Introduction

At the fifty-year anniversary of the adoption of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, it is time to reflect on the issues that have emerged and how they have been dealt with, exploring dimensions that need to be rectified in the future. Over the last three decades, a number of relevant publications have appeared, which have discussed diverse themes on World Heritage safeguarding and management. One of the most prominent and compelling of such themes is the politics of agencies dealing with cultural heritage and their shifting ideals and challenges. Among such agencies, most notably and consistently engaged are the World Heritage Committee (WHC), the United Nations Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and its partners, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM).

Apart from the politics of the international agencies, other subjects that have emerged include valuation, interpretation, and the presentation of heritage; looting, illicit trafficking, and the restitution of cultural property; cultural heritage site management; the conflict between conservation priorities and heritage tourism promotion; nationalism, globalization, and heritage; the global-local nexus; sustainable development; heritage ownership; human rights; and gender. Most often, these issues have been presented as case studies of individual properties.Footnote 1 The profusion of case studies makes it apparent that a half a century is a long enough time to reveal that UNESCO’s overall mission and the aim of the World Heritage Convention have faced enormous challenges influenced by world politics in general and politicization of World Heritage nomination ‘business’ in particular. UNESCO and the State Parties to the World Heritage Convention have paid selective attention to these serious issues emerged and focused on the obviously urgent and extreme cases such as natural disasters or violent attacks directed at cultural heritage sites.

Justifying their actions as “protection,” national authorities in developing countries frequently resort to draconian measures of control over heritage sites, imposing restrictions on local practices such as cultivation, hunting and gathering natural resources, access to the site, and new construction. Contrary to the notion of “protection,” however, excessive commoditization of both cultural and natural heritage is frequently encouraged by the same government authorities through the promotion of largely unregulated tourism development. This contradictory tendency is conspicuous in Southeast Asian countries, which tend to justify exploitation over protection in the name of alleviating poverty and/or in order to showcase national prestige. In such situations, measures that masquerade as site “protection” may conceal corrupt practices among business and political elites. In the process, confrontations between managing authorities and local communities have emerged at a number of sites. At times, such conflicts escalate to such a point where authorities may become culpable in the violation of human rights, the dislocation and involuntary removal of local inhabitants from their homelands, and sometimes the destruction of private property or even the infliction of physical and psychological damage on local stakeholders.

This article elucidates how, in the name of protecting outstanding universal values of world heritage, the very existence and practices of local communities may have been denied or severely curtailed by managing authorities at a number of Southeast Asian sites. While this tendency has been most notable in iconic ancient monumental heritage sites of national importance, the number and destruction of such violations at sites throughout the region is an indication that these problems are not isolated but endemic. The World Heritage sites that I discuss in this connection are three iconic sites, selected for their representative status – namely, Sukhothai in Thailand, Borobudur in Indonesia, and Angkor in Cambodia. All three sites have benefited as recipients of large-scale international assistance as the subject of UNESCO’s International Safeguarding Campaigns.Footnote 2 The sites of Sukhothai and Borobudur were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1991, and Angkor was inscribed in 1992.Footnote 3 Because of such high profiles and national significance, all three sites have experienced serious contestation between the managing authorities and local residential communities before and/or after their inscription.

In order to address this growing problem, this article also explores what measures may be adopted to rectify the precarious – and contentious – balance between the protection of heritage values and living practices of local inhabitants. Relatively well-managed World Heritage sites in this regard include the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province in Indonesia and the Historic City of Vigan, northern Luzon, in the Philippines. The Bali site consists of rice terraces, irrigation systems, sacred forests, temples, and villages. No local residents were forced out or had strict building regulations imposed on them. Tourism development has been managed by the local villages in collaboration with the district and provincial authorities.Footnote 4 In the case of Vigan, the original owners of the historic houses were actively involved in the conservation and tourism development of the buildings and the site, with the support of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the local government. Despite the requirement of further conservation and solving the issue of duplicating responsibilities among actors, Vigan has achieved a tremendous success for the country and for UNESCO, having been awarded Best Practice in World Heritage Management in 2012.Footnote 5 The fact that both sites are rather distant from major tourist destinations and are not iconic national monuments suggests that they have been able to avoid the abuse from national authorities with their national propaganda or excessive uncontrolled tourism development. The main reason for the relatively good management of these sites, however, seems to be that the local communities have taken the central roles in managing the cultural property in their sites, with the other actors, including the national authorities, assuming supporting roles.

Heritage protection, commoditization, and community exclusion from the tourist park

Prior to the promulgation of the World Heritage Convention, the conservation of cultural heritage had mostly been concerned with the protection and maintenance of physical structures and historical values.Footnote 6 The World Heritage Convention was the first international treaty on protecting, conserving, and presenting cultural and natural heritage that refers to the importance of involving local communities in this endeavor.Footnote 7 World Heritage inscription is generally seen to be an honor by the states containing the inscribed sites, which then tend to transform the sites concerned into archaeological, historical, or tourist parks. The legal and administrative tools for the conservation of historic monuments, using the monuments for reinforcing the state’s control over society and turning such historical sites into parks, are all based on European value systems and traditions, which have been imposed on archaeological sites in the former colonies.Footnote 8 After independence, these historical parks were taken, often unaltered, and nominated as World Heritage properties by the state parties.

In developing a heritage site into a park specifically targeting tourists and commoditization—whether before or after the World Heritage nomination—a degree of commodification of the heritage “product” for touristic consumption frequently occurs. However, in the process of commoditization, the authenticity of the sites is often impaired. Heritage parks designed as tourist consumption tend to be artificially beautified, and, in the case of religious monuments, visitors’ access is facilitated to what formerly may have been restricted sacred space. Through such strategies and actions taken at heritage sites, local inhabitants and relevant communities have often been dislocated, alienating the heritage from the local stewardship of the communities that either created or have subsequently come to care for these sites. Cultural links between the local people have been lost to a greater or lesser extent. Sukhothai,Footnote 9 Borobudur,Footnote 10 and AngkorFootnote 11 are examples where the local communities were partially or entirely removed from the sites before and/or after World Heritage inscription, ostensibly for reasons related to the conservation and safeguarding of the sites’ heritage values. The process of World Heritage nomination has often been interpreted or manipulated by the nominating states’ bureaucracies, which placed local values below national and international ones. In the process, these state bureaucracies have mainly focused on repurposing the sites for touristic consumption and recreation. In addition, national historic monuments with a new global brand, which has been created subsequent to their inscription on the World Heritage List, have often titillated the nationalistic pride of government officials who have justified their strict control of the local people’s activities in the name of protecting the national heritage “for the benefit of the world.”

