Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a mood disorder characterised by recurrent depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes (Goodwin and Jamison, Reference Goodwin and Jamison2007), with different subtypes, such as bipolar I (BD-I), bipolar II (BD-II) and BD Not Otherwise Specified (BD-NOS) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The lifetime prevalence of BD is estimated to be 2.4% worldwide (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, Jin, He, Kessler, Lee, Sampson, Viana, Andrade, Hu and Karam2011). Due to its complex and varying clinical presentations, BD is often misdiagnosed for other psychiatric disorders (Berk et al., Reference Berk, Dodd, Callaly, Berk, Fitzgerald, De Castella, Filia, Filia, Tahtalian and Biffin2007), such as major depression (Perlis, Reference Perlis2005) and substance abuse disorder (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Shetty, Jackson, Broadbent, Stewart, Boydell, McGuire and Taylor2015), which results in poor treatment outcomes and increased risk of suicide (Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Cruz, Franco, Haro, Bertsch, Reed, Aarre, Sanchez-Moreno and Vieta2010).

Suicide attempt (SA) is an important predictor of completed suicide (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Gates, Whitaker and Cotton1985; Harkavy-Friedman et al., Reference Harkavy-Friedman, Restifo, Malaspina, Kaufmann, Amador, Yale and Gorman1999; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock and Wang2005). Compared to the general population, BD patients are at a higher risk of suicide (Nierenberg et al., Reference Nierenberg, Gray and Grandin2001; Plans et al., Reference Plans, Barrot, Nieto, Rios, Schulze, Papiol, Mitjans, Vieta and Benabarre2019). A prospective study found that BD had the highest risk of suicide of all psychiatric diagnoses (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Beck, Steer and Grisham2000). The risk of SA in BD is approximately 30-fold higher than that in the general population (Goodwin and Jamison, Reference Goodwin and Jamison2007), and approximately 0.9% of BD patients attempt suicide every year (Beyer and Weisler, Reference Beyer and Weisler2016). Further, the combination of BD and history of SA is probably the strongest predictor of completed suicide (Antypa et al., Reference Antypa, Antonioli and Serretti2013). Approximately 30–50% of BD patients have a lifetime history of SA, of whom 15–20% eventually died by suicide (Baldessarini et al., Reference Baldessarini, Pompili and Tondo2006; Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Pompili, Serafini, Montebovi, Campi, Dome, Duleba, Girardi and Rihmer2012). In a previous study, more lethal methods of SA and suicide were observed in BD patients than in the general population (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Hunkeler, Fireman, Lee and Savarino2007). Thus, suicide and SA account for a considerable proportion of disease burden in BD (Angst, Reference Angst2004).

A host of demographic and clinical factors are related to SA in BD, including female gender, single and divorced marital status, history of sexual abuse, younger age of onset, depressive phase, severe depressive symptoms, frequent hospitalisation for depression, BD-I subtype, rapid cycling, comorbid substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders, past history of SA and suicide in first-degree relatives (Leverich et al., Reference Leverich, Altshuler, Frye, Suppes, Keck, McElroy, Denicoff, Obrocea, Nolen, Kupka, Walden, Grunze, Perez, Luckenbaugh and Post2003; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Sutton, Haw, Sinclair and Harriss2005; Shabani et al., Reference Shabani, Teimurinejad, Kokar, Ahmadzad Asl, Shariati, Mousavi Behbahani, Ghasemzadeh, Hasani, Taban, Shirekhoda, Ghorbani, Tat, Nohesara and Shariat2013; Schaffer et al., Reference Schaffer, Isometsä, Azorin, Cassidy, Goldstein, Rihmer, Sinyor, Tondo, Moreno and Turecki2015a, Reference Schaffer, Isometsä, Tondo, Moreno, Turecki, Reis, Cassidy, Sinyor, Azorin and Kessing2015b; Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Na, Geske, McElroy, Frye and Biernacka2018). Epidemiological studies on the prevalence of SA in BD are fraught with methodological limitations resulting in inconsistent findings (Novick et al., Reference Novick, Swartz and Frank2010; Latalova et al., Reference Latalova, Kamaradova and Prasko2014; Tondo et al., Reference Tondo, Pompili, Forte and Baldessarini2016). In previous reviews, relying on only one database (PsycINFO) (Novick et al., Reference Novick, Swartz and Frank2010) or inclusion of randomised control trials with stringent entry criteria are just two examples of methodological shortcomings that limit the generalisability of the findings (Tondo et al., Reference Tondo, Pompili, Forte and Baldessarini2016).

