ALL THE WORLD’S A STAGE;

A GEOLOGICAL PARODY.

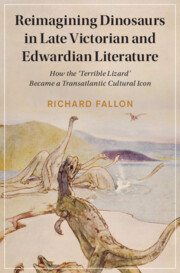

In 1889, the Reverend Henry Neville Hutchinson (1856–1927) twisted Jaques’s famous lines from Shakespeare’s As You Like It into a narrative of evolutionary progress. This contribution to Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip marked the start of a prolific writing career in the popularisation of archaeology, anthropology, geology, and especially palaeontology (Figure 1.1). The leading popular writer on palaeontology in Britain and the United States during the 1890s, and a well-known author on this subject until the 1920s, Hutchinson shaped public conceptions of the prehistoric world – and dinosaurs above all – for several critical decades. Meanwhile, as his Shakespearean parody suggests, he also espoused the cause of imaginative literature. Hutchinson’s passion for all things literary infused his scientific books with allusions to poets and authors of fiction ranging from Homer to H. G. Wells. He even proposed, both in 1899 and in 1925, the creation of a beneficent British Association for the Advancement of Literature intended to mirror the functions of the venerable British Association for the Advancement of Science (founded 1831).2

Figure 1.1 Henry Neville Hutchinson’s carte de visite. The photograph was taken in 1884, when he was twenty-eight years old.

As implied by the parallel between these two British Associations, literary proclivities fed into Hutchinson’s ideals of science. He believed that the specialised technical language of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century science writing, along with its overly secular grounding, had alienated the general public. This alienation could be reversed by more captivating or romantic presentations of science, drawing upon fiction, poetry, and faith. He characteristically argued, for instance, that the audiences flocking to Shakespeare productions would equally enjoy skilfully delivered natural history lectures.3 Educated to see science, like Shakespeare, as a vibrant cultural force, Hutchinson hoped to popularise scientific information and encourage wider participation through books intended to be as readable as novels and by writing in the latest journalistic genres. This agenda led Hutchinson to criticise the accessibility of the oldest scientific societies, as well as the form and even accuracy of technical writing. His disparagement of the specialisation of knowledge and pronouncements on technical matters met with resistance. While Hutchinson was a fellow of various prestigious societies, including the Geological Society, he had little to no primary research to his name and held no institutional scientific positions. For certain savants, the superficially learned nature of Hutchinson’s popular books problematically challenged the hierarchies of knowledge within, and around the perimeter of, the elite scientific community.

The overlap between Hutchinson’s prominence in the popularisation of dinosaurs and his vision for the relationship between literature and science makes him a key subject in this book. Indeed, even in my later chapters, it will be seen that he is rarely far away. In this chapter I argue that, in opposition to Hutchinson’s participatory rhetoric, leading researchers characterised his palaeontology texts as literary patchworks and irrelevant to scientific thought. As Harry Govier Seeley (1839–1909) asserted in 1894, Hutchinson was writing ‘literature rather than science’.4 Furthermore, I demonstrate that these disagreements over the literary form of science writing held important implications for the public face of dinosaur palaeontology. As dinosaurs were the focus of Hutchinson’s most widely read books, the ambiguous authority of the author posed a threat to Seeley in particular. After all, Hutchinson was promoting the dinosaur classification scheme devised by an American, O. C. Marsh, which contradicted the British Seeley’s characterisation of the Dinosauria as an unnatural category. Around the turn of the century, the previously obscure term ‘dinosaur’ was gaining wider popularity, in no small part owing to Hutchinson’s books, with minimal recognition of Seeley’s objection that it was taxonomically unsound. By placing Hutchinson’s writings in a realm removed from truly scientific writing, Seeley policed the bounds of knowledge-making and attempted to delegitimise rival interpretations of these extinct animals.

Seeley’s characterisation of Hutchinson’s books as unscientific was reinforced by other men of science who criticised the register of ‘romance’ with which Hutchinson appealed to the public. Even during the Great War, when the word ‘dinosaur’ had become a meaningful term well beyond the palaeontological community, Hutchinson’s attempt to take part in an international debate over the anatomy of the famous American Diplodocus was complicated by his refusal or inability to adhere to the standards of the technical Geological Magazine. Critical attention has previously been paid to Hutchinson’s literary techniques, and his habit of provoking the ire of scientific researchers.5 The clashes discussed below, however, have yet to be explored. I contend that they are integral to our understanding of construction of the dinosaur and of the negotiation of boundaries between literary and scientific culture during an important transitional period. These encounters typify the interactions with which this book will be concerned: the tangle of populist publications, specialist disputes, and transatlantic exchanges from which a modern understanding of dinosaurs was fashioned.

A New Language

Hutchinson’s preferred fields, geology and palaeontology, have come to represent the nineteenth-century literary heights of science in Britain. Ralph O’Connor and Adelene Buckland, alongside many other scholars, have shown how pioneering writers and researchers like William Buckland and Charles Lyell built up the prestige and texture of geoscience through their romanticism, poetry, and finely honed prose about deep time and prehistoric monsters.6 Generically speaking, the works of these leading scientific researchers shaded imperceptibly into those of the many non-specialist journalists, novelists, and poets who also found the subject pregnant with suggestion. Geology and palaeontology thus occasioned a fertile interchange of concepts and aesthetic values. This was no homogenous culture in which literature and science were one indivisible category, but the boundaries of appropriate form and content among poetry and fiction, original scientific contributions, and works of popularisation were frequently contested and not necessarily self-evident.

As the nineteenth century progressed, however, clashes of authority between groups espousing different approaches to knowledge-making altered the forms of science writing and reorganised its readerships.7 In the latter half of the century, scientific contributions were increasingly published as technical articles in specialist journals, while writing for general audiences largely came to be called popularisation, often written by knowledgeable non-specialist journalists.8 These changes brought with them a corresponding bifurcation in literary style in which lavish figurative language and imaginative genres like poetry and fiction were being detached from any association with functional scientific contributions. Contemporaries were likely to consider the former firmly ‘literary’ writings and the latter ‘scientific’, categories which were recognised as being generally discrete, although non-fiction science for general readers maintained an uneasy position between these two poles.9 Even if, as I have detailed in the Introduction, scholars now look beyond these categories, their utility became a matter of little doubt to most contemporaries.

At the fin de siècle, the technical language and sheer quantity of disciplinary research continued to erode what were seen as the general readerships for scientific contributions, even in the previously fashionable earth sciences. Thomas George Bonney, formerly Hutchinson’s geology tutor at Cambridge, remarked upon this development in 1893:

Forty years since, a book dealing with the main principles of geology, such as Sir C. Lyell’s well-known work [Principles of Geology (1830–3)], would have been understood with little difficulty by any man of good general education: two pages of print would have contained all the technical terms which had to be mastered. But these have now become so numerous that the beginner has not only to comprehend new ideas, but also to learn a new language.10

Lyell’s Principles of Geology was widely read in the 1830s, coupling grandiose visions of deep time with an exciting argument for the consistent rate of geological processes. James A. Secord has dubbed books like Principles, which addressed general readers while also making a critical specialist contribution, ‘reflective treatises’. These treatises, which are to be considered distinct from works of overt popularisation, were at their most widespread in the 1830s, although they continued to be published throughout the century, most notably by Charles Darwin.11 At the end of the century, however, the genre was seemingly wavering. Peter J. Bowler finds something similar, the ‘serious nonspecialist’ book, to have occupied a ‘declining niche in the ecological relationship between science and society’ by the early twentieth century.12 The different models of science writing for the ‘general reader’, to use O’Connor’s term, were being reduced: ‘popular’ writing remained, but the older models in which authors addressed new contributions to knowledge to general readers were in abatement.13 As Bonney observed, the difficulty of keeping up with the latest research and terminology made synthetic treatises like the Principles rare and their non-specialist readers rarer.