The monument-centric protection and conservation approaches favored by national government bureaucracies, however, have increasingly become questioned in recent years. Since the 1980s, the notion of “sustainability,” especially as it is applied to the fields of environment and economic development, has played an increasingly larger role in international, national, and local debate and policy making.Footnote 12 This trend, no doubt, has influenced the policy making in culture and heritage as well. In 2015, “the role of culture and heritage in sustainable development was recognized by the United Nations (UN) in the 2030 Agenda and its seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).”Footnote 13 In the same year, the General Assembly of the States Parties to the World Heritage Convention adopted a Policy for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention at its 20th session in Paris.Footnote 14 Despite the emergence of such a paradigm shift in international concerns and policies, the Southeast Asian case studies show that the old rigid approaches to culture and heritage continue to linger, and local communities continue to be disenfranchised from their heritage.

Sukhothai, Thailand

In Thailand, the old conservation approach created historical parks out of historical archaeological sites. The management of these sites, including of Sukhothai, followed the normative template prevailing throughout most of the twentieth century, which was to “move all of the people away from the monument, erect a fence, and find another place for the people to live.”Footnote 15 It was an attempt by the government to transform the site as a symbol of “national” prestige and to control history while converting it into a landscape of “fantasy” to present and entertain both domestic and foreign visitors.Footnote 16

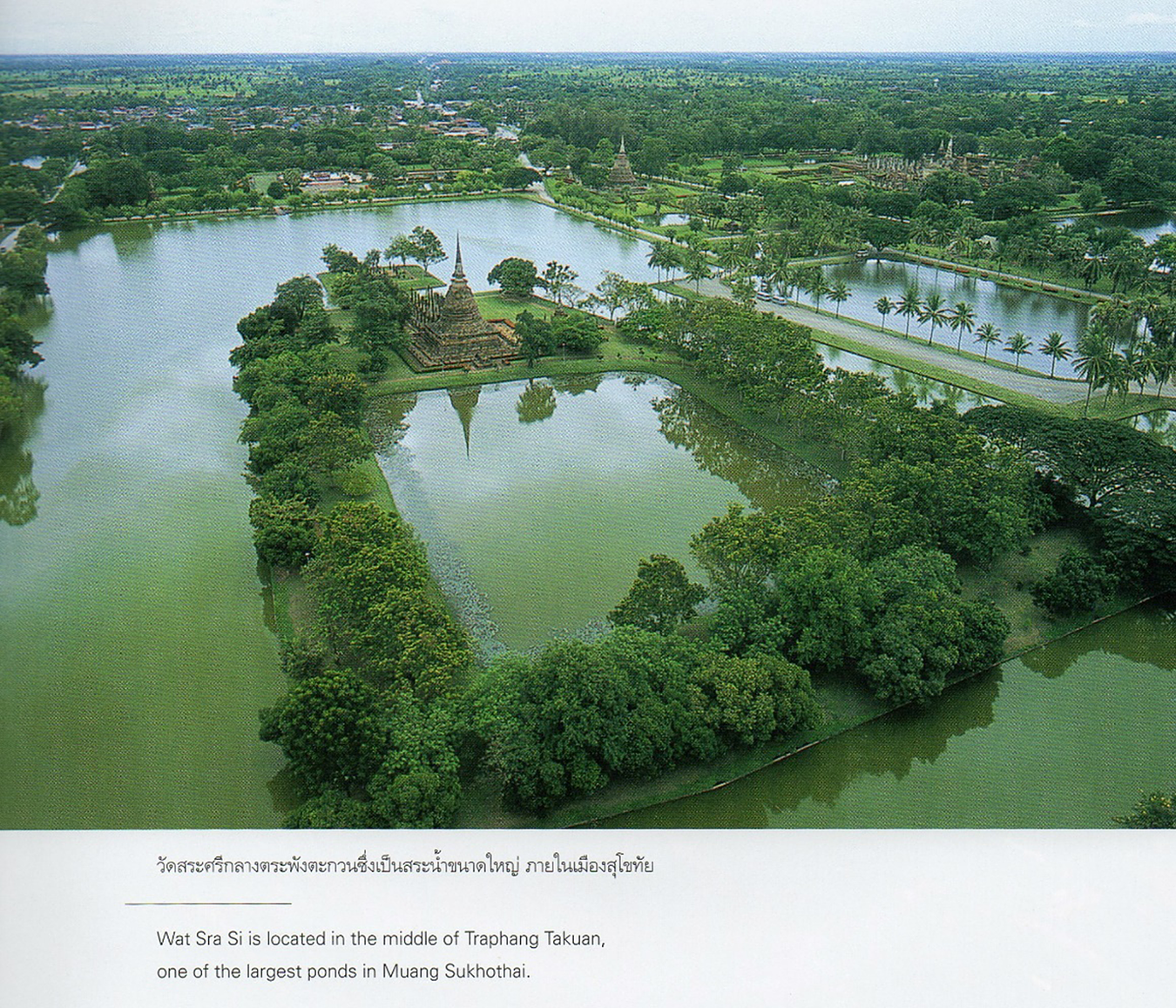

Sukhothai was the capital of the first Kingdom of Siam in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 17 Following the military coup that overthrew the absolute monarchy in 1932, the new government attempted to promote nationalism, upholding the national culture to inculcate a sense of collective selfhood.Footnote 18 In the process, individual sites began to be registered as national monuments.Footnote 19 An initial registration of the Sukhothai monuments was carried out in 1935 when 39 monumental complexes were officially classified as “protected monuments,” and the list was later extended to include other monuments. The first restoration of important monuments was carried out between 1953 and 1955.Footnote 20 Meanwhile, the foundation for transforming Sukhothai into a historical park began to take place with the realization by Thai officials that “the Sukhothai site deserved to be treated as a whole, and that the monuments should in future be presented not as isolated objects but in relation to each other and the countryside.”Footnote 21 Initially, the areas within the town walls were classified as “government-protected zones,” which were further extended in 1975 beyond the town ramparts, covering a total area of 70 square kilometers. This zone later came to form the Sukhothai Historical Park.Footnote 22

Figure 1. Aerial view of Sukhothai Historical Park and villages beyond (courtesy of The Aerial Views of Three Historical Cities. The Dawn of Thai Civilisation, 3rd ed [Bangkok: Muang Boran Publishing House, 2009], 13).

Figure 2. Arial view of Sukhothai Historical Park and the environs (courtesy of The Aerial Views of Three Historical Cities. The Dawn of Thai Civilisation, 3rd ed [Bangkok: Muang Boran Publishing House, 2009], 12).

