The Mediterranean diet (MD) is derived from the traditional dietary habits of people living around the Mediterranean basin(Reference Iaccarino Idelson, Scalfi and Valerio1). because it is linked to major health and nutrition benefits, a substantial body of scientific evidence has demonstrated the importance of the MD in preventing a number of chronic non-communicable diseases and maintaining good health over the entire lifespan(Reference Martinez-Gonzalez and Bes-Rastrollo2).

Despite the well-known benefits of the MD, current lifestyle changes characterised by a high consumption of processed food, sugar, soda and meat products (i.e. Western dietary pattern) have become a growing public health concern and are a major contributory factor to the global epidemic of obesity(Reference Monteiro, Moubarac and Cannon3,Reference Tur, Romaguera and Pons4) . Another factor related to obesity and associated health conditions is the increase in sedentary behaviours, such as increasing time spent on watching television, playing video games and using the Internet and reductions in physical activity (PA)(Reference Andersen, Crespo and Bartlett5) and physical fitness levels(Reference Tomkinson, Lang and Tremblay6). In this regard, evidence suggests that food habits of youth are strongly influenced by several factors such as healthy lifestyles(Reference Iaccarino Idelson, Scalfi and Valerio1) and physical fitness(Reference Thivel, Aucouturier and Isacco7,Reference Cuenca-García, Ruiz and Ortega8) in a complex interactive manner.

Childhood and adolescence are critical periods in life for the adoption of lifestyle habits that are likely to persist into adulthood. Because many chronic diseases that manifest in adulthood stem from childhood(Reference Pearson and Biddle9), it is important to establish healthy habits early in life. Also, healthy behaviours do not act in isolation, and the effects of multiple healthy lifestyle behaviours may be greater than the sum of their individual impacts(Reference Rosi, Giopp and Milioli10). For this reason, the relationship between adherence to the MD, PA, sedentary behaviours and different parameters of physical fitness has been analysed in several studies, but inconsistent results have been reported, and a meta-analytic understanding of how the MD adherence contributes to healthy habits and physical fitness in youth remains unknown. Thus, the aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was to synthesise the evidence regarding these relationships and to quantify their associations in children and adolescents.

Methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and was registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (registration number: INPLASY202040032). The entire process from literature selection to data extraction was performed independently by two researchers (A. G.-H. and Y. E.). Any disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third researcher (R. R.-V.).

Selection criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies needed to meet the following criteria (using PICOS criteria): (i) participants: generally healthy population aged 3 up to 18 years (mean age); (ii) exposure: MD measured using the KIDMED test (Mediterranean Diet Quality Index); (iii) comparisons: exposed v. non-exposed youths; (iv) outcomes: PA, sedentary behaviour and physical fitness and (v) study design: cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies. The first and second reviewer (A. G.-H. and Y. E.) assessed the full-text articles for eligibility. If a single study assessed different sedentary behaviours (e.g. television watching, computer use, sitting time), all effect sizes were extracted.

Search strategy

Two investigators (A. G.-H. and Y. E.) systematically searched MEDLINE, Embase and SPORTDiscus electronic databases for articles, from inception to March 2020. We used variations of the terms MD (e.g. Mediterranean, diet, adherence), children and adolescents (e.g. child, children, adolescent, adolescents, youth), PA (e.g. active, exercise, physical inactivity), sedentary behaviour (e.g. sitting time, screen time, screen media, electronic media, Internet use, computer use, mobile phone use, television watching, video game) and physical fitness (e.g. cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), aerobic fitness, muscular fitness, muscular strength) (online Supplementary material 1). Searching was restricted to published articles in the English and Spanish languages.

Data collection process and data items

The extracted data from the articles meeting the selection criteria included the following information: (i) study characteristics (the first author’s name, publication year, enrolment year, study location, sample size, study design); (ii) participants’ information (sex and age); (iii) measurement details (method of MD, PA, sedentary behaviours and physical fitness assessments) and (iv) analysis and study results (adjusted variables, outcome of interest and main results). We requested from the study authors any effect sizes that were missing from the original published papers.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies was used to evaluate the risk of bias(11). The checklist comprised fourteen items for longitudinal research, of which only eleven could be applied to cross-sectional studies. Each item of methodological quality was classified as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘not reported’.

Summary measures

We chose the correlation coefficient (r) as the main effect size for the present meta-analysis. Effect sizes reported by studies were standardised regression coefficients (β), unstandardised regression coefficients (beta), standardised mean differences (Cohen’s d) and OR. We converted all of these estimates to correlations according to their corresponding formulas(Reference Nieminen, Lehtiniemi and Vähäkangas12–Reference Bring14). If adjusted and unadjusted effect sizes were provided, we selected adjusted. Correlation coefficients were entered along with the corresponding standard errors or sample size, and the software was set to produce pooled r values with 95 % CI using a random effects inverse-variance model with the Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman adjustment. The pooled effect size for r was classified as small (≤0·10), moderate (0·10–0·37) or large (≥0·37)(Reference McGrath and Meyer15). All analyses were performed using the admetan routine(Reference Fisher16) within version 16.1 of STATA (STATA Corp.). A P value of <0·05 was considered a threshold for statistical significance.