While Bonney struck an elegiac tone, the developments he described were partially the result of a deliberate reorganisation of culture undertaken both by influential men of letters and by campaigning scientific researchers. The evolving contemporary definitions of ‘literature’, which in the early modern era simply referred to written works of all kinds, reveal traces of this process. Endeavours to map the etymological changes of this word have, however, revealed a craggy and irregular landscape. Despite significant developments around 1800 driven by the Romantic celebration of subjectivity, the now-familiar definition of ‘literature’ that implies exclusively aesthetic or emotive writing, usually fiction or poetry, was still unevenly accepted in the mid-nineteenth century.14 The spread of this new sense of ‘literature’ was buoyed by attempts to institutionalise the study of meritorious (and conservative) English writing in British schools and universities.15 Prominent intellectuals also began to define true ‘literature’ not merely as being different from science writing but as science’s opposite. This binary was suggested by poet William Wordsworth in his memorable, ambiguous juxtaposition of poetry with ‘Matter of fact, or Science’ in the 1802 edition of Lyrical Ballads.16 Wordsworth’s friend Thomas De Quincey widened the divide by conceiving of true literature as expressing timeless emotional power, rather than changeable knowledge.17 These definitions privileged poetry and ‘literature’ over scientific writing, although the division was used for other purposes as well. In 1852, the philosopher George Henry Lewes declared in the Westminster Review that ‘[s]cience is the expression of the forms and order of Nature; literature is the expression of the forms and order of human life’. Lewes’s admission that this distinction was required ‘at least for our present purpose’ (imperiously surveying ‘the literature of women’), rather than in all instances, indicated the novel and precarious nature of the binary.18 His definition nonetheless implied that he was a master of both domains.

The ‘strategic’ construction of what Gowan Dawson calls ‘localised boundaries’ between science and wider literary culture in the mid-nineteenth century was used to make a variety of claims for cultural prestige.19 Lewes’s assertion of the magisterial ability to span ‘literature’ and ‘science’ was quickly contested by the scientific naturalist and reformer Thomas Henry Huxley, who lobbied for the establishment of stricter hierarchies of authority to rank those engaged in scientific enterprise.20 Huxley challenged the generalist intellectual ethos of the Westminster Review, now remembered for its contributions from George Eliot, by condemning Lewes’s book-founded speculations as lacking ‘the discipline and knowledge which result from being a worker’.21 The practical experience in which Huxley found Lewes deficient indicated an important, and fairly novel, way to qualify oneself as a true ‘man of science’ (to use the gendered contemporary term). Lewes thus found himself placed on one side of the literary-scientific boundary he had helped to define. While Lewes was embarrassed by the scientific naturalist’s accusations, perimeters between science and literary culture were not built solely for the benefit of those, like Huxley, who were seeking more rigid qualifications for scientific expertise. This is demonstrated by Huxley’s alliance with another educational reformer, the humanist Matthew Arnold. Paul White argues that, ‘dividing culture exclusively between science and literature’, Huxley’s and Arnold’s parallel academic crusades ‘authorized their joint possession of its terrain’.22 By formalising the separate but notionally equally prestigious roles of science and literature into the modern education system, the territorial boundaries of culture could be defined and conquered. These newly specialised domains were both intended to be ruled over by men in shared patrician circles, like Arnold and Huxley themselves.

Science periodicals provided a more enclosed space for scientific communities to negotiate their own self-understanding.23 Melinda Baldwin shows that Nature, which quickly became the leading British science periodical after its founding in a more popular incarnation in 1869, was a key site for scientific self-fashioning. The prevailing view of Nature’s contributors, especially the younger generation of late Victorian savants, was that people ‘who simply read about science or who focused on the practical applications’ were less welcome in the periodical’s pages than those committed to ‘the creation of new knowledge’.24 This research-intensive stance was vigorously opposed elsewhere: Bernard Lightman identifies the rival ‘participatory ideal’ of a more inclusive model of science promoted, for example, in astronomer Richard Proctor’s periodical Knowledge (founded 1881).25 At this point we may return to Hutchinson, who, tellingly, wrote many articles for Knowledge.26 The most damaging attacks on his right to speak as a scientific authority, moreover, appeared in Nature. The reception of his palaeontological works constitutes a pertinent case in which the restricted definition of literature was a tool for clarifying the rules of scientific participation.

A Literary, Scientific, or Artistic Point of View

Lightman provides the most detailed biographical information on Hutchinson, although many aspects of this important writer’s life remain unknown.27 It is clear, however, that Hutchinson’s educational experiences were formative for his attitude towards science. Rugby School, where Hutchinson was taught and where his father, Thomas Neville Hutchinson, was Natural Science Master, stood in the vanguard of school-level science. In 1860, Rugby became the recipient of the first purpose-built science laboratory in a public school and, from 1864, two hours a week of middle-school science were compulsory.28 Hutchinson recalled that he had been ‘brought up in an atmosphere of laboratories and science’.29 He honed his scientific and journalistic skills in this fruitful environment, winning the Rugby School Natural History Society’s second prize for his essay ‘On Motive Power’ in 1872 and editing its journal for the years 1873 and 1874. Subsequently, taking his BA at St John’s College, Cambridge, he nurtured a side-interest in geology during a period in which St John’s geological tutors, such as Bonney (who became president of the Geological Society in 1884), were internationally renowned.30 After graduation, Hutchinson briefly taught science at Clifton College, Bristol, another institution at the national forefront of bringing science into education.31 Illness caused him to set aside his vocation as a Church of England clergyman not long after being ordained and, in 1890, after a brief spell of private tutoring, he moved to London to address his passion for science to mass readerships.32 Hutchinson’s career was thus born of an adolescence and young adulthood in which he absorbed a sense of the importance of education, science, and Christian faith.

Although he rarely published specialist research – and the key instance in which he did, discussed below, proved controversial – Hutchinson became a fellow of many scientific societies, including the Geological Society, and moved in circles alongside the leading savants of his day. His experiences made him an opinionated journalistic commentator on the state of science in society. Whether lamenting the school curriculum’s separation of science teaching from the moral instruction of the classics and the Bible in the sermonic Sunday Magazine, haranguing Daily Mail readers about ‘the neglect of science in everyday life’, or offering old boy wisdom in the Rugby School Meteor, Hutchinson promoted more effective popularisation of scientific information.33 He argued in Knowledge that

[t]he power of the press is enormous, and consequently the education of our very unscientific public, in these days, is largely in the hands of the journalists; on them rests a heavy responsibility. One is glad to see a popular newspaper, such as the Daily Mail, devoting some of its space to matters of this kind [rational sanitation], for in so doing it renders the nation a service of untold value.34

Beginning his career several decades after the franchise-broadening 1867 Reform Act and the 1870 Education Act, Hutchinson recognised that political democracy had arrived and addressed its implications for scientific practice. Fiercely democratic attitudes to science and science writing were an important part of the New Journalism, an accessible and often sensational form of American-styled reporting which is discussed in Chapter 3 (and of which the Daily Mail was a prominent organ).35 Hutchinson argued that if modern media technologies like the New Journalism, photographic reproduction techniques, and, later, the cinema, were not co-opted to edify the mass public, these same technologies would be exploited for the spread of amoral – or immoral – amusement.36

In Hutchinson’s experience, the most venerable scientific bodies were not adapting to this new media age. Writing in the general-interest natural history periodical Science-Gossip, he made his concerns explicit. Pre-empting ‘severe criticism on behalf of democracy’, Hutchinson suggested that ‘our learned societies might play a much more important part than they do in further spreading scientific knowledge’; instead, they ‘go on in the same humdrum way as they have always done, publishing their ponderous and almost unreadable reports’. For Hutchinson, the verbosity of these reports disguised superficiality: ‘[t]he sum and substance’ of a typical lengthy scientific paper, he argued, ‘could often be compressed into a single column of SCIENCE-GOSSIP’.37 He offered ‘progressive’ solutions befitting ‘the spirit of the age’, including the improvement of society libraries, the creation of publishing departments, annual conversazioni, and the admission of women.38 Hutchinson’s arguments implored a more outward-facing approach from scientific societies, with sharper focus on the communication of research to wider audiences. In this manner he cultivated the image of a moderniser. If there were any doubt about his own engagement with the democratic ‘spirit of the age’, Hutchinson even participated in an interview with the Pall Mall Gazette.39 This periodical’s former editor, New Journalism pioneer W. T. Stead, had introduced the interview, an American format that brought readers into the homes of celebrities, to British journalism.

