Introduction

Iodine is an essential component of thyroid hormones; required for normal cognitive function and metabolism throughout life(Reference Velasco, Bath and Rayman1). During pregnancy, maternal iodine and thyroid hormones are required for fetal neurogenesis, including axon and dendrite growth, synapse formation, myelination and neuronal migration. Iodine is solely obtained from dietary sources, primarily dairy products, and seafood in the United Kingdom (UK), or supplements(Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet2). At the moment, in the UK, there is no requirement for iodine fortification and iodised salt is available in very few retail outlets(Reference Bath, Button and Rayman3,Reference Shaw, Nugent and McNulty4) , while antenatal care guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) make no mention of iodine nutrition(5). The most recent National Diet and Nutrition Survey found that, although children met the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of iodine sufficiency, women of child-bearing age (16–49 years of age) did not(6).

Iodine requirements increase by approximately 50 % during pregnancy, leaving this population potentially vulnerable to iodine deficiency(Reference Velasco, Bath and Rayman1). This may be compounded by the exclusion of iodine-rich foods due to the following of vegetarian or vegan dietary patterns or the exclusion of foods during pregnancy such as smoked fish, raw shellfish, marlin and shark as well as advising to limit portions of oily fish to two per week due to concerns regarding heavy metal toxins, as well as difficulties with the symptoms of nausea and vomiting(7). Iodine deficiency in pregnancy is the leading cause of mental retardation in children worldwide(Reference Aburto, Abudou and Candeias8,Reference Chen and Hetzel9) . The effects of severe iodine deficiency on fetal development are well recognised(Reference Toloza, Motahari and Maraka10,Reference Verhagen, Gowachirapant and Winichagoon11) ; the effects of mild to moderate iodine deficiency are less well established(Reference Verhagen, Gowachirapant and Winichagoon11). It has been suggested that mild iodine deficiency in pregnancy may result in lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores in offspring; as well as increased risk of perinatal complications(Reference Abel, Caspersen and Sengpiel12,Reference Trumpff, De Schepper and Tafforeau13) . Some population studies have supported this, as maternal iodine deficiency-induced thyroid dysfunction has been, albeit inconsistently, linked to impairments in intellectual and behavioural function in offspring(Reference Velasco, Bath and Rayman1,Reference Bath and Rayman14–Reference Wang, Han and Chen16) .

Historically, in the UK, there was a high prevalence of endemic goitre due to iodine deficiency; changes in livestock feeding patterns and government endorsement of cows’ milk intake improved the iodine status of the UK population and eradicated endemic goitre by the middle of the 20th century. Despite the need for regular population monitoring being noted, the iodine nutrition status of the UK population was not routinely monitored for many years(Reference Phillips17). Outside of the UK, iodine fortification in the form of iodised salt has been implemented in a number of countries since its recommendation by the WHO in 1993(18). For example, in 1996, China implemented a universal salt iodisation policy following in the footsteps of the United States of America and Switzerland who have iodised salt since the 1920s(Reference World Health Organization19,Reference Wang, Wu and Shi20) .

In 2009, Vanderpump studied the urinary iodine concentration (UIC) of schoolgirls (14–15 years old) across the UK and found this population to be iodine deficient. The prevalence of iodine deficiency was highest in the Belfast centre, with 85 % of participants having UIC within the deficient range as defined by the WHO (<100 μg/l)(Reference Vanderpump, Lazarus and Smyth21).

A further cohort from the island of Ireland, which included a centre in Belfast, showed low-level sufficiency in the same schoolgirl age range(Reference Mullan, Hamill and Doolan22). A study of pregnant women from the same Belfast centre showed iodine deficiency, with a median UIC below the WHO recommended cut-off in pregnancy (150 μg/l), despite 55 % of participants reporting taking a supplement containing iodine(Reference McMullan, Hamill and Doolan23). This highlights the vulnerability of pregnant populations to iodine deficiency, particularly in the recently demonstrated precarious setting of low-level sufficiency as observed in the school-age population in the UK(Reference Woodside and Mullan24). Improving awareness of this issue via public health campaigns targeting vulnerable groups may play an important role in improving iodine nutrition, along with consideration of fortification, supplementation during pregnancy and lactation, and midwife education(Reference Bookari, Yeatman and Williamson25).

