Introduction

Asteroid impacts represent an extreme among natural disasters, inducing rapid and sharp environmental perturbations with important implications for the biosphere (Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Smit, Lowrie, Asaro, Margolis, Claeys, Kastner and Hildebrand1992; Toon et al. Reference Toon, Morrison, Turco and Covey1997). After the Chicxulub asteroid impact (Yucatan, Mexico) at the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) boundary (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand, Penfield, Kring, Pilkington, Camargo, Jacobsen and Boynton1991), a cloud of dust and fine ejecta scattered and contaminated the atmosphere, land, and oceans (Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Alvarez, Asaro and Michel1980; Smit and Hertogen Reference Smit and Hertogen1980). The cloud of pulverized impact material at Chicxulub was deposited slowly (probably over a few years), forming a thin (few millimeters) airfall layer evident in deep-marine sediments worldwide, with anomalous concentrations of iridium and other platinum-group metals, nickel-rich spinels, shocked quartz, and altered microtektites (Smit Reference Smit1990; Robin et al. Reference Robin, Boclet, Bonte, Froget, Jehanno and Rocchia1991). The Chicxulub impact caused the blockage of sunlight, the inhibition of the photosynthesis, disruption of food chains, a sudden drop in global temperature, destruction of the ozone layer, and the production of toxins and acid rain (Smit and Romein Reference Smit and Romein1985; Hsü and McKenzie Reference Hsü and McKenzie1985; Pope et al. Reference Pope, Baines, Ocampo and Ivanov1997; Gerasimov Reference Gerasimov2002; Ocampo et al. Reference Ocampo, Vajda and Buffetaut2006; Alegret et al. Reference Alegret, Thomas and Lohmann2012; Bardeen et al. Reference Bardeen, Garcia, Toon and Conley2017), initiating one of the greatest mass extinctions in the history of life (Schulte et al. Reference Schulte, Alegret, Arenillas, Arz, Barton, Bown, Bralower, Christeson, Claeys, Cockell, Collins, Deutsch, Goldin, Goto, Grajales-Nishimura, Grieve, Gulick, Johnson, Kiessling, Koeberl, Kring, MacLeod, Matsui, Melosh, Montanari, Morgan, Neal, Nichols, Norris, Pierazzo, Ravizza, Rebolledo-Vieyra, Reimold, Robin, Salge, Speijer, Sweet, Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Vajda, Whalen and Willumsen2010).

In the earliest Danian oceans, a dark-clay bed was deposited above the K/Pg airfall layer under conditions of global climatic warming and alterations in oceanic productivity (Hsü and McKenzie Reference Hsü and McKenzie1985; D’Hondt et al. Reference D’Hondt, Donaghay, Zachos, Luttenberg and Lindinger1998; D’Hondt Reference D’Hondt2005; Coxall et al. Reference Coxall, D’Hondt and Zachos2006; Birch et al. Reference Birch, Coxall, Pearson, Kroon and Schmidt2016), with some regions showing a sharp decline in export productivity during approximately 2 Myr, and others a constant or rapidly reestablished organic flux from the surface ocean to the deep seafloor (Hull and Norris Reference Hull and Norris2011).

The dark-clay bed also contains high concentrations of heavy metals, which, though lower than in the airfall layer, are higher than in the sediments of the upper Maastrichtian and more modern lower Danian (Smit and ten Kate Reference Smit and ten Kate1982; Dupuis et al. Reference Dupuis, Steurbaut, Molina, Rauscher, Tribovillard, Arenillas, Arz, Robaszynski, Caron, Robin, Rocchia and Lefèvre2001; Hollis et al. Reference Hollis, Rodgers, Strong, Field and Rogers2003). The paleoenvironmental conditions recorded in the dark-clay bed seem therefore to reflect the long-term disruptive effects of the K/Pg impact event, revealing a time in which the ecosystems were starting to recover and oceanic productivity to re-establish itself.

Planktic foraminifera, like other paleontological groups, suffered considerable, but not complete, extinction at the K/Pg boundary event (Smit Reference Smit1982). The cause–effect relationship between the Chicxulub impact and the K/Pg mass extinction has been amply verified (see Smit Reference Smit1990, Reference Smit1999; Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuis2000b, Reference Arenillas, Arz, Grajales-Nishimura, Murillo-Muñetón, Alvarez, Camargo-Zanoguera, Molina and Rosales-Domínguez2006), and the impact theory is correspondingly well established in the scientific community (Schulte et al. Reference Schulte, Alegret, Arenillas, Arz, Barton, Bown, Bralower, Christeson, Claeys, Cockell, Collins, Deutsch, Goldin, Goto, Grajales-Nishimura, Grieve, Gulick, Johnson, Kiessling, Koeberl, Kring, MacLeod, Matsui, Melosh, Montanari, Morgan, Neal, Nichols, Norris, Pierazzo, Ravizza, Rebolledo-Vieyra, Reimold, Robin, Salge, Speijer, Sweet, Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Vajda, Whalen and Willumsen2010). However, other evidence seems to suggest that the massive eruptions of the Deccan Traps, India, could have played an important role in the extinction, or at least in the paleoenvironmental changes that occurred during the Cretaceous/Paleogene transition (Courtillot et al. Reference Courtillot, Feraud, Maluski, Vandamme, Moreau and Besse1988; Chenet et al. Reference Chenet, Auidelleur, Fluteau, Courtillot and Bajpai2007, Reference Chenet, Courtillot, Fluteau, Gérard, Quidelleur, Khadri, Subbarao and Thordarson2009; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Bhowmick, Upadhyay, Dave, Reddy, Jaiprakash and Adatte2011, among others). Recently, Schoene et al. (Reference Schoene, Samperton, Eddy, Keller, Adatte, Bowring, Khadri and Gerch2015) has applied uranium-lead (U-Pb) zircon geochronology to Deccan rocks, showing three main eruptive phases or megapulses, the main one (phase 2) beginning approximately 250 Kyr before K/Pg boundary and lasting 750 Kyr.

The Deccan megapulses have been related to episodes of global warming and/or environmental stress across the K/Pg boundary (Keller and Pardo Reference Keller and Pardo2004; Pardo and Keller Reference Pardo and Keller2008; Punekar et al. Reference Punekar, Mateo and Keller2014, Reference Punekar, Keller, Khozyem, Adatte, Font and Spangnberg2016). Keller et al. (Reference Keller, Bhowmick, Upadhyay, Dave, Reddy, Jaiprakash and Adatte2011) proposed that phase 2 (responsible for ca. 80% of the total volume of Deccan Traps emissions) ended at or near the K/Pg boundary, spanning the last 280 Kyr of the Maastrichtian. Deccan-induced global warming and cooling episodes at the late Maastrichtian seem to be responsible for dwarfing episodes in some planktic foraminiferal species (Keller and Abramovich Reference Keller and Abramovich2009; Omaña et al. Reference Omaña, Alencáster, Torres Hernández and López Doncel2012; Petersen et al. Reference Petersen, Dutton and Lohmann2016), migrations (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Wright and Miller2001), and regional assemblage changes (Keller Reference Keller2003), however, without a significant decrease in global planktic foraminiferal diversity (Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuis2000a,Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuisb). After the K/Pg boundary, small species began to appear following a model of “explosive” adaptive radiation (Smit Reference Smit1982; Brinkhuis and Zachariasse Reference Brinkhuis and Zachariasse1988; Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2002, Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2004). One of the ancestors of the first Danian species was the opportunistic, triserial genus Guembelitria, which might be the only true survivor (Smit Reference Smit1982, Reference Smit2004). However, the main lineages of planktic foraminifers appearing in the Danian, whose descendants have reached the present day, could have a benthic origin (see Brinkhuis and Zachariasse Reference Brinkhuis and Zachariasse1988; Arenillas and Arz Reference Arenillas and Arz2017). It must be emphasized that there are other relevant taxonomic and phylogenetic models, some of them highly supported among planktic foraminifer taxonomists. Among the most noteworthy proposals are those of Olsson et al. (Reference Olsson, Hemleben, Berggren and Huber1999), Apellaniz et al. (Reference Apellaniz, Orue-Etxebarría and Luterbacher2002), Aze et al. (Reference Aze, Ezard, Purvis, Coxall, Stewart, Wade and Pearson2011), and Koutsoukos (Reference Koutsoukos2014), which suggest that the genus Muricohedbergella was a survivor of the K/Pg extinction event and played an important phylogeny role for being the ancestral form of Danian genera such as Globanomalina, Eoglobigerina, and/or Praemurica.

Abnormal tests have long been reported in recent benthic foraminifera linked to regions with either high environmental variability (e.g., Polovodova and Schonfeld 2008; Ballent and Carignano Reference Ballent and Carignano2008) or human-induced pollution (e.g., Yanko et al. Reference Yanko, Ahmad and Kaminski1998; Samir and El Din Reference Samir and El Din2001; Frontalini and Coccioni Reference Frontalini and Coccioni2008), showing that abnormal variations in morphology are a response to changes in ecological parameters such as temperature, pollution, carbonate solubility, dissolved oxygen, or the occurrence of rapid environmental fluctuations. The long-term effects of Chicxulub impact and the Deccan eruptions probably triggered similar ecological stress conditions, thus inducing similar malformations in planktic foraminiferal tests. Indeed, abnormal planktic foraminifers have been reported right above the K/Pg boundary, mainly in Guembelitria (Coccioni and Luciani Reference Coccioni and Luciani2006). Similar increases in abnormal planktic tests have been observed in warming episodes and episodes of ecological stress, such as the Cretaceous ocean anoxic events (Verga and Premoli Silva Reference Verga and Premoli Silva2002) or the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (Luciani et al. Reference Luciani, Giusberti, Agnini, Backman, Fornaciari and Rio2007). However, studies on the aberrant planktic foraminifers of the K/Pg transition from a taxonomic and paleoenvironmental point of view are still very limited and fragmented.

Abnormalities are formed when the ontogenetic plan of the test is disrupted and this disruption generates an irregular shape in comparison with other specimens of the same species (Murray Reference Murray2006). In recent foraminifera, abnormalities produced during the life and growth of an individual may be due either to mechanical or ecological causes (Boltovskoy and Wright Reference Boltovskoy and Wright1976; Murray Reference Murray2006). In the case of planktic foraminifera, the causes behind test abnormalities may be predation breakages, but abnormal planktic specimens seem to reflect mainly stressful environmental conditions (Montgomery, Reference Montgomery1990; Luciani et al. Reference Luciani, Giusberti, Agnini, Backman, Fornaciari and Rio2007). In addition, abnormalities can also be produced by mutations. The phenotypic consequences of mutations can vary, but in the case of fossil foraminifera, the most interesting ones are those that affect the test morphology. Mutations can cause lethal or physiologically nonfeasible aberrations, but could have also generated new species, probably bringing on the early Danian evolutionary radiation mentioned earlier (BouDagher-Fadel Reference BouDagher-Fadel2012; Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Grajales-Nishimura, Meléndez and Rojas-Consuegra2016).

In this paper, a wide variety of morphological abnormalities in planktic foraminiferal tests from the earliest Danian are described for the first time, mainly from Tunisian sections. We use a quantitative approach to identify changes in the abundance of aberrant tests and correlate them with evolutionary radiations and other shifts recognized in the planktic foraminiferal assemblages across the K/Pg boundary. The main aim is to inquire into the causes that could have triggered the proliferation of aberrant tests before and after the K/Pg boundary mass extinction, and the relation of these causes with the environmental changes induced by the Deccan eruptions and the Chicxulub impact.