Hutchinson aimed to spark mass interest in the earth sciences by writing the informative, readable books on the subject which he felt had been sparse in recent decades. The competitive late-century literary market was potentially a highly profitable one. To earn a living, Hutchinson combined his own enthusiasm and some novel subject matter with a canny understanding of readers’ expectations. Lightman’s study of his prose shows a largely derivative recycling of classic tropes of geological popularisation and the evolutionary epic, employing well-established imagery of nature as a book or stage and science as a fairy tale, framed within a subtle deployment of the clerical Christian mode.40 O’Connor characterises Hutchinson’s writing as ‘Familiar Didactic Exposition’, a common Victorian style in which a strong authorial voice complemented description with anecdotes and quotations.41 Hutchinson’s most distinctive technique was a frequent recourse to fiction and poetry in chapter epigraphs and the main body of his text. Extinct Monsters (1892), for instance, began by comparing the prehistoric world to ‘the fairy-land of Grimm or Lewis Carroll’.42 As Chapter 2 discusses in more detail, Hutchinson tantalisingly invoked the poem ‘Jabberwocky’ from Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871), only to insist that the ‘antique world’ was ‘not inhabited by “slithy toves” or “jabber-wocks,” but by real beasts’.43 Readers familiar with the famous Jabberwock would find new and genuine monsters to delight in, such as the recently discovered American dinosaurs: Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Brontosaurus. Copious ground-breaking illustrations (or ‘restorations’) of these dinosaurs by Hutchinson’s zoological artist, Joseph Smit, provided Extinct Monsters with a unique selling-point for gift-book consumers (Figures 1.2 and 3.2).

Figure 1.2 Joseph Smit’s pictorial restoration of Triceratops in Henry Neville Hutchinson, Extinct Monsters: A Popular Account of Some of the Larger Forms of Ancient Animal Life, rev. edn (London: Chapman & Hall, 1893), plate XI.

Hutchinson was guided in these endeavours by Arabella Buckley (1840–1929), one of the most successful popular science writers of the late nineteenth century. The former secretary of Lyell and author of books like The Fairy-Land of Science (1879), Buckley was best known for bringing evocative imagery, a maternal tone, and theistic frameworks to scientific exposition.44 She was also one of the first British writers to popularise reimagined dinosaurs. Although Buckley did not dwell upon this subject in her prose, the evolutionary work Winners in Life’s Race (1882) featured a series of innovative restorations of extinct animals executed by the artist Theo Carreras. Carreras’s depiction of Iguanodon as a bipedal animal was strikingly up to date.45 Buckley highlighted the fact that several of these ‘geological restorations’ were ‘here attempted, I believe, for the first time’, Carreras having carefully ‘followed my instructions’.46 Hutchinson’s debt to Buckley was extensive: his first book, The Autobiography of the Earth (1890), was published in London by Edward Stanford, Buckley’s usual publisher, and included a note thanking Buckley for allowing him to reproduce some of her illustrations ‘and for her valuable suggestions while the book was passing through the press’.47 Perhaps significantly, Smit, who would later become Hutchinson’s artistic partner, contributed to Buckley’s Winners in Life’s Race. Hutchinson called this ‘[o]ne of the best popular books on Natural History ever written’.48 As we shall see later in this chapter and in Chapter 2, the connection to Buckley and ‘the fairy tales of science’ that helped Hutchinson launch his career would be used both to reinforce and to attack his scientific reputation.

Thus inspired by Buckley’s example, Hutchinson wanted earth-science writing to make for gripping reading. In The Autobiography of the Earth, he dismissed ‘geological text-books’ as ‘dry, uninteresting, or even quite unintelligible’ to the ‘general reader’.49 Instead, for ‘those who follow the stony science’, he contested in The Story of the Hills (1892), ‘it is quite as fascinating as a modern romance, and a great deal more wonderful’.50 Thanks to earlier popularisers, the lost worlds of geology had long been associated with the dragon-infested realms of romance, but Hutchinson’s reference to ‘modern romance’ also held contemporary resonance.51 Since the mid-1880s, the single-volume adventure stories pioneered by authors such as Robert Louis Stevenson and H. Rider Haggard had dominated contemporary fiction, raising the claim that an over-realistic literary culture was now met with a ‘Revival of Romance’. The appeal of the fast-paced books of this ‘New Romance’ was attributed to their combination of fantastic events with a finely crafted semblance of realism.52 When told by a scientific storyteller, Hutchinson suggested, true geological processes required no such textual trickery to satisfy a reader’s desire for wonder and amusement. Science would never be as exciting as a ‘modern romance’, however, while its inner circles communicated in ‘almost unreadable reports’.53

Hutchinson’s contemporary, H. G. Wells, expressed exasperation at texts on the popular end of the newly polarised genres of science writing. He argued that most popular science writers produced lifeless texts that rarely sought to hook general audiences by imitating the ‘ingenious unravelling’ deployed in Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries.54 Thinking along similar lines, Hutchinson evoked the modern contrivances of the New Romance in his Prehistoric Man and Beast (1896), inviting readers to join him in pulling ‘the lever of Mr. Wells’s “time machine” to find ourselves travelling backwards into the past’.55 Hutchinson’s book was published just a year after Wells’s The Time Machine, the narrator of which speculates that the Time Traveller’s famous journey to the future may be followed by a journey backwards in deep time, ‘among the grotesque saurians, the huge reptilian brutes of the Jurassic times’.56 Later in Prehistoric Man and Beast, when Hutchinson compared an ancient tomb-engraving of a pair of feet to ‘some prehistoric “Trilby”’, all readers would have been familiar with his reference.57 George du Maurier’s sensational, risqué novel Trilby (1894), named after its female protagonist (whose bare feet are drawn on a wall by the artist Little Billee), was already one of the international bestsellers of the century. In the mass-market age of the Daily Mail, The Time Machine, and Trilby, science writing could cater to popular demand and reap both financial and educational rewards.

Hutchinson’s books regularly received glowing reviews, his works on palaeontology most of all. The Morning Post called Extinct Monsters, which reached at least five editions during the 1890s, ‘quite one of the most successful of recent undertakings in the field of popular science’.58 Sizing up its sequel, Creatures of Other Days (1894), the often-curmudgeonly Saturday Review judged that Hutchinson’s characteristic ‘clearness and simplicity of style’ produced an enjoyable text that ‘in less skilful hands … might degenerate into an arid list of defunct creatures’.59 These reviews were commonly accompanied by a generous selection of halftone reproductions of Smit’s restorations. For some reviewers, Hutchinson’s books were novelistic, with all the thrills of romance. The National Observer called Extinct Monsters ‘far more amusing than most novels’, while Science’s reviewer believed that readers would consume ‘chapter after chapter without any desire to lay the book down’, so ‘skilfully’ was it ‘interspersed’ with ‘striking incidents’.60 Fondly recalling the Shakespearean contribution to Science-Gossip with which I began this chapter, a reviewer in the same periodical judged that ‘from a literary, scientific, or artistic point of view’, Extinct Monsters was ‘the best book and most interesting book on popular geology since Hugh Miller’s time’, half a century earlier.61

As the comparison to Miller implied, Hutchinson was building not only upon Buckley’s recent natural histories but also upon a revered tradition of earth-science writing. He quoted at length classic texts by geologists from earlier in the century, such as Miller, Lyell, William Buckland, and Gideon Mantell, who had worked in a climate when geology was a more integrated part of literary culture. Hutchinson’s desire to entice wide audiences with the evocation of geology’s romance hearkened back to the graphic language of classics like Buckland’s Geology and Mineralogy (1836) and Mantell’s The Wonders of Geology (1838). By the standards of the 1890s, these books of the early and mid-century decades were generically multiple. Jonathan R. Topham observes, for instance, that Geology and Mineralogy had functioned as both attractive popularisation and new scientific research.62 At the end of the century, the difference in style and content between science writing for general readers and new contributions to scientific thought, magnified by the emphasis on primary research as the focus of the ‘man of science’, had diminished the opportunity for writers to span these genres.63 Hutchinson’s fondness for these earlier writings and his liminal position in the scientific community encouraged him to fight this crystallising status quo. While he intended his books to be readable for the general public, they were also his venue for entering printed scientific debate and he poured much time and effort into research. Extinct Monsters enjoyed a laudatory preface by the London Natural History Museum’s Keeper of Geology Henry Woodward; the preface of Creatures of Other Days was penned by the Museum’s director William Henry Flower.64 Both books, published by Chapman & Hall, were built upon assistance from leading scientific authorities and discussed the most recent research available. Smit’s restorations, in particular, were the first meticulous attempts to illustrate many of the new American dinosaurs discovered by Marsh and E. D. Cope as they might have appeared in life.