The master plan of the Sukhothai Historical Park Development Project was drafted by a multidisciplinary team consisting of Thai specialists from universities and ministerial departments under the supervision of UNESCO experts.Footnote 23 The aim of the Sukhothai master plan was not only the restoration of ancient structures but also the revival of the historical environment of the city at the height of Sukhothai civilization. The plan was a ten-year project with six sub-plans: land use; archaeological excavation and restoration; landscape improvement; community development; settlement facilities and utilities; and tourist promotion. The plan was published in 1978.Footnote 24

Pierre Pichard, one of UNESCO’s experts for the project, writes: “The development plan for the project as a whole … aims at harmoniously combining the tourism development of the region with the new or traditional activities of the population remaining on the site.”Footnote 25 Concerning the local settlements, however, Vira Rojpojchanarat, the Thai architect of the Fine Arts Department, argues that “[t]his type of settlements not only destroyed the scenery but also proved difficult to provide public facilities.”Footnote 26 Nikom Musigakama, the then deputy director-general of the Fine Arts Department, had a dilemma that UNESCO, on the one hand, supported the technical guidelines outlined in the Venice Charter, while, on the other hand, encouraged the participation of local inhabitants in the conservation of monuments.Footnote 27 Nikom decided to implement the guidelines of the Venice Charter in their narrowest, most conservative interpretation. Consequently, he enforced the relocation of inhabitants living within the newly designated Sukhothai Historical Park.Footnote 28 In the end, “two hundred and sixty families living in areas which obstruct the views of ancient sites” were relocated outside the walls.Footnote 29

Nikom also instituted strict controls to stop the looting of archaeological artifacts from the site and to counter the illicit trade in Buddha images statues and other religious artifacts—trade that was (and is) strictly prohibited by Thai law. These actions, which were taken with the best of intentions to fulfill his responsibility as a government officer to protect Sukhothai as the site of the nation’s most significant heritage, nonetheless made him a target for threats on his life and caused him to have to hide for safety for a while.Footnote 30

Another controversy developed over a Buddha statue that was missing its head, which local devotees asked him to restore – with the original head if the original head was available or to replace it with another head if the original was lost.Footnote 31 With this restoration, the Buddha statue became “dead” and was without spiritual power.Footnote 32 This consideration became an important issue in the conservation (and restoration) of Sukhothai, prior to its inscription on the World Heritage List. Local villagers told the site conservators that they could not worship a headless statue even though the conservators explained that they could not produce an authentic reproduction head, from their imagination, based on no archaeological evidence. In the end, Nikom had to compromise with the local inhabitants by recreating a new head of the Buddha image at Wat Mahathat, the most important temple at Sukhothai, at the cost of the severe criticism he received from historians and archaeologists for this act of historical reconstruction.Footnote 33 In a symposium held in 1987 concerning the Sukhothai Historical Park, Nikom expressed his dilemma about the restoration of this large Buddha image, stating: “We tried to make the local and intellectual people satisfied and appreciative. But if we serve only the local people, the intellectual people may not appreciate.”Footnote 34 The important point here is that religious images in Thailand, along with other Buddhist countries in the region, are commonly regarded as objects of active restoration rather than conservation and not as “works of art,” as they are considered in Europe or by various heritage agencies.Footnote 35

Concerning tourism development, Maurizio Peleggi states that, in the late 1980s, the government’s official tourist promotion policy purposely emphasized the nations’ historic and archaeological heritage in an attempt to improve the image of the country that was notoriously reputed to be a sex tourism destination.Footnote 36 During the second half of the 1970s when Thailand was suffering from a serious economic recession, tourism was promoted as a way to provide a major source of foreign exchange earnings. The Tourist Authority of Thailand was established in 1979 to coincide with the launch of UNESCO’s International Safeguarding Campaign of Sukhothai. Subsequently, in the 1980s, Thailand saw a spectacular growth in international tourist arrivals – in a decade, the number of tourists jumped from 2 million per year to 5 million.Footnote 37

The areas of Sukhothai were recreated as a historic park designed intentionally to revive the (presumed) historical environment of the monuments’ urban structural remains as a commemorative tribute to the nation’s founding narrative, complete with the installation of a brand-new, bronze statue of King Ramkhamhaeng of Sukhothai, who was known mythically as a just ruler.Footnote 38 These efforts to redesign the “authentic” historic landscape of Sukhothai were undertaken in an attempt to meet visitors’ expectations that they would experience a “park”-like environment at Sukhothai.Footnote 39 The inauguration of the Sukhothai Historical Park in 1988 attracted some 434,000 international and local visitors, a marked increase in the number of tourists. The access roads into and within the site were paved, and a variety of transportation options were offered to visitors, including open tramcars, motorized coaches, private cars, and rented bicycles. Lush and beautified park-like landscapes were created using often non-indigenous plants and flowers.Footnote 40

Even at the time of the creation of the Sukhothai Historic Park, there were voices raised that were critical of the restorations carried out in order to beautify the archaeological ruins, including by Srisakara Vallibothama, a Thai academic, who decried these so-called restoration efforts as a “‘legally authorized’ process of destroying ancient and historic sites.”Footnote 41 Dhida Saraya, a doyen of the local history, who was initially involved with drafting of the Sukhothai Historic Park master plan, but later withdrew from the committee, observed that the “newly created environment stemming from historical fictions and myths … a park rich in fantastic structure and recreational sites reflecting no trace of shadow of the urban setting and planning of the past.”Footnote 42

In 1992, heritage sites throughout Thailand, including Sukhothai World Heritage site, was transformed into stage settings for the performance of a year-long series of reimagined folk, religious, and historical events. The most popular of all these events was a three-day Loy Krathong festival held amidst the ruins of Sukhothai. This festival allegedly dates back to the Sukhothai dynasty. On the night of the full moon in the lunar month that corresponds with December, farmers show their gratitude to water spirits for the year’s rice harvest by placing small floating offerings of flowers, candles, and incense in rivers and streams, symbolically shedding the year’s bad karma with the receding flood waters. This tradition was revived by Nikom, who had discovered a description of the festival in a historical document. Wishing to safeguard this cultural tradition and to publicize the presence of the Sukhothai Historical Park throughout the world, he reproduced the festival in the park. One archaeologist, who had voiced criticism of the inauthentic restoration of Sukhothai’s monuments, argued that the recreated Loy Krathong Festival was entirely unhistorical.Footnote 43 The organization of the Loy Krathong proved costly, and so to ameliorate the organizational cost incurred by the park’s management authority – and in the hopes of possibility deriving profit from it, the festival was “re-organized” as a Sukhothai Night. It consisted of a dinner show complete with music, staged entertainment, a beauty contest, and other attractions. The show has grown in popularity and now is a son et lumiere presentation of a glorified ahistorical version of the Sukhothai dynastic epic with re-created “traditional” dance and music performances, accompanied by a spectacle of fireworks and thousands of floating sky lanterns. Japanese academics have noted that the Sukhothai Night was organized to meet tourists’ demands more than to revive “authentic” Sukhothai culture.Footnote 44

Borobudur, Indonesia

Borobudur, a famous Buddhist temple in central Java, was built by the Sailendra dynasty, sometime between the eighth and the ninth centuries (Figure 3).Footnote 45 In the tenth century, when the center of power moved to East Java and the main religious faith of the local population changed from animism-Hindu-Buddhism to Islam, the temple fell out of daily use and public maintenance. Although the temple remained as a well-known site of pilgrimage by Buddhist devotees in south and central Asia, the protection and management of Borobudur had effectively been abandoned until its “rediscovery” by Dutch archaeologists at the end of the nineteenth century. A history of heritage conservation in Indonesia during the colonial period is well documented by Marieke Bloembergen and Martijn Eickhoff.Footnote 46 My concern in this discussion is over more recent official discourses and practices on the temple and cultural heritage, contrasted with other views and claims.

