In 1854, France created the Bank of Senegal in Saint-Louis, an island at the mouth of the Senegal River. Following the Treaties of Paris of 1814–1815, the country had progressively expanded its political influence over West Africa from its foothold in Saint-Louis, granting French citizenship rights to the inhabitants of Saint-Louis and Gorée Island, and later extending this privilege to inhabitants of Dakar and Rufisque on the Senegalese coast. The exceptional status granted to these four communes led to the establishment of the Bank of Senegal—the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa—which was modeled after the Bank of France.

A number of studies have discussed the formation of monetary and financial systems in French West Africa. Contemporary doctoral theses have described the legal and institutional frameworks of French colonial banks (including the Bank of Senegal) at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Renaud Reference Renaud1899; Denizet Reference Denizet1899; Goumain-Cornille Reference Goumain-Cornille1903; Mingot Reference Mingot1912). Some of the later histories of finance in Francophone Africa also touch upon the Bank of Senegal (Alibert Reference Alibert1983; Dieng Reference Dieng1982; Leduc Reference Leduc1965; BCEAO 2000). Furthermore, Ghislaine Lydon (Reference Lydon, Becker, M’baye, Thioub and du Sénégal1997) and Roger Pasquier (Reference Pasquier1967, Reference Pasquier1987) illustrate how the bank was created in relation to the process of slave emancipation, with a portion of the indemnity titles given to former slave owners becoming shares of the Bank of Senegal. The most influential specific argument has been presented by Amady (or Amadou) Aly Dieng (1932–2015), a former banker at the Banque Centrale des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (BCEAO) and a prominent Senegalese scholar, who was described by Jean Copans and Françoise Blum (Reference Copans and Blum2016) as a radical African nationalist and genuine Marxist. Based on Pasquier (Reference Pasquier1967), Dieng (Reference Dieng1982:39–45) stresses the fact that Europeans who were not principal slave owners as of the French emancipation in 1848 acquired indemnity titles and became major shareholders of the Bank of Senegal. He also argued that a few Bordelais traders, especially Maurel & Prom which held a large number of shares, paralyzed the bank’s development and deliberately sidelined possible competitors who might have benefited from the bank’s services. Following Dieng, Yves Ekoué Amaïzo (Reference Amaïzo2001), who provides detailed information on specific services provided by the Bank of Senegal, concludes that this emerging colonial monetary system marginalized African merchants. Lydon (Reference Lydon, Becker, M’baye, Thioub and du Sénégal1997:485, 489–90) also confirms the poor management of the bank’s operations and the dominance of large French trading houses as shareholders despite the fact that these firms were not frequent users of the bank’s services.

The origin of the company group Maurel & Prom can be tracked back to a tiny firm established by Hubert Prom (1807–1896), who arrived on Gorée Island in 1822. In 1828, he opened a store in Gorée, with a branch in Saint-Louis (Baillet Reference Baillet1923:2). In 1831, the firm was reorganized with the help of Prom’s cousin Hilaire Maurel (1808–1884) and was established as H. Prom et Maurel in Saint-Louis (Péhaut Reference Péhaut2014:Ch.1). Both founders married daughters of Armand Laporte, a métis notable and Gorée’s mayor (De Luze Reference De Luze1965; Baillet Reference Baillet1923; Péhaut Reference Péhaut2014). Their business flourished in both Africa and Bordeaux, and it spawned successor companies such as Maurel et H. Prom, Maurel et Cie, and Maurel et Frères. This article collectively refers to them as Maurel & Prom. Among them, Maurel et H. Prom, which played a central role in this family business, was later taken over and run by Hilaire Maurel’s descendants, who were métis merchants. Therefore, the firm should also be recognized as such, rather than as a mere Bordelais company. Maurel & Prom in general played a significant role in the French colonization of West Africa, including in the appointment of General Faidherbe as governor in 1854 (Barrows Reference Barrows1974).

This article seeks to qualify Dieng’s argument. It argues that the fact that Maurel & Prom accumulated shares from indebted indigenous merchants and thus became the Bank of Senegal’s largest shareholder did not mean that the bank operated under the company’s directives. Unlike the modern system in which voting rights are linked to the number of shares held, the bank’s articles of association allowed each shareholder to have only one vote at shareholders’ meetings.Footnote 1 Thus, minor shareholders could exert an influence on bank management that was equal to that of larger shareholders.

Senegalese society in the nineteenth century was very complex, being composed of Europeans, Africans, and Métis, with some Métis having solid familial ties to Bordeaux merchants, while others had stronger relationships with Africans in the interior. Therefore, distinguishing clearly between Bordelais and métis is not easy. Further, the métis merchants whom Dieng (Reference Dieng1982) identified as French or Bordeaux merchants could be divided into those closely associated with French colonial administrators and others who stood in opposition. Notably, Gaspard Devès, categorized as a “Bordeaux merchant” by Dieng, had strong ties to Africans in inland areas and was often at odds with Maurel & Prom. Moreover, at the end of the nineteenth century, Gaspard Devès and his son Justin II formed a political alliance with Louis Descemet and François Carpot to resist the French invasion of the interior (Manchuelle Reference Manchuelle1984; Jones Reference Jones2012, Reference Jones2013; Ngalamulume Reference Ngalamulume2018; Johnson Reference Johnson1971). In short, métis merchants flexibly changed their alliances depending on a range of issues, including emancipation, gum Arabic trade, local politics, and even French colonial expansion.

Due to its ties to the legacy of the slave system and colonialism, all currencies issued in Senegal since the era of the Bank of Senegal to the present have always been tainted with a negative image. Nevertheless, Senegal developed an advanced economic and financial system ahead of other African countries, even if this meant the imposition of the French system on the colony. While it is undeniable that there were occasional instances of breach of trust by management, the discussions at shareholders’ meetings show that the bank’s administrators were primarily committed to increasing the bank’s profits and attracting creditworthy clients. The elaborate mechanism of bank operations—judging by the standards of the time—suggests that French authorities prioritized the establishment of a stable colonial financial system rather than the privileging of a particular ethnic group. The bank provided credit to indigenous merchants who requested it and facilitated financial transactions between metropolitan France and Senegal. Some of the bank’s administrators maintained associations with African merchants and were critical of both the bank’s largest shareholder, Maurel & Prom, and the French colonial administration.