Although his books were ostensibly popular, and produced with some input from experts, Hutchinson did not modestly echo the opinions of his sources. Rather, in keeping with his persona as the reformer sweeping away scholarly detritus, he entered debates on controverted issues, sometimes taking a combative tone against the theories of authorities, living and dead. As such, his books strayed into the territory of the more authoritative reflective treatises.65 Dinosaurs, the most exciting discoveries of modern palaeontology, were the group on which he expressed his opinions most confidently. He argued, for example, that the concept of an evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds enjoyed popularity ‘partly, perhaps, in deference to so great an authority as Professor Huxley’.66 In this matter, Hutchinson positioned himself as a proponent of a generalist’s common sense. ‘Palæontologists tell us they are related’, he ventured in Creatures of Other Days, but ‘we confess to being not quite convinced’; instead, when one was to apply ‘reason’, the similarities between dinosaurs and birds were likely the same parallelisms of function that made whales appear similar to fishes.67 Common sense, Hutchinson implied, allowed him to see through knotty evolutionary problems that misled even accomplished naturalists like Huxley. Thus, his readers would be able to enjoy a book written by a man with all the knowledge of the latest scientific developments but no servility to jargon or status.

Literature Rather Than Science

Various esteemed men of science were unamused by Hutchinson’s adoption of the tone of an authority and by his attacks on specialist terminology. Their appraisals turned against Hutchinson his own calls for the democratisation of scientific participation, which had hinged upon the readability of scientific texts. Particularly in Nature, Hutchinson’s books became a front line in the policing of scientific participation, based upon purported differences between literary popularisation and truly scientific writing. During the most significant of these exchanges over scientific authority, the dinosaurs that the Extinct Monsters books were helping to make famous became objects of controversy.

Lightman briefly comments on the review of Extinct Monsters in Nature by ‘H. G. S.’68 The rarity of these initials in the palaeontological community, and the distinctive concerns about reptilian and dinosaurian taxonomy indicated in the review, point to the British savant Harry Govier Seeley, who later signed himself ‘H. G. S.’ in his reflective treatise Dragons of the Air (1901).69 Seeley was an accomplished if idiosyncratic geologist, palaeontologist, geographer, and zoologist who has received only occasional attention from historians.70 Particularly esteemed for his studies of the mammal-like Anomodont reptiles of South Africa and for his controversial work on the flying pterosaurs (which he called ‘Ornithosauria’), his most influential contribution to science was arguably his classification of the dinosaurs. Until his death in 1909, Seeley seems to have maintained a partially non-evolutionary idealist stance on palaeontology that was, at least in anglophone science, relatively unusual for its time. As a result, his often-cryptic discussions of the family relationships between extinct animals could baffle colleagues who otherwise recognised his skills, and this tended to separate him from the mainstream of palaeontological thought.71 Seeley nonetheless held a diverse array of important scientific positions over his lifetime, usually combining university work with broader educational activities aimed at the general public. The relationship between Seeley and Hutchinson is unclear. They may have met through the extended geological community of St John’s College, Cambridge: Seeley was a long-standing member, although he left his official position several years before Hutchinson matriculated there. From the 1890s they were both working in London and Hutchinson credited the ‘distinguished English geologist’ Seeley for providing him with minor assistance in the composition of Creatures of Other Days, although Seeley’s name was just one among many in the book’s copious acknowledgements.72 As was common in Victorian literary culture, any personal acquaintance did little to ameliorate the withering terms of Seeley’s reviews (or to encourage Hutchinson to adopt Seeley’s classifications).

Seeley’s review of Extinct Monsters outlined the grounds upon which his later definition of ‘literature’ was to be made. His primary criticism was the way that Hutchinson, ‘with second-hand information, speaks authoritatively’ about difficult issues of palaeontology.73 To Seeley, scientific authority simply could not be won without first-hand research. His complaint echoed the manner in which, forty years prior, Huxley had undermined Lewes based on errors caused by the latter’s lack of practical work, although Seeley’s critique went further. Noting that Hutchinson had ‘read much, and shown an excellent capacity for quotation’, he scathingly characterised him as a ventriloquist rather than an original thinker. Hutchinson ‘conscientiously endeavoured to tell the story which is contained in his quotations, but beyond this he does not pretend’ to critical understanding.74 The word ‘story’ did not carry the positive connotations that Hutchinson often intended for it. Instead, it stressed the distinction between sober research and a compilatory attempt to string together loosely understood ‘striking incidents’ (as the less sarcastic reviewer in Science had called them) into entertainment for the scientifically illiterate. Seeley directed this audience, which he suggested had no need for the most accurate details, to Extinct Monsters. Patronisingly commending it merely for being ‘an excellent book for boys and unlearned people’, ‘simply written, without any pretence at being scientific’, Seeley separated the book’s readership and author from the realm of scientific activity.75 While Hutchinson had appealed to a wide audience, including those with little palaeontological knowledge, the suggestion that the book made no ‘pretence at being scientific’ was belied by its authoritative voice.

Seeley phrased his complaints more succinctly when reviewing Hutchinson’s subsequent volume, Creatures of Other Days (1894). He immediately declared this ‘a work of literature rather than science’ which was ‘so full of reference to scientific facts and discoveries that it appears like a work of learning’. Seeley perceived Hutchinson’s deployment of repurposed information under an authoritative authorial persona to be akin, almost, to an act of deception. Hutchinson, despite possessing the capacity to seem learned, employed ‘no critical digest of the facts’ or ‘nomenclature’ while ‘impartially’ accepting material on palaeontology ‘which any author has supplied’. The result was a book of ‘unscientific attitude’ that tried to camouflage this fact.76 For Seeley, scientific writing was based on first-hand research and even intensive secondary reading without laborious primary activity could not provide a writer with the critical experience to compose anything other than literature. Popularisation (or an attempt at a reflective treatise) written by one unqualified to speak authoritatively, then, was literature. Literature was not a part of the same conversation as science. Unlike the earlier definitions of De Quincey and Lewes, who had compartmentalised writings on nature and on feeling, Seeley’s ‘literature’ was founded on the qualifications of the writer, not the subject matter. He made minimal reference to the book’s aesthetic qualities, the attributes which have typically been seen as differentiating science from literature in the eyes of critics. Reading these reviews conspicuously supports Baldwin’s argument that Nature was a crucial site in which the term ‘man of science’ was restrictively redefined to mean a specialist researcher. By defining literature in this way, Seeley suggested to his readers that it was surplus to scientific requirements. He did not disavow Hutchinson’s belief in the importance of wide scientific education; on the contrary, Seeley was an active lecturer and proponent of access to science.77 This did not mean that he was willing to lighten the relatively modern standards of expertise that constituted rightful authority.

As ‘H. G. S.’ suspected, Hutchinson’s lack of specialist standing was not always evident or significant to general readers. Reviewing Hutchinson’s later book of palaeoanthropological cartoons, Primeval Scenes (1899), the popular literary periodical Outlook considered the previous works of this ‘eminent scientist’ as ‘among the most authoritative’, while New York’s Sun and the British Pall Mall Gazette alike described Hutchinson as a ‘scientist’.78 The transcriber of the Department of Geology’s Visitors’ Book at the Natural History Museum struggled to pin down the man’s qualifications as well. For the most part, Hutchinson was, as he preferred to be known, ‘Revd.’, but on occasion he became simply ‘Mr.’ or ‘Dr.’79 He achieved his highest prominence in a short story by Eden Phillpotts: the titular clergyman of Phillpotts’s ‘The Archdeacon and the Deinosaurs’ (1901) associates the author of Extinct Monsters with ‘a thousand other eminent naturalists and palæontologists’, indiscriminately lumping together ‘Cuvier, or Huxley, or Owen, or Tyndall, or Darwin, or Geikie, or Marsh, or Zittel, or Hutchinson’.80 Famed for his knowledge of the earth sciences despite writing largely in popular works and letters to the editor, Hutchinson often gave the impression that he was an authoritative palaeontologist.

