Introduction

Insects maintain homeostasis via integrated physiological systems with a division of labour among tissues (Klowden Reference Klowden2013). Thus, most physiological processes should be explored at the tissue level; for example, the midgut is usually the focus of digestion and absorption studies (Caroci and Noriega Reference Caroci and Noriega2003; Jagadeshwaran et al. Reference Jagadeshwaran, Onken, Hardy, Moffett and Moffett2010), while the Malpighian tubules are normally responsible for excretion (Dow et al. Reference Dow, Davies and Sozen1998). However, many transcriptomic studies analyse homogenised whole insects (e.g., Teets et al. Reference Teets, Peyton, Ragland, Colinet, Renault, Hahn and Denlinger2012; Poupardin et al. Reference Poupardin, Schottner, Korbelova, Provaznik, Dolezel and Pavlinic2015; MacMillan et al. Reference MacMillan, Knee, Dennis, Udaka, Marshall, Merritt and Sinclair2016; Torson et al. Reference Torson, Yocum, Rinehart, Nash, Kvidera and Bowsher2017; Koniger and Grath Reference Koniger and Grath2018), and thus do not capture tissue-specific processes, which may be important. For example, upregulated sodium pump expression in the Malpighian tubules would likely reduce primary urine production, while a similar upregulation in the hindgut would likely enhance water reabsorption to the haemolymph. The physiological implications of these two scenarios would not be predicted from a whole-animal homogenate (Des Marteaux et al. Reference Des Marteaux, McKinnon, Udaka, Toxopeus and Sinclair2017, Reference Des Marteaux, Khazraeenia, Yerushalmi, Donini, Li and Sinclair2018).

Shifting from whole-animal to tissue-specific analyses must be done carefully, as inconsistencies in dissection technique or inadvertent inclusion of nontarget tissues (e.g., inclusion of fat body traces with gut samples) can lead to misleading results. Furthermore, tissues, organs, and organ systems may be improperly homologised. For example, the large, anterior portion of the midgut in cerambycid larvae has been misinterpreted as belonging to the foregut (Wei et al. Reference Wei, Lee, Gui, Yoon, Kim and Je2006; Choo et al. Reference Choo, Lee, Kim, Kim, Yoon, Sohn and Jin2007), likely leading to spurious reports of chitinase and cellulase enzymes in the foregut. Thus, it is important to standardise dissection and sample preparation protocols to ensure comparable results across samples within a study as well as among studies on the same or related species. Such standardised tissue classification (and developmental staging) protocols are de rigeur for model organisms (e.g., Sinha Reference Sinha1958; Eaton Reference Eaton1974; Bainbridge and Bownes Reference Bainbridge and Bownes1981; Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Carlson and Nelson1985; Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Ringo and Dowse1999).

Some cerambycid (longhorned) beetles are important forest pests (Eyre and Haack Reference Eyre, Haack and Wang2017). Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis Motschulsky; Coleoptera: Cerambycidae: Lamiinae) larvae feed on healthy tree tissues across a broad host range (Reference Faccoli, Favaro, Concheri, Squartini and BattistiFaccoli et al. 2016), and this species has been inadvertently introduced in North America and Europe (Nehme et al. Reference Nehme, Keena, Zhang, Sawyer and Hoover2010; Dodds and Orwig Reference Dodds and Orwig2011; Hull-Sanders et al. Reference Hull-Sanders, Pepper, Davis and Trotter2017). As with many economically important invasive species, the physiology and molecular biology of Asian longhorned beetle are the focus of current studies in multiple laboratories and countries. Thus, standardised dissection methods (currently unavailable for any cerambycid) are required to ensure appropriate tissue/organ identification and consistent sampling and comparisons.

Here we present a protocol for collecting haemolymph and dissecting six tissues/organs (the supraoesophageal ganglion, posterior midgut, hindgut, Malpighian tubules, fat body, and thoracic muscle) from Asian longhorned beetle larvae, distinguishing the appearance of the tissues in fresh and previously frozen specimens. This protocol should facilitate consistency among studies of Asian longhorned beetle and other cerambycid larvae and be useful for other beetles with similar larval morphology.

