Introduction

In the last 20 years, companies have increasingly tried integrating sustainable practices to respond to current societal challenges. An excellent sample is Patagonia, an American outdoor clothing retailer, which, for instance, allows merchandise in good condition to be returned for new merchandise credits. The used merchandise is cleaned, repaired, and sold on its ‘Worn Wear’ website (Rattalino, Reference Rattalino2018). Interestingly, only a tiny portion of firms achieved declared environmental performance targets, and the data are even more striking for medium enterprises (MEs) (firms that have between 50 and 250 employees and, alternatively, a maximum of €50 million in revenues or a maximum of €43 million in balance sheet assets (European Commission, 2020)), which largely impact current economies (Eurostat, 2022; The World Bank, 2021). In fact, despite the potential positive outcomes that adopting sustainable practices (e.g., environmental accounting tools; Javed, Yusheng, Iqbal, Fareed, & Shahzad, Reference Javed, Yusheng, Iqbal, Fareed and Shahzad2022) bring for companies, MEs seem to show less commitment to incorporating these initiatives compared to larger corporations (e.g., Kucharska & Kowalczyk, Reference Kucharska and Kowalczyk2019; Shields & Shelleman, Reference Shields and Shelleman2015). In this regard, studies suggest that developing a sustainable performance management system (SPMS) – a set of ‘indicators that provides a corporation with the information needed to help in the short- and long-term management, controlling, planning, and performance of the economic, environmental, and social activities undertaken by it’ (Searcy, Reference Searcy2012, p. 240) – can help MEs identify cost-saving opportunities and achieve environmental stewardship goals (Jassem, Zakaria, & Che Azmi, Reference Jassem, Zakaria and Che Azmi2022). By generating sustainability-related information, SPMSs can influence managers’ decision-making processes and improve companies’ overall sustainable performance (Searcy, Reference Searcy2012).

Nevertheless, while some contributions have investigated the factors influencing the adoption of sustainable practices (e.g., Ghadge, Er Kara, Mogale, Choudhary, & Dani, Reference Ghadge, Er Kara, Mogale, Choudhary and Dani2021) and ‘conventional’ performance management systems (PMSs) (e.g., Hristov, Camilli, & Mechelli, Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022), there remains a need for further research into the barriers preventing the development of sustainable practices in MEs. Unlike larger companies, where decision-making processes often involve multiple layers of management, MEs typically have constrained decision-making authority vested in a limited number of managers or even a single manager (e.g., Kumar, Boesso, Favotto, & Menini, Reference Kumar, Boesso, Favotto and Menini2012). This leads to MEs heavily relying on the decision-making abilities of a limited number of managers, whose bounded rationality and cognitive biases – i.e., systematic flawed patterns of responses to problems (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1972) – play a crucial role in shaping the adoption of sustainability practices, such as SPMS (Abatecola, Caputo, & Cristofaro, Reference Abatecola, Caputo and Cristofaro2018; Engler, Abson, & von Wehrden, Reference Engler, Abson and von Wehrden2019; Lovallo, Cristofaro, & Flyvbjerg, Reference Lovallo, Cristofaro and Flyvbjerg2023). Hence, managers’ behavior, influenced by bounded rationality and cognitive biases, can undermine the development and effective implementation of the SPMS and, thus, overall commitment to sustainable practices.

Yet, despite some initial studies rooted in the behavioral decision theory (BDT) (e.g., Einhorn & Hogarth, Reference Einhorn and Hogarth1981) have investigated how (few) cognitive biases impact MEs’ processes (e.g., Ahmad, Shah, & Abbass, Reference Ahmad, Shah and Abbass2021; Nuijten, Benschop, Rijsenbilt, & Wilmink, Reference Nuijten, Benschop, Rijsenbilt and Wilmink2020), including sustainable-oriented ones (e.g., Bianchi & Testa, Reference Bianchi and Testa2022; Roxas & Lindsay, Reference Roxas and Lindsay2012), their results may not directly translate or apply to the study of SPMS. This is because SPMS implementation requires a systematic and integrated approach that involves selecting and integrating performance indicators, establishing goals and targets, allocating resources, and developing processes and practices to monitor and improve sustainable performance (Searcy, Reference Searcy2009). These actions require a deep understanding of the organization’s strategic priorities, long-term objectives, and stakeholder expectations to embrace sustainable practices and embed them into the organizational culture. This strategic commitment sets SPMS apart from other tactical decision-making, requiring a comprehensive transformation of the organization’s mindset, values, and practices, that require special attention.

From that, we focus on three research questions:

RQ1: What cognitive biases mainly hinder the development of a SPMS in MEs?

RQ2: How can ME managers reduce these cognitive biases?

RQ3: What are the related beneficial potential outcomes from de-biasing a SPMS development in MEs?