Classification of the Terrestrial Types of Saurians

The very necessity of differentiating between ‘literature’ and ‘science’ admitted the equivocal position of Hutchinson’s writings. Seeley had reason to be irritated: Hutchinson had effectively ignored his recent contention that ‘the Dinosauria has no existence as a natural group of animals, but includes two distinct types of animal structure’.81 Instead, Hutchinson used this supposedly unnatural term more frequently than any earlier populariser. Unusually for a nineteenth-century popular work on palaeontology, Extinct Monsters singled out dinosaurs for special attention: three chapters included the word ‘Dinosaurs’ (rather than the more typical ‘saurians’) in their titles, as did two chapters in Creatures of Other Days. Smit’s set of restorations was also the first serious attempt to depict American dinosaurs like Stegosaurus and Triceratops as they may have looked in life; American palaeontologists had usually shied away from publishing this kind of speculation. As many of the bare skeletons of these dinosaurs had initially been pictorially reassembled in Marsh’s articles, Hutchinson naturally turned to the Yale palaeontologist’s work for information. He referred colloquially to ‘Marsh’s monsters’ and roughly employed Marsh’s names for the sub-orders of dinosaurs, just one option among various competing classification systems.82 Seeley drily observed that Marsh’s ‘discoveries have inspired Mr. Smit’s pencil as much as they have influenced the author’s pen’.83 In Extinct Monsters, Hutchinson’s prefatory acknowledgements simply thanked the staff of the Natural History Museum for their assistance, but in Creatures of Other Days Marsh received by far the most substantial thanks for his ‘valuable suggestions and corrections, especially in the chapters dealing with the more recently discovered Dinosaurs’.84 I would speculate that Marsh, concerned about Hutchinson’s second-hand use of his research in Extinct Monsters, decided to take an active role in fashioning its sequel. Cope, Marsh’s bitter rival in the ‘Bone Wars’, also received some credit for assistance in this work, although in a far shorter paragraph. The American Naturalist, Cope’s mouthpiece, had previously lamented Hutchinson’s use of Marsh’s terms over those of Cope, including Stegosaurus instead of Hypsirhophus, Brontosaurus instead of Camarasaurus, and Triceratops instead of Agathaumas.85

In addition to falling on Marsh’s side of the Bone Wars, Hutchinson’s unusually heavy coverage of dinosaur palaeontology bypassed Seeley’s intervention of five years earlier. To demonstrate the significance of what may appear to be a pedantic issue of nomenclature, we must survey the history of the word ‘dinosaur’.86 Historians examining Richard Owen’s creation of the term, in 1842, to represent a poorly known series of elephantine lizards with a fused sacrum (Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylæosaurus), have observed that Owen’s coinage was at first used very sparingly, even by Owen himself, and was also immediately challenged.87 Gideon Mantell, Owen’s nemesis, was unconvinced.88 The German savant Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer, who had associated these same saurians together back in 1832, created his own group, the Pachypoda (‘thick feet’), in 1845.89 In the 1860s, Huxley built upon von Meyer’s and Mantell’s ideas, transforming Owen’s elephantine lizards into potential relatives of birds.90 He reluctantly retained the term ‘Dinosauria’, but it was demoted to a sub-order of Huxley’s new order, Ornithoscelida, named for their bird-like legs. The 1870s and 1880s saw the discovery of unprecedented quantities of dinosaur fossils outside of Britain, especially in the United States.91 With this bounty came the question of whether or not Owen’s category had any staying power. For Marsh, it did, albeit after serious renovation: in 1881 he defined the Dinosauria as an order in which most sub-orders were named after the structure of their feet (‘poda’): Sauropoda, Stegosauria, Ornithopoda, Theropoda, Hallopoda, and the more doubtful Cœluria.92 Almost immediately he upgraded Dinosauria to a sub-class and slightly revised the previous sub-orders, now orders.93 In 1886 Henry Woodward wrote to Marsh, informing him that the London Natural History Museum was adapting the dinosaur cabinets in its palaeontological gallery to Marsh’s neat classifications.94 As late as 1884, even an eminent Princeton geologist, Arnold Guyot, did not realise that ‘the lizard-like Iguanodon’ and ‘the Megalosaur’, British fossils named over half a century ago, actually belonged to the same family as the ‘bird-like’ American dinosaurs.95

Sometimes a confusing term even for experts, ‘dinosaur’ enjoyed little popular traction until the end of the nineteenth century, when its repeated use by American palaeontologists enhanced its publicity.96 Nonetheless, when Extinct Monsters was published in 1892, the word and especially its technical meaning were still fairly obscure beyond specialist circles. Earlier in the same year, a reviewer in Nature praised naturalist Richard Lydekker for his unapologetic use of ‘technical terms’ such as ‘“Condoyles,” “Dinosaurs,” “Iguanodons,” &c.’ in a popular book.97 The reviewer’s only caveat was a criticism of Lydekker’s use of the term ‘fish-lizard’ to refer to the aquatic reptile discovered by Mary Anning. The Ichthyosaurus’s famously convoluted name was ‘without need of translation’; instead, the reviewer suggested that ‘[i]t would have been in every way more reasonable if Mr. Lydekker had spoken of the Dinosaurs as “bird-lizards”’ (contradicting Lydekker’s own premature assertion that dinosaur was already ‘a household word’).98 Hutchinson’s subsequent liberal use of the term in the widely reviewed Extinct Monsters books diminished the once-prevalent sense that ‘dinosaur’ was a pedantic technical label. As we shall see in Chapter 2, his reviewers in the generalist press were quick to pick up on the significance of this relatively novel word.

After the turn of the century, the ‘second Jurassic dinosaur rush’ discussed in Chapter 3 spectacularly introduced giant dinosaurs into natural history museums in Europe and the United States.99 Some doubts remained, however, about the extent to which the word was understood by the public. In his general-interest book The Story of Reptile Life (1905), Natural History Museum osteologist William Plane Pycraft still considered ‘Dinosaurs’ to be a word used by the ‘serious student’ and deployed it sparingly, preferring ‘Earth Dragons’ or ‘land-dragon’.100 Writing for younger readers in 1910, he avoided the word entirely, calling the sauropod Cetiosaurus, the hind leg and tail of which had stood in the Museum for seven years, ‘an ancient British river dragon’.101 Nonetheless, by this time the word was much more familiar to general audiences, comprehensible enough to appear prominently and repeatedly in popular romances like Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) and Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Land That Time Forgot (1918).

Marsh’s groupings supported Owen’s assertion that the Dinosauria were a coherent group of animals, but Seeley disagreed. In 1887, he declared the Dinosauria an effectively non-existent conflation of two groups which ‘may be conveniently named the Ornithischia and the Saurischia’, the bird-hipped and the lizard-hipped.102 As the names imply, Seeley moved attention from the foot to the pelvis as the most characteristic attribute for general classification. His order Ornithischia combined Marsh’s Stegosauria and Ornithopoda and his order Saurischia combined Theropoda and Sauropoda, although Seeley argued that these two orders were not actually uniquely related. It is unlikely that Hutchinson intended a snub by ignoring this distinction; he may have been aware that Seeley’s nomenclature was not being adopted by naturalists. As German palaeontologist Freidrich von Huene noted in 1914, Seeley ‘maintained his classification until his death in 1909, but nobody followed him’.103 Seeley’s insistence on the literary status of Hutchinson’s book was not, therefore, simply an attempt to shut out arrogant popularisers; it was also an attempt to draw attention to an isolated view of the dinosaurs.

In Nature, Seeley considered it ‘unfortunate’ that Extinct Monsters gave ‘currency to nomenclature and classification of the terrestrial types of saurians which may not always prevail’, questioning whether it was ‘advantageous to have the Dinosaurs treated as a homogeneous group’, given the apparent distinctions between those ‘with a bird-like type of pelvis’ (Ornithischia) and those ‘with a reptilian type of pelvis’ (Saurischia). He expressed scepticism over Hutchinson’s use of ‘divisions adopted by Prof. Marsh’, which, as Seeley added disapprovingly, were additionally used in the Natural History Museum.104 Even without tackling the pressing inaccuracy of the Museum’s cabinets, Seeley was aware that many more people would read Hutchinson’s books and see their widely reproduced illustrations than would ever read his own material. The senior savant had little time for Smit’s pictorial restorations of dinosaurs, based as most of these were on the work of Marsh. Hutchinson, a man of limited scientific reputation but considerable literary savviness, had waded into a technical debate without providing readers with the proper context. Belonging to a small circle of established palaeontologists still sceptical of the explanatory value of evolutionary theory, Seeley would also have been disconcerted by Hutchinson’s enthusiastic application of evolution to palaeontology. If Seeley’s subsequent productions, The Story of the Earth in Past Ages (1895) and Dragons of the Air, were intended to combat works like Hutchinson’s, their drier technical style, comparative sparsity of lifelike restorations, and obscure taxonomic arrangements would have made them less attractive options for most general readers. These books included no illustrated attempts to bring his Saurischia and Ornithischia to life, despite the apparently radical differences that Seeley imagined between these two groups and Marsh’s dinosaurs.