Protocol

Asian longhorned beetle larvae used in the present study originated from a laboratory colony derived from the Chicago (Illinois, United States of America) infestation and were reared under quarantine (Canadian Food Inspection Agency authorisation WA-2013-017) at the Insect Production and Quarantine Laboratory at the Great Lakes Forestry Centre (stock number: Glfc:IPQL:AglaUIC01; Great Lakes Forestry Centre, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada) (Roe et al. Reference Roe, Demidovich and Dedes2018). We reared larvae at 25 °C under constant darkness for 10 weeks and then exposed them to 7 °C to induce a developmental arrest (Keena and Moore Reference Keena and Moore2010). We sampled all larvae during this developmental arrest. We dissected live larvae at the Great Lakes Forestry Centre and freeze-killed larvae at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. Freeze-killed larvae had been flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen at the Great Lakes Forestry Centre and thereafter stored at −80 °C until shipping to the University of Western Ontario on dry ice.

External larval anatomy

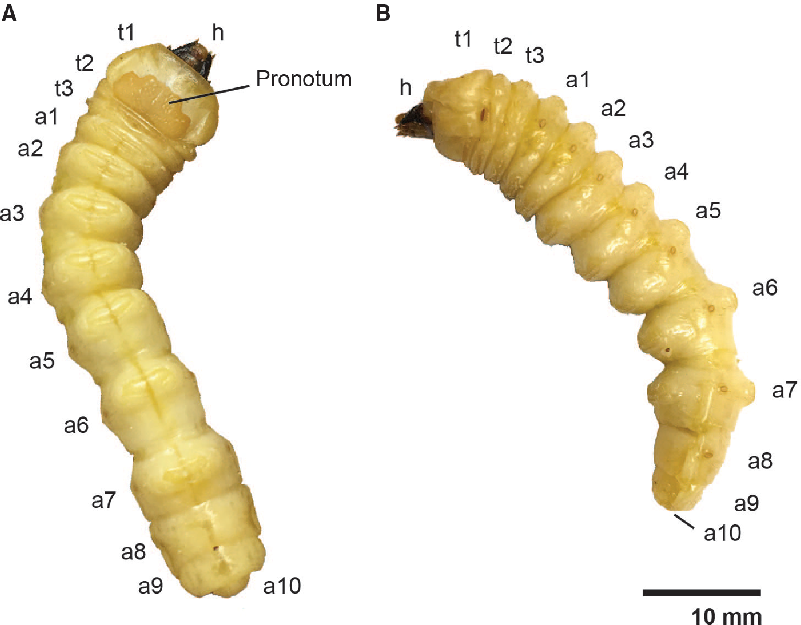

Asian longhorned beetle larvae are large, reaching up to 50 mm in length and weighing more than 1 g (Keena and Moore Reference Keena and Moore2010). The external anatomy of the cylindrical, cream-coloured larvae (Fig. 1) has been described in detail elsewhere (Cavey et al. Reference Cavey, Hoebeke, Passoa and Lingafelter1998) and is similar to that of other cerambycid larvae (Svacha and Lawrence Reference Svacha and Lawrence2014). The head is heavily sclerotised, prognathous, and partially retracted. The prothorax (Fig. 1: t1) is expanded relative to the mesothoracic and metathoracic segments (Fig. 1: t2 and t3) and has a partially sclerotised pronotum. The mesothoracic spiracle is well developed, and there are functional spiracles on the first eight abdominal segments (Fig. 1: a1–a8). The larvae lack both thoracic legs and abdominal prolegs: the virtual absence of thoracic legs distinguishes Lamiinae from other cerambycid subfamilies which (except for some Cerambycinae) have segmented legs.

Fig. 1. External larval anatomy of Anoplophora glabripennis. A, Dorsal view of the head (h), pronotum, thoracic segments (t1–3), and abdominal segments (a1–10); B, lateral view.

