Tobacco smoking is a major public health problem and several preventive public health strategies have been implemented. However, smoking remains disproportionately prevalent among people with psychiatric illness Reference Grant, Hasin, Chou, Stinson and Dawson1,Reference Kilian, Becker, Kruger, Schmid and Frasch2 and this is often considered within the mental health profession to be a secondary or deferrable treatment goal to the control of the psychiatric illness. It is becoming increasingly clear that smoking is not innocuous to mental health, and may in fact aggravate mental illness or contribute to its onset. On a neurobiological level, this may be related to the impact of nicotine on monoamine neurotransmitter regulation, including dopamine, via the diffuse cholinergic pathways. Reference Dani and De Biasi3 This may underlie the circadian dysrhythmicity and hedonic dysregulation in smokers, Reference Adan, Prat and Sanchez-Turet4 and may predispose to the development of mood disorders. Smoking also has other systemic and metabolic consequences that may likewise increase this vulnerability.

There is already evidence that smoking is a risk factor for depression. Association data from cross-sectional studies Reference Harlow, Cohen, Otto, Spiegelman and Cramer5,Reference Hamalainen, Kaprio, Isometsa, Heikkinen, Poikolainen, Lindeman and Aro6 support evidence from prospective studies to suggest that smoking pre-dates the onset of depression. Reference Klungsoyr, Nygard, Sorensen and Sandanger7,Reference Steuber and Danner8 However, there is only limited longitudinal data in the existing literature, and most longitudinal studies have involved time frames under 2 years, which may not be adequate to demonstrate the insidious effects of nicotine dependence. In this epidemiological study, we investigated the status of tobacco smoking as a risk factor for major depression using not only cross-sectional data but also longitudinal data that extend over a period of 10 years.

Method

Participants

This study is nested within the Geelong Osteoporosis Study, a programme of research originally designed to investigate the epidemiology of osteoporosis in Australian women, but recently expanded to examine both psychiatric illness and non-psychiatric diseases. The criterion for inclusion into the Geelong Osteoporosis Study is women listed on the current Australian Commonwealth electoral roll for the region known as the Barwon Statistical Division and the criteria for exclusion are inability to provide informed consent, death, and not able to be contacted. Reasons for non-participation are described elsewhere. Reference Henry, Pasco, Nicholson, Seeman and Kotowicz9 During the period 1994–1997, 1494 women recruited into the Geelong Osteoporosis Study have been prospectively followed for a decade. At the time of writing, a further 208 had been recruited during 2005–2007. A total of 1043 women (aged 20–93 years) participated in a psychiatric assessment during the period 2004–2007, thus fulfilling the inclusion criteria for this study. The Barwon Health Research and Ethics Advisory Committee approved the study, and all participants provided informed, written consent.

Data

Lifestyle practices including smoking, alcohol consumption, habitual physical activity levels and exposure to disease were self-reported. Smoking was recognised if individuals reported regularly smoking more than one or two cigarettes per day for at least 6 months, and recorded details of smoking included frequency and period of exposure. Alcohol intake was recognised if alcohol was consumed several times per week or every day. Habitual physical activity was classified as active if participants reported ‘moving, walking and working energetically and participating in vigorous exercise’, otherwise they were classified as sedentary. Cardiovascular disease included hypertension, angina and coronary artery disease; diabetes encompassed both types 1 and 2. Socio-economic status was ascertained using Socio-Economic Index for Areas index scores based on census data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Reference Adhikari10 These data were used to derive an Index of Economic Resources (IER), which was categorised into five groups, according to quintiles of IER for the study region.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV–TR Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID–I/NP) Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams11 was used to identify women with a lifetime history of major depressive disorder and to determine age at onset. Psychiatric interviews were conducted by trained personnel.

