Introduction

In 1919 a collective of indigenous women on Sumatra's east coast printed the inaugural issue of the periodical Perempoean Bergerak (‘Woman on the Move’). A platform for social and political emancipation (kemadjoean, Malay for advancement, progress), the journal's first editorial reflected on how the condition of women was inscribed by ‘the house, infant-feeding, child-rearing, hygiene, religion, and indigenous feminism’, which they explained as a ‘feminism we wish to pursue in a clean way so that it won't get opposed. We won't cross religion nor tradition.’Footnote 1

Ann Stoler has argued that ‘it is imperial-wide discourses that linked children's health programmes to racial survival, tied increased campaigns for domestic hygiene to colonial expansion, made child-rearing an imperial and class duty, and cast white women as the bearers of a more racist imperial order and the custodians of their desire-driven, immoral men’.Footnote 2 By the turn of the twentieth century, this imperialist project had turned to ‘modernization’. Broadcast through child-rearing columns in women's magazines and commodified through the marketing of food for children and home appliances, the image of modern motherhood (as theorized by Rima AppleFootnote 3) reached the colonized, projecting yet another example of European civilizational superiority,Footnote 4 but also offering colonized women a clear point of entry into modernity. It assumed not only aspiration to and acceptance of European ‘modern’ ways, but also the explicit rejection of indigenous (‘traditional’) practices deemed ‘backward’ by the colonial establishment. Elsbeth Locher-Scholten has argued that the European model of ‘motherhood was an emblem of modernity in the colony. Modern mothers, healthily and hygienically caring for the upbringing of their children, were considered the carriers of modernity by Europeans and educated Indonesians.’Footnote 5 But I intend to present a more nuanced approach to the nexus of modernity, health, and motherhood in the Dutch colony. Women contributed substantially to the emergence of Indonesia as an advanced nation-state, not as mere ‘maternal envelopes’, or ‘vessels’ for children, or simply modelling European behaviour.Footnote 6 Rather, indigenous women crafted a discursive space in which they negotiated the boundaries between tradition and modernity, turning the domestic sphere into a space for agentive action.

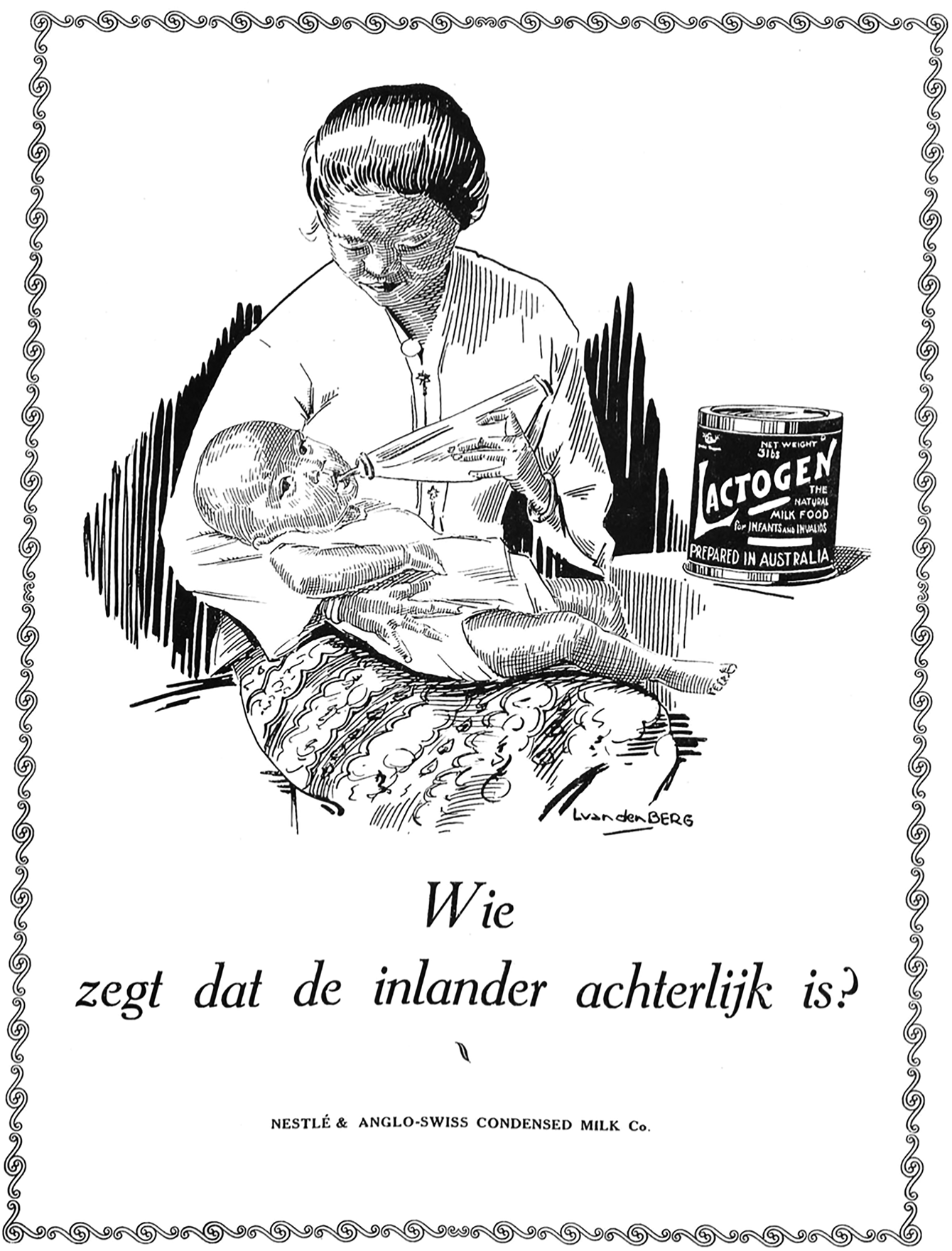

Women in Java and Sumatra embraced schedule-feeding and -sleeping, scientific measuring of feeds and growth, and physical distancing from the child during the day and night, as markers of outward modernity that required technologically advanced equipment such as watches and scales, baby-carriages and cribs. And yet, even though it was breastmilk substitutes more than any other commercial product that represented this shift, with bottle-feeding depicted as the ultimate marker of modern and scientific motherhood (see Figures 1, 2, and 3), this form of infant feeding was often criticized and rejected as less nutritious and more prone to bacterial contamination. This attitude was not a simple rejection of modernity or Western influences, as much more complex dynamics were at play. As also made explicit in the 1919 editorial quoted above, women in Java and Sumatra took ‘hygiene’ (and therefore ‘health’) to be a core element of colonial modernity, and they thus proceeded to redefine the trajectory of kemadjoean (‘progress’) to shape a singular framework that was centred on understandings and perceptions of healthfulness; I name this paradigm ‘healthy progress’.

Figure 1. Advertisement for Lactogen milk powder: ‘Who says the native is backward?’. Source: D'Orient, 1926.

Figure 2. Advertisement for Nutricia milk. Source: Huisvrouw in Indië, no. 10, October 1932.

Figure 3. Advertisement for Fissan cream. Source: Vereeniging van Huisvrouwen Medan, no. 11, November 1936.