Material and Methods

Geological Context and Micropaleontological Sampling

We studied samples from localities considered to be the most expanded and continuous marine K/Pg sections worldwide, such as El Kef, Aïn Settara, and Elles (Tunisia), and Agost and Caravaca (Spain). The El Kef section was chosen to define the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Danian stage, or the K/Pg boundary (Molina et al. Reference Molina, Alegret, Arenillas, Arz, Gallala, Hardenbol, von Salis, Steurbaut, Vandenberghe and Zaghbib-Turki2006), while Caravaca, Elles, and Aïn Settara were chosen as auxiliary sections of the GSSP (Molina et al. Reference Molina, Alegret, Arenillas, Arz, Gallala, Grajales-Nishimura, Murillo-Muñetón and Zaghbib-Turki2009). The K/Pg boundary is defined at the base of the bed informally known as the “K/Pg boundary clay,” specifically at the base of the 2- to 5-mm-thick airfall layer with high concentrations of iridium that coincides with the planktic foraminiferal extinction horizon (Smit Reference Smit1990, Reference Smit1999). The dark-clay bed overlying the K/Pg airfall layer is approximately 100 cm thick in El Kef, with a 50-cm-thick blackish clay overlain by a 50-cm-thick dark gray clay; it continues with 1-m-thick darkened gray marly clay and 60-cm-thick clayey marl, so the dark-clay bed thickness could be 200 cm or more in El Kef. It is characterized by low values of δ13C and CaCO3 content and high total organic carbon (TOC) values (Keller and Lindinger Reference Keller and Lindinger1989). In Aïn Settara, the airfall layer is 5 to 10 mm thick, and the dark-clay bed is approximately 50 cm thick; this is also characterized by low values of δ13C and in CaCO3 content and high TOC values (Dupuis et al. Reference Dupuis, Steurbaut, Molina, Rauscher, Tribovillard, Arenillas, Arz, Robaszynski, Caron, Robin, Rocchia and Lefèvre2001).

For the taxonomic studies, specimens were picked mainly from El Kef and Aïn Settara, where the foraminiferal test preservation is good (excellent at some samples), although specimens from other sections (Elles, Agost, and Caravaca) were used with the aim of conveniently illustrating some of the species and types of normal and abnormal growth morphologies identified in the lower Danian. Specimens considered to be normal forms are those that conform to some type of shape within the theoretical three-dimensional morphospace of serial and spiral foraminifeal tests proposed by Tyszka (Reference Tyszka2006). Taxonomic remarks and a systematic scheme for the normal forms of early Danian planktic foraminiferal species are provided in Supplementary Appendix A and Supplementary Figure 1.

All rock samples studied were disaggregated in water with diluted H2O2, washed through a 63 μm sieve, and then oven-dried at 50°C. The quantitative analyses were based on representative splits (using a modified Otto microsplitter) of approximately 300 specimens per sample, quantifying the relative abundance of both normal and abnormal tests in each group of planktic foraminifera (Tables 1, 2). For the quantitative study, we restudied 39 samples from El Kef and 35 samples from Aïn Settara (see Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuis2000a,Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuisb). The specimens analyzed were mounted on microslides for a permanent record and identification. Planktic foraminifera were picked from the residues and selected for scanning electron microscopy (SEM), using the JEOL JSM 6400 and Zeiss MERLIN FE-SEM of the Electron Microscopy Service of the Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain). SEM photographs of the species considered here are provided in Supplementary Figures 2 and 3. For the illustration of these species, we used, in addition to El Kef and Aïn Settara, other localities characterized by the good preservation of their foraminiferal tests, such as Ben Gurion (Israel), Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) Site 305 (North Pacific), and Bajada del Jagüel (Argentina).

Table 1 Relative abundance (%) of planktic foraminiferal groups considered here and rates of aberrants at the El Kef section. Values for the hypotheses of both pattern A and pattern B are included. A. m., Abathomphalus mayaroensis Zone; P. h., Plummerita hantkeninoides Subzone; H. p., Heterohelix predominance; P. e., Parvularugoglobigerina eugubina Zone; P. s., Palaeoglobigerina sabina Subzone. Samples are presented in centimeters below (−) and above (+) the K/Pg boundary. x, relative abundance <0.3%.

Table 2 Relative abundance (%) of planktic foraminiferal groups considered here and rates of aberrants at the Aïn Settara section. Values for the hypotheses of both pattern A and pattern B are included. A. m., Abathomphalus mayaroensis Zone; P. h., Plummerita hantkeninoides Subzone; H. p., Heterohelix predominance. Samples are stated in centimeters below (−) and above (+) the K/Pg boundary.

Planktic Foraminiferal Biochronology

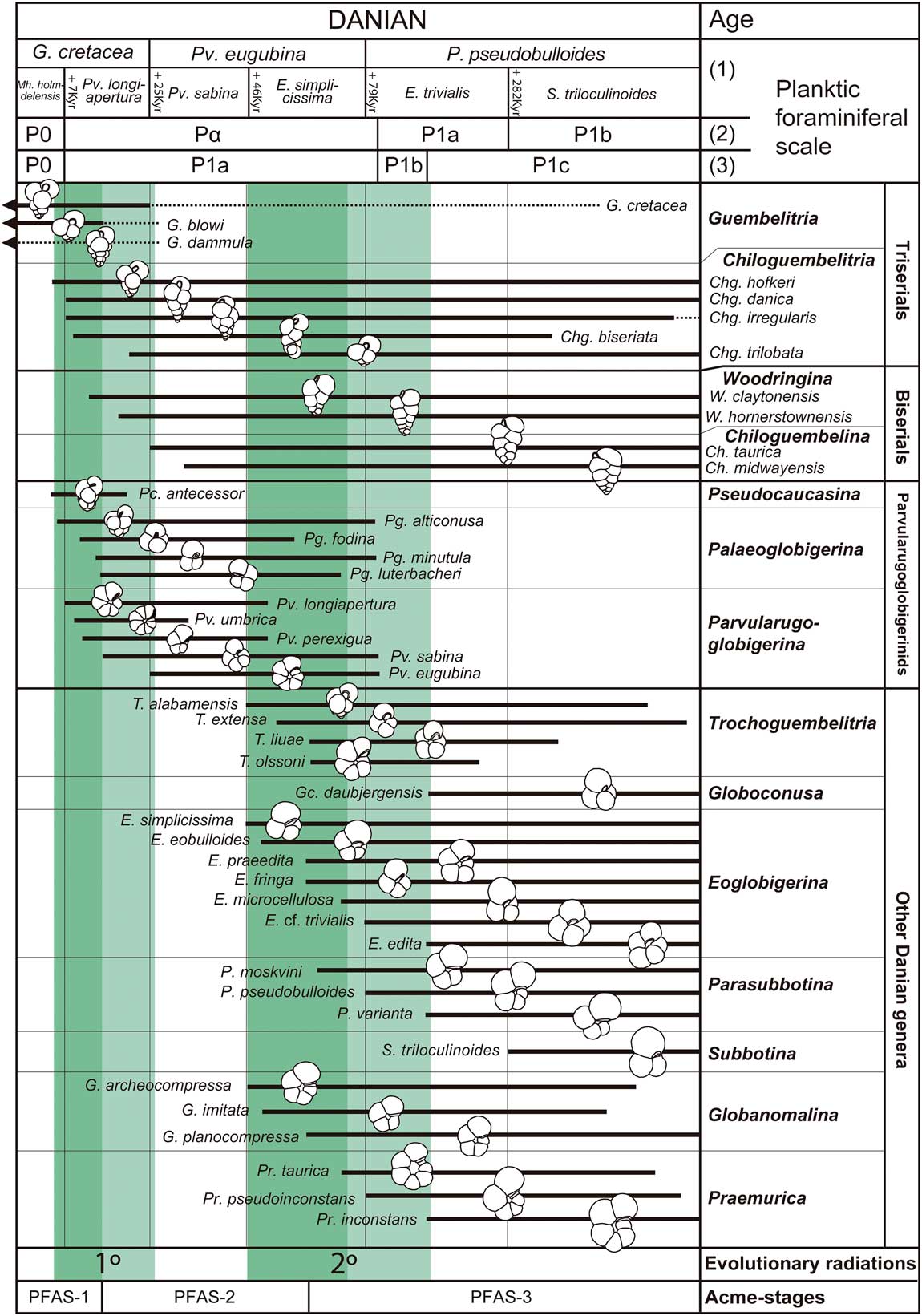

For the Maastrichtian, the biostratigraphic and quantitative study focused mainly on the Plummerita hantkeninoides Subzone, which spans the last 140 Kyr of the Cretaceous according to Husson et al. (Reference Husson, Galbrun, Gardin and Thibault2014). This biozone is defined by the total range of the nominate taxon and is equivalent to the alphanumeric Zone CF1 of Li and Keller (Reference Li and Keller1998). For the lower Danian, we used the biozonation of Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2004), and compared it with those of Li and Keller (Reference Li and Keller1998) and Berggren and Pearson (Reference Berggren and Pearson2005) (the latter recently revised by Wade et al. Reference Wade, Pearson, Berggren and Pälike2011). Their equivalences are shown in Figure 1. The former is based on continuous, complete, and very expanded Tunisian and Spanish K/Pg sections such as El Kef, Aïn Settara, Elles, Caravaca, Agost, and Zumaia. It includes six subbiozones: the Muricohedbergella holmdelensis and Parvularugoglobigerina longiapertura Subzones of the Guembelitria cretacea Zone, the Parvularugoglobigerina sabina and Eoglobigerina simplicissima Subzones of the Pv. eugubina Zone, and the Eoglobigerina trivialis and Subbotina triloculinoides Subzones of the P. pseudobulloides Zone. The species ranges illustrated in Figure 1 are based on the stratigraphic distributions verified mainly in the El Kef stratotypic section. Note that the Mh. holmdelensis Subzone is equivalent to Zone P0 of Li and Keller (Reference Li and Keller1998) and Berggren and Pearson (Reference Berggren and Pearson2005), whereas Zone Pα (or P1a of Li and Keller Reference Li and Keller1998) spans approximately the Pv. longiapertura, Pv. sabina, and E. simplicissima Subzones.

Figure 1 Biostratigraphic ranges of the early Danian species analyzed, based mainly on the El Kef and Aïn Settara sections, Tunisia; (1) planktic foraminiferal zonation and calibrated numerical ages of the biozonal boundaries proposed by Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2004); (2) and (3) zonations of Berggren and Pearson (Reference Berggren and Pearson2005) and Li and Keller (Reference Li and Keller1998), respectively; intervals with green shading indicate the first and second evolutionary radiations of the early Danian at El Kef (the shading in dark green indicates high speciation rates; see online version for color); dotted lines indicate uncertain ranges in the case of Guembelitria species (G. cretacea, G. blowi, and G. dammula) in the lower Danian, because these may actually correspond to reworked specimens and/or the ranges of morphologically similar species of Chiloguembelitria (Chg. danica, Chg. trilobata, and Chg. hofkeri, respectively). PFAS, planktic foraminiferal acme-stage.

Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2004) calibrated numerical ages of the biozonal boundaries on the basis of biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic data from Agost, Spain, and the timescale of Röhl et al. (Reference Röhl, Ogg, Geib and Wefer2001), who astronomically calibrated the C29r/C29n reversal at 255 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary. Subsequent radiometric, paleomagnetic, and astronomical dating/calibrations have given different results for the age of the K/Pg boundary as well as the duration of the magnetozones. Taking into account the Geologic Time Scale 2012 (GTS12; Gradstein et al. Reference Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012), which gives an age for the C29r/C29n boundary of 352 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary, the Mh. holmdelensis Subzone would span the first 7 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary, the Pv. longiapertura Subzone from 7 to 25 Kyr, the Pv. sabina Subzone from 25 to 46 Kyr, the E. simplicissima Subzone from 46 to 79 Kyr, the E. trivialis Subzone from 79 to 282 Kyr, and the S. triloculinoides Subzone from 282 to 616 Kyr.