Haemolymph extraction

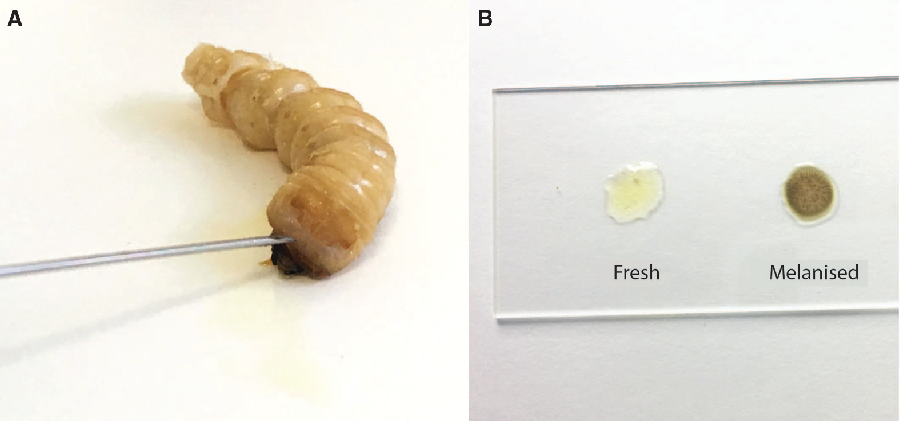

Prior to dissection, we punctured the anterior edge of the prothoracic shield cuticle of live larvae with a 22-gauge 1-inch needle (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Sunnyvale, California, United States of America) to create a bleeding wound (Fig. 2). We held the larva over a 1.5-mL tube to collect the haemolymph. The total volume of extracted haemolymph varied from 90 to 300 μL among individuals due to variation in larval size. We centrifuged the collected haemolymph for three seconds at 2000 × g to separate the haemolymph (infranatant) from lipids (supernatant) and other debris (high-density fraction). We used this low spin force to avoid separating haemocytes from the plasma of the haemolymph. We aliquoted known quantities of haemolymph for biochemical analyses into 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes and flash-froze them in liquid nitrogen. Evaporation should be minimised for some applications, such as measuring haemolymph osmolality. In these cases, we covered the haemolymph with a layer of mineral oil (M5904, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) before freezing to reduce evaporation. Haemolymph will begin to melanise after 15 minutes (Fig. 2B), so it must be processed quickly. Because freezing damages tissue and perturbs homeostasis, haemolymph from previously frozen larvae is probably not physiologically relevant, so while extracted haemolymph can be frozen, we do not recommend extracting haemolymph from previously frozen larvae.

Fig. 2. Haemolymph collection from Anoplophora glabripennis larvae. A, A bleeding wound was created by puncturing the anterior edge of the prothoracic shield; B, fresh haemolymph (left) and haemolymph that has melanised following 15 minutes exposure to air.

