Introduction

Patients who are diagnosed with terminal illness or end-stage disease are often confronted with multiple losses across their illness trajectory, ranging from the loss of identity and relationships to the loss of hope and meaning in life; these feelings of loss are exacerbated by experiences of existential and spiritual suffering encountered in anticipation of their mortality (Boston et al. Reference Boston, Bruce and Schreider2011). Nevertheless, the knowledge of their impending death provides terminally ill patients with opportunities to process their perceived losses and suffering, thus leading to feelings of acceptance and inner peace at life’s end (Goldsteen et al. Reference Goldsteen, Houtepen and Proot2006; Montoya-Juarez et al. Reference Montoya-Juarez, Garcia-Caro and Campos-Calderon2013).

Mindfulness and its application in palliative care

The past 3 decades have seen a proliferation of research into the benefits of mindfulness in coping with suffering or painful thoughts and emotions (Neff and Germer Reference Neff and Germer2012). By definition, mindfulness involves paying attention to one’s moment-to-moment experience and relating to it with curiosity and acceptance (Shapiro et al. Reference Shapiro, Carlson and Astin2006). According to Shapiro et al. (Reference Shapiro, Carlson and Astin2006), the 3 fundamental components of mindfulness are intention (purpose of practicing mindfulness), attention (one’s observation of their experiences), and attitude (personal qualities that facilitate mindfulness practice). These interwoven components occur simultaneously in a single cyclic process and facilitate significant shifts in perspectives, enabling one to view moment-to-moment experiences with greater clarity and objectivity (reperceiving). Through reperceiving, one is better able to process and cope with their suffering and emotional pain (Shapiro et al. Reference Shapiro, Carlson and Astin2006).

Given its potential in alleviating emotional distress and promoting well-being, mindfulness has been incorporated in palliative care provision to help cancer patients cope with illness- and death-related anxiety by directing their attention to present-moment reality and to their bodily sensations without judgment (e.g., Haller et al. Reference Haller, Winkler and Klose2017; Shennan et al. Reference Shennan, Payne and Fenlon2011; Tacón Reference Tacón2011; Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Burrell and Jordan2018). While the existing literature has shown the benefits of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in promoting cancer patients’ well-being, very few studies involve terminally ill patients who face greater existential challenges coping with their impending death. Of these studies, the effectiveness of MBIs in alleviating terminally ill patients’ psychological distress and emotional suffering varies due to feasibility issues (e.g., intervention duration, delivery setting) (Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Burrell and Jordan2018). Therefore, adaptations to MBIs are required to better support the terminally ill population, instead of indiscriminate application as a general “cure-all” therapeutic technique.

Mindfulness as dignity-conserving practice for terminally ill

One of the overarching goals in caring for terminally ill populations is to preserve their dignity (World Health Organization 2011), as patients have described life without dignity as life no longer worth living (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002). Through in-depth interviews conducted with terminally ill patients in Canada, Chochinov et al. (Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002) developed the dignity model which elucidates 3 major categories of factors that influence patients’ sense of dignity at the end of life: illness-related issues, dignity-conserving perspectives and practices, and social interactions. In this model, one of the core dignity-conserving practices involves mindfulness, that is to focus on the present time without worrying about the future and to live from day to day (hereinafter referred to as mindful living). Subsequent research on the applicability of dignity model in the Asian community reveals that the practice of mindful living in the Chinese context is more family-centric, where patients focus on the here and now alongside their family during the final stages of their terminal illness (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Leung2013a, Reference Ho, Leung and Tse2013b). While this revelation highlights the pivotal variation of mindfulness as a dignity-conserving practice in the Asian palliative care, the components that facilitate mindful living among terminally ill patients remain unknown.