Pregnancy is often seen as an opportunity to effect behavioural change, as women are motivated and contact with health professionals is routine(Reference Bookari, Yeatman and Williamson25–Reference Ayyala, Coughlin and Martin27). There is the unique motivation to have a healthy pregnancy, delivery and baby, but there are still barriers to positive lifestyle change including lack of knowledge(Reference Ayyala, Coughlin and Martin27). Therefore, care received during pregnancy and the perinatal period may help to capitalise on a woman's motivation by helping them overcome the relevant barriers and providing advice on relevant nutritional issues(Reference Atkinson, Shaw and French26,Reference Ayyala, Coughlin and Martin27) . However, there have been few studies exploring knowledge of iodine among women of child-bearing age and the healthcare professionals (HCPs) involved in providing antenatal care. Without this knowledge, behavioural change to improve iodine status is unlikely to occur(Reference Atkinson, Shaw and French26).

The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) reviewed the topic of iodine nutrition in 2014, calling for further research into iodine intake in the UK, particularly in vulnerable groups including during pregnancy and lactation, prior to recommendations regarding fortification or supplementation being made(28). Meanwhile, despite the lack of high-quality evidence or trials concerning the effect of iodine supplementation on fetal outcomes, a number of health authorities worldwide, including in Australia and Croatia where iodine fortification is mandatory, have decided to include the recommendation for iodine supplementation during pregnancy and lactation in their guidelines for antenatal care(29,Reference Vidranski, Radman and Kajić30) .

Despite the public health campaigns to improve awareness of and uptake of folic acid, another micronutrient with a vital role during early pregnancy, less than half of women are aware of the role of folic acid or the need to take supplements in the perinatal period(Reference Rofail, Colligs and Abetz31). This is further complicated by the rate of unplanned pregnancy in the UK of 45 %(Reference Wellings, Jones and Mercer32). Pregnant women in the UK are entitled to a free ‘Bounty Pack’, which is often provided at their booking clinic appointment. This includes various information and advertising material some of which support the use of Vitabiotics Pregnacare, the leading pregnancy supplement in the UK. All varieties of Pregnacare contain iodine in the form of potassium iodide at a dose of between 140 and 200 μg/d(33). However, there has been criticism of the timing of this as the first trimester, which is the key time for neurodevelopment, has already been completed and therefore any benefit may be limited.

This literature review aims to identify and evaluate studies relating to knowledge of the role of iodine during pregnancy among HCPs and patients in the UK. This will be set in the context of iodine knowledge globally. This will summarise the current evidence base, particularly while more data regarding iodine intake and deficiency in vulnerable populations, including during pregnancy, as requested by SACN, is generated to allow appropriate decision-making regarding the implementation of iodine supplementation during pregnancy and lactation and mandatory fortification of foods such as salt.

Methods

To capture relevant papers, the term ‘iodine knowledge’ was entered into the ‘PubMed’ search engine and the Queen's University Belfast (QUB) library catalogue. Search filters to include papers available in English language were used. Searches were completed between October 2020 and April 2021. Women of child-bearing age were defined as women between 18 years and 45 years old. Professions included under the title of HCP were midwives, dieticians and doctors (of any speciality). Abstracts were reviewed for relevancy and those papers looking at iodine knowledge of HCPs and patients were downloaded in full and separated into the UK and international papers. Papers were then reviewed in full by one author (LK); initially only those that specifically mentioned iodine knowledge were included, but as there were so few papers relating to HCPs knowledge of iodine, papers that had been found during the search with a more general focus on nutrition knowledge of HCPs in pregnancy were also considered eligible. The search was then repeated using the term ‘iodine awareness’ and similar process followed.