This article assesses how and in whose interest monetary and financial relationships were formed between metropolitan France and Senegal by analyzing the operations of the Bank of Senegal.Footnote 2 After highlighting the link between slave emancipation and the establishment of the bank, this article will analyze the complex relations between the bank and its shareholders within the context of Franco-Senegalese commercial relations. Subsequently, the discussion will focus on the bank as an agent of colonial monetization and as a provider of financial services. The final section addresses the bank’s performance over nearly half a century of operation and examines its connections to the formation of a French colonial economy. It suggests that, between 1854 and 1901, the Bank of Senegal was, rather than an organization that alienated Africans, a site of political struggles among métis merchants over the control of the Senegalese colony.

Slave Emancipation and the Establishment of a Colonial Bank

In 1844, the colonial administration surveyed slave owners and major Senegalese and European traders on the subject of slave emancipation (Lydon Reference Lydon, Becker, M’baye, Thioub and du Sénégal1997:476). Unlike the situation in the French colonies of the West Indies, Senegal’s slave owners were not Europeans, but rather mostly métis and Africans. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that some of them were opposed to emancipation. According to Lydon, almost all African traitants who conducted business along the Senegal River and signares (mulattoes) were against abolition.Footnote 3

It is telling that the survey also included a question on the establishment of a commercial bank (caisse d’épargne) in Senegal. Most Senegalese, facing extremely high interest rates on credit that they received from merchants in the port towns of metropolitan France, favored the establishment of such a bank (Lydon Reference Lydon, Becker, M’baye, Thioub and du Sénégal1997:476–77; Dieng Reference Dieng1982:38). Furthermore, the trade of gum arabic, for which guinée cloth was used as a credit instrument, tended to destabilize the income of African intermediaries, causing them to incur large debts (Hardy Reference Hardy1921; Bouët-Willaumez Reference Bouët-Willaumez1848; Masaki Reference Masaki2022a, Reference Masaki and Pallaver2022b). The high interest rates offered by European merchants were also a great burden to them. Therefore, local traders needed a financial institution from which they could obtain credit on favorable terms. French merchants, on the other hand, largely opposed the establishment of such a bank, fearing that it would reduce their profits (Lydon Reference Lydon, Becker, M’baye, Thioub and du Sénégal1997:477).

The abolition of slavery affected all French colonies and required the government to provide compensation, not to enslaved people but rather to slave owners. For this purpose, the French government established banks in Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Reunion, and Senegal. The compensation measure arrived on April 30, 1849 (a year after the abolition decree of April 27, 1848) and stipulated the payment of six million francs in cash, as well as the same amount in annuities with a five percent yield, to slave owners. To pay this annuity over twenty years, the French government earmarked 120 million francs in its General Ledger of Public Debt (Grand livre de la dette publique).Footnote 4 The total compensation amounted to 126 million francs for 248,320 slaves.Footnote 5 However, the amounts allocated to each of the five French colonies varied considerably. In Senegal, the government allotted only 105,503.41 francs for cash payments and 2.11 million francs for the creation of a fund that would pay an equivalent amount in annuities. These payments were distributed to the owners of 6,240 slaves and 650 engagés, a category that brought half the compensation for a slave.Footnote 6 In French, the word “engagé” can mean “volunteer,” but according to a local arrêté from September 28, 1823, these were in reality forced laborers. In Senegal, the average compensation per slave was only approximately 330 francs, an amount that was much smaller than the 500 francs originally promised. Furthermore, it was planned that only approximately 15 to 16 francs of the compensation would be paid in cash, with the same amount to be paid in annuities over twenty years. Thus, unsurprisingly, many former slave owners who were already in debt chose to hand over their entitlements as compensation to their creditors. Maurel & Prom became the largest buyer of these entitlements.Footnote 7

The decree of December 21, 1853, formally allowed the creation of the Bank of Senegal with capital in the amount of 230,000 francs. The Bank of Senegal’s capital was modest compared to the three-million-franc capital stock of the colonial banks of Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Reunion. Each colonial bank divided its capital into shares worth 500 francs each. Part of the capital for each of these colonial banks came from one-eighth of the amount that had been set aside for paying annuities. Consequently, those who held compensation entitlements became shareholders of these banks and received dividends instead of annuities. As the name banque de prêt et d’escompte (bank for loans and discounting) indicates, the primary role of these colonial banks was initially to provide credit to the local economy. However, by law, on July 11, 1851, the banks also became responsible for issuing local banknotes.

In this manner, French merchants who did not own slaves became major shareholders of the Bank of Senegal by collecting entitlements as payment from debtors who were former slave owners. Dieng seems to have concluded that the merchants who became major shareholders were able to exclude their rivals from access to credit provided by the Bank of Senegal, but while it is not unusual for major shareholders to intervene in the management of a modern joint stock company, this was not actually the case with the Bank of Senegal.

Who Owned the Bank and How Did Governance Work?

The Bank of Senegal became operational in 1855 as a limited liability company. Although it was owned by shareholders, the bank was under government control. The French president appointed the director of the bank from a pool of three candidates recommended by the supervisory commission of colonial banks ( Commission de surveillance des banques coloniales ) in Paris, in accordance with a July 1851 law which regulated the Ministry of the Navy and Colonies.Footnote 8 The commission supervised the operations of all colonial banks, examined all bank-related documents that reached the ministers, and served as an auditing board for the ministers. Additionally, a newly established Central Agency for Colonial Banks (Agence centrale des banques colonials) facilitated transactions in Paris on behalf of all colonial banks, acting alongside the minister of colonial affairs as the banks’ delegate in the supervisory commission. The French colonial minister chose the head of the Central Agency for Colonial Banks from a set of three candidates who were also nominated by the supervisory commission of colonial banks.

Under the supervision of these public institutions in metropolitan France, managerial decisions for the Bank of Senegal were made by the general meeting of shareholders and the Board of Administrators’ meetings, both of which were held in Saint-Louis. Consequently, shareholders’ meetings were not well attended, since many shareholders lived far from Saint-Louis, and the Board of Administrators, who met on Tuesdays and Fridays each week, made most of the important decisions.