In a changing socio-political context, affected by the so-called Ethical Policy of the Dutch (begun in 1901), the Japanese occupation (1942–1945), and the Indonesian nation-state (from the beginning of the Revolution in 1945 onwards), public health propaganda that harnessed progress (later, ‘development’) to hygiene, good nutrition, and overall health remained a constant feature of these projects of modernity (and still is, in fact, as indicated by the Millennium Development Goals). Under these circumstances, women became primary agents of Indonesia's advancement through their role as custodians and promoters of hygiene. Far from being passive executors of policies and visions drafted by men—largely meant to control the environment, human bodies and their behaviour, and food production—women deployed their own agency and negotiation efforts between ‘tradition’ and ‘hygienic modernity’ (to borrow from Ruth RogaskiFootnote 7) to actualize this framing of a ‘healthy progress’. This paradigm was articulated in the Malay-language press in elaborations over nutrition and child-care, with decisions being made by choosing from, and negotiating between, multiple models of behaviour in order to achieve what these women individually deemed most ‘healthful’.

In this article I piece together the views of writers who engaged in conversations about health, child-rearing, child-feeding, and socio-political progress in Java and Sumatra, situated against the backdrop of imperial policies of hygienic modernity and public health. In this exploration it becomes evident that in late-colonial Java and Sumatra, the encounter between everyday bodily practices of health (dictated by colonial forms of hygienic modernity) and middle- and upper-class women's aspirations to progress—which were deeply informed by indigenous (‘traditional’) knowledge—gave shape to an original discourse and practice of modern motherhood. These colonized women's conscious appropriation and reformulation of the colonial discourse on scientific modernity were grounded in their awareness of the racial project of control of their bodies; and the promotion of breastfeeding was a way to affirm ‘native superiority’Footnote 8 and a path to progress that shared the underlying conditions for Western modern motherhood, but not its modalities as projected by the overwhelming emergent consumer culture.Footnote 9 Whereas many European doctors in both Europe and the colonies had for decades advocated for the benefits of breastfeeding, society more broadly rejected this tenet in favour of measurable feeds, physical freedom, and sexualized bodies; in the colonies, the differentiation of Europeans from indigenous practices was crucial. Beginning in the mid-1920s, but more vehemently so in the 1930s, the Dutch popular discourse on infant-care was dominated by subtle and explicit endorsements of bottle-feeding.

Examining the processes of negotiation and subversion that emerged in indigenous women's writings provides a productive space to question and reframe scholarly understandings of ‘modernity’ as a category of analysis. Arnout van der Meer has focused on the ‘disturbances of the colonial performance’ of power as a source for political change in Java.Footnote 10 In another recent publication Tom Hoogervorst has proposed that Malay translations of European popular literature deployed ‘deliberate strategies’Footnote 11 to introduce ‘a powerful counter-discourse to Europe's hegemony over language, knowledge, and information’.Footnote 12 I similarly argue that the writings analysed here translated knowledge using indigenous paradigms as a way to subvert power hierarchies in the colony.

There is no denying the hegemonic power of European framings of hygienic modernity or modern motherhood in early twentieth-century Java and Sumatra. But in this colonial setting, a ‘conscious’ or ‘self-aware’Footnote 13 response to this hegemony was to take the essence of what was being framed as ‘modern’ (in this case, health mediated through hygiene and nutrition) and show that it existed both before and without European intervention. This response required engaging with the meaning of the term, while disengaging from the term itself. The writings analysed here made an explicit distinction between ‘modern/ity’ (moderen/kemoderenan) and ‘being advanced’ or ‘progressive advancement’ (madjoe/kemadjoean), addressing head-on the cultural roots of ‘modernity’. All things described as moderen were inevitably of Euro-American origins. As such, they often carried ‘negative connotations in Malay publications’ as innovations that undermined the integrity of local societies,Footnote 14 potentially ‘lead[ing] to an erasure of traditional Asian principles’.Footnote 15 Authors writing in Malay avoided endorsing Westernization as the sole path ahead by employing instead the term kemadjoean, a form of ‘progress’—technological as much as societal—which could have roots in indigenous, Euro-American, Chinese, Indian, or Japanese models. This was not an ‘anti-modern’ position, but rather the promotion of a platform in which a specific ‘tradition’ (indigenous practice) was redefined as madjoe by invoking the hygiene and health standards of Western modernity. It is on these grounds that we can push forward current scholarly discussions on multiple modernities.Footnote 16

In the following pages I focus on how indigenous women deployed their discursive agency on issues of motherhood and progress as a tool to undermine the colonial project, following their expressions of such ideas in local periodicals in 1920s–1930s Indonesia (with occasional nods back to the nineteenth century and ahead to the 1940s–1950s). A few qualifications are necessary: Who were these women? ‘Local’ to where? And why ‘Indonesia’? First of all, we know little, if anything at all, of the women I write about. We might have a name and could speculate on their place of origin or political affiliation; although I refrain from speculation, I also want to preserve the memory of their names as I give voice to their thoughts. Two more considerations are necessary here: class and education. Throughout the article I use class referents, rather than ethnicity. These women were literate and thus had access to some form of education—this I take as an indication that they are likely to have been representative of a rising middle class, possibly of the local aristocracy or new bureaucracy. This would appear to limit the scope and impact of my argument, but, while calculating that probably only about 2.2 per cent of indigenous women in 1930s Indonesia were literate, Barbara Hatley and Susan Blackburn have also noted that periodicals were significant in documenting new ideas that were likely to have been widespread.Footnote 17 As also highlighted by Doris Jedamski, publications were often read aloud, expanding their circle of influence.Footnote 18 In terms of racial identity, I work on the assumption that the articles that appeared in Dutch-language magazines were written and read by either Dutch women living in the colony or indigenous women (some possibly Eurasian, we do not know) who had received a European education; for writings in Malay appearing in local women's periodicals, I assume that both authorship and audience rested in indigenous women. Here ‘local’ women and periodicals mostly refer to Java and Sumatra; I refrain from using the adjective ‘native’ (the legal term deployed by the Dutch), unless in quotation, and privilege instead the term ‘indigenous’. I chose these two islands as they have been home to the vast majority of the archipelago's population and they had the most thriving vernacular press in the early twentieth century. Some of these Malay-language publications were sponsored by the colonial government, others were mouthpieces of local or national indigenous organizations, and some others were printed by individuals with the means (or subscription funds) to do so. In the text, I offer whatever information is available about each publication I mention. Lastly, I prefer using the toponym ‘Indonesia’ to ‘Dutch East Indies’, especially when I am not referring to colonial policies or visions but am taking the perspective of the colonized subject; as clearly laid out by Bob Elson, the ‘idea of Indonesia’ was well ingrained at the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 19

As the Dutch Ethical Policy set in motion a modernization project for the East Indies which harnessed, among other things, hygiene and health literacy, women were by default placed at the forefront of this endeavour. In combination with other developments—such as expanded schooling opportunities, socio-political mobilization, and growing anti-colonial feelings—some women became active in reformulating the ‘new’ knowledge they were being exposed to in indigenous and Islamic paradigms. Through this discursive process, the dichotomy modernity/European/metropole and backward/indigenous/colony was bridged and, at times, subverted as indigenous and Islamic practices of child rearing were framed as ‘modern’. This focus on motherhood is intended as a window on a much broader dynamic that saw women as key players in redefining ‘modernity’ as a non-exclusively Westernizing phenomenon. Parallel negotiations are evident also, for example, in clothing, behaviour, and food preparation and consumption.Footnote 20

The vast scholarship on ‘modernity’ has predominantly portrayed a relationship of tensions and dualities that can only find resolution through rupture;Footnote 21 when we turn to the study of women's engagement with tradition and modernity, scholars of nationalism have substituted this trope of rupture with one of functional gendered duality, in which women were the gatekeepers of tradition in otherwise modernizing societies.Footnote 22 In the context of Indonesia, Barbara Hatley and Susan Blackburn posited that cleanliness and hygiene were key elements of the ‘modern woman’, who nevertheless also needed to be ‘able to maintain traditional cultural and spiritual values’.Footnote 23 As important as this point is, having been proposed by many nationalist leaders, including Indonesia's first president Sukarno,Footnote 24 I find it nonetheless analytically limiting.