Research gap and objective

Mindfulness is deemed an effective coping mechanism against existential and spiritual suffering in anticipation of mortality (Tacón Reference Tacón2011) and is frequently exhibited as mindful living among terminally ill patients (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Leung2013a). While the axioms of mindfulness, in general, have been elucidated (Shapiro et al. Reference Shapiro, Carlson and Astin2006), the facilitating components of mindful living that promote dignified dying in the end-of-life context have yet to be explored. This study aims to review the lived experience of terminally ill patients in Singapore and explicate the mechanisms of mindful living as their death draws near. The findings will shed light on the possible directions of MBIs suited to the terminally ill population as well.

Methods

Study design

This study analyzed all 50 dyadic interview transcripts collected from a larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) which assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of a novel Family Dignity Intervention (FDI) developed for Asian palliative care. Essentially, FDI is a brief, meaning-oriented, dignity-enhancing life review intervention conducted with terminally ill patients and their family caregiver to fortify their family connectedness through facilitated expressions of love and appreciation, as well as impartation of living wisdoms for lasting legacies. The inclusion criteria, sampling methods, and intervention procedure for the FDI are comprehensively described in the protocol (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Car and Ho2017).

Participants

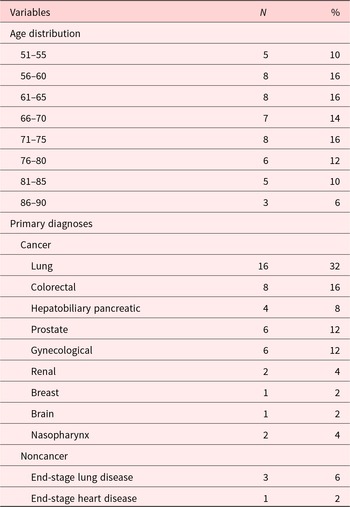