The Board of Administrators was composed of the director and four administrators, including the principal treasurer of the colonial administration. In addition, the bank had two auditors, one of whom was a colonial inspector. Each official was required to hold a fixed number of bank shares: ten shares for the director and five shares each for administrators and auditors. These shares were to remain unpledgeable and inalienable during the officers’ time in office. The bank’s director annually received remunerations amounting to 6,000 francs in 1867, which had increased to 12,500 francs by 1897. However, administrators and auditors could only receive attendance fees. When the bank earned sufficient profits, it paid out 5 percent of its share capital to shareholders and divided the rest into two halves, paying one half to shareholders as complementary dividends and distributing the other between the director (10 percent), the employees (10 percent), and the reserve fund (80 percent). This system must have given directors, shareholders, and employees an incentive to prioritize the bank’s interests.

Details of the Bank of Senegal’s early performance are not available, but it appears that the bank was badly managed and performed poorly until 1867 (Lydon Reference Lydon, Becker, M’baye, Thioub and du Sénégal1997:485–86). The turning point came during M.S. Haurigot’s tenure as director, from 1867 to 1872, a period which saw a rise in the bank’s share price from 375 to 575 francs.Footnote 9 Haurigot also regularized the list of shareholders, which he deemed imprecise.Footnote 10 According to this list, 19 inhabitants of Gorée held 68 shares in total as of May 1, 1869; 20 residents of Saint-Louis held 67 shares, and a single shareholder in Gambia held 12 shares.Footnote 11 By contrast, twelve shareholders who were either French-based companies or residents of France held 303 out of 450 shares.Footnote 12 Maurel & Prom held 135 of the 303 shares, and Haurigot’s list suggests that eight Bordeaux-based merchants held 262 shares (58.2 percent). This figure has often been cited as proof that Bordelais merchants dominated the Bank of Senegal. However, a closer look at the evidence paints a different picture.

Significantly, the bank’s articles of association stipulated that each shareholder be allotted only one vote at the shareholders’ meeting, regardless of the number of shares held. According to the list of all shareholders found in Dieng (Reference Dieng1982:137–38), as of 1869, the total number of shareholders had reached fifty-two, of which fifteen owned only one share, and twenty-three held no more than two shares. Only the fifty top shareholders could attend shareholders’ meetings, and the top three shareholders were involved in establishing the provisional board that appointed the secretary who chaired the meetings.Footnote 13 However, all participants voted equally on issues related to the bank’s management and the selection of new administrators and auditors.Footnote 14 Thus, Maurel & Prom, the largest shareholder, likely had less power to manipulate the bank’s operations than has been previously suggested.

Further, one should not assume that all shareholders categorized as Bordelais merchants always agreed with one another. This category included G. Devès & G. Devès et Co (18 shares) and Devès and G. Chaumet (six shares). As of 1869, Haurigot categorized all companies related to the Devès family as Bordeaux-based.Footnote 15 Of these, the firm of Devès and G. Chaumet was founded in Bordeaux in 1866 by the widow and sons of Justin Devès (Justin I, 1789–1865) after the dissolution of his former firm, Devès, Lacoste & Cie (Bonin Reference Bonin, Favier, Gayot, Klein, Terrier and Woronoff2009:215–16). In contrast, G. Devès refers to Gaspard Devès, who was born in Gorée to Bruno Devès, a brother of Justin I, and Coumbel Ardo Ka, a Fulbé woman. Gaspard spent most of his life in Senegal and played an important role as a businessman and politician in métis society (Jones Reference Jones2013). Hilary Jones (Reference Jones2013:191) classified Gaspard as a member of the Senegalese branch of the Devès family and Justin I as belonging to the Bordeaux branch.

The shareholder list also includes A. Teisseire & Fils (18 shares) as a Bordeaux-based company. However, François Manchuelle has stated that, in the late nineteenth century, the Teisseire company was principally based in Saint-Louis rather than Bordeaux (Reference Manchuelle1984:479). Furthermore, Teisseire was often represented at bank meetings by Louis Descemet, a business partner of the family who began his career as a secretary to the governor, General Faidherbe.Footnote 16 Jones argues that Descemet’s strong ties with Bordeaux-based traders actually lent him prestige in commune politics (Reference Jones2013:155). He served as president of the General Council from 1879 to 1890 and as president of the Chamber of Commerce in Saint-Louis from 1881 to 1889. He also served as Mayor of Saint-Louis (1895–1911), and intermittently as an administrator and auditor for the Bank of Senegal.

Both Gaspard Devès and Louis Descemet had matrilineal kinship relations with African merchants in inland areas. Initially, they were rivals in business and local politics. However, from the 1880s onward, they cooperated to defend local political institutions, such as the office of the mayor (maire) and the general council, which were gradually losing their autonomy. Devès and Descemet were critical of the 1882 creation of a French protectorate, which divided the colony into two parts: the four communes and the territories under “protection” (pays de Protectorat). Unlike the four communes, the protectorate was run by the military and was therefore more subject to French control.

In Senegal, métis merchants often represented small factions with competing interests. However, by the 1890s they also sought alliances as circumstances demanded (Jones Reference Jones2013; Péhaut Reference Péhaut, Bonin, Hodeir and Klein2008). Devès and Descemet began to cooperate in elections, and they succeeded in sending a métis deputy, François Carpot, to represent the colony of Senegal in the French Parliament in 1902. Carpot called himself a “child of the land” (enfant du pays), challenging the control of Bordeaux-based merchants over Senegalese politics and promising to defend the rights of local people and “fight for” Senegal’s place in the new federation of French West Africa (AOF) (Jones Reference Jones2013:169). Therefore, French administrators likely perceived the rise of a defiant métis community in Saint-Louis as a threat to colonial rule. While the actions of these métis may have been sometimes opportunistic and not fully supported by Africans, one should not assume that the métis always acted in line with the interests of French merchants and French authorities.

The Operation of the Bank of Senegal under French Colonization

The Bank of Senegal was not just a commercial bank but also an issuing bank. As such, it fulfilled the role of monetization in the colony. The banknotes issued by each French colonial bank were printed in Paris and were exchangeable at par with French metropolitan francs. Footnote 17 Nevertheless, these currencies circulated only within the respective colonies and were known as local francs. Upon their arrival in Senegal, local francs were unsealed and checked by the bank’s director in the presence of the Board of Administrators. The banknotes bore the signatures of the director, auditor, and cashier, and the number of each note was registered in a ledger.Footnote 18 Unlike the currency boards established in British colonies in 1912, the Bank of Senegal could issue notes beyond the sum it held in specie, as long as it issued less than three times this sum. On the other hand, total liabilities on the bank’s balance sheet could not exceed three times the amount of the bank’s capital.