Internal anatomy and dissection

Larval dissection

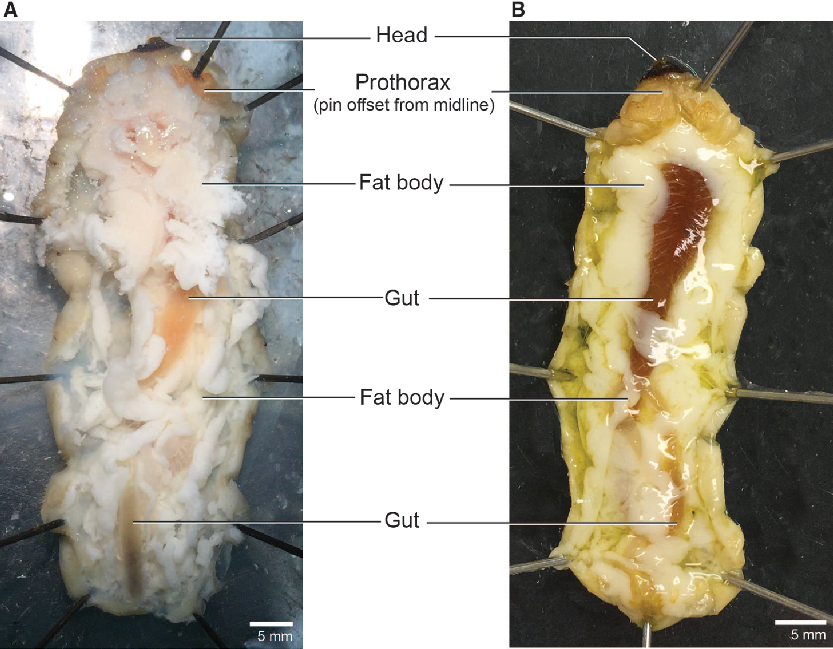

We dissected larvae in a dark-bottomed Sylgard-lined dish (Living Systems Instrumentation; Saint Albans City, Vermont, United States of America) that was deep enough (approximately 3 cm) to submerge the entire body in dissection medium of choice (examples below). We pinned the larvae through the sides of the prothorax (Fig. 1: t1) and the last abdominal segment (Fig. 1: a10) to hold it ventral side down with the body straight and the cuticle taut. We then cut through the cuticle along the dorsal midline anteriorly using microscissors held with the blades angled dorsally to avoid puncturing the gut. We spread the body walls laterally with 8–10 additional pins to open the body cavity and expose the internal organs (Fig. 3). To relax the tissues for easier dissection, frozen larvae were thawed and submerged in an aqueous solution chosen based on specific downstream needs (e.g., water, Ringer’s, or insect saline). Submerging fresh (unfrozen) specimens entirely in solution caused the fat body to dislodge and obscure other tissues; therefore, we pipetted 1–2 mL of an aqueous solution (as above) into the opened body cavity to wash away the fat body and relax the tissues of fresh specimens. We placed sampled tissues in a drop of fresh saline on a sterile Petri dish and cleared the samples of fat body and large (readily visible) tracheae and nervous tissue prior to flash-freezing in microcentrifuge tubes.

Fig. 3. Open body cavity. Larval morphology of the head, prothorax, fat body, and gut in Anoplophora glabripennis. A, Freeze-killed; B, fresh-killed.

Fat body, Malpighian tubules, and gut

The fat body occupies much of the larval internal cavity and obscures many internal organs, although the gut (orange or green in colour) is typically at least partly visible. We collected fat body samples from three areas: the lateral regions of the prothorax (Fig. 1: t3-a1), posterior midgut (Fig. 1: a4-a5), and hindgut (Fig. 1: a7-a9). We removed a total of approximately 300–500 mg for metabolite analysis and then removed and discarded all remaining fat body (an additional 300 mg could easily be collected from a medium-sized larva). Removing the remaining fat improves visibility of the gut and other organs (Fig. 4).

