A. Introduction

Democratic systems of public administration constrain regulators’ use of public authority by various rules, procedures, and institutions. Regulators must act within their powers and they may need a specific authorization to act. They may be obliged to conduct consultations and assess their actions’ costs and benefits prior to taking the action. Their actions may be challenged before a court, and so on. In the European Union (EU), the legal and constitutional framework for administrative rulemaking has struggled to keep up with the growing role of the European Commission and Union agencies in implementing EU law, much of which takes place through informal acts known as soft law. Lacking formal binding force, soft law must meet few of the mandatory formalities that apply to normal rulemaking despite having many practical and potentially legal effects.Footnote 1 Due to its speed and malleability, soft law is an indispensable instrument of flexible governance.Footnote 2 At the same time, soft law powers give rise to legitimacy problems, particularly if they are overused or abused, which is why many have called for better procedural and judicial control of soft rulemaking.Footnote 3

This article adopts a broader governance perspective to soft rulemaking by investigating the complex ways in which regulatory innovation and the use of soft law by the European Supervisory Authorities (ESA) interact with procedural formalism and the scope and intensity of judicial review. Like all EU soft law, the ESAs’ guidelines, recommendations, opinions, statements and the like, straddle the margins of public law by design, occupying an elusive space that exists partly, and sometimes entirely, outside the legal boundaries governing the use of formal public authority. This space of shadow rulemaking, as it is called here, does not exist independently of the institutional environment in which the regulatory organizations operate. On the contrary, its shape and size are determined by it.Footnote 4 The resulting dynamics shapes the form and substance of regulatory innovations. They may arise as new solutions to new problems,Footnote 5 and thus represent tokens “of a maturing regulatory system,”Footnote 6, but they may also be motivated by more strategic behavior or even “creative compliance.”Footnote 7

Against such premises, this article addresses a pragmatic issue of governance: what type of procedural controls—ex ante—and review mechanisms—ex post—best facilitate beneficial forms of regulatory innovation while also controlling its excesses.Footnote 8

The article begins by showing how the founding regulations of the ESAs, as well as their predecessors, have both facilitated and absorbed regulatory innovations. Part B discusses in more detail two types of ESA instruments, “Q&As” and “no action letters,” which the 2019 reform of the ESA regulations added to the ESAs’ permanent regulatory toolbox.Footnote 9 Invented by the ESAs in the course of their supervisory practices, the instruments provide good examples of the ESAs’ demand-lead regulatory innovation. The section will also show that procedural control of the ESAs’ soft law competences has tightened gradually but steadily.

Part C presents and weighs an argument against procedural control of soft law less discussed in Europe. A popular argument in the United States has held that efforts at imposing rulemaking on a record may have the double impact of “ossifying” rulemaking and dislocating it to even less formal instruments, thus giving rise to a more complex and dysfunctional rulebook.Footnote 10 Subjecting administrative rulemaking to procedural formalism could thus perversely increase “governmental lawlessness.”Footnote 11 The article finds that such risks currently seem small in Europe, particularly considering the near-zero risk of judicial intervention. Without effective ex post review, even mandatory procedures would have little effect simply because it is nobody’s job to enforce them. After brief assessment of U.S. experiences with formal and informal rulemaking, the article argues for preserving regulatory flexibility and against over-proceduralization based on unpredictable and judicially imposed standards.

The final part—Part D—of the article assesses the ability of soft law acts to bypass not only burdensome administrative procedures, such as cost-benefit analyses, but also legislative procedures.Footnote 12 The adoption by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) of “no action” statements in 2017 and 2018 provide a good example of a regulatory innovation that, while responding to an urgent and unforeseen market need, also appeared to exceed the powers conferred on the agency. To effectively guard against such risks, and to ensure that soft law instruments maintain their “derivative” character, the EU needs a more functional framework of judicial review. The present remedies, whether judicial or administrative, do not match the growing importance of ESA soft law, particularly guidelines and recommendations. Nascent case law suggests that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) might be taking a less deferential approach to reviewing the legality of ESA soft law acts. This development should be welcomed.

B. The ESA’s as Rulemakers and Innovators

I. The ESAs’ Regulatory Powers

Installed at the apex of the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS) in 2010, the ESAs represented a new generation of EU agency. Their founding regulationsFootnote 13 emphasized the agencies’ independence and gave them a strong institutional role in regulatory governance. The majority of the ESAs’ regulatory work consists of developing and proposing binding technical standards, which the Commission endorses as directly applicable regulations following Articles 290 and 291 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). These standards, particularly the so-called Regulatory Technical Standards, have gained a primary position in the administrative governance of the EU financial market.Footnote 14 Important as these regulations are, they are notably technical in character, and they cannot entail strategic decisions or policy choices.Footnote 15 The ESAs do not have the power to adopt generally applicable binding rules by themselves. Article 9 (5) of the ESA Regulations provides the only exception, empowering the ESAs to adopt certain types of executive decision, which are hierarchically supreme vis-à-vis national authorities, and which may even have limited general effects.Footnote 16 Even such limited powers tested the Union’s constitutional limits to delegation of powers.Footnote 17