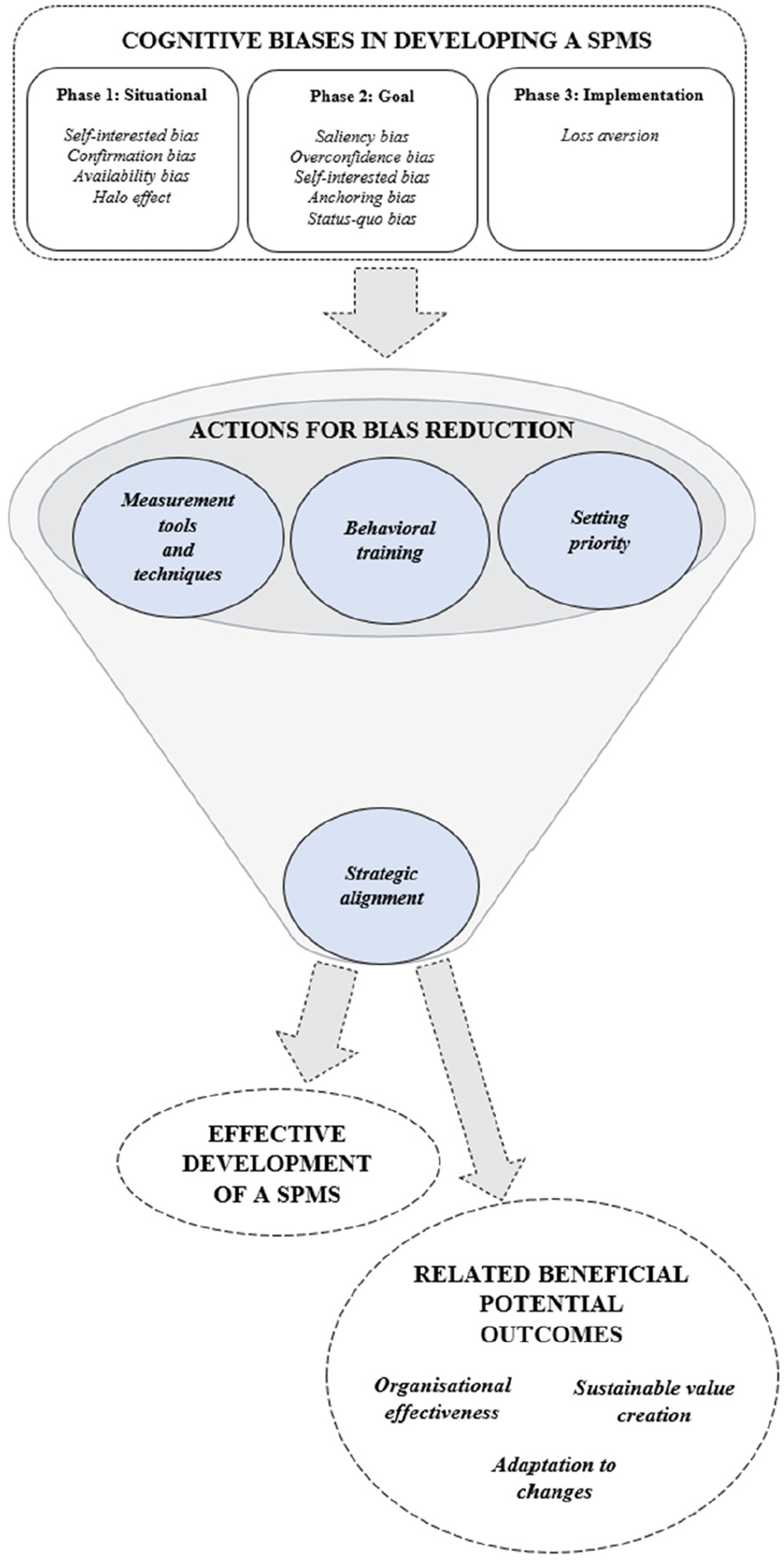

To answer these research questions, a mixed-method design has been adopted. A self-administered questionnaire composed of closed- and open-ended questions was completed by 277 Italian ME managers. In structuring the questionnaire, we considered the 12-question checklist to detect biases influencing decisions by Kahneman, Lovallo, and Sibony (Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011) and the conceptual framework for structuring the development of a SPMS by Searcy (Reference Searcy2009, Reference Searcy2012). The answers to closed- and open-ended questions were analyzed using, respectively, descriptive statistics and thematic analysis (TA) methods (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012). The findings were used to develop a ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ framework. Apart from the biases that respondents indirectly disclosed as mainly hindering SPMS development in MEs (saliency, availability, self-interest, and confirmation), the framework proposes some corrective actions (i.e., measurement tools and techniques, behavioral training, setting priorities, and strategic alignment) to manage and reduce the impact of cognitive biases for SPMS development, also reaching related beneficial potential outcomes (adaptation to changes, sustainable value creation, and organizational effectiveness).

This work makes some interesting theoretical and practical contributions. Results contribute to the advancement of BDT (e.g., Einhorn & Hogarth, Reference Einhorn and Hogarth1981) and behavioral strategy literature (e.g., Powell, Lovallo, & Fox, Reference Powell, Lovallo and Fox2011) by shedding light on the cognitive processes hindering the adoption of an SPMS and the related consequences in the strategic management of MEs. Specifically, the research identifies the specific cognitive biases that hinder the implementation of an SPMS in MEs. This empirical investigation provides valuable insights into the probability and magnitude of these biases, expanding our understanding of their impact on sustainability strategies in MEs. Additionally, the study introduces a theoretical framework, the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’, which connects the identified biases with corrective strategies for effective SPMS development. This framework offers a conceptual model that can serve as a basis for future research in BDT, behavioral strategy literature, and sustainability performance management. It opens avenues for further exploration of the interaction between cognitive biases and the implementation of sustainability strategies, not only in MEs but also in large companies.

From a practical viewpoint, the study suggests adopting corrective strategies to reduce the occurrence of cognitive biases. It emphasizes the importance of preventive measures for developing an SPMS in MEs. This includes implementing measurement tools and techniques, providing behavioral training, and priority setting to ensure unbiased decision-making. Managers are encouraged to involve key stakeholders in SPMS-related decision-making processes, fostering internal discussions and assessments to enhance the robustness and effectiveness of sustainability strategies. By following these recommendations, MEs can become more sustainability-oriented, meeting environmental challenges and fulfilling the requirements set by regulatory bodies.

Theoretical background

Sustainable performance management system in MEs

To achieve corporate sustainability, integrating corporate reporting and effectively communicating financial, environmental, social, and governance performance through a unified annual report is crucial. In fact, this approach demonstrates the organization’s commitment to sustainable practices, fosters trust, accountability, and informed decision-making among stakeholders, and drives positive social and environmental impact while ensuring financial stability and ethical governance (e.g., Dumay, Bernardi, Guthrie, & Demartini, Reference Dumay, Bernardi, Guthrie and Demartini2016; Global Reporting Initiative, 2021).

In this vein, developing specific measures for sustainable practices is pivotal to the composition of this single annual report. Although measuring is essential, Porter and Kramer (Reference Porter and Kramer2006, p. 80) stated that ‘any sustainability approach disconnected from business and strategy will obscure many of the greatest opportunities for companies to benefit society,’ i.e., indicators interconnected with the companies’ overall strategy (Ansari & Kant, Reference Ansari and Kant2017; Searcy, Reference Searcy2012). In this last regard, several authors debated the definitions and limits of a system for sustainability performance management (Searcy, Reference Searcy2012). The main advancement toward this direction has been penned by Searcy (Reference Searcy2012), who conceptually defined the SPMS, i.e., ‘a system of indicators that provides a corporation with the information needed to help in the short- and long-term management, controlling, planning, and performance of the economic, environmental, and social activities undertaken by the corporation’ (p. 240). Therefore, the SPMS is described as broader than a simple performance measurement system (Wood, Reference Wood2010). Indeed, the SPMS integrates drivers of sustainability from the first strategic phase of planning corporate objectives.

Searcy (Reference Searcy2009) repeatedly offered detailed and understandable guidelines for developing a SPMS. To develop a specific SPMS for an organization, using its internal structure and the needs of its external interlocutors, corporate decision makers are invited to focus (Searcy, Reference Searcy2009) on the (a) situational diagnostic, (b) goal diagnostic, and (c) implementation diagnostic of an SPMS. The situational diagnostic analyzes corporate and external contexts regarding strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. This phase concerns systematically surveying three areas: (a) sustainability in the corporate context to identify specific challenges and main stakeholders’ interests; (b) internal environment to understand sustainability policies, initiatives, and structures already in place; and (c) external environment to identify external stakeholders, their interests, and thus their potential effects on the SPMS. The goal diagnostic clarifies the enduring objectives to achieve through developing an SPMS. This phase systematically examines which are and are not the overall objectives of the SPMS and the linkages between new and existing targets. The implementation diagnostic focuses on future potential challenges and opportunities for the successful development of the SPMS from the beginning. This phase systematically reviews how information gathered through the SPMS will be used and what human, financial, technological, and informational resources are required to develop a strong SPMS.

According to existing literature, developing an SPMS is socially and economically desirable for organizations (Cardoni, Zanin, Corazza, & Paradisi, Reference Cardoni, Zanin, Corazza and Paradisi2020). The associated benefits are due to the management of a larger amount of data (Garengo, Biazzo, & Bititci, Reference Garengo, Biazzo and Bititci2005), allowing the organization to track processes granularly and connect managerial practices and sustainable outcomes in financial reports (Bahri, St-Pierre, & Sakka, Reference Bahri, St-Pierre and Sakka2017).

Regardless, MEs face greater obstacles in developing an SPMS than large companies. First, MEs have lower economic and organizational resources and competences than large companies. On this point, Neely, Gregory and Platts (Reference Neely, Gregory and Platts1995) pointed out that measurement is a luxury for MEs, concluding that the cost of measurement is an issue of great concern to their managers. Second, MEs have better resources and managerial competences and knowledge than small companies for developing an SPMS; this is mainly due to their greater systemic connections with other organizations and stakeholders, a penetrated market, established formal rules and processes, strategic forethought, an established managerial body that is separated from the governance body, and business knowledge (Hudson, Smart, & Bourne, Reference Hudson, Smart and Bourne2001; Siegel, Antony, Garza-Reyes, Cherrafi, & Lameijer, Reference Siegel, Antony, Garza-Reyes, Cherrafi and Lameijer2019).

However, ME managers may face challenges developing sustainable measurements (Isensee, Teuteberg, Griese, & Topi, Reference Isensee, Teuteberg, Griese and Topi2020). The above factors, though relevant, might be one of many determinants influencing the adoption of sustainable practices, such as SPMS, in MEs. Indeed, we posit that cognitive biases play a pivotal role in this context, affecting decision-making processes. We address this critical issue in the proposed study.

Bounded rationality and cognitive biases: A theoretical premise

BDT is an overarching framework characterizing how individuals breach rational norms in their decision-making processes (Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein, Reference Slovic, Fischhoff and Lichtenstein1977). Within this framework, research has centered around two areas where individuals depart from rational axioms in their decision behavior: bounded rationality and cognitive biases (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1972; Simon, Reference Simon1947).