At first, the Bank of Senegal issued banknotes in denominations of 25, 100, and 500 francs. The convertibility of these notes into specie was guaranteed, and the notes bore the following inscription: Il sera payé en espèces, à vue au porteur (it will be paid in cash, in sight of the bearer). Compared to the five-franc silver coin, the most popular coin used in commerce, these denominations were large. Therefore, local merchants often complained that they could not return change to clients who paid in banknotes.Footnote 19 For this reason, the bank was authorized to issue five-franc notes in 1874, but these notes could be exchanged for coins only in batches of twenty-five francs.Footnote 20 Five francs was worth, as of 1870, the equivalent of 20 kilograms of shelled groundnuts for export or 3.5 days’ salary for local staff, such as a print worker employed in the administrative department.

The demand for coins continued to be much greater than the demand for notes. Among the reasons for this preference was a lack of trust in the durability and value of the notes. African farmers in Senegal rarely accepted banknotes, demanding silver coins instead as payment for their harvests. Banknotes could easily be damaged by insects or by the harsh climate of West Africa. Moreover, the cours forcé introduced in 1870, which suspended the convertibility between banknotes and specie in a bid to ease the financial crisis brought on by the Franco-Prussian War, further eroded people’s trust in banknotes.

The cours forcé was in effect in metropolitan France until 1875 and in Senegal until 1878. Some incidents relating to this policy provide insights into the role of the bank in the Senegalese economy, as well as Maurel & Prom’s dissatisfaction with the bank’s management. The procurement of silver coins was essential for purchasing groundnuts, which had become Senegal’s most important cash crop by the second half of the nineteenth century. Metropolitan French merchants obtained silver coins in France by paying a premium—3 to 4 francs for every 1,000 francs—and transported the currency to Senegal on their own boats.Footnote 21 Maurel & Prom also adopted this approach. Meanwhile, governmental institutions obtained local banknotes from the Bank of Senegal in exchange for treasury bills sent from Paris by the Ministry of the Navy and Colonies. These local francs were used for remuneration and procurement. The employees who received these notes spent them at local stores, and as a result, banknotes accumulated in the hands of merchants in the colony. However, since Africans did not accept banknotes for their produce, merchants could spend these notes only when they imported new merchandise from France, a transaction which required a specified settlement procedure conducted through a designated credit institution in Paris, the correspondent bank. Nevertheless, to prevent the account opened at the correspondent bank from turning negative, the amount of remittances from the colony to metropolitan France was not initially allowed to exceed the amount transferred from metropolitan France to the colony. Thus, merchants in Senegal who held banknotes often had no choice but to keep these notes in their possession. Maurel & Prom, claiming that this problem was caused by an oversupply of banknotes, called for a reduction in the issuance of banknotes by more than half and simultaneously petitioned the French government to abolish the cours forcé (Péhaut Reference Péhaut2014:155).

The complaints filed by Maurel & Prom suggest two things. First, contrary to Dieng’s assertion, at least at this point in time, the bank was not managed as the largest shareholder wanted it to be. Second, Maurel & Prom was seeking a reduction in the money supply. This second suggestion does not seem unreasonable from a macroeconomic perspective, but it may have aroused Dieng’s criticism because it would lead to a reduction in the credit line and make it difficult for local merchants to access bank credit. While the banknotes issued by sub-Saharan Africa’s first issuing bank were not popular, the Bank of Senegal’s function as a commercial bank was arguably significant. The services most in demand by the local economy were the bank’s credit facilities and its role in conducting import-export transactions between the colony and metropolitan France. The bank’s credit facilities allowed small and medium-sized local businesses to access credit in local francs and make payments for trade carried out with other regions. The bank’s main customers were these local merchants and the colonial government, which needed local francs as the colonial state became institutionalized.

To provide credit across the local economy, the bank discounted commercial bills that were endorsed by two creditworthy cosigners living in the colony, who served as guarantors.Footnote 22 According to shareholders’ meeting reports, the discount rate ranged from 6 to 8 percent. The bank also provided credit in the form of collateral loans at an 8 to 9 percent interest rate. Silver and gold objects, merchandise, and stocks could be pledged as collateral, and indigenous people often obtained the francs needed to import foreign goods by depositing their silver and gold. Since some of the clients were illiterate, however, letters stipulating repayment dates were often ineffective. Loans that were not repaid remained on the bank’s balance sheet as nonperforming loans. Therefore, the bank often had to sell off collateral before the total amount of nonperforming loans, including interest, exceeded their book value.Footnote 23

The exchange business offered by the bank involved two operations: remise and émission (or tirage) services, which involved crediting and debiting the bank’s account at the designated credit institution in France. These operations were conducted through the Central Agency of Colonial Banks in Paris and the designated institution—initially the Bank of France, then (after 1874) the National Discount Bank of Paris (Comptoir national d’escompte de Paris [CNE]). The balance of the account opened at the designated credit institution is equivalent to what is now called the international payments position.