The work of Alys Weinbaum, Tani Barlow, and the Modern Girl Around the World Research Group has opened new windows as they shifted their focus to women's discursive and material agency. As Weinbaum et al. have demonstrated, the entanglements of capitalism, globalization, print culture, and ‘the visual economy’ enabled the synchronous emergence of ‘modern girls’. These girls—‘denot[ing] an up-to-date and youthful femininity’Footnote 25—engaged with foreign representations of modernity, ‘exerci[sing] agency as consumers and social actors’.Footnote 26 As most explicitly laid out by Priti Ramamurthy in the setting of colonial India, film stars embodied and represented hybrid fashions, at times presenting themselves in ‘traditional’ clothing but largely ‘appropriating, rather than rejecting, western codes of modernity’.Footnote 27 In more recent work coming out of Southeast Asian historiography, Chie Ikeya has similarly illustrated how in British Burma the ‘new woman’ was an ‘intermediary between the local and the global’.Footnote 28

Java and Sumatra were no different. There too, indigenous women were exposed to advertisements that propagated global images of gendered consumer modernity, and thus fashioned themselves—in terms of clothing, cosmetics, hairstyles, and behaviour—at the intersection of Western examples and local models.Footnote 29 The advertisements printed in Dutch-, Malay-, Sino-Malay-, Javanese-, and Sundanese-language periodicals marketed household appliances, preserved foods, and anti-bacterial soaps for body, floors, and laundry; new fashions for clothing and furniture; and foreign cars and radios. European products, like their practices, were emblematic of modernity qua new and European.Footnote 30 But again, scholarship that addresses the role of Javanese women as carriers of this modernity through their consumer power has also fallen in line with the nationalistic argument, with Hoogervorst and Schulte-Nordholt concluding that it was ‘the task of women to withstand the destructive elements of modernity’ which were conveyed through advertisements.Footnote 31

In this article I develop these insights, by attempting to move beyond them. I build on Elsbeth Locher-Scholten's work on women in colonial Indonesia to expand her approach to European motherhood as an ‘emblem of modernity’ by inserting indigenous perspectives and practices. I appreciate Hoogervorst and Schulte-Nordholt's reflection on Javanese women's consumer power and the idea of a ‘modernity for sale’ in the Indies, but reject their concluding assessment quoted above. Also, while I embrace Weinbaum et al.'s framework of the ‘modern girl’ ‘as a heuristic device’—exploring visual representations of modernity, ‘complicating histories of commodity capitalism [and] consumption’, the incorporation of local elements, and contributions to analysis of nationalism and progressFootnote 32—I suggest that much of it remains valid even when we substitute the youthful, autonomous, and frivolous modern girl for grown women, and more specifically mothers. The role of mothering in the imperial project of Dutch colonialism percolated and emerged in the visual culture of Indonesia. Many of the advertisements promoted images of new European modes of (and products for) mothering, often latching on to recent scientific discoveries, such as germs and vitamins. Products promising a baby's healthy growth and indicative of a mother's modern outlook were also particularly powerful as European observers had described indigenous child-rearing practices (especially baby-carrying and breastfeeding) as ‘primitive’ and ‘backward’, at best ‘exotic’—two ongoing tropes of Orientalism (see Figure 4). However, all this did not translate into exclusive aspiration to and adoption of Dutch modes of being by those who envisioned themselves as madjoe (advanced).

Figure 4. ‘Vrowenweelde’ (Women's abundance). Source: Huisvrouw in Indië, no. 12, December 1937.

As I explore in detail in the following pages through the case of infant-feeding, women's writings illustrate that the path forward was far more complex than the dichotomous choice between imitation and rejection, or hybridity. They showed a path to progress without rupture or duality: they rejected alternatives to breastfeeding, but not as a principle of traditionalism, whether as a sign of deference for ancestral practices or a bulwark against Westernization. Turned into the main executors of the colonial project of modernity through their role as custodians of health, they deployed this embodied experience in their writings, crafting a new—negotiated—discourse of kemadjoean in which indigenous knowledge and practices (‘tradition’) were redefined as progress by invoking hygiene and nutritiousness. Specifically, they argued that breastfeeding was a better match to contemporary paradigms of European modernity, and criticized other forms of feeding as unhygienic and non-nutritious, and therefore as lacking in Western-defined modernity.

In the next three sections I first explore the historical circumstances that brought women to the centre of the colonial project of modernity as custodians of hygiene in selected locales in Europe and Asia. Then I move on to analyse Dutch- and Malay-language sources addressing mothering and motherhood within the optic of what was considered ‘advanced’, ‘backward’, and ‘healthy’ in the late 1800s and early 1900s, in both the metropole and periphery of empire. The concluding section pulls together the various threads unspun in the article to reflect on the semantic and methodological shift away from ‘modernity’ (as a Euro-American phenomenon) and towards ‘progress’ (as a potentially distinctly indigenous path into the future).

Hygienic modernity and women

In early twentieth-century writings by women in Java and Sumatra, the domestic sphere of the household was considered a space for agency and a broader affirmation of emancipation; what is more, certain elements of ‘tradition’ were seen as cornerstones of progress. A decade after the Perempoean Bergerak editorial quoted at the beginning of this article, in the pages of Isteri (‘Wife’)—the monthly magazine of the Alliance of Indonesian Women's Associations (PPII)—Ms Soeparto reflected on the 1930 Lahore Women's Congress she had just attended. After mentioning Turkey, Egypt, China, Japan, and India as examples of women's emancipation movements, she added:

Many old traditions [adat-adat koeno] have been thrown away, especially segregation [purdah], child marriage, the caste system … but will Asia copy Europe? Will it become Europe? Surely Asia has received much influence from the West, but this is not proof that Asia has reached westernization. Asia is not unwilling to learn from Europe, but inside it will stay like before. … Asia's civilization is only pulled by one great goal, the emancipation of eastern souls [kemerdekaan djiwa ketimoeran]. The progress [kemadjoean] of Asia means: Asia will be born again in another body, but inside it will remain the same.Footnote 33

Women's writing from this period interwove criticism of Westernization with the question of female (and national) emancipation, and the domestic realm was seen as a setting for action, not of repressive disciplining or mere supporting acts. The PPII Alliance had held its own congress in 1930, offering a platform for speeches covering such issues as girls’ education, health, the women's movement in Asia (as represented by the Lahore Women's Congress), and the reaffirmation of women's role as pillars of the household. And to be sure, challenges to Western models of progress in favour of ‘Eastern’ values resonated with most demographics. Perempoean Bergerak had listed religion as a pillar of its worldview in 1919; in 1940 the Sumatran Islamic modernist magazine Pedoman Masjarakat published a short story, ‘Contemporary Girl’, by the Acehnese author Ali Hasjmy.Footnote 34 The female protagonist, Leila, was a former ‘modern girl’ whom at this point in the story is wearing a headscarf and attending an Islamic school. Confronted by her neighbour's statement that the Western-style household was the hallmark of progress, the following exchange ensues:

LeilaBut we are people of the East

RoesliYour thinking is very narrow, Leila. We must follow those who have already advanced

LeilaBut the Japanese have never left their customary civilization [‘adat peradabannja], and they have already advanced

Leila does not succeed in getting Roesli to follow her reasoning, inspired by Japan,Footnote 35 that there could be an alternative to the opposition between tradition (indigenous ways) and Western modernity. Pressured by her parents—who hope that Roesli, a well-off intellectual and future doctor, would become their son-in-law—Leila eventually enters the Huishoudschool, a Dutch-styled girls’ school designed to advance hygienic and healthy practices; she takes off her headscarf and wears high heels; in her own future she sees living in a ‘beautiful house’ in the capital city, having a car, and being called Mrs Doctor.Footnote 36 Filled with stereotypes, this story illustrates the trajectory of ongoing conversations about ‘tradition’, ‘modernity’, and ‘advancement’, and their intersection with questions of hygiene, (religious) morality, and gender roles.

