was when wellbeing records first began. These latter countries include the United States, West Germany and China.

There is one obvious reason why extra income might do more for an individual (in a given context) than it would do for a whole population (when everyone gets richer at the same time). This reason is that people compare their own incomes with the incomes of other people. There is abundant evidence (including experimental evidence) that people are less satisfied with a given income the higher the income level of other people. This is an important negative externality – when others work harder and earn more, this reduces my wellbeing. Just as with pollution, the standard way to counter this negative external effect is by a corrective tax. So taxes on income or consumption may be less inefficient than most economists believe – they help to discourage a rat-race that reduces everybody’s wellbeing.

Wellbeing research also reveals something important about the business cycle. Wellbeing is cyclical. When income grows in the short run, people become happier and, when it falls, they become less happy. But the negative effect of the slump is double the size of the positive effect of the boom. So business cycles are bad, and policy-makers should aim to keep the economy stable. This would be true even if greater stability somewhat slowed the long-term rate of economic growth.

The broad conclusion on income is this. Increases in absolute income are desirable, especially in poor countries. But we do not need higher long-term economic growth at any cost, since income is just one of many things that contribute to human wellbeing.

Community

As we have seen, the most important personal factors affecting wellbeing are health and human relationships – at home, at work and in the community. Communities provide vital forms of social connection. Some of this comes from voluntary organisations of all kinds, ranging from sports clubs to faith organisations. The evidence shows that countries are happier when more people belong to voluntary organisations. Moreover, these organisations depend mainly on the work of volunteers, and, as research shows, individuals are happier when they do some voluntary work.

Social norms are also crucial. In a well-functioning community, people have a high degree of trust in their fellow-citizens – people are happier in societies where lost wallets are more likely to be returned and where crime rates are low. Such societies also tend to have less inequality of wellbeing, which is also a powerful predictor of high average wellbeing. (It is also a better predictor of average wellbeing than income inequality is.)

Immigration is a challenge to social harmony, but there is no clear evidence it has so far damaged the average wellbeing of existing residents, and there is clear evidence that it has greatly increased the wellbeing of the immigrants.

In every community, some groups are less happy than others. Minority ethnic groups tend to be less happy (though in the United States at least the gap has been falling). Young people tend to be happier than people in middle age and than people at older ages (except in North America and Europe). But both men and women are almost identical in their average happiness in nearly every country.

The Physical Environment and the Climate of the Planet

Ultimately, human life depends on our physical environment. The evidence shows clearly how people’s wellbeing is improved by contact with nature. But the majority of us now live in cities and work at some distance from our home. The evidence suggests that long commutes reduce wellbeing, since the lower house prices that commuters enjoy are not low enough to compensate for the pain of commuting. Similarly, air pollution and aircraft noise reduce wellbeing (and house prices do not adjust enough to compensate).

But our biggest assault on the environment is our impact on the climate. The world’s average temperature is already over 1°C above its pre-industrial level and, if it exceeds the 1.5°C mark, scientists predict major increases in floods, droughts, fires, hurricanes and sea levels.

It will be future generations who bear the brunt of this. But in the wellbeing approach, everybody matters equally, regardless of when or where they live. So if we follow this approach, we have to maximise the total WELLBYs per person born in present and future generations. Because the future is uncertain, future WELLBYs should be discounted slightly relatively to present ones but by no more than 1.5% a year. (By contrast economists typically discount future real income by around 4% a year – which makes the future much less important.)

Climate change matters so much because we care about the wellbeing of future generations. So there is a natural alliance between those who care about wellbeing and those who care about climate change. And there is another reason for this: both groups agree that what matters is not just income but the overall quality of life, both now and in the future.

Government

Much of what determines the variation in wellbeing around the world relates to individual differences – genes, health, employment, family, income etc. Yet the quality of our lives is also shaped by the country in which we live. For better or for worse, governments play crucial roles in determining our life outcomes and opportunities. Understanding the relationship between governance and wellbeing is therefore essential to understanding differences in wellbeing around the world.

This relationship can be assessed at different levels. First, we can consider what types of governments are more or less conducive to wellbeing. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we find that governments that are able to perform certain essential functions well – (1) enforce the rule of law, (2) deliver good services, (3) pass effective regulation and (4) control corruption – are much more likely to have happier citizens. Democracy and wellbeing are similarly linked. Increasing opportunities for democratic participation in decision-making has been shown to improve wellbeing, regardless of the actual decision made. However, this relationship tends to be stronger in richer countries.

Along similar lines, we can consider the link between wellbeing and political ideology. If we analyse political projects on a spectrum from left to right, which set of policies is most likely to improve wellbeing? Given the impressive diversity of political opinions, the story here gets very complicated very quickly. Nevertheless, some consistent findings have begun to emerge from the empirical literature. The results of these endeavours suggest that reducing inequality, expanding social safety nets and limiting economic insecurity in particular are best positioned to promote and support wellbeing.