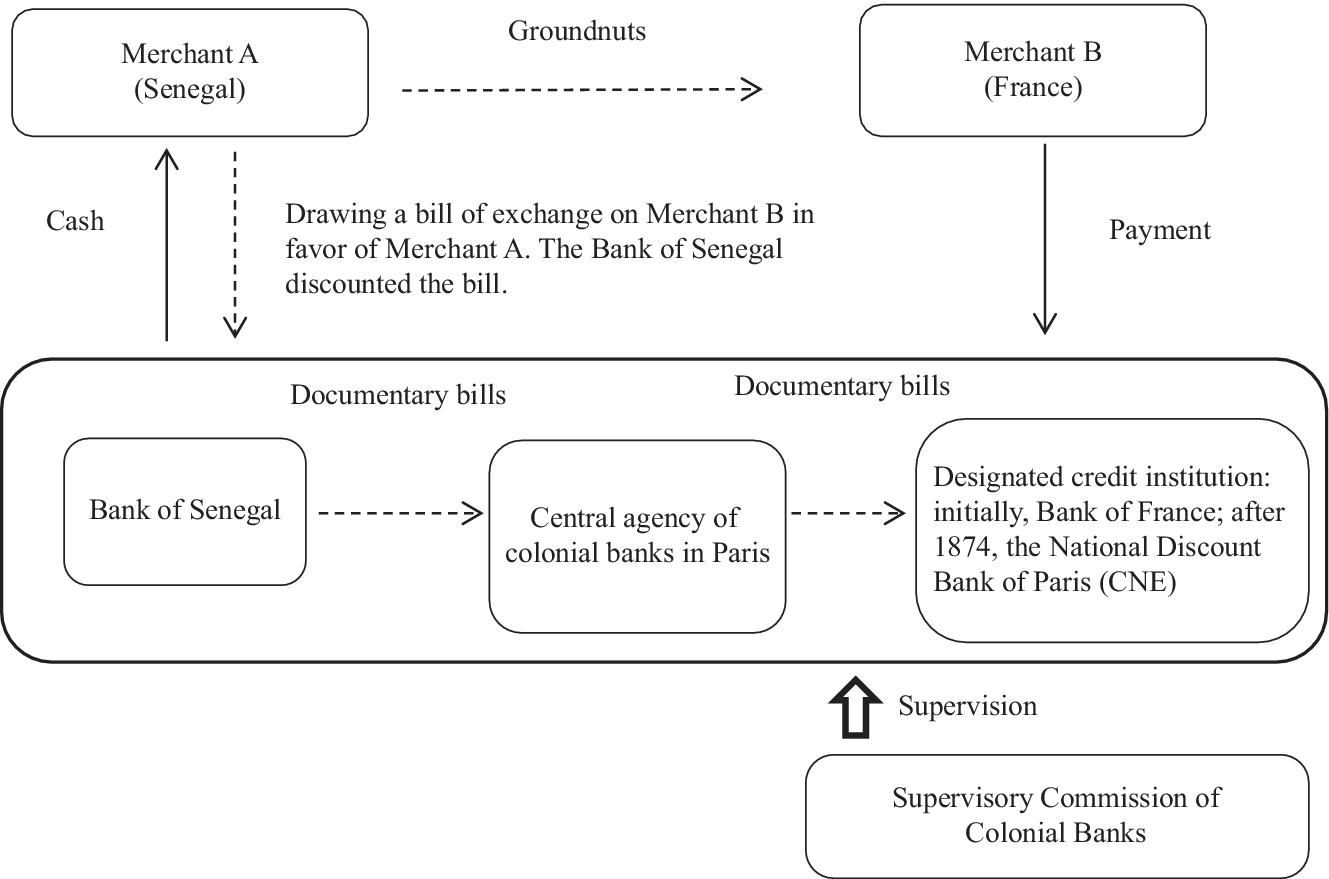

Figure 1 illustrates a remise operation occurring through the Central Agency of Colonial Banks and the designated credit institution. Suppose that Merchant A in Senegal exported groundnuts to Merchant B in France. In this case, Merchant A would be required to draw a bill of exchange payable by Merchant B in favor of Merchant A. Bills had a maturity period of 90 days (or sometimes 120 days). Next, the drawer (Merchant A in this case) asked the Bank of Senegal to endorse the bill. In turn, the bank paid the corresponding amount to Merchant A in local francs. Subsequently, a copy of the bill was sent to Merchant B in France via the Central Agency of Colonial Banks in Paris, and Merchant B received it in exchange for his payment through the designated credit institution. This bill allowed Merchant B to collect the groundnuts, and the amount paid in metropolitan francs was credited to the Bank of Senegal’s account at the designated institution. The financial transactions between metropolitan France and the colonies were supervised by the Supervisory Commission of Colonial Banks in Paris.

Figure 1. Financial transactions involved in exports from Senegal to France. Source: Masaki (Reference Masaki2015:50).

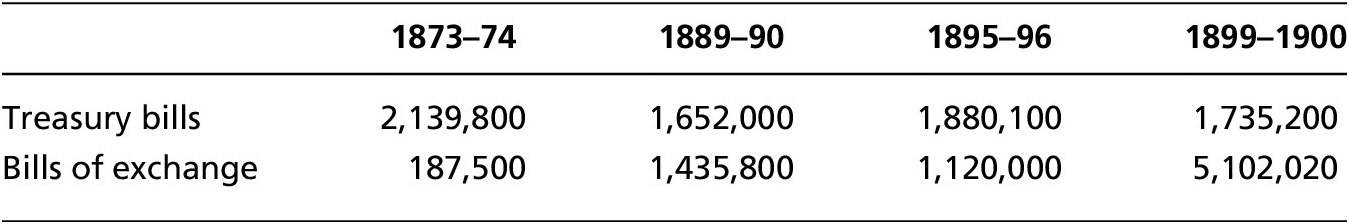

Although the remise operation was similar to the trade settlements used today, the remise operation conducted by public authorities was unique. Public authorities in Senegal procured local francs in exchange for treasury bills issued by the Ministry of the Navy and Colonies or the colonial government. After providing local francs to the bearers of these bills, the bank endorsed the bills and sent them to the designated credit institution in France. In exchange for the bill, the French Treasury credited the corresponding amount in metropolitan francs to the bank’s account at this institution (see Figure 2). Table 1 shows that, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the total amount of remise transactions made by the government was initially much larger than that of private entities. However, private transactions grew rapidly and became dominant by the end of the nineteenth century. The slowdown in the growth of public remise operations could have been caused by the launch of the postal money transfer service in Senegal in 1874 (Masaki Reference Masaki2021). In the colonies, postal money transfer services were executed through Treasury offices.

Figure 2. Financial transactions using money orders (mandats) and treasury bills (traites de trésor). Source: Author.

Table 1. Composition of remises (in francs). Source: Reference du SénégalBanque du Sénégal, CROB, annual volumes.