Synthesis of results

For each meta-analysis, heterogeneity across studies was calculated using the total variance (Q), the df and the inconsistency index (I 2)(Reference Higgins, Thompson and Deeks17), considering I 2 values of <25, 25–75 and ≥75 % as small, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively(Reference Higgins and Thompson18). Sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether any single study with extreme findings had an undue influence on the overall results.

Risk of bias across studies

In the different meta-analyses performed, small-study effect bias was assessed using the extended Egger’s regression test(Reference Egger, Smith and Schneider19).

Additional analysis

We identified potential moderator variables a priori. The variables were sex and age (children <12 years and adolescents ≥12 years of mean age), by stratifying meta-analyses by each of these factors.

Results

Study selection

In total, thirty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis(Reference Rosi, Giopp and Milioli10,Reference Arnaoutis, Georgoulis and Psarra20–Reference Galan-Lopez, Sánchez-Oliver and Ries57) . The reasons for exclusion based on full text are reported as online Supplementary material 2. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the number of studies excluded at each stage of the systematic review and meta-analysis is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Study selection.

Study characteristics

A total of thirty-nine studies reported endpoints, and details of these are listed in Table 1. Most of the studies were cross-sectional in nature except for two that included a prospective design (however, we used only data from baseline)(Reference Grao-Cruces, Fernández-Martínez and Nuviala23,Reference Roccaldo, Censi and D’Addezio43) . The studies involved a total sample of 565 421 youth with ages between 8 and 17 years (mean age, 12·4 years). All studies included males and females (51 and 49 %, respectively). Sample sizes across studies ranged from 298(Reference Mieziene, Emeljanovas and Novak35) to 335 810 participants(Reference Arnaoutis, Georgoulis and Psarra20).

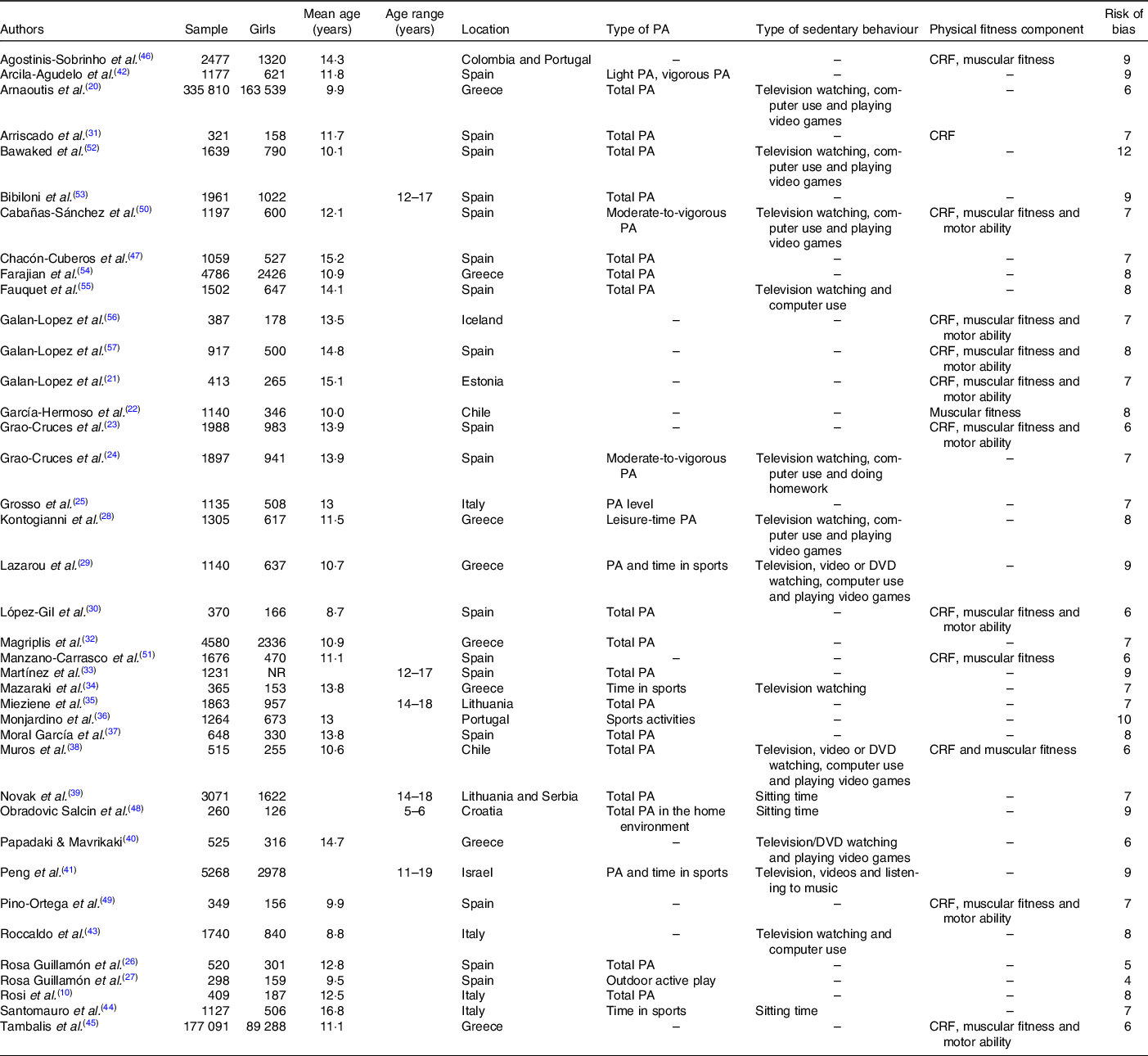

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies

PA, physical activity; CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness.