High-resolution quantitative studies of Tethyan sections make it possible to recognize three planktic foraminiferal acme-stages (PFAS) of high biochronological interest across the lowermost Danian in pelagic (oceanic and outer neritic) environments (see Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Grajales-Nishimura, Murillo-Muñetón, Alvarez, Camargo-Zanoguera, Molina and Rosales-Domínguez2006): PFAS-1, dominated by the triserial Guembelitria; PFAS-2, dominated by tiny trochospiral, informally denominated parvularugoglobigerinids (Parvularugoglobigerina and Palaeoglobigerina); and PFAS-3, dominated by biserial Woodringina and Chiloguembelina. Following the GTS12, PFAS-1 would span the first 18 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary, PFAS-2 approximately from 18 to 62 Kyr, and PFAS-3 from 62 Kyr on. A second acme of triserials is identified in the lower part of PFAS-3, that is, in the transition between the Pv. eugubina and P. pseudobulloides Zones (Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz and Gilabert2017). This acme has been attributed to the genus Chiloguembelitria Hofker, Reference Hofker1978, not Guembelitria, and spans approximately from 70 to 200 Kyr according to the GTS12.

Danian Planktic Foraminiferal Evolutionary Radiations

Many new species of trochospiral and biserial planktic foraminifers originated after the K/Pg boundary, as is shown in Figure 1 and described in Supplementary Appendix A. The systematic scheme in Supplementary Figure 1 is a good reflection of the morphological and textural diversity that appeared after the extinction event. As illustrated in Figure 1, the planktic foraminifera evolutionary radiation of the early Danian happened in two pulses (see also Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuis2000a,Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuisb, Reference Arenillas, Arz and Gilabert2017; Arenillas and Arz Reference Arenillas and Arz2017). The first occurred between approximately 5 and 26 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary according to the GTS12, with the appearance of tiny, trochospiral species belonging to the parvularugoglobigerinids (Pseudocaucasina, Palaeoglobigerina, and Parvularugoglobigerina) and biserial taxa (Woodringina and Chiloguembelina), as well as triserial species of the genus Chiloguembelitria (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The second evolutionary radiation occurred between approximately 46 and 110 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary according to the GTS12, giving rise to more ornamented, larger trochospiral species (Supplementary Figs. 1, 3) belonging to Trochoguembelitria, Eoglobigerina, Parasubbotina, Globanomalina, and Praemurica. Other genera appear shortly afterward, such as Subbotina and Globoconusa.

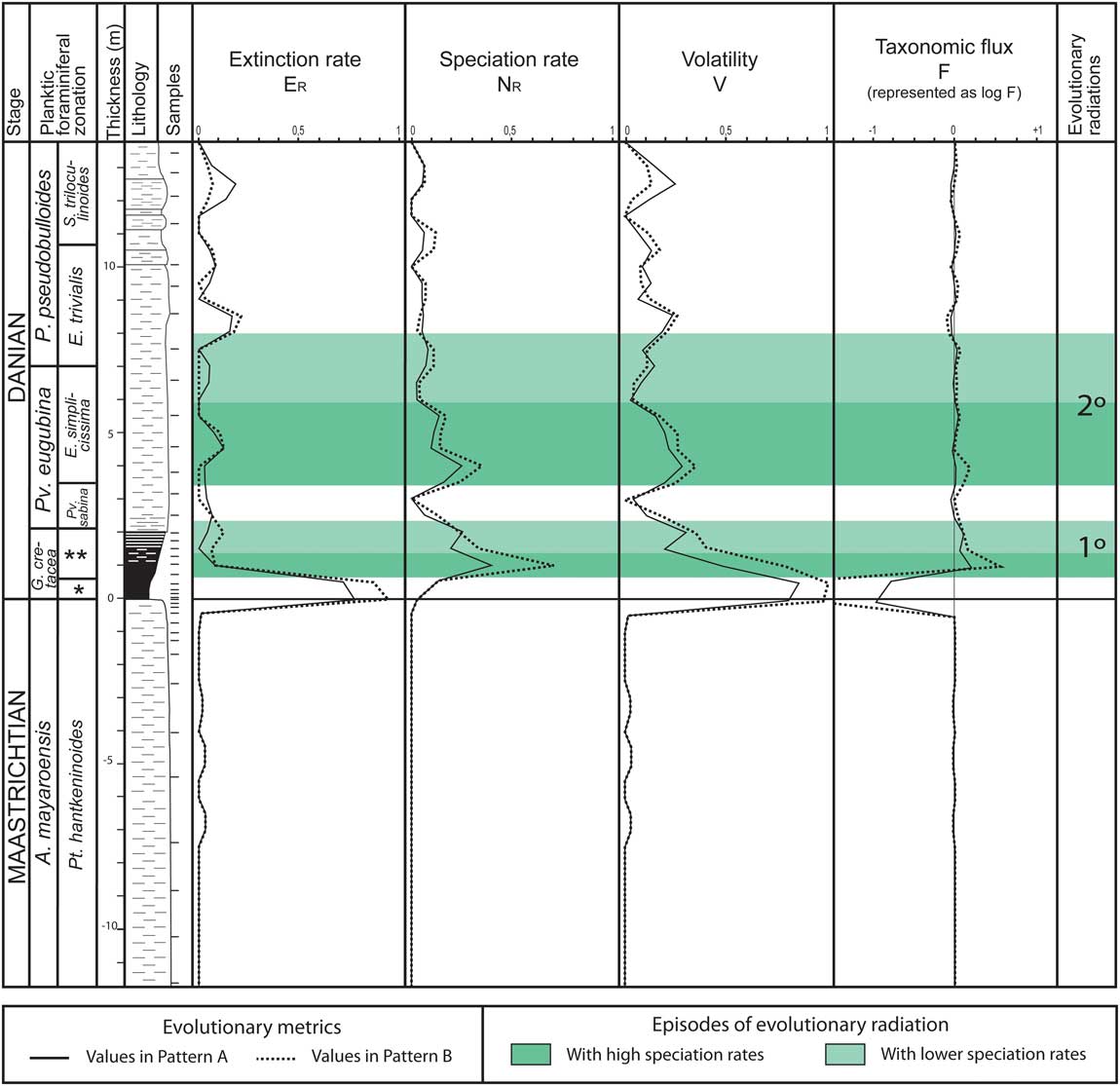

In the present work, the extinction and evolution of planktic foraminifers across the K/Pg boundary at the El Kef section were quantified using the evolutionary model proposed by Dean and McKinney (Reference Dean and McKinney2001), which measures taxonomic turnovers using four metrics (Fig. 2): extinction rate (ER), speciation rate (NR), volatility (V), and taxonomic flux (F). Taxonomic flux F is used to estimate whether there are relative increases (positive values) or declines (negative values) in diversity. The volatility V indicates whether there is evolutionary stability (low values) or increased taxonomic turnover (high values). The method developed by Dean and McKinney (Reference Dean and McKinney2001), which is described in Supplementary Appendix B, was applied to the stratigraphic ranges of planktic foraminiferal species recognized in the El Kef section (Supplementary Fig. 4). The present quantification of the evolutionary pattern is an update of the one already made at El Kef by Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2002), taking into account the taxonomic and biostratigraphic revisions made since then (see Supplementary Appendix A). The metrics were measured under two alternative hypotheses, as already proposed by Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2002): (1) all 16 Cretaceous species identified in lower Danian levels are in situ (pattern A in Supplementary Table 1): Muricohedbergella holmdelensis, Muricohedbergella monmouthensis, Heterohelix globulosa, Heterohelix planata, Heterohelix navarroensis, Heterohelix labellosa, Laeviheterohelix pulchra, Laeviheterohelix glabrans, Pseudoguembelina kempensis, Pseudoguembelina costulata, Globigerinelloides volutus, Globigerinelloides praeriehillensis, Globigerinelloides yaucoensis, Guembelitria dammula, Guembelitria cretacea, and Guembelitria blowi (see Supplementary Fig. 4); and (2) except for two Guembelitria species (Guembelitria cretacea and Guembelitria blowi), all Cretaceous species identified in lower Danian levels are reworked (pattern B in Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 2 Evolutionary metrics (extinction and speciation rates, volatility, and taxonomic flux) at El Kef according to the model of Dean and McKinney (Reference Dean and McKinney2001); solid line, hypothesis of pattern A; dotted line, hypothesis of pattern B; green shading, episodes of evolutionary radiation, with shading in dark green to indicate high speciation rates (see online version for color). *Mh. holmdelensis Subzone (= Zone P0); **Pv. longiapertura Subzone.

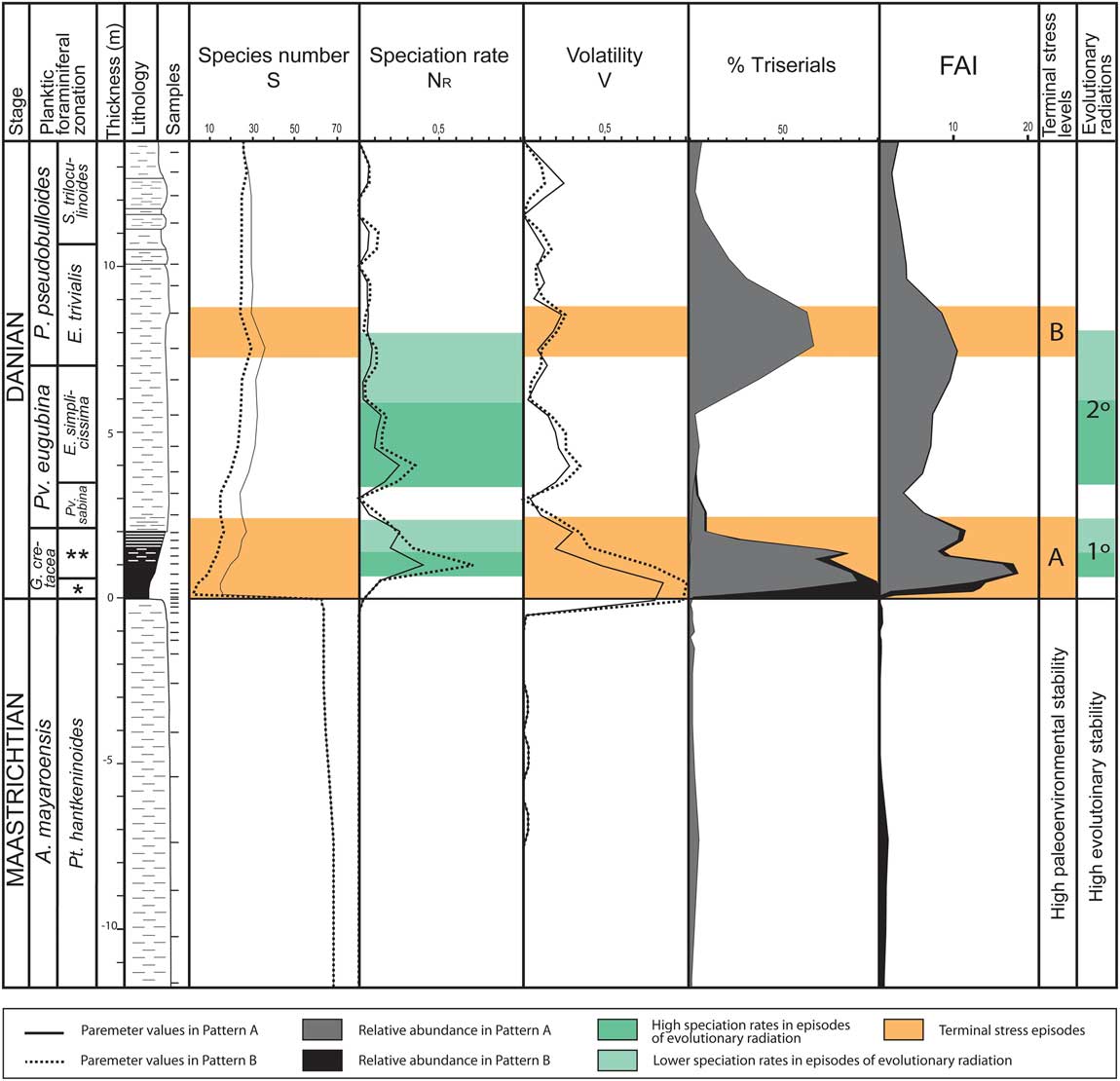

According to these metrics, in both hypotheses (Fig. 2), four main evolutionary episodes were recognized: (1) an extremely high extinction rate coinciding with the catastrophic mass extinction at the K/Pg boundary; (2) a high speciation rate in the Pv. longiapertura Subzone coinciding with the first Danian evolutionary radiation, mainly of parvularugoglobigerinids; (3) a relatively high speciation rate in the E. simplicissima Subzone coinciding with the beginning of the second evolutionary radiation; and (4) a relatively high extinction rate in the basal part of the E. trivialis Subzone coinciding with the parvularugoglobigerinid extinction. Due to these evolutionary episodes, volatility is high at El Kef during approximately the first 200 Kyr of the Danian, which is also reflected by relevant fluctuations in the taxonomic flux. These data contrast with the extremely low volatility in the P. hantkeninoides Subzone of the uppermost Maastrichtian (Fig. 2).