Patient knowledge

Four papers examining iodine knowledge of patients within the UK were identified. Most studies used questionnaires while one used qualitative methodology. Table 1 shows a summary of the findings from studies of patient iodine knowledge in the UK. Key themes from studies in the UK were that iodine knowledge is low among women of child-bearing age, they are unsure of dietary sources of iodine and they are not consistently provided with relevant information from HCPs(Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet34–Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37).

Table 1. Summary of papers from the UK reporting iodine knowledge in women of child-bearing age

There was general agreement among participants that there was a lack of information provided on iodine. In the cohort studied by Bouga et al., a quarter of women reported no discussion around nutrition in pregnancy and that advice regarding iodine was insufficient, with education, when given, focusing on foods to avoid and dietary supplements(Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet38). In the cohort of women of child-bearing age studied by O'Kane et al., only 9 % had previously received information about iodine and 75 % reported this was during formal education rather than as part of clinical care(Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37). The 12 % of participants in the study by Combet et al. who reported receiving sufficient iodine information in pregnancy did not have a significantly higher iodine intake, however, the 64 % who had received sufficient information on calcium did have significantly higher iodine intakes from food and supplements throughout pregnancy compared with those who had reported not receiving sufficient information(Reference Combet, Bouga and Pan35). It was also noted that multiparous women reported receiving less information in their current pregnancy than during their first pregnancy, as prior knowledge was assumed(Reference McMullan, Hunter and McCance36,Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet38) .

Women were unaware of dietary sources of iodine. In the study by Combet et al., 56 % were unable to identify any iodine-rich food, but incorrectly identified dark green vegetables and salt as good sources of iodine in the UK, where salt is not required to be fortified with iodine and there is low availability of iodised salt(Reference Bath, Button and Rayman3,Reference Shaw, Nugent and McNulty4,Reference Combet, Bouga and Pan35) . This was similar to the 45 % of participants who were unsure of dietary sources of iodine in the cohort studied by McMullan et al. (Reference McMullan, Hunter and McCance36). Milk and dairy products, the largest dietary contributors to iodine intake in the UK, were identified as iodine rich by only 9 % of women in this study and a similar proportion of the participants in the study by O'Kane et al. (Reference McMullan, Hunter and McCance36,Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37) . A great percentage of women in both cohorts identified fish as an iodine-rich food source with 30 and 39 %, respectively(Reference McMullan, Hunter and McCance36,Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37) .

The study by O'Kane et al. was advertised through a local higher education institution, resulting in a cohort with greater knowledge than would be expected in the general population and included women of child-bearing age rather than those who are or have been pregnant, and therefore participants may not have been exposed to antenatal care. Despite this assumed greater knowledge, 46 % of participants did not meet the recommended daily intake of iodine calculated by food frequency questionnaire and few correctly identified dietary sources of iodine(Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37). This and one other study reported that increased maternal age and higher educational attainment were associated with significantly higher total iodine knowledge scores(Reference Combet, Bouga and Pan35,Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37) . Higher intake of iodine-rich foods (fish and dairy products) was positively associated with iodine knowledge and knowledge of health problems associated with iodine deficiency(Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet2,Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet34,Reference McMullan, Hunter and McCance36,Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37) .

There was, in general, a willingness to change dietary behaviours in pregnancy when provided with specific advice by HCPs with supplementary information for future reference(Reference Combet, Bouga and Pan35). For example, women reported reducing or eliminating fish in their diets due to concern regarding heavy metals and toxins resulting in potential harm to their baby, following nutrition advice(Reference Combet, Bouga and Pan35,Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet38) .