Seventeen studies included participants from Spain(Reference Galan-Lopez, Domínguez and Pihu21–Reference Grao-Cruces, Nuviala and Fernández-Martínez24,Reference Rosa Guillamón, Carrillo López and García Cantó26,Reference Kontogianni, Vidra and Farmaki28,Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala31,Reference Magriplis, Farajian and Pounis32,Reference Mazaraki, Tsioufis and Dimitriadis34,Reference Mieziene, Emeljanovas and Novak35,Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado38,Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki40,Reference Santomauro, Lorini and Tanini44,Reference Bibiloni, Pich and Córdova53,Reference Fauquet, Sofi and López-Guimerà55–Reference Galan-Lopez, Sánchez-Oliver and Ries57) , eight from Greece(Reference Arnaoutis, Georgoulis and Psarra20,Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi25,Reference Monjardino, Lucas and Ramos36,Reference Moral García, Agraso López and Pérez Soto37,Reference Peng, Goldsmith and Berry41,Reference Chacón-Cuberos, Zurita-Ortega and Martínez-Martínez47,Reference Manzano-Carrasco, Felipe and Sanchez-Sanchez51) , four from Italy(Reference Rosi, Giopp and Milioli10,Reference Martínez, Llull and Del Mar Bibiloni33,Reference Pino-Ortega, De La Cruz-Sánchez and Martínez-Santos49,Reference Cabanas-Sánchez, Martínez-Gómez and Izquierdo-Gómez50) and one from Chile(Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Moraiti45), Croatia(Reference Farajian, Risvas and Karasouli54), Iceland(Reference Rosa Guillamon, Garcia Canto and Rodríguez García27), Estonia(Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Matalas29) and Lithuania(Reference Arcila-Agudelo, Ferrer-Svoboda and Torres-Fernàndez42). Two studies were multi-national (Lithuania and Serbia(Reference Agostinis-Sobrinho, Santos and Rosário46), Colombia and Portugal(Reference Bawaked, Gomez and Homs52)).

Measurements

Nine of the thirty-nine studies in the systematic review reported PA through several instruments(Reference García-Hermoso, Vegas-Heredia and Fernández-Vergara22,Reference Rosa Guillamón, Carrillo López and García Cantó26,Reference Magriplis, Farajian and Pounis32,Reference Martínez, Llull and Del Mar Bibiloni33,Reference Monjardino, Lucas and Ramos36,Reference Moral García, Agraso López and Pérez Soto37,Reference Cabanas-Sánchez, Martínez-Gómez and Izquierdo-Gómez50,Reference Manzano-Carrasco, Felipe and Sanchez-Sanchez51) (e.g. the Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity Screening Measure), fifteen used validated questionnaires like the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children(Reference Galan-Lopez, Domínguez and Pihu21,Reference Grao-Cruces, Fernández-Martínez and Nuviala23,Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi25,Reference Mazaraki, Tsioufis and Dimitriadis34,Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado38,Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Moraiti45) or adolescents(Reference Rosi, Giopp and Milioli10,Reference Bibiloni, Pich and Córdova53) , the International Physical Activity Questionnaire(Reference Grao-Cruces, Nuviala and Fernández-Martínez24,Reference Novak, Štefan and Prosoli39,Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki40,Reference Arcila-Agudelo, Ferrer-Svoboda and Torres-Fernàndez42,Reference Santomauro, Lorini and Tanini44,Reference Agostinis-Sobrinho, Santos and Rosário46) , the Krece Plus test(Reference Mieziene, Emeljanovas and Novak35) and accelerometry(Reference Galan-Lopez, Ries and Gisladottir56).

Regarding screen time, most studies reported data on overall screen media time or frequency, mainly television viewing, computer use and video game playing. Four studies used sitting time(Reference Agostinis-Sobrinho, Santos and Rosário46,Reference Cabanas-Sánchez, Martínez-Gómez and Izquierdo-Gómez50,Reference Farajian, Risvas and Karasouli54,Reference Galan-Lopez, Ries and Gisladottir56) as sedentary behaviour.