The existing constitutional safeguards against delegation have been toothless in the face of—and indeed probably complicit to—expanding governance by informal soft law instruments. The most important of the ESAs’ soft law instruments is guidelines. The ESAs’ predecessors, so-called Lamfalussy committees,Footnote 18 started to issue guidelines in the early 2000s, though their founding decisions were silent on any regulatory powers, soft or hard.Footnote 19 The Committees’ founding acts were updated only in 2009 to recognize their power to issue non-binding guidelines and recommendations.Footnote 20 In the following year, the ESA Regulations upgraded the regulatory status of guidelines and recommendations more significantly. Article 16 now provides that the ESAs may issue guidelines and recommendations addressed to competent authorities or financial market participants, adding that the addressees should make every effort to comply with them. To increase the bite of these instruments, national authorities are required to confirm within two months of the act’s issuance whether they comply or intend to comply with the act. The ESAs can also publicize non-compliance of national authorities, along with their stated reasons. Market participants have to report on their compliance only if the relevant act so requires. Just like all other “acts of general nature,” the ESAs adopt guidelines and recommendations following rules on qualified majority voting.Footnote 21

The ESAs’ ability to issue guidelines and recommendations, backed by Article 16 “comply or explain” mechanism, is the closest thing to genuine rulemaking powers at the ESAs’ disposal. Indeed, member states comply with the ESA guidelines with few exceptions. Based on ESMA’s compliance table, national authorities have notified non-compliance in only thirty-one individual cases, which suggests a compliance rate of approximately ninety-eight percent.Footnote 22 Of these non-compliances, few have been motivated by material dissent, but rather are explained by specific circumstances, which have made compliance impossible or difficult.Footnote 23 The European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines are almost equally effective.Footnote 24

II. Article 29 Instruments

Beyond guidelines and recommendations there exists a universe of soft law acts, which the ESAs have launched to promote supervisory convergence. Article 29 (2) of the ESA Regulations provides that the ESAs may promote common supervisory approaches and practices by developing new practical instruments and convergence tools. The 2019 ESA reform continued and solidified this innovation-friendly approach.Footnote 25 Based on Article 29, a wide range of soft law instruments such as “principles,” “public statements,” “statements,” and “Q&As” have seen the light of day.Footnote 26 Just as guidelines and recommendations, which were originally invented by the Lamfalussy Committees and subsequently recognized by their founding decisions, the 2019 ESA reform added two successful Article 29 instruments to the ESAs’ permanent regulatory toolbox: “Q&As” and “no action letters.” The next section discusses these instruments, and the context in which they arose, more closely.

III. Q&As and No Action Letters

Since the launch of the ESAs in 2011, the Q&A process has become the most common and flexible way for the ESAs to communicate with market participants and with national competent authorities on matters of interpretation of common rules. The Q&A process, unlike Article 16 guidelines and recommendations, is not subject to “comply or explain” but it has increasing practical significance. As the EBA notes, peer pressure and market discipline “play a driving force in ensuring adherence to and compliance with the answers provided in the Q&A process.”Footnote 27 ESMA’s Q&A documents, periodically issued collections of questions and answers, complement every important piece of EU securities markets legislation.Footnote 28 The oldest Q&A still “in force” was issued by the CESR in 2007.Footnote 29 The EBA’s website lists more than 2000 individual questions for which an answer has been provided.Footnote 30 The 2019 ESA reform also introduced a new article specifically addressing the Q&A procedure.

No action letters are a more recent regulatory innovation that addressed more specific and immediate market demands. Unlike guidelines, recommendations and Q&As, which offer practical guidance on how to apply and interpret rules correctly, the purpose of no action letters is to address exceptional circumstances that call for non-application of rules. Ideally, the powers would be used to signal to relevant regulated firms that the full enforcement of applicable rules is temporarily lifted or postponed. Such “forbearance powers” are used extensively in the United States.Footnote 31 In Europe, the need for forbearance arose in early 2017 when financial market participants reported difficulties in meeting the deadline for margining rules for uncleared OTC derivatives under the European Market Infrastructure Regulation 648/2012 (EMIR). In a joint and short response, the three ESAs noted that they did not have general forbearance powers and that any delay would have to be implemented through a formal EU legal action. As this was neither possible nor desirable at the time, the ESAs released a joint statement informing the public of their expectation that national competent authorities would consider the specific circumstances and the needs of smaller firms when applying their risk-based supervisory powers.Footnote 32 Similar concerns materialized in the following year regarding other derivatives rules, which prompted another joint statement.Footnote 33

ESMA went much further in its two solo-issued no action letters. The action was again prompted by unforeseen market needs. First, it became apparent that European investment firms, trading venues, and their offshore clients were not ready to acquire a so-called “Legal Entity Identifier,” or LEI code, in the time specified in Directive 2014/65 (MiFID II) and Regulation 600/2014 (MiFIR).Footnote 34 In a statement issued in December 2017—and without any discussion of legal issues—ESMA set forth a transitional regime “to support the smooth introduction of the LEI requirements.” In practice, ESMA stated it would allow for a temporary period of six months during which the relevant firms could continue to service their clients using alternative compliance arrangements.Footnote 35 In 2018, the foreseeable delay in finalizing the review of EMIR legislation risked triggering costly consequences in relation to the expiration of certain temporary derogations. To avoid these costs ESMA released another statement, informing the market that it “expects competent authorities not to prioritize their supervisory actions” towards certain entities benefiting from the derogations.Footnote 36

Q&As and no action letters are good examples of the type of flexibility that Article 29 of the ESA Regulations facilitates. Both instruments, serving distinct regulatory needs, were also recognized and formalized in the 2019 ESA Reform. As the number and importance of ESA soft law has grown, however, so have concerns over their legitimation and accountability.