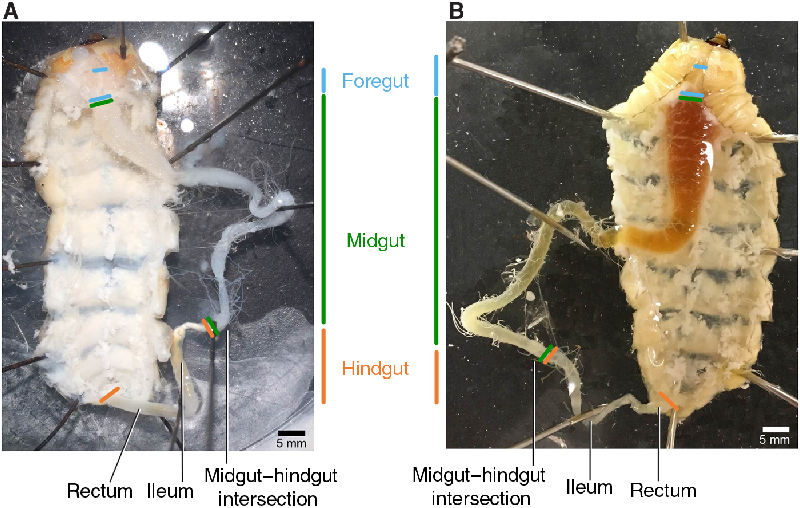

Fig. 4. Gut and associated structures. Foregut (blue), midgut (green), and hindgut (orange) of Anoplophora glabripennis larvae after removal of surrounding fat body. A, Freeze-killed; B, fresh-killed.

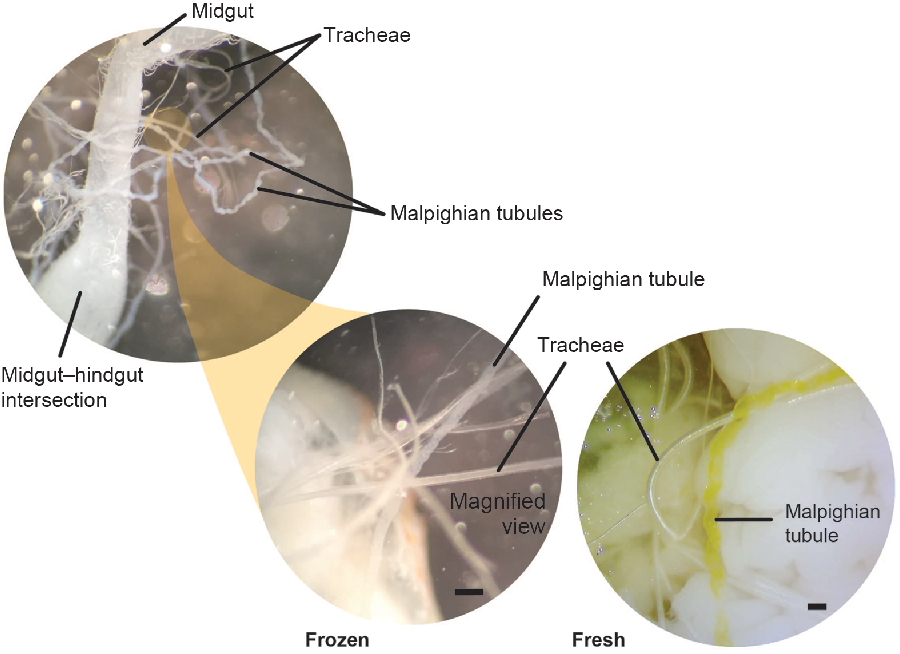

We collected the Malpighian tubules prior to removing the gut. The Malpighian tubules (which may be entangled in tracheae) attach at the bulbous midgut–hindgut intersection (Fig. 5). Because cerambycid larvae have cryptonephridial Malpighian tubules, we collected the free regions of the tubules prior to their entrance into the rectal wall. At this stage of the dissection, there are critical differences between fresh and freeze-killed specimens. For freeze-killed larvae, the gut may be pinned to one side away from the body to expose and isolate the Malpighian tubules. Multiple tracheae must be severed to liberate the gut, and this should be done carefully to avoid damaging the entwined Malpighian tubules (Fig. 5). Note that frozen larvae have white, rather than yellow, Malpighian tubules. Although the Malpighian tubules and tracheae both appear white in frozen larvae, the Malpighian tubules can be distinguished by their opaque, slightly flattened, and repeatedly curved (bumpy) appearance, while the tracheae, being internally supported by the cuticular taenidia (visible with specific lighting and/or higher magnification), appear cylindrical, hollow, shiny, and without repeated curves (Fig. 5). Although we could not pin the extremely fragile midguts of fresh larvae to the side, the Malpighian tubules of fresh larvae were bright yellow and therefore easily distinguishable from the tracheae. We used fine forceps to sever the Malpighian tubules from the base at the hindgut–midgut intersection.