Finally, components of physical fitness used were the CRF(Reference Galan-Lopez, Domínguez and Pihu21,Reference Rosa Guillamon, Garcia Canto and Rodríguez García27–Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Matalas29,Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala31,Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado38,Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Moraiti45,Reference Manzano-Carrasco, Felipe and Sanchez-Sanchez51,Reference Bawaked, Gomez and Homs52,Reference Galan-Lopez, Sánchez-Oliver and Ries57) , muscular fitness(Reference Rosa Guillamon, Garcia Canto and Rodríguez García27–Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala31,Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado38,Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Moraiti45,Reference Manzano-Carrasco, Felipe and Sanchez-Sanchez51,Reference Bawaked, Gomez and Homs52,Reference Galan-Lopez, Sánchez-Oliver and Ries57) and speed–agility(Reference Rosa Guillamon, Garcia Canto and Rodríguez García27–Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Matalas29,Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala31,Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado38,Reference Manzano-Carrasco, Felipe and Sanchez-Sanchez51) measured with the EUROFIT(Reference Manzano-Carrasco, Felipe and Sanchez-Sanchez51,Reference Fauquet, Sofi and López-Guimerà55) or ALPHA fitness battery(Reference Rosa Guillamon, Garcia Canto and Rodríguez García27–Reference Lazarou, Panagiotakos and Matalas29,Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala31,Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado38,Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Moraiti45,Reference Galan-Lopez, Ries and Gisladottir56,Reference Galan-Lopez, Sánchez-Oliver and Ries57) tests (Table 1).

Risk of bias within studies

All thirty-nine studies met at least four criteria and were considered to have moderate methodological quality. The average score was 7·5/14·0 (online Supplementary material 3).