In order to inform health care policy and frontline mental health professionals in their attempt to reduce suicide risk, it is important to understand the patterns of SA and their related factors. In view of the large number of recently published epidemiological studies of SA in BD (Passos et al., Reference Passos, Jansen, Cardoso, Colpo, Zeni, Quevedo, Kauer-Sant'Anna, Zunta-Soares, Soares and Kapczinski2016; Baldessarini et al., Reference Baldessarini, Innamorati, Erbuto, Serafini, Fiorillo, Amore, Girardi and Pompili2017; Bellivier et al., Reference Bellivier, Belzeaux, Scott, Courtet, Golmard and Azorin2017; Bezerra et al., Reference Bezerra, Galvao-de-Almeida, Studart, Martins, Caribe, Schwingel and Miranda-Scippa2017; Cremaschi et al., Reference Cremaschi, Dell'Osso, Vismara, Dobrea, Buoli, Ketter and Altamura2017; Kattimani et al., Reference Kattimani, Subramanian, Sarkar, Rajkumar and Balasubramanian2017; Altamura et al., Reference Altamura, Buoli, Cesana, Dell'Osso, Tacchini, Albert, Fagiolini, de Bartolomeis, Maina and Sacchetti2018; Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Na, Geske, McElroy, Frye and Biernacka2018; Duko and Ayano, Reference Duko and Ayano2018), this systematic review and meta-analysis explored the prevalence of SA in BD and its associated factors. The main hypothesis of the study was that bipolar patients would have a significantly higher prevalence of SA compared to the general population. In order to make the sample more representative, only epidemiological studies were included in this meta-analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and MOOSE recommendations (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000). The registration number of this protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) is CRD42018108290. Two authors (MD and LL) searched the PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE and Web of Science databases from their inception through 11 June 2018 using the following search terms: attempted suicide, suicide attempt*, bipolar disorder, manic-depressive disorder, affective disorder, mood disorder, bipolar depression, bipolar affective, hypomania, mania, manic, epidemiology, cross-sectional study, cohort study, observational study, prevalence, rate, percentage, proportion. References of review papers were also searched to identify additional articles. Figure 1 displays the process of the selection of studies for the meta-analysis.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study selection.

Study selection

Two authors (MD and LL) independently screened the title and abstract of relevant studies and then read their full text for eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: (1) BD diagnosed according to any international or local diagnostic criteria; (2) available meta-analysable data on SA with one or more of the following timeframes: lifetime, 1-year, 1-month, current episode and from illness onset; (3) cross-sectional or cohort studies (only baseline data of cohort studies were analysed); (4) publication in English. Studies were excluded if they (1) were intervention studies or reviews; (2) had very small sample size (n < 100) (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Holm Hansen, Martin, Sawhney, Thekkumpurath, Beale, Symeonides, Wall, Murray and Sharpe2013; Matte et al., Reference Matte, Pizzichini, Hoepers, Diaz, Karloh, Dias and Pizzichini2016) or special populations, such as adolescent or elderly samples; (3) were registry-based studies or extracted data from medical records. If multiple papers were published based on the same dataset, only the study with the largest sample size was analysed. Several papers (such as Carballo et al., Reference Carballo, Harkavy-Friedman, Burke, Sher, Baca-Garcia, Sullivan, Grunebaum, Parsey, Mann and Oquendo2008; Elizabeth Sublette et al., Reference Elizabeth Sublette, Carballo, Moreno, Galfalvy, Brent, Birmaher, John Mann and Oquendo2009; Studart et al., Reference Studart, Galvao-de Almeida, Bezerra, Caribe, Afonso, Daltro and Miranda-Scippa2016) reported overlapping data with the included studies. The corresponding authors were contacted for clarification, but since no reply was received, therefore these studies were excluded. Any uncertainty in the literature search and study selection was resolved by a discussion with a senior researcher (YTX).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the included studies covering the first author, publication year, time of survey, study site, sampling method, study design, sample size, mean age, proportion of males, diagnostic criteria of BD, patient source, assessment and timeframe of SA. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors (MD and LL).