IV. Proceduralization of ESA Rulemaking

The procedural control of agency rulemaking in the EU has a notably asymmetric character. Whereas participation of Union agencies in the development of binding rules is subject to strict procedures, regulation by soft law remains informal and undisciplined.Footnote 37 The ESAs are no exception. The 2010 ESA Regulations set strict procedural rules and accountability standards for the development and adoption of binding technical standards. Articles 10 and 15 require that ESAs must, as a rule, always conduct open public consultations as well as cost-benefit analyses before submitting draft rules to the Commission and they must also request the advice of the relevant ESA stakeholder group.Footnote 38 Several provisions ensure that the European Parliament and the Council stay informed during the process and they also have the power to revoke the delegation of powers at any time. In the case of regulatory technical standards—adopted as delegated acts under 290 TFEU and thus capable of altering legislative text—the European Parliament and the Council may also object to the draft regulatory technical standards, thus preventing their entering into force.

The procedural control of the ESAs’ soft rulemaking has developed more gradually. The Commission decisions setting up the Lamfalussy Committees— the ESAs’ predecessors—set no restrictions, procedural or otherwise, on the use of soft law acts. The first procedural requirements were introduced by the 2010 ESA Regulations, which implemented the basic requirements of the principles of transparency and participation. For instance, article 16 requires that the authorities conduct open public consultations and analyze the act’s potential costs and benefits before issuing guidelines or recommendations, though only where the authorities themselves considered this to be appropriate. Consultations and analyses must also be proportionate to the scope, nature, and impact of the guidelines or recommendations and the opinion of the relevant stakeholder group must be requested—again where appropriate.

The question of whether the ESAs’ soft law powers should be subjected to more stringent procedural restrictions surfaced in 2017 along with the scheduled review of the ESA Regulations. Citing increasing demand from stakeholders, the Commission proposed a significant enhancement of the ESAs’ procedures to issue guidelines and recommendations.Footnote 39 According to the proposal, the ESAs should, save in exceptional circumstances, conduct open public consultations regarding the relevant guidelines and recommendations, and always assess their cost and benefits.Footnote 40 This higher standard did not survive the trilogue negotiations, so the flexible “where appropriate” standard therefore remains in place. The revised article 16 nevertheless requires the ESAs to provide reasons if they choose not to consult the public, or choose not to request a prior advice from its stakeholder group.Footnote 41

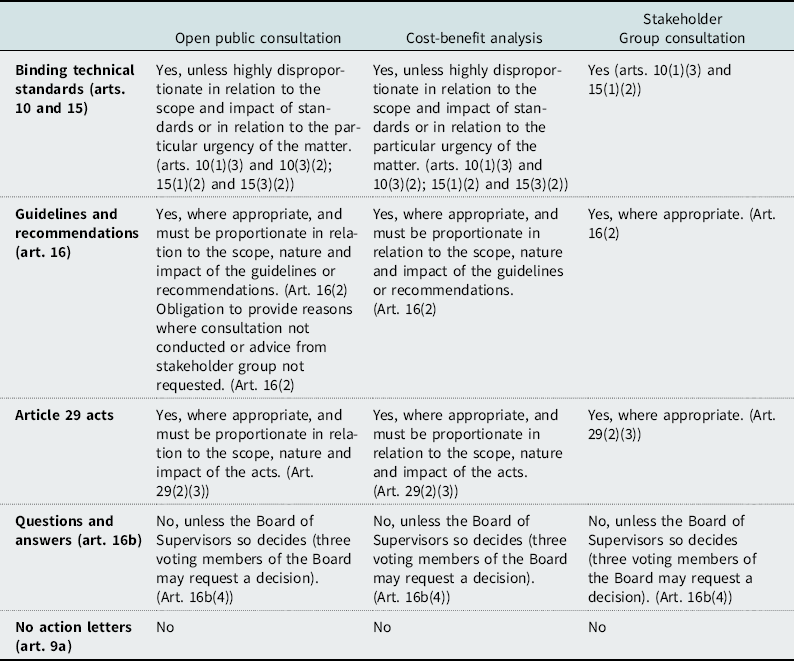

Table 1 summarizes the procedural framework for the ESAs’ soft rulemaking post 2019 reform. As the table shows, a procedural standard similar to Article 16—the “where appropriate” standard—now applies to all Article 29 acts. This levels the procedural playing field in formal terms, although it remains to be seen where the standard will de facto settle, given that this is for the ESAs to decide.

Table 1. Procedural control of ESA soft law acts

As the table shows, however, the Q&A procedure remains thoroughly informal. The ESAs need not consider whether to conduct public consultations on draft answers or whether to assess their answers’ costs and benefits. Such extreme informality of Q&As could indeed be used to shortcut procedures for more formal regulatory instruments, such as guidelines.Footnote 42 To safeguard against this risk, the 2019 reform introduced a simple internal procedure. If requested by three voting members of the ESA Board of Supervisors, the Board may decide, by simple majority, whether “the admissible question” is of such a nature that it should be addressed in guidelines, thus triggering the usual Article 16 procedures. Following the same procedure, the Board may decide whether the ESA should conduct open public consultations or to analyze related costs and benefits of its answers or whether it should request advice from the ESA’s stakeholder group following the Article 37 procedure.