Abnormal Specimens across the K/Pg Boundary

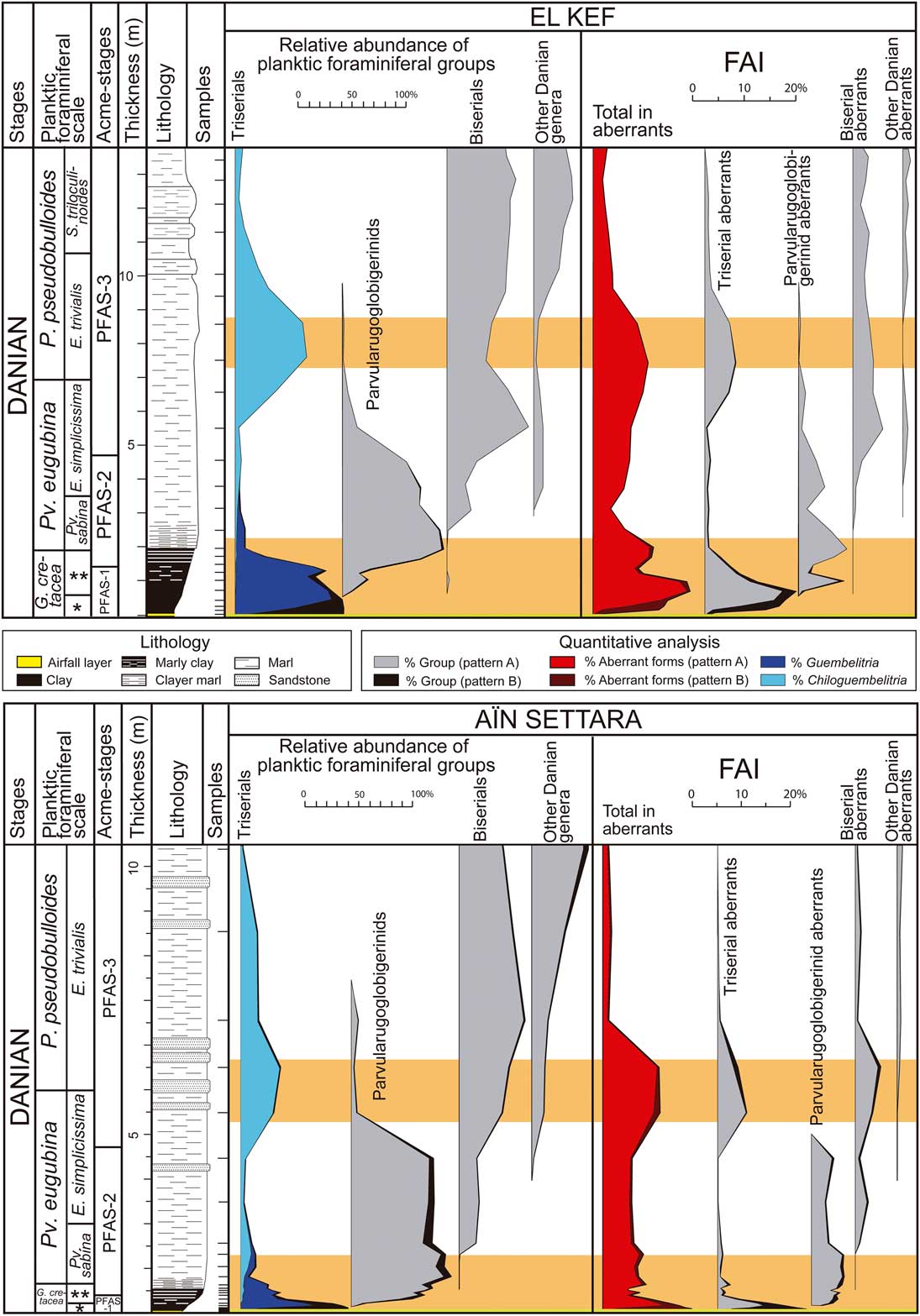

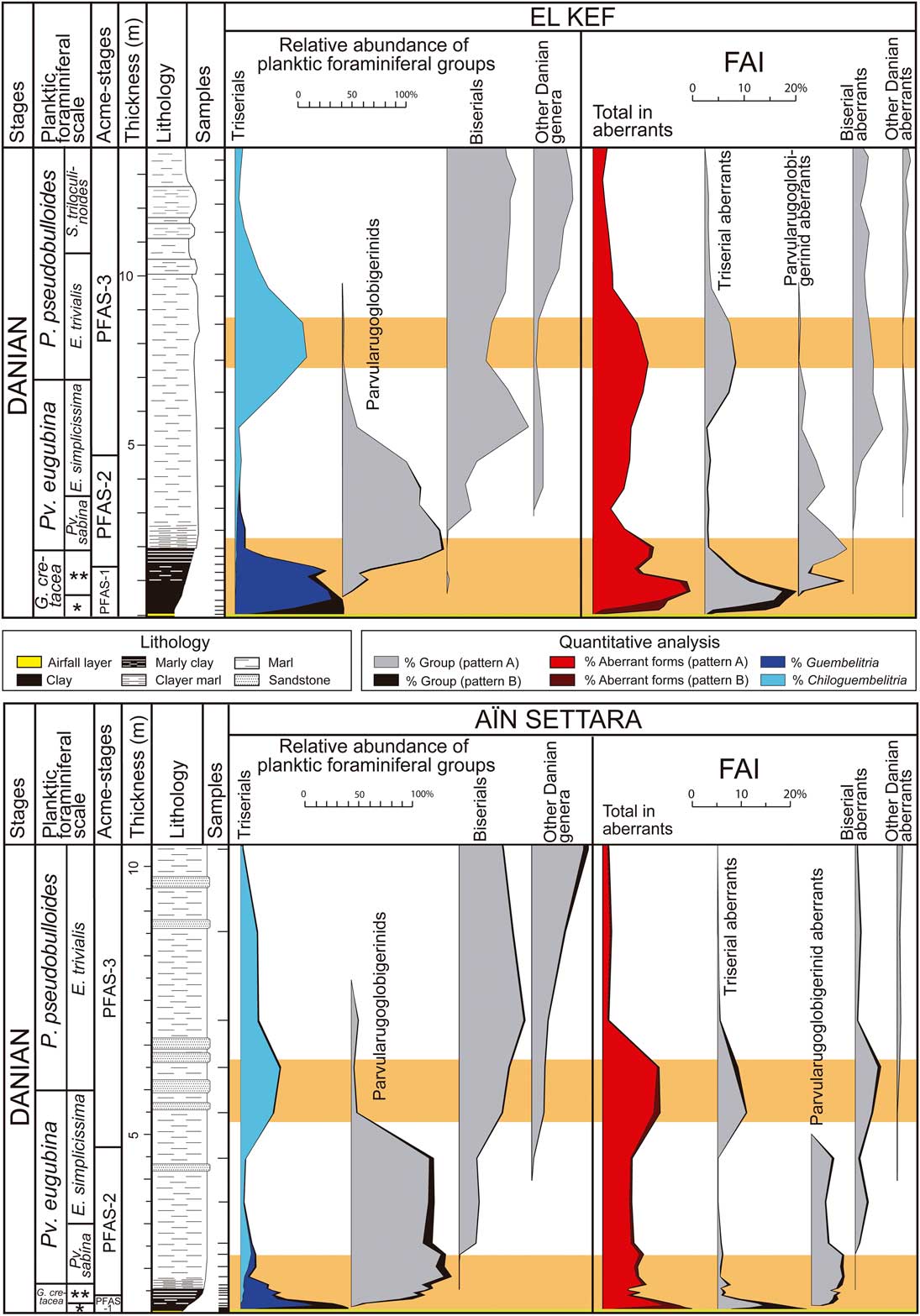

Our quantitative study of planktic foraminifers has revealed a strong proliferation of aberrant forms above the K/Pg boundary in the El Kef and Aïn Settara sections (Fig. 3). At El Kef, the abundance of aberrant tests (Foraminiferal Abnormality Index, or FAI) in PFAS-1 is as high as 18.7% of the total population of planktic foraminifera, of which almost 90% are abnormal forms of the triserial Guembelitria. At Aïn Settara, the abundance of aberrant forms in PFAS-1 reaches over 12%, of which almost 70% are aberrant tests belonging to Guembelitria. These data contrast with the total percentage of aberrant tests in studied Maastrichtian samples (Tables 1, 2), which almost never exceeds 2.5% in either section (except for the basal part of the Aïn Settara section, whose FAI is as high as 3.4–3.6%). These include a few aberrant specimens, mainly of Heterohelix and Pseudoguembelina.

Figure 3 Quantitative stratigraphic distribution of planktic foraminiferal groups and aberrant forms across the K/Pg boundary in the El Kef and Aïn Settara sections. The triserial group includes Guembelitria and Chiloguembelitria; the parvularugoglobigerinids include Pseudocaucasina, Palaeoglobigerina, and Parvularugoglobigerina; the biserial group includes Woodringina and Chiloguembelina; and other Danian genera include Trochoguembelitria, Eoglobigerina, Parasubbotina, Globanomalina, Praemurica, Subbotina, and Globoconusa. Curves with black shading represent the recalculated percentages assuming that, except for Guembelitria, the Maastrichtian specimens found in Danian horizons are reworked (pattern B hypothesis). Intervals with orange shading (see online version for color) represent terminal stress levels according to the model of Weinkauf et al. (Reference Weinkauf, Moller, Koch and Kucera2014). FAI, Foraminiferal Abnormality Index (% aberrant planktic foraminifera). *Mh. holmdelensis Subzone (= Zone P0); **Pv. longiapertura Subzone.

These percentages increase if we assume that the Maastrichtian specimens found in Danian horizons are reworked (pattern B hypothesis), except for two Guembelitria species (curves with black shading in Fig. 3). In this case, the FAI in PFAS-1 reaches almost 20% in El Kef and 18% in Aïn Settara. It should be noted that, except for Guembelitria, the percentages of other aberrant Maastrichtian specimens in the Danian are similar to those estimated for Maastrichtian horizons (Tables 1, 2), in contrast with the strong increase in aberrant tests among the Danian Guembelitria specimens within the dark-clay bed. This suggests that all these Maastrichtian specimens (aberrants and non-aberrants alike) are in fact reworked. A high-resolution biostratigraphic analysis at the Moncada section, Cuba, revealed that, with the exception of Guembelitria species, there were no cosmopolitan, generalist Cretaceous species in the lowermost Danian deposits, not even in Zone P0 and the dark-clay bed (Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Grajales-Nishimura, Meléndez and Rojas-Consuegra2016). This evidence led the authors to suggest that the planktic foraminiferal mass extinction at the K/Pg boundary was more severe and catastrophic than previously suggested and that the presence of Cretaceous species within the lowermost Danian deposits at most K/Pg localities may be the result of normal reworking/bioturbation processes worldwide (see also Huber Reference Huber1996; Kaiho and Lamolda Reference Kaiho and Lamolda1999; Huber et al. Reference Huber, MacLeod and Norris2002). In any case, whether we consider the pattern A hypothesis or that of pattern B, the abundance curves indicate similar trends (Fig. 3).