We can also flip the script and look at the extent to which wellbeing itself is predictive of political outcomes. Happier voters are more likely to support and vote for incumbent parties. Indeed, in some studies, national happiness levels predict the government’s vote share better than leading economic indicators including GDP per capita and unemployment. This observation provides a strong reason for elected politicians and governments to care about the wellbeing of their constituents.

Similarly, dissatisfaction can provoke political protest. Even in the midst of increasing economic opportunities, declining levels of wellbeing in countries like Egypt and Syria have preceded and predicted uprisings and political protests. In some Western countries too – most notably France and the United States – dissatisfied voters are significantly more likely to support populists, to distrust the political system and to devalue democracy than their happier counterparts.

How to Select Good Policies

So, if wellbeing is the overarching goal, it is what should govern the choices of all policy-makers. This is true whether they are finance ministers, local government officers or leaders of NGOs. And they should take into account the effect of policies upon not only wellbeing but also how many years people live to enjoy that wellbeing. So the key measure of success is the total amount of wellbeing that each person born experiences over their lifetime. This means adding up their wellbeing score for each year that they live. We call the resulting score their Wellbeing-Years (or WELLBYs).

So, any budget-holder would be choosing those policy options that give the highest number of WELLBYS (suitably discounted) for each dollar of cost. That would be the proper meaning of the best ‘bang for the buck’. Benefits would be measured in units of wellbeing and not of money. And monetary benefits would be converted into wellbeing benefits, using an estimate of how money affects wellbeing.

But many policy-makers will of course be keener to reduce misery than to increase wellbeing that is already high. For them the search for new policies could focus especially on those aspects of life that now account for the greatest inequality of wellbeing – and therefore account for the greatest amount of misery. That is a good starting point; and then, when we evaluate specific policies, we could use sensitivity analysis to give extra weight to the wellbeing of people who currently have little of it.

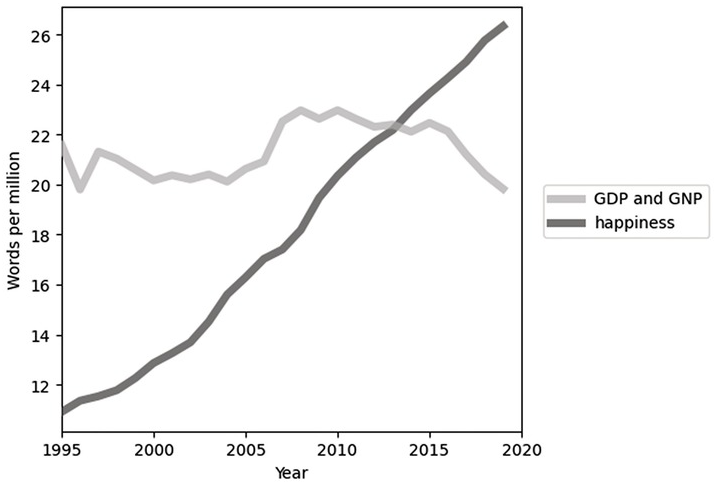

More and more governments are becoming interested in this way of making policy. New Zealand already has an annual Wellbeing Budget, and it is likely that the wellbeing approach will quite quickly become standard practice in many countries. In the meantime, public interest in wellbeing has escalated (see Figure I.3). This has been hugely helped by the annual World Happiness Report, launched annually at the United Nations.

Figure I.3 Recent trends in word frequency in English language books

Note: The darker trace shows the relative frequency of occurrence of the word ‘happiness’ among all English-language books published in each year, as tabulated by Google Books’ n-grams database. The lighter line is the same thing but summed over occurrences of ‘GDP’ and ‘GNP’.

Methodology

In conclusion, wellbeing science is about everything that is most dear to us. But it has to be pursued in a rigorously quantitative way. To explain wellbeing we have to have equations. But to identify what causes wellbeing is not easy. Cross-sectional equations are vulnerable to the problem of omitted variables. Longitudinal panel studies using ‘fixed effects’ help us to deal with this problem. But the most convincing way to establish causal effects is through experiments. In this book, we use all three methods, and (for people not already familiar with these methods) we explain them from the bottom up.

Learning Objectives

So in this book you will learn many things.

First, you will reflect on what is the proper goal for our society and on the idea that the best goal is the wellbeing of the people.

Second, you will learn the state of knowledge about the determinants of wellbeing and the policies that can improve it.

Third, you will become familiar with many different ways of studying causal relationships in social science – and you will also learn to do your own research. For each chapter there are exercises on the book’s website.

Finally, you will see how different disciplines (especially psychology, sociology and economics) can each contribute usefully to understanding how we can produce a happier world.

The science of wellbeing is new and extremely ambitious. It brings together the insights of many disciplines. Its results are as relevant to how we conduct our own lives as to how we want policy-makers to conduct theirs. But there can be no more important way to think about the future of humanity. If we want a happier world, the science of wellbeing is there to help us.