Fig. 5. Malpighian tubules and tracheae. Morphological differences between the Malpighian tubules and tracheae in both freeze-killed and fresh-killed Anoplophora glabripennis larvae. The Malpighian tubules emerge at the midgut/hindgut boundary, appear opaque (cloudy), and are repeated curved (bumpy). Tracheae appear hollow, shiny, and smooth in appearance. Tracheae and Malpighian tubules are similar in colour in freeze-killed specimens, but tubules are bright yellow in fresh-killed larvae. Scale bars are 0.2 mm.

Morphological differences between the midgut and hindgut are clear in both fresh and frozen specimens; the junction between the gut regions is identifiable by a decrease in diameter, attachment of Malpighian tubules (Fig. 5), and (potentially) a change in colour (Fig. 4). To collect the hindgut, we severed the midgut–hindgut junction with microscissors. We sampled the posterior midgut by collecting a 2.0–2.5 cm section of gut anterior to the midgut–hindgut junction. After dissecting each gut section, we cut open the section, removed the solid contents (food bolus) with forceps, and then rinsed the tissue with fresh insect saline (note that a portion of the gut luminal microbiota will likely remain in the gut folds). Inclusion of the gut contents for downstream analyses (e.g., microbiome; Scully et al. Reference Scully, Geib, Carlson, Tien, McKenna and Hoover2014) can be achieved by clamping the gut closed at each end prior to severing the tissue (see MacMillan and Sinclair Reference MacMillan and Sinclair2011).