Study quality was assessed using the quality assessment instrument for epidemiological studies (Boyle, Reference Boyle1998; Loney et al., Reference Loney, Chambers, Bennett, Roberts and Stratford1998); which has the total score ranging from 1 (lowest quality) to 8 (highest quality) points. The eight domains of the instrument are: (1) Target population is clearly defined. (2) Probability or entire population sampling is used. (3) Response rate is >70%. (4) Non-responders are clearly described. (5) Sample is representative of the target population. (6) Data collection methods are standardised. (7) Validated criteria are used to assess the presence of disease. (8) Estimates of prevalence are given with confidence intervals and detailed by subgroup (if applicable). Studies with a total score of 7–8 were considered as high quality, 4–6 as moderate quality and 0–3 as low quality (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhang, Zhu, Zhu and Guo2016).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA), Version 2.0 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA) and STATA, Version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). A random-effect model was applied to calculate the overall prevalence and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed with the I 2 statistic. Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies one by one to explore the impact of each study on the overall results. Publication bias was evaluated with funnel plots and the Begg regression asymmetry test. In order to examine the moderating effects caused by demographic and clinical variables on the results, subgroup analyses for categorical variables (rapid cycling, gender, source of patients, income level, region and study design) and meta-regression analyses for continuous variables (per cent of BD subtype, sample size, mean age, illness duration and age of onset) were performed. If the number of studies was <10, subgroup analyses were conducted for continuous variables, using the median splitting method (Higgins and Green, Reference Higgins and Green2008). All the tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The search initially identified 3451 articles from the target databases and 12 additional articles from other sources (Fig. 1). Altogether, 79 studies covering 33 719 patients met study entry criteria (online Supplementary Table S1), including 58 cross-sectional and 21 cohort studies published between 1985 and 2018. Twenty, six and four studies employed consecutive, convenience and random sampling, respectively. In terms of diagnosis, 71 and four studies applied the DSM and Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Endicott and Robins1978), respectively, and one study each used the ICD, the DSM or/and ICD, DSM or/and RDC, the Affective Disorder Evaluation (ADE) (Sachs et al., Reference Sachs, Thase, Otto, Bauer, Miklowitz, Wisniewski, Lavori, Lebowitz, Rudorfer and Frank2003). The mean age of the whole sample ranged between 29.0 and 55.8 years, and then proportion of males ranged from 23.3 to 72.1%. Seventy-five of the 79 studies reported lifetime prevalence, three studies reported 1-year prevalence and three reported current episode prevalence of SA. The total score of quality assessment ranged from 4 to 8, with six studies rated as of high quality, and 73 studies as of moderate quality (online Supplementary Table S3).