By the time of the Japanese invasion in 1942, Queen Wilhelmina's so-called Ethical Policy had been promoting preventive medicine and expanding the reach of European-styled education as tools of ‘uplift’, ‘civilization’, ‘modernization’, or ‘progress’ for 40 years. As Frances Gouda has suggested, though, Orientalist approaches remained. On the one hand, local elite boys were trained to become modernized insertions in the colonial administration, capable of interfacing with and performing within a European institution. Girls, on the other hand, were placed within an even more liminal space, as they were trained in sewing, cooking, and Western hygienic practices to prepare them for their ‘housewifely duties and maternal destinies’ in a ‘modern’ fashion, even as their education remained enshrined in ‘respec[t], if not celebrat[ion of], the distinctive character of Indonesian adat (customs and traditions) and indigenous religions’.Footnote 37 Yet, as the quotes above show, women were seeing beyond this duality of spheres. Before diving deeper into those sources, I lay out how women emerged as custodians and promoters of health within the project of hygienic modernity.

At the 1933 Pasar Gambir fair in Batavia, ‘the most attractive’ installation was the ‘Exhibition for Babies’.Footnote 38 Underscoring how useful it would be ‘for the Natives, with their very unhygienic conditions in the [native quarters] kampong’, the exhibit promoted hygienic practices, condemned superstition and the use of amulets, and promoted breastfeeding over ‘artificial feeding’ as an important step towards curbing infant mortality.Footnote 39 This was in line with decades-old assessments that poor hygienic conditions in the Indies did not allow bottle-feeding to be safely practised;Footnote 40 breastfeeding was then presented as the lesser evil, as beriberi (a disease caused by vitamin deficiency) was often identified as the cause of ill-health or death among breastfed infants and young children, due to their mothers’ lack of proper nutrition.Footnote 41

In that same year, the Office for Public Health Propaganda sponsored the publication of a series of illustrative plates to explain how health and hygiene were key to personal and societal success.Footnote 42 These plates, devised by Pierre Peverelli (more on him later), were meant to be hung in colonial schools for indigenous pupils, enshrining two pillars of the Ethical Policy, namely education and preventive medicine.Footnote 43 After decades of focusing their efforts on coercive medicine, the Dutch (mostly) side-lined forced vaccinations and quarantine-orders, and instead rolled out a novel two-fold approach: on the one hand was the creation of (or, rather, the pledge to createFootnote 44) sanitation infrastructures, from water pumps to wells and latrines. On the other hand, imbibed in the perception that colonized peoples did not know about the advantages of cleanliness, they began direct propaganda work to increase awareness, if not enthusiasm, about the importance of hygiene in fostering good health.

Perceiving the local population as ignorant, unwilling to ‘learn’, and suspicious of foreigners, colonialists’ sense of superiority of Western understanding of health and hygiene (notably only developed in the nineteenth century), which dismissed local practices around bathing, food preservation, and healing, was a crucial underpinning to the new hygiene campaigns of the Office of Health Propaganda.Footnote 45 Supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, small-scale projects were launched in Java in the 1920s that rolled out programmes aimed at educating portions of the population in personal, domestic, and environmental hygiene as practices fundamental to halting the spread of highly contagious diseases. In the tropics, such work mostly targeted skin diseases and water- and insect-transmitted infections like cholera, typhoid, and malaria.Footnote 46

Peverelli's illustrative plates mentioned above are set in an indigenous rural ‘native quarter’ (kampoeng) built along a river; children are seen wearing a mixture of Western and local clothing (but never shoes!Footnote 47), and the houses are made of rattan. ‘Health is a great treasure’ proclaims the first plate, further showing how whoever gets sick no longer enjoys the idyllic village life. Mosquitoes, flies, lice, and rats are singled out as the main culprits of many diseases, and prevention is identified as achievable through improved personal hygiene, consumption of uncontaminated foods, and careful sourcing of drinking water. The colonial administration had put the problem of contagious diseases and water contamination down to the Indies’ population's lack of modern sanitation. An article in the popular Dutch-language periodical Koloniale Studien described the liminal rural-urban kampoeng as ‘places filled with huts made of bamboo, wooden planks, and woven mats, with shutters but no windows, with no floors but earth, with no bathrooms, no washing place, and no water closets’.Footnote 48 Rudolph Mrázek describes this narrative as one filled with colonial ‘modern negatives’. But in fact, as already noted in the leftist, independent Malay-language periodical Doenia Bergerak ('World on the Move'), the increasing incidence of water-borne diseases that killed many, even during the dry season, was likely caused by the colonial authorities’ contamination of clean water with ‘artificial fertilizers containing sulfuric acid and highly concentrated phosphate’, rather than unhygienic practices in the kampoengs.Footnote 49

The plates had been conceived by Dr Pierre Peverelli, director of the Municipal Health Service of Batavia; he was a vocal Ethicist advocate of preventive medicine and ‘collaboration’ through education, with similar ideas to the Rockefeller Foundation. Peverelli's efforts were thus focused on teaching everyday practices of preventive medicine to Java's population. Well aware that there were not enough doctors,Footnote 50 he suggested that individual responsibility was a necessary complement to curative medicine and enforcing quarantine laws during emergencies. School children were his primary target: ‘We have to endeavour to teach the Bumiputera children … the children of the nation won't care about the laws and will do only as their own heart wants.’Footnote 51 Hence, he launched the establishment of the Health Brigades (Gezondheid Brigades) among European and Malay youth groups aimed at pursuing outreach activities to popularize science-based hygienic practices and discredit all indigenous forms of hygiene and healing practices. In addition, Peverelli was also a most prolific author of booklets for schoolteachers and laypersons. His core message was that being sick caused poverty, as it both disrupted all activities—work, school, household chores—and was expensive. ‘What is better than curing an illness? Not getting sick at all!’Footnote 52 His advice to the Indies’ middle classes (sometimes blurring the racial identities of his audience) ranged from maintaining a good posture and wearing shoes to eating a vitamin-rich diet, killing flies, and bathing ‘at least once a week’.Footnote 53

The move away from coercive curative medicine and towards education-based prevention had arrived in the colonies after important shifts in Europe. In the immediate aftermath of the discovery of bacteria by the German Robert Koch (1843–1910), Britain, Germany, and France each launched major public health initiatives.Footnote 54 The Dutch had been pioneers of cleanliness,Footnote 55 but they came late to the public health reform movement, only after the French and British authorities had already embraced a semi-official approach that placed ‘a kind of medical imperialism incorporating both the medicalization and moralization of society’ at the centre of official reforms.Footnote 56 This was not an exclusively European phenomenon, as Japan had also adopted a similar strategy.Footnote 57 The Meiji government established a Central Sanitary Board to tackle epidemics and ‘preserve the people's well-being throughout the nation’.Footnote 58 As pointed out by Ruth Rogaski, ‘eisei [hygiene] was a key link in the creation of a wealthy and powerful nation’, and Japan's sanitary movement extended to the rest of Northeast Asia as an important strategy of imperial expansion in the early twentieth century.Footnote 59 In China and Taiwan, ‘“Hygienic modernity” became a vehicle for the expression of [Japanese] power, fear, and hope in the region's complex informal and formal colonial settings.’Footnote 60 In the 1940s, Japan would extend this approach to Java as well.