According to Herbert Simon (Reference Simon1947), human beings’ abilities to act fully rationally (We adopt Gilboa and Schmeidler’s (Reference Gilboa and Schmeidler2001) definition of rationality where a decision is rational when ‘the decision maker is confronted with an analysis of the decisions involved, but with no other additional information, he/she does not regret her choices’ (pp. 17–18).) are insufficient due to (a) computational capacity, (b) impossibility of accessing all information, and (c) biological limits. In other words, individuals cannot accurately perceive, memorize, represent, and compare all the possible alternatives in complex decision-making processes, failing to find the optimal option and, in turn, looking just for a satisfying one. They are, in brief, bounded rational. This deviation from the rational behavior – postulated in classical economic models – is explained in dual-process theories (e.g., Stanovich & West, Reference Stanovich and West2000), which hypothesize the existence of two distinct mental processes in the human mind: one that operates automatically and another that works in a controlled fashion (Neys, Reference Neys2006). The Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman (Reference Kahneman2003, p. 698) deepened the understanding of such mechanisms by labeling them as System 1 and System 2: ‘The operations of System 1 are typically fast, automatic, effortless, associative, implicit (not available to introspection), and often emotionally charged’, while operations of System 2 are ‘slower, serial, effortful, more likely to be consciously monitored and deliberately controlled; they are also relatively flexible and potentially rule-governed’.

Due to the often-automatic activation of System 1, individuals implicitly tend to reduce complex decision-making tasks into simpler judgmental operations (Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, Reference Kahneman, Slovic and Tversky1982; Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1972; Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1973). This simplification occurs through the intervention of cognitive biases (or simply biases). One case is of a stereotype driving a criminal investigation. For example, regarding a theft in a shop, police may start to look for a suspect focusing disproportionately on minorities (i.e., representativeness bias) (The representativeness bias is the mistake of believing that two similar things or events are more closely correlated than they are.), clouding investigators’ judgment. They may draw upon their stereotypes of demographic groups that are most likely to commit that type of crime.

To avoid biases, organizations can collectively reflect on decisions using System 2 to prevent individuals’ System 1 mistakes (Kahneman, Lovallo, & Sibony, Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011). In this regard, Kahneman, Lovallo, and Sibony (Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011) developed a 12-question checklist to simplify the collective ‘evaluating party’ role in identifying biases from previous decision-making processes.

Cognitive biases and sustainability business practices

Over the last decade, the impact of biases on decisions and their significant interconnections have been investigated mainly in the business setting (e.g., Fan, Chen, Wu, & Fang, Reference Fan, Chen, Wu and Fang2015; Zhang & Cueto, Reference Zhang and Cueto2017). More recently, given the increased attention that sustainability issues are receiving worldwide, scholars also started to be interested in understanding the interplay between adopting sustainable business practices (i.e., corporate social responsibility) and biases (Engler, Abson, & von Wehrden, Reference Engler, Abson and von Wehrden2019).

Considering this latter stream, it also appears noteworthy to recall the contribution by Sauerwald and Su (Reference Sauerwald and Su2019), who demonstrated the negative impact of chief executive officers’ overconfidence – i.e., the tendency to be overbearing regarding the accuracy of their judgments (Lovallo & Kahneman, Reference Lovallo and Kahneman2003) – on firms’ corporate social responsibility decoupling (i.e., the gap between how firms communicate about and what they do in terms of corporate social responsibility). More recently, Park, Byun, and Choi (Reference Park, Byun and Choi2020) have found, in their US study, that overconfident CEOs seem to consider corporate social responsibility practices to have a low impact, consequently reducing long-term performance in publicly traded corporations in the US. Yet, the recent conceptual review of Engler, Abson, & von Wehrden (Reference Engler, Abson and von Wehrden2019) on the effects of cognitive biases in the general context of sustainability highlighted that both individual and group biases negatively influence the sustainable behavior of companies, in that the latter may outweigh those on the personal level and exacerbate the effects. However, it is also true that the power of the collective level can mitigate the manifestation of these biases (see also Kahneman, Lovallo, & Sibony, Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011).

However, despite the growing interest to include psychological factors in the investigation of sustainable practices (Engler, Abson, & von Wehrden, Reference Engler, Abson and von Wehrden2019), there is a paucity of contributions devoted to the analysis of the impact that cognitive biases have on sustainability practices and the SPMS in particular.

One example of a study addressing the role of biases in the PMS is by Hristov, Camilli, and Mechelli (Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022). These scholars studied 104 experienced professionals’ evaluations on the likelihood and impact of managers’ cognitive biases in PMS implementation. They found that (a) setting an outcome aligned with their interest (self-interested bias) and (b) minimizing/exaggerating the negative/positive impact of something based on their own emotions (affect bias) are the two most common biases in the PMS implementation. Yet, Hristov, Camilli, and Mechelli (Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022) also proposed a framework to consider and reduce the impact of biases in PMS implementation. Accordingly, we improved the results achieved by the authors by investigating the cognitive biases that hinder the development of an SPMS in MEs. We have contributed to the existing literature by adding knowledge on the research of the role of the cognitive biases in implementing a structured PMS and found the most prominent biases influencing SPMS development. We used the findings to develop a ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ framework with the aim of supporting decision-making processes of the sustainability professionals in developing a sustainable strategy for MEs.

Methodology

Research design

This work aims to detect the critical cognitive biases hindering the development of an SPMS in MEs and identify how to reduce them and spot the beneficial potential outcomes from de-biasing an SPMS development. We issued a self-administered questionnaire and exercised two processes as follows.

First, to detect the critical cognitive biases hindering ME’s SPMS development, we collected managers’ quantitative evaluations through closed-ended questions and analyzed the responses through descriptive statistics. Second, to identify how to de-bias an SPMS development and spot the related beneficial potential outcomes, we collected managers’ open-ended answers that were then analyzed through TA. This mixed-method research approach allowed us to deductively identify which critical biases hinder SPMS development in MEs from the quantitative investigation. At the same time, we inductively guided qualitative investigation to obtain the desired granular understanding of the de-biasing strategies for critical biases previously identified.

We considered this mixed-method research design (giving equal weight in importance to the quantitative–qualitative sequence; Bell, Bryman, & Harley, Reference Bell, Bryman and Harley2022) as the most fitting since, as postulated by Edmondson and McManus (Reference Edmondson and McManus2007, p. 1165), when an investigation intersects ‘separate bodies of literature’ – as for the case of biases and SPMSs – the combination of quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods (i.e., descriptive statistics and TA) successfully ‘generate greater understanding of the mechanisms’’ underlying results. The validity of this mixed-method approach, specifically based on descriptive statistics of closed-ended answers and TA of open-ended answers, has already favored its widespread use in management science (Molina-Azorin, Reference Molina-Azorin2012).

To implement the mixed-method research design and achieve the paper’s aim, we followed the data collection and analysis steps shown in Table 1. In particular, we (a) developed a self-administered questionnaire based on impactful biases identified by previous authoritative literature, (b) validated the elaborated self-administered questionnaire via a pilot test, (c) identified the sample of respondents, (d) collected and screened quantitative and qualitative data derived from the self-administered questionnaire, and (e) quantitatively and qualitatively investigated the data. On this last point, as Edmondson and McManus (Reference Edmondson and McManus2007, p. 1160) recommended for intermediate theory research, we analyzed the quantitative data that emerged from the structured questions through descriptive statistics, while we investigated the qualitative data collected by open questions through a TA.

Finally, given the results obtained from quantitative and qualitative analyses, a conceptual framework for de-biasing the development of an SPSM in MEs was elaborated.

Table 1. Data collection and data analysis steps

Questionnaire development

The data collection process started with developing a questionnaire for potential respondents. To avoid translation problems, participants were pre-warned when approached and, without exception, formally asked if they felt confident in completing the questionnaire in the English language (see also Chidlow, Plakoyiannaki, & Welch, Reference Chidlow, Plakoyiannaki and Welch2014). The questionnaire, structured into four sections (see online supplementary files), was delivered using Google Forms, allowing us to control the four sections accordingly. Further details are provided below:

(a) In the first section, we asked respondents to report their sociodemographic features regarding: (a) age, (b) gender, (c) job position, (d) years of experience in the controlling role, (e) industry, and (f) years of experience with SPMSs.