Synthesis of results

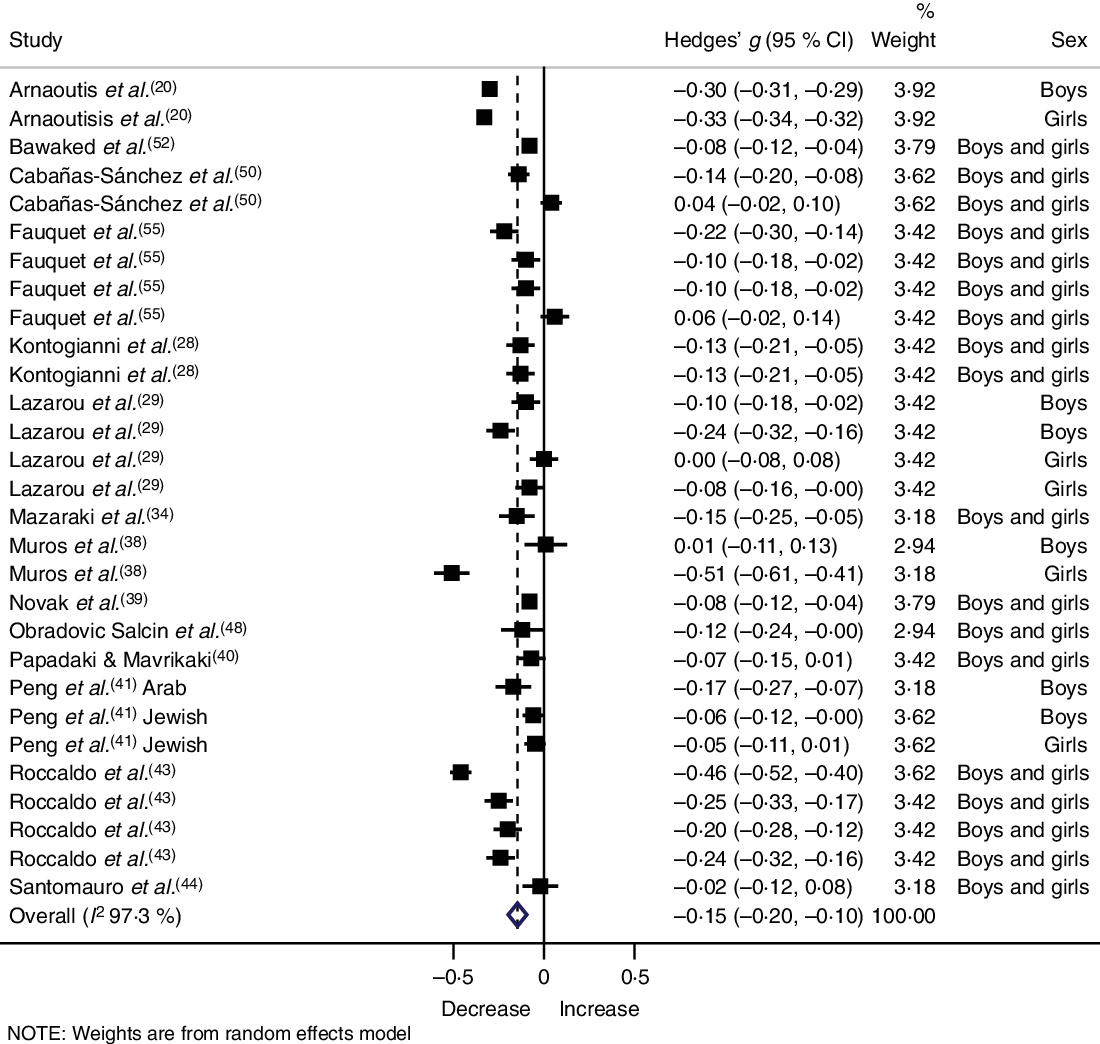

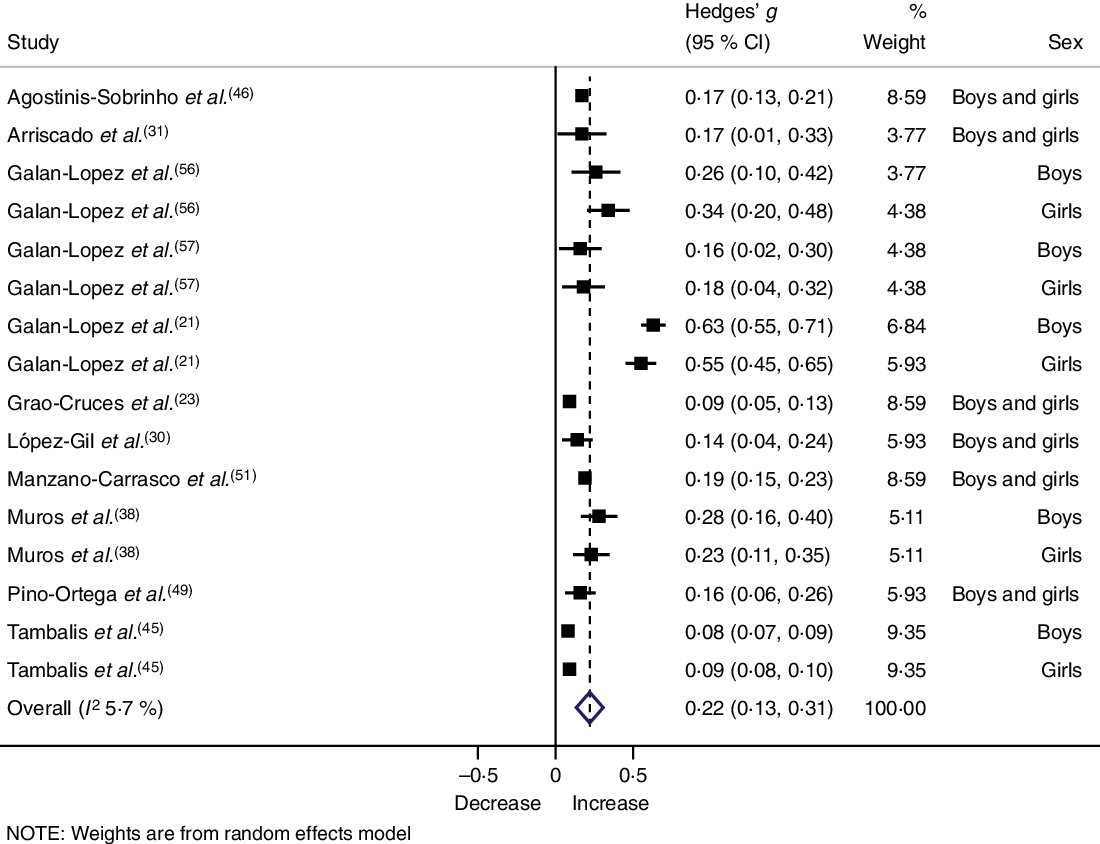

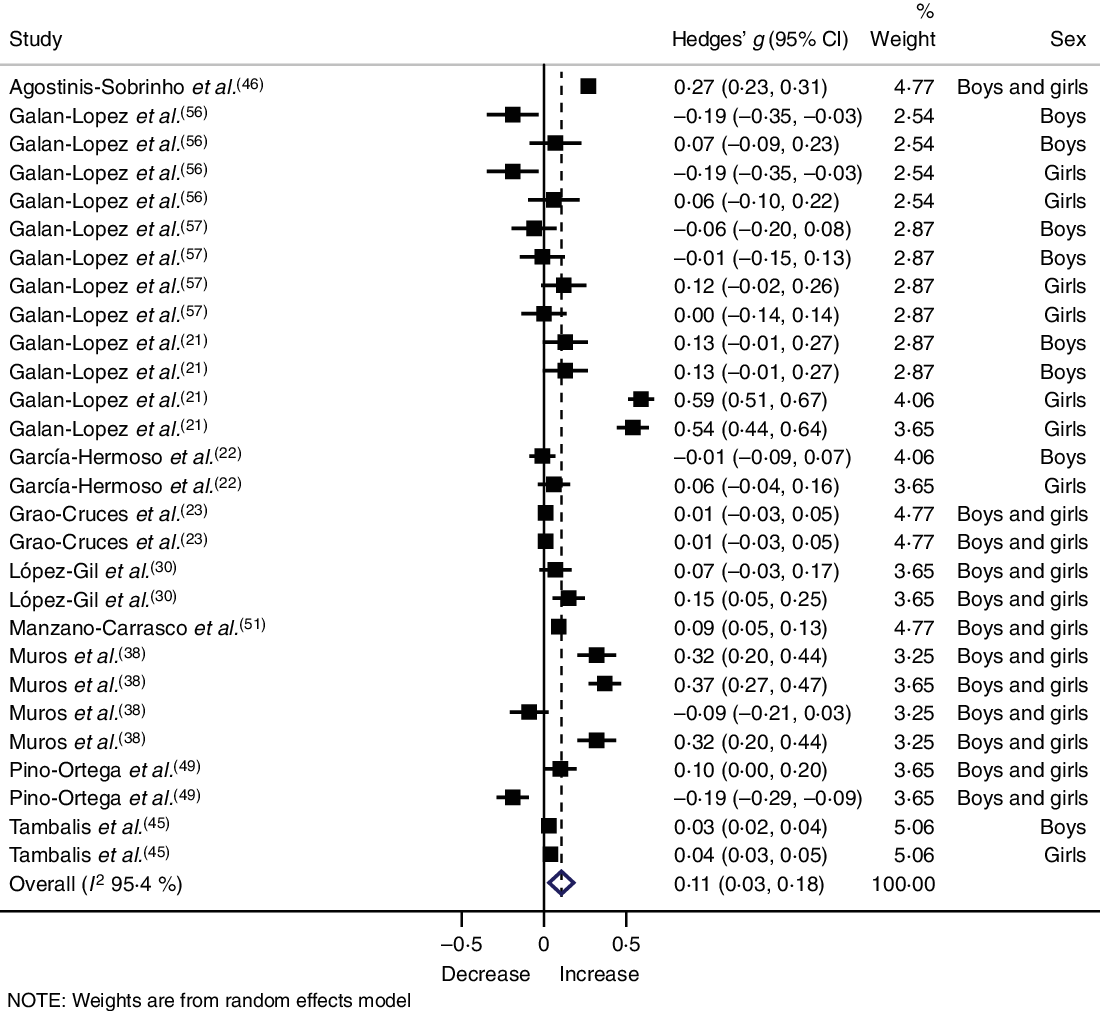

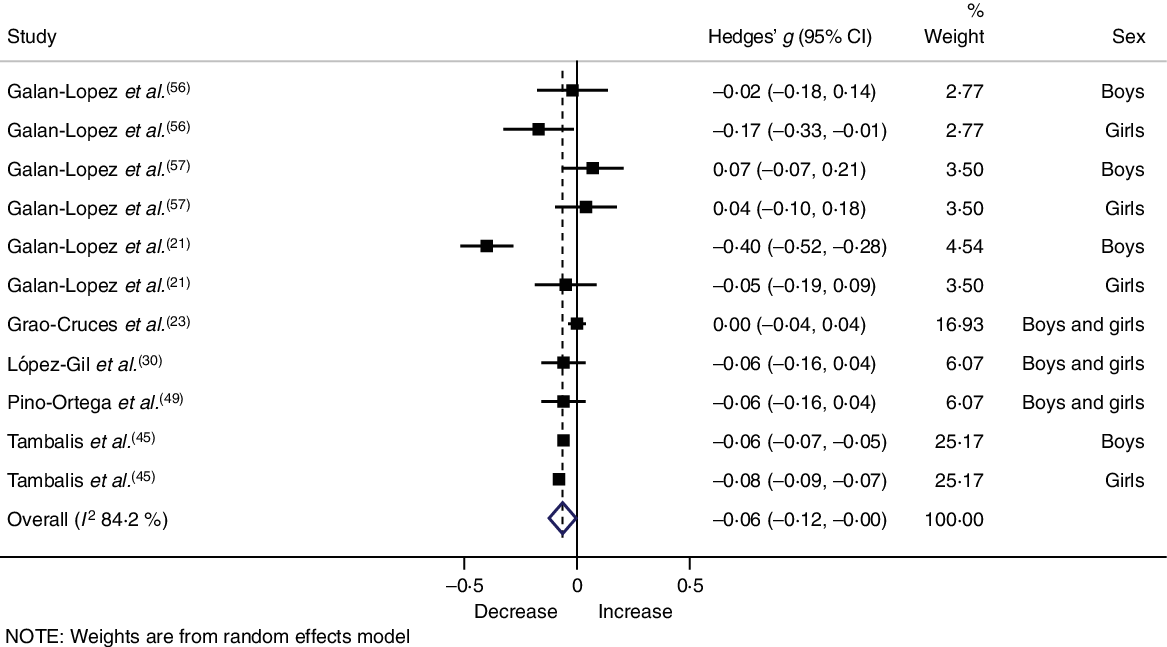

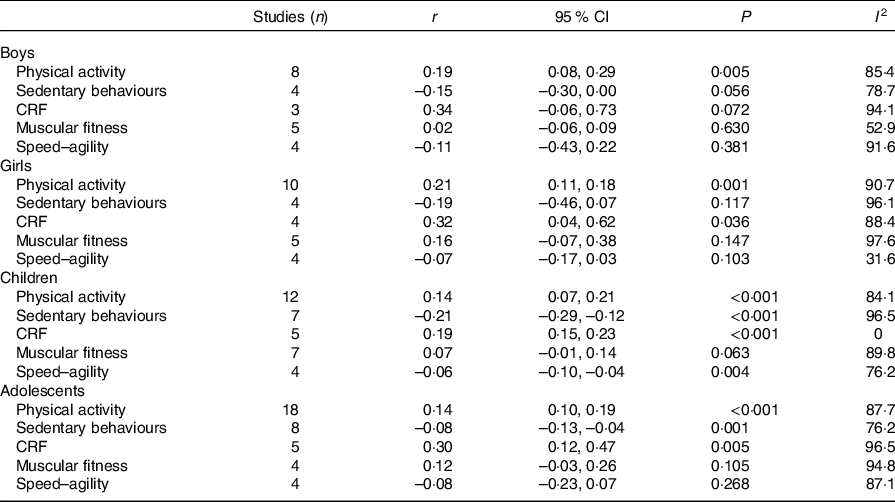

Figs. 2–6 show the synthesis of results. There was a weak-to-moderate direct relationship between adherence to the MD and PA (r 0·14; 95 % CI 0·11, 0·17; I 2 88·6), CRF (r 0·22; 95 % CI 0·13, 0·31; I 2 95·7) and muscular fitness (r = 0·11; 95 % CI 0·03, 0·18; I 2 95·4), and a weak-to-moderate negative relationship with sedentary behaviour (r –0·15; 95 % CI –0·20, –0·10; I 2 97·3) and speed–agility (r –0·06; 95 % CI –0·12, –0·01; I 2 84·2).

Fig. 2. Forest plot showing the correlation of Mediterranean diet adherence and physical activity for each study. Squares represent pooled effect size for each subgroup analysis, and the diamond represents the overall pooled effect size.

Fig. 3. Forest plot showing the correlation of Mediterranean diet adherence and sedentary behaviours for each study. Squares represent pooled effect size for each subgroup analysis, and the diamond represents the overall pooled effect size.

Fig. 4. Forest plot showing the correlation of Mediterranean diet adherence and cardiorespiratory fitness for each study. Squares represent pooled effect size for each subgroup analysis, and the diamond represents the overall pooled effect size.

Fig. 5. Forest plot showing the correlation of Mediterranean diet adherence and muscular fitness for each study. Squares represent pooled effect size for each subgroup analysis, and the diamond represents the overall pooled effect size.

Fig. 6. Forest plot showing the correlation of Mediterranean diet adherence and speed–agility (lower values represent higher performance) for each study. Squares represent pooled effect size for each subgroup analysis, and the diamond represents the overall pooled effect size.