Aberrant Guembelitria specimens have frequently been classified as Guembelitria irregularis (e.g., Coccioni and Luciani Reference Coccioni and Luciani2006). This species has no doubt been used as a “wastebasket” taxon that also includes the aberrant forms of both Maastrichtian and Danian guembelitriids (see discussion in Arz et al. Reference Arz, Arenillas and Náñez2010). However, we consider here that irregularis is a genuine Danian species, including normal triserial forms (see Supplementary Fig. 1), because the abnormal morphologies among guembelitriids are of another kind. Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Gilabert2017) attributed irregularis to the genus Chiloguembelitria instead of Guembelitria, on the basis of differences in the wall texture and position of the aperture. Chiloguembelitria irregularis groups Danian specimens with twisted triserial arrangements of irregular appearance, corresponding to the irregular morphophase of the model of Tyszka (Reference Tyszka2006). Nevertheless, if these specimens are also counted as abnormal forms, then the FAI during the earliest Danian is even more anomalous, reaching more than 23% in PFAS-1 at El Kef, according to the pattern B hypothesis (Fig. 3).

During the episode PFAS-1, abnormalities are frequent in all planktic foraminiferal groups, suggesting that ecological stress affected all pelagic environments during the early Danian. The FAI in the upper PFAS-1 is high not only in guembelitriids but also in parvularugoglobigerinids; for example, almost 40% of parvularugoglobigerinid specimens from the sample at 97 cm above the K/Pg boundary at El Kef have some type of abnormality. Subsequently, the abundance of aberrant tests decreases during PFAS-2 but remains relatively high in both El Kef and Aïn Settara, at around 3–10% (in both patterns A and B), suggesting that the environmental conditions remained unstable tens of thousands of years after the K/Pg boundary. Another increase in the FAI has been recognized across the boundary between the Pv. eugubina and P. pseudobulloides Zones (mainly in the E. trivialis Subzone, or Subzone P1a), rising to a maximum of 11% (in both patterns A and B) in El Kef and Aïn Settara (Fig. 3). The increase in aberrant forms is more evident among triserial and biserial specimens of the genera Chiloguembelitria, Woodringina, and Chiloguembelina. This interval coincides with the second bloom of triserials in the lower part of PFAS-3 (Fig. 3), in this case caused by Chiloguembelitria and not by Guembelitria. Guembelitria comprised opportunistic species whose relative abundance strongly increased in ecological stress conditions, mainly related to eutrophication episodes (see e.g., Keller and Pardo Reference Keller and Pardo2004). Chiloguembelitria replaced Guembelitria in the early Danian, occupying a similar ecological niche (Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz and Gilabert2017), so its blooms indicate similar conditions of ecological stress. Maxima in aberrant specimens thus seem to coincide with guembelitriid blooms in the early Danian, as occurs in PFAS-1 and the lower part of PFAS-3.

A Compendium of Earliest Danian Abnormal Morphologies

Various types of abnormalities are present among the earliest Danian planktic foraminifers, severely complicating their taxonomic identification in some cases. Abnormal specimens have previously been reported in the lowermost Danian of other localities, mainly among Guembelitria (Coccioni and Luciani Reference Coccioni and Luciani2006) but also among parvularugoglobigerinids (Gerstel et al. Reference Gerstel, Thunell, Zachos and Arthur1986). Double and multiple tests of Parasubbotina and Globoconusa were also described by Ballent and Carignano (Reference Ballent and Carignano2008) in shallow environments of the Cerro Azul section, Argentina.

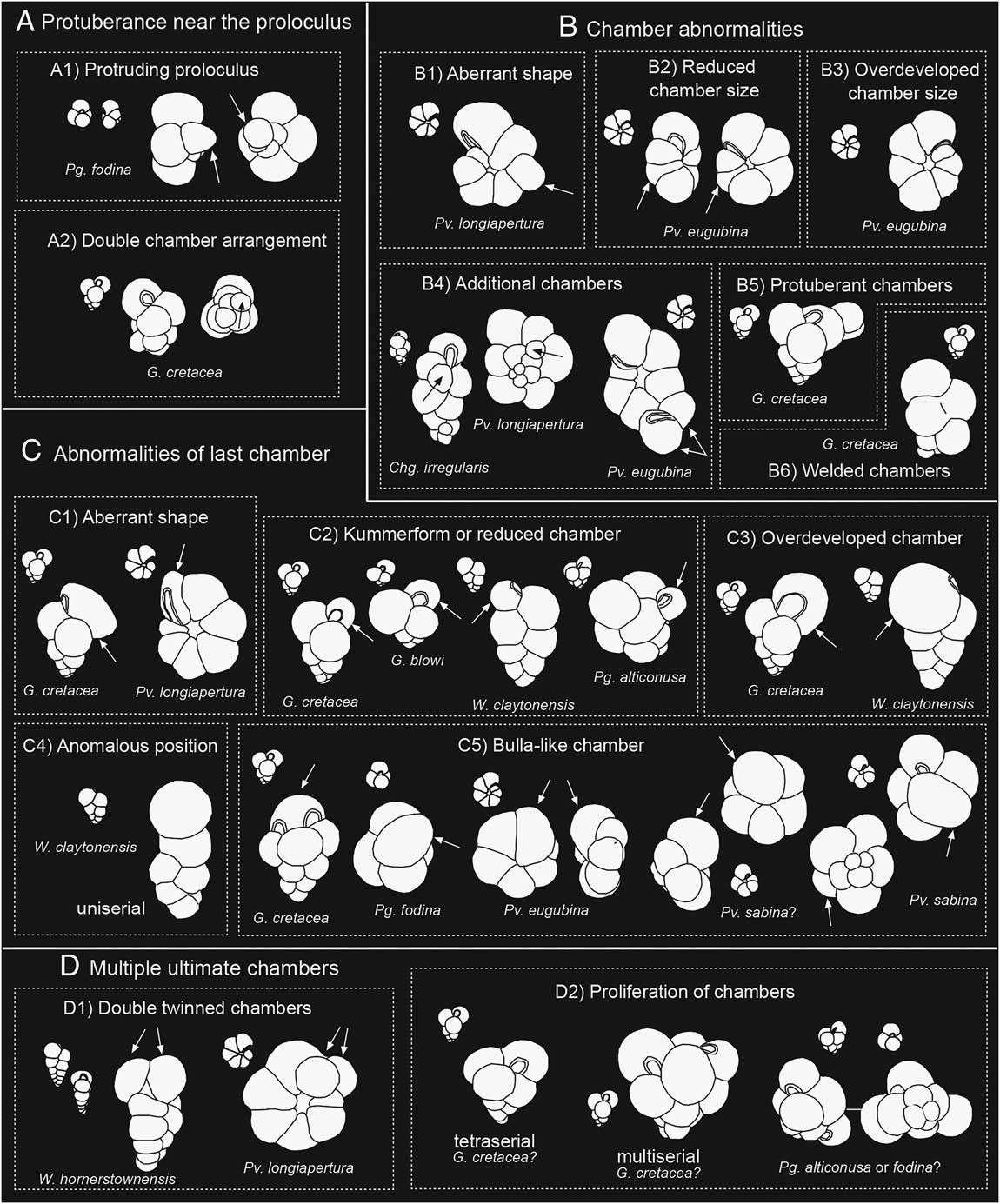

The terminology used here to describe the abnormalities identified in the earliest Danian (Figs. 4, 5) is based on those of Polovodova and Schönfeld (Reference Polovodova and Schönfeld2008), Ballent and Carignano (Reference Ballent and Carignano2008), and Montgomery (Reference Montgomery1990) for both benthic and planktic foraminifera. The specimens illustrated in Figures 6 and 7 and Supplementary Figures 5, 6, and 7 come mainly from El Kef and Aïn Settara, but also from Elles, Agost, and Caravaca. The aberrant morphologies identified belong to the following categories:

Figure 4 Schematic diagram of the main types of aberrant forms in the following categories: A, protuberances near the proloculus; B, chamber abnormalities; C, abnormalities of last chamber, including kummerforms; and D, multiple ultimate chambers, including double or twinned ultimate chambers (see explanation in text). Correlative normal forms are represented in miniature along with the abnormal forms.

Figure 5 Schematic diagram of the main types of aberrant forms in the following categories (continuing from Fig. 4): E, abnormal apertures, including multiple apertures; F, distortion in test coiling, including kinking; G, morphologically abnormal tests; H, double tests, including attached twins or fused tests; and I, general monstrosities (see explanation in text). Correlative normal forms are represented in miniature along with the abnormal forms.

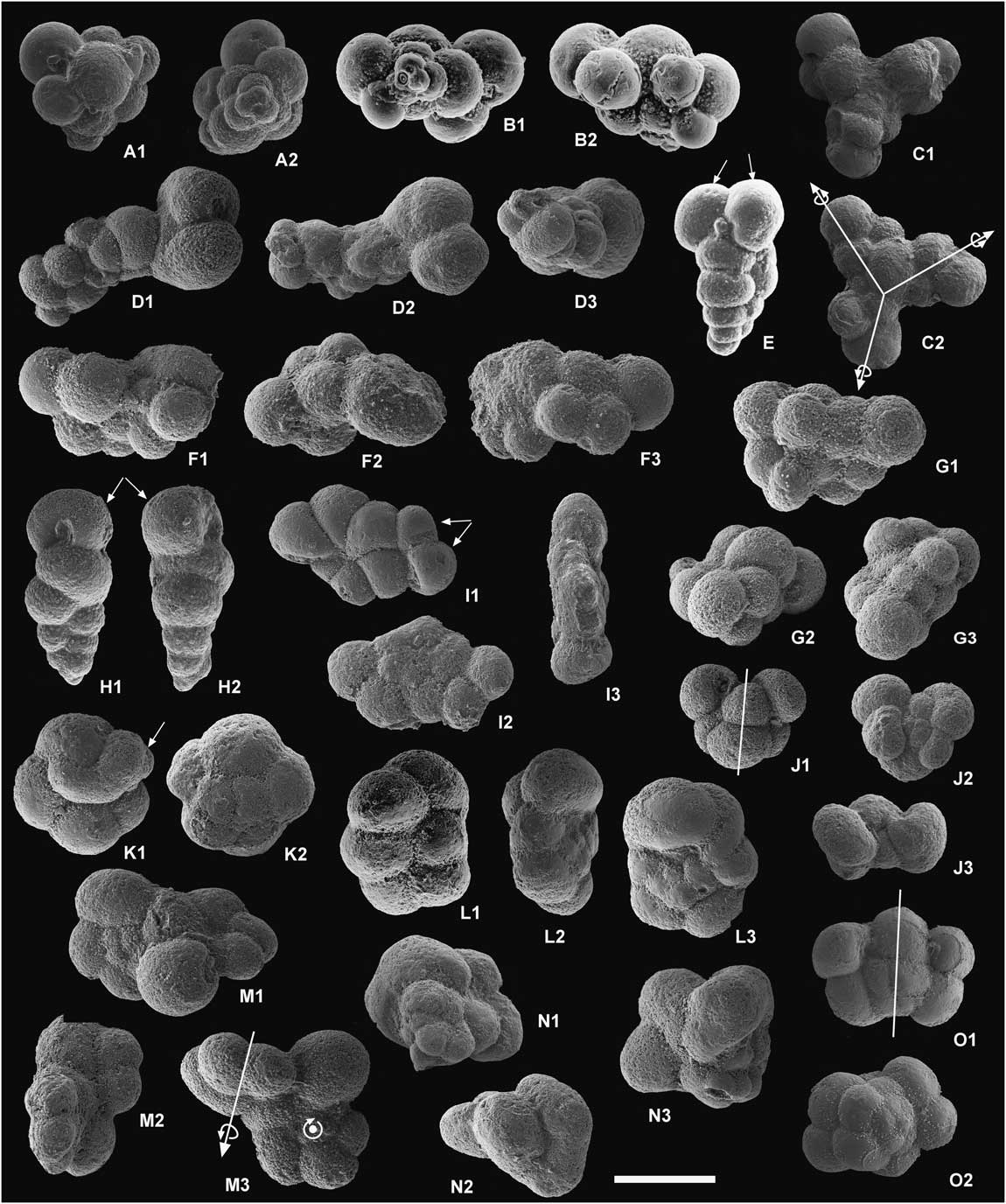

Figure 6 Examples of extreme aberrant forms of early Danian planktic foraminifera. Scale bar, 100 microns. A and B, Guembelitria spp., multiple ultimate chambers (racemiguembeliform multiserial test). C, Guembelitria sp. (probably G. cretacea), attached triplets (triamese). D, Guembelitria sp. or Woodringina sp., general monstrosity (probably attached twins with abnormal, kummerform, and protuberant chambers). E, W. hornerstownensis, double or twinned ultimate chambers. F, Guembelitria sp. or Woodringina sp., general monstrosity (probably attached twins with abnormal chambers). G, Parvularugoglobigerina sp. or Palaeoglobigerina sp., general monstrosity. H, W. hornerstownensis, last chamber in anomalous position, with test going from biserial to uniserial. I, Pv. longiapertura, additional chambers and apertures. J, Palaeoglobigerina sp. (probably Pg. luterbacheri), attached twins (Siamese). K, Pv. sabina, bulla-like ultimate chamber. L, Pv. eugubina, twisting of entire test (extreme kinking) and overdeveloped last chambers. M, Parvularugoglobigerina sp. (probably Pv. longiapertura), two specimens with fused tests. N, Palaeoglobigerina sp., general monstrosity. O, Parvularugoglobigerina sp.; additional chambers and apertures. All specimens come from El Kef, except for some from Aïn Settara (E, F).