(b) For the second section, we adapted and developed the 12 questions of Kahneman, Lovallo, and Sibony (Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011) checklist, which focus on detecting the impact of occurring biases in a decision, based on Searcy’s (Reference Searcy2009, Reference Searcy2012) SPMS framework. We intertwined these two tools according to our consideration of the potential biases that could intervene during SPMS development (based on academic and professional knowledge). Therefore, we elaborated 22 statements oriented to identify the impact of occurring biases over the three diagnostic sections – situational, goal, and implementation – of the SPMS framework. Each statement elicits, therefore, a specific bias of Kahneman, Lovallo, and Sibony (Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011) checklist occurring in a phase of SPMS development. An example of this adaptation process may be observed by looking at the first three lines of Table 5 (situational diagnostic section). By interpreting sustainability in the corporate context, as described by Searcy’s (Reference Searcy2009, Reference Searcy2012) framework, we individuated potentially influencing biases, described by Kahneman, Lovallo, and Sibony (Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011) checklist, as availability bias, self-interested bias, and groupthink bias. In practice, as reported in the column ‘Effect’, in this phase, decision makers could choose the definition of sustainability based on a limited range of data/information (i.e., availability bias), and/or according to their personal interest (i.e., self-interested bias), and/or involving too large groups of stakeholders to avoid conflicts (i.e., groupthink bias).

Specifically, managers were asked to point out, based on the experiences collected during their career, how much the biasing event, substantiated by the statement, is likely to occur and its eventual harmfulness for SPMS development. For both probability and impact measurements, we used a 5-point Likert-type scale where the attributable values range from 1 (minimum probability and impact) to 5 (maximum likelihood and effect), considering a score ranging from 3 to 5 as a critical level.

(c) As part of the questionnaire process, respondents were preinformed about the aim of completing Section 2 and about the next two sections (3 and 4) of the questionnaire. After completing Section 1, the respondents were directed to watch a 3-minute-long preset interview video (Walton Family Foundation (2022) on Kahneman’s explanation of cognitive biases. By doing so, we ensured (a) that the respondents were aware of the concept of biases, (b) how we interpreted biases for this study, and (c) that they were ready to answer the following sections of the questionnaire. In Sections 3 and 4 of the questionnaire – inspired by Kahneman, Lovallo, and Sibony (Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011) and Searcy (Reference Searcy2009, Reference Searcy2012), we proposed, respectively, three open-ended questions directed at understanding the strategies respondents would embrace for reducing the cognitive biases they disclosed as ‘critical’ in Section 2 and two questions aimed at determining the related beneficial potential outcomes originating from de-biasing an SPMS development.

For validation, the elaborated questionnaire was administered to a convenient sample of (a) 10 ME managers who held managerial control roles for at least 5 years and had work experience with an SPMS and (b) three professors with academic expertise in decision-making (i.e., 1) and performance management (i.e., 2). Each manager/professor filled the questionnaire and then, individually, debated with us the appropriateness of each statement/question according to practical and literary points of view. Each statement/question was then refined according to the received feedback.

Sample selection

To generate the sample population, MEs were chosen using the AIDA (Analisi Informatizzata delle Aziende Italiane) database (An online database containing financial, personal, and commercial information on over 500,000 companies in Italy. All Italian companies registered at the Chambers of Commerce are present in the database.) to filter for those that (a) are active, (b) have their main headquarters located in Italy, (c) have between 50 and 250 employees and, alternatively, a maximum of €50 million in revenue or a maximum of €43 million in balance sheet assets (these are the criteria for defining an ME according to the European Commission and in line with Italian law), and (d) have available either human resources or administrative departments’ contact information (i.e., e-mail address). After filtering, the questionnaire was sent by email to 1,922 managers with a request for their participation.

The overall data collection process consisted of an initial mailing in March 2022, a follow-up email in May 2022, and a second mailing in July 2022, resulting in a final 17% response rate, i.e., 330 respondents. A test for nonresponse bias was conducted by comparing the responses received from the ‘first‐mailing’ respondents (221; 67%) with those received from the ‘second-mailing’ (76; 23%) and ‘third-mailing’ (33; 10%) respondents. A statistical comparison of these three datasets has revealed no significant differences in collected sociodemographic features. In addition, as part of an attempt to increase the response rate and ascertain reasons for nonresponse, 20 of the non‐respondents (randomly selected) were contacted by telephone. The three most widely cited reasons for not responding were ‘not enough time’ (52%), ‘completion of surveys contravened company policy’ (25%), and ‘company provider blocks external unrecognized email sender’ (10%). No factors cited for nonresponse suggested a nonresponse bias threat.

Self-administered questionnaires were scrutinized to eliminate those that were totally or partially invalid. Among them, 53 were discarded given their invalidity (i.e., partially uncompleted or unfitting with the manager’s experience and/or job position requirement), resulting in 277 valid questionnaires.

Table 2 reports the demographic records of the respondents concerning age, gender, experience, job position, and industry. As a result, the most frequent type of participant was male (59%; this disequilibrium is almost in line with average Italian managers’ distribution by gender; Statista, 2020), with 11–15 years’ experience in management control functions (56%) and occupying senior positions (63%) in the manufacturing industry (33%).

Table 2. Demographic data

Data analysis

Data collected through the self-administered questionnaire were analyzed as follows. Quantitative scores assigned by managers to statements presented in Section 2 of the questionnaire about the probability and impact of cognitive biases in SPMS development were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Concerning the open-ended questions statements provided to answer questions in Sections 3 and 4, they have been investigated through TA (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012). The goal was to identify (a) the de-biasing strategies to be adopted to reduce those biases that respondents have indirectly pointed out as critical in SPMS development (we analyzed answers from Section 3 of the questionnaire) and (b) the related beneficial potential outcomes affecting the whole organization due to proposed corrective actions on SPMS development (we analyzed answers from Section 4 of the questionnaire).

In general, TA displays data and information in an excellent, unambiguous way supporting scholars in defining the theoretical and practical links needed for a deeper comprehension of the mechanisms behind the topic under investigation (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998). Explicitly, TA is principally employed to acquire a nuanced understanding of spontaneous and sophisticated processes, as well as to envision ‘new constructs with few formal measures in an open-ended inquiry’ (Edmondson & McManus, Reference Edmondson and McManus2007, p. 1160) – such as the case of the key cognitive biases that hinder managers of MEs in implementing an SPMS, as well as the way through which these cognitive biases can be reduced.

We followed the six-phase protocol by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012) for the TA. In particular the following:

(a) Familiarizing ourselves with the data – We became fully familiar with data from the completed questionnaires to detect any initial analytic observation.

(b) Coding – Codes serve to identify a feature of the data – either semantic content or latent (we used the latent one) – that may appear to be interesting for the analyst as they indicate ‘the most basic segment, or element, of the raw data or information that can be assessed in a meaningful way regarding the phenomenon’ (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998, p. 63). All codes (present in answers of both Sections 3 and 4 of the questionnaire) have been retrieved inductively, since we did not have a predefined set of de-biasing strategies/benefits in mind (or taken from the literature) to be tested. This identification was based on research scientific knowledge and data interpretation (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012). Figure 1 shows an example of how we identified codes for answers to Section 3 of the questionnaire (de-biasing strategies). The total number of codes (22) that emerged from the answers to questions in Sections 3 and 4 was formed at the end of the overall review process. See Table 3 for the full list and definitions.

(c) Searching for themes – We retrieved themes inductively. Themes are shared meaning patterns underpinned by a central meaning-based concept that can be identified in a semantic or latent manner; we opted for the latent (Vaismoradi, Jones, Turunen, & Snelgrove, Reference Vaismoradi, Jones, Turunen and Snelgrove2016).

(d) Reviewing themes – We reflected on whether conceived themes can depict a convincing and compelling story about the collected data. We concluded reviewing codes and themes when the qualitative information provided by the respondents reached data saturation at the 165th completed self-administered questionnaire. This may be considered as quite late due to the newness regarding the inter-relation of investigated topics.