Pooled prevalence of SA

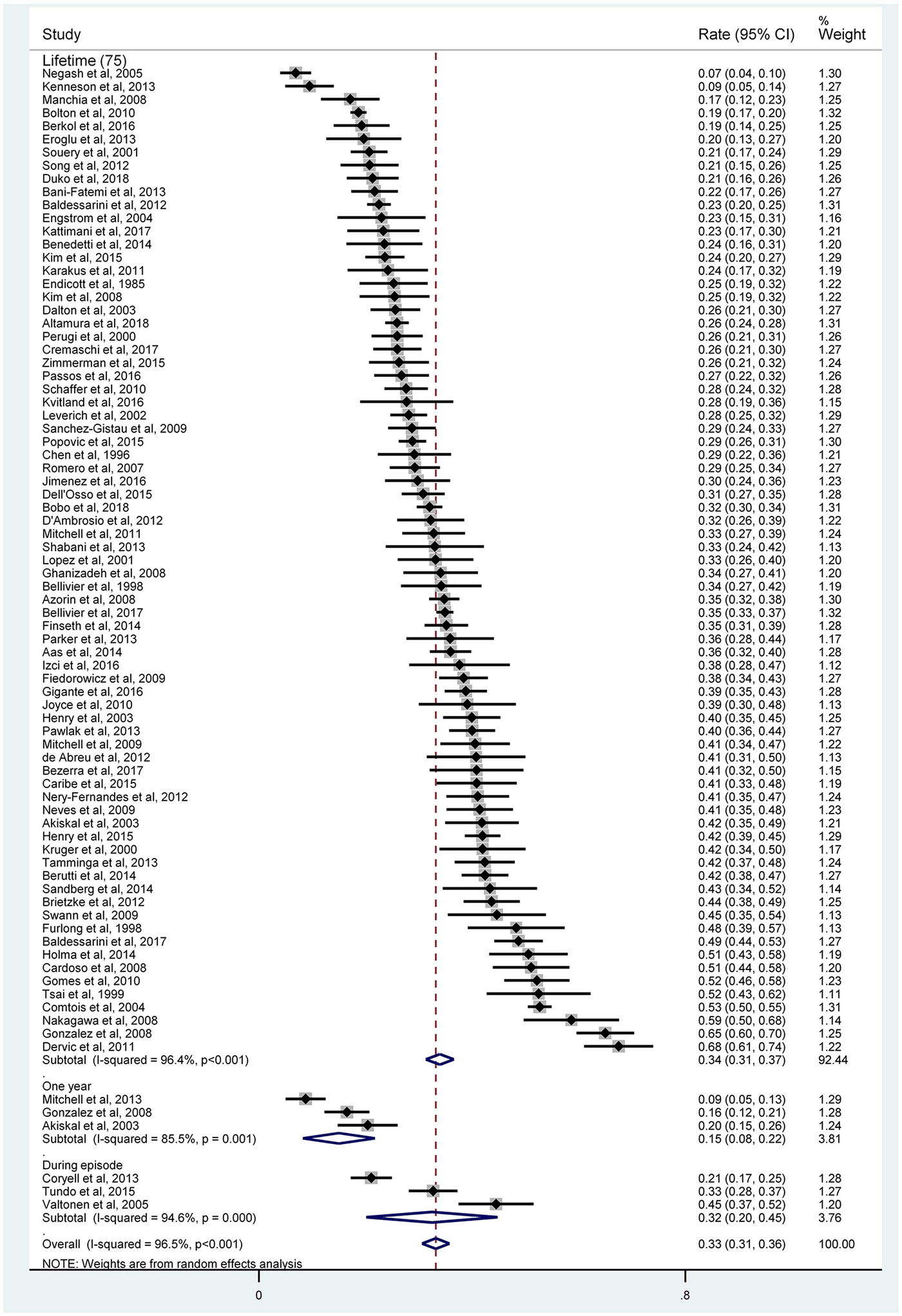

The pooled lifetime prevalence of SA in BD was 33.9% (95% CI 31.3–36.6%; I 2 = 96.4%), 1-year prevalence of SA was 15.0% (95% CI 8.2–21.8%; I 2 = 85.5%) and current episode prevalence of SA was 32.5% (95% CI 20.1–44.8%; I 2 = 94.6%) (Fig. 2). None of the included studies reported 1-month prevalence or prevalence from illness onset.

Fig. 2. Forest plot of suicide attempt.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

When sensitivity analysis omitted each study one by one, there was no outlying study that could have significantly changed the lifetime prevalence of SA (online Supplementary Fig. S1). Neither the funnel plot nor Begg's test found significant publication bias with respect to the lifetime prevalence of SA (z = 0.76, p = 0.44) (online Supplementary Fig. S2).

Subgroup and meta-regression analyses

The results of subgroup analyses are shown in Table 1. Gender, income level, rapid cycling and region were significantly associated with lifetime prevalence of SA, while study design was significantly associated with its 1-year prevalence. Specifically, the lifetime prevalence of SA in rapid cycling BD (47.0%) was significantly higher than in the non-rapid cycling subtype (30.2%) (p < 0.001). Female gender (34.4%) was significantly more prevalent than male gender (26.4%) (p = 0.002) in SA in BD. The prevalence of SA in high- (33.7%) and middle-income countries (34.7%) was significantly higher than in low-income countries (12.8%) (p = 0.003). The prevalence of SA was highest in the Americas (37.0%) and lowest in Africa (12.8%) (p = 0.01). The 1-year prevalence of SA reported in cohort studies (18.2%) was significantly higher than in cross-sectional studies (8.8%) (p = 0.003).