Study designs

Case–control

Among 1043 women who underwent psychiatric assessment, 237 were diagnosed with major depressive disorder and 806 had no history of major depressive disorder. Exposure to smoking was recognised if smoking was practised prior to the onset of major depression. Sixty-eight individuals were excluded because their age at major depressive disorder onset was less than 20 years (the minimum age for controls) and four were excluded because it was unclear whether smoking pre- or post-dated major depressive disorder onset. Thus, 165 individuals with major depressive disorder and 806 controls were eligible for analysis in this case–control study.

Retrospective cohort

Among 1043 women who underwent psychiatric assessment, a decade of longitudinal data was available for 835. Based on retrospective data, 164 were excluded because they had experienced a major depressive disorder episode prior to baseline. Among the 671 women aged 20–84 years with no history of major depressive disorder at baseline and who were thus eligible for analysis in this retrospective cohort study, 51 developed de novo major depressive disorder and 620 remained major depressive disorder-free during follow-up. Participants were classified as smokers if they were current smokers at baseline, otherwise they were classified as non-smokers.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 9.0) and Minitab (version 13). Standard descriptive statistics were used to characterise the participants in each study.

In the case–control study, participants were selected as cases (people with major depressive disorder) or controls (people with no major depressive disorder), and exposure to smoking was documented for each group. Logistic regression modelling was performed to determine the association between smoking and major depressive disorder. Age was defined as the age at major depressive disorder onset for cases and age at baseline for controls, and was categorised into age groups for analysis. Smoking was investigated as a binary variable and was also categorised into groups according to the average number of cigarettes smoked per day (0, ⩽10, 11–20, >20 cigarettes/day). Age, socio-economic status, physical illness, physical activity and alcohol consumption were tested in the models as potential confounders and effect modifiers.

In the cohort study, participants with no history of major depressive disorder at baseline were selected, categorised as current smokers or not, and followed until a first major depressive disorder episode or until the end of the follow-up period. The effect of smoking on development of de novo major depressive disorder was examined using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, using age as the time axis. The proportional hazards assumptions were checked using Schoenfeld residuals before and after adjusting for potential confounding by socio-economic status, physical illness, physical activity and alcohol consumption.

Results

Case–control study

Characteristics of the participants involved in the case–control analysis are shown in Table 1. Participants with major depressive disorder were younger and were more often smokers. Exposure to smoking was documented for 73 of the 165 people with major depressive disorder and for 269 of 806 controls. Prevalence of smoking was thus greater among women with major depressive disorder (0.44 (95% CI 0.37–0.52) v. 0.33 (95% CI 0.30–0.37), P=0.008). Exposure to smoking increased the odds for major depressive disorder (odds ratio OR=1.58, 95% CI 1.13–2.23, P=0.008) and this association persisted, albeit attenuated, after adjusting for age (age-adjusted OR=1.46, 95% CI 1.03–2.07, P=0.031). Socio-economic status did not confound the association between smoking and major depressive disorder (age- and socio-economic status-adjusted OR=1.49, 95% CI 1.05–2.11, P=0.026). Similarly, the association was not explained by a history of self-reported cardiovascular disease or diabetes (adjusted OR=1.47, 95% CI 1.04–2.09, P=0.030). Among the 342 smokers, participants with major depressive disorder smoked more heavily than those in the control group (median (interquartile range), 15 (10–20) v. 10 (8–20) cigarettes per day, P=0.059). Compared with non-smokers, the odds for major depressive disorder tended to increase 1.47-fold for women who smoked 11–20 cigarettes per day (P=0.094) and more than doubled for those who smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day (P=0.003) (Table 2).