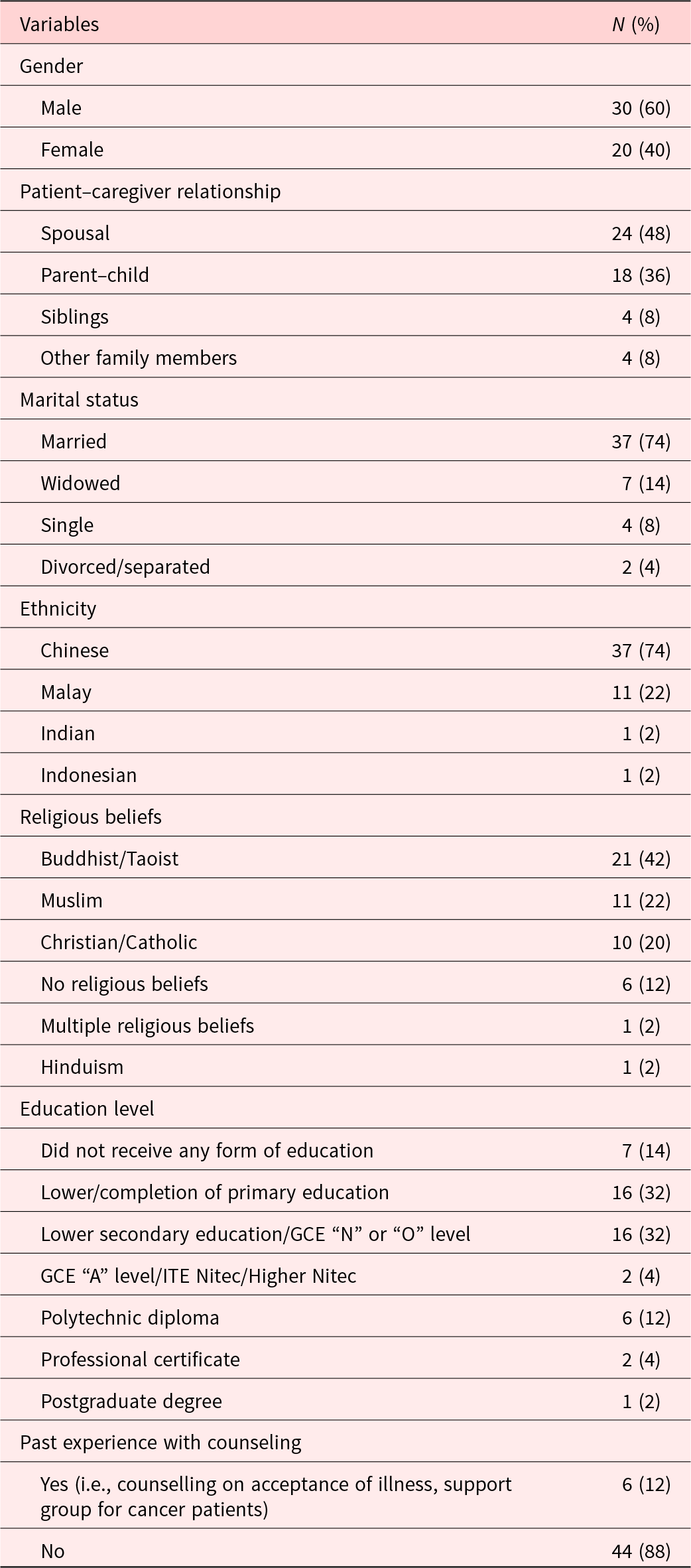

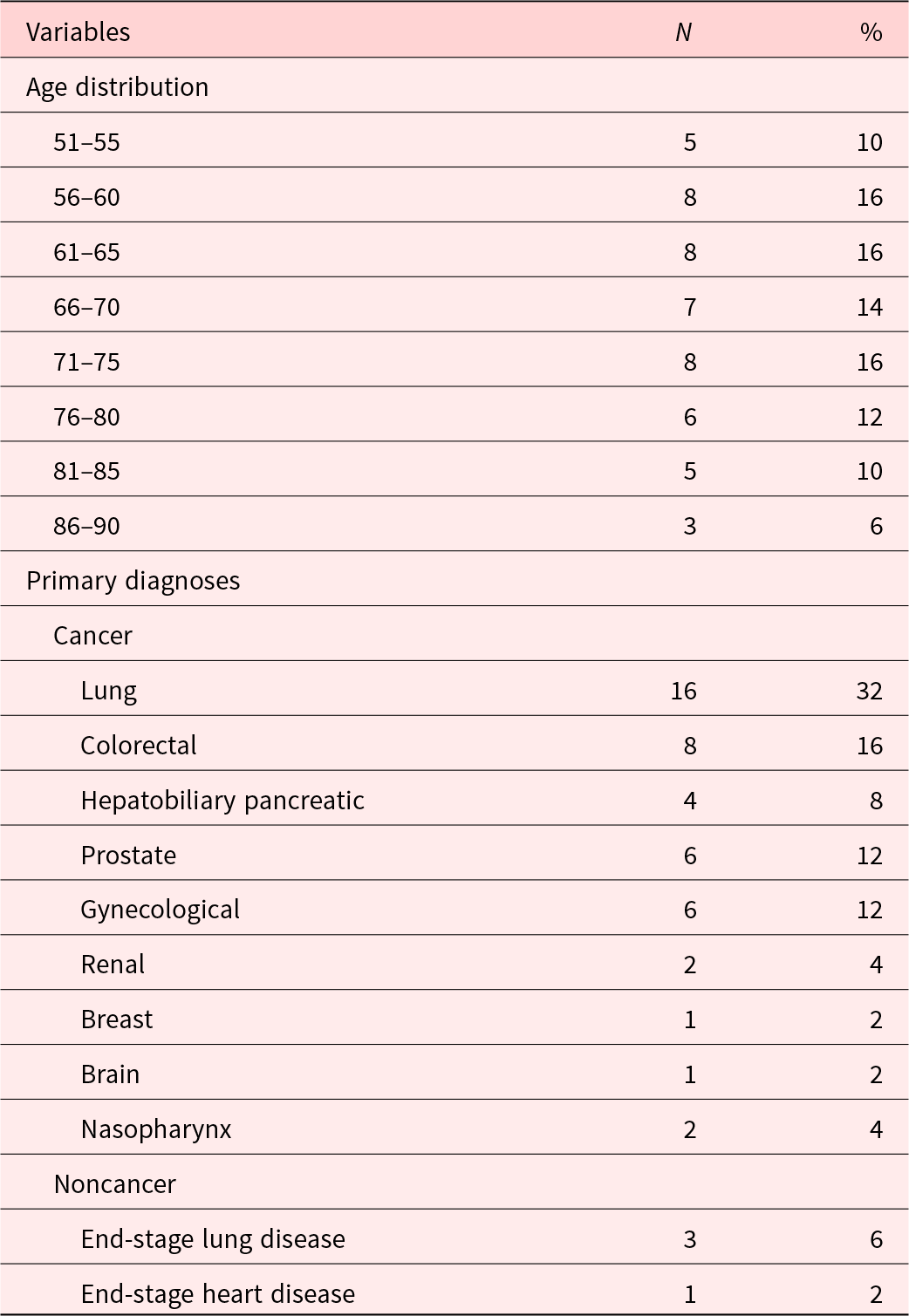

The originally proposed inclusion criteria set for participation included patients aged 60 years and above and those diagnosed with a terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than 6 months. Due to sampling difficulties and a restricted study timeline, the inclusion criteria were revised to include terminally ill patients aged 50 and above, with a prognosis of less than 12 months. The current sampling population comprised 50 patients, with a mean age of 69.33 years (SD = 10.38) and an average life expectancy of 8.12 months (SD = 3.23), who were receiving palliative care or hospice care in Singapore. Majority of the patients were Chinese males diagnosed with cancer and were either in a spousal or parent–child relationship with their primary family caregiver. Refer to Tables 1 and 2 for more demographic and medical information.

Table 1. Demographic information (N = 50)

Table 2. Patients’ life expectancy, age distribution, and primary diagnoses

Procedure

A semi-structured interview guide was used to elicit patients’ life stories in relation to their families, while shaping the focus of the interview based on their respective interests and sharing (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Car and Ho2017). Patients underwent up to two 45- to 90-minute interviews at their respective homes that were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were conducted in English, Mandarin, Malay, Cantonese, and/or Hokkien. Non-English transcripts were translated and reviewed by 2 research team members to ensure accuracy.

Data analysis