Table 1. Subgroup analyses of SA prevalence in bipolar disorder

BD, bipolar disorder; NOS, Not Otherwise Specified; NRC, non-rapid cycling; RC, rapid cycling; SA, suicide attempt.

a Test of heterogeneity within subgroups.

b Test of prevalence of SA across subgroups.

c Median splitting method was used.

Bold values = p < 0.05.

In meta-regression analyses, the proportions of BD-I (B = 0.002, z = 3.9, p < 0.001) and BD-NOS (B = 0.01, z = 6.3, p < 0.001) were positively, while sample size (B = −0.00004, z = −3.5, p < 0.001) and the proportion of BD-II (B = −0.003, z = −4.9, p < 0.001) were negatively associated with lifetime prevalence of SA. Mean age (B = −0.004, z = −1.4, p = 0.13), illness duration (B = −0.004, z = −0.8, p = 0.40) and age of onset (B = −0.004, z = −0.7, p = 0.46) were not significantly associated with lifetime prevalence of SA.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, the lifetime prevalence of SA in BD (33.9%; 95% CI 31.3–36.6%) was significantly higher than in the general population (0.8%; 95% CI 0.7–0.9%) (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Haro, Bernert, Brugha, de Graaf, Bruffaerts, Lepine, de Girolamo, Vilagut, Gasquet, Torres, Kovess, Heider, Neeleman, Kessler and Alonso2007; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Zhong, Xiang, Ungvari, Lai, Chiu and Caine2015) and in schizophrenia (14.6%; 95% CI 9.1–22.8%), but was only slightly higher than the figures found in major depression (31%; 95% CI 27–34%) (Howe et al., Reference Howe, Leung, Bani-Fatemi, Souza, Tampakeras, Zai, Kennedy, Strauss and De Luca2014; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wang, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng, Meng, Yuan, Wang and Xiang2017, Reference Dong, Zeng, Lu, Li, Ungvari, Ng, Chow, Zhang, Zhou and Xiang2018). The higher risk of SA in BD compared to major depression relates to the differences in clinical profile between both disorders (Szadoczky et al., Reference Szadoczky, Vitrai, Rihmer and Furedi2000). Impulsivity, a trait of BD (Tondo and Baldessarini, Reference Tondo and Baldessarini2005), is associated with both SA and suicide (Swann et al., Reference Swann, Dougherty, Pazzaglia, Pham, Steinberg and Moeller2005). In addition, several key factors contributing to SA, e.g. mixed state and depressive phase, are part of BD (Oquendo et al., Reference Oquendo, Waternaux, Brodsky, Parsons, Haas, Malone and Mann2000; Schaffer et al., Reference Schaffer, Isometsä, Azorin, Cassidy, Goldstein, Rihmer, Sinyor, Tondo, Moreno and Turecki2015a). However, the difference between BD and depression with regard to lifetime prevalence of SA did not reach a significant level (33.9%, 95% CI 31.3–36.6% v. 31%, 95% CI 27–34%) in a meta-analysis (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Zeng, Lu, Li, Ungvari, Ng, Chow, Zhang, Zhou and Xiang2018). Another review of 24 studies (Novick et al., Reference Novick, Swartz and Frank2010) reported the lifetime prevalence of SA (36.3% in BD-I and 32.4% in BD-II). However, in the Novick et al. review, only the PsycINFO database was searched yielding only 439 relevant hits and the prevalence estimates of SA in different timeframes were not reported. In contrast, the current meta-analysis more comprehensively covered the literature and examined the prevalence of SA in different timeframes. Novick et al. analysed randomised control trials with stringent entry criteria, which could lead to selection bias, while this meta-analysis included observational studies, thereby increasing the representativeness of the study sample. Furthermore, more sophisticated analyses including subgroup and sensitivity analyses were carried out in the present study.