Table 1 Participant characteristics in the case–control study

| Major depressive disorder (n=165) | No major depressive disorder (n=806) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: median (IQR) | 33 (26–45) | 43 (29–59) | <0.0001 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 73 (44) | 269 (33) | 0.008 |

| Socio-economic status, n (%) | 0.857 | ||

| Quintile 1 (low) | 23 (14) | 125 (16) | |

| Quintile 2 | 33 (20) | 184 (23) | |

| Quintile 3 | 41 (25) | 183 (23) | |

| Quintile 4 | 29 (18) | 142 (18) | |

| Quintile 5 | 39 (24) | 172 (21) | |

| Alcohol users, n (%) | 28 (17) | 144 (18) | 0.784 |

| Physically active, n (%) | 31 (19) | 168 (21) | 0.551 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 56 (34) | 240 (30) | 0.290 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 11 (7) | 48 (6) | 0.727 |

IQR, interquartile range

Table 2 Smoking frequency (number of cigarettes per day) and the risk for major depression a

| Cigarettes per day | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| <10 | 1.02 (0.56–1.88) | 0.88 (0.48–1.64) |

| 11–20 | 1.62 (1.04–2.52) | 1.47 (0.94–2.32) |

| >20 | 2.17 (1.31–3.58) | 2.18 (1.31–3.65) |

a. Non-smokers form the reference group

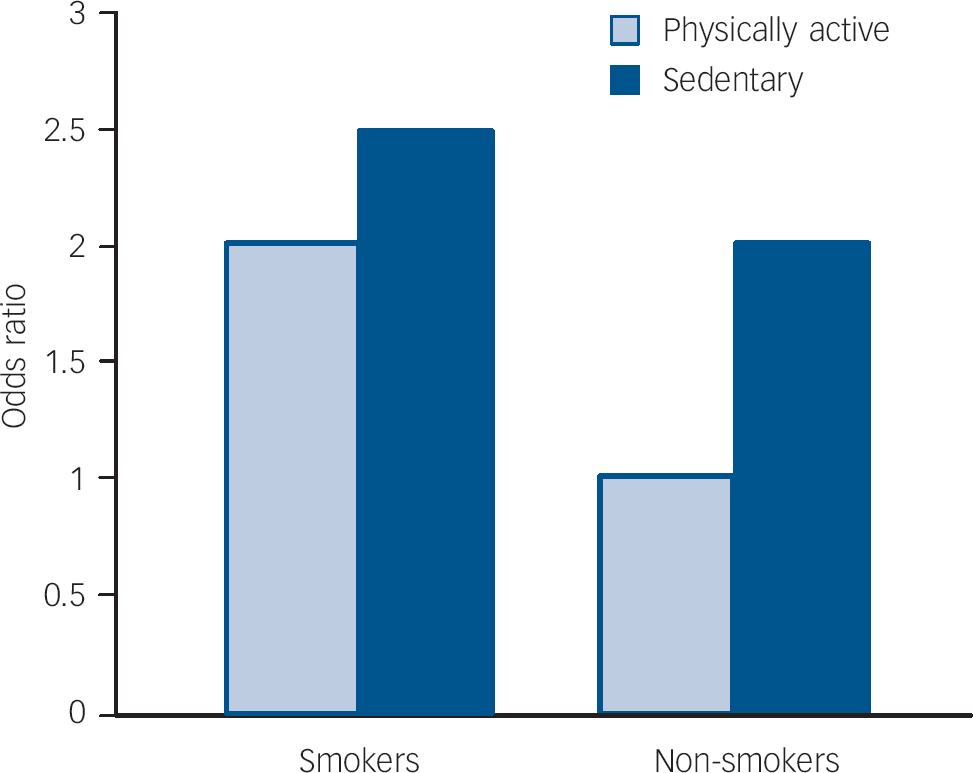

Being physically active was found to be protective against major depressive disorder (age-adjusted OR=0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91, P=0.017). None the less, the association between smoking and major depressive disorder was not explained by differences in physical activity. The independent relationships between smoking and physical activity on the risk for major depressive disorder are shown in Fig. 1. Alcohol consumption did not affect this association.

Fig. 1 Independent contributions of tobacco smoking and physical activity to the risk for major depression. Non-smokers who are physically active form the reference group.

