No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

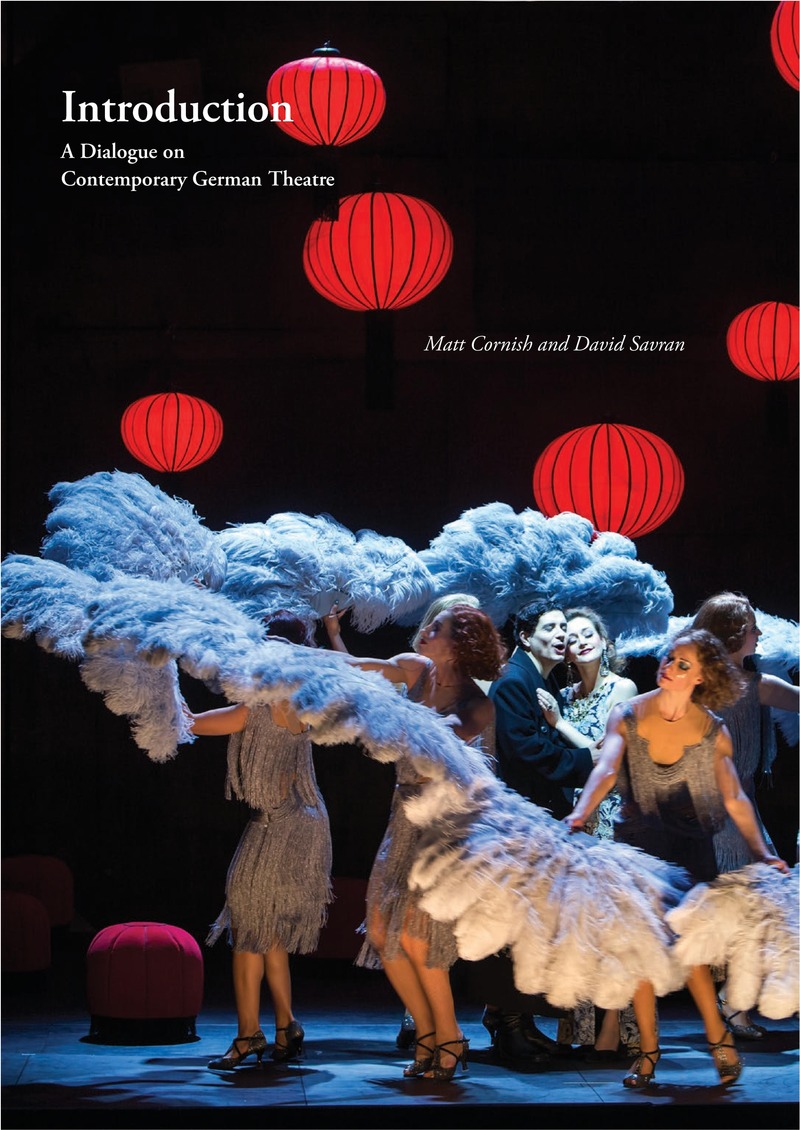

Introduction

A Dialogue on Contemporary German Theatre

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 June 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Special Issue on Contemporary German Theatre

- Information

- Copyright

- © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press for Tisch School of the Arts/NYU

References

References

Adorno, Theodor W. (1970) 2002. Aesthetic Theory. Trans. Hullot-Kentor, Robert. London: Continuum.Google Scholar

Brecht, Bertolt. (1963) 2015. Brecht on Performance: Messingkauf and Modelbooks, ed. Kuhn, Tom, Giles, Steve

, and Silberman, Marc. London: Bloomsbury.Google Scholar

Burke, Kenneth. 1974. The Philosophy of Literary Form. Berkeley: University of California Press.Google Scholar

Dössel, Christine. 2021. “Theater in Zeiten von Immer-noch-Corona: Die Angst schaut mit.” Süddeutsche Zeitung, 13 October. www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/theater-corona-hygienekonzepte-1.5438708

Google Scholar

Emcke, Carolin, and Fritzsche, Lara. 2021. “Wir sind schon da.” Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin 5, 5 February. sz-magazin.sueddeutsche.de/heft/2021/5

Google Scholar

Schiller, Friedrich. (1795) 2007. “Friedrich Schiller: On the Aesthetic Education of Man: Letters 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 14, 15.” Trans. Elizabeth, M. Wilkinson and Willoughby, L.A.. In German Idealism: An Anthology and Guide, ed. O’Connor, Brian and Mohr, Georg, 248–61. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Google Scholar

Theater im Bauturm. 2020. “Quarantänetheater (2020).” Accessed 22 November 2021. www.theaterimbauturm.de/videothek/quarantaenetheater/

Google Scholar

Theatertreffen. 2021. Accessed 6 August 2021. www.berlinerfestspiele.de/en/theatretreffen/start.html. Archived at https://perma.cc/SVQ7-TBB3

Google Scholar

Woolf, Brandon. 2021. Institutional Theatrics: Performing Arts Policy in Post-Wall Berlin. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

TDReading

Hughes, David Ashley. 2007. “Notes on the German Theatre Crisis.” TDR 51, 4 (T196):133–55. doi.org/10.1162/dram.2007.51.4.133

CrossRefGoogle Scholar