Figure 3. View of Borobudur (credit: Balai Konservasi Borobudur; Courtesy of Agency for Borobudur Conservation)

During the 1970s and 1980s, Indonesian academics and the general public engaged in a vigorous debate over the categorization of heritage, especially heritage containing pre-Islamic archaeological sites, arguing whether they should be classified as “living” or “dead.” During an Expert Meeting on the Protection of Cultural Properties in Asia, which took place in Tokyo, Japan, in 1972, R. Soekmono, who was the head of the Indonesian Archaeological Service, explained that “ancient monuments of more than 50 years old are considered as dead monuments which protection are under full custody of the government,” whereas “living heritage such as mosques, churches, temples, traditional private houses, public buildings and others are practically under full control of the community.”Footnote 47 Borobudur was therefore to be treated as a “dead” monument, not as “living” heritage.Footnote 48 This Indonesian official’s understanding of the conservation and management status of Borobudur was confirmed by Haryati Soebadio, director-general of culture. He stated that, out of the two categories of heritage, Borobudur would be classified in the category of “dead monuments” built during the Old Javanese Kingdoms, insisting that Borobudur was no longer used for Buddhist ceremonies.Footnote 49

Buddhism in the Dutch Indies, however, had been revived in the first years of the twentieth century through the efforts of a Sinhalese monk by the name of Nāranda Thera. Waisek, the celebration of the anniversary of the Buddha’s enlightenment and death, was revived at the initiative of the Dutch Theosophical Society, which consists of a European and Javanese elite membership. The first modern celebration of Waisek held at Borobudur took place in 1929. With some interruptions, this annual ritual has continued to be held on the site more or less on a regular basis.Footnote 50

Representatives of the Buddhist minorities voiced their worries about the desacralization of Borobudur temple compounds as a place for religious prayers and healing caused by the site’s commercialization as a tourist destination. During the dismantling of Borobudur for restoration from 1973 to 1983, the government disallowed the minorities to organize Waisek at Borobudur. The ceremony was organized instead at another Buddhist temple of Mendut nearby, which was built in the ninth century.Footnote 51 The majority of Javanese and Indonesians are now Muslims, so for them Hindu or Buddhist monuments are regarded as “ancient and dead cultural heritage,” not as “living heritage.” It is convenient for the government to maintain the value messaging of Borobudur in a static way that is devoid of religious, political, or other cultural connotations. This management policy facilitates the control of potential religious revivalisms, which might enflame regional political upheavals such as those that took place after independence and again during the 1980s. Nevertheless, and in spite of these political reservations on the part of the government, due to popular demand from 1984 onwards, Waisek became an annual event and is now celebrated as a national holiday.Footnote 52 At the same time, a Muslim prayer hall was built next to Borobudur’s entrance gate in 1984, suggesting the government’s recognition of the “living” religious dimension of the temple.Footnote 53

As for the issue of the restoration of Borobudur vis-à-vis local communities, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) began surveys for a master plan of Borobudur and Prambanan Archaeological Parks in 1973, in response to UNESCO’s appeal to the international community to come to the aid of the Indonesian government to safeguard these monuments.Footnote 54 Heather Black and Geoffrey Wall have criticized the fact that JICA’s draft master plan was made without the residents’ knowledge, even though their land was to be confiscated to create the parks.Footnote 55 According to Masanori Nagaoka, however, JICA’s plan stressed that “collective decisions made by the Indonesian authorities and community be given priority consideration to ensure the preservation of Borobudur and surrounding areas.”Footnote 56 Japanese experts involved in formulating the plan also recognized the similarity between Japanese and Javanese concepts of “sacred landscapes encompassing natural features.”Footnote 57 This was decades before UNESCO’s adoption of cultural landscapes as one of the nomination criteria. Merging the criteria of cultural and natural heritage into a single comprehensive system for the valuation of nominations to the World Heritage List was only adopted by the WHC in 2005.Footnote 58

When Indonesian authorities prepared a dossier for the World Heritage nomination in the late 1980s, they were “required to reconceptualize the cultural and natural aspects of the landscape as separate.”Footnote 59 Borobudur was then presented not as a cultural landscape but, rather, as a historical monument to the WHC in 1991; adopting European ideas and traditions of heritage was the only value presented as universally significant and therefore to be protected as a priority. The primacy of protecting the material values of the monument became official Indonesian government policy.Footnote 60 As a result, the lands belonging to the inhabitants were expropriated to create the national archaeological park as a taman wisata (tourist park) in Borobudur. This land expropriation was minimally compensated, and the landowners were offered new land for settlement and agriculture outside but near the park.Footnote 61 The authorities justified the exclusion of communities from heritage management responsibilities that focused on monument preservation based on the 1931 Monuments Act, reflecting the Netherlands’ colonial conservation policy.Footnote 62 The European conservation ethic of preserving ancient buildings – in particular, those found in their colonies – can be succinctly described as a policy intended to “retain their historical character and their value as material traces of the past, which was essential for the study of human achievement in the past.”Footnote 63 Within this paradigm, there was no room for a “living” dimension of heritage, let alone a holistic concept of a cultural landscape.

In 1981, local villagers complained about the government’s decision on their relocation to the head of the Regional Parliament of Central Java, and this complaint was simply ignored and their relocation began.Footnote 64 The inhabitants of Kenayan and Ngaran, two villages closest to the temple (less than 500 meters), however, were unwilling to move. In 1983, about 100 families living around the temple protested against the plans for a national park. Eighty-nine families in these villages were still living within the boundaries of the new park, but they were made to leave by 1984 with combined tactics of persuasion and intimidation used by the authorities of the New Order regime.Footnote 65 The access of the local villagers to the temple site became more difficult after the terrorist bombing of Borobudur in 1985, which damaged nine of its 72 stupas on the upper terrace.Footnote 66 The attack was apparently orchestrated by Indonesian Islamic extremists in a coordinated series of bombings from 1984 to 1985.Footnote 67 Borobudur was targeted for the bombing because “[t]he militants perceived the government’s renovations of the structure (largely for purposes of tourism) as emblematic of the state’s refusal to embrace Islamic law.”Footnote 68