Retrospective cohort study

Characteristics of women included in this analysis are shown in Table 3. Among 87 women who were current smokers at baseline, 13 developed de novo major depressive disorder during 781 person-years of observation, whereas among 584 non-smokers, 38 developed major depressive disorder during 5384 person-years of observation. Estimated rates of major depressive disorder were 16.6 (95% CI 9.7–28.7) per 1000 person-years for smokers and 7.1 (95% CI 5.1–9.7) per 1000 person-years for non-smokers.

Table 3 Participant characteristics in the retrospective cohort study

| Smokers (n=87) | Non-smokers (n=584) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: median (IQR) | 39 (31–52) | 50 (37–63) | <0.0001 |

| Major depressive disorder, n (%) | 13 (15) | 38 (7) | 0.006 |

| Socio-economic status, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Quintile 1 (low) | 26 (30) | 93 (16) | |

| Quintile 2 | 19 (22) | 137 (23) | |

| Quintile 3 | 22 (25) | 107 (18) | |

| Quintile 4 | 6 (7) | 114 (20) | |

| Quintile 5 | 14 (16) | 133 (23) | |

| Alcohol users, n (%) | 20 (23) | 96 (16) | 0.132 |

| Physically active, n (%) | 14 (16) | 69 (12) | 0.258 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 20 (23) | 220 (38) | 0.006 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (3) | 44 (8) | 0.129 |

IQR, interquartile range

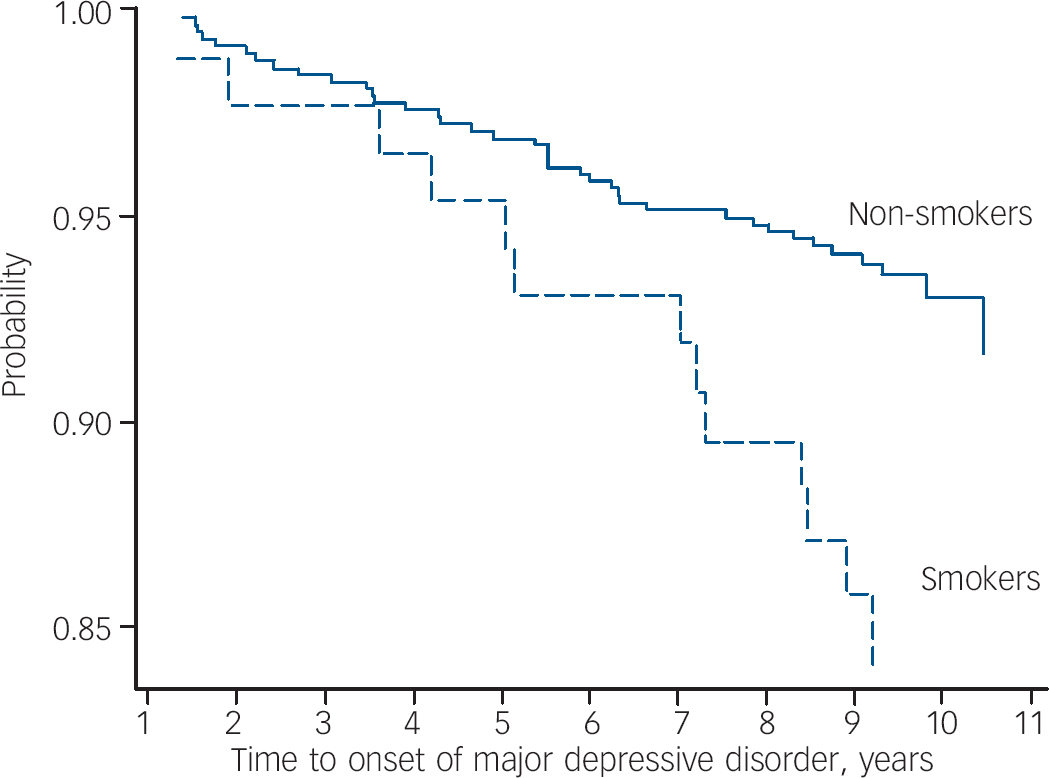

Exposure to smoking was found to increase the risk for developing a first episode of major depressive disorder by 93%, hazard ratio (HR)=1.93 (95% CI 1.02–3.69, P=0.045). A Kaplan–Meier survival plot showing the probability of remaining free of major depressive disorder over a 10-year period for women exposed and unexposed to smoking at baseline is shown in Fig. 2. Adjustment for socio-economic status enhanced the risk (adjusted HR= 2.01, 95% CI 1.03–3.93, P=0.042). Further adjustment for alcohol consumption, physical activity or physical illness did not attenuate this association.