The 2019 reform also addressed certain transparency problems in the Q&A procedure.Footnote 43 Article 16b (3) now requires that the ESAs develop a web-based tool to facilitate the submission and publication of questions received as well as the publications of answers to admissible questions.Footnote 44 The Article also clarifies that questions may be asked by any natural or legal person and questions may relate to the practical application or implementation of all the legislative acts falling under the ESAs’ mandate, the associated delegated and implementing acts—including Binding Technical Standards, as well as guidelines and recommendations.Footnote 45 Under Article 16b(5) the question must be forwarded to the Commission where it requires the interpretation of Union law.

Table 1 also shows that the new Article 9aFootnote 46 for no action letters implements no procedural standards safeguarding public input. The provision does not require the ESAs’ to undertake an impact analysis either. This is probably because the new article did not create new powers. In fact, rather than introducing genuine forbearance powers, for example, temporary intervention powers hierarchically superior to those of national competent authorities, Article 9a gives the ESAs a simple advisory function. The new procedure is designed to address certain exceptional situations where a direct conflict materializes between two legislative acts or where the absence of relevant rules gives rise to unforeseen compliance problems. The procedure entails the ESAs sending detailed accounts to the national competent authorities and to the Commission about the issue at hand, as well as issuing opinions—in the form of draft rules—to the Commission regarding possible legislative actions required. Only after fulfilling these advisory tasks, and pending the adoption new rules addressing the situation—which would include possible consultations and analyses—the ESAs must issue an opinion “with a view to furthering consistent, efficient and effective supervisory and enforcement practices, and the common, uniform and consistent application of Union law”. The legal status of such no action “opinions” is identical to any other non-binding measure adopted under Article 29(2). For instance, the competent authorities are not required to inform the ESAs if they intend to follow the opinion.

In other words, the new rules on no action letters seem to restrict rather than enable their use. In terms of legal certainty, the industry will probably find little comfort in the requirement under Article 9a(2) that the ESAs must, when invoking the new “no action letter” instrument, “act expeditiously, in particular with a view to contributing to the prevention of the issues […], whenever possible.”

C. What Degree of Procedural Control for ESA Soft Law?

As the preceding section showed, the ESAs’ rulemaking functions are subject to varying degrees of procedural control. The recent review of the ESA regulations moderately upgraded the formal requirements and made the procedural framework more consistent, particularly with respect to Article 29 instruments. Many would undoubtedly welcome the reform as a step towards legitimizing the ESAs’ soft law function and reducing the procedural gap between soft law and more binding forms of rulemaking.Footnote 47 This section assesses proceduralization of ESA soft law from another perspective, focusing on the issue of what effect, if any, might higher procedural standards have on the form and substance of ESA rulemaking. The main problem with proceduralization, it is argued, is that without effective ex post review even mandatory requirements would have little effect. Paradoxically, however, raising procedural standards through intensive court review would risk causing certain unintended and counterproductive consequences.

I. The Questionable Value of Mandatory Procedures

Article 8(3) of the revised ESA Regulations require the ESAs to meet sufficient standards of procedure and of better regulation when exercising their powers. Apart from the provisions applying to binding technical standards, however, the regulations leave the ESAs varying degrees of discretion to decide when to conduct public consultations or cost-benefit analyses. Why such discrepancy? After all, strengthening procedural control infuses the ESA rulemaking with fundamental constitutional values and thus gives effect to the fundamental right to good administration.Footnote 48 Surely the best way to ensure participation and transparency would be by making such procedures mandatory—or near-mandatory—as the Commission proposed in 2017?Footnote 49

As a standalone measure, mandatory procedures would probably make little difference. Despite the “where appropriate” standard, the ESA’s guidelines are invariably preceded by an open public consultation as well as a cost-benefit analysis. Indeed, the problem is not whether they are conducted so much as how. This is particularly the case with ESMA’s costbenefit analyses, most of which have been very brief and high-level. Few assessments, if any, have attempted a detailed and quantitative analysis. For an extreme example, ESMA’s Consultation Paper on remuneration guidelines include a simple note stating that the benefits of the guidelines “are potentially significant even if difficult to quantify, due to the nature of the topic.”Footnote 50 ESMA has itself admitted that quantifying its acts’ costs and benefits is difficult without better input from the market participants.Footnote 51 It has also noted the technical difficulty of disentangling the effects of its proposed guidelines from the effects of legislative acts and binding technical standards, for which the Commission often conducts its own impact assessments.Footnote 52

The more difficult question, then, is how to ensure that the ESAs’ consultations and analyses are, in substance, “proportionate to the scope, nature, and impact of the measures” in question.Footnote 53 Who should determine this standard, and what should be the consequence if the ESAs failed to meet the standard? Should the Court of Justice be able to annul a guideline if an ESA failed to quantify or otherwise adequately assess the guideline’s costs and benefits? The efficacy of such an interventionist approach, as the following sections shows, can be questioned.