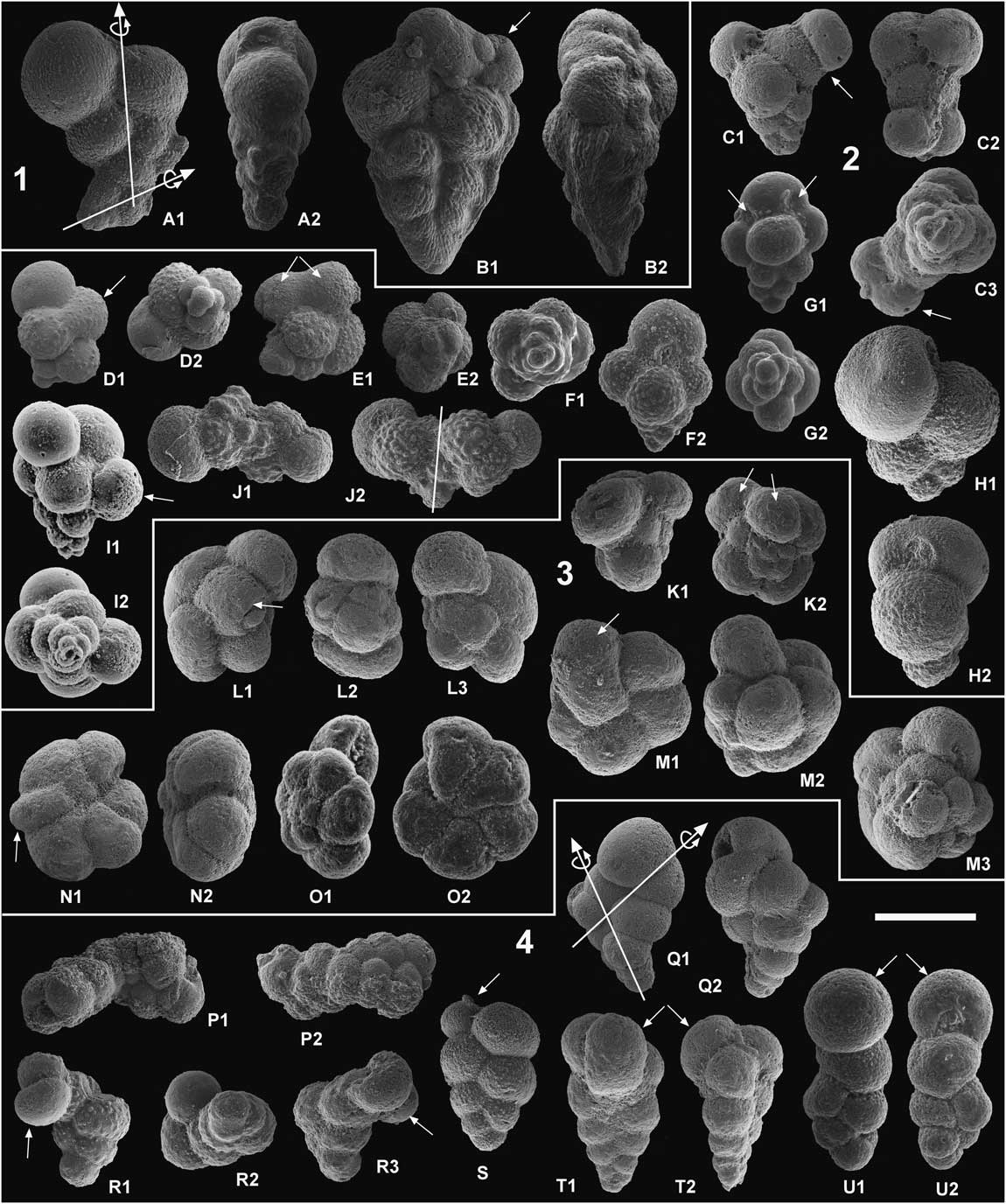

Figure 7 Examples of aberrant planktic foraminifera ordered by time intervals and environmental and evolutionary episodes. Scale bar, 100 microns. 1. Latest Maastrichtian: A, Heterohelix globulosa, kinking with change in the coiling direction. B, Pseudoguembelina kempensis, with multiple ultimate chambers. 2. PFAS-1 and transition between PFAS-1 and PFAS-2: C, Guembelitria sp. (probably G. cretacea), protuberant chambers. D and E, Guembelitria sp. (probably G. cretacea), welded chambers. F, Guembelitria sp. (probably G. cretacea), tetraserial form. G, Guembelitria sp. (probably G. cretacea), tetraserial form with multiple apertures. H, W. claytonensis, abnormal test with overdeveloped or inflated chambers. I, Guembelitria sp., multiple ultimate chambers (racemiguembeliform multiserial test). J, Chiloguembelitria sp. (probably Chg. trilobata), attached twins (Siamese). 3. PFAS-2: K, Pg. luterbacheri, double twinned chambers. L, Pv. sabina, bulla-like ultimate chamber. M, Parvularugoglobigerina sp., bulla-like ultimate chamber. N, Pv. eugubina, protuberant aberrant chamber. O, Pv. longiapertura, abnormally spiroconvex test. 4. Lower part of PFAS-3 (Chiloguembelitria acme): P, W. claytonensis?, general monstrosities, probably attached twins (Siamese) with abnormal chambers. Q, W. hornerstownensis, kinking with change in the coiling direction. R, W. claytonensis, kinking with change in the coiling direction and last chambers apparently protuberant. S, W. claytonensis, reduced last chamber (kummerform). T, Ch. taurica, last chamber in anomalous position, with test going from biserial to triserial. U, W. claytonensis, last chamber in anomalous position, with test going from biserial to uniserial. Most of the specimens come from El Kef, and the rest are from Aïn Settara (F, P, Q), Elles (G, K), Agost (O), and Caravaca (T).

1. Protuberance near the proloculus, which includes two types: (a) protruding proloculus (Fig. 4A1); and (b) second chamber abnormally protruding beside the proloculus (Fig. 4A2), also known as a double- or twinned-chamber arrangement. The latter occurs during the calcification of juvenile individuals and may be a result of frustrated double tests (Stouff et al. Reference Stouff, Debenay and Lesourd1999). During the early ontogenetic stage, two chambers can grow from the proloculus with subsequent development of an independent whorl from each of the second chambers; if a single whorl develops from one of these chambers, then the other appears as a protuberance on the proloculus (Polovodova and Schönfeld Reference Polovodova and Schönfeld2008).

2. Chamber abnormalities, which include six types: (a) aberrant shapes (Fig. 4B1); (b) reduced chamber sizes (Fig. 4B2); (c) overdeveloped chambers of the last whorl (Fig. 4B3); (d) additional chambers (Fig. 4B4); (e) protuberant chambers (Fig. 4B5); and (d) welded chambers (Fig. 4B6). Overdeveloped and reduced chambers have been related to environmental stress (Hecht and Savin Reference Hecht and Savin1972). For benthic foraminifera, Sujata et al. (Reference Sujata, Nigam, Saraswat and Linshy2011) proposed that abnormal chambers are a result of specimens being subjected to temporary hyposaline conditions, which causes considerable dissolution and the subsequent regeneration of the chamber in an abnormal form. The same phenomenon could be applied to planktic foraminifera in conditions of acidified waters with increased carbonate dissolution, as occur in global warming–hyperthermal episodes (e.g., Luciani et al. Reference Luciani, Giusberti, Agnini, Backman, Fornaciari and Rio2007).

3. Abnormal ultimate chamber, which includes five types: (a) aberrant shape (Fig. 4C1); (b) kummerform, or reduced last chamber (Fig. 4C2); (c) overdeveloped or inflated last chamber (Fig. 4C3); (d) anomalous position (Fig. 4C4) causing, for example, the change from biserial/triserial to uniserial; and (e) bulla-like chamber (Fig. 4C5), that is, the last chamber partially or totally covering the umbilicus, resembling a bulla. The first three types are identified here in all the planktic foraminiferal groups and are frequently associated with a decrease in ornamentation. The bulla-like last chamber is typical of high trochospiral specimens with an intraumbilical or quasi-intraumbilical aperture, as in some species of Palaeoglobigerina and Parvularugoglobigerina. Hecht and Savin (Reference Hecht and Savin1972) reported that bulla-like abnormal chambers are more common in warmer waters and seem to develop on unusually long-lived specimens (Montgomery Reference Montgomery1990). According to Bijma et al. (Reference Bijma, Hemleben, Oberhänsli and Spindler1992), abnormal last chambers could be induced by the ocean oxygen level, light quality, or feeding rate. Saclike overdeveloped chambers seem currently to be more common in upwelling areas characterized by waters that are more anoxic and richer in nutrients and in more yellow-green light conditions. Kummerform chambers are probably the result of the opposite conditions, that is, more oxygenated waters, oligotrophy, and light conditions (blue) typical of the open ocean.

4. Multiple ultimate chambers, which include two types: (a) double or twinned ultimate chambers (Fig. 4D1); and (b) proliferation of chambers in the last whorl(s) (Fig. 4D2). They are present mostly in triserial species (Guembelitria), but are also found here in the trochospiral Palaeoglobigerina. In Guembelitria, these additional chambers are usually disposed in several directions (multiserial forms). Many triserial specimens exhibit an ultimate tetraserial stage and have probably been misidentified as Palaeoglobigerina alticonusa and/or Trochoguembelitria alabamensis (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Others, mainly biserials, have two complete and identical ultimate chambers. According to Venturati (Reference Venturati2006), twinned or bilobated chambers may be used as potential proxies for environmental stress. Montgomery (Reference Montgomery1990) suggested that specimens with multiple last chambers could also be some type of gerontic kummerforms, because these chambers tend to be downsized and similar in shape, and this could indicate long life.

5. Abnormal apertures, which include three types: (a) aberrant shape (e.g., gaping aperture), usually associated with abnormal ultimate chambers (Fig. 5E1); (b) additional aperture (Fig. 5E2); and (c) multiple apertures (Fig. 5E3), usually associated with multiple ultimate chambers. According to Montgomery (Reference Montgomery1990), gaping apertures represent a strategy directly opposed to that of apertures covered by bullae, whose function is to protect them.