European women had already been ‘enlisted’ by sanitary reformers by the late nineteenth century; as a contemporary put it, ‘Long before the word sanitation was heard of, or any other word that conveyed the idea of a science of health, the good, trained, thrifty housewife was a practical sanitary reformer.’Footnote 61 In Japan, eisei had become part of most girls’ education by the turn of the twentieth century. ‘Domestic matters’ were turned into ‘domestic management studies, the discipline of a corps of specialists’ with training provided by women in ‘childcare, nursing of the sick, and prevention of contagious disease [together with] [c]ooking instructions’. By the 1910s being a housewife was ‘a recognized professional identity’.Footnote 62

The discursive pivot embedded in the so-called Ethical Policy was presented as an effort to support ‘native uplift’, but it was really just another incarnation of the mission civilisatrice aimed at the assertion of colonial modernity and protection of colonial economic interests through control of colonized bodies. As summed up by Warwick Anderson in the context of the Philippines, the late colonial state was

disciplinary and benevolent, or progressive within limits … [and] modern rituals of hygiene were linked intimately to the making of potential citizens and their surveillance. Self-government of body, involving proper conduct and comportment, became a necessary precondition for political self-government or national sovereignty.Footnote 63

Although I do not intend to give undue importance to the Ethical Policy, its efforts towards propaganda and education popularized the language of hygiene and health as avenues to improvement. Think of the Dutch officer who in 1926 argued that the primary task of government-employed indigenous doctors who travelled from village to village was ‘to make the population understand that the government means nothing more by the hygiene measures than to create a basis on which the progress of human society in economic and spiritual terms is made possible’.Footnote 64 The Ethical Policy contributed to the shaping of a social and discursive environment in which educated colonized subjects—including women—came to participate, finding a space for intellectual agency over the meaning and forms of progress.

Returning to those illustrative plates, women are at the heart of most of the efforts showcased: while a man is shown as reading a book inside the home and a young boy is relaxing under a tree, a woman is seen in the background venturing out with a basket on her head; she might be going to the market, to forage, or to do laundry. Women are then shown washing clothes, taking water from the well for boiling before use in the kitchen (see Figure 5), and hand-milling the rice, which complemented other nutritious foods (such as eggs, tempeh, yam, corn, and peanuts) to provide a rich diet (see Figure 6). It is the mother who takes her baby to the doctor after the tuberculotic father (I assume) has coughed in its face.Footnote 65

Figure 5. ‘You can only trust pipe-water. Always boil water from wells and rivers.’ Source: Plate no. 13, in P. Peverelli and F. van Bemmel, Blyf Gezond! = Sehatlah Selaloe! (Groningen: Wolters, 1933).

Figure 6. ‘The danger of rice that is too white.’ Source: Plate no. 22, in Peverelli and van Bemmel, Blyf Gezond!.

It was women who cleaned the homes, kept mosquitoes and pests at bay, made sure everyone bathed (with soap if possible), and used boiled water in the kitchen. When shopping, women needed to be conscious about potential contamination of vegetables, meats, and milk (should they be able to afford such products); meals needed to be hygienically prepared and flies kept off the cooked food; and by 1930 fresh produce would be better kept in the refrigerator, should one own this ultimate symbol of gendered hygienic modernity.Footnote 66 Women, as wives and primarily as mothers, were at the forefront of this trajectory of progress,Footnote 67 but did not fully adopt European practices.

Motherhood in the colony

On the pages of the widely read Bintang Hindia, in 1928 women exhorted each other not to consume too much alcohol during pregnancy, and to be vigilant about hygiene and cleanliness

to keep the baby healthy. There are millions of bacteria everywhere … the care-giver who does not understand the importance of cleanliness and picks up a baby without washing their hands with soap is not fit for caring. Here in the tropics the baby needs to be washed with soap every day.Footnote 68

Writing in 1930, Sri Mangoensarkoro endorsed such Dutch practices as not picking up a crying child or not letting the children spend too much time with the servants, especially at night, because they could ‘pass on’ negative traits; she also vehemently discouraged excessive clothing—‘What's the point of putting socks on a little child? The less they wear, the better for them.’ Paying regular visits to the doctor also seemed unnecessary, as village children ‘are healthier than our [urban] children’ and evidently only ‘Mother Nature is their doctor’.Footnote 69 Clothing and doctors were both trademarks of colonial motherhood,Footnote 70 mostly as identifiers of European-ness and scientific modernity.

In 1931, a woman named Soekarmi argued that ‘women should know about nutrition’ to ensure a varied and balanced diet, and to consequently promote the good health of the household. After explaining the role of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, Soekarmi introduced vitamins as a ‘very new’ and ‘important’ field of scientific knowledge. Far from simply propagandizing advances in Western scientific research, Soekarmi turned this explanation of modern nutrition into an opportunity to validate how ‘the habits of our women in the villages, or of old-fashioned women, are not so wrong and are in fact most correct’. Feeding bananas to small children boosted their vitamin A intake; extended breastfeeding ensured the best nutrition possible; eating bran, common among people in the villages, limited the occurrence of beriberi disease; with their exposure to the sun, Indonesians did not need to be concerned with rickets. ‘Above all we know that in Indonesia we don't need to be afraid of vitamins’ deficiency.’Footnote 71

As hygiene had become a core principle of progress in Europe and Asia alike, scientific expertise reshaped paradigms of infant-care and -feeding in what Rima Apple has dubbed ‘modern motherhood’. This also became evident in Indonesia, where the discovery of vitamins and the influence of child-rearing advice produced by (and primarily intended for) Europeans seemed to challenge local practices. The Dutchman Christiaan Eijkman (1858–1930) made the connection between beriberi disease and the nutritional deficiency of polished rice while working in Batavia. Discovered by their absence, vitamins became another layer to the scientific construction of social progress. In many Asian locales,Footnote 72 as in Europe and North America, vitamin deficiency was the result of ‘too modern’ a diet that privileged polished rice and processed foods. In industrialized Euro-America, and among the middle- and upper-classes of both metropole and periphery, the solution was seen in vitamin-enriched foods.Footnote 73 But voices from Java and Sumatra offered a different perspective, arguing that the customary indigenous diet of the kampoeng was in fact ‘most correct’ according to the standards of modern nutrition, as it prevented this major debilitating disease.

Women like Sri Mangoensarkoro and Soekarmi actively engaged with concepts and practices of health, hygiene, nutrition, and ‘progress’. But instead of embracing wholesale what Dutch models of colonial modernity had to offer, these educated middle-class women aspired to adapt to the changing times by straddling across and negotiating between identities and strategies. While certain European innovations were generally adopted—such as rules of cleanliness,Footnote 74 despite the recognition of the paternalistic tone of some Dutch punditsFootnote 75—many other were questioned, criticized, or emended. In the next two sections I explore Dutch colonial views of European and ‘native’ mothering through sources from Java, Sumatra, and South Sulawesi, and voices in the vernacular Malay to contrast the differing approaches to and narratives about infant care and feeding.