The lifetime prevalence of SA was higher in females than in males, which is also found in previous studies (Tondo et al., Reference Tondo, Isacsson and Baldessarini2003, Reference Tondo, Pompili, Forte and Baldessarini2016). The possible reasons include relatively more frequent depressive episodes (Schneck et al., Reference Schneck, Miklowitz, Calabrese, Allen, Thomas, Wisniewski, Miyahara, Shelton, Ketter and Goldberg2004), rapid cycling BD (Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Vieta, Comes, Haro, Reed and Bertsch2008) and history of childhood physical and sexual abuse (Stefanello et al., Reference Stefanello, Cais, Mauro, Freitas and Botega2008) in female patients. Male BD patients are more likely to resort to more lethal methods of suicide (Pompili et al., Reference Pompili, Rihmer, Innamorati, Lester, Girardi and Tatarelli2009). Previous findings comparing the SA rate between BD-I and BD-II have been inconsistent. Higher SA rates in BD-I (Oquendo et al., Reference Oquendo, Currier, Liu, Hasin, Grant and Blanco2010; Antypa et al., Reference Antypa, Antonioli and Serretti2013; Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Na, Geske, McElroy, Frye and Biernacka2018) and in BD-II (Song et al., Reference Song, Yu, Kim, Hwang, Cho, Kim, Ha and Ahn2012; Holma et al., Reference Holma, Haukka, Suominen, Valtonen, Mantere, Melartin, Sokero, Oquendo and Isometsa2014) were reported, while other studies did not find significant differences between the two subtypes (Novick et al., Reference Novick, Swartz and Frank2010; Tondo et al., Reference Tondo, Pompili, Forte and Baldessarini2016). In the current meta-analysis, both BD-I and BD-NOS were positively associated while BD-II was negatively associated with lifetime prevalence of SA, which is similar to the findings of some (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Angst, Gerber-Werder and Gamma2005; Popovic et al., Reference Popovic, Vieta, Azorin, Angst, Bowden, Mosolov, Young and Perugi2015; Altamura et al., Reference Altamura, Buoli, Cesana, Dell'Osso, Tacchini, Albert, Fagiolini, de Bartolomeis, Maina and Sacchetti2018), but not all (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Angst, Gerber-Werder and Gamma2005; Neves et al., Reference Neves, Malloy-Diniz and Correa2009; Pawlak et al., Reference Pawlak, Dmitrzak-Weglarz, Skibinska, Szczepankiewicz, Leszczynska-Rodziewicz, Rajewska-Rager, Maciukiewicz, Czerski and Hauser2013) studies. The close association between the depressive phase and SA may be a reason for the diverse SA rates in different BD types (Schaffer et al., Reference Schaffer, Isometsä, Azorin, Cassidy, Goldstein, Rihmer, Sinyor, Tondo, Moreno and Turecki2015a). SA is more likely to occur during mixed states and depressive episodes in BD-I, and during depressive episodes in BD-II (Tondo et al., Reference Tondo, Baldessarini, Hennen, Minnai, Salis, Scamonatti, Masia, Ghiani and Mannu1999). Poorer insight and treatment adherence due to more frequent psychotic symptoms in BD-I (van der Werf-Eldering et al., Reference van der Werf-Eldering, van der Meer, Burger, Holthausen, Nolen and Aleman2011; Depp et al., Reference Depp, Harmell, Savla, Mausbach, Jeste and Palmer2014; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Mograbi, Camelo, Bifano, Wainstok, Silveira and Cheniaux2015) can lead to an increased risk of SA.