6. Distortion in test coiling, which includes three types: (a) excessively high spiral side or spiroconvex test (Fig. 5F1); (b) kinking (Fig. 5F2), that is, abnormal coiling due to a change in the direction of coiling, with two or more axes of rotation; and (c) twisting of entire test or extreme kinking (Fig. 5F3), that is, the umbilical side becomes the spiral side. Distortion in test coiling also seems to be a response to very stressed environments (Montogomery 1990; Polovodova and Schönfeld Reference Polovodova and Schönfeld2008).

7. Abnormal test, which includes four types: (a) lack of sculpture (Fig. 5G1); (b) poor development of the last whorl (Fig. 5G2); (c) overdevelopment of the last whorl (Fig. 5G3); and (d) compressed test (Fig. 5G4). Another test abnormality is a lack of ornamentation, but this type is not been analyzed here due to the difficulty of demonstrating the difference between abnormal alterations in the wall surface and the diagenetic processes of dissolution/recrystallization, which are usual in El Kef and Aïn Settara. As in the previous category, these abnormalities also seem to be a response to stressed environments (Polovodova and Schönfeld Reference Polovodova and Schönfeld2008), in some cases due to extremely stressful shifts in the environment (Montgomery Reference Montgomery1990).

8. Attached twins or double tests, which include two types: (a) attached twins (Siamese) (Fig. 5H1), or even attached triplets (triamese) (Fig. 6.C); and (b) fused test (Fig. 5H2). If a second chamber beside the proloculus is followed by the development of an adjacent whorl, with two whorls with a similar number of chambers developing synchronously, attached twins are formed. Stouff et al. (Reference Stouff, Debenay and Lesourd1999) proposed that double tests in benthic foraminifera may result from: (i) an anomaly in the development of a single juvenile, building two or three second chambers or two third chambers, each one possibly developing in an individual whorl; (ii) the early fusion of two juveniles, which both develop after their fusion; (iii) the attachment of a juvenile to a parental test after schizogony, followed by the development of the juvenile specimen. According to Montgomery (Reference Montgomery1990), twinned specimens indicate reproductive difficulties in stressed environments.

9. General monstrosities (Fig. 5I): a conjunction of abnormal coiling due to several wrong directions of coiling, bulla-like kummerform chambers, double tests, and multiple ultimate chambers can generate monstrous abnormalities. Montgomery (Reference Montgomery1990) proposed that monstrosities are probably crushed and repaired specimens resulting from extremely stressful shifts in their environment or increased predation by organisms such as copepods.

Paleoenvironmental and Evolutionary Implications

Uppermost Maastrichtian Evolutionary Stability in Open-Ocean Assemblages

According to Keller et al. (Reference Keller, Bhowmick, Upadhyay, Dave, Reddy, Jaiprakash and Adatte2011), Font et al. (Reference Font, Adatte, Sial, de Lacerda, Keller and Punekar2016), and Punekar et al. (Reference Punekar, Keller, Khozyem, Adatte, Font and Spangnberg2016), the main eruptive phase (phase 2) of the Deccan Traps may have been concentrated during the last ~50 or 100 Kyr of the Maastrichtian, triggering a short episode of global cooling—and ocean acidification—as a result of sulfate aerosol particles injected into the stratosphere and increased levels of mercury, an extremely toxic heavy metal. Opportunistic Guembelitria blooms have also been identified in the uppermost Maastrichtian, mainly in the shallow-marine environments of Israel, Egypt, Texas, and India, which suggests that the environmental deterioration and extinction began with the Deccan eruptions, several tens of thousands of years before the K/Pg boundary (Punekar et al. Reference Punekar, Mateo and Keller2014; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Mateo and Punekar2016). However, only minor Guembelitria blooms are present in the deep-marine environments of the Maastrichtian (Pardo and Keller Reference Pardo and Keller2008; Punekar et al. Reference Punekar, Mateo and Keller2014). As proposed for warming episodes in the early Danian, Guembelitria acmes in shallow neritic environments could have also been under an orbital control related with small variations in sea level, temperature, acidity, and nutrients due to Milankovitch cycles (Quillévéré et al. Reference Quillévéré, Norris, Kroon and Wilson2008; Coccioni et al. Reference Coccioni, Frontalini, Bancalà, Fornaciari, Jovane and Sprovieri2010).

To test the hypothesis that the main eruptive phase (phase 2) of the Deccan Traps may have been concentrated during the last ~50 or 100 Kyr of the Maastrichtian, we have for the first time appraised the rate of aberrant planktic foraminifera in the upper part of the P. hantkeninoides Subzone from El Kef and Aïn Settara, as a proxy for ecological stress episodes. Our results indicate that there was a low frequency of aberrants (generally <2.5%) across this interval (Tables 1, 2), similar to the levels recorded in recent deep-ocean sediments under “normal” environmental conditions and reflecting the natural background number of malformations among planktic foraminifers (Mancin and Darling Reference Mancin and Darling2015). Low extinction and speciation rates, as well as low volatility and taxonomic flux fluctuations (Figs. 2 and 8), corroborate the high evolutionary stability that prevailed during the latest Maastrichtian in El Kef.

Figure 8 Shifts in specific richness (species number), speciation rate and volatility (according to the model of Dean and McKinney, Reference Dean and McKinney2001), relative abundance (%) of triserial specimens, and FAI (rate of aberrants in %) across the K/Pg boundary at El Kef; solid line and gray shading: hypothesis of pattern A; dotted line and black shading: hypothesis of pattern B; orange shading: terminal stress levels according to the model of Weinkauf et al. (Reference Weinkauf, Moller, Koch and Kucera2014), A corresponding to PFAS-1 and B to the Chiloguembelitria acme; green shading, evolutionary radiations, with shading in dark green to indicate high speciation rates (see online version for color). FAI, Foraminiferal Abnormality Index (% aberrant planktic foraminifera). *Mh. holmdelensis Subzone (= Zone P0); **Pv. longiapertura Subzone.

Proliferation of Aberrant Planktic Foraminifera, Chemical Pollution, and Global Warming during the Earliest Danian

The causes proposed to explain the abnormalities in planktic foraminiferal tests are still very vague, including biological factors (such as unusually high levels of intraspecific variability) or various chemical and physical stressors (see Mancin and Darling Reference Mancin and Darling2015). For example, Coccioni and Luciani (Reference Coccioni and Luciani2006) speculated that blooms of aberrant G. irregularis across the K/Pg boundary are explained as the result of rapid and extreme fluctuations in climate and sea level, as well as intense volcanism and meteoritic impact events, which could have stressed surface waters. The higher values in the FAI identified here during the first 200 Kyr of the Danian (affecting not only G. irregularis but all the planktic foraminiferal groups), however, require a better understanding of how the long-term effects of the Chicxulub impact or the paleoenvironmental changes induced by the Deccan eruptions affected planktic foraminiferal assemblages during the early Danian.

Model calculations have suggested several short-term (hour- to decade-long) environmental perturbations caused by the Chicxulub impact (see reviews in Kring Reference Kring2007; Schulte et al. Reference Schulte, Alegret, Arenillas, Arz, Barton, Bown, Bralower, Christeson, Claeys, Cockell, Collins, Deutsch, Goldin, Goto, Grajales-Nishimura, Grieve, Gulick, Johnson, Kiessling, Koeberl, Kring, MacLeod, Matsui, Melosh, Montanari, Morgan, Neal, Nichols, Norris, Pierazzo, Ravizza, Rebolledo-Vieyra, Reimold, Robin, Salge, Speijer, Sweet, Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Vajda, Whalen and Willumsen2010; Brugger et al. Reference Brugger, Feulner and Petri2017; Artemieva et al. Reference Artemieva and Morgan2017). These include a global pulse of increased thermal radiation on the ground and wildfires caused by the atmospheric re-entry of the ejecta spherules, the production of acid rain, and an injection of dust and aerosol particles into the atmosphere, blocking the sunlight. Using TEX86 paleothermometry, a short-term cooling (or “impact winter” phase) during the first months to decades following the Chicxulub impact has been documented at the Brazos River section in Texas (Vellekoop et al. Reference Vellekoop, Sluijs, Smit, Schouten, Weijers, Damsté and Brinkhuis2014). Short-term global perturbations were likely major lethal factors for planktic foraminifera in the K/Pg mass extinction event (lasting months or a few years), but are insufficient to account for the increase of aberrants identified in the first 200 Kyr of the Danian.

Increased teratological forms in recent foraminifera are usually related with highly polluted areas (e.g., Alve Reference Alve1991; Yanko et al. Reference Yanko, Ahmad and Kaminski1998; Geslin et al. Reference Geslin, Debenay, Duleba and Bonetti2002; Martin and Nesbitt Reference Martin and Nesbitt2015). Under the effect of extreme poisoning by heavy metals, the ability of foraminifera to constrain the shape of their shells is limited, leading to aberrant morphologies (Caron et al. Reference Caron, Faber and Bé1987). The action of toxic heavy metals must have been very intense immediately after the Chicxulub impact. According to Erickson and Dickson (Reference Erickson and Dickson1987), a hypothetical 10-km-diameter chondritic impactor such as that of Chicxulub contains a mass of heavy metals, such as cobalt, nickel, copper, and mercury, comparable to or larger than the world ocean burden. Several heavy metals have relatively inefficient removal mechanisms, such as copper and nickel with greater than 1000-yr steady-state oceanic residence times. In addition, the worldwide sediments contaminated with heavy metals from the Chicxulub impact site may well have been eroded, removed, and resuspended in oceans for several thousand years (Smit and Romein Reference Smit and Romein1985; Smit et al. Reference Smit, Roep, Alvarez, Montanari, Claeys, Grajales-Nishimura and Bermudez1996). Premovic et al. (Reference Premovic, Todorovic and Stankovic2008) suggested that humics enriched in heavy metals were transported mainly by fluvial means into the ocean and deposited in the dark-clay bed. Enhanced levels of toxic heavy metals (e.g., nickel, zinc, chromium, cobalt, or copper) have been identified in the dark-clay bed, that is, in the first 10 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary, at Caravaca (Smit and ten Kate Reference Smit and ten Kate1982), Aïn Settara (Dupuis et al. Reference Dupuis, Steurbaut, Molina, Rauscher, Tribovillard, Arenillas, Arz, Robaszynski, Caron, Robin, Rocchia and Lefèvre2001), and Stevns Klint, Denmark (Premovic et al. Reference Premovic, Todorovic and Stankovic2008).

Chicxulub impact–linked chemical pollution could therefore be a major cause of the first bloom of aberrant planktic foraminifers within the dark-clay bed. In addition, the large amount of CO2 gas devolatilized in the Chicxulub impact and the collapse of ocean productivity and the biological pump initiated intense global warming through the greenhouse effect after the post-impact winter phase (Kawaragi et al. Reference Kawaragi, Sekine, Kadono, Sugita, Ohno, Ishibashi, Kurosawa, Matsui and Ikeda2009), persisting as another ecological stress factor for thousands of years. Isotopic data from El Kef indicate a sudden negative excursion in bulk-sediment δ13C and δ18O after the K/Pg boundary (Keller and Lindinger Reference Keller and Lindinger1989), suggesting a warming episode and a decrease in biological productivity at the time of the dark-clay bed deposition and PFAS-1. According to the GTS12 and the biochronological scale of Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz and Molina2004), this negative δ13C excursion lasted for the first 20–25 Kyr of the Danian.