The results remained significant after controlling for sex and age (children or adolescents) in PA (Table 2). Also, there was a significant slightly higher correlation between adherence to the MD and sedentary behaviour in children (r –0·21; 95 % CI –0·29, –0·12; I 2 96·5) and CRF in adolescents (r 0·30; 95 % CI 0·12, 0·47; I 2 96·5).

Table 2. Subgroup analysis of the association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and physical activity, sedentary behaviour and physical fitness components according to sex and age

(Correlation coefficients (r) and 95 % confidence intervals)

CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Funnel plots and the Egger asymmetry test indicated statistically significant publication bias for PA (effect size = 1·75; 95 % CI 0·58, 2·91; P < 0·001), sedentary behaviour (effect size = 5·22; 95 % CI 3·24, 7·32; P < 0·001) and CRF (effect size = 3·38; 95 % CI 1·48, 5·27; P = 0·002) (online Supplementary material 4).

Finally, sensitivity analyses were carried out by sequentially removing one study from the data set to elucidate the influence of individual studies on the analysis. Results remained consistent across all deletions.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to synthesise the evidence on the cross-sectional associations between adherence to the MD, PA, sedentary behaviour and physical fitness levels in children and adolescents. Our analyses showed small-to-moderate positive relationships between adherence to the MD, PA, CRF and muscular fitness and a negative relationship with sedentary behaviours and speed–agility. Overall, the meta-analysis indicates that youths with higher adherence to the MD are more likely to be physically active, fit and have a less sedentary lifestyle. However, the findings should be interpreted while keeping in mind the heterogeneity between studies in the associations, exposure and outcomes assessment and publication bias.