Fig. 2 Survival plot (Kaplan–Meier) showing the probability of remaining free of de novo major depressive disorder over a 10-year period for smokers and non-smokers at baseline.

Discussion

This study provides both cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence consistent with the hypothesis that tobacco smoking is associated with major depression. Our cross-sectional data demonstrate that exposure to smoking is associated with a 1.46-fold increase in the odds for major depressive disorder. Furthermore, our findings are suggestive of a dose-dependent association, with more than a two-fold increase in the odds of major depressive disorder for heavy smokers compared with non-smokers. With the advantage of temporal sequencing, our longitudinal data demonstrate that smoking is associated with a near doubling of risk for developing de novo major depressive disorder over a 10-year period. These effects were independent of age and physical activity, and not explained by alcohol consumption.

Other cross-sectional studies have reported increased odds of depression in smokers, Reference Harlow, Cohen, Otto, Spiegelman and Cramer5,Reference Hamalainen, Kaprio, Isometsa, Heikkinen, Poikolainen, Lindeman and Aro6 with results retaining statistical significance after adjusting for other major risk factors. Reference Hamalainen, Kaprio, Isometsa, Heikkinen, Poikolainen, Lindeman and Aro6 Prospective studies, although limited, have further strengthened the suspected role of smoking in depression. In an 11-year population-based longitudinal Norwegian study, the hazard ratio for a first depressive episode increased with smoking in a dose-dependent fashion, such that the heaviest smokers (exceeding 20 cigarettes per day) had over four times the risk of those who had never smoked. Reference Klungsoyr, Nygard, Sorensen and Sandanger7 Increased incidence of major depression in smokers has been reported in other shorter studies, Reference Breslau, Kilbey and Andreski12,Reference Breslau, Peterson, Schultz, Chilcoat and Andreski13 including data from adolescents. Reference Brown, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Wagner14 Longitudinal studies have also shown a reverse relationship, in which the presence of depression increased the risk of smoking progression. Reference Breslau, Kilbey and Andreski12,Reference Breslau, Peterson, Schultz, Chilcoat and Andreski13 Positive effects on psychomotor performance and enhanced craving, as demonstrated in a physiological study, Reference Malpass and Higgs15 may be pertinent factors for this observation. Other studies have provided support for a third possibility, that depression and smoking coexist as epiphenomena of a common underlying cause, such as genetic factors. Reference Kendler, Neale, MacLean, Heath, Eaves and Kessler16,Reference Korhonen, Broms, Varjonen, Romanov, Koskenvuo, Kinnunen and Kaprio17 The efficacy of bupropion in the treatment of both depression and nicotine dependence Reference Foley, DeSanty and Kast18 may indicate some commonality between the two conditions on a neurochemical level.

Dopamine is one such factor, which is believed to have a dual role in depression and in the mechanism of addiction. Neurochemical studies of depression, particularly with psychomotor retardation, reported an association with diminished dopamine metabolism, as evidenced by decreased levels of cerebrospinal fluid homovanillic acid. Reference Korf and van Praag19,Reference Post, Kotin, Goodwin and Gordon20 Reduced striatal dopamine function has also been shown in dopamine D2 receptor neuroimaging binding studies. Reference Ebert, Feistel, Loew and Pirner21,Reference Martinot, Bragulat, Artiges, Dolle, Hinnen, Jouvent and Martinot22 Dopamine is regarded as the central neurotransmitter of reward, and as having a key role in the reinforcement of the pathways to addiction. Reference Di Chiara and Bassareo23 Dysregulation of the dopaminergic system in addictive states is also a plausible mechanistic pathway to depressive vulnerability. Reference Malhi and Berk24