Dutch mothering

At the end of 1931, the Association of Housewives in the Indies began publishing its newsletter in Batavia, De Huisvrouw in Indië; shortly afterwards, several local branches of the association also started printing their own periodicals. On the very first page of its first issue, Nestlé placed a full-page advertisement reproducing a clipping from De Indische Courant reporting news that the police had filed a report about a local milk distributor diluting milk with water from a ditch. ‘It could have been YOUR milk! Only buy reliable milk—use milk products from Nestlé’.Footnote 76 Several milk companies had existed in Java and Sumatra since the late 1800s, but the local dairy industry had struggled to find ways to guarantee enough supply and hygienic processes in this tropical colony, despite known advances in other countries. The dangers of tempering, spoiling, or contamination made it a risky business.Footnote 77

Throughout the nineteenth century colonial doctors had encouraged breastfeeding of infants (Dutch and Eurasians) in their home remedies’ manuals.Footnote 78 Yet, as milk was a staple of the colonial diet, products such as powdered and condensed milk had quickly become popular. Commonly advertised in Dutch, Malay, and several regional languages in Java and Sumatra, Omnia from the Netherlands, Glaxo from New Zealand, and Nestlé's Lactogen and Milk Maid products from Switzerland were all available and actively promoted.Footnote 79 Developed to feed soldiers and cure the debilitated during various wars in North America and Europe, milk products were also marketed in industrialized England as a cheap and long-lasting infant food substitute for the rapidly growing group of working-class mothers who could not afford to stay home and breastfeed. The following incarnation for milk substitutes was to enable middle- and upper-class women to perform modern motherhood through practices of physical separation of mothers and babies, self-reliance, and self-soothing, allowing mothers to be freed from the burden of infant-care; oftentimes, this was also to restore their bodies (and especially their breasts) to sexualized expectations of femininity. Despite the fact that doctors expressed concerns over the low nutritional value of condensed milk early on, this trend was couched in science and medical advice. Similarly, upper-class habits such as separation of child and adult, feeding on a schedule, and the mandate to not comfort an unsettled baby came to be presented as having a medical and hygienic rationale behind them.Footnote 80

By the turn of the twentieth century the Indies were no longer the exclusive destination of sailors and soldiers. As private entrepreneurs, single women in search of a husband, and entire families moved to the colonies, young Dutch women of marriageable age (and mothers to-be) took these expectations with them.Footnote 81 Motherhood became part of the imperialist project in the Indies, and with more European-born women moving there ‘mothering [by Dutch women] was now a full-time occupation of vigilant supervision of a moral environment … [with] prescriptions for proper parenting detail[ing] the domestic protocols for infant and childcare with regard to food, dress, sleep and play’.Footnote 82 In this context medical advice, colonial discourses, and social desires intertwined and clashed.

In Holland most middle-class women would have hired wet-nurses, satisfying the demands of doctors and society alike, but in the colony this option had to be set aside on racial considerations, further expanding the market for milk substitutes.Footnote 83 As argued by Ann Stoler, indigenous servants had become a potential source of ‘contamination’;Footnote 84 echoing ancient Roman beliefs reaffirmed again in sixteenth-century England—according to which personal characteristics could be transmitted through breastfeeding—Dutch children in the Indies were said to need protection from the ‘extremely pernicious’ moral influence of ‘babus’, the nursemaids who might otherwise have cared for them.Footnote 85 Local women were deemed unfit to raise European children.Footnote 86 Both hygiene and infant care were tightly intertwined with morality, and women, as mothers, were at the forefront of the colonial effort to maintain racial boundaries (and thus European rule) through moral and cultural practices. As Jean Taylor also points out, after the British interlude in Java, Dutch patterns of rule and sociability changed; previous practices of racial mixing with local Eurasian women from influential families were rejected, and an effort to maintain racial, cultural, and moral homogeneity with the motherland was embraced instead.Footnote 87 Young women were trained to be housewives, and

advice manuals prepared women for the task of maintaining a ‘proper’ Dutch home in the East. In them the link between personal habits and morality was made explicit. Sections were devoted to hygiene practices for preserving the health and energy of family members in the tropics, the necessity of avoiding certain foods, and other precautions to preserve moral character.Footnote 88

Thus, first condensed milk and later patent infant foods became common fare among the Indies’ Europeans, as they rejected both breastfeeding and wet-nursing on medical, racial, and moral grounds. This additional barrier specific to the colony made Dutch government efforts futile and fuelled instead the market for milk substitutes. The Indies’ Dutch-language press had publicized scientific discoveries from Europe proving ‘the great value of breastfeeding’ beginning in the early 1900s;Footnote 89 and in the mid-1910s and 1920s, news was regularly broadcast about the success of moeder-cursussen and consultatie-bureaux tasked with supporting new mothers in eating well, staying clean, and breastfeeding their babies in regions of the Netherlands with high mortality rates.Footnote 90 Yet it is clear that in the 1930s, Dutch colonial society in the Indies rejected breastfeeding. In the mid-1920s there were scores of advertisements marketing Ovomaltine and Quaker Oats as helping breastfeeding mothers produce more milk,Footnote 91 but by 1931–1932 the only advertisements that mentioned breastfeeding were its substitutes, Glaxo and Lactogen.Footnote 92 In the colonial press, the presence of two doctors was alternated, one stipulating that ‘Breastfeeding is best’, the other presenting all possible alternatives to it, and their advantages.Footnote 93 The popular magazine Marriage and Household, in its third issue of 1932, included an article on bottle-feeding;Footnote 94 in 1934, the Housewives's fair showcased and distributed instructions for bottle-feeding.Footnote 95

The Orientalist gaze

Dutch approaches to infant-care in the Indies took shape by being modelled on European examples, but also in express opposition to what they saw practised by the local population. Dutch medical officers, the wives of Dutch preachers, and writers of popular books labelled local practices that countered European modes of modern motherhood as inferior and uncivilized. Prominent among these were breastfeeding on-demand, having babies sleep in the same room as their mothers, and keeping infants and toddlers in slings.

In his 1830 History of Java, Thomas Stamford Raffles had stated that ‘women of all classes suckle their children’.Footnote 96 And subsequent observers continued to notice that women across the archipelago carried their babies in the slendang (a shawl used as a baby sling), and were prone to respond to any calls from baby with the breast, leading native babies to then be seen as overfed and overly-dependent.Footnote 97 At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Dutch physician Kohlbrugge (1865–1941) had argued that ‘the constant giving of the breast’ translated in the inability of the ‘natives’ to control impulses.Footnote 98 A book published in Medan, North Sumatra, for an audience of plantation-managers’ wives, advised women to feed their babies on a schedule and to keep them either in a baby-carriage or a play-pen, openly criticizing indigenous mothers for ‘overfeeding’ their babies as they constantly had them at the breast,Footnote 99 carrying them in the slendang.Footnote 100 In 1929, the government-sponsored organization Twee Kruisen (Two Crosses) set out to train midwives and build hospitals for ‘modern birthing’ and to teach ‘modern upbringing’ techniques to ‘the backward natives’.Footnote 101 A similar approach was still embraced by the wife of a Dutch pastor in the mid-1930s in South-East Sulawesi. As she led regular moeder cursussen for women in the area, her ‘Dutch course’ dedicated an entire chapter to ‘the particulars of bottle-feeding, children's flours, etc.’ but the topic of artificial nutrition was expressly omitted in the course for local women as ‘all mothers here feed their children themselves’.Footnote 102 As shown in Figure 4 above, in the late 1930s Indies’ women's breastfeeding habits were still exoticized. In 1961, Hildred Geertz argued that swaddling, carrying, and extensive feeding of infants in Java encouraged passivity, a view reaffirmed in the late 1970s by James Peacock.Footnote 103

Marketers, who had been taking full advantage of the burgeoning vernacular press and gradual emergence of a local middle class, also took advantage of the colonial discourse that breastfeeding was backward. In the Indies, milk substitutes were portrayed as a Western innovation and became an aspect of a modern lifestyle in which local women could also partake. ‘Who says the native is backward?’ ran a 1926 Dutch-language advertisement for Lactogen, by the Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Co., showing a Javanese woman dressed in a sarong-kebaya, bottle-feeding an infant while sitting on a rocking chair (see Figure 1).Footnote 104 The following year, Lactogen dominated the infant-care stall at Bandung's hygiene exhibition (EHTINI), with claims about hygiene and health, and the slogan—in Dutch—‘Lactogen, for your baby’.Footnote 105