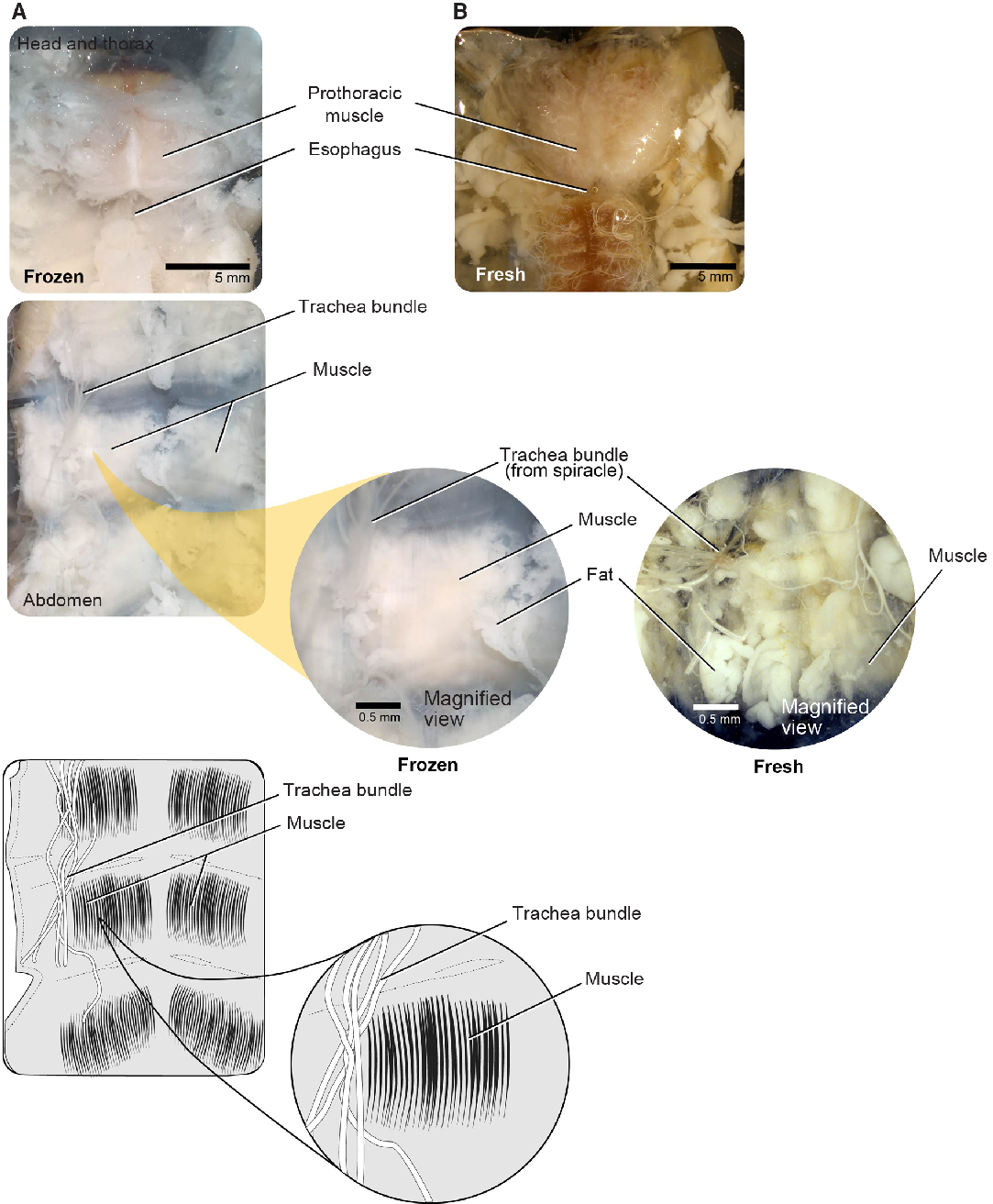

Muscle

Large muscle bundles are found in the prothorax and attached to the body wall of each thoracic and abdominal segment and are among the easiest tissue to sample. We sampled muscle bundles within the prothorax (i.e., the main dorsal head retractor and pharyngeal muscles) (Fig. 6). These firm, striated muscles are easily distinguishable from other musculature in both fresh and frozen individuals. We used forceps or microscissors to remove prothoracic muscle (making cuts away from the midline), being careful to avoid damaging the nervous tissue such as the supraesophageal ganglion or nerve cord along the midline (see below).

Fig. 6. Musculature for both freeze-killed and fresh-killed Anoplophora glabripennis larvae. A, Head and thorax; B, abdomen.

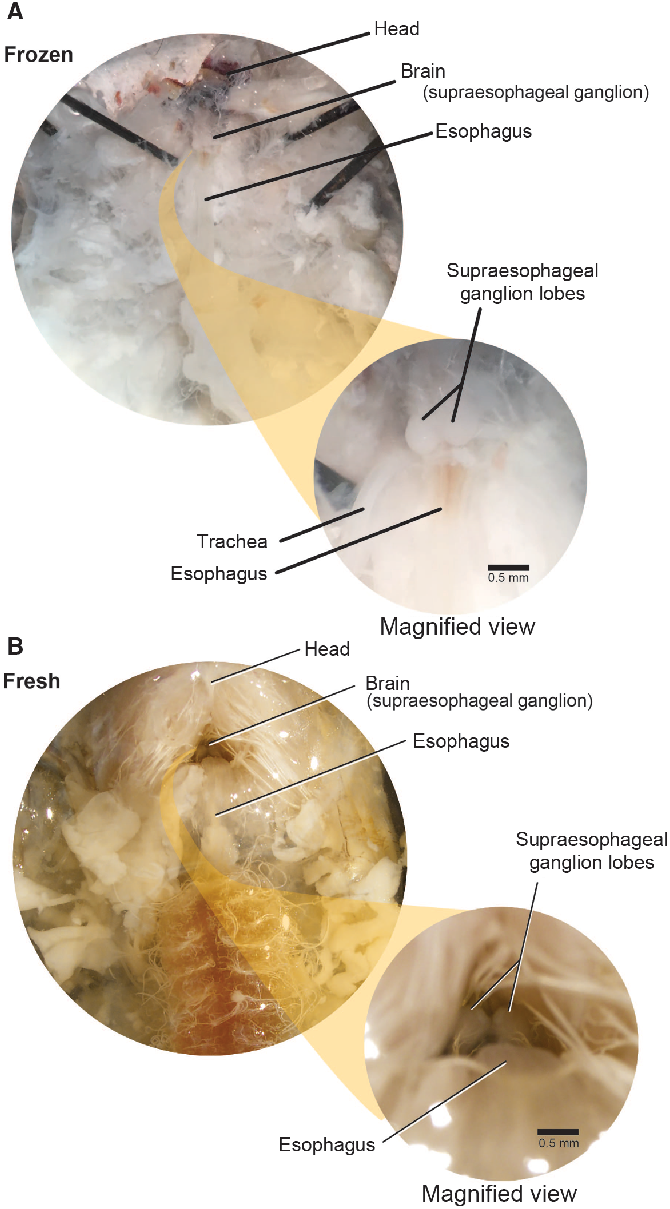

Supraoesophageal ganglia

The brain (supraoesophageal ganglion) is composed of two lobes placed above the oesophagus within the sclerotised cranium, which is retracted beneath the pronotum (Fig. 7). We used the oesophagus as a guide to locate the brain. First, we carefully exposed the oesophagus by pushing the posterior cranial margin up and forward. This helps to expose the brain, allowing access to it through the occipital foramen. To extract the brain, we gently severed the circumoesophageal nerve ring with microscissors or forceps and removed the brain with forceps.

Fig. 7. Supraoesophageal ganglia. The supraoesophageal ganglia (brain) of Anoplophora glabripennis larvae lies dorsal to the oesophagus and ventral to the prothoracic muscle. The ganglion lobes are easily distinguished from surrounding tissue in both frozen and fresh-killed specimens. A, Frozen specimens; B, fresh-killed specimens.

Discussion

There are more than 36 000 described Cerambycidae species (Monne et al. Reference Monne, Monne, Wang and Wang2017). Consistent dissection approaches, such as those outlined here, should facilitate tissue-specific physiological and molecular research for Asian longhorned beetle and related cerambycids even for nonmorphologists. The large size of Asian longhorned beetle larvae allows tissue harvesting for multiple purposes (e.g., samples destined for both physiological assays and genotyping), providing an opportunity to associate physiology with population genetic information; an approach that can inform mechanistic species distribution models for invasive species (Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Urban, Angilletta, Crozier, Rissler and Sears2010).

Haemolymph collection is perhaps the most time-dependent component of the protocol we describe. Melanisation in Asian longhorned beetle is fairly fast, so haemolymph should be sampled, processed, and stored within 15 minutes. Haemolymph samples destined for assays such as haemocyte counts or metabolite concentrations can be flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For other downstream measurements (e.g., haemolymph osmolality), it is necessary to store the samples under mineral/immersion oil or in a capillary tube to prevent evaporation. Note that freezing disrupts cellular integrity, thus haemolymph collected from previously frozen specimens may contain products from ruptured cells of various tissues. One potential solution to this problem would be to centrifuge at a higher speed to remove cells and large cellular debris.

We expect this protocol to be generally applicable throughout Cerambycidae, although species-specific differences in tissue size and appearance are likely. For example, because cerambycid larvae range from approximately 5–200 mm in length (Lawrence Reference Lawrence and Stehr1991), we expect that tissues of smaller individuals may be difficult to dissect and differentiate and may not yield sufficient material for some downstream applications (e.g., RNA-seq). In such cases, tissue samples from multiple individuals can be pooled. Larval morphology among beetle families can vary significantly; however, the methods outlined here should be generalisable to families with similar morphology to Cerambycidae.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the technical staff in the Insect Production and Quarantine Laboratories at the Great Lakes Forestry Centre for their work in rearing specimens used for the development of this protocol. We would also like to thank Petr Švácha for lending his expertise to improve earlier drafts of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Genome Canada, Genome British Columbia, and Genome Quebec (LSARP 10106; Genome Canada) grant for the Biosurveillance of Alien Forest Enemies (BioSAFE).