After the event, security measures were tightened so that the temple compounds were fenced in with barbed wire.Footnote 69 Because of the fences, the local residents felt that their ties with the monument and the land around it, which were already estranged, were further impaired. Even though the local inhabitants who live in the vicinity of Borobudur are officially Muslim, they consider this ancient Buddhist monument to be sacred and believe that it has a function of protecting their communities. At the time of marriage or for specific (healing) purposes, local inhabitants make offerings at the Waringin tree near the main stupa of Borobudur.Footnote 70 The persistence of ancient local traditions is commonplace in Javanese spiritual practice. Beliefs are multilayered, with mountain worship being important as the abode of ancestors. These ancient practices were overlain with the Hindu-Buddhist cosmology of Mount Meru, prior to the adoption of Islam, which, in turn, became blended with elements of these earlier beliefs.Footnote 71 Nevertheless, drawing up modern protection regulations for the site, the government disregarded the spiritual connection of the local inhabitants to the temple and even went so far as to restrict access to the temple by members of the local community, reserving this privilege for tourists only. This was due to the fact that the government delegated the management of tourism facilities to state-owned firm PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur and Prambanan.Footnote 72 Such newly imposed restrictions made the locals feel disconnected from their homeland, which was symbolized by the temple(s). The relationship between the former residents and the government officials grew increasingly tense and sometimes violent because of mutual mistrust and hostilities.Footnote 73

At Borobudur, local residents formerly used their homes as shop fronts to offer visitors goods and services, but, after their relocation, they had to rent identical kiosks inside the park at the periphery of the parking lot. This rearrangement of business reduced their economic opportunities.Footnote 74 Michael Hitchcock and I Nyoman Darma Putra also note that “local villagers around Borobudur and Prambanan are routinely ignored in plans to turn both monuments into major tourism destinations.”Footnote 75 Christopher Silver elaborates one such plan at Borobudur in which the Central Java provincial government proposed to construct an art market known as “Java World” in 2003 when local contestations flared up again.Footnote 76 The official reason for this plan was to help “conserve the temple site by restricting vendors to a designated space separate from the monument” and thereby to facilitate tourists’ unimpeded access to the site.Footnote 77 The government emphasized that the project was “meant for public welfare.” Local artists and venders “saw the Java World project as a direct threat to the hawkers who would be removed from the site and thus denied their customary livelihood.”Footnote 78 Critics also contended that it would generate revenue for the local and central governments at the expense of jobs for hundreds of poor hawkers.Footnote 79

The consequences of Borobudur’s inscription on the World Heritage List came to have a repercussion later in Bali when the central government, together with some Balinese intellectuals and conservators, proposed that the supreme Bali-Hindu temple complex of Pura Besakih be nominated as a World Heritage site. This proposal faced stiff local resistance in the 1990s. Balinese opponents “did not want Besakih to be treated like Borobudur where ritual activities had been banned.”Footnote 80 This reaction indicates a widespread misunderstanding of World Heritage inscription and a fear that inscription provides an excuse for extending the central government’s control over an important site of continuing traditional beliefs and living cultural practices. A reinforcing factor that influenced the rejection of the proposal for the nomination of Besakih as World Heritage was the understanding that it is the national government, not provincial or local authorities, that is mandated by the 1972 World Heritage Convention as well as by Indonesian law. For Balinese Hindus, it would have been difficult to “to hand over the protection and conservation of their temples to institutions that were non-Hindu (i.e. the institutions of the Indonesian state).”Footnote 81 Consequently, three attempts to propose Pura Besakih for a World Heritage inscription – the latest dating to 2001 – have all failed to obtain local support and so have been abandoned.Footnote 82

Angkor, Cambodia

Angkor, the capital city of the Khmer Kingdom, flourished from the ninth century to the mid-fifteenth century. At its height, it controlled a large portion of the mainland of Southeast Asia. Repeated attacks by Ayutthaya have traditionally been credited as one of the reasons for the fall of the kingdom, when the ruling classes fled eastward, abandoning Angkor. In 1794, Siam annexed the Cambodian provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap, together with the site of Angkor. Although the site continued to be inhabited by a small population and function as a pilgrimage destination, the monuments and their supporting infrastructure were not maintained or repaired except for limited restoration and maintenance conducted from the sixteenth into the eighteenth centuries. After a long period of neglected maintenance, the Angkor monuments were “rediscovered” by Europeans and others, but most notably by the French in the nineteenth century.Footnote 83 Angkor was then reconfigured as an archaeological park for research and tourism by the French. During this process, people who had been living, presumably for generations, inside of Angkor Thom (meaning “capital city”) and Angkor Wat (meaning “city temple”) (Figure 4) were dislocated to live outside the moats of both the ancient city and the city temple.Footnote 84

Figure 4. Angkor Wat (courtesy of Masako Marui).