II. Reviewing Procedural Rules: the United States Experience

Until the 1940s, federal administrative rulemaking in the United States needed to comply with few procedural rules. For instance, in 1942 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) wrote and adopted its famous anti-fraud Rule 10b-5—which still provides the main basis for the SEC’s investigations into security fraud claims—within one day and without any external control or input.Footnote 54 Already since 1946, however, the Administrative Procedure Act has required that federal agencies generally provide notice and opportunity for affected parties to comment on draft rules. Administrative rulemaking must also comply with various review standards, such as the requirement that rulemaking must not be “arbitrary” or “capricious.”Footnote 55 The SEC must additionally consider whether the considered action will promote efficiency, competition, and capital formation.Footnote 56 These enhanced procedural requirements and standards took long to translate into judicial practice.Footnote 57 The gradual transformation culminated in the famous 2011 decision Business Roundtable v. SEC,Footnote 58 which concerned an SEC rule permitting shareholders to nominate board members. Challenged by two lobby bodies, the rule was invalidated by a court in Washington, D.C., which held that “the SEC had acted arbitrarily by failing to weigh costs and benefits of the action.” According to the court, the SEC had failed to quantify certain costs without explaining why those costs could not be quantified.Footnote 59

The Business Roundtable decision demonstrates the main drawback of strict procedures; an unwelcome status quo bias.Footnote 60 It is difficult to quantify the benefits of regulation compared to the relative ease of measuring increased compliance costs.Footnote 61 The effects of financial regulation are also difficult, if not impossible, to anticipate because the financial systems adapts to rules in unpredictable ways.Footnote 62 Most also agree that judges are not bestsuited to review cost-benefit analyses after the fact, let alone to conduct one by themselves.Footnote 63

Strict procedural rules could also hinder the agencies’ ability to effect timely responses to social problems. In the U.S., the stifling effect of proceduralization on rulemaking—also known as the “ossification thesisFootnote 64”—is often joined with a prediction that administrative procedures are also ineffective because agencies can simply abandon costly and overproceduralized forms of rulemaking in favor of less formal instruments and novel ways of disseminating information.Footnote 65 The standard argument goes: “Would any of these proposals [enhancing rulemaking procedures] actually curb agency use of these informal means of setting policy? Or would they push agencies toward even more informal instruments?”Footnote 66 In other words, like financial firms, financial regulators may also adapt to rules in unpredictable ways. The ossification thesis has been widely embraced in the U.S. despite mixed, at best, empirical support.Footnote 67 The above-discussed Business Roundtable case nevertheless illustrates well the prevailing concern: the rule invalidated in the Business Roundtable v. SEC was a binding administrative rule, which was struck down regardless of the costly and time-consuming procedures that preceded the rule’s adoption.Footnote 68 Why should the agency issue rules in a binding form if it can achieve its objectives using a less formal instrument and a more flexible procedure? Indeed, it has been found that the proliferation of informal rulemaking in the United States since the 1960s has been closely associated with the better capability of informal rules—which are binding—to withstand judicial review. Gradual proceduralization and judicial scrutiny of informal rulemaking, in turn, have coincided with the proliferation of even more informal means of regulation, such as interpretative guidance.Footnote 69 According to the Administrative Procedures Act, U.S. federal agencies can still issue guidance such as “interpretative rules” or “policy statements” without using the notice and comment procedure and such acts will not generally be reviewable by courts either.Footnote 70

In the United Kingdom, Martyn Hopper and Julia Black have cited similar experiences when welcoming the fact that the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is not required to consult the public or perform cost-benefit analyses before issuing non-binding guidance. This apparent relaxation of procedural standards represents, according to Hopper and Black, an improvement because it might stop the practice of creative compliance where legislation is complied “by issuing guidance but calling it something else….”Footnote 71

The next section assesses these arguments against proceduralization in the European context.

III. The Risk of Ossification and Creative Compliance in Europe

In Europe, the risk of ossification of rulemaking due to burdensome procedures appears distant. First, the European case seems categorically different because of the distinct taxonomy of ESA acts. Unlike agencies in the United States and the UK, the only generally applicable acts that the ESAs can issue themselves are non-binding soft law acts.Footnote 72 If everything is informal, there is nowhere to escape. In closer assessment, as presented above, the ESA’s soft law toolbox is as diverse as the procedural requirements are versatile, both in letter and in substance. Article 16 guidelines and recommendations, in particular, stand out due to the tailored “comply or explain” regime through which the acts are incorporated into member states’ jurisdictions. Indeed, these acts are formal legal acts in all but name and they have gained an unusual regulatory status in the EU financial markets, where they act as a type of substitute for more formal powers to issue generally binding rules for the single financial market.

As discussed above, the ESAs’ quasi-formal powers were invented and partly grew up in a procedural vacuum. The ESAs still enjoy wide discretion to determine both when and how to conduct consultations and cost-benefit analyses before issuing guidelines. Regardless of such flexibility, conducting consultations and impact analyses has become established ESA practice and upgrading the requirement would probably change little. For instance, those few occasions where ESMA has considered it appropriate to forgo the assessment entirely have been met with instant criticism and calls for further proceduralization of these powers.Footnote 73 The revised ESA Regulations also introduced certain new legitimacy enhancing mechanisms. First, the ESAs must provide reasons if they choose not to consult the public, although this duty does not apply to cost-benefit analyses. Second, they must respect the principles of proportionality and of better regulation in conducting their assessments and analyses. More generally, the ESAs’ choice of action should also be guided by the principles of transparency and proportionality.Footnote 74

Such gradual hardening of procedural controls over ESA soft law, particularly guidelines and recommendations, hardens the nature of these acts as genuine regulatory instruments. In terms of “ossification,” however, the proceduralization appears not to have affected the popularity of guidelines as the main regulatory instrument of ESAs. One reason for this might be that, unlike in the U.S., the risk of court review of procedural standards remains null. The degree and intensity of Court control over agencies actions substantially influences the agencies’ choice of policymaking form.Footnote 75 The CJEU is not entirely without means to examine manifest breaches of procedural requirements, such as proportionality, but such claims have small chances of succeeding.Footnote 76 The Commission has explicitly opposed “over-legalistic” scrutiny of its own executive rulemaking, arguing that it would only inhibit “timely delivery of policy” while citizens expect European institutions to “deliver on substance rather than concentrating on procedures.”Footnote 77

If the ossification thesis is correct—and if the U.S. administrative law experience with informal rulemaking is of any guidance—the gradually increasing procedural burden over ESA guidelines and recommendations increases the risk that part of the ESAs’ soft rulemaking will shift from guidelines and recommendations to other categories of ESA soft law. But it is also the case that Q&As and Article 29 instruments have an informal quality that the Article 16 guidelines and recommendations do not possess. The “comply or explain” regime of Article 16 has not followed the expansion of the ESA’s soft law toolbox, nor should it. In order to preserve sufficient regulatory flexibility, the inherent informality of this regulatory space should be preserved, not suffocated. Over-proceduralizing “genuine” soft law instruments could only spur further regulatory innovation and complicate the regulatory apparatus.

There are also less radical ways of promoting rulemaking procedures. The ESA Regulations could require the ESAs to develop clear internal guidance on how and when to conduct consultations and impact assessments. An act’s validity could then be assessed by the Court if the ESAs were to depart from such “self-imposed and selfbinding” guidance.Footnote 78 To give further substance to the better regulation principles, the ESAs could also be required to set up a joint entity similar to the Regulatory Scrutiny Board which controls the quality of the Commission impact assessments and evaluations.Footnote 79 A seed on such a body might in fact have been sown in the recent review of the ESA Regulations, which now require the ESAs to establish a specific committee advising them as to how their “actions and measures should take account of specific differences prevailing in the sector, pertaining to the nature, scale and complexity of risks, to business models and practice as well as to the size of financial institutions and of markets.”Footnote 80

D. Judicial Control of ESA Soft Law

I. The Need for Ultra Vires Review

Most soft law acts function as guidance documents aiding the interpretation of some underlying actual law. The often-used term “post-legislative guidance” itself suggests the normative criterion; the act must be based on, or derive its value from, an existing legislative act.Footnote 81 Without such connection, soft law becomes a purely synthetic instrument or, in more contemporary terms, “crypto legislation.”Footnote 82 The ESA Regulations seek to prevent this by requiring that the ESAs’ must always act within their powers and within the scope of legislative acts enumerated in Article 1(2) of the ESA Regulations, also when adopting generally applicable soft law acts.Footnote 83 There are two principal ways in which the ESAs’ can exceed these limits when issuing soft law. First, the act might not have sufficient substantive connection to the underlying legal act. For instance, ESMA’s 2012 guidelines on highfrequency trading and algorithmic tradingFootnote 84 were arguably not “post-legislative” so much as “pre-legislative” in character. The guidelines were issued before the extensive MiFID review, which was on-going at the time, had been finalized. In its final report on the guidelines, ESMA noted in passing the legal issue of its proactive intervention, if only to conclude that while “the timing for completion of the MiFID review is uncertain […] there is a scope for action from ESMA in the meantime.”Footnote 85 The fact that most of ESMA’s HFT guidance became law under the subsequent MiFID II confirms the maxim that “soft law of today becomes the hard law of tomorrow.”Footnote 86 ESMA was probably well aware of its unusually proactive form of legal action, consulting market participants more extensively than usually. It even conducted a relatively granular cost-benefit analysis.

Another way an ESA could exceed its powers is by trying to give the soft law act binding legal effects that the act should not have. Here the ESMAs’ 2018 statement on the LEI code provides a good example. The statement was not issued to interpret an existing piece of legislation but rather to render a part of it temporarily ineffective. Lifting the full force of law without formalized procedures or risk assessments of course raises serious legitimacy issues.Footnote 87 The statement was particularly problematic considering that ESMA did not have such forbearance powers, the LEI requirements were based on a binding EU regulation that did not specify alternative compliance arrangements; and enforcing compliance with the act in question was not the responsibility of ESMA in the first place.Footnote 88

Both examples highlight the need for a more effective ex post control of soft rulemaking. This final section of the article considers the existing mechanisms for reviewing the legality of ESA soft law measures. The focus will be on alternative ways of accessing the Court of Justice especially for individual claimants.Footnote 89 Finally, the section reviews briefly the curious executive oversight mechanism introduced by the 2019 ESA reform.