As Seeley feared, Hutchinson’s influence on palaeontological popularisation was significant. Frederic Augustus Lucas, then curator of Comparative Anatomy at the United States National Museum (the Smithsonian), was particularly impressed. Describing to Congress the science behind speculative illustrations of extinct animals in 1900, Lucas naturally employed the name of ‘Mr. Hutchinson’ as an authority.105 Despite the fact that many of the most impressive palaeontological discoveries of the period were being made in the Western United States, no American popularisers had yet taken up the task of writing any serious popular works about them. This was perhaps owing to America’s more limited markets for popular science writing and to Cope’s and Marsh’s prioritisation of the tireless production of specialist contributions. The absence of such books was not simply Hutchinson’s self-aggrandising claim.106 His works, published in the United States by Appleton, provided American readers with the best overview of their country’s own booming palaeontology. As a result of this situation, when Lucas produced a popular work, Animals of the Past (1901), he felt obliged to admit that it was ‘somewhat on the lines’ of Hutchinson’s exemplar. ‘[W]ith books as with boats’, Lucas declared it ‘a good plan to build after a good model’.107 This ‘good model’ appears to have referred to Hutchinson’s conversational didactic tone, poetic quotations, high-quality restorations, and more or less chronological evolutionary progress through groups of extinct animals with little in the way of geology. Lucas’s appreciative words endured into the 1929 edition of Animals of the Past, two years after Hutchinson’s death.108 Notably, this book discussed dinosaurs rather than Saurischia or Ornithischia, as did all other books that followed, with or without admission, Hutchinson’s ‘good model’. These included E. Ray Lankester’s Extinct Animals (1905) and Henry Robert Knipe’s Evolution in the Past (1912). By the time of Knipe’s book, Lucas believed that ‘dinosaur’ was ‘as familiar in our mouths as household words’.109

The greatly increased familiarity of the dinosaurs was, to a significant degree that has not previously been recognised, Hutchinson’s doing. As an advertisement for his 1890s lecture series shows, he spoke on ‘Extinct Monsters’ at educational institutions including Eton and Rugby.110 His Geological Society obituary claimed that he was ‘known, at least by name, to a far wider circle than that which most of us can reach’ and ‘[h]is popular works on Extinct Monsters [sic] and the like are familiar to us all’.111 Indeed, plates from Extinct Monsters apparently remained on display in the fossil cabinets of the Sedgwick (formerly Woodwardian) Museum of Earth Sciences in Cambridge for a hundred and twenty years. H. G. Wells even placed Extinct Monsters in the school library of his ideal society.112 Perhaps the most unexpected example of Hutchinson’s reach is a reference to ‘those extinct monsters in Hutchinson’s book’ in correspondence between avant-garde Russian littérateurs Maxim Gorky and Leonid Andreyev.113 Gorky likely read Hutchinson in the Russian translation by palaeontologist Maria Pavlova.

Despite the proliferation of Marshian dinosaur palaeontology, Seeley’s Saurischia and Ornithischia did finally gain scientific currency: following their resuscitation by Huene in the 1910s, the Dinosauria came to be considered a probably unnatural grouping until its rehabilitation in the 1970s and 1980s.114 In the interim, it was common for popularisers to announce, as did palaeontologist William Elgin Swinton in his 1962 book Dinosaurs, that the titular term was ‘used only in a general and popular sense’ and that Owen’s category was ‘now important only for historical reasons’.115 The ‘general and popular’ survival of this once-obscure word during the half-century eclipse in which it was technically invalid, when specialists decried it and yet felt compelled to use it in the titles of their books, demonstrates the comprehensiveness of its popularisation at the turn of the century. Thinking in terms of what Topham calls the ‘feedback mechanism’ by which popular or non-elite science can shape elite practices, the proliferation of the word ‘dinosaur’ may have interesting implications for scholars of mid-twentieth-century palaeontology.116 Seeley’s objections to the Extinct Monsters books certainly constituted an attempt to regulate the potentially dangerous power of this feedback mechanism. He perceptively feared that ‘unlearned people’ – or, perhaps even worse, learned people – might take Hutchinson’s content seriously.117

Poetic Licence

Seeley clarified the ambiguous contents of Hutchinson’s science books for Nature’s readers, characterising them as ‘literature’. He hardly mentioned the allusions to poetry and novels that could have presented further evidence for his division between science and literature. It was a different reviewer in Nature who turned Hutchinson’s fondness for these forms into a weapon against his authority. As mentioned above, various reviewers echoed the language of Hutchinson himself in describing his books as possessing the readability of a good novel. Secord points out, however, that the remark that one’s science book was as readable as fiction held an implicit characterisation of the book as being designed to seduce the reader’s capacity for intellectual interrogation.118 While he makes this point in relation to the mid-nineteenth century, such connotations were perhaps even greater for the more generically distinct science writing of the fin de siècle. Invoking them exploited a blind spot in Hutchinson’s argument: attacking technical writing meant that its proponents could accuse him of being an unscientific populist.

In Prehistoric Man and Beast (1896), a far more contentious work than Extinct Monsters, Hutchinson expanded his focus to include palaeoanthropology and archaeology. He also adopted a more theistic tone, provocatively noting the evidence that the Book of ‘Genesis implies evolution’.119 Using similar terms to his Science-Gossip article of the previous year, Hutchinson argued that while palaeontological and archaeological writers of the past, like William Buckland, had offered ‘a fascinating story, full of romantic and weird interest’, latter-day savants had ‘obscured the romance by their “dry-as-dust” descriptions and ponderous reports’.120 As O’Connor notes, in Prehistoric Man and Beast Hutchinson’s unabashed desire for romance accompanied a ‘circular or mutually reinforcing’ argument that cited the scientific evidence for myths and fairy tales, and equally used these myths and fairy tales as data for scientific hypotheses.121 This controversial stance was accompanied, as always, by allusions to imaginative literature, but these were now woven into an argument that employed examples from fiction as evincing the prior existence of a dwarfish prehistoric race. This position was an elaboration upon the link between pygmies and fairies developed by the folklorist David MacRitchie.122 According to Hutchinson, Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhaüser (1845) ‘rightly represented’ the home of ‘the Queen of the Fairies’ as a ‘green berg, or green hill, into which the hero is tempted by the attractions of the dwarf-women’, and even Robert Browning’s poem ‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’ (1842) supplied ‘another example of the magical and thievish arts attributed to the dwarf people’ when ‘[a]llowing for “poetic licence”’.123 Imaginative literature was not now limited to epigraphs and similes but instead became part of the book’s scientific content.

This time, Nature’s reviewer was the geologist and archaeologist William Johnson Sollas, another former student of St John’s College from slightly before Hutchinson’s time.124 Somewhat offended by Hutchinson’s language, Sollas adroitly countered the populariser’s mockery by suggesting that the dry writers Hutchinson referred to ‘were too solicitous about the truth to care much about the romance’. Their sobriety was contrasted with Hutchinson, who Sollas suggested held ‘little sympathy with the technical details on which scientific results depend’. He accused Hutchinson of possessing the unscientific tendency to sacrifice strict truth to a ‘striking passage’. Such ‘striking’ romantic passages had attracted glowing reviews for the author’s previous works and Sollas alluded to this: if Hutchinson lacked the patience and precision that science required, what he instead possessed was ‘the true instinct of a writer for the populace’.125 For Sollas, as for Seeley, a crowd-pleasing journalistic reductiveness was what made Hutchinson’s books so appealing for modern mass audiences, such as those whom Hutchinson addressed most directly in his letters to the Daily Mail. This appeal to democratised mediocrity was, however, at odds with the restraint required in science. Scientific writing was here characterised by an absence of interest in the thrills of romance. This argument viewed from a different angle the division of literature and science proposed by Seeley, which had focused more squarely on primary research qualifications. Sollas’s distinction between ‘truth’ and ‘romance’ neutralised Hutchinson’s assertion that the truth itself was romantic and that science writing ought to reflect this. If Hutchinson intended his arguments about the scientific basis of fairy tales to be taken seriously by archaeologists, Sollas demanded a less romantic – or literary – register.