Émission in the private sectors was technically the opposite of remise, but it was conducted slightly differently. Suppose that Senegalese Merchant C in Saint-Louis needed to pay for his imports from French Merchant D living in Paris (see Figure 2). In this case, initially, the designated institution in Paris did not discount the bills of exchange payable by Merchant C—presumably because agents in Senegal did not have a high credit standing in France. Instead, Merchant C could buy a money order (mandat) in the exact amount in local francs at the Bank of Senegal and send it to Merchant D in France (Amaïzo Reference Amaïzo2001:120–21). When presented with the money order, the institution paid the corresponding amount in metropolitan francs to Merchant D by debiting the account of the Bank of Senegal.

Any person living in Senegal could send money to metropolitan France using a money order. Clients who requested the issuance of a money order paid a commission known as prime, which was a small percentage of the total amount of the remittance. Although the prime rate varied depending on the payment conditions, the prime was kept low in Senegal. For instance, in 1869, the prime for a money order (payable at sight for amounts up to 100 francs and within six days for amounts from 100 to 100,000 francs) was only 1 percent.Footnote 24

The Bank of Senegal also used money orders to obtain silver coins from metropolitan France. In this case, the bank requested the dispatch of silver coins by issuing a money order to the designated credit institution through the Central Agency of Colonial Banks.Footnote 25 All costs to dispatch silver coins were debited from the bank’s account at the institution in Paris. The Central Agency of Colonial Banks supervised this dispatch and carried out the necessary procedures on behalf of the bank in Paris.

Accordingly, all payments to and from metropolitan France through the Bank of Senegal were credited to or debited from the bank’s account at the designated credit institution in Paris. The colonial bank was prohibited from incurring a deficit balance in its Bank of France account but was allowed to do so at the CNE, the institution that replaced the Bank of France in the mid-1870s.Footnote 26 Moreover, the account at the Bank of France did not bear interest, but the account at the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (CDC), a public investment bank established in 1816, was an interest-bearing account. Thus, the Bank of Senegal started to manage its assets more efficiently by transferring a part of them from its account at the Bank of France to the CDC in 1867.Footnote 27 An agreement between the Bank of Senegal and the CNE fixed the overdraft limit based on the amounts of assets that the bank deposited at the CDC. In 1897, the authorized overdraft limit was 420,000 francs.Footnote 28

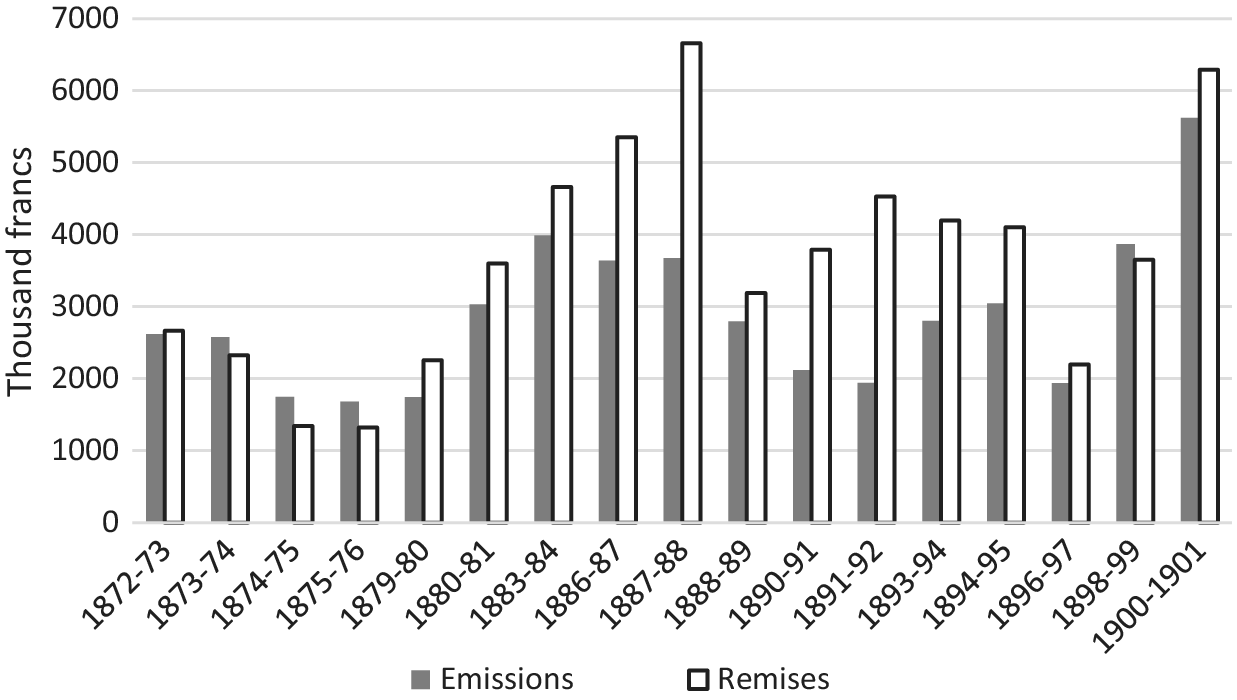

Figure 3 shows the evolution in the amounts of émissions and remises for the period between 1872 and 1901. Although data for certain years are missing, the figure suggests that the credited amount was generally larger than the debited amount, and the Bank of Senegal did not face a serious overdraft problem. This fact was ironically due to the massive monetary transfers by the French Treasury to the colonial government. In the late nineteenth century, however, the number of silver coins sent from France to Senegal began to soar, spurred by the expansion of groundnut production. This influx often caused a debit balance. Table 2 indicates that during the period from 1896 to 1897, the total amount of remises was larger than that of the émissions. However, because of the debit balance rolled over from the previous year and the remittance of silver coins, the Bank of Senegal incurred a debit balance of 1,290,573.85 francs in its account at the CNE.

Figure 3. Changes in the amount of émissions and remises. Source: Commission de surveillance des banques coloniales, Rapport au président de la République sur les opérations des banques coloniales pendant l’exercice, annual volumes.

Table 2. Balance of the Bank of Senegal’s account at the CNE, 1896–1897 (rounded to the nearest few points). Source: Banque du Sénégal, CROB, 1897-98, p. 18, ANS, Q39.