The present study adopted interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) which enabled an in-depth exploration of mindful living among terminally ill patients in Singapore (Smith and Osborn Reference Smith, Osborn, Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009). The IPA involved (a) understanding the transcripts and context of sharing, (b) line-by-line coding, (c) organizing the codes into meaningful themes, and (d) connecting the themes. Research field notes were used as supplementary information to provide contextual information of the patients’ sharing. To ensure the research rigor and trustworthiness of findings, stringent mechanisms proposed by Krefting (Reference Krefting1991) were adopted including maintenance of reflexive memo, peer debriefing, inter-researcher consensus in finalizing the coding framework and data interpretation, and investigator triangulation.

Results

Findings revealed 12 themes that were organized into 3 interwoven components of mindful living among terminally ill patients – purposive self-awareness, family-centered attention, and attitudes of mortality acceptance – forming the empirical model of mindful living for dignified dying (see Figure 1). Mindful living was observed as patients found serenity at their end of life through concurrent (a) intentional examination of their internal experience related to their illness and mortality (purposive self-awareness), (b) conscious exploration of their involvement and achievements in the family (family-centered attention), and (c) proactive arrangements in preparation for their death (attitudes of mortality acceptance). Each component and its corresponding themes play a significant role in facilitating mindful living at the end of life.

Figure 1. Empirical model of mindful living for dignified dying.