Indigenous mothering

As observed by the Europeans, mothers in Java, Sumatra, and other islands tended to breastfeed on demand for many months, if not years. A Javanese text composed in 1907, illustrating various rituals and life-cycle events, noted that babies should be breastfed for over a year, with boys being weaned at 16 months of age, and girls at 18 months.Footnote 106 But if Dutch women, conservative colonial officers, and marketers portrayed indigenous practices of breastfeeding as backward, the representatives of the Ethical Policy saw its hygienic advantages. The profusion of government-sponsored publications, in Malay and several local languages, warning against the dangers of bottle-feeding indicates that other forms of feeding were common, and as commonly ill-practised due to the lack of clean water and correctly formulated substitutes.Footnote 107

In 1919, the publication of the bilingual booklet Caring for Baby had been spurred by concerns over high infant mortality.Footnote 108 While it emphasized the need to feed ‘on a schedule’, indicating the specific duration of suckling times and intervals,Footnote 109 the book also stressed that mother's milk was the healthiest option for the baby.Footnote 110 The intended audience of this and similar publications were the local lower classes, uneducated and employed in jobs from the lowest rungs of the social ladder. Parents were bestowed with the duty to reduce babies’ chances of death, a goal which could be achieved only by eradicating ‘stupidity and dirt’ and by ensuring that the mother didn't ‘stop breastfeeding the baby without a reason, then giving baby artificial food’;Footnote 111 this echoed European trends that blamed working-class mothers’ ignorance and negligence for their infants’ deaths.Footnote 112 The Malay translation also added that ‘mother's milk is the best food for babies … by custom’ (kepada ‘adat), making it an element of women's own cultural heritage.Footnote 113 On the other hand, ‘lesser-quality or counterfeit milk, contaminated milk’,Footnote 114 and anything that was not breastmilk, was identified as a common source of illness for babies, leading to the condemnation that ‘bottle-feeding, whether with cow milk or tinned milk, is a very dangerous evil’. The ‘evils’ of bottle-feeding, from bacteria to excessive sugar, seemed impossible to avoid, and more space was dedicated to discouraging its practice than to its proper domestic preparation. In 1922 this gap was filled by A Guide to Teach School-Children about Infant Care, a compilation of simple instructions for young children left in charge of their even younger siblings. Again, its audience was working-class families, as mothers were ‘working, or cooking in the kitchen, or if she has gone to the market, or with your father to work in the rice fields, you, oh elder daughter, must care for your young sibling!’.Footnote 115 The author gave absolute priority to the avoidance of ‘little bugs’, mosquitos, and flies, reaffirming the importance given to hygiene and cleanliness as functions of good health. Amid all these instructions, the best course of action to ensure the good health of infants was still indicated to be mother's milk taken directly from the breast.Footnote 116

While periodicals’ editors and contributors exposed the shortcomings of milk substitutes, advertisements continued to capture a share of the market. A common brand was Milk Maid sweetened condensed milk, known locally as Soesoe Tjap Nonna. This was not only advertised in newspapers and women's magazines, but—ironically—it made its way onto the back-cover of government-sponsored books about infant care, such as reprints of the already mentioned Caring for Baby and A Guide to Teach School-Children about Infant Care. Marketed as ‘the best milk for babies to drink; strengthening and healing their bodies’, Soesoe Tjap Nonna was announced as the choice of several mothers of ‘many of the native babies’ admitted to a baby show. At the same time, it was also ‘available in all shops’, thus translating the perceived exclusive access granted to the urbanized upper class who participated in baby shows as a potential reality for all mothers and infants.Footnote 117 But the publisher, the government agency Balai Poestaka, also included an insert on milk originally published in 1931 in its own Malay-language periodical Pandji Poestaka. The insert, a translation of an article in German, addressed the shortcomings of both cow's milk and tinned milk as infant-foods and, without mincing words, it called individuals who fed their babies sweetened condensed milk ‘stupid’ because it lacked the most-important vitamin content of milk. The preface penned by Pandji Poestaka was an honest acknowledgement of the conditions of the urbanized population and the power of advertising that marginalized indigenous practices.

Us boemipoetra [sons of the soil], we feel strongly that our infants ought to be fed by their own mothers’ breasts. Because in that breastmilk there is all the nutrient that is needed by the baby; needed, so that their body is healthy, so that their body grows as necessary; needed, because if the body of that baby is too weak, surely it will fall ill.

But in fact, in the long run, increasing numbers of urban settlers, even boemipoetra mothers, feed their babies tinned milk, which is so well-praised in advertisements etc.

These boemipoetra continue to increase their numbers. This is why we felt it appropriate to clip this article.

The process of colonization had initiated major social, economic, and environmental changes, leading to urbanization (and subsequent degradation of the environment and pollution of food sources), employment of women outside the home and away from their children, and the import of foreign goods that projected an aura of ‘modernity’. The Ethicist spirit purported to solve these problems without acknowledging that they had originated in colonial intervention and presenting solutions that had previously been the norm. Rejecting the framework of ‘natives’ backwardness’, educated middle- and upper-class women in Java and Sumatra refocused attention on the fact that some ‘traditional’ indigenous practices fitted the discursive bill of hygienic modernity.

Tradition as progress

Formula and condensed milk companies might have projected an image of milk substitutes as products that mediated an attainable Western-styled modernity, but in Java and Sumatra many of the middle- and upper-class women who engaged in the conversations over ‘progress’ eschewed the symbolic status granted by bottle-feeding. They focused on the nutritional advantages and the more easily manageable hygienic profile of breastfeeding as real pillars of a ‘healthy progress’. Breastfeeding was not only ‘traditional’ or an advantageous expedient for lower class mothers who could not afford expensive patented infant food or did not have access to clean water; it was outright the best option.

Anna Sjarif—the Dutch-educated editor of the women's page of Bintang Hindia, a government-supported Ethicist Malay-language periodical—echoed Dutch criticism of answering every cry of a baby with the breast, so that ‘what often happens is that it is given too much food’. But she was also clear that it was not right if young women who could speak French, German, and English; could play the piano and tennis; and who were well-read in literature ‘had no idea how to care for a baby’ and how to nurse.Footnote 118

Writing by women from Java and Sumatra intersected with, but also complemented, colonial Ethicist approaches to caring for indigenous babies. In 1931, in a long article dedicated to ‘Mother and Child’ and penned by Iboe (lit. ‘mother’ in Malay), breastmilk was described as ‘God's wealth, [as] mother now contains the food needed to satisfy the hunger and thirst of her baby, so to give him strength for life’; indeed, ‘if possible, baby should not be given any other food besides mother's milk, because other milk, no matter how good it might be, cannot match the mother's own milk’. Whereas the author also suggested that a mother should consult a doctor for supplementation should she not be able to feed the baby ‘because of illness of insufficient quantities’, there was no kindness for the mother ‘who does not like to nurse her baby even if she does have enough milk, woe is the mother who has such thoughts!’ Drinking one's own mother's milk was a ‘right given to us by God’.Footnote 119 Similar advice circulated in Sumatra. In an article published on Soeara Iboe, the local women's magazine in Sibolga-Tapanuli, on the West coast of Sumatra, the (unnamed) author divided her attention between the imperative of cleanliness—meaning regular soapy baths and clothes changes—and feeding baby the healthiest diet, namely mother's milk.