When the colonial bank had a debit balance beyond the authorized amount in its CNE account, the fee (prime) charged for money orders was raised. In principle, the colonial franc was supposed to be exchanged at par with French metropolitan francs. However, a 5 percent prime technically indicated the depreciation of the local franc by altering the exchange rate from 1.00 local colonial franc per 1.00 metropolitan franc to 1.05 local francs per 1.00 metropolitan franc (Schnakenbourg Reference Schnakenbourg1991:38–43). However, the prime for the Bank of Senegal was still very low; from 1896 to 1897, it stood at 1.5 percent for money orders of up to 100 francs payable at sight, and 1 percent for orders above one hundred francs payable within 15 days after presentation. Compared to fees of 15 to 30 percent recorded by the Bank of Guadeloupe in the same period, the prime in Senegal was almost negligible.Footnote 29 The lower fees at the Bank of Senegal might suggest that the authorities controlling these two banks had different approaches with regard to the overdraft limit. As already stated, the Bank of Senegal was not allowed to have a large overdraft, whereas the Bank of Guadeloupe was able to incur large deficits.

The practice seems to bear out a broader logic. The Bank of Senegal was eager to procure as many coins as possible in order to expand its business. However, the bank found it difficult to obtain a sufficient number of silver coins from the CNE due to tight overdraft regulations, as indicated in a letter sent by the Bank of Senegal’s director, Henri Nouvion, in October 1898.Footnote 30 The Bank of Senegal’s overdraft limit on its account in Paris meant that the bank could not procure a large number of silver coins from France or remit as much money as it would like from Senegal to metropolitan France, which may be reasons why large French merchant companies such as Maurel & Prom did not use the bank’s exchange services.

The Bank of Senegal, French Colonization, and Economy-Building

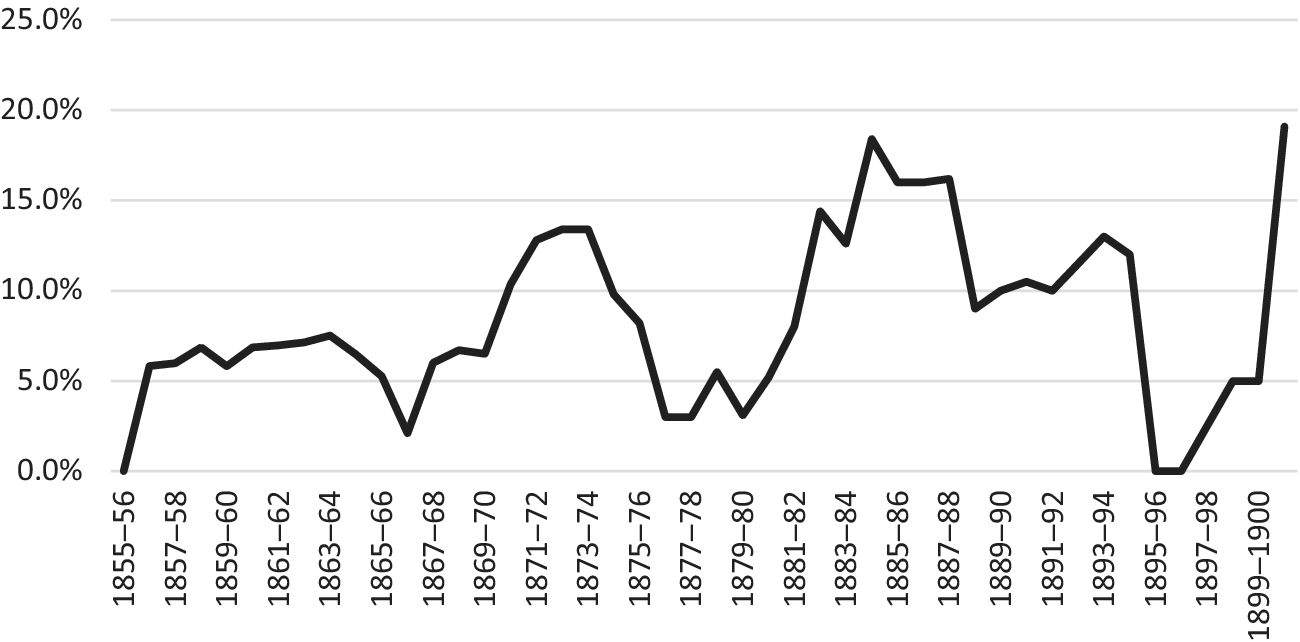

The facts will suggest different conclusions if we shift the perspective. This section examines whether the Bank of Senegal actually performed poorly, as has been widely claimed, and discusses its role in colonization and Senegalese economy building. Figure 4 shows the changes in the bank’s annual dividend rates compared to the face value of a share (500 francs) from the bank’s establishment to its closing. This figure confirms that the bank paid dividends to shareholders exceeding 5 percent of par value in most fiscal years, which was the minimum line shareholders expected.

Figure 4. Dividend rate compared to the face value of a share (500 francs). Source: Author’s calculation based on Goumain-Cornille (Reference Goumain-Cornille1903).

Table 3 shows the bank’s financial statement dated June 30, 1897, the closing date of the bank’s worst accounting year. That year, the bank set aside 400,000 francs as special reserves, as required by the French Ministry of Finance due to its having accrued 415,000 francs in bad loans. Of this amount, a total of 300,000 francs was owed by Gaspard Devès and his son Justin II, whose firm went bankrupt in 1895.Footnote 31

Table 3. Balance sheet of the Bank of Senegal on June 30, 1897 (rounded to the nearest few points). Source: Banque du Sénégal, CROB, 1896-97:33, ANS, Q39.

In the mid-1890s, amid rising political tensions between the colonial administration and the métis community, the colonial authorities found a number of cases of misconduct involving members of the Devès family. In 1896, the authorities removed the director of the Bank of Senegal, Charles Molinet, citing his authorization of credits totaling 322,000 francs to Gaspard Devès and his son, despite his being well aware that their firm was going bankrupt. Molinet was further accused of sanctioning the acceptance of bank notes underwritten by his wife and his brother-in-law, and replacing their signatures with that of his daughter, who lacked financial resources (Jones Reference Jones2013:166). Manchuelle suggested that Charles Molinet was a strong supporter of Louis Descemet (Reference Manchuelle1984:479).