Purposive self-awareness

Patients engaged in introspection about their thoughts and emotions revolving around their illness to find resilience, meaning, and support in facing imminent death. This involved drawing strength from their faith (spiritual fortitude), balancing between fighting against and accepting their illness (fluid resiliency), retaining their connection with their community (collective interdependency), and reconstructing the narratives of their terminal illness (liberating reconciliation).

Spiritual fortitude (No. of transcripts = 38)

Patients subscribed to and derived strength from faith-based beliefs that enabled them to embrace their terminal illness and mortality as part of the life cycle and achieved serenity.

I am grateful to God. He has looked after me and helped me throughout this journey. Although we cannot see Him, we can feel His presence. That is why I am not fearful of this disease. I am at peace. (58-year-old husband, end-stage lung disease)

“Living in the here and now” was a gift and recurring source of spiritual comfort which aided terminally ill patients to embrace the finitude in life and cherish each living moment.

I just want to live in the here and now, as long as my family is safe. Our lives are destined, whether they are good or bad. […] When we’ve reached the end of our life journey and it is time to go, we have to be contented. (90-year-old mother, colorectal cancer)

Fluid resiliency (N = 32)

Patients struck a delicate balance between fighting against their illness and acknowledging death as a natural process, by which aided them to live in the here and now while engaging in death preparation.

If treatment is possible, I will go for it and take each step as it comes. After all, life is precious. […] I don’t see death and funeral planning as taboo, and I address them. Mortality is part of life, and it is only a matter of time before we die. (70-year-old mother, gynecological cancer)

Instead of being defined and constricted by their illness and mortality, patients opted to maintain normalcy in their daily living. This allowed them to retain their quality of life despite having to undergo intensive treatments.

Don’t be dejected and lost just because you have terminal illness. It has been ten over months (since my diagnosis), but I don’t see myself as a cancer patient. […] During chemotherapy, I listened to music and watch television. […] I am not restricted by my illness, and I do what I want to do. (64-year-old husband, lung cancer)

Collective interdependency (N = 20)

By remaining connected with their social groups, patients were able to attain strength and contentment in daily living, unrestricted by their illness and imminent death.

All of them are very supportive: my friends, the church people … […] I feel happy and satisfied (when they visit me). (72-year-old father, hepatobiliary pancreatic cancer)

Recognition of their membership in the community enabled patients to actively seek medical and financial support to ease their struggles and pain. With the alleviation of these stressors, patients could focus on appreciating their day-to-day experience nearing their end of life.

The social worker and homecare team are here to help you. That’s why when you have illness and pain, you must voice out. […] If not, nobody knows the challenges you are experiencing. (55-year-old father, lung cancer)

Liberating reconciliation (N = 11)

Patients embraced the losses resulting from their terminal illness by reconstructing the narratives of their experience, instead of dwelling in the sorrow of life’s finitude.

This is a new phase of my life. I take it as a blessing. […] It has helped me to re-appraise my life and the people around me. (70-year-old husband, lung cancer)

Rather than seeing their illness as the ultimate end, patients reinterpreted their impending death as a gateway to redefine their purpose of living and could cherish the remaining time they have.

Previously I was very concerned and worried about leaving my kids, but God allowed me to reflect. […] Now, I see the illness as a blessing. […] I love myself more, of what I have become because my perspectives have changed, my focus has changed. […] I am at peace with myself. (53-year-old mother, lung cancer)

Family-centered attention

Patients focused on their familial relationships, as well as their accomplishments and legacy within the family, thus leading to a deepened bond between themselves and their family members at life’s end. This involved relaying wisdom and hopes to their next of kin (unifying legacy), identifying personal achievements within their family (humble triumphs), expressing love and appreciation for their beloved family (conscious gratitude), acknowledging family’s support throughout their illness trajectory (recognizing compassion), and resolving remorse and unfinished business (forgiving grace).