(e) Defining and naming themes – We conducted and wrote a detailed analysis of each theme by identifying its core meaning, in light of the research question(s) and, consequently, labeling it accordingly. We concluded this step with a list of seven themes: four concerning de-biasing strategies (behavioral training, setting priority, measurement tools and techniques, and strategic alignment) and three about the related beneficial potential outcomes (adaptation to changes, sustainable value creation, and organizational effectiveness). See Table 4.

(f) Producing the report – We weaved together the analytic narrative and the insights grasped from the collected information to inform readers of a coherent and persuasive story about the data and contextualized it in relation to the existing literature and the research question(s). This last step permitted highlighting the biases hindering managers from implementing an SPMS and strategies to overcome them, considering the related beneficial potential outcomes, and expediting the construction of an explanatory framework comprising codes and themes.

Figure 1. Identification of codes.

Table 3. Codes and their definitions

Table 4. Themes and their definitions

It is worth noting that each author analyzed the open-ended questions individually and compared their coding. On average, the inter-rater reliability between them for codes and themes was high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). However, the authors expanded the analysis when disagreeing in order to reach a shared vision of each sentence’s meaning and related theme.

Findings

Main biases hindering the development of an SPMS in MEs

Results obtained from the participants’ responses to the closed-ended questions (Section 2 of the questionnaire), unitedly with a description of biases and their effect on the development of the SPMS, are reported in Table 5. The statistical results provided helped to answer RQ1.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics

Precisely, all presented scores ranged between 2.69 and 3.77, with a maximum standard deviation of 1.22. Notably, the mean of scores attributed to the impact of biases (3.32) was higher than the probability that they will happen (3.10), which was likely because of reasonable concerns about such events that need to be reduced. Results were then analyzed according to the SPMS phase.

During the situational diagnostic phase, managers seemed to interpret the concept of sustainability based on a limited range of data and looked for information that fits better with their own beliefs or personal interests. In fact, the most likely distortions identified were confirmation bias (3.31), availability bias (3.46), self-interested bias (3.26), and halo effect bias (3.20). Therefore, the managers analyzed the general environment as being affected by distortions that replace their supposed knowledge about sustainability and sustainable practices. During the goal diagnostic phase, respondents disclosed an average of 3.37 and 3.71 for overconfidence and saliency biases, respectively. In this regard, it could be assumed that a link between these two biases exists, since the former may affect the latter during the creation of the overall firm’s goal and objectives by pushing managers not to be immediately in favor of developing an SPMS.

Moreover, anchoring (3.09) and status quo (3.17) biases jointly bind the organizations to old objectives and non-updated systems. Only one critical value (loss aversion, 3.34) was reported in the implementation diagnostic phase. In this phase, loss aversion bias clearly highlighted the managerial regret in Italian MEs to adopt innovative tools as the costs were known, while gains were yet to be discovered.

Reducing cognitive biases hindering the development of an SPMS in MEs

Codes are quantified according to the number of appearances across the self-administered questionnaires. As Table 6 shows, the frequency of themes is calculated according to the sum of codes’ frequencies pointing to them. The codes with the highest frequency rate, considering their appearances among all themes, are as follows: ‘social integration’ (N = 626, 14%), ‘KPIs’ (N = 496, 11%), and ‘sharing goals’ (N = 353, 8%). Among the identified 22 codes, 12 are connected with the de-biasing strategies (Section 3 of the questionnaire), while 10 are about the related beneficial potential outcomes in de-biasing an SPMS (Section 4 of the questionnaire).

Table 6. Number and frequency of the codes and themes extrapolated from the open-ended questions

The 12 codes regarding de-biasing strategies, answering RQ2, are grouped into four main distinct themes (see Table 4 for more quotes). They are as follows:

Behavioral training consists of four codes: ‘learning by experience’, ‘coaching’, ‘challenging the status quo’, and ‘controlling senior discretion’. This theme deals with the reduction of the impact of biases during the development of an SPMS by the mean of a structured set of activities, even with the assistance of external experts, specifically designed to boost the familiarization with specific soft skills (e.g., bias recognition) (Lovallo & Sibony, Reference Lovallo and Sibony2010). In this vein, Respondent no. 113 declares: ‘I’m endorsing policies to incentivize a fruitful exchange of knowledge among co-workers to let them be fully aware of why we had to leave our old standards and adopt an SPMS [status quo] to be able to put this company in line with the procedures suggested by the EU’.

Setting priority consists of three codes: ‘resource leveraging’, ‘KPIs’, and ‘sharing goals’. This theme deals with the correct delineation of present and future priorities that can play an essential role in the effective and efficient development of an SPMS. By aligning sustainability objectives and internal processes (Chenhall, Reference Chenhall2005), an SPMS may lead to overall improved performance (Verbeeten & Boons, Reference Verbeeten and Boons2009). In this regard, Respondent no. 129 states: ‘I implemented a bunch of sustainable metrics, which, nonetheless, had to be partially changed given that a group of stakeholders rebuked me for having not taken into consideration some of their needs [self-interest]. Therefore, I was forced to engage in a discussion and align my strategy with their specific requests’.

Measurement tools and techniques consists of four codes: ‘benchmarking’, ‘data-driven analysis’, ‘data sharing’, and ‘KPIs’. This theme deals with the importance of embracing the right set of tools and techniques for setting policies and actions during the development of an SPMS (Kreilkamp, Schmidt, & Wöhrmann, Reference Kreilkamp, Schmidt and Wöhrmann2020). Precisely, given that managers’ perception about the status of their sustainable organizational performances could be biased, it is important not only to have certain data available but also to share them for collecting feedback – reducing the possibility of falling victim to cognitive distortions. In this light, Respondent no. 23 affirms: ‘We bought software for data analysis. Thanks to it, we can collect, analyze, and share real-time data, which is essential to take full advantage of the value the SPMS brings to our company and not just supposing it [overconfidence]’.

Strategic alignment consists of seven codes: ‘top-down engagement’, ‘cross-functional communication’, ‘data sharing’, ‘KPIs’, ‘coaching’, ‘sharing goals’, and ‘social integration’. This theme appears to be one of the most critical that emerged from the analysis, given that the effective development of an SPMS goes through the broadest consensus possible among stakeholders – in terms of mindset, priorities, and managerial approaches. Without this agreement, it would be tough to effectively plan and define the translation of the SPMS for the business (Walter et al., Reference Walter, Kellermanns, Floyd, Veiga and Matherne2013). In this regard, Respondent no. 92 discloses: ‘I perceived sustainability as a lever to face the market crisis. To effectively communicate this vision throughout the company, I asked for individual interviews and created focus groups to share thoughts about it [groupthink]; this helped me and my collaborators align the entire community to the firm’s strategic vision and collect feedback to improve our SPMS’.

Related beneficial potential outcomes from de-biasing an SPMS development in MEs

The 10 codes linked to the related beneficial potential outcomes of adopting an SPMS, answering RQ3, are grouped into three main distinct themes (see Table 4 for more quotes):

Adaptation to change consists of three codes: ‘strategic flexibility’, ‘social integration’, and ‘cultural change’. This theme brings together the codes linked to the ability of the SPMS to let firms adapt to the ever-changing market dynamics. However, managers affirm that this function is not exempted from being subject to the pressure of cognitive bias by those who are called not only to implement the SPMS but also to use the resulting data for strategic purposes (Kim & Kankanhalli, Reference Kim and Kankanhalli2009). In this vein, Respondent no. 30 declares: ‘To implement the SPMS has required changing the mindset and become more flexible. […] I organized small teams assigned to specific aspects through which we can quickly respond and adjust the issues detected by the sustainable metrics’.

Sustainable value creation consists of four codes: ‘risk reduction’, ‘economic growth’, ‘environmental efficiency’, and ‘social integration’. This theme deals with the ability of a well-developed SPMS to produce value added by helping firms to align their goods/services to customers’ social needs (i.e., when purchasing, a growing share of customers take into consideration issues such as ethical consumption, lifestyle choices, and social responsibility; Sawicka & Marcinkowska, Reference Sawicka and Marcinkowska2022), triggering a virtuous course of action (Porter & Kramer, Reference Porter and Kramer2006). Respondent no. 270 affirms: ‘Adopting an SPMS allowed us to better integrate the local community concern about environmental sustainability into our strategy. On the one hand, this has enhanced our environmental efficiency – resulting in higher savings for the firm – and, on the other hand, increased our reputation’.