A recent review by Iaccarino Idelson et al. (Reference Iaccarino Idelson, Scalfi and Valerio1) suggested a positive association between adherence to the MD and PA levels. In this line, our meta-analytic findings suggest a moderate direct association between them, independent of sex and age. One might speculate about four possible hypotheses underlying the relationships between the two behaviours: (i) it is possible that MD adherence influences PA by allowing those youths who eat properly to be more physically active by providing them with the necessary nutrients(Reference Petrie, Stover and Horswill58). For example, it has been reported that the higher energy expenditure of active children and adolescents requires higher intake of essential nutrients(Reference Kelishadi, Ardalan and Gheiratmand59), which requires a higher consumption of carbohydrates, vitamins and quality proteins, all provided by adequate MD adherence; (ii) better eating habits seem to be linked with some personality traits such as self-efficacy and self-regulation, which is a motive to get more involved in PA among children and adolescents(Reference López-Gil, Oriol-Granado and Izquierdo60); (iii) specific behavioural and environmental factors such as the school environment and the influence of peer groups often result in the clustering of behavioural habits, meaning that youths who are more active tend to develop other healthy habits such as consuming a healthy diet(Reference Leech, McNaughton and Timperio61) and (iv) both behaviours and their relationship could be linked to the family environment(Reference Farajian, Risvas and Karasouli54). With respect to the latter, there is some evidence to indicate the importance of parental education in the healthy eating choices of their children(Reference Arcila-Agudelo, Ferrer-Svoboda and Torres-Fernàndez42). Likewise, it has been determined that socio-economic status is one of the most important determinants of both MD adherence(Reference Iaccarino Idelson, Scalfi and Valerio1) and PA among young people(Reference O’Donoghue, Kennedy and Puggina62).