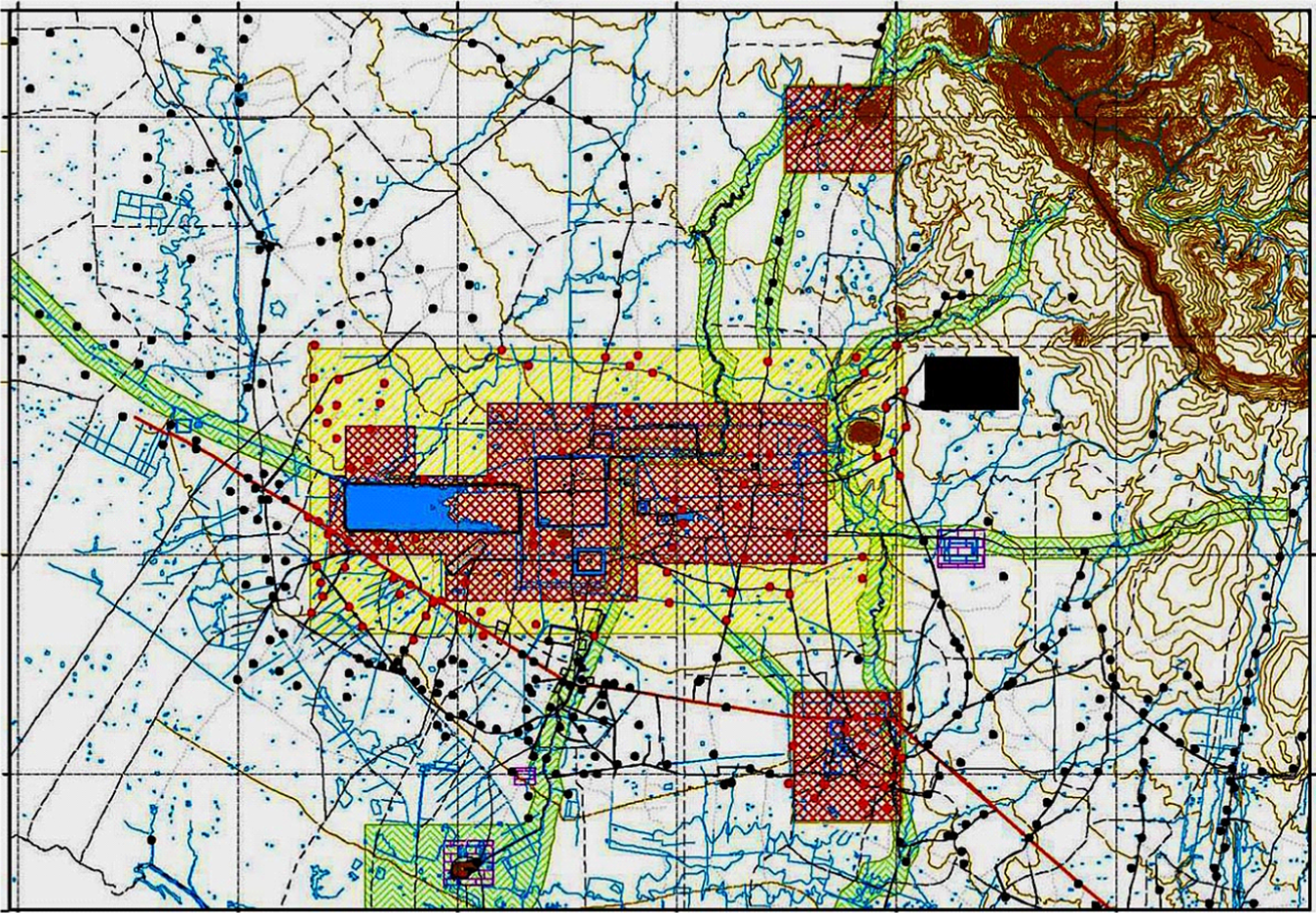

The Angkor Park (Parc d’Angkor), otherwise called Angkor Archaeological Park, officially opened in 1925 during the colonial period. Larger areas that overlapped with Angkor Park were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1992. These areas consist of three monument groups with a large “relic cultural landscape” of thousands of smaller archaeological sites – that is, Banteay Srey in the northeast, Angkor in the center, and Roluos in the southeast (Figure 5).Footnote 85

Figure 5. Map of Angkor zones (Zone 1: Monumental Sites in red; Zone 2: Protected Archaeological Reserve (Buffer Zone) in yellow; Zone 3: Protected Cultural Landscapes in green; Zone 4: Sites of Archaeological, Anthropological or Historic Interest in blue; Zone 5: Socio-economic and Cultural Development Zone of the Siem Reap Region (whole of Siem Reap province). Black circles indicate villages; the black rectangle near the buffer zone is Run Ta Ek (courtesy of the APSARA Authority).

In 1992, Angkor was simultaneously inscribed on the World Heritage in Danger List, waiving some conditions required under the Operational Guidelines.Footnote 86 This arrangement was made due to Cambodia’s unique situation under the temporary UN administration and the urgent requirement to address problems of protection and conservation at the site, quickly and effectively.Footnote 87 In 1993, the International Coordinating Committee for the Safeguarding and Development of the Historic Site of Angkor (ICC) was established at the Tokyo conference, through which all issues concerning research, restoration, conservation, and development projects and proposals must go. At the ICC at that time, France and Japan were the co-chairs, and UNESCO was the standing secretariat. In 1994, the Authority for the Protection of the Site and Management of the Region of Angkor (APSARA) was established to be responsible for the protection, management, and development of the site.Footnote 88

Initially, a lack of manpower and funds, and rivalries with other ministries and the Siem Reap provincial authority, hindered the effective functioning of APSARA.Footnote 89 Meanwhile, beginning in 1994, a special unit of the French police at the request of UNESCO and in cooperation with the Ministry of the Interior, was deployed to set up and train a unit of “cultural heritage police,” which resulted in the formal establishment of an Angkor police force in 1997. The priority duties of this new Angkor police force were to stem the flow of illicit trafficking in antiquities and included consciousness-raising programs directed at the local population and the reinforcement of local communication networks in order to ensure the protection of the site’s monuments and archaeological artifacts.Footnote 90 The initial operations that the Angkor heritage police carried out were intended to establish control over the heritage space. However, actions to accomplish such efforts were implemented without consultation, coordination, or cooperation with APSARA – hence, the tactics employed were sometimes questionable, and the results only partially effective. In particular, the tactics of the heritage police, while intended to stop illegal smugglers, also negatively impacted innocent members of the local community. The “illegal” (that is, unauthorized by any legal authority) activities of the heritage police included collecting “a fee” or voluntary donation from those who passed through the gates of Angkor Thom. The victims caught in the net included local villagers’ riding bicycles or motorbikes to go to sell their products at markets in Siem Reap, hawkers, shopkeepers, and stall owners working at tourist concessions near the major monuments. It was just the beginning of an increasingly systematic (and, from the local villagers’ perspective, draconian) police control of the formally freely accessible Angkor space that villagers had relied on for traditional agroforestry and other subsistence activities.

Drastic measures were taken by the heritage police culminating in 2000 when a ban was imposed on local villagers living within Zones 1 and 2, which prohibited them from conducting traditional agroforestry activities as well as cattle herding within Angkor Thom, the compounds of other historic monuments, and the exterior bank of the Angkor Wat moat (Figure 5). Villagers were deprived access to the rice fields in the many ponds and some parts of the Angkor Thom moats. Access to forest resources (to collect tree resin, for instance, which is needed to burn for domestic lighting and for sale as boat caulking to fishermen in nearby Tonle Sap Lake; honey and other food resources; and lumber and thatch-building materials) was also restricted. Only those who could bribe the heritage police were allowed to continue some of these traditional activities. If anyone refused to comply, the heritage police confiscated the land to cultivate for and by themselves. Although the villagers considered these lands and trees to be “their” property by tradition and convention, no compensation was offered to them when they were deprived of these economic resources by the heritage police authority. Not surprisingly, local villagers came to associate heritage “protection” with the expropriation of, and restricted access to, their traditional lands and resources, which caused a downward slide into increased economic poverty among a group of subsistence farmers who already were living in marginal circumstances.Footnote 91

It needs to be noted that the ban on traditional land use imposed by the heritage police contradicted articles stipulated in the so-called “zoning law,” which constituted part of the Angkor World Heritage Management Plan, promulgated by the ICC and endorsed by the WHC. In Article 16 concerning the management of natural resources, there is a clause on land management within Zone 1, which is specifically intended to “(m)aintain traditional land use in the form of rice paddies and pasture” (Figure 5).Footnote 92 Still, some articles of the zoning laws contradicted one another, which was exploited by the heritage police to their advantage, ostensively on behalf of APSARA, but in effect to control the productive potential of the land to the benefit of individual members of the new authorities. In 2000, the heritage police chief told local villagers: “Do not think that because you have been living in the Angkor zone that Angkor belongs to you? It does not!”Footnote 93 Because of these sudden drastic measures taken vis-à-vis local villagers, their relationship with the heritage police grew tense.Footnote 94