Organizational effectiveness consists of four codes: ‘intellectual capital’, ‘cohesion’, ‘transparency’, and ‘productivity’, all related to the concept of organizational effectiveness linked to the effective development of the SPMS. In fact, when sustainable goals drive a firm, they can easily promote good management practices such as a better awareness of the long-term impacts of business decisions, building management capacity, and improving operational efficiency, quality, and profitability (Schoen, Reference Schoen, Walker, Krosinsky, Hasan and Kibsey2019). In this light, Respondent no. 164 discloses: ‘A well-developed SPMS required the management team to spend the proper amount of time and resources in explaining the “how” and “why,” as well as in properly training people to manage the information resulting from the SPMS. After this, everything became smoother and the firm started to benefit from such a tool’.

Discussion and theoretical framework

MEs are considered as more prepared to develop sustainable measures (Zharfpeykan & Akroyd, Reference Zharfpeykan and Akroyd2022) due to their greater economic and managerial possibilities than small enterprises (Hudson, Smart, & Bourne, Reference Hudson, Smart and Bourne2001). Despite such possibilities to develop and adopt sustainable measures – essential for facilitating the long-term growth of every business organization – from recent analyses, only a small fraction of MEs is doing so (Generali, 2021). Stemming from the insights advanced by previous scholars on ME managers (e.g., Korteling, Brouwer, & Toet, Reference Korteling, Brouwer and Toet2018), it could be inferred that such a low rate could be the result of ME managers’ cognitive mechanisms given that their reasoning is automatically reflected in firms’ behaviors (Engler, Abson, & von Wehrden, Reference Engler, Abson and von Wehrden2019).

However, BDT and sustainability literature have not been convincingly integrated with the scope of studying how sustainable practices (e.g., the development of an SPMS) take place (or not) in MEs. Therefore, this article has aimed to fill the gap by answering three distinct, but interrelated, research questions: What cognitive biases mainly hinder the development of an SPMS in MEs? How can ME managers reduce these cognitive biases? What are the related beneficial potential outcomes from de-biasing an SPMS development in MEs?

In this vein, via the quantitative part of the study, it is possible to disclose the most frequent and influential biases occurring across the phases concerning the development of an SPMS in Italian MEs (RQ1). Specifically, it appears that during the first phase (i.e., situational diagnostic), managers seem to interpret the concept of sustainability based on a limited range of data and look for information that better fits their own beliefs or personal interests. During the second phase (i.e., goal diagnostic), respondents affirm the existence of biases affecting the creation of the overall firm’s goal and objectives by pushing managers not to be immediately in favor of developing the SPMS. For the last phase (i.e., implementation diagnostic), respondents report only one critical value that is linked to the loss aversion bias.

Hence, given the type of biases that harm ME managers – and since from the dual-process theory (e.g., Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003) we know that they lay in the System 1 of the human mind, the need clearly emerges for ME managers to have an innovative tool available to counteract such cognitive distortions. Therefore, the present study introduces a theoretical framework called the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ (see Fig. 2) to contextually synthetize cognitive biases related to the SPMS and address such distortions toward outcomes of a de-biased SPMS. The theoretical framework is essentially based on three main parts: (a) the association between managers’ most critical (in terms of impact and recurrence) cognitive biases affecting SPMS development; (b) the corrective actions suggested to reduce such biases during SPMS development, and (c) the related beneficial potential outcomes on the whole organization due to integration of these corrective actions to reduce the negative impact of these biases on SPMS development – apart from an effective development of the SPMS (primary beneficial outcomes). These three parts, graphically and logically connected through a top-down flow (i.e., from the critical cognitive biases to the outcomes of the actions proposed), are extensively described in the following subsections.

Figure 2. Sustainable performance measurement system de-biasing funnel for MEs.

Association between managers’ cognitive biases and the SPMS’s development phases

The first part links decision makers’ cognitive biases to each phase of the SPMS. The three phases of the SPMS’s development, as per Searcy (Reference Searcy2009), are the first essential part of the framework for two main reasons. First, they report the grounds on which cognitive biases are revealed, thus allowing us to understand when and where decision makers deviate from rational choice (Hammond, Keeney, & Raiffa, Reference Hammond, Keeney and Raiffa1998). Second, the three phases differentiate negative effects on the SPMS and, consequently, different kinds of corrective actions according to the specific situation. On the other hand, also depicted are the critical biases (those with an average probability of happening scoring more than 3) that affect the SPMS in each specific phase.

The situational stage of the SPMS hosts a relevant number of critical biases, likely because it is the first phase. It, thus, requests updated knowledge on sustainable development issues (Searcy, Reference Searcy2012), which is not popular with company managers (Isensee et al., Reference Isensee, Teuteberg, Griese and Topi2020). Indeed, specific biases, such as availability and confirmation, concern restricted collection and distorted interpretation of data about sustainability and its value drivers. Like Dube‐Rioux and Russo (Reference Dube‐Rioux and Russo1988), we signal underestimation of sustainable value drivers as possible consequences of availability and managerial confirmation biases based on the few pieces of information at our disposal.

The second phase regards the goals of the SPMS; hence, managers’ interests and behaviors influence the strategic address to take. Saliency and self-interested biases are already recognized as seriously impacting the development of the PMS (Hristov, Camilli, & Mechelli, Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022). Thus, they definitively represent critical distortions leading to personally influenced objectives over those collective ones (Kahneman, Lovallo, & Sibony, Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011).

Ultimately, the implementation phase is only hindered by decision makers’ loss aversion. The latter could definitively reflect the fear of innovative tools (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Chen, Wu and Fang2015), such as an SPMS, during the realization phase as costs appear transparent, while returns, economic/noneconomic, still appear obscure. In this direction, many studies already confirm the managerial resistance to chase potential gains that are derivable from sustainable actions unless these are prioritized by critical stakeholders (Esposito De Falco, Scandurra, & Thomas, Reference Esposito De Falco, Scandurra and Thomas2021).

Strategic alignment through actions for bias reduction

Stemming from the answers reported from Section 3 of the questionnaire, the second part of the framework proposes a bundle of specific actions (namely, measurement tools and techniques, behavioral training, setting priority, and strategic alignment) that – if fully integrated within the corporate strategy architecture – may reduce the occurrence and severity (RQ2) of those critical biases indirectly revealed by managers. Specifically, in the framework illustrated in Fig. 2, these actions are circled and explained as follows.

First, the degree of managers’ cognitive biases related to the SPMS can be analytically assessed by a system of measurement techniques, specifically made up of data collected, analyzed, and shared with the whole organization until they formulate KPIs (Hristov, Camilli, & Mechelli, Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022), which could be easily engaged in the benchmarking process.

Behavioral training, to directly reduce cognitive distortions influencing decisions, is also convincingly proposed by the managers themselves. Managers should become accustomed to having limited decisional discretion. In this view, professional coaching activity can make decision makers realize the existence of behavioral factors that negatively influence their choices, thus accepting such limitations. Moreover, a mind that challenges the status quo continuously improves the effectiveness of managerial choices in the long term (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988); a self-influenced mechanism of learning by experience is proposed to encourage all members to be engaged in propositions of new ideas, methods, and activities.

In order not to let managers’ biases drive the organization toward heavily unbalanced objectives, a crucial role is played in setting priority. In this vein, sharing goals with internal and external stakeholders helps to balance corporate goals by exploiting a kind of democratic mechanism (Kahneman, Lovallo, & Sibony, Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011); the use of KPIs can turn company objectives into measurable ones, thus facilitating the objectivity of the weighting process and leveraging resources push the organization to look for new targets without overweighting current ones.