The supervisory commission of colonial banks also discovered that many bills had not been properly endorsed by two creditworthy cosigners or had not been renewed for several years (Renaud Reference Renaud1899:211). Based on this accusation, the Ministry of the Colonies barred the bank from distributing dividends. Jones (Reference Jones2013:162–69) suggested that the colonial administration exposed these scandals due to its increased scrutiny of métis politicians, who were gaining support from the African community. Yves Péhaut (Reference Péhaut2014:157) also noted that Emile Maurel, the first son of Hilaire Maurel, aimed to rectify questionable practices at the Bank of Senegal and demanded the dismissal of Molinet, the bank’s director, in 1896.

Despite these scandals, the Bank of Senegal recorded approximately 78,200 francs in profit in 1896–97.Footnote 32 As of June 30, 1897, the bank had 3,304,464 francs in assets—representing a 6.2-fold increase over thirty years—while satisfying the two main conditions for its operation: that the value of issued notes be kept below three times the amount of specie, and that total liabilities not exceed three times the amount of capital. The bank’s balance sheet shows that the dispatch of silver coins from Paris provided the bank with a sufficient stock of coins to prepare for the start of the groundnut harvest season, even though this resulted in a large debit balance in the Bank of Senegal’s account at the CNE.

The bank’s business expanded over time. French authorities increased the bank’s capital from the initial 230,000 to 300,000 francs in 1874 and then to 600,000 francs in 1888. The bank’s note-issuing privilege, originally granted for twenty years, was renewed in 1874 for another twenty years and annually after 1894. Furthermore, a regulation introduced in 1874 allowed the bank to lend money to public institutions. The bank opened a new branch in Gorée in 1871 which it transferred to Dakar in 1884. In 1899, another branch opened in Rufisque, which was expanding as a center of groundnut production. For the years 1895–96, the ratio of the bank’s total turnover (discounts, loans, advances, and exchange transactions) to its capital ranked second after the Bank of Guyane (French Guiana) among the five colonial banks.Footnote 33

Although the bank appears to have remained sound despite the scandals and crises it had to confront, it nevertheless cannot be denied that its small capital posed an obstacle to its expansion. For example, in 1897, the value of Senegalese imports from and exports to France amounted to 23,524,535 francs and 13,555,969 francs, respectively.Footnote 34 On the other hand, as shown in Table 2, the émission and remise operations carried out via the bank’s account at the CNE between July 1, 1896, and June 30, 1897, show amounts of 1,937,757 and 2,195,700 francs. These figures indicate that the bank was involved in only 8 to 16 percent of Senegal’s total imports from and exports to France, leading to the criticism that French-based firms had bypassed the Bank of Senegal (Dieng Reference Dieng1982:44).Footnote 35 However, one could also advance alternative arguments. Debits from the Bank of Senegal’s account at the designated credit institution in France were constrained by the amounts credited. Therefore, if major shareholders of the bank truly wished to exclude local merchants from the Bank of Senegal’s credit facilities and exchange services, they could have done so through their own exclusive use of its banking services, but this option does not appear to have been chosen.

Conclusions

Although the Bank of Senegal was the first issuing bank established in sub-Saharan Africa, its banknotes were unpopular and its role in colonial monetization limited. Nevertheless, the bank contributed to the local economy and French colonization by providing important financial services. Its “modern” financial services helped métis and African entrepreneurs to establish business ventures and buy property without relying on European merchants (Jones Reference Jones2013:166). These ventures allowed them to emancipate themselves from the dominance of the colonial trading companies (Thiam Reference Thiam2007:117–25). The prosperity of the local merchants led to the prosperity of the colony, a situation that ironically also served the French and colonial governments. In addition, the bank offered local francs in exchange for treasury bills to the colonial administration and provided loans for colonial development projects. Except for a time when silver was scarce in metropolitan France, the bank also supplied the silver coins required to purchase groundnuts from African farmers and enabled the colonial government to expand French influence on the groundnut “frontier.” Moreover, the bank integrated Senegal’s economy into the world economy with the help of a settlement system established between the metropolitan and colonial currencies, while ensuring that growth and recessions in the colonial economy did not directly affect the economy of metropolitan France.

While the Bank of Senegal certainly helped French colonialization in Senegal, it is difficult to assert, as Dieng does, that its largest shareholder, Maurel & Prom, manipulated the bank from the beginning in order to disadvantage its rivals (Reference Dieng1982:43). Circumstances changed in the mid-1890s, however, when Hilaire’s son Emile Maurel appointed Henri Nouvion, an employee of the Bank of France, as the director of the Bank of Senegal after the Gaspard family and Molinet were dismissed. In 1901, Maurel became the president of the newly created Bank of West Africa (Banque de l’Afrique Occidentale, BAO) and succeeded in preparing articles of association that better reflected the views of the major French shareholders and excluded Africans from decision-making.Footnote 36

The findings of this study suggest that the Bank of Senegal, along with the General Council and French National Assembly elections, was also an arena for the political struggles of the métis merchants in Senegal. Around the time AOF was established, Gaspard Devès and his associates, who had close ties to Africans in the interior, had been forced out of the bank. This outcome probably suited the French government’s aim to consolidate its control over the colony. Furthermore, around 1912, the temporary cooperation among métis against the colonial government collapsed. Two sons of Gaspard Devès, Justin II and François, broke with François Carpot and recommended Henri Heimburger, a Parisian lawyer who had loyally served their interests in metropolitan France but knew little about Senegal, to become a candidate for a seat in the French National Assembly (Johnson Reference Johnson1966:244, 1971:106–22). It was as if they were no longer acting for the prosperity of Senegal but for themselves. At that point, according to G. Wesley Johnson (Reference Johnson1966), Devès, Carpot, and the merchant métis, who maintained old-fashioned politics, lost the support of many young Senegalese. These factors may have distorted the understanding of the bank’s operation and the métis contribution to the establishment of a modern financial system in Senegal.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Yasuo Gonjo (権上康男) (1941–2021) for his valuable advice and detailed comments in the early stage of this research and for his many kindnesses extended to me in his later years. I would also like to thank Gerold Krozewski and the anonymous reviewers, and the participants who kindly commented on my papers given at a workshop in Osaka (June 20, 2019, Osaka University), the 14th African Economic History Network (October 22, 2019, Universidad de Barcelona), and 64th Annual meeting of African Studies Association (November 19, 2021, online). This research is supported by three grants: 16K03771 and 20K01805 PI: Toyomu Masaki, and 19H01513 PI: Takeshi Nishimura, from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI).