1. Structural guidance in anaphora resolution

Pronouns present the interpreter of natural language with a difficult task: the meaning of a pronoun is not fixed, but determined by grammatical constraints and pragmatic context. The grammatical constraints include the Binding Principles (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1981). Binding Principle A requires that reflexives have a local antecedent within the clause. The reflexive herself in (1a) must corefer with the girl, the subject of the clause, and not with a noun phrase in the embedded relative clause (e.g., the teacher). Binding Principle B requires the opposite for pronouns: the pronoun her in (1b) may corefer with a noun phrase in the embedded clause, but not to the subject of its own clause.Footnote 1

(1)

a. The girl

$_1$

$_1$  $[ $who impressed the teacher

$[ $who impressed the teacher $_2] $ saw herself

$_2] $ saw herself $_{1/\ast 2}$ in the newspaper.

$_{1/\ast 2}$ in the newspaper.b. The girl

$_1$

$_1$  $[ $who impressed the teacher

$[ $who impressed the teacher $_2] $ saw her

$_2] $ saw her $_{\ast 1/2}$ in the newspaper.

$_{\ast 1/2}$ in the newspaper.

While the Binding Principles hold of the interpretations ultimately assigned to anaphoric elements, questions arise about when, in incremental processing, the Binding Principles come into play. A growing body of psycholinguistic research, including behavioural measures and neurological responses, indicates that the structural constraints encoded by Binding Theory (BT) are heavily weighted in determining which antecedents are retrieved in initial processing (Nicol and Swinney Reference Nicol and Swinney1989; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Wexler and Holcomb2000; Sturt Reference Sturt2003; Kazanina et al. Reference Kazanina, Lau, Lieberman, Yoshida and Phillips2007; Xiang et al. Reference Xiang, Dillon and Phillips2009; Chow et al. Reference Chow, Lewis and Phillips2014). Many of these studies employ a Gender Mismatch design. It has been established that anaphors that mismatch the gender of an available antecedent show processing difficulty – a Gender Mismatch Effect (GMME) (Garnham Reference Garnham2001; van Gompel and Liversedge Reference van Gompel and Liversedge2003). This is true for gendered nouns like woman/man as well as nouns that encode stereotypical gender such as mechanic (Kennison Reference Kennison2003; Doherty and Conklin Reference Doherty and Conklin2017).Footnote 2 Sturt (Reference Sturt2003) tested reflexive anaphors in sentences like those in (2). In (2a), the BT-compliant antecedent (the accessible antecedent) for the reflexive is the man and it matches the reflexive in gender. The inaccessible antecedent (Alice) does not match gender expectations. This sentence poses no difficulty for the processor at the anaphor. In (2b), in contrast, the only accessible antecedent for herself is the man and it mismatches in gender expectancy, resulting in processing difficulty.

(2)

a. The man [who treated Alice] had impressed himself. no GMME

b. The man [who treated Alice] had impressed herself. GMME!

These kinds of results suggest that the processor, at least initially, does not entertain Alice as an antecedent in (2a) because it is not in a position compliant with Binding Principle A. There are also results that suggest the processor does consider inaccessible antecedents early in processing. For instance, Badecker and Straub (Reference Badecker and Straub2002) report that comprehenders access feature matching but inaccessible antecedents for pronouns, as in the girl in 1b.Footnote 3 For reflexives, Sturt (Reference Sturt2003) found late effects in eye-movements, suggesting that comprehenders consider inaccessible antecedents for reflexives in later stages of processing. More recent research suggests that structurally unlicensed antecedents can be retrieved, but that structural cues may at times nonetheless be weighted higher than other factors guiding retrieval, such as morphological cues (see Parker and Phillips Reference Parker and Phillips2017; Jäger et al. Reference Jäger, Mertzen, Van Dyke and Vasishth2020).

One case that highlights particular nuance in the role of structural constraints in guiding antecedent retrieval is investigated by Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) and Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019). They examined fronted wh-arguments and wh-predicates to probe the processor's sensitivity to structural constraints in reconstruction environments – instances where an anaphor is part of a leftward-moved constituent but nonetheless conforms to the Binding Principles as though it were evaluated in the gap position (indicated by — in the examples below). This is demonstrated by the fact that the pattern of judgments for pronouns and reflexives in their post-movement position mirrors that in their pre-movement position. For instance, the reflexive in the wh-fronted prepositional object in (3a) is licensed because it obeys Principle A in its pre-movement position, as shown in (3b), while the pronoun is unacceptable in both positions when it is co-indexed with the subject. In contrast, when the anaphor is part of wh-fronted subject, as in (4a), the reflexive is less acceptable than the pronoun, mirroring the judgments for the pre-movement sentence (4b).

(3)

a. Which painting of himself

$_1$/*him

$_1$/*him $_1$ did the duke

$_1$ did the duke $_1$ fall on _?

$_1$ fall on _?b. The duke

$_1$ fell on this painting of himself

$_1$ fell on this painting of himself $_1$/*him

$_1$/*him $_1$.

$_1$.

(4)

a. Which painting of *?himself

$_1$/him

$_1$/him $_1$ _ fell on the duke

$_1$ _ fell on the duke $_1$.

$_1$.b. This painting of *?himself

$_1$/him

$_1$/him $_1$ fell on the duke

$_1$ fell on the duke $_1$.

$_1$.

An asymmetry arises, however, between reflexives in wh-argument phrases, like those above, and those in wh-predicate phrases. This is revealed when the wh-phrase is fronted in an embedded question. Reflexives within wh-argument phrases, as in (5a) can have either the embedded subject Mary or the matrix subject Alice as an antecedent. In contrast, when the reflexive is contained in a wh-predicate phrase, as in (5b) it can only be bound by the embedded subject.

(5)

a. Alice

$_1$ recalled which drawing of herself

$_1$ recalled which drawing of herself $_{1/2}$ Mary

$_{1/2}$ Mary $_2$ had damaged _ during the summer vacation.

$_2$ had damaged _ during the summer vacation.b. Alice

$_1$ recalled how pleased with herself

$_1$ recalled how pleased with herself $_{\ast 1/2}$ Mary

$_{\ast 1/2}$ Mary $_2$ had been _ during the summer vacation.

$_2$ had been _ during the summer vacation.

Predicates are said to “totally” reconstruct (Huang Reference Huang, C-T1993; Heycock Reference Heycock1995), in the sense that they must be interpreted in their gap positions, unlike wh-arguments which allow the Binding Principles to evaluate anaphora they contain in either the surface or the gap position. (See Frazier et al. Reference Frazier, Bernadette and Charles1996 and Chapman Reference Chapman2018 for processing evidence in the case of wh-arguments.)

Even though reflexives in wh-predicates can be grammatically licensed (i.e., bound) only by embedded antecedents, Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) found evidence that the processor retrieves a matrix antecedent in wh-predicate constructions like (5b) just as it does the wh-argument constructions. Using a Gender Mismatch design, as shown in (6), Omaki compared wh-arguments and wh-predicates containing reflexives. The gender of the matrix subject was manipulated such that it either matched (Alice) or mismatched (Andrew) the reflexive. The embedded subject (e.g., nanny) always matched the reflexive in gender.

(6) Stimuli from Omaki (Reference Omaki2010)

-

wh-Argument, Gender match/mismatch

Alice/Andrew recalled which drawing of herself the attractive young nanny had damaged during the summer vacation.

-

wh-Predicate, Gender match/mismatch

Alice/Andrew recalled how pleased with herself the attractive young nanny had been during the summer vacation.

-

In an eye-tracking-while-reading study, Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) found gender mismatch effects in both the argument and predicate conditions in first pass and regression path reading times on the reflexive region. This result suggests that at least initially, the parser attempts to associate the reflexive with the matrix subject, and that this result does not differ for reflexives in predicates or arguments. In later measures, the mismatched argument conditions continued to show processing difficulty while the predicate conditions did not. In a self-paced reading experiment, Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) found that at least initially the processor considers the matrix subject to be a potential antecedent for the reflexive in both wh-predicates and wh-arguments, although the effect persisted longer for arguments.

Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) replicated the findings of Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) and revealed a further important property: the backward search that the reflexives in wh-predicates engage in is not structurally guided but rather determined by recency. They presented stimuli like those in (7), where a mismatched antecedent was either a c-commanding matrix subject or a non-c-commanding subject within a relative clause that is linearly more recent than the matrix subject.

(7) Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) Experiment 1 sample stimuli

-

Matrix Match, Embedded Match/Mismatch

The mechanic

$[ $that James/Briana hired this year

$[ $that James/Briana hired this year $] $ predicted how annoyed with himself the extremely dumb agent would be

$] $ predicted how annoyed with himself the extremely dumb agent would be $\ldots$

$\ldots$ -

Matrix Mismatch, Embedded Match/Mismatch

The mechanic

$[ $that Briana/James hired this year

$[ $that Briana/James hired this year $] $ predicted how annoyed with herself the extremely dumb agent would be

$] $ predicted how annoyed with herself the extremely dumb agent would be $\ldots$

$\ldots$

-

In an eye-tracking-while-reading study, they found that there were processing difficulties when the embedded antecedent mismatched, suggesting that the backward search is not structurally guided but perhaps determined by recency.Footnote 4 Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) suggest that there is a pressure to interpret reflexives immediately. As Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) put it, “comprehenders prefer to immediately resolve a cataphoric reflexive's reference by retrieving an antecedent in the previous context, even though this introduces the risk of a potentially incorrect interpretation.” The word “potentially” is important here, since in principle at the point of encountering the reflexive, there are continuations where a co-referential construal between the reflexive and a preceding noun phrase are possible, that is, if a co-referent embedded subject pronoun is provided downstream (Alice ![]() $_1$ recalled how pleased with herself

$_1$ recalled how pleased with herself ![]() $_1$ she

$_1$ she ![]() $_1$ had been during the summer vacation). The mismatch effect could be seen instead as a reflection of comprehenders' expectations about the content of the sentence further downstream: readers may be expecting an embedded subject co-referent with the relative clause subject, and therefore also with the reflexive, and so a gender mismatched reflexive would be unexpected. For convenience, we label this the “pronoun expectancy explanation.”

$_1$ had been during the summer vacation). The mismatch effect could be seen instead as a reflection of comprehenders' expectations about the content of the sentence further downstream: readers may be expecting an embedded subject co-referent with the relative clause subject, and therefore also with the reflexive, and so a gender mismatched reflexive would be unexpected. For convenience, we label this the “pronoun expectancy explanation.”

To address this possibility, Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) conducted a sentence completion study using materials similar to their previous experiments. The critical sentence was one that terminated before the reflexive: The mechanic that Brianna hired this year wondered how annoyed with ![]() $\ldots$. Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and DillonOmaki et al. reasoned that for the pronoun expectancy explanation to be on the right track, it would have to be shown that even before encountering the reflexive, readers have developed an expectation that the embedded subject is co-referential with the relative clause subject. They found no such preference, however, and concluded that the observed reading time measures reflect retrieval of a linearly closer antecedent which is not in any way tied to an expectation of a grammatical binder downstream.Footnote 5 The important take-away is (i) that reflexives in fronted wh-predicates retrieve antecedents from DPs that are crucially not themselves possible structural licensors for reflexives (on any continuation); and (ii) that when multiple such DPs are present, antecedents are retrieved without consideration of structural constraints (e.g., c-command). We use the term non-structurally guided search to characterize this pattern; that is, a search resulting in the retrieval of an antecedent for a reflexive that is not itself a possible structural licensor of the reflexive (although it could in principle be co-referent to the reflexive pending downstream material). If what Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) found is indeed an instance of non-structurally guided search, this result is surprising given the body of literature suggesting that reflexives, at least to some degree, initiate structurally guided searches.

$\ldots$. Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and DillonOmaki et al. reasoned that for the pronoun expectancy explanation to be on the right track, it would have to be shown that even before encountering the reflexive, readers have developed an expectation that the embedded subject is co-referential with the relative clause subject. They found no such preference, however, and concluded that the observed reading time measures reflect retrieval of a linearly closer antecedent which is not in any way tied to an expectation of a grammatical binder downstream.Footnote 5 The important take-away is (i) that reflexives in fronted wh-predicates retrieve antecedents from DPs that are crucially not themselves possible structural licensors for reflexives (on any continuation); and (ii) that when multiple such DPs are present, antecedents are retrieved without consideration of structural constraints (e.g., c-command). We use the term non-structurally guided search to characterize this pattern; that is, a search resulting in the retrieval of an antecedent for a reflexive that is not itself a possible structural licensor of the reflexive (although it could in principle be co-referent to the reflexive pending downstream material). If what Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) found is indeed an instance of non-structurally guided search, this result is surprising given the body of literature suggesting that reflexives, at least to some degree, initiate structurally guided searches.

The results reported in Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) and Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) raise a number of questions about antecedents retrieved in a non-structurally guided way. To what extent do readers ever commit to this antecedent? If the non-structurally guided retrievals are pursued by readers at the “risk” of potentially introducing an incorrect interpretation, as Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) put it, are readers more willing to abandon it? In fact, there is suggestive evidence in Omaki (Reference Omaki2010)'s reading time studies that the mismatch effect is more short-lived with reflexives in predicates than arguments. Similarly, Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019)'s Experiment 2 found attenuated mismatch effects in eye-tracking measures for reflexives in fronted wh-predicates compared to non-fronted wh-predicates. They offer a speculation – albeit emphasizing its post hoc nature – that the readers may have quickly realized that the retrieved antecedent would not be grammatically licensed and therefore moved on to a forward search, thus minimizing the gender mismatch effect.

Our studies investigated the non-structural retrieval by reflexives in wh-predicates by asking three questions: (i) Do comprehenders maintain any commitment to the non-structurally guided interpretation of the reflexive? (ii) Does the processor continue to search for an antecedent? and (iii) Do reflexives in wh-predicates differ from those in wh-arguments in this second, forward search?

The first question is motivated by findings from garden path processing showing that comprehenders will often maintain commitments of an initial analysis even after reanalysis (Christianson et al. Reference Christianson, Hollingworth, Halliwell and Ferreira2001; Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Christianson and Hollingworth2001; Sturt Reference Sturt2007; Slattery et al. Reference Slattery, Sturt, Christianson, Yoshida and Ferreira2013). These so-called “lingering” effects were observed by Christianson et al. (Reference Christianson, Hollingworth, Halliwell and Ferreira2001) for garden path sentences such as (8):

(8) While Anna dressed the baby played in the crib.

Participants would incorrectly answer the question Did Anna dress the baby? at rates as high as 70%. These incorrect interpretations can be quite long-lasting, too, lingering past the clause boundary (Slattery et al. Reference Slattery, Sturt, Christianson, Yoshida and Ferreira2013). We asked whether, in cases where reflexives in fronted wh-predicates retrieve matrix antecedents, such interpretations ever linger. Following Omaki's (Reference Omaki2010) and Omaki et al.'s (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) online evidence, we might expect that on at least some trials, participants will commit to ultimately ungrammatical antecedents for reflexives in fronted wh-predicates. However, if antecedents retrieved by a non-structurally guided search are only tenuously maintained, we may not expect to see very strong effects of this “maintenance” in comprehension.

As for the second and third questions, we expect evidence for reanalysis in the wh-predicate cases, and the question is whether this will occur immediately upon encountering a grammatically accessible antecedent. The core question here is whether the search for an antecedent continues after a failed retrieval, and whether reflexves in wh-predicates and wh-arguments differ in this respect. The question of whether antecedent search continues after failed retrieval has been recently investigated by Giskes and Kush (Reference Giskes and Kush2021). They asked whether, like wh-filler gap processing, antecedent retrieval is persistent: that is, does the processor continue to actively search for an antecedent after a first prediction is disconfirmed. They examined cataphoric pronouns in sentence-initial adjunct clauses in English and Norwegian. They found that, as in earlier studies, readers slowed down when the matrix subject mismatched the pronoun in gender (van Gompel and Liversedge Reference van Gompel and Liversedge2003; Kazanina et al. Reference Kazanina, Lau, Lieberman, Yoshida and Phillips2007). Crucially, they also observed a gender mismatch effect on objects (like Jonathan in (9)), when the first-encountered subject (a group of customers) mismatched the cataphor (he/she) in notional number. They argue that readers continued an active search for an antecedent after the first candidate antecedent proved to be non-viable, just as active wh-fillers persist in seeking a gap after earlier gap sites are discovered to be filled (e.g., Stowe Reference Stowe1986 and following).

(9)

-

While he/she was taking the orders, a couple of customers annoyed Jonathan accidentally by laughing at the waitress’ voice.

-

In the current studies, we exploit the possibility of persistent search to determine when readers abandon a matrix antecedent construal for reflexives in wh-predicates. If, given the suggestive evidence in Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019), readers realize that a matrix antecedent is not a grammatical licensor for the reflexive, then we expect a continued search. In Experiment 2, a self-paced reading study, we present readers with gender-matched matrix antecedents for reflexives in wh-predicates, but which were then followed by a mismatching embedded subject. If readers abandon the matrix antecedent (i.e., treat it as a failed retrieval), then the search should persist and a mismatching embedded subject should cause a disruption. The predictions are the same, but for different reasons, on the pronoun expectancy explanation of Omaki et al.'s (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) findings, discussed above. If participants expect a co-referent embedded subject, we should see processing disruption if that subject does not match the expected gender of the matrix subject and reflexive. Our studies do not distinguish between these two options. We acknowledge that if the pronoun expectancy explanation is correct (but again see Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and DillonOmaki et al.'s Experiment 3), it would not be particularly surprising to find a gender mismatch effect at the embedded subject. In contrast, if the pronoun expectancy explanation is not viable, then finding a gender mismatch effect at the embedded subject would be particularly meaningful, indicating that readers abandoned the matrix antecedent before reaching the embedded subject.

We included sentences with reflexives in wh-argument phrases, with the intention that these would serve as a type of baseline. In these cases, a resolution to the matrix antecedent is entirely grammatical and structurally guided. Compared to reflexives in wh-predicates, reflexives in wh-arguments should should exhibit, on average, fewer instances of a persistent search. We might expect readers to retrieve and stick with a matrix antecedent. This expectation is motivated by the fact that there is no evidence for the processor to overturn a matrix antecedent construal. (Below we discuss the possibility that, given the ambiguity in the wh-argument sentences, the processor may continue to search and evaluate the options in later stages of processing.)

In Experiments 1a and 1b, we first explore how participants interpret the reflexive when they are explicitly asked to determine its antecedent. Our results suggest that participants largely adopt analyses in which reflexives are structurally licensed; however, depending on the task, there is some evidence that participants commit to interpretations for reflexives in wh-predicates that are not grammatically sanctioned. In Experiment 2, we investigate whether reflexives show evidence of a continued search as early as the embedded subject position. We find that they do, but there is no observable difference between reflexives in wh-predicates and wh-arguments.

2. Experiments 1a and 1b

Omaki's (Reference Omaki2010) results suggest that when arriving at a reflexive embedded within either a fronted wh-predicate or a wh-argument, the processor considers the matrix subject to be a potential antecedent even though this subject cannot be a grammatical licensor of the reflexive in the argument conditions. However, in these experiments, it remains unclear what interpretation participants eventually reached for these reflexives. They were never explicitly asked which referent (matrix or embedded subject) the reflexive referred to. In Experiment 1a, we asked how the reflexive is interpreted when participants are explicitly asked to choose between the two referents (matrix and embedded subject). Experiment 1b is a version of Experiment 1a that employs a design more closely resembling those used in the studies that find lingering effects in garden path sentences (Christianson et al. Reference Christianson, Hollingworth, Halliwell and Ferreira2001). In Experiment 1b, we show that choosing a matrix subject antecedent in wh-predicate constructions is more likely than choosing an ungrammatical antecedent in non-movement contexts. While the rates of choosing such non-structural antecedents is not overwhelmingly high, the results of Experiment 1b do suggest that non-structurally guided retrieval can affect final comprehension.

2.1 Experiment 1a

2.1.1 Materials

The same experimental items used in Omaki (Reference Omaki2010), repeated in 10, were used in Experiment 1a, a forced-choice comprehension experiment. There were a total of 24 experimental items, crossing Predicate Type (wh-argument vs. wh-predicate) and Gender (matrix subject match vs. mismatch).

(10) Experiment 1a stimuli

-

wh-Argument, Gender match/mismatch

Alice/Andrew recalled which drawing of herself the attractive young nanny had damaged during the summer vacation.

-

wh-Predicate, Gender match/mismatch

Alice/Andrew recalled how pleased with herself the attractive young nanny had been during the summer vacation.

-

For the argument conditions, participants were asked questions such as Who was the drawing of? and were given the options Alice/Andrew or the nanny.Footnote 6 For the predicate conditions, participants were asked Who was pleased? with the same options. Options were presented on the screen as radio buttons and the ordering of options was counterbalanced across trials. Participants were also presented with 32 fillers. These fillers were created to resemble experimental itemsFootnote 7 and asked similar forced-choice questions. We again alternated the order of the presentation of the options.

2.1.2 Participants and procedures

Forty-eight self-reported native and monolingual speakers of English living in the United States were recruited online using Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/) and directed to the experiment on Penn Controller for Ibex Experiments (Zehr and Schwarz Reference Zehr and Schwarz2018). Each participant received £1.75 as compensation for participation upon completion of the experiment. Participants were asked to read each sentence presented on the screen. After reading the sentence, they pressed “Continue” to see the comprehension question. The target sentence remained on the screen when the comprehension question was shown. Once they selected their answer to the comprehension question, they moved onto the next target sentence on a separate screen. They were asked to answer the questions as accurately as possible but were not provided with any feedback. The experiment began with two practice items, which were not analyzed, to familiarize participants with the task.

Four lists of stimuli were created using a Latin-square design. For each sentence template, participants saw only one condition, but they saw an equal number of each condition over the course of the experiment.Footnote 8 Order of presentation was pseudo-randomized such that participants saw no more than one experimental item in a row.

We predicted differences between the wh-argument and wh-predicate conditions. Since the referent for the reflexive is ambiguous when it is embedded in a wh-argument, we predicted that participants could choose either referent since either the matrix subject or the embedded subject is an appropriate an antecedent. The question is whether there is any evidence that in the wh-predicate conditions, readers will retrieve and maintain a commitment to the matrix subject as the referent of the reflexive, even though this is not grammatical given the global content of the sentence. We cannot provide a precise threshold for how many incorrect responses should count as evidence for a lingering interpretation, but we do note that Christianson et al. (Reference Christianson, Hollingworth, Halliwell and Ferreira2001) found incorrect or “lingering” responses at rates of 10% and above.

2.1.3 Experiment 1a results

Responses that selected the embedded subject antecedent (i.e., the result of reconstruction) were coded as 1, whereas responses that selected the matrix subject were coded as 0. Thus, higher mean proportions indicate that participants were more likely to choose the antecedent only available by reconstruction.

Since this coding resulted in a binomial distribution, we ran a logistic mixed effects regression model on the comprehension data. The model included fixed effects for Gender (match or mismatch) and Phrase Type (argument or predicate), which were sum-coded. In addition, since participants and items vary, all models included random intercepts for participants and items (Pinheiro and Bates Reference Pinheiro and Bates2000; Baayen Reference Baayen2008; Baayen et al. Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008), as implemented in the lme4 package (version 1.1-26, Bates and Sarkar Reference Bates and Sarkar2007; Bates et al. Reference Douglas, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (version 4.0.4, R Core Development Team, 2021). We used the BOBYQA algorithm for model optimization on all models. We also included random slopes for fixed effects by participants and items whenever the models converged. We initially fitted a maximal random effects structure and removed random slopes if the models did not converge. Models were compared using the ANOVA function in R to determine the best model fit. If two models did not differ significantly, we used the simpler model. We report in our tables or in the text which random effects were used in each model.

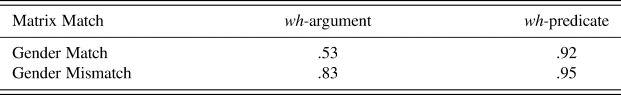

The mean proportion of responses selecting the embedded subject is shown in Table 1. Recall that a higher value means that participants were more likely to choose the embedded subject and not the matrix subject. In argument conditions, when the matrix subject mismatched the reflexive, participants chose the embedded subject 83% of the time. This result likely simply reflects an effect of gender matching. However, when both the matrix subject and the embedded subject matched the reflexive in gender, participants chose the embedded subject (available via reconstruction) about half the time (53%). This result suggests that for the argument conditions, either subject is an appropriate antecedent for the reflexive, as reported in the formal syntactic literature. In the predicate conditions, when the matrix subject mismatched the reflexive in gender, participants chose the embedded subject 95% of the time. Again, this could simply be an effect of gender matching. However, when both the matrix subject and the embedded subject matched the reflexive in gender, participants chose the embedded subject as the antecedent for the reflexive 92% of the time.

Table 1. Proportion of responses selecting the embedded subject as the antecedent for the reflexive in the forced choice experiment. Higher values reflect a preference for choosing the embedded subject over the matrix subject

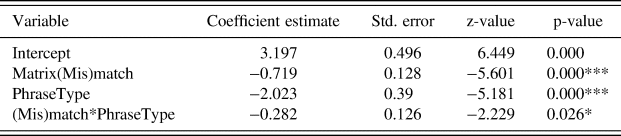

We ran a logistic regression model with an interaction between Match (whether the matrix subject matched or mismatched the reflexive in gender) and Phrase Type (argument or predicate). Random intercepts by participants and items were included as well as a by-participant random slope for Phrase Type. The model is shown in Table 2. There was a significant interaction between Matrix match/mismatch and Phrase Type.

Table 2. Final mixed-effects model for forced choice results in Experiment 1a (N = 1152), reported as the regression coefficient estimates, standard errors, z-values and p-values. Sum coding. Matrix Match/Mismatch: Match (1), Mismatch (−1). Phrase Type: Argument (1), Predicate (−1)

Random effects: by-participant intercept (SD = 2.0), by-item intercept (SD = 0.661), by-participant random slope for Phrase Type (SD = 0.86) and the correlation between by-participant random slope and random intercept (r = −0.88).

To further investigate this interaction, we ran post hoc analyses using the emmeans package in R (Lenth Reference Lenth2021). This package provides contrast estimates based on the final mixed effects model (shown in Table 2). There was a highly significant difference between Matrix Match and Mismatch for argument conditions (![]() $\beta$ = −2.0002, SE = 0.251, z = −7.963, p < 0.001*, Bonferroni corrected). The effect of Matrix Mismatch also reaches (marginal) significance in the predicate conditions (

$\beta$ = −2.0002, SE = 0.251, z = −7.963, p < 0.001*, Bonferroni corrected). The effect of Matrix Mismatch also reaches (marginal) significance in the predicate conditions (![]() $\beta$ = −0.875, SE = 0.443, z = −1.974, p = 0.048, Bonferroni corrected: p = 0.097). These results suggests that participants are sensitive to the difference between arguments and predicates and that they are more likely to choose the embedded subject as the antecedent for the reflexive in predicate conditions, even if the matrix subject matches the reflexive in gender.

$\beta$ = −0.875, SE = 0.443, z = −1.974, p = 0.048, Bonferroni corrected: p = 0.097). These results suggests that participants are sensitive to the difference between arguments and predicates and that they are more likely to choose the embedded subject as the antecedent for the reflexive in predicate conditions, even if the matrix subject matches the reflexive in gender.

2.1.4 Experiment 1a discussion

The results from the forced-choice experiment support the received wisdom from theoretical linguistics. Wh-arguments can but need not reconstruct, predicting that either the matrix subject or the embedded subject can be associated with a reflexive embedded in a wh-argument. If both subjects match the reflexive in gender, either is a suitable antecedent. However, wh-predicates must reconstruct, predicting that only the embedded subject is an appropriate antecedent. This was borne out in our results, where participants chose the embedded subject 92% of the time, even when the matrix subject matched the reflexive in gender.

While we found high rates of choosing the grammatical antecedent in the wh-predicate conditions, there is some evidence of a lingering effect, since the ultimately ungrammatical matrix antecedent was retrieved and showed a marginal difference in the post hoc comparison within the wh-predicate conditions. There are several reasons to question whether the methodology of Experiment 1a was appropriate for fully detecting a lingering interpretation. First, the fact that a grammatically licit answer option was provided, in explicit comparison to the grammatically illicit option, could have made the grammatical option more salient or prompted participants to reflect more in making a choice. Second, the target sentence remained visible while participants answered the question, providing an opportunity for deeper processing or reanalysis. In Experiment 1b, we attempt to control for these confounds with a design that more clearly resembles that of Christianson et al. (Reference Christianson, Hollingworth, Halliwell and Ferreira2001). We expect that this will bring out more ungrammatical responses, which would make a stronger case that non-structurally guided retrieval has effects on comprehension.

2.2 Experiment 1b

2.2.1 Materials

In Experiment 1b, reflexives in fronted wh-predicates, as in Experiment 1a, were tested alongside non-wh predicates that remained in situ (11). The comprehension question targeted either the matrix subject as an antecedent or the embedded subject. In one condition, the comprehension question probed whether the embedded subject would be chosen as an antecedent for the reflexive, as in (i); in the other question condition, the comprehension question probed whether the matrix subject (which is grammatically not licensed) would be chosen as an antecedent, as in (ii).

This method more closely resembles the questions posed in Christianson et al. (Reference Christianson, Hollingworth, Halliwell and Ferreira2001), where participants were asked a yes-no question consistent with a lingering interpretation (e.g., Did Anna dress the baby in (8)). A ‘Yes’ response to the questions in (11ii) for the wh-fronted predicates indicates resolution to the ungrammatical matrix antecedent. The in situ predicate conditions provide a baseline for resolution to truly ungrammatical antecedents. Here we expect only responses consistent with the grammar, whereby the embedded subject (the careless kid) binds the reflexive – a very low proportion of ‘Yes’ answers to the ungrammatical antecedent question.

Twenty-four items were constructed following the design in (11), which crossed two two-level factors: Predicate Position (wh-fronted vs. in situ) and Question Type (Embedded antecedent Q vs. Matrix antecedent Q). Four lists were created using a Latin Square design, and included 40 filler sentences. Order of presentation was pseudo-randomized such that participants saw no more than one experimental item in a particular condition in a row.

2.2.2 Participants and procedures

Forty-eight self-reported native and monolingual speakers of English living in the United States were recruited online using Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/) and directed to the experiment on Penn Controller for Ibex Experiments (Zehr and Schwarz Reference Zehr and Schwarz2018). Each participant received £2.30 as compensation for participation upon completion of the experiment.

Each trial began with the presentation of the target sentence. Participants were instructed to read this sentence at a normal speed and click a “Continue” button afterward. The target sentences then disappeared and the question appeared in its place. Participants responded to the question by clicking either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ (the position of these responses remained constant across trials). Participants pressed “Continue” to proceed to the next trial.

2.2.3 Results of experiment 1b

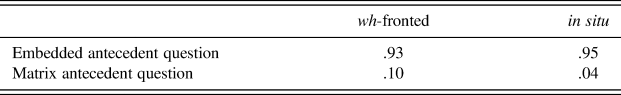

The proportion of ‘Yes’ responses for each condition is reported in Table 3 for 47 participants. One participant was excluded on the grounds that they answered the comprehension questions of the fillers (all unambiguous and not exclusively related to reflexive interpretation) at 55% correct (compared to a mean proportion of correct responses of .90 (SD 0.08)).

Table 3. Proportion of ‘Yes’ responses.

The in situ conditions showed the expected rates of ‘Yes’ responses, with high rates of ‘Yes’ for the question probing the embedded antecedent and very low rates of ‘Yes’ for questions probing the matrix antecedent. A similar pattern is found with the wh-fronted predicate conditions, although the rate of ‘Yes’ answers in support of the matrix antecedent is higher.

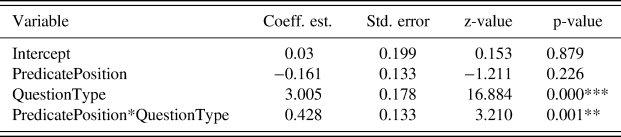

Since the data formed a binomial distribution, we fit a logistic mixed effects model to the data, with Predicate Position and Question Type as fixed effects, which were sum coded. The model, reported in Table 4, included random intercepts for participants and items. Models with random slopes by participants and items either did not converge or did not improve the model fit. In the model, there is a significant interaction between Predicate Position and Question Type.

Table 4. Final mixed-effects model for forced choice results in Experiment 1b (N = 1128), reported as the regression coefficient estimates, standard errors, z-values and p-values. Sum coding. Predicate Position: in situ (1), fronted (−1). Question Type: Matrix antecedent Q (−1), Embedded antecedent Q (1).

Random effects: by-participant intercept (SD = 0.425) and by-item intercept (SD = 0.657).

To further investigate the interaction, we ran post hoc analyses using the emmeans package in R (Lenth Reference Lenth2021). There was a significant difference between fronted and in situ predicates in the matrix question conditions (![]() $\beta$ = −1.178, SE = 0.383, z = −3.078, p < 0.01*, Bonferroni corrected). Thus, in the matrix antecedent question conditions, rates of incorrect ‘Yes’ answers are higher for the wh-fronted predicate than the in situ predicate. In contrast, in the embedded subject antecedent conditions, the difference between the two predicates did not reach significance (

$\beta$ = −1.178, SE = 0.383, z = −3.078, p < 0.01*, Bonferroni corrected). Thus, in the matrix antecedent question conditions, rates of incorrect ‘Yes’ answers are higher for the wh-fronted predicate than the in situ predicate. In contrast, in the embedded subject antecedent conditions, the difference between the two predicates did not reach significance (![]() $\beta$ = 0.533, SE = 0.371, z = 1.439, p = 0.150, Bonferroni corrected: p = 0.30). This suggests that the interaction between Question Type and Predicate is driven by the matrix subject antecedent questions: participants are more likely to choose the ungrammatical antecedent in the wh-fronted conditions than the in situ conditions.

$\beta$ = 0.533, SE = 0.371, z = 1.439, p = 0.150, Bonferroni corrected: p = 0.30). This suggests that the interaction between Question Type and Predicate is driven by the matrix subject antecedent questions: participants are more likely to choose the ungrammatical antecedent in the wh-fronted conditions than the in situ conditions.

2.2.4 Discussion of experiment 1b

Experiment 1b found that matrix subject antecedents in wh-predicate fronting conditions were more likely to be chosen than in predicate in situ conditions. In light of Omaki (Reference Omaki2010) and Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019)'s findings that the processor retrieves the matrix antecedent in wh-predicate constructions, we interpret the results in Experiment 1b as reflective of this online processing routine, a common finding in offline measures. The rate of selecting ungrammatical interpretations (10%) was significantly higher than the baseline in situ cases which do not prompt readers to engage in a non-structural search.Footnote 9

2.3 Discussion of experiments 1a and 1b

Experiment 1a offers a hint that the online retrieval of a non-structurally guided antecedent search affects comprehension. Experiment 1b further supports this interpretation: readers were more likely to choose an ungrammatical antecedent for the reflexive in fronted wh-predicates than in situ ones. The fact that online processing has effects in offline comprehension is not surprising, but we might not have expected to easily find offline effects if the retrieved matrix subject were quickly abandoned. This prompts questions about the re-analysis process that readers undertake when they do arrive at the grammatically licensed interpretation. If the suggestion that readers might readily abandon a matrix construal in the predicate cases is on the right track, we expect to find strong evidence of a persistent search as early as the embedded subject. In Experiment 2, we conducted a self-paced reading experiment probing the extent to which processor persists, following Giskes and Kush (Reference Giskes and Kush2021), in an antecedent search. Further, we asked whether reflexives in wh-predicates differed from those in wh-arguments. In the former case, the search must continue if the reflexive is to find a grammatical antecedent. In the latter case, since a matrix antecedent is a grammatical, structurally-sanctioned option, the search could in principle halt if comprehenders settle on a matrix interpretation, something we have seen them doing roughly half the time in a comprehension study (Experiment 1a).

3. Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we investigated whether and how soon the processor continues to search for an antecedent by manipulating the gender of an accessible antecedent downstream from the reflexive. If the processor recognizes early that it has retrieved a potentially ungrammatical antecedent in a non-structurally guided way, as in wh-predicate constructions, we expect a GMME when the processor encounters a gender-mismatched embedded subject, as in (12a).Footnote 10 In contrast, in wh-argument cases like (12b), since a matrix antecedent is grammatical and the result of a structurally guided retrieval, the processor has no reason to seek a new antecedent. Experiment 1a showed that such an antecedent is chosen roughly half the time. In those cases, one hypothesis is that the processor will halt a search for an antecedent half the time. The magnitude of the GMME would then be attenuated in comparison to the wh-predicate condition, where a persistent search is required by the grammar.

(12)

a. Alice

$\ldots$ [

$\ldots$ [ $_{wh-pred}$

$_{wh-pred}$  $\ldots$herself

$\ldots$herself $\ldots$ ]

$\ldots$ ]  $\ldots$ the man

$\ldots$ the manb. Alice

$\ldots$ [

$\ldots$ [ $_{wh-arg}$

$_{wh-arg}$  $\ldots$herself

$\ldots$herself $\ldots$ ]

$\ldots$ ]  $\ldots$ the man

$\ldots$ the man

An alternative possibility for the wh-argument conditions is that comprehenders do not commit at these early stages to resolving the reflexive to a matrix antecedent; given the possible grammatical ambiguity, the processor may ‘wait’ to assess an alternative antecedent. In that case, we expect a GMME in wh-argument cases on par with that in the wh-predicate conditions. We consider this hypothesis less likely: we know of no evidence that downstream mismatching noun phrases pose difficulty if a preceding noun phrase provides a suitable antecedent.

3.1 Materials

The stimuli in Experiment 2 cross two two-level factors, as shown in (13). One was Phrase Type, with either a wh-argument or a wh-predicate containing a reflexive. The other factor, Gender, manipulated whether the reflexive matched or mismatched either the gender of the matrix or embedded subject. In the MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch condition, the reflexive matched the matrix subject but mismatched the downstream embedded clause subject in gender. In the MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch condition, the reflexive mismatched the matrix subject but matched the downstream embedded clause subject. (The regions used for the moving-window self-paced reading presentation are numbered and divided by slashes.)

(13) Experiment 2 stimuli: Phrase Type

$\times$ Gender

$\times$ Gender

a. wh-argument, MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch

/

$_1$ Alice wondered /

$_1$ Alice wondered / $_2$ which story /

$_2$ which story / $_3$ about himself /

$_3$ about himself / $_4$ the grumpy /

$_4$ the grumpy / $_5$ old man /

$_5$ old man / $_6$ at the pub /

$_6$ at the pub / $_7$ said /

$_7$ said / $_8$ that he /

$_8$ that he / $_9$ would tell /

$_9$ would tell / $_{10}$ at the event.

$_{10}$ at the event.b. wh-argument, MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch

/

$_1$ Alice wondered /

$_1$ Alice wondered / $_2$ which story /

$_2$ which story / $_3$ about herself /

$_3$ about herself / $_4$ the grumpy /

$_4$ the grumpy / $_5$ old man /

$_5$ old man / $_6$ at the pub /

$_6$ at the pub / $_7$ said /

$_7$ said / $_8$ that he /

$_8$ that he / $_9$ would tell /

$_9$ would tell / $_{10}$ at the event.

$_{10}$ at the event.c. wh-predicate, MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch

/

$_1$ Alice wondered /

$_1$ Alice wondered / $_2$ how sure /

$_2$ how sure / $_3$ of himself /

$_3$ of himself / $_4$ the grumpy /

$_4$ the grumpy / $_5$ old man /

$_5$ old man / $_6$ at the pub /

$_6$ at the pub / $_7$ said /

$_7$ said / $_8$ that he /

$_8$ that he / $_9$ would be /

$_9$ would be / $_{10}$ at the event.

$_{10}$ at the event.d. wh-predicate, MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch

/

$_1$ Alice wondered /

$_1$ Alice wondered / $_2$ how sure /

$_2$ how sure / $_3$ of herself /

$_3$ of herself / $_4$ the grumpy /

$_4$ the grumpy / $_5$ old man /

$_5$ old man / $_6$ at the pub /

$_6$ at the pub / $_7$ said /

$_7$ said / $_8$ that he /

$_8$ that he / $_9$ would be /

$_9$ would be / $_{10}$ at the event.

$_{10}$ at the event.

The MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch conditions were included to replicate the original Omaki finding. The MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch conditions are designed to probe whether an antecedent search persists, and whether this potential search differs between reflexives in arguments and predicates.

To ensure that all sentences were grammatical and that participants could find an antecedent for the reflexive in the sentence, we added an additional embedded clause which always contained a subject that matched the reflexive in gender. To control for any inherent differences between lexical items, we manipulated the gender of the reflexive and not that of the matrix or embedded subjects.

Twenty-eight filler items were used. Twelve filler items were adapted from Frazier and Rayner's (Reference Frazier and Rayner1982) late/early closure items. Sixteen other fillers were constructed to be similar in length to the test items and contained reflexives, pronouns, and different types of embedding structures (including wh-predicates and arguments).

Yes-no comprehension questions were asked after half of the experimental items and after 16 out of 28 filler items.

3.2 Participants and procedures

Eighty participants who did not complete Experiments 1a and 1b were recruited on Prolific.ac and redirected to the experiment on Ibex Farm (Drummond Reference Drummond2013). Three participants were excluded from the final analyses: one participant was excluded because they answered two attention check questions incorrectly and two participants were excluded because they scored less than 50% on the comprehension questions across the whole experiment. Our final analyses will report the results from 77 participants, all living in the United States and self-reported native speakers of English. Participants were paid £2.25 upon completing the experiment.

Twenty-four item sets as in were distributed over four lists in a Latin-square design. For the filler items taken from Frazier and Rayner (Reference Frazier and Rayner1982), two lists were created and distributed across the four lists. The remaining sixteen filler items were the same across lists. Before removing outlying participants, twenty participants were run on each list of stimuli. Order of presentation was pseudo-randomized such that participants saw no more than one experimental item in a row.

After being directed to Ibex Farm, participants were instructed that they would be reading sentences presented in “chunks” illustrated by the regions in (13). They were asked to read each region and press the space bar to see the next region. For test items, each item was separated into 10 regions. The number of regions in filler items ranged from 8 to 10. Participants were also instructed that after some of the items, they would be asked a yes-no comprehension question. Comprehension questions occurred after half of the experimental items. Before beginning the experiment, participants provided informed consent, answered a short demographic survey and answered two attention check questions. After completing the experiment, they answered three additional attention check questions.

We used the moving window self-paced reading paradigm (Just et al. Reference Just, Carpenter and Woolley1982). Items appeared as a series of dashed lines. Participants pressed the space bar to reveal each region in the sentence. As a new region appeared, the previous region disappeared. The time between participants’ space bar presses were recorded and serve as their reading times for each region. If there was a comprehension question associated with the item, it appeared after participants had finished reading the sentence. They were asked to choose either “yes” or “no” in response to the question, using radio buttons presented horizontally. They were provided with feedback after answering the question. If there was no question associated with the item, participants pressed the space bar to move on to the next item. The experiment began with two practice items to get participants used to the task. The experiment took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

3.3 Predictions

We outline our predictions for two regions of interest.

3.3.1 Region 3: Reflexive region

Following Omaki (Reference Omaki2010), we predicted a gender mismatch effect at the reflexive region (about himself) in both argument and predicate conditions. Thus, we predict a main effect of (matrix subject) Gender such that MatrixMismatch sentences will read more slowly than MatrixMatch in this region.

3.3.2 Region 5: Critical embedded subject region

Predictions for reading times at the embedded subject (old man), where the gender of the embedded subject is revealed, differ based on whether the processor continues searching for an antecedent even after linking the reflexive to the matrix subject. One possibility is that the processor does not re-engage in an antecedent search as early as the embedded subject in either the argument or predicate conditions, and we do not expect to find a GMME. Alternatively, as Giskes and Kush (Reference Giskes and Kush2021) show from cataphoric pronouns, the processor may be persistent in a searching for an antecedent. In the case of the predicate conditions, since the matrix antecedent cannot serve as a grammatical licensor, we expect the processor to continue searching for an antecedent and therefore register a GMME at the embedded subject. In the wh-argument conditions, a matrix antecedent is a grammatical option and in Experiment 1a we saw it was ultimately chosen half of the time. We might expect then that on enough trials the search for an antecedent will halt and therefore we expect the magnitude of the GMME to be mitigated in the wh-argument conditions compared to the wh-predicate conditions. That is, we expect an interaction, such that there are GMME effects in both predicate and argument conditions but a greater difference in reading times between EmbeddedMatch and EmbeddedMismatch in the predicate conditions than the argument conditions.

3.4 Results

3.4.1 Statistical analyses

We ran linear mixed effects regression models on the reading time data. To normalize the data, we log-transformed the reading times. We present here the log reading time results. Our models included fixed effects for Gender (Matrix/Embedded Match/Mismatch) and Phrase Type (argument or predicate), which were sum-coded. MatrixMatch was coded as 1 and MatrixMismatch was coded as -1. Argument was coded as 1 and Predicate was coded as -1. We included random intercepts for participants and items (Pinheiro and Bates Reference Pinheiro and Bates2000; Baayen Reference Baayen2008; Baayen et al. Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008), as implemented in the lme4 package (version 1.1-26, Bates and Sarkar Reference Bates and Sarkar2007; Bates et al. Reference Douglas, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (version 4.0.4, R Core Development Team, 2021). Random slopes by participants and items did not improve model fit. We used the BOBYQA algorithm for model optimization on all models. In an effort to reduce skewness, data points that were +/- 2.5 SDs from the residual error of the linear model were removed (Baayen and Milin Reference Baayen and Milin2010). Models were then refitted. We report the final fitted models. Model trimming resulted in a maximum loss of 3% of the data, across models.

We also initially fitted models containing the interaction term for our two fixed effects (Gender and Phrase Type). If an interaction in the model did not reach significance, we report the data for the fixed effects from a model containing main effects only.

Prior to analysis and data transformation, we removed any reading times below 90 ms and above 3000 ms for all data collected (including fillers). This resulted in a loss of 0.74% of the data.

Reading time results

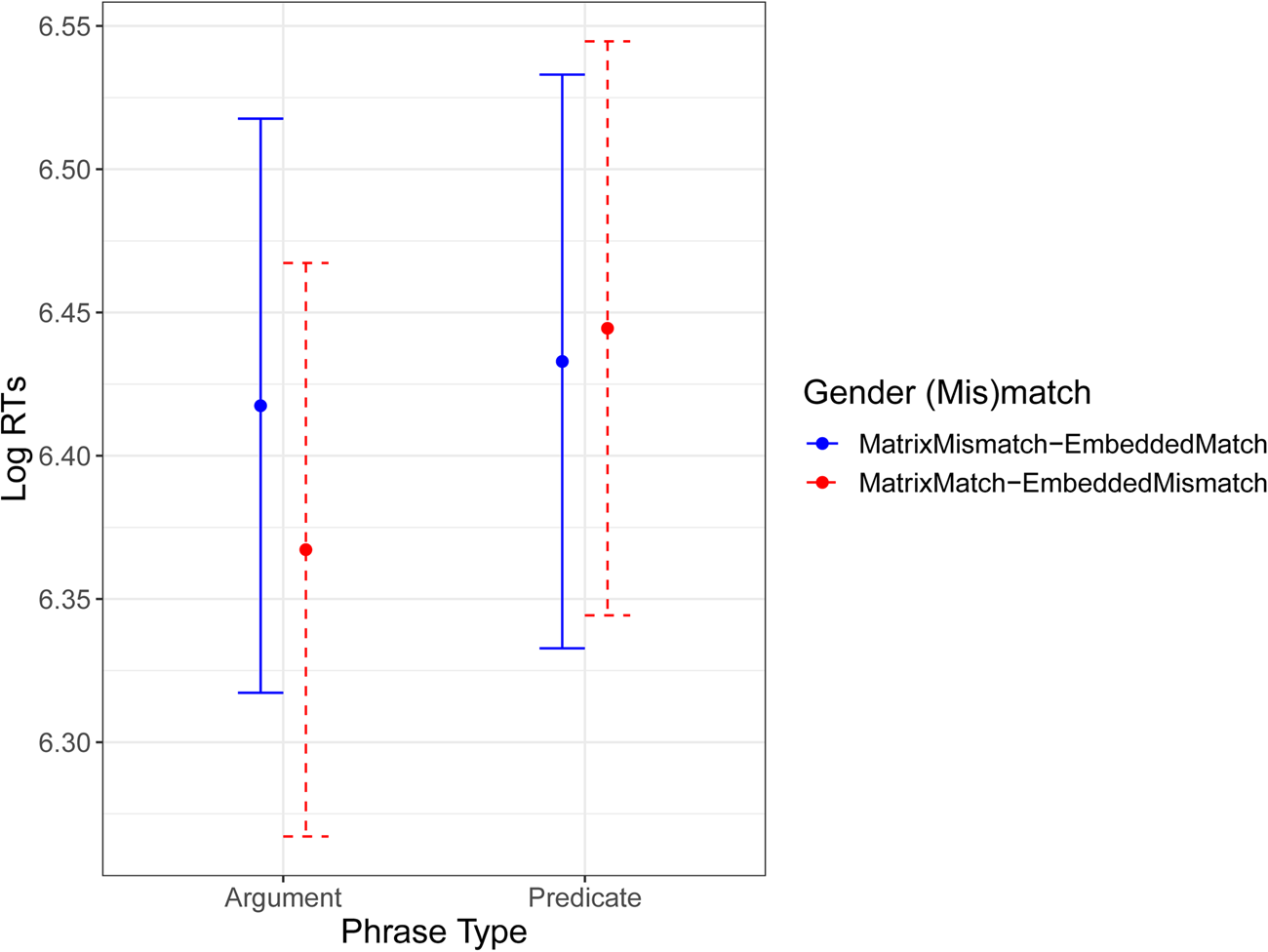

Figure 1 illustrates log reading times by region. We report the statistical analyses for regions where significant effects were found.

Figure 1. Log reading times by region in Experiment 2. The critical regions are shown in the grey box. Error bars represent standard error.

Region 3: Reflexive region

At the reflexive region (Region 3, about himself), we observed a significant main effect of Gender of the matrix subject. More precisely, processing difficulty (longer reading times) was observed when the matrix subject mismatched the reflexive in gender (![]() $\beta$ = −0.04, SE = 0.008, t = −5.112, p < 0.001***). There was no main effect of Phrase Type (

$\beta$ = −0.04, SE = 0.008, t = −5.112, p < 0.001***). There was no main effect of Phrase Type (![]() $\beta$ = 0.003, SE = 0.008, t = 0.394, p = 0.693). The model with an interaction term did not reach significance.

$\beta$ = 0.003, SE = 0.008, t = 0.394, p = 0.693). The model with an interaction term did not reach significance.

Region 4: Post-reflexive region

At the post-reflexive region (region 4, the grumpy), there was a main effect of Gender (![]() $\beta$ = −0.05, SE = 0.007, t = −7.327, p < 0.001***) but there was no main effect of Phrase Type (

$\beta$ = −0.05, SE = 0.007, t = −7.327, p < 0.001***) but there was no main effect of Phrase Type (![]() $\beta$ = 0.006, SE = 0.007, t = 0.851, p = 0.395). The model with an interaction term did not reach significance.

$\beta$ = 0.006, SE = 0.007, t = 0.851, p = 0.395). The model with an interaction term did not reach significance.

Region 5: Critical embedded subject region

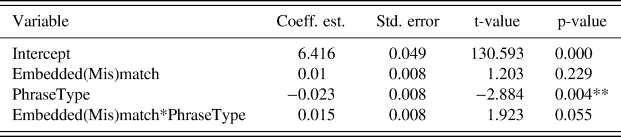

At the critical Region 5Footnote 11, where the gender of embedded subject is revealed (e.g., old man), there was a marginal interaction between Embedded (Mis)match and Phrase Type, as plotted in Figure 2Footnote 12 and reported in Table 5.

Figure 2. Matrix (Mis)match * Phrase Type Interaction plot for Region 5 (embedded subject, old man) in Experiment 2. Values taken from fitted linear mixed effects regression model. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Table 5. Final mixed-effects model for Region 5, the critical embedded subject region (N = 1786 after trimming), reported as the regression coefficient estimates, standard errors, t-values and p-values. Sum coding.

Random effects: by-participant intercept (SD = 0.332) and by-item intercept (SD = 0.149).

To further investigate the interaction, we ran post hoc analyses using the emmeans package in R (Lenth Reference Lenth2021). In wh-argument conditions, MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch were read longer than MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch conditions (![]() $\beta$ = 0.05, SE = 0.022, t = 2.213, p = 0.027, Bonferroni corrected: p = 0.05). In contrast, in wh-predicate conditions, there was no significant differences between MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch and MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch (

$\beta$ = 0.05, SE = 0.022, t = 2.213, p = 0.027, Bonferroni corrected: p = 0.05). In contrast, in wh-predicate conditions, there was no significant differences between MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch and MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch (![]() $\beta$ = −0.012, SE = 0.023, t = −0.509, p = 0.611, Bonferroni corrected: p = 1). The interaction was driven by the fact that the argument MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch conditions were actually read faster than the other three conditions. The predicate conditions were read equally fast.

$\beta$ = −0.012, SE = 0.023, t = −0.509, p = 0.611, Bonferroni corrected: p = 1). The interaction was driven by the fact that the argument MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch conditions were actually read faster than the other three conditions. The predicate conditions were read equally fast.

Region 6: Embedded subject spillover region

In Region 6, the region after the gendered head noun is revealed (e.g., at the pub), we found main effects of both Gender and Phrase Type. MatrixMatch-EmbeddedMismatch conditions showed longer reading times compared to the MatrixMismatch-EmbeddedMatch conditions (![]() $\beta$ = −0.022, SE = 0.007, t = −3.409, p < 0.001***) and predicate conditions were read longer than argument conditions (

$\beta$ = −0.022, SE = 0.007, t = −3.409, p < 0.001***) and predicate conditions were read longer than argument conditions (![]() $\beta$ = −0.022, SE = 0.007, t = −3.39, p < 0.001***). The model containing an interaction term between these two fixed effects did not reach significance. The main effect shows a GMME regardless of Phrase Type, suggesting that in both predicate and argument conditions, the processor persists in its antecedent search.

$\beta$ = −0.022, SE = 0.007, t = −3.39, p < 0.001***). The model containing an interaction term between these two fixed effects did not reach significance. The main effect shows a GMME regardless of Phrase Type, suggesting that in both predicate and argument conditions, the processor persists in its antecedent search.

3.5 Discussion

First, Experiment 2 replicated the effect discovered in Omaki (Reference Omaki2010), whereby reflexives in both wh-argument and wh-predicate phrases exhibit a GMME with respect to the matrix subject. The novel manipulation we introduced in Experiment 2 probed whether the processor continues to search for an antecedent, and whether this differs between predicates and arguments. We did find evidence of a persistent search at the embedded subject spillover region (the PP following the gendered head noun, Region 6); there we found a GMME driven by slow reading times when the reflexive mismatched the embedded subject. This was a main effect, holding for both predicate and argument conditions. This result fails to bear out a plausible hypothesis that there would be an interaction, whereby the GMME would be mitigated in argument wh-phrases since the matrix subject is a viable antecedent and this could halt the search for an antecedent downstream. The lack of an interaction suggests that even when one grammatical antecedent is retrieved, that does not preclude further retrieval of accessible antecedents downstream. This is a striking result given that the argument cases are being compared to instances where readers must retrieve the embedded subject as an antecedent. Nonetheless, the strength of the GMME does not differ (no interaction).

We found a main effect of Phrase Type in Region 6, the embedded subject spillover region, which could be due to the greater complexity in processing a predicate rather than an argument. Unlike the argument, the predicate has a experiencer theta role to discharge. Although we do not yet know the mechanisms by which this happens in fronting constructions, this may increase reading times, particularly when a candidate argument (the embedded subject) is encountered and thus integrated into the thematic representation.

One finding that we did not predict was the (marginal) interaction at the embedded subject head noun region (Region 5, the critical region that signals the gender of the embedded subject). We found an interaction but not of the shape predicted (see Figure 2). That is, there was no mismatch effect with respect to the embedded subject (the content being read in that very region), although it is not unusual that such an effect would not appear right here but on the following spillover region (which it did). Rather, the interaction we found suggests a hangover effect of the matrix subject mismatch, although only for wh-arguments. That is, the numerical trends suggest that the wh-argument conditions were read faster when a gender-matching matrix antecedent had been encountered than when a gender mismatching matrix antecedent had been. No such lingering difference from the matrix subject is apparent in the wh-predicate conditions in this region. This is consistent with the findings in Omaki Reference Omaki2010 and Omaki et al. Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019 that also showed that the effect was more short-lived for predicates than for wh-arguments. One possible interpretation for this difference could rest on the greater strength of comprehenders’ commitments to (or retrieval of) the matching matrix subject in the wh-argument as compared to the wh-predicate conditions. By this region, it appears that there is no advantage for wh-predicates in having found a matched matrix subject. Since the backward retrieval of that antecedent is not structurally guided, the processor may very quickly abandon such a construal and be prepared to seek another antecedent, which is consistent with suggestions in Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) from their Experiment 2. However, this difference does not translate in our data to a different reaction to the mismatched embedded subject, which makes the lack of the expected interaction all the more surprising. The apparent advantage that reflexives gain in having found a viable, structurally sound antecedent in wh-arguments does not mitigate the effects of encountering a mismatched noun phrase afterwards.

4. General Discussion

In three experiments we examined the interpretation and processing of reflexives that can be characterized, following Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019), as initiating a non-structural search for an antecedent. These are instances of reflexives housed in fronted wh-predicates. Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) found evidence that these reflexives retrieved antecedents in ways that are not constrained by structural factors, like c-command. They suggest that it is the absence of structure, coupled with the strong pressure to locate an antecedent for the reflexive, that prompts such a non-structural search. Our studies bear on two issues: the role of non-structural search in comprehension, and whether reflexives in these contexts trigger a persistent search in the sense of Giskes and Kush (Reference Giskes and Kush2021).

Non-structural search and comprehension

Our studies investigated whether the results of this search affected offline comprehension, in spite of the fact that such antecedents cannot alone provide the reflexive with a grammatical binding antecedent. In Experiments 1a and 1b, we found evidence that antecedent retrievals that are not structurally guided have effects on the offline interpretation of sentences. There was suggestive evidence – in the reading studies reported in Omaki (Reference Omaki2010), Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019) and our Experiment 2 – that such antecedents might be quickly abandoned by the processor. It appears, however, that non-structurally guided antecedents are entertained as viable antecedents robustly enough that readers will commit to them in reflective judgments, even when such interpretations are not grammatical given the content of the sentence as a whole. Experiment 1b suggested that these ungrammatical construals were directly tied to the particular configuration that gives rise to a non-structurally guided search: reflexives in fronted predicates allowed for ungrammatical construals significantly more than ungrammatical construals of reflexives in predicates that were not moved (in situ). These results do not suggest that antecedents retrieved under non-structural guidance are particularly tenuous.

Persistent search

Our self-paced reading results are informative in light of recent findings about persistent search. Giskes and Kush (Reference Giskes and Kush2021) argue that like wh-fillers, cataphoric pronouns initiate an active search for an antecedent (Kazanina et al. Reference Kazanina, Lau, Lieberman, Yoshida and Phillips2007; Pablos et al. Reference Pablos, Doetjes, Ruijgrok and Cheng2015; Drummer and Felser Reference Drummer and Felser2018). Our results suggest that persistent search is not limited to cataphora, nor, surprisingly, to cases where an initial retrieval resulted in failure. Contrary to our expectations, reflexives in wh-arguments behave just as the reflexives in wh-predicates at the embedded subject position, despite the fact that in the latter an antecedent is required whereas in the former it is fully consistent with the grammar that no antecedent be found.

Going into the study, we assumed that anaphors that retrieve (and presumably) resolve to grammatically sanctioned antecedents do not launch a further search. Indeed, to our knowledge, there is no comparable finding in the cataphora literature in which downstream mismatches trigger disruption after a suitable antecedent is found. For instance, van Gompel and Liversedge (Reference van Gompel and Liversedge2003)'s cataphoric sentences included mismatched objects following matched subjects in the main clause (e.g., When she was fed up, the girl visited the boy very often), but they report no effect of mismatch at the object, even though in principle co-reference could hold between the cataphor and the object. The wh-argument cases we examined (like (14)) differ, of course, from pronominal cataphora along a number of dimensions.

(14) Andrew

$_i$ wondered which picture of himself

$_i$ wondered which picture of himself $_i/{}_j$ Roger

$_i/{}_j$ Roger ${}_j$ saw.

${}_j$ saw.

First, they involve a combination of backward (cataphoric) and forward (anaphoric) searches. Second, the reflexive is contained within a so-called picture noun phrase, which introduces various subtle pragmatic and perspectival requirements (Kaiser et al. Reference Kaiser, Runner, Sussman and Tanenhaus2009). Perhaps most crucially, however, the reflexive is contained in a wh-phrase which itself signals that there will be an upcoming gap in which the reflexive can be interpreted (Chapman Reference Chapman2018; Frazier et al. Reference Frazier, Bernadette and Charles1996). It is possible that engaging in a search for a gap prompts the processor to reconsider options for the reflexive that are structurally appropriate: the gap site will necessarily be in the c-command domain of the embedded subject and, given the Active Filler Strategy (Frazier Reference Frazier1987), likely in the same clause as the upcoming subject, making that an accessible antecedent according to Principle A (Frazier et al. Reference Frazier, Bernadette and Charles1996). If this is indeed the explanation for the surprising persistent search we found for reflexives in wh-arguments, then we might expect that without an overt signal of wh-movement, the persistent search will not arise. This could in principle be tested by comparing reflexives in fronted wh-phrases like our stimuli, as in (15a), to reflexives inside the head noun phrase of a relative clause, as in (15b).

(15)

a. Min heard which story about herself the grumpy old man told.

b. Min heard the story about herself the grumpy old man told.

While reflexives in relative clause heads such as (15b) can be licensed by both the matrix subject or by a lower subject when reconstructed into the gap position of the relative (Schachter Reference Schachter1973; Vergnaud Reference Vergnaud1974), at the point of processing the reflexive, the processor does not have any evidence for a relative, and hence not for a gap site. Thus unlike in (15a), in (15b) there is no active search initiated by a wh-filler. We expect that the GMME at the embedded subject in (15a), which we found in Experiment 2, would not be duplicated in (15b). Frazier et al. (Reference Frazier, Ackerman, Baumann, Potter and Yoshida2015) have independently shown that reflexive antecedent search is sensitive to the structures that arise when wh-fillers are represented at their gap sites. If our predictions regarding (15) bear out, it may be the case that reflexive antecedent search and wh-filler dependencies are tightly connected. In this sense, the surprising persistent antecedent search we found may arise parasitically on wh gap-filling processes.

5. Conclusion

In three experiments we investigated the interpretation and processing of sentences where reflexives engage in a non-structurally guided search, as identified by Omaki et al. (Reference Omaki, Ovans, Yacovone and Dillon2019). We found that antecedents retrieved this way, while potentially ‘fleeting’ in processing, can impact comprehension in reflective tasks. We then sought to determine if and how quickly the processor engages in further search. This question is particularly interesting in the case of wh-argument constructions, where the reflexive can resolve grammatically to the matrix antecedent. It is not grammatically required that the processor continue to search for an antecedent in those cases, and indeed we found that our participants committed to a matrix antecedent roughly half of the time when asked about their interpretation of the entire sentence. The self-paced reading results showed, however, that the processor continues to search for an antecedent for a reflexive found in both wh-predicates (where this is required) and wh-arguments. We suggested that these surprising persistent searches may be due to the reflexive being contained in a wh-filler, which prompts a parasitic forward search. It seems that second chances are available to reflexives, whether they need them or not.