Furthermore, to properly reduce the critical cognitive biases associated with the SPMS’s development, the alignment between the behavioral approach, made up of actions previously suggested, and corporate strategy is require to maximize the combined results of actions. The strategic alignment is reported in the tightest part of the funnel, where all actions must flow. Indeed, all corrective measures must be understood and addressed as the current corporate strategy (Schwenk, Reference Schwenk1995).

Nevertheless, activities may be customized and aligned according to the specific needs of the firm and its specific environment. For instance, measuring decision makers’ cognitive biases involves benchmarks, which are selected according to target company characteristics such as dimension and functions. Similarly, firms’ behavioral training is shaped by specific biases of managers, thus addressing the most critical aspects, rather than all behavioral issues indiscriminately. Even though resources should be exploited differently across points revealed, measurement techniques indicate the severity of cognitive distortions to address.

Finally, to enforce accounting tools for achieving a higher number of sustainable results (Javed et al., Reference Javed, Yusheng, Iqbal, Fareed and Shahzad2022), some adjusted previous managerial tools (Figge, Hahn, Schaltegger, & Wagner, Reference Figge, Hahn, Schaltegger and Wagner2002) and many proposed new environmental indicators are suggested (Herva, Franco, Carrasco, & Roca, Reference Herva, Franco, Carrasco and Roca2011). Instead, the actions proposed above head toward de-biasing the development of the SPMS through a behavioral approach; thus, our theoretical framework, the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’, definitively represents a novel tactic for the final aim of creating corporate value sustainably.

The outcomes produced by corrective actions on an SPMS development

The third block, at the bottom of the framework, is made up of two elements resulting from the adoption of the corrective actions proposed: (a) the effective development of the SPMS (main primary beneficial outcomes) and (b) the positive-related potential effects on the whole organization (RQ3).

Specifically, thanks to the suggested corrective actions, MEs’ managers can prevent managers from falling victim to what our respondents indicated as the most critical biases during the SPMS development that, indeed, may lead to (a) prioritizing and overemphasizing certain information or metrics over others (saliency bias), (b) rely only on easily accessible information, which may not accurately reflect the full extent of the enterprise’s reality (availability bias), (c) focus on information that supports their personal interests (self-interest bias), and (d) seek out only information that confirms their existing beliefs and assumptions, leading to biased and potentially inaccurate assessments (confirmation bias). In summary, through the corrective actions we propose, ME managers can effectively develop an SPMS to achieve more accurate and objective measurements of sustainability performance as well as enhance their credibility and transparency.

Complementary to these outcomes, the proposed corrective actions allow MEs to also achieve other positive-related potential benefits. First, the systematic implementation of measurement techniques and behavioral training activity to constantly reduce the status quo mentality convincingly generate strategic and cultural flexibility to adapt to the changing external context (Hristov, Camilli, & Mechelli, Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022). Second, behavioral training directly enriches the intellectual capital of the members as well as their motivation for outstanding and innovative work (Schaltegger & Wagner, Reference Schaltegger, Wagner, Schaltegger, Bennett, Burritt, Bennett and Burritt2006). Together with goal sharing, behavioral training makes the decision-making process weightier and more transparent for the whole stakeholder audience. Such positive orientation generates a cohesive business environment, which facilitates other organizations’ resource procurement process and, thus, its productivity. Finally, since the primary goal of the SPMS is to create sustainable organizational value (Searcy, Reference Searcy2012), the same goal motivates corrective actions to reduce cognitive biases hindering the SPMS itself. The coordination between behavioral training and priority setting leads to a fully conscious prioritization of activities, still aimed at improving business performances, but regarding sustainability issues (Engler, Abson, & von Wehrden, Reference Engler, Abson and von Wehrden2019). Since introducing this innovative framework directly uncovers behavioral issues to obtain a higher number of sustainable outputs, the generality of business actors may appreciate this serious effort in transparency for altruistic purposes. Therefore, the whole company’s performance can be boosted by stakeholders’ engagement and positive perceptions (Loureiro, Romero, & Bilro, Reference Loureiro, Romero and Bilro2020; Rodriguez‐Melo & Mansouri, Reference Rodriguez‐Melo and Mansouri2011). As a result, if the corrective actions proposed are systematically applied, the organization will implement a de-biased SPMS driving toward the creation of sustainable value for, and with, internal and external stakeholders.

Implications

Theoretical and practical implications

This research advances the theoretical framework of SPMS by delving into the previously unexplored territory of cognitive biases and their influence on SPMS development within MEs. Doing so enriches our understanding of the complexities and intricacies of implementing MEs’ sustainability practices. Our work starts filling a critical gap in the literature, i.e., why only a few MEs achieve declared environmental performance (Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Corbo and Caputo2021). We advance that not reaching declared environmental performance by MEs goes beyond the lack of resources and knowledge compared to larger companies. In particular, we affirm that this phenomenon is attributable to cognitive biases that can deviate MEs managers’ decision-making processes regarding sustainable practices.

Through an empirical investigation, we have identified the existence and degree of the specific cognitive biases impacting the various phases of SPMS development (RQ1) (Ansari & Kant, Reference Ansari and Kant2017; Searcy, Reference Searcy2009, Reference Searcy2012). Understanding the impact of cognitive biases over different stages of SPMS development enriches the theoretical understanding of decision-making processes concerning SPMS development because underlining where MEs managers’ decision-making process deviates. Consequently, we innovatively introduce the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ that connects the detected biases to potential corrective strategies and the resulting outputs (RQ2). By doing so, our theoretical model provides some solutions for successful SPMS development and implementation, making our research theoretically significant and practically valuable. Moreover, our research offers insights into the potential benefits of integrating these corrective measures for SPMS development and implementation (RQ3), moving the theoretical discourse on de-biasing SPMS from an operational level to a more strategic one.

The proposed framework theoretically supports the ‘outside view’ by Kahneman & Tversky (Reference Kahneman and Tversky1996 p. 588) within BDT and behavioral strategy literature (Lovallo, Cristofaro, & Flyvbjerg, Reference Lovallo, Cristofaro and Flyvbjerg2023). Thus, it encourages SPMS decision-making for MEs managers based on collective experiences and data from similar situations rather than relying on an individual’s intuition or unique circumstances. In particular, in developing an effective and efficient SPMS, MEs managers can rely on the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ to the detriment of those instinctive mind mechanisms of System 1 (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Doing so, in brief, increases the rationality of the managerial decision-making process (Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2013; Lovallo, Clarke, & Camerer, Reference Lovallo, Clarke and Camerer2012).