Unifying legacy (N = 44)

Patients imparted important values to their family, particularly their children, in hopes of sustaining their family values and legacy after their death.

Soon, I will not be around. (After I die), I wish that my family will remain intact; the family bond must be there. (55-year-old husband, lung cancer)

When patients received assurance that their family legacy had been passed on to the next generation, they felt fulfilled and were ready to face their mortality.

I’ve told my children, ‘You have to stay connected with each other and look after one another. When you do that, I will feel comforted (on my deathbed).’ They told me, ‘We will.’ (80-year-old husband, lung cancer)

Humble triumph (N = 42)

Patients who were able to recognize and celebrate their contributions in the family acquired a profound sense of fulfilment, as they felt that they had executed their social roles that are pertinent to their identity.

I’ve raised my children with my own hands, and I’m contented with that. They are all grown up, married, and even have children of their own now. (70-year-old mother, renal cancer)

Receiving acknowledgements of their accomplishments from their family members not only provided a closure to patients’ lifelong roles and purpose but also brought them closer to one another prior to patients’ death.

It is my duty as a parent to raise my children. […] Still, I am very thankful to receive affirmation from my daughter (regarding my contribution in the family). I feel comforted. (75-year-old mother, end-stage lung disease)

Conscious gratitude (N = 39)

As death drew near, patients often wished to convey their gratitude to their family but found difficulty in articulating their feelings.

I’m not good at words of appreciation, that’s why I don’t know how to say it. […] I show it through actions. (56-year-old mother, breast cancer)

Through the FDI facilitation, patients were able to translate their appreciation into words and attain fulfilment from their cathartic expressions of love, hence deepening their relationship with their family.

I am grateful for you. […] I don’t think we have ever talked about being grateful (for each other), but I feel grateful in my heart. (80-year-old father, lung cancer)

Recognizing compassion (N = 34)

By acknowledging family members’ compassionate support in alleviating their suffering at the end of life, patients were better able to cope with their illness and appreciate every living moment.

They give me strength. That’s why I can persevere. […] My family support is very, very strong. (56-year-old mother, breast cancer)

Patients often identified compassionate familial support as blessings. This viewpoint enabled them to embrace their impermanent future.

My illness wakes me up and says, ‘You got a wonderful wife, man! How did it take you so long to notice this?’ […] I really, really appreciate my wife’s support. (77-year-old husband, prostate cancer)

Forgiving grace (N = 13)

Some patients expressed unresolved remorse which stemmed from either their past behavior or current illness. By seeking forgiveness from their family, patients made peace with themselves at life’s end.

I apologized to my children, and they accepted my apology. […] After I was diagnosed with this illness, I said to them, ‘I’m sorry for hitting you without rhyme or reason in the past. It was my fault.’ (58-year-old husband, colorectal cancer)

Patients moved toward self-forgiveness and found tranquility when they let go of the remorse stemming from their illness. This allowed them to appreciate the support they received from their family.

My husband takes great care of me since I have fallen ill. He does anything and everything, including our daily meal plans. However, I see this as a burden. […] I wish to thank him for everything he has done for me. I hope we can be together again in another life. (54-year-old wife, brain cancer)

Attitudes of mortality acceptance

Patients adopted non-judgmental attitudes toward death as they made necessary arrangements in preparation for their passing. Engaging in such planning assisted them to obtain a closure in life and cherish each living moment before their life ends. Specifically, this involved spending quality time with their family (transcendental communion), sharing their final wishes and making post-death arrangements (addressing impermanence), and entrusting their responsibilities to their next of kin (bequeathing roles).

Transcendental communion (N = 26)

Embracing the finitude of their life, patients appreciated and engaged in every present moment with their family to create more memories together before their passing.

I want to spend the remaining time with my family, where we can cook together, have meals together, spend happy moments together, and be as simple as just being with each other. (62-year-old husband, nasopharynx cancer)

These memories would then serve as mementoes of their continuing bond that transcended mortality.