At the Paris conference in November 2003, commemorating the tenth anniversary of the ICC, a major policy shift was announced from urgent safeguarding to sustainable development. The 10-year action plan for urgent safeguarding was deemed to have been, for the most part, successfully accomplished. Subsequently, in 2004, Angkor was removed from the World Heritage in Danger List.Footnote 95 One result of this change of management strategy was that APSARA quickly assumed the primary position of authority, with Sok An, the first vice-prime minister of Cambodia, appointed as APSARA chairman and departments and manpower rapidly augmented, and the operational scope of APSARA extended. The ban of 2001 to restrict the activities of local residents was reissued with more details of the prohibitions and administrative measures for their enforcement as the Order of the Royal Government no. 02/BB in 2004.Footnote 96 The heritage police were incorporated into APSARA’s newly created Mix Intervention Unit (MIU) with other police forces, which was renamed later in 2008 as the Department of Public Order and Co-operation (DPOC). The structural change in the police force, however, has turned out to be more intimidating, and corruption has been institutionalized to the further detriment of the local communities.Footnote 97

With expanded bureaucracy and staff, including staff assigned to site surveillance, APSARA began to strictly control the new construction of houses, and any demolition was entrusted to the DPOC. The justification for this policy was based on APSARA’s understanding of its mission and mandate “to preserve the cultural landscape and authenticity of this marvellous site (Angkor).”Footnote 98 Behind the issuance of this policy lay the need to accommodate the rapid increase of people to the World Heritage site, which was mainly caused through the increase of migrants from other provinces who illegally purchased land in Zones 1 and 2 in order to live in Angkor villages, many for profit making through tourism. In an attempt to control this “illegal” expansion of structures within the protected zones of Angkor, only the presumptive “original owner” of the house was allowed to extend or reconstruct his or her house, not including his or her children or anyone else. APSARA, knowing that it was unable to forcibly relocate “genuine” villagers, encouraged young couples to live in Run Ta Ek, the so-called “eco-village,” complete with anachronistic windmills, outside the World Heritage site boundaries (see Figure 5). This alternative residential site turned out to be unpopular with residents because the site was so far from Angkor that it was difficult for them to find jobs or to visit family members upon whom they were dependent for support.Footnote 99

For the local inhabitants, the heritage space has long been their homeland. In particular, Angkor Wat has long served as a culture center where males have been ordained and/or studied; religious ceremonies and New Year games performed; guarding spirits and the Buddha worshipped; monks consulted; and visitors greeted and interacted with. A Buddhist monk of Angkor Wat, whose village was just outside the moat, said: “I have lived all my life seeing Angkor Wat. I cannot imagine living in a place without it.”Footnote 100 In formulating just, equitable, and long-term sustainable development practices to manage the Angkor World Heritage Centre, it seems important to take into consideration the strong sense of belonging that the locals feel toward their heritage, which at the same time comprises their most sacred space and provides them with a sense of protection.Footnote 101

Based on the regulations on construction stipulated in the Cambodian government order of 2004,Footnote 102 APSARA’s monitoring unit members on motorbikes are deployed daily to survey the situation in every village in Zones 1 and 2 of the World Heritage property. The monitoring unit takes photos of houses, of which reconstruction has been requested as well as investigates whether villagers are preparing or have begun to construct houses, animal pens, toilets, or any other structures without the required permits from APSARA. If reported to the MIU-DPOC as an “illegal” construction lacking a permit from APSARA or not in conformity with the building codes set by APSARA, the buildings under construction or completed must be taken down and removed by the owners themselves, or they will be forcibly demolished by the armed units of MIU-DPOC who are accompanied by APSARA staff members. In the course of forced demolition, construction materials and tools, and valuables such as money, gold, and mobile phones often “disappear.” Most victims of enforced demolitions were the poor, widows, the handicapped, and/or AIDS patients, some of whom were threatened with violence and/or gun shots on the occasion of demolition (Figure 6). Foreigners, APSARSA employees (mostly laborers or guards), villagers who can afford to bribe the demolition team, or those who have connections to high-ranking officials, however, can avoid demolition. APSARA also encouraged villagers to inform it about “illegal” constructions attempted by fellow villagers. In one village, people talked about APSARA “spies” among fellow villagers, impairing the unity of the community.Footnote 103

Figure 6. A shack demolished by the DPOC in 2010 (courtesy of the author).

Tourism development and the hardship imposed on the local communities have gone hand in hand. In the course of reconstructing “Angkorean” landscapes for conservation and tourism, APSARA has created canals to pump up water into a stagnant artificial reservoir, Jayatataka Baray and the dried-up pond of the Neak Poen temple at its center (Figure 7). For the creation of the canals, some rice fields were sacrificed for insufficient compensation, in addition to the flooding that damaged rice in other paddies, for which no apologies or compensation was made by APSARA. Some seniors from the local villages who took care of the religious statues voluntarily at the Bayon temple, which is located at the center of Angkor Thom, were removed based on the allegation of making profits from tips given to them by tourists in the sacred place. However, large “buffed” dinner parties were occasionally organized for tourists by the hotels of Siem Reap with traditional dances and theaters shown in the compound of this temple (Figure 8). The same costumed dancers and actors began to appear in Angkor Thom, Angkor Wat, and other grand temples popular with tourists. They were photographic models for tourists to pay for the photographs (Figure 9). Double standards of rules and regulations were applied by the authorities, whereby local residents were those who lost out.Footnote 104

Figure 7. Water-filled Jayatataka Baray with a new wooden passage to the Neak Poen temple (courtesy of the author).

Figure 8. Bayon Temple with a dinner show in preparation (courtesy of the author).

Figure 9. Photographic moment with models in dance costumes at Angkor Wat (courtesy of the author).