Even positive reviews, as the comparison of Hutchinson’s books to novels showed, could carry damaging suggestions that the literary nature of the work compromised its scientific accuracy. Reviewing Extinct Monsters, the Geological Magazine, whose editor, Woodward, had provided the book with its preface, perceived a ‘freshness about the whole thing which suggests “Alice in Wonderland[”]’ and confirmed that, although it could ‘not fail to interest geologists of all ages’, it was ‘safe’ for children.126 Hutchinson had indeed invoked Lewis Carroll in Extinct Monsters, knowing that the wide appeal of the Alice books would provide a diverting frame of reference for newcomers to palaeontology. His allusion tempted readers such as the Geological Magazine reviewer (almost certainly Woodward himself) to suggest that Extinct Monsters might be read in the same manner as an ingenious work of children’s literature. After all, Carroll’s books, filled with nonsense and paradoxes, were typically associated with the Christmas publishing season shared by Hutchinson’s own twelve-shilling gift-book.127 The Geological Magazine thus grouped Hutchinson’s text alongside the fanciful reading a child might be given at Christmas or New Year. This reaction contrasted with that of Seeley, who found it imperative to draw discredit upon the author before too many were fooled by the mass of ‘scientific facts’ that gave Creatures of Other Days the veneer of ‘a work of learning’.128 Nonetheless, he too had depicted Extinct Monsters as a piece of festive frivolity, comparing Smit’s restorations to the toys in the windows of London’s Lowther Arcade.129 Both reviewers suggested that Hutchinson’s books belonged to a lighter, more juvenile, and more literary realm. While the reviewer adopted a kinder tone than that of Seeley, the Geological Magazine, like Nature, was a self-consciously modern commercial journal aimed at specialists above all. Whether Hutchinson was belittled in Nature or praised in the Geological Magazine, readers of these periodicals were told that his books were intrinsically literature rather than science.

By the early twentieth century, the existing editions of Extinct Monsters were becoming outdated thanks to a spate of new discoveries. The Natural History Museum’s director E. Ray Lankester, another Nature stalwart, staunch secularist, and dedicated populariser, published his own book on prehistoric life, Extinct Animals (1905), to fill this gap in the market.130 The book was based on the children’s lecture series he delivered at the Royal Institution over the winter of 1903 to 1904. Avoiding the pitfalls encountered by Hutchinson, Lankester defined his parameters carefully. He trusted that, like his lectures, ‘this volume will not be regarded as anything more ambitious than an attempt to excite in young people an interest’ in palaeontology.131 These aims belied the fact that, as reporters gleefully observed, the packed Christmas audiences at his lectures had largely consisted of adults.132 Lankester, in any case, knew that specialist research was better aired elsewhere.

If his similar title and (intended) juvenile audience could be read as insinuations about the proper place of the earlier Extinct Monsters, Lankester’s assault on one of Hutchinson’s favourite literary tropes could hardly have been missed. The Natural History Museum director derided those popularisers who ‘talk about the “fairy tales of science”’, as Hutchinson did in so many of his books.133 Lankester declared that ‘[t]here never was a more inappropriate phrase: it is altogether wrong to speak of fairy tales having anything to do with science’.134 While Hutchinson had juxtaposed science and fairy tales in various ways, on some occasions showing their unexpected intimacies and on others framing science as a superior form of fairy tale, he always exploited their proximity. Now Lankester, just like Sollas before him, cleft science from the romantic and folkloric imagery that Hutchinson relished. This separation was consciously twentieth-century and unapologetically materialist: the fairy tales of science had been a staple of popularisation in the mid-Victorian period, most famously deployed by Buckley, who was another implicit target of Lankester’s mockery.135 He thus instructed twentieth-century readers to engage with science and literature in the proper way: as separate domains. In so doing, Lankester implicitly feminised the latter category – fairy tales, Buckley, Hutchinson, and all. Science, in contrast, belonged to a realm of empirical masculinity in which ‘you can test what you are told’.136

The True Shape

By 1905, when Lankester’s book was published, Hutchinson’s fame had already peaked. The 1890s had been the high point of his cultural visibility and thus the period in which concerned savants saw the most pressing need to temper his influence. Hutchinson’s revised but largely recycled 1910 compilation work, Extinct Monsters and Creatures of Other Days, received a short but benign review in Nature, written by Hutchinson’s sometime-colleague Lydekker.137 Lately Hutchinson’s interests had strayed towards astronomy, but during the Great War he made a new attempt to intervene on dinosaurian anatomy. This intervention raised the fraught question of his place in the palaeontological community more starkly than ever before. The bold new project, which will be the subject of the remainder of this chapter, centred on Hutchinson’s model of the most famous dinosaur in the world: Diplodocus carnegii (sometimes spelt carnegiei). Ilja Nieuwland and Dawson both briefly discuss Hutchinson’s contribution to the debates surrounding Diplodocus, but nobody has yet explored its intriguing demonstration of the changing nature of scientific writing and publishing.138

Lifelike models of extinct animals had been used for didactic purposes since the erection of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s Crystal Palace statues in 1854.139 Although little is known about the process of their manufacture, Hutchinson designed at least five models in the 1890s. Unlike Hawkins, Hutchinson exclusively produced models of genera for which complete skeletal remains were known. This was a counter-measure to prevent his designs from becoming obsolete as rapidly as Hawkins’s restorations of dinosaurs as elephantine lizards. He produced papier mâché models of approximately twelve to twenty inches depicting the mammals Dinoceras and Megatherium, the aquatic reptile Plesiosaurus, and the dinosaurs Iguanodon and Triceratops. The first four models were sold by the scientific instrument company Messrs. Newman of Newman Street, while the last was on sale for ten shillings, possibly from Hutchinson’s own home.140 In 1916 he designed his Diplodocus and, in 1922, one Edward Godwin helped him produce a model of the marine reptile Peloneustes philarchus.141

Keen for forms of scientific education that sidestepped jargon, Hutchinson (like Hawkins before him) believed that models were ideal media for expressing complex ideas.142 Unlike Smit’s pictorial restorations, these casts provided a three-dimensional perspective that could be carefully studied. Hutchinson boasted to the anthropologist Augustus Pitt-Rivers that his model of Plesiosaurus was ‘unique, because made from the only skeleton of that animal that has ever been set up like that of a living animal; and so it shows for the first time, the true shape’.143 ‘The public like models such as these’, he later insisted, in an attempt to persuade the Keeper of Geology at the Natural History Museum to display his Peloneustes in the public gallery, ‘for they really do help them’. It seemed ‘a pity to bury them away in your library’.144 Such was Hutchinson’s enthusiasm for models that his tactless contribution to a discussion on the ‘Cartographic Needs of Physical Geography’ at the Royal Geographical Society was to disparage maps. Models, to which he attached ‘enormous importance’, were ‘worth a great deal more than maps’.145

Hutchinson’s 1890s models proved less controversial than the restorations that aroused Seeley’s wrath, being based upon well-known specimens. Diplodocus, in contrast, had recently been the subject of an international dispute. Thanks to the resources of the industrialist Andrew Carnegie, casts of the complete skeleton of this American dinosaur were gifted to museums all around the world in the early twentieth century. Alongside his wife, Bertha (née Bertha Hasluck), Hutchinson attended Carnegie’s official unveiling of the Natural History Museum’s Diplodocus on 12 May 1905.146 The subsequent disagreement over this dinosaur’s gait has become one of the most famous episodes in the history of palaeontology.147 William Jacob Holland, director of the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh and the driving force behind the Diplodocus cast project, followed John Bell Hatcher’s argument that it was a straight-legged dinosaur. In 1908, another American naturalist, Oliver Perry Hay, provoked a stir by arguing for a sprawling, crocodilian stance just as Gustav Tornier of the Berlin Museum of Zoology was independently proposing a similar idea. The conflict between Holland and Tornier has typically been presented as nationalist rancour between growing empires, although Nieuwland argues that Tornier’s involvement ‘should probably be seen mainly in the light of intra-German scientific disciplinary struggles’.148 By the time Hutchinson completed his Diplodocus project in 1917, the heat of the controversy had died down. Even in the 1910 edition of Extinct Monsters he had expressed only mild interest, explaining that Tornier ‘thinks its legs were more or less bent’, a ‘view which is partially expressed in our restoration’ by Smit.149