I want to take more photos with my husband. […] I want him to keep our memories in his phone, so that he can look at those photos whenever he misses me (after my passing). (54-year-old wife, brain cancer)

Addressing impermanence (N = 16)

Patients proactively engaged in death preparations (e.g., setting up will and securing columbarium niche), which brought them peace and ease of mind knowing that these preparations would help their family to cope with the transition after their passing.

That is my priority: to make sure that they are all well placed (after my death), including my daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren. When I have to go, I am at ease. (70-year-old husband, lung cancer)

When patients were able to share their final wishes with their family, they achieved closure and solace at the end of life.

If I were to die, I hope my sister can lead a peaceful life without worries. I want her to be happy and visit wherever she wants to go. That is all I want for her. (57-year-old brother, end-stage lung disease)

Bequeathing roles (N = 13)

Knowing that their next of kin would be assuming their role in keeping the family together, patients were able to embrace their impending death and focus on spending quality time with their family.

I hope that my wife can continue to be strong and be a pillar for our family, to hold everything together. […] I also wish my daughter can help her in doing so. (51-year-old husband, hepatobiliary pancreatic cancer)

Patients were especially worried about their surviving spouse after their passing. After ensuring that their children would take care of their spouse, patients felt at ease and more prepared for their inevitable death.

I have told my children, ‘When I’m not longer around, you look after your mother. That’s the most important to me: you must look after your mother.’ (65-year-old husband, renal cancer)

Discussion

This is the first known study which has explicated the axioms of mindful living among terminally ill patients in the Asian context.

Mechanisms of mindful living in dignity preservation

Based on the findings, mindful living is defined as an ongoing search of solace in every living moment while appreciating one’s limited time with their family at the end of life. Similar to the axioms of mindfulness proposed by Shapiro et al. (Reference Shapiro, Carlson and Astin2006), the facilitating components of mindful living in the end-of-life context include (a) purposive self-awareness regarding one’s illness (intention), (b) conscious exploration of one’s involvement in and appreciation of their family (attention), and (c) acceptance of and proactive preparation for one’s mortality (attitude). These interweaving components form a cyclic process (see Figure 1) that facilitates reperceiving, thus enabling patients to embrace their terminal illness and inevitable death – through meaning reconstruction and the lens of gratitude – with a greater sense of dignity.

Although patients often experience existential suffering and death anxiety upon learning about their terminal illness (Boston et al. Reference Boston, Bruce and Schreider2011), they are eventually able to cope with and embrace their mortality as they practice mindful living (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Leung2013a). By engaging in purposive self-awareness with family-centered attention and nonjudgmental attitudes toward mortality, patients process their thoughts and emotions in response to their illness, appraise their lifelong accomplishments within their family, and come to an awareness of the necessary end-of-life arrangements to be made. These introspections on life and death – be they facilitated or self-initiated – allow patients to derive meaning, wisdom, personal growth, and appreciation of life (Montoya-Juarez et al. Reference Montoya-Juarez, Garcia-Caro and Campos-Calderon2013; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Breier and Depner2018). The shift in perspective then assists patients to attain tranquility, live in the here and now, and preserve their dignity (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002; Goldsteen et al. Reference Goldsteen, Houtepen and Proot2006).

Mindful living for dignified dying in the Asian culture

Given that Singapore is a multicultural society (Singapore Department of Statistics 2019), the current findings have moderatum generalization to similar Asian groups, thus providing invaluable insight into the manifestation of mindful living as a dignity-conserving mechanism among terminally ill patients in the Asian context. In the Western culture (as shown in the dignity model) (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002), mindful living is exhibited through focusing on the present moment without worrying about the future; in the Asian culture (as presented in this paper; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Chan and Leung2013a, Reference Ho, Leung and Tse2013b), addressing the impermanent future and reviewing one’s personal involvement in their family are equally important in facilitating mindful living for dignified dying.