II. The Review of Agency Acts Under Article 263 TFEU: a Road Less Travelled

The only soft law acts recognized by the Union primary law are recommendations and opinions which, as Article 288 TFEU provides, shall have no binding force. Nevertheless, the possibility of challenging the validity of formally non-binding acts before the CJEU is wellestablished Union law. The Court of Justice has, since 1971, held that an action for annulment must be available for “all measures adopted by the institutions, whatever their nature or form….”Footnote 90 Article 263(1) TFEU explicitly provides that this possibility extends to such acts of bodies, offices or agencies of the Union that intend to produce legal effects visà-vis third parties. When assessing the admissibility of soft law acts, the Court generally assesses the relevant act’s content and context, as well as the intention and powers of the issuing body.Footnote 91 The jurisdiction of the Court has been successfully invoked in cases in which Commission acts have added something material to the relevant primary or secondary legislation or introduced a “new obligation.” All successful cases have concerned a Commission act using “imperative wording.”Footnote 92 Article 263 has also been successfully invoked to invalidate a Commission act that was evidently meant to by-pass a political gridlock.Footnote 93

The Commission has recognized at least the theoretical option of using Article 263 TFEU also for bringing ESA soft law before the CJEU.Footnote 94 In practice, however, the court’s threshold for reviewing soft law acts remains high.Footnote 95 Moreover, the ESA soft law acts are carefully drafted to avoid imperative wording and often include explicit disclaimers about the act’s nonbinding status. There have been notable exceptions, such as the ESMA’s abovediscussed LEI Code statement, which sought to sidestep mandatory legal rules for a temporary period of six months. The statement arguably did not add to so much as detract from EU legislation in force, but no good legal argument exists to treat such situations differently, at least in terms of admissibility.Footnote 96

Another limitation of Article 263 TFEU is its notoriously strict rules on standing. A direct action by a natural or legal person would require that the act is specifically addressed to that person or that it is of direct and individual concern to them. No generally applicable ESA soft law act would probably meet this criteria. The rules are less strict for “regulatory acts,” which do not entail implementing measures; these acts must only be of direct concern.Footnote 97 While this definition captures “non-legislative acts,” such as the Commission’s delegated and implementing acts—and binding technical standards developed by the ESAs under Articles 10 and 15 of the ESA Regulations—it hardly extends to non-binding acts such as ESA opinions, statements, or Q&As.Footnote 98

ESAs soft law acts, such as guidelines or Q&As, could therefore be challenged only exceptionally via Article 263 TFEU if they were used clearly to circumvent or pre-empt normal rulemaking procedures—as in Commission v France (Pension funds)—or if they clearly added to, or subtracted from, a binding legislative text using imperative wording. Moreover, since soft law acts are issued in the form of generally applicable acts, and are only very exceptionally addressed to market participants directly, they are actionable only by privileged applicants, such as a member state, the European Parliament, or the Council or the Commission.Footnote 99

III. Challenging ESA Acts via National Courts: a New Opening

Another way to challenge Union soft law acts before the CJEU is via the preliminary ruling procedure under Article 267 TFEU. The non-binding nature of Commission acts has not prevented the Court from exercising its jurisdiction to issue authoritative interpretations of Commission recommendations, as in Grimaldi.Footnote 100 The same ruling affirmed that the Article 267 TFEU procedure could also be used to challenge the legal validity of soft law acts.Footnote 101 The court’s doors for such challenges have nevertheless remained shut, until very recently. In 2018 the court admitted a question about the legal validity of a Commission Banking communication based on an ultra vires claim without even applying the legal effects test or discussing the recommendation’s character as a non-binding instrument.Footnote 102 At this stage, however, it was still considered unlikely that the court would extend this more flexible approach to acts other than those adopted by EU institutions.Footnote 103 This changed in a judgment issued in March 25, 2021 in which the CJEU took the historic step of declaring an EBA recommendation invalid, if only in part.Footnote 104

The ECJ recently had another chance to consider its approach vis-à-vis non-binding ESA acts. The case C-911/19 Fédération Bancaire Française (FBF) v Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR) concerned the validity of an EBA guideline concerning certain governance requirements applicable to manufacturers and distributors of retail banking products. The case was set to make waves after Advocate General Bobek opined that the EBA exceeded its powers in adopting the guidelines and that the Court should therefore declare them invalid.Footnote 105 Although the court did not agree with the Advocate General on merits, it did admit the validity question and even answered the question after carefully scrutinizing it.Footnote 106 The EU legal framework therefore now recognizes an indefinite number of soft law acts which do not qualify as binding legal acts but which could still be declared invalid, at least via the preliminary reference procedure, as if they did.

The FBF judgment may open the door for a new generation of soft law litigation before EU courts. The Court confirmed that the strict standing rules of Article 263 TFEU do not apply to the preliminary ruling procedure. Member state courts are free to refer to the court legal challenges brought, for example, by trade associations such as Fédération bancaire française. While the ruling is a welcome step towards a more complete system of legal remedies, it also lays bare certain structural flaws and inconsistencies in the Union’s system of legal remedies with regard to soft law measures.Footnote 107

In practice, FBF will probably encourage further challenges of ESA guidelines and recommendations which become ingrained in national legal systems via the “comply or explain” mechanisms of Article 16 ESA Regulations. An intensifying scrutiny could have knock-on effects and one should not be surprised if the more “risky” part of ESA rulemaking,—for example, those straddling the boundaries of their mandates—would move to more informal specimens of soft law. Q&As, opinions, statements. also have the advantage that their use does not involve national incorporating acts. The latter, as the FBF judgment shows, now operate as tokens for accessing the CJEU via Article 267 TFEU.