Subsequently, Hutchinson took Diplodocus more seriously. The dinosaur itself had been given fresh resonance in wartime: the newly invented tanks on the Western Front were being compared to the notoriously bulky sauropod.150 Although it is not clear when exactly he began, Hutchinson had produced a four-foot-long model of a Tornieresque reptile-legged Diplodocus and four smaller plaster casts by 14 May 1916. In a letter post-dated ‘1917’, he explained that he had ‘sawn off’ and reattached the dinosaur’s head, which may explain why the head of the original model currently in storage at the Natural History Museum (Figure 1.3) looks slightly different from the photograph reproduced in his Geological Magazine paper on the subject.151 Hutchinson claimed that the model had been endorsed by Charles William Andrews and William Plane Pycraft, both naturalists at the Museum.152 On 23 May 1916, Hutchinson proudly exhibited it before the Zoological Society.153 He delivered one small cast to the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge and gave another to the Natural History Museum, apparently along with the four-foot original, advising that it ‘be put somewhere where it can be seen by the public’ where, presumably, it would act as a counterpoint to the Museum’s straight-legged skeleton.154 This request was seemingly not enacted. Another copy was given to the Geological Society and displayed in 1920.155 The final reduced-size copy was presented to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History on 11 March 1922.156

Figure 1.3 Hutchinson’s four-foot Diplodocus model, currently in storage at the Department of Palaeontology at the Natural History Museum, London.

The prestigious societies and institutions before which Hutchinson exhibited his redesigned Diplodocus indicate that he intended his model to contribute to the international conversation on the dinosaur’s posture. For Hutchinson, this appears to have been a period of resurgent interest in being taken seriously as a palaeontological thinker: he joined the Council of the Palaeontographical Society in March 1917, a post which he held until April 1919. Critics in Nature had dismissed his earlier interventions as too presumptuous for a mere populariser, but Hutchinson now drafted a piece of scientific writing that was not intended to be popularisation at all: his study of the Diplodocus was to be a rigorously evidenced article in the Geological Magazine, edited by his friend Henry Woodward. Woodward was known to express editorial generosity even to authors whose opinions tended towards unorthodoxy, a stance that had helped the initially struggling specialist journal to maintain a commercial foothold.157 Hutchinson presumably hoped for a sympathetic hearing.

Knowledge in Water-Tight Compartments

When Hutchinson offered his model to the Sedgwick Museum in 1916, he had written an accompanying paper. The paper resurfaces in a letter dated 24 May 1917. At some point during this period, Hutchinson suffered from a nervous breakdown and was further distressed to hear that his paper had been rejected by the Geological Magazine. From Cromer, Norfolk, where he was apparently convalescing, Hutchinson wrote a gloomy letter to the Natural History Museum’s Keeper of Geology, Arthur Smith Woodward (a man unrelated to the former Keeper and ongoing Geological Magazine editor Henry Woodward) to enquire about the rejection. He confessed that he ‘rather purposely did not read any other papers’ on the famous American dinosaur aside from Holland’s and Hatcher’s, an odd decision given that his perspective on Diplodocus resembled that of Hay and Tornier, and acknowledged that significant alterations were necessary to make it ‘suitable’. He was, unfortunately, ‘far too weak and depressed to do any work of this sort’.158 Although Hutchinson accepted the deficiencies of his submission, he let loose a frustrated outburst in which he highlighted many of the issues with which this chapter has been concerned.

In Hutchinson’s view, modern divisions between scientists and the public, literature and science, and science and faith were the disturbing results of the over-specialisation of knowledge. An apparently never-completed book was intended to address this situation:

As yo[u] say, my scheme is “Not Science”[.] But that is just why I am doing it Sci[en]ce make[s] a mistake in keeping Knowledge in water-tight compartments[.] It is Philosophy … The mystery of Evolution will never be solved by the pure scientist. It wants the help of the Poet and the Philosopher. and esp the religious philosopher such as the poet Wordsworth. Look at Swedenborg, what marvellous insight he had[.] [H]e anticipated many modern discoveries esp in Physiology.159

His allusion to William Wordsworth in this context was a prevalent trope at the time: the religious comforts of Wordsworthian nature poetry were seen as ameliorating the harsh implications of natural selection and extinction.160 Hutchinson was a firm believer in evolutionary theory, but his confidence in the directionless mechanism of natural selection had rapidly diminished since 1892 and by the late Edwardian period he was arguing for a theistic, benevolent, and will-driven mode of evolution.161 He now told Smith Woodward that religious poets were not merely a psychological ballast against amoral nature; they were actually capable of insights unavailable to those studying evolution from an atheistic, materialist perspective. The eighteenth-century thinker and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg was valuable evidence for this argument: Swedenborg had recently been discovered to have gained physiological insights despite working in a much less specialised, and far more Christian, intellectual climate.162

Hutchinson went on to suggest that the Geological Magazine ‘would have a far wider circulation if it were not written in such a pedantic style’, calling it ‘far beyond the reach of the ordinary geologist’.163 Indeed, geology was considered a particularly jargon-heavy science.164 Hutchinson had long warned that this technical vocabulary excluded the general public from the discipline, but back in 1895 he had characterised the ‘excellent’ Geological Magazine as a readable alternative to prolix scientific society journals, at least for those with some geological knowledge.165 Not so in 1917: he now felt that it was even ostracising people like himself. Hutchinson’s confusion over his status in the scientific community is understandable: the earth sciences remained very unevenly professionalised in Britain until the Second World War, allowing the ambiguous identities typical of Victorian practitioners to endure to some degree.166 Hutchinson continued to consider himself an ‘ordinary geologist’ (which, in contemporary terms, meant that he was also a palaeontologist), even in the pages of the Geological Magazine, to which he sporadically contributed small items like book reviews.167 If new primary contributions to knowledge had become a vital part of what made one a geologist, however, then Hutchinson was not making the cut. When his paper on Diplodocus was rejected, he considered submitting it to the less prestigious Knowledge instead, as was his usual practice.

Hutchinson’s description of an atomising scientific community was, like Seeley’s ‘literature’, a tactical construct, not least because his Diplodocus project had cost a considerable £20 or more. Following a conciliatory letter from editor Henry Woodward explaining how the article might be altered for publication, Hutchinson wrote again to Smith Woodward. Rather unorthodoxically, he asked if the latter might ‘add a Note or two where you think it advisable Esp about the papers by Hay and Tornier’ and mark these editorial sections of the published paper with Smith Woodward’s own name.168 He added that Henry Woodward had insisted that the paper appear in two parts. The final product, ‘Observations on the Reconstructed Skeleton of the Dinosaurian Reptile Diplodocus Carnegiei as Set Up by Dr. W. J. Holland in the Natural History Museum in London, and an Attempt to Restore It by Means of a Model’, was published in the August 1917 volume of the periodical.

The published paper was, in fact, neither co-authored nor in two parts and the exclamation-mark-laden script was tonally more consistent with Hutchinson’s popular texts than with the specialist papers it accompanied. Indeed, he cited his own Extinct Monsters and Creatures of Other Days, handily ‘now in one vol’.169 The paper began with a familiar dismissal of obscurantism, insisting that ‘the writer has endeavoured to consider this skeleton in a common-sense way, and to arrange the limbs with reference to ordinary mechanical principles’.170 This included a method of demonstrating the correct articulation of bones ‘by means of a pocket-handkerchief’.171 Such comments recalled the attitudes expressed in Creatures of Other Days, in which Hutchinson had confessed ‘to being not quite convinced’ by Huxley’s proposal that birds were related to dinosaurs, preferring to ‘reason the matter out’ instead.172 ‘Imagination fails!’ scoffed Hutchinson at the fallacies of the earlier reconstructions of Diplodocus.173