New-borns and infants ought to nurse from their mothers. ‘Tradition’ under the guise of religion was lending support to an argument based on nutrition.Footnote 120 It was that same year that Soekarmi had concluded that village eating habits were validated by the discovery of vitamins, and that breastfeeding was the best option for mothers and babies.Footnote 121 Dutch doctors had been concerned about the implications of beriberi for breastfed infants, but ultimately the data showed that breastfeeding was indeed the best option. In 1941 the three foremost Dutch paediatricians in the colony published a paper on xeropthalmia among Batavia's infants: only 11 per cent of the admitted infants under one year of age had been exclusively breastfed, indicating to them that breast-fed infants did better than their peers.Footnote 122

The women offering this advice were representative of the educated upper- and middle-classes. They owned watches and had access to scales; they had separate beds and (possibly) separate rooms for their babies. Obviously, they would have had access to clean water and been able to feed milk substitutes to their babies in a safe and accurate manner, should they have chosen to do so. As explained by Iboe, their babies needed to be fed for only about 15 to 20 minutes, seven times a day at regular intervals, and with a night-time break between midnight and 6 am, during which time the baby was supposed to sleep through, on its own mat, separate from its mother. Before and after each feeding the baby's mouth and mother's nipples would be cleaned with boiled water to avoid any disease,Footnote 123 and in order to be sure that ‘baby is drinking well and enough’ mothers weighed their babies before and after every feeding.Footnote 124

Advertisements marketing breast-milk substitutes projected a European modernity and ‘healthfulness’ that lower class women could not afford and the elite didn't want. Bottle-feeding was discouraged by and for those who could have bought the expensive patent formulas and knew about (and could afford) sterile bottles and boiling water. Literate women in Java and Sumatra, writing for their peers and possibly beyond through community reading and word-of-mouth, condemned the shortcomings of breast-milk substitutes and elevated breastfeeding to the preferred option. They followed Western ‘modern’ rearing and feeding scheduling practices most diligently, to the full extent of their capabilities, but they deliberately chose to breastfeed their babies. Other forms of feeding were not contemplated as an option for the diligent, healthy, and therefore advanced (madjoe) mother.

Conclusion: From modernity to progress

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Dutch colonial administration embarked on a new embodiment of the civilizing mission (i.e. the Ethical Policy) that promoted ‘native uplift’ through at least two new avenues: education and hygiene. The expansion of educational opportunities, limited as it was, also touched women, facilitating their participation in public debates on the pages of an expanding vernacular press. Similarly, the embrace of hygienism and nutritionism resulted in the emergence of women as the primary drivers of progress through their traditional roles in the household. These shifts did not go unnoticed, and marketers began to interface with the rising indigenous middle class as a new consumer base potentially aspiring to achieve ‘modernity’ through consumption, as already suggested by Hoogervorst and Schulte-Nordholt. Among the many products made available, one category is of particular interest because of its connections to the new framework of hygienic modernity and its intersection with women's ‘traditional’ roles and practices of motherhood: milk substitutes for infants.

As seen throughout this article, all these elements combined together brought local women to frame an aspect of ‘tradition’—breastfeeding—as madjoe. Indonesian women's performativity as mothers was neither a direct imitation nor a rejection of foreign practices advertised and promoted as ‘modern’. Rather, health-driven progress took shape as a negotiation between scientific paradigms and local sources of knowledge. Reading deeper in the sources, amid the political developments in Java and Sumatra at a time when the anti-colonial movement was gaining strength, I propose that the criticism of bottle-feeding by educated middle- and upper-class women in Java and Sumatra was a conscious (sadar) rejection of Dutch racial projects of control of colonized women's bodies, and their way to affirm ‘native superiority’ through promoting breastfeeding.Footnote 125 Colonialists’ calls for indigenous women to breastfeed were made on the grounds of their assumed inability to keep artificial feeding hygienic (mirroring similar condemnations of working class mothers in the metropole), but colonized women made a more nuanced argument, in which the problem was not access to clean water and bottles or to well-designed formulas. Milk substitutes were lesser than breastfeeding because of their potential to be harmful. The superiority of breastfeeding (denigrated as ‘primitive’ by European observers) was asserted on the grounds of scientific discoveries and medical opinions, which confirmed the nutritional value of breastfeeding versus the inadequacy of its substitutes, despite the projection of bottle-feeding as ‘modern’ through advertisements and Dutch women's practices in the colony. Appropriating the essence of the meaning of ‘modernity’ as ‘healthy’ and ‘hygienic’, and framing their own goal as ‘progress’, as expressed in 1919 by the editors of Perempoean Bergerak, these women shaped a singular framework of kemadjoean centred on understandings and perceptions of healthfulness that I have named ‘healthy progress’.

The concepts of progress and advancement embody and invoke movement. I am not referring to the teleological views of modernization theories, rather to the concept of progress as fluid transformation. This is particularly apt to the case of Indonesia, where kemadjoean (as progress) and pergerakan (as movement) were keywords commonly used by writers and activists during the colonial period. Takashi Shiraishi pioneered the study of the pergerakan as political mobilization of the anti-colonial independence movement. In this case, the only telos was self-rule, which could have taken the form of a European-styled republic, a Soviet-styled council, or an Islamic state. Susan Blackburn, among others, has deployed the same frame of ‘forward movement’ in her analysis of women's organizations, where the primary goal was female emancipation (lit. kemadjoean perempoean),Footnote 126 whether according to Euro-American standards, Islamic scriptures, or ‘Eastern values’. Notably, women were not beholders of traditions to counterbalance male embodiments of modernity. Rather, they were most engaged—through writing and action—in negotiating between and across multiple ideals of progress. A 1940 advertisement for the national railways, printed in Pandji Poestaka, represented a standard image of ‘modern, middle-class Indonesian consumption’;Footnote 127 trains ‘were used as a prominent symbol of modern times’. And as the man of the family approaching the train was dressed in a suit-and-tie, the boy in shorts and a sailor's hat, the baboe in a kebaya-sarong—each indicating their status through stereotyped appearances—the mother was clad in a sarong, walked in heels, and had her baby in a slendang.Footnote 128 Already in 1912, Raden Ajeng Soematrie (sister of the better-known Raden Ajeng Kartini) had noted how ‘Young Native households with young wives at their head, contribute unselfconsciously to the progress of their people through the new atmosphere which they have brought into the native environment;’ this included a ‘regent's wife who carried her own baby in a slendang … [on] a train’.Footnote 129

Jettisoning ‘modernity’ and embracing ‘progress’ allows the avoidance of superimposing the pre-assigned analytical valence and bias of the term, which would dislodge the many nuances and referents intended instead by the sources. Malay-language sources allow this epistemological shift: ‘modernity’ (kemoderenan) and ‘modern’ things refer specifically to European post-Enlightenment ideals of societal advancement. Rather than assuming identifiable moments of rupture with the past (which creates the dichotomous and ever-shifting relationship between ‘modernity’ and ‘tradition’), the sense of movement enshrined in the idea of ‘progress’ projects a fluid process that can make turns, adapt to changing conditions, or—as I argue here—invoke the standards of Western modernity to make of ‘tradition’ (or, indigenous ways of knowing) a stepping stone on the path forward.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was conducted during a fellowship at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV), Leiden; thanks are also due to the College of Arts and Science, Cornell University, for their financial support. This article was first drafted during a fellowship at the Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore. My deepest gratitude goes to my students as well as my colleagues, who engaged in invaluable conversation (or even read drafts) as I developed the ideas herein discussed. Special thanks, in alphabetical order, to: Louise Edwards, Tom Hoogervorst, Hans Pols, Henk Schulte-Nordholt, Naoko Shimazu, Yun Zhang, and Taomo Zhou. The anonymous reviewers of MAS offered extremely constructive feedback, effectively improving both the form and strength of the argument. All mistakes remain mine.

Competing interests

None.