The current findings exemplify the concept of interdependent self-construal in the Asian culture (Cross et al. Reference Cross, Hardin and Gercek-Swing2011), wherein patients define and acquire meaning of their existential purpose primarily by important relationships, particularly their family. Prior to bringing down the curtain on their lifelong roles and achievements in their family, patients execute their final responsibility (Goldsteen et al. Reference Goldsteen, Houtepen and Proot2006), that is, making pivotal arrangements to prepare their family members for the inevitable transition that ensues after their death. The dying wish of ensuring their family is “well placed” and “living in the here and now” with their beloved family is reiterated across the narratives, underpinning the family-centric processes in mindful living for dignified dying.

Clinical implications

To better support and promote mindful living among terminally ill patients in the Asian culture, health-care providers can consider the following recommendations.

MBIs and mindfulness practice

MBIs and mindfulness practice can move beyond the conventional approach of drawing attention to somatic and sensory experience to focus on patients’ thoughts and emotions arising from their illness trajectory and in anticipation of their imminent death. Through such introspection, patients can recognize, process, reperceive, and embrace their varied experiences – pleasant and unpleasant – in their mindful living journey. Given the importance of family-centric processes in mindful living among Asian terminally ill patients, family-based MBIs and mindfulness practice can also be developed to facilitate the integration of mindfulness in their everyday life and interactions with families at life’s end.

Family-centered life review interventions

Meaning-oriented life review interventions that involve both patients and family members, such as FDI (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Car and Ho2017), can be incorporated into existing social work services to (a) affirm patients’ lifelong roles and contributions within their family, (b) facilitate heartfelt sharing between patients and their family, and (c) bring closure to patients’ unresolved remorse and/or unfinished business associated with their family. The conscious exploration of their involvement in and relationship with their families helps to bring closure to their lifelong commitment, thus enabling them to find solace and live in the here and now at the end of life.

Advance care planning

As discussed earlier, addressing the impermanent future is crucial in facilitating mindful living among Asian terminally ill patients as their death draws near. As such, advance care planning can be adopted to (a) address patients’ final responsibilities (e.g., entrusting roles to their next of kin), (b) make necessary post-death arrangements (e.g., setting up will), and (c) specify their hopes and wishes for themselves and their family (e.g., how they want to spend their remaining time), in addition to planning for health-care options. Knowing that their family is well placed and that they have fulfilled their final responsibilities, patients can then focus on their moment-to-moment experience with their family in their final days.

Limitations and research directions

The current findings lay important groundwork for a better understanding of mindful living among terminally ill patients in the Asian community, and possible directions for the incorporation of mindfulness in interventions catered to their needs. As the analysis was based on interview transcripts drawn from a larger RCT (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Car and Ho2017), more comprehensive research is recommended to (a) elucidate the development of mindful living across patients’ illness trajectory, (b) examine the generalizability of the current findings to other Asian communities, and (c) develop and evaluate MBIs suited to the unique needs of terminally ill patients.

Conclusion

Based on our findings, mindful living is a dignity-conserving quest of acquiring serenity while embracing one’s impending death at life’s end. Through mindful living, terminally ill patients safeguard their dignity and inner peace when confronted with imminent death. In essence, mindful living is not the end product of mindfulness practice but an ongoing inner journey of reviewing one’s bittersweet past, accepting the present situation, and anticipating the impermanent future while searching for tranquility and mortality acceptance.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

AHYH conceived the study, obtained funding, supervised the research team, and oversaw study implementation. PYC, GTH, XCL, and PVP contributed substantially to intervention delivery and data collection. PYC, GTH, and AHYH drafted the original manuscript and analyzed the data. All authors provided critical feedback to several drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was part of a larger project supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) Academic Research Fund (AcRF) Tier 2 Fund [Ref no. MOE2016-T2-1-016].

Competing interests

The authors declare none.