Smoking-induced oxidative stress is another factor. Tobacco smoke generates free radicals, causing lipid peroxidation, oxidation of proteins and other tissue damage in smokers. Reference Hulea, Olinescu, Nita, Crocnan and Kummerow25,Reference Ozguner, Koyu and Cesur26 Depression has been characterised by elevated markers of oxidative stress Reference Ozcan, Gulec, Ozerol, Polat and Akyol27–Reference Khanzode, Dakhale, Khanzode, Saoji and Palasodkar29 that demonstrates a positive correlation with depressive severity Reference Yanik, Erel and Katoi30 and a return to normal levels after treatment. Reference Bilici, Efe, Koroglu, Uydu, Bekaroglu and Deger28,Reference Khanzode, Dakhale, Khanzode, Saoji and Palasodkar29 It seems plausible that depression could be among the oxidative stress sequelae of smoking.

There are several strengths and potential weaknesses in our study. The length of the follow-up period is a key strength, especially when published longitudinal studies have rarely exceeded a few years at most. Given that smoking effects insidious biochemical changes that are naturally accommodated by the body's homeostatic responses, long-term sequelae such as depression, cancers, cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases may only be reliably demonstrated over an extended time frame. Recall limitations may have affected our ability to accurately diagnose the time of onset of depressive episodes and, in the case–control analysis, the potential exists for differential recall bias of smoking practices. However, as this study was nested within a larger prospective study, the latter risk was minimised as exposure to smoking had been documented prior to psychiatric interview. Furthermore, documentation of exposure to smoking and assessment of outcome were performed by different study personnel. The duration of smoking prior to the onset of depression was unknown, precluding estimation of duration of exposure on depression. Inconsistencies in the number of cigarettes smoked per day may have resulted in misclassification of smoking frequency in the case–control analysis but the apparent dose-dependent association strengthens the notion that smoking is a risk factor for major depression. Small numbers limited a comparable investigation in the longitudinal analysis. Also in the longitudinal analysis, changes in exposure status during follow-up have not been identified. Finally, as in all observational studies, there may be unrecognised confounding. We relied on self-reported history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes as indicators of physical illness that may be affected by smoking status. However, we cannot exclude possible confounding by unrecognised comorbidity as individuals were not clinically screened for all potential physical illnesses. Physical activity and alcohol consumption were explored as concomitant lifestyle factors with a potential for confounding because physical activity had been previously reported as protective against depression, Reference Strawbridge, Deleger, Roberts and Kaplan31 whereas physical inactivity Reference Brown, Ford, Burton, Marshall and Dobson32–Reference Farmer, Locke, Moscicki, Dannenberg, Larson and Radloff34 and alcohol misuse Reference Hamalainen, Kaprio, Isometsa, Heikkinen, Poikolainen, Lindeman and Aro6 are regarded as risk factors. In this study, alcohol consumption did not appear to confound the association between smoking and depression; however, we acknowledge that our criteria for alcohol consumption may have been too broad to confidently exclude its contribution. Other factors predisposing to depression, such as personality traits, developmental and family history of depression, IQ or stress, were not considered as these data were not available.

Within these limitations, however, our data corroborate literature that reveals a malevolent role of smoking in depression and suggest that greater efforts are required in targeting smoking as a routine intervention. Reference Berk35 Depression's status as a leading cause of global disease burden, Reference Murray and Lopez36,Reference Mathers, Vos, Stevenson and Begg37 one that is not anticipated to yield in the coming decades, Reference Murray and Lopez36 can only underscore the potential impact of any effective preventive measures.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Eli Lilly. Postgraduate scholarships were provided by the University of Melbourne, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences and the Australian Rotary Health Research Fund. We thank Sharon Brennan for obtaining the socio-economic data for the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.