Another potential cause of the first peak of aberrant planktic foraminifers in PFAS-1 could be phytoplankton blooms concentrating toxins in the surface waters (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Bralower, Patzkowsky, Kump and Schueth2010; Schueth et al. Reference Schueth, Bralower, Jiang and Patzkowsky2015). Toxicity is a well-known product of modern plankton blooms (Castle and Rodgers Reference Castle and Rodgers2009), and geographically heterogeneous spikes of phytoplankton groups are reported in the earliest Danian. For example, quantitative analyses with organic-walled marine dinoflagellate cyst assemblages in the lowermost Danian of El Kef show a relevant acme of the Andalusiella–Palaeocystodinium complex between 10 and 15 cm above the K/Pg boundary (Brinkhuis et al. Reference Brinkhuis, Bujak, Smit, Versteegh and Visscher1998). This peak correlates approximately with the initial increase in aberrant tests of planktic foraminifera at El Kef, but not with the maximum values recorded between 37 and 97 cm above the K/Pg boundary (Fig. 3, Table 1). Although phytoplankton blooms may have favored the concentration of toxins in the surface-water layers, more studies are needed to establish the relationship between such blooms and the proliferations of aberrant planktic foraminiferal tests in the early Danian. In any case, spikes of Andalusiella–Palaeocystodinium complex and other groups (such as the calcareous dinoflagellate cyst Thoracosphaera spp. or the nannofossil species Braarudosphaera bigelowii) identified in the Tethyan realm are usually explained as blooms of opportunistic taxa related to long-term environmental effects of the Chicxulub impact (Lamolda et al. Reference Lamolda, Melinte and Kaiho2005; Vellekoop et al. Reference Vellekoop, Smit, van de Schootbrugge, Weijers, Galeotti, Sinninghe Damsté and Brinkhuis2015).

On the basis of several independent stratigraphic, geochronological, geochemical, and tectonic constraints, Richards et al. (Reference Richards, Alvarez, Self, Karlstrom, Renne, Manga, Sprain, Smit, Vanderkluysen and Gibson2015) hypothesized that the main Deccan eruptive phase (phase 2, >70% of the lava flows) could have been triggered by the Chicxulub impact during a relatively brief time interval on the order of one to several hundred thousand years. If this hypothesis by Richards et al. (Reference Richards, Alvarez, Self, Karlstrom, Renne, Manga, Sprain, Smit, Vanderkluysen and Gibson2015) is correct, the long-term disruptive effects of the Chicxulub impact could be combined in the early Danian with those of Deccan volcanism, including a chemical contamination of the ocean surface over a longer period of time. This hypothesis could explain why the values of the FAI at the El Kef and Aïn Settara sections remained high during at least the first 200 Kyr after the Chicxulub impact (including the interval PFAS-2).

As mentioned earlier, the second increase in aberrant forms coincides with the Chiloguembelitria bloom in the lower part of PFAS-3 (Figs. 3, 8). This episode spanned between approximately 70 and 200 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary, so it cannot be related to the long-term disruptive effects of the Chicxulub impact. On the contrary, it seems that it was caused by another independent, later period of intense ecological stress perhaps linked to the Deccan eruptions (phase 2 or 3). Quillévéré et al. (Reference Quillévéré, Norris, Kroon and Wilson2008) recognized in the lower Danian (in the E. trivialis Subzone, or Subzone P1a) a warming episode called Dan-C2 (the first hyperthermal episode of the Paleogene), which lasted approximately 100 Kyr. Although Dan-C2 and similar episodes could be a result of orbital cycles, Coccioni et al. (Reference Coccioni, Frontalini, Bancalà, Fornaciari, Jovane and Sprovieri2010) proposed a possible link between this warming episode and the Deccan volcanism. According to this scenario, the second increase of the FAI, the Chiloguembelitria bloom, and the Dan-C2 episode could therefore be related. The low values of the FAI after the Chiloguembelitria bloom (in the S. triloculinoides Subzone, or Subzone P1b) suggest a period of greater environmental stability. This interval is widely dominated by biserial Woodringina and Chiloguembelina, typical of the PFAS-3 episode. Nevertheless, Coccioni et al. (Reference Coccioni, Frontalini, Bancalà, Fornaciari, Jovane and Sprovieri2010) suggested that the predominance of biserials in Gubbio, along with other micropaleontological and geochemical proxies, was indicative of stressed ecological conditions (climatic warming and low oxygenation and acidification of ocean waters) during the Dan-C2 episode. According to this scenario, the whole PFAS-3 episode could be a record of the late eruptions of Deccan phase 2 or the first eruptions of phase 3. Moreover, the Chiloguembelitria bloom in the lower part of PFAS-3 could be the result of a more intense volcanic pulse during Dan-C2, though not one recorded at Gubbio by Coccioni et al. (Reference Coccioni, Frontalini, Bancalà, Fornaciari, Jovane and Sprovieri2010).

Evolutionary Implications

Weinkauf et al. (Reference Weinkauf, Moller, Koch and Kucera2014) suggested that the phenotypic history of planktic foraminiferal assemblages allows the detection of threshold levels of ecological stress episodes that are likely to lead to extinction. According to these authors, an increase in interspecific morphological variability and abnormal forms can be observed at terminal stress levels immediately before extinction, indicating disruptive selection. In contrast, in periods of environmental stability and nonterminal stress levels, a decrease in morphological variability and abnormal forms is recognized, indicating stabilizing selection.

If the hypothesis that the massive eruptions of Deccan phase 2 were concentrated in the last 50 or 100 Kyr of the Maastrichtian and started a gradual mass extinction in planktic foraminifera before the K/Pg boundary (Punekar et al. Reference Punekar, Keller, Khozyem, Adatte, Font and Spangnberg2016) is correct, a terminal stress episode with abundant aberrant forms should have been recorded below the K/Pg extinction horizon at El Kef and Aïn Settara. However, there is no evidence for such a scenario and, as in many sections worldwide, most Maastrichtian species suddenly become extinct at the K/Pg boundary following a catastrophic extinction pattern compatible with the short-term effects of the Chicxulub impact (Smit Reference Smit1982, Reference Smit1990; Huber Reference Huber1996; Arz et al. Reference Arz, Arenillas, Molina and Sepúlveda2000; Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuis2000a,Reference Arenillas, Arz, Molina and Dupuisb; Huber et al. Reference Huber, MacLeod and Norris2002; Molina et al. Reference Molina, Alegret, Arenillas and Arz2005; Gallala Reference Gallala2014). Similarly, latest Maastrichtian climatic fluctuations and environmental perturbations linked to Deccan volcanism had a relatively weak impact on the diversity of the calcareous nannoplankton assemblages before the K/Pg boundary, as evidenced in Elles and other sections worldwide (Thibault et al. Reference Thibault, Galbrum, Gardin, Minoletti and Le Callonnec2016).

The first bloom of aberrants and PFAS-1 in the earliest Danian occurred in an interval in which the speciation rate was very high, especially in the lower part of the Pv. longiapertura Subzone, which also shows high volatility and relevant fluctuations in the taxonomic flux (Figs. 2 and 8). Arenillas et al. (Reference Arenillas, Arz, Grajales-Nishimura, Meléndez and Rojas-Consuegra2016) suggested that the speciation rate may have been increased in response to the long-term meteoritic pollution of the oceans, which may have caused increased mutation rates for at least 10 to 20 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary and triggered the first evolutionary radiation of planktic foraminifera. Many mutations in planktic foraminifera are likely to have been lethal, causing mortality before the adult stage was reached. However, genetic mutations could have accelerated the evolution of planktic foraminifera in the early Danian, being amplified as a consequence of stressed and adverse environments (BouDagher-Fadel Reference BouDagher-Fadel2012). In addition, many other mutations would have been deleterious, producing malformations and teratological forms, as has been proposed for recent foraminifera (e.g., Mancin and Darling Reference Mancin and Darling2015). The high values of the FAI identified in the dark-clay bed and PFAS-1 at El Kef and Aïn Settara are consistent with this hypothesis. This interval occurred during the survival and recovery phases after the K/Pg boundary extinction according to the terminology of Kauffman and Erwin (Reference Kauffman and Erwin1995), in which Guembelitria included the “disaster species” and the minute parvularugoglobigerinids the “progenitor species” (Molina Reference Molina2015), although the latter had a benthic origin, as has recently been proposed by Arenillas and Arz (Reference Arenillas and Arz2017). The evolutionary history of the planktic foraminifera was restarted almost from scratch after the K/Pg boundary extinction, suggesting that all the latest Maastrichtian species went extinct at the K/Pg boundary, except for some species of Guembelitria (see also Smit Reference Smit1982; Arenillas et al. Reference Arenillas, Arz, Grajales-Nishimura, Meléndez and Rojas-Consuegra2016).

The second bloom of aberrants and the Chiloguembelitria acme appear to be better adjusted to a terminal stress episode, as proposed by Weinkauf et al. (Reference Weinkauf, Moller, Koch and Kucera2014). Nonterminal stress episodes could correspond to PFAS-2, dominated by parvularugoglobigerinids and characterized by an aberrant rate lower than in PFAS-1 and the Chiloguembelitria acme. It is not possible to speak of environmental stability in PFAS-2, because values of the FAI and volatility remain high. In fact, the speciation rate in the upper part of PFAS-2 is high (Fig. 8) as a consequence of the beginning of the second evolutionary radiation. Nevertheless, the maximum in species richness (S=species number) of the early Danian is reached during the beginning of the Chiloguembelitria acme (Fig. 8), which represents a terminal stress episode. This is because the species that emerged during the first and second evolutionary radiations overlapped in time (Fig. 1). The parvularugoglobigerinids, which appeared in the first radiation, went extinct toward the end of the Chiloguembelitria acme, increasing the extinction rate (Fig. 8). Parvularugoglobigerinids were replaced definitively by the more ornamented, larger trochospiral species of the second evolutionary radiation. In this case, the Chiloguembelitria included the disaster species, and the species that appeared in the second radiation (those of Eoglobigerina, Parasubbotina, Globanomalina, and Praemurica, among others) were the progenitor species.

Conclusions

1. A high-resolution, quantitative biostratigraphic study across the K/Pg boundary from open-ocean Tunisian sections (El Kef and Aïn Settara) revealed a proliferation of aberrant planktic foraminifera during approximately the first 200 Kyr of the Danian. Various categories and types of abnormalities were identified, including abnormal tests, extra chambers, attached twin tests, and general monstrosities.

2. The proliferation of aberrants occurred in two main pulses. The first was more intense and occurred during the first 20 to 25 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary, spanning the dark-clay bed. It is characterized by abnormal forms of triserials (Guembelitria), but also of parvularugoglobigerinids (Parvularugoglobigerina and Palaeoglobigerina) from just the first evolutionary radiation of Danian planktic foraminifera. The second pulse is recorded between approximately 70 and 200 Kyr after the K/Pg boundary and is characterized mainly by abnormal forms of triserials (Chiloguembelitria) and biserials (Woodringina and Chiloguembelina).

3. These two pulses of aberrants correlate respectively with the Guembelitria acme in PFAS-1 and the dark-clay bed and with the Chiloguembelitria acme in the lower part of PFAS-3, both of which have been interpreted as ecological stress episodes. The FAI during the parvularugoglobigerinid acme in PFAS-2 is lower, but remains high enough to suggest that environmental conditions were also unstable during this interval, in which the second evolutionary radiation of Danian planktic foraminifera occurred.

4. According to the data set available here, the high values of the FAI in PFAS-1 seems to be more related to long-term environmental effects of the Chicxulub impact. By contrast, the second bloom of aberrants during the Chiloguembelitria acme was caused by an independent, later period of ecological stress perhaps linked to the Deccan eruptions.

5. The absence of an ecological stress episode rich in abnormal tests during the latest Maastrichtian in both the El Kef and Aïn Settara locations, as well as the high values of the FAI during the first 200 Kyr of the Danian, could be compatible with the hypothesis that the Chicxulub impact triggered the main phase of the Deccan Traps. This would render the Deccan volcanism an unlikely candidate as the cause of the K/Pg boundary mass extinction.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Polovodova, C. M. Lowery, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and critiques, which have greatly helped improve this paper. This study is a contribution to project CGL2015-64422-P (MINECO/FEDER-UE) and is also partially supported by the Departamento de Educación y Ciencia of the Aragonian Government, cofinanced by the European Social Fund (grant number DGA group E05). V.G. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (FPI grant BES-2016-077800). The authors would like to acknowledge the use of the Servicio General de Apoyo a la Investigación-SAI, Universidad de Zaragoza. The authors are grateful to Rupert Glasgow for improvement of the English text.

Supplementary Material

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.n1q6527