The nocturnal son et lumière show that took place for General Charles de Gaulle in front of Angkor Wat in 1966 was also recontextualized and reintroduced in 2008 as the Angkor Wat Lighting Project with night tours.Footnote 105 This project was produced by APSARA, together with the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts and the Sou Ching company, in order to prolong the stay of tourists in the area, which at the time was suffering from a 20 percent drop in visitors.Footnote 106 The nightly production was massive, with the entire temple interior lit up and wired throughout for sound. It also involved more than 150 performers, 45 lighting technicians and engineers, and 50 support staff. A traditional dance show was held on the stage with light gantries specifically set up for the venue. At a dining area, an up-market Khmer dinner was provided for guests.Footnote 107 Controversies soon developed when the Sou Ching company began the light installation project. In the course of installing light bulbs on the stones of Angkor Wat, the temple allegedly sustained damage. The local population was also lamenting over the excessive commoditization of Angkor Wat and did not wish the temple to be (ab)used in this way. The locals, in general, consider Angkor Wat to be a sacred place and not suitable for entertainment.Footnote 108

Both Sou Ching and the government stated that the claim was false and that the company used existing holes only. Jamie Rossiter, the former director of marketing for Sou Ching, reportedly stated: “We have our mandate from the government. It was APSARA, UNESCO and the government together which said we need to use the temple more, we need visitors to be visiting more and enjoying it more and there is more we can be doing with these temples.Footnote 109 Like this claim, the name of UNESCO is often used by the authorities and their related bodies when some projects become criticized by the people, including the aforementioned demolition of new houses. The consequences of these controversies were that the government filed a suit against Moeung Sonn, president of the Khmer Civilisation Foundation, for his claims that a hole had been drilled deep into the temple’s walls. Having been charged with spreading false information and inciting the public in connection to his claims, he fled to France to avoid arrest.Footnote 110 The project abruptly halted.

Conclusion and exploration of possible approaches for solution

In the 50 years since the ratification of the World Heritage Convention, the world has observed how UNESCO’s ambitious ideals to protect heritage sites of “outstanding universal value” over the very long term and to overcome the limitations of national policy interests have been variously translated and manipulated by the state parties and their management partners. Out of numerous issues emerging from the implementation of the convention, I have discussed some common problems shared by the most iconic World Heritage sites in Southeast Asia. The selected sites for examination in this article – Sukhothai in Thailand, Borobudur in Indonesia, and Angkor in Cambodia – are sites of monumental religious heritage and are set within urban cultural landscapes consisting of numerous archaeological remains. In spite of having been abandoned as urban centers, these sites continue to have religious and cultural significance for local communities surrounding the sites. In recognition of their asset potential, the governments of the region have turned these sites into parks, primarily for the purpose of “protection” and attracting tourists.

As a consequence, the sites have attracted investment, sourced from both the government and the private sector, in conservation, restoration, and infrastructure development intended mainly to commoditize the sites’ historical assets through the facilitation of recreational visitation. Converting heritage sites into historic parks for tourism purposes is a strategy borrowed from European models applied in their former colonies and emulated widely by nations in the post-independence period. In the process of creating these new national historical parks, local inhabitants were often involuntarily relocated to outside the core archaeological zones, making it problematic for them to continue to make a living in their traditional manner, as access to land within the new parks was severely restricted, if not prohibited outright. The concept of “living heritage” has been interpreted by managing authorities in convenient ways. In Indonesia, where Muslims are the majority today, cultural heritage was officially divided as “living” (still maintaining religious or cultural traditions) or “dead” (the religion and customs belonging only to the past) based on contemporary religious and political concerns. Borobudur was designated as “dead” heritage by the Indonesian government, even though the temple actually continues to be worshipped by a minority of Indonesian Buddhists who organize an annual rite and even by local Muslim residents who regard the temple as sacred and protecting their communities. Borobudur also has long been a pilgrim site among Buddhists from other countries, even though some may visit there as tourists today. On the other hand, the majority of the population in Thailand and Cambodia are Buddhists, and historical monuments and religious images in Sukhothai and Angkor have continued to be worshipped, and they are therefore categorized as “living” heritage. How to conceive and deal with the “living” aspect of heritage is however arbitrary, but the authorities tend to restrict traditional local use of the heritage space often to their advantage, while converting it to the landscape of fantasy where monuments are used as stages for lively historical entertainment for tourists.

The World Heritage nomination and inscription process was used by the state parties of these three case studies examined here as a means to control the people and their activities, justified by recourse to the “greater cause” of national prestige. The name of UNESCO has often been ab(used) to silence people or redirect their anger toward the abstract and untouchable “international community.” In the process of their transformation into tourist parks, each of these sites has been the setting for tacit or observed confrontations between local communities and the authorities managing the World Heritage sites to differing degrees because of the dislocation and exclusion of local communities from their traditional heritage spaces. In each of them, little prior consultation was provided by the authorities to the subject people before delivering orders to restrict traditional practices, displace, if not distance, them from their ancestral homes, and relocate them elsewhere. In the most extreme case studied – that of Angkor – confrontation between the local communities and the authorities became quite intense because of ambiguous rules and regulations, combined with arbitrary and unequal enforcement by the managing authority, APSARA, which was exacerbated by corrupt practices of some officials. Poor and vulnerable individuals, such as landmine victims or widows, have been particularly susceptible to victimization by the site management authorities, even to the point that can be considered a violation of their basic human rights. In each of these case studies, traditional communally managed heritage space has been converted to a land of touristic recreation and entertainment at the expense of the authenticity and integrity of the historical sites.

In the past 50 years, it appears that heritage safeguarding practices have deviated far from the ideals of the World Heritage Convention, in the pursuit of the exploitation of the perceived economic potential of heritage sites. Better, fairer, and more sustainable ways of managing World Heritage sites need to be devised in a way that fully respects the human rights of impacted communities. Key UN international heritage agencies – that is, UNESCO, ICOMOS, and ICCROM – have made clear that the long-term sustainability of a community’s heritage is the primary goal to be pursued, and all are in agreement in stressing the importance of increased local participation in heritage site management and socio-economic development.Footnote 111 It is now crucial that such new directions and approaches penetrate into the mind and work of policy makers, heritage practitioners, and community members alike. Open discussions, workshops, and appropriate skills training for all stakeholders concerned in the management and utilization of heritage sites should be organized whenever possible and must be required. As for the site monitoring and evaluation of management strategies in place at sites, it may be beneficial to envision a role for an external third party like NGOs, not the government-appointed agency, in order that an unbiased and realistic appraisal be reported to the WHC. The basic question confronting all heritage managers is: what kind of knowledge and values surrounding our and their “heritage” do we wish to pass on for whom, and how will we do this? Our knowledge and appreciation of both cultural and natural heritage will surely be enhanced with the addition of local knowledge, augmenting the academic knowledge we gain through historical studies and professional practice.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following individuals who assisted me in a variety of ways: Akiko Tashiro of Hokkaido University; Masako Marui of Sophia University; Richard Engelhardt, former UNESCO Regional Advisor for Culture in Asia and the Pacific; Hatthaya Siriphatthanakun of SEAMEO Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts; Rizky Fardhyan of the UNESCO Office in Jakarta; Agency for Borobudur Conservation; blind referees; Lynn Meskell, one of the editors of this special issue of International Journal of Cultural Property; Sarah Mady, editorial assistant of the journal, and Stacy Belden, copyeditor of the journal. Lastly, but not least, my appreciation is dedicated to all the people that I have met and interviewed during my research and to my various assistants – in particular, Ang Chong.