With respect to sedentary behaviour, our analysis showed that higher adherence to the MD was related to lower sedentary lifestyle, usually assessed as screen time and predominantly television viewing and computer use. These relationships have been reiterated by other authors, suggesting that children with healthy eating habits, assessed with the question ‘Do you think this child typically eats healthy meals?’, are engaged in fewer sedentary behaviours(Reference Shi, Tubb and Fingers63). There are several possible explanations for this result: (i) screen time viewing, mainly television use, is inversely related to healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables and is positively associated with a higher intake of energy-dense snacks and drinks, fast foods, total energy intake and energy from fat in youth(Reference Avery, Anderson and McCullough64); (ii) television viewing and exposure to food advertising are connected, in a positive manner, to unhealthy food habits in children and adolescents(Reference Lobstein and Dibb65). In this context, some authors disagree between television and computer sedentarism, suggesting that using personal computers involves lower nutritional risk, as hands are usually engaged and therefore not free for the consumption of unhealthy foods(Reference Rey-López, Vicente-Rodríguez and Biosca66). In contrast to these earlier findings, our meta-analysis showed similar relationship between MD and television (r –0·14; 95 % CI –0·22, –0·05) and computer use (r –0·19; 95 % CI –0·33, –0·05) (data not shown).

Our study also shows that adherence to the MD is significantly associated with higher CRF, muscular fitness and speed–agility levels. These results are similar to those reported by several studies which used other eating habits questionnaires(Reference Thivel, Aucouturier and Isacco7,Reference Cuenca-García, Ruiz and Ortega8) . An example of this is the study carried out by Thivel et al. (Reference Thivel, Aucouturier and Isacco7) who reported that CRF and muscular fitness in French schoolchildren were associated with healthy eating habits. In a similar case in ten European cities, the authors suggested that adolescents who skipped breakfast were less likely to achieve elevated CRF measurements in comparison with those who consumed breakfast(Reference Cuenca-García, Ruiz and Ortega8). According to this, it could be proposed that a well-balanced diet, providing adequate energy sources throughout the day, rich in all essential nutrients and natural antioxidants, low in saturated fat, and based on an abundant consumption of fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, nuts and olive oil, would yield great benefits on physical fitness during childhood and adolescence(Reference Arnaoutis, Georgoulis and Psarra20).

Practice implications

Improving dietary habits towards those of the MD could be associated with higher physical fitness and PA in youth, lower sedentary behaviours(Reference Peters, Sutton and Jones67) and better health in general. Understanding the behaviours associated with adherence to MD in the young population could be essential for the appropriate, specific design of public health interventions that will contribute to early adoption of healthy habits to reduce the impact of Western dietary patterns.

Limitations and strengths

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the association between the MD and healthy habits among children and adolescents, including a total of 562 764 youth in the analyses.

The present meta-analysis has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the included studies prevents causal inferences and can be more susceptible to biases (e.g. selection bias, information bias, etc.). Reverse causality could also be true. However, a prospective study included in our meta-analysis confirms results on PA and sedentary behaviours(Reference Grao-Cruces, Fernández-Martínez and Nuviala23). Second, in most studies, PA, dietary habits and sedentary time were self-reported and could potentially be subject to socially desirable reporting bias. Also, the included studies measured PA, sedentary behaviours and physical fitness using a wide variety of different tools. Third, most of the studies did not consider potential confounding factors such as socio-economic status and/or parental education. Finally, the results indicate publication bias for PA, sedentary behaviour and CRF. However, due to between-study heterogeneity, we are unable to conclude whether the asymmetry in the plot is due to heterogeneity between studies or publication bias(Reference García-Hermoso, Saavedra and Ramírez-Vélez68).

In conclusion, our findings have significant implications for the understanding of how MD is related to behavioural outcomes among youth. In general, it seems that lifestyle factors could interact with each other synergistically. The lack of experimental and prospective studies found in our meta-analysis suggests that the overall body of evidence is weak and further research is needed.

Acknowledgements

A. G. H. is a Miguel Servet Fellow (Instituto de Salud Carlos III – FSE, CP18/0150). R. R.-V. is funded in part by a Postdoctoral Fellowship Resolution ID 420/2019 of the Universidad Pública de Navarra.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

A. G. H., Y. E., J. F. L. G., R. R. V., J. O. and M. I. developed the concept and drafted the manuscript. A. G. H., Y. E. and R. R. V. prepared the tables and figures and completed the scoping review. A. G. H., Y. E. and M. I. contributed to data preparation and modelling. All other authors provided data, developed models, reviewed results, provided guidance on methodology or reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary materials referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520004894