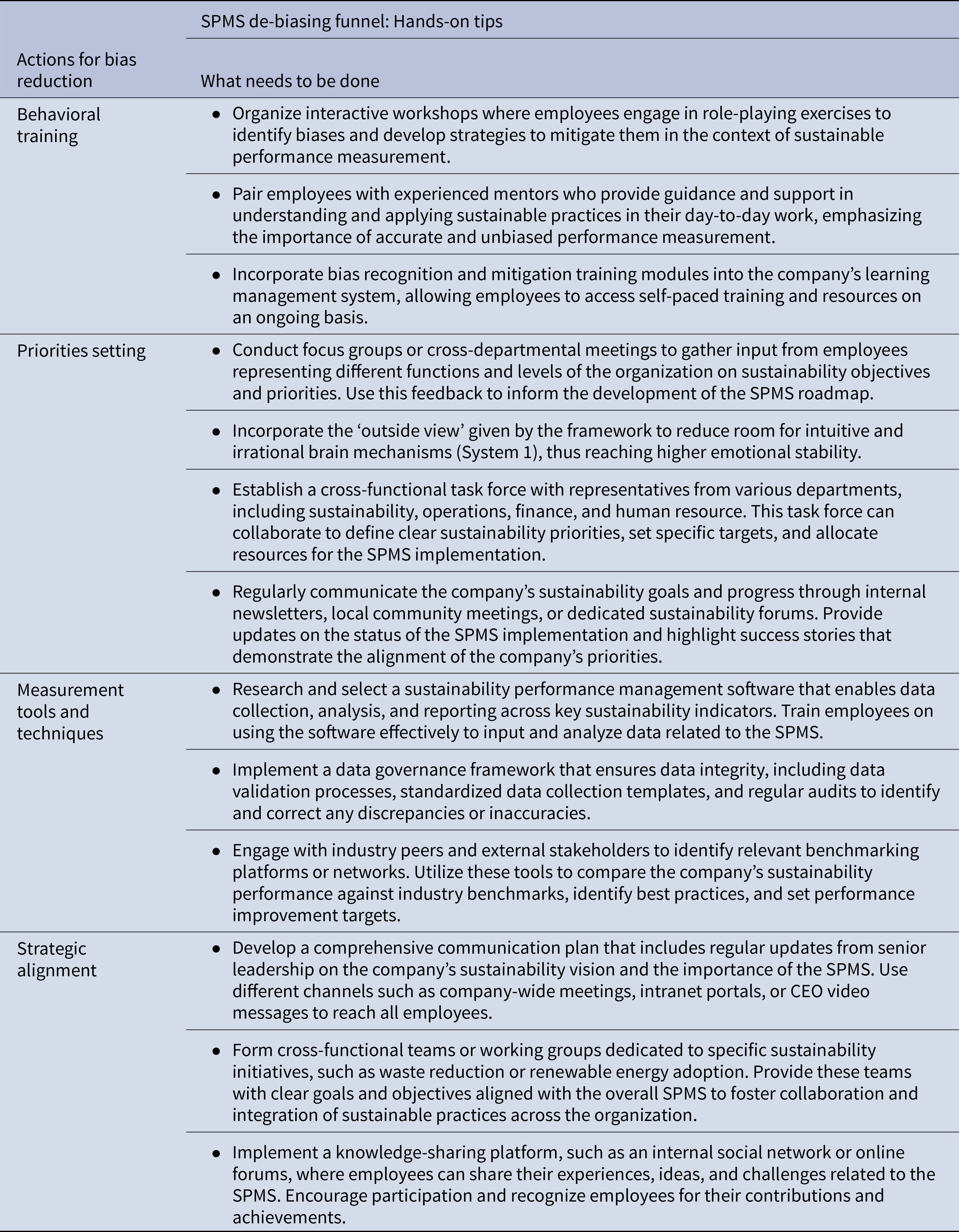

In terms of practical implications, the proposed framework suggests a set of viable corrective actions (i.e., behavioral training, setting priorities, measurement tools and techniques, and strategic alignment) for MEs’ managers to tentatively reduce the impact of their cognitive biases, while generating potential benefits (i.e., organizational effectiveness, sustainable value creation, and adaptation to change – in addition to the efficient and effective development and implementation of SPMS). A de-biased SPMS will unquestionably allow MEs to create value for their stakeholders and address current societal challenges. Thus, de-biasing the SPMS implementation and development is not merely about overcoming cognitive biases, it is about unlocking the organization’s potential to create lasting, sustainable value.

Here, we point out how MEs managers can implement the corrective actions of the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ (see Table 7).

Table 7. Practical suggestions to effectively and efficiently benefit from the ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ framework

For instance, strategic alignment is the organizations’ first critical action to foster a de-biased SPMS environment. This can be developed via a comprehensive communication plan. This plan can be implemented through regular meetings and intranet portals to share information across the organization. The communication plan should clearly articulate the senior leadership’s sustainability vision and underscore the importance of the SPMS to the organization’s overall strategic goals. By effectively communicating this vision, organizations can ensure that all team members understand the importance of sustainability and are aligned in their efforts to achieve the organization’s strategic objectives. Concerning behavioral training, this can be effectively imparted through interactive workshops that provide a hands-on experience on SPMS development and implementation, its benefits, and challenges. Additionally, mentorship programs can also be used to enhance behavioral training. These programs typically pair less experienced employees with senior colleagues who can guide them and provide personalized advice, thereby accelerating their professional growth and development. Furthermore, firms can enhance their learning management systems by incorporating modules specifically designed to recognize and mitigate biases. Such modules can help employees recognize their own unconscious biases, understand the impact of these biases on their decision-making, and learn strategies to mitigate them, thereby promoting a more diverse and inclusive work environment. Setting priorities within the organization is another critical aspect. This can be achieved by gathering valuable insights from employees through focus groups and cross-departmental meetings. Regular communication with key stakeholders is also essential as it ensures that everyone is on the same page and working toward the same goals. In terms of developing an SPMS, organizations should embrace the right set of tools and techniques for setting policies and actions. One effective approach is through a data governance framework, which ensures data integrity and facilitates the reliable analysis of performance metrics.

Limitations of the study and future research

This study is not exempted from limitations. Among them, it is noteworthy to recall that (a) the respondents were all managers of Italian-based enterprises; maybe there is a cultural factor of managers within the decision-making process that drives different biases, rather than managers in other cultures, (b) the authors focused their attention only on MEs – hence, we did not analyze larger more extensive and more structured environments where managers’ decisions are questioned more, (c) respondents who sometimes answered by speaking about their own experience could have fallen into a self-serving bias while completing the self-administered questionnaire, and (d) we did not ask respondents about the negative aspects related to the development of a de-biased SPMS (e.g., it may be time-costly).

Furthermore, similarly to Bedford, Bisbe, and Sweeney (Reference Bedford, Bisbe and Sweeney2019) and Hristov, Camilli, & Mechelli (Reference Hristov, Camilli and Mechelli2022), we epistemologically followed Kahneman’s (Reference Kahneman2011) traditional (and maybe more broadly accepted) point of view (e.g., Borchardt, Kamzabek, & Lovallo, Reference Borchardt, Kamzabek and Lovallo2022; Camerer & Lovallo, Reference Camerer and Lovallo1999; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003), acknowledging cognitive biases as always negative deviations from the rational decision-making pattern that should be avoided and mitigated through specific policies (see also Hammond, Keeney, & Raiffa, Reference Hammond, Keeney and Raiffa1998; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011; Kahneman, Lovallo, & Sibony, Reference Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony2011; Russo & Schoemaker, Reference Russo and Schoemaker1990). Nevertheless, we recognize the existence of a Gigerenzerian standpoint (e.g., Gigerenzer & Todd, Reference Gigerenzer and Todd1999; Zhang, van der Bij, & Song, Reference Zhang, van der Bij and Song2020), which views biases as usually hurting decision makers’ choices, but that can also sometimes lead to better decisions than analytical decision tools (e.g., statistical inference). Thus, we encourage researchers to adopt this latter perspective in describing how and under what circumstances biases may positively contribute to the ME managers’ development of SPMSs.

In addition to these limitations – which may represent a fertile groundwork for future studies – we highly suggest scholars adopt a holistic approach to investigating if the peculiar features and resources characterizing MEs enhance, or reduce, the propensity of their management to be subjected to cognitive distortions while developing an SPMS, compared with other kinds of firms (i.e., small- and large-sized enterprises). Organizational culture, strategic priorities, stakeholder expectations, and external pressures also play significant roles. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the complexities involved in SPMS implementation should include other relevant contextual elements.

Conclusions

This article contributes to BDT and behavioral strategy literature by using knowledge from the realm of psychology to shed light on the adoption of sustainable practices in MEs – which plays a significant impact on the global economy (The World Bank, 2021). Particularly, since the decision-making authority in MEs is typically constrained to a limited number of managers or even a single manager (e.g., Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Boesso, Favotto and Menini2012), it has been hypothesized that the adoption of tools such as the SPMS is subject to the bounded rationality and cognitive biases of these key decision makers. Results help to identify the existence and degree of the specific cognitive biases impacting the various phases of SPMS and to develop a ‘SPMS de-biasing funnel’ that connects the detected biases to potential corrective strategies and the resulting outputs. Finally, we shed light on the potential benefits of integrating these corrective measures for SPMS development and implementation, moving the theoretical discourse on de-biasing SPMS from an operational level to a strategic one. By doing so, this article establishes a solid groundwork for integrating sustainability at the core of MEs’ business operations: in fact, it paves the way for ME managers to embrace sustainability as a transformative force, reshaping mindsets, practices, and overall performance. In this vein, we hope to inspire further research endeavors and catalyze meaningful actions toward a sustainable future for society at large.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2023.55.