In the subgroup analyses, the lifetime rate of SA in rapid cycling BD (47.0%) was significantly higher than in non-rapid cycling BD (34.4%). Rapid cycling is a major risk factor of SA in BD (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Potash, McMahon, Simpson, Raymond Depaulo and Zandi2005), which is attributed to the younger age of onset, more illness severity, longer illness duration, poorer outcomes and higher risk of disability in rapid cycling BD (Kupka et al., Reference Kupka, Luckenbaugh, Post, Suppes, Altshuler, Keck, Frye, Denicoff, Grunze, Leverich, McElroy, Walden and Nolen2005; Mackin, Reference Mackin2005; Schneck et al., Reference Schneck, Miklowitz, Miyahara, Araga, Wisniewski, Gyulai, Allen, Thase and Sachs2008; Gigante et al., Reference Gigante, Barenboim, Dias, Toniolo, Mendonca, Miranda-Scippa, Kapczinski and Lafer2016). The lifetime rate of SA was significantly higher in high- and middle-income countries compared to low-income countries, and also higher in the Americas, Western Pacific and Europe than in Africa and South-East Asia. The discrepancy in SA rate across regions could be partly due to differences in health care services, ethnicity, and economic and sociocultural factors (Westman et al., Reference Westman, Hasselstrom, Johansson and Sundquist2003; Karch et al., Reference Karch, Barker and Strine2006). Westman et al. (Reference Westman, Hasselstrom, Johansson and Sundquist2003) have found that the place of birth and socioeconomic status were significantly associated with the risk of SA. The risk of suicide and associated factors were different between Caucasian and African Americans (Kung et al., Reference Kung, Liu and Juon1998). Studies of suicide in BD in low- and middle-income countries are few and far between, which can result in biased comparisons.

The sample size was negatively correlated to the lifetime prevalence of SA. Results of studies with small sample size are less reliable (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wang, Zhang, Ungvari, Ng, Meng, Yuan, Wang and Xiang2017). The higher 1-year prevalence of SA was found at baseline of cohort studies than in cross-sectional studies, while there was no group difference between lifetime and current episode prevalence between the two types of studies. Again, it is likely that the low number of cohort and cross-sectional studies resulted in unstable results.

The results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution because of several methodological limitations. First, relevant factors related to SA, such as pharmacotherapy, comorbidities, illness severity and the actual mood state of BD, were not reported in most studies, hence their moderating effects on SA could not be explored. Second, publication bias of the 1-year and current episode prevalence of SA could not be assessed as the number of studies was <10 (Wan et al., Reference Wan, Hu, Li, Jiang, Du, Feng, Wong and Li2013). In addition, the pooled current episode and 1-year SA prevalence estimates and the SA-moderating effects of the region and low-income countries were examined in a small number of studies, therefore the findings are only preliminary. Third, most studies were conducted in the Americas and Europe, making the generalisability of findings limited. Fourth, although subgroup analyses have been performed, heterogeneity could not be avoided as it is a common pitfall in the meta-analysis of epidemiological studies (Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Ganapathy, Marwaha, Large, Birchwood and Singh2013; Long et al., Reference Long, Huang, Liang, Liang, Chen, Xie, Jiang and Su2014; Rotenstein et al., Reference Rotenstein, Ramos, Torre, Segal, Peluso, Guille, Sen and Mata2016). The heterogeneity in the current meta-analysis was probably due to the systematic differences between included studies, such as diverse study aims and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Fifth, there may be recall bias in the assessment of SA. Finally, the number of studies that reported data on the current episode and 1-year prevalence was less than those that examined lifetime prevalence that could have influenced the results to an uncertain degree.

In conclusion, the meta-analysis found that the prevalence of SA in BD is higher than the figures reported in schizophrenia and in the general population. Given the major impacts of SA on BD, more mental health resources should be allocated and effective measures should be undertaken to reduce the risk of SA in this population. Identifying the risk factors of SA (e.g. rapid cycling type and female gender as found in this study) and the long-term use of mood stabilisers coupled with psycho-social interventions could reduce the risk of suicidal behaviour (Rihmer, Reference Rihmer2008), e.g. long-term treatment with lithium reduced SA by 10% and completed suicide by 20% (Benard et al., Reference Benard, Vaiva, Masson and Geoffroy2016).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000593.

Data

All the data supporting the findings of this meta-analysis have been provided in Tables, Figures and Supplemental Tables and Figures.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

The study was supported by the University of Macau (MYRG2015-00230-FHS; MYRG2016-00005-FHS), the National Key Research & Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC1307200), the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (No.ZYLX201607) and the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals' Ascent Plan (No. DFL20151801).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

N/A.