IV. Controlling ESMA’s Direct Supervisory Powers

Enabling judicial review of ESA soft law via the preliminary ruling procedure also excludes one important but steadily growing area of ESA soft law. Unlike EBA and EIOPA, ESMA exercises considerable direct authority over market participants.Footnote 108 Since its inception, ESMA has acted as the pan-European supervisor for Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) and Trade Repositories, thus being in charge of all supervisory tasks from registration to enforcement.Footnote 109 The ESMA also exercises substantial oversight powers over certain third-country infrastructure providers. Starting January 2022, ESMA also begins as the direct Union-level supervisor of EU critical benchmarks and their administrators as well as certain data service providers.Footnote 110

None of the acts adopted by ESMA within its remit of direct supervision are challengeable before national courts. As they are not addressed to national authorities there is no national incorporating act to challenge. Where does this leave the directly supervised entities in terms of legal protection, particularly considering the structural shortcomings of Article 263 TFEU? The situation is less hopeless than would at first appear. First, the legal nature of EU soft law acts changes when they are adopted and applied as an instrument of direct administration. Ample case law provides that if the Commission issues non-binding guidance concerning its own future decision-making, general principles such as legitimate expectations, legal certainty and equal treatment limit the Commission’s ability to depart from the guidance.Footnote 111 The same general principles should protect the addressees of acts of EU agencies, where such powers are conferred on them. CRAs, trade repositories and other directly supervised entities should therefore be equally entitled to rely on ESMA’s soft law guidance as if it were unilaterally binding on ESMA. The ESMA itself notes on its website that “in the areas where ESMA is the direct supervisor of financial market participants, Q&As act to inform its approach.”Footnote 112

Case law such as case C-189/02, P Dansk Rørindustri and Others v Commission suggest that in such areas of direct administration, generally applicable soft law acts may qualify as the subject-matter of an objection of illegality.Footnote 113 Danske Rorindustri also provides an example of the most straightforward way to challenge the legality of such acts: by way of an ancillary plea to a challenge of ESMA’s individual decision, which either applied or departed from the challenged act. Such decision, like all binding decisions of ESAs’, can be appealed to the ESAs’ joint Board of Appeal. The Board’s decisions, in turn, are challengeable before the CJEU.Footnote 114 Nonetheless, a direct action under Article 263 TFEU would hardly succeed.Footnote 115 In terms of effective legal protection, it would be tempting to entertain an argument that such direct administrative acts, given their distinct binding character, could qualify as “regulatory acts” in line with Article 263(4)) TFEU. This would open a direct access to CJEU for “directly” concerned individuals and legal persons.Footnote 116

V. Executive Oversight of ESA Soft Rulemaking

As the preceding sections have shown, invoking the CJEU’s jurisdiction to review the legality of ESA’s soft law acts remains a difficult task despite recent developments. To address this apparent gap in legal protection, the 2019 ESA reform introduced an innovative remedy. Article 60a of the ESA Regulations provides that any natural or legal person may send reasoned advice to the Commission if that person is of the opinion that the Authority has exceeded its competence when issuing guidelines or questions and answers, but provides no further detail on the procedure. In fact, it does not even require the Commission to provide a reasoned response to the reasoned advice. What the Article does, however, is replicate the strictest standing requirements of Article 263 TFEU by providing that a person may send the reasoned advice to the Commission only if the act in question is of direct and individual concern to that person. It is hard to imagine a situation in which a generally applicable guideline, let alone a Q&A document, would meet that standard. Such executive oversight mechanisms are a poor substitute for effective judicial review and are unlikely to exert any disciplining effect on the ESAs’ use of their soft rulemaking powers.Footnote 117

E. Concluding Remarks

Ever since the establishment of the Lamfalussy Committees in the early 2000s, the process of regulatory innovation in the EU financial markets has been facilitated rather than disciplined. The most successful and important soft law acts—guidelines and recommendations, Q&As, no action letters—have also been recognized by subsequent legislative reforms. This approach has allowed the ESAs to alleviate legal problems quickly and flexibly where necessary while supporting the evolution of the European system of financial supervision. At the same time, such dynamics have significantly expanded the Union’s “shadow rulemaking” system which operates at the margins of public law.

The procedural control of ESAs’ soft rulemaking has increased gradually. The 2019 ESA reform updated several procedural requirements for the issuance of ESA soft law. The new standards, somewhat stricter as they are, are unlikely to influence greatly the form and substance ESAs’ rulemaking, e.g. by prompting escape to more informal acts. This is especially because, while the amount and diversity of ESA soft law instruments have multiplied, the judicial review of these acts has remained nonexistent. The risk of judicial review has therefore exerted little disciplining effect on the ESAs’ use of their soft rulemaking powers. In terms of rulemaking procedures, this need not be a bad thing. Over-proceduralizing “genuine” soft law instruments would cripple the ESAs’ ability to provide market participants and national authorities with relevant information and interpretative guidance. It could also complicate the regulatory system by spurring new regulatory innovations motivated by wrong reasons. In terms of ultra vires review, however, credible judicial checks are needed. Recent judicial developments such as the FBF judgment suggest that the Court of Justice might be reconsidering its approach to soft law, in general, and ESA guidelines and recommendations, in particular. The latter acts, which are regulatory acts in all but name, deserve closer scrutiny.