Professional knowledge

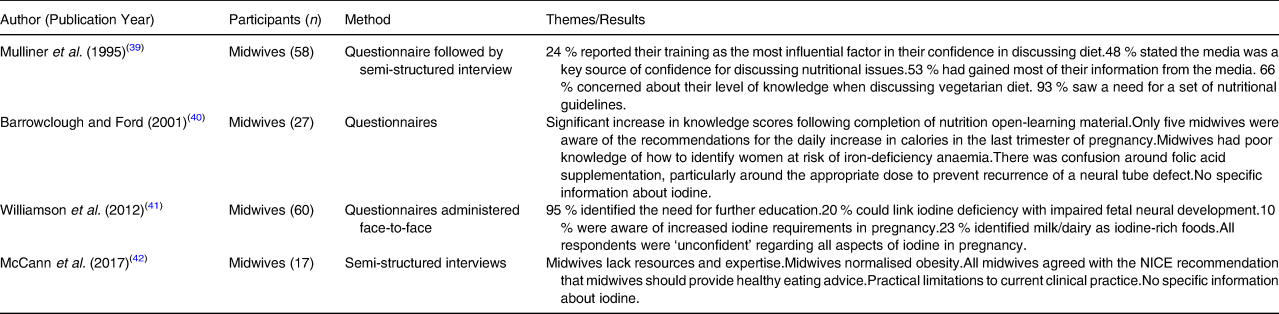

Four papers relating to UK HCPs’ iodine and nutrition knowledge were reviewed. Table 2 shows a summary of these papers. In the UK, midwives provide routine antenatal care and community midwives have been recognised as the main providers of dietary information during pregnancy(Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet2). The papers highlight that, although midwives are aware of the importance of their role as nutrition advisors, they do not feel adequately equipped to perform it and lack confidence in addressing nutritional concerns(Reference Bouga, Lean and Combet2,Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39–Reference McCann, Newson and Burden42) .

Table 2. Summary of papers discussing midwife knowledge of nutrition and iodine in the UK

The study by McCann et al. focused on obesity and discussed midwives’ experiences of weight management advice as well as the broader topic of healthy eating. This cohort reported high workload, along with the normalisation of obesity, and lack of knowledge as reasons for the lack of dietary advice provided as part of routine antenatal care. The midwives in this study were aware of the health risks associated with poor diet and obesity in pregnancy but lacked the confidence and skills to give appropriate advice(Reference McCann, Newson and Burden42). It was recognised that a lack of support in midwifery training may impact on the qualified midwife's ability to perform their role as nutrition educator, and many midwives indicated the need for further education(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39,Reference McCann, Newson and Burden42) .

Barrowclough et al. developed open-learning materials for midwives on the topic of perinatal nutrition. Participants had a statistically significant increase in knowledge score after completion of training via the materials. Topics included weight gain and recommended an increase in calorie intake during pregnancy, folic acid supplementation and iron-deficiency anaemia(Reference Barrowclough and Ford40). However, it was noted that this style of learning is time-consuming, with a minimum of 6 h required to complete this package determined during a pilot study, although the time taken by each participant was not recorded. Implementation of this style of learning would require support from managers to ensure sufficient study time is allowed for busy practicing midwives(Reference Barrowclough and Ford40). This open-learning pack did not include the topic of iodine nutrition, although it could be developed to include this and other topics at a variety of academic levels(Reference Barrowclough and Ford40,Reference Sandanayake, Karunanayaka and Madurapperuma43) .

The papers by Mulliner et al. and Williamson et al. addressed the subject of iodine knowledge in HCPs, but only included midwives. There are similar findings in the two studies despite 17 years having elapsed between their publication. Each study encompassed only one health authority within the UK, and both included small numbers (58 and 60, respectively) when compared with the estimated 39 000 currently registered midwives within the UK(44). In both cohorts, a need for further education and clinical guidelines was reported(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39,Reference Williamson, Lean and Combet41) .

The questionnaire used by Mulliner et al. focused on knowledge and a marking scheme was established by circulating the relevant section to a dietician, a consultant obstetrician and three midwives and comparing key areas identified by them with the researcher's expectation. They report that consensus was reached without difficulty and key questions were given extra weight(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39). In contrast, Williamson et al. asked midwives to rate their confidence on a Likert scale. Most midwives in this cohort saw women in the last two trimesters of pregnancy, 18 % were community based and only 2 % routinely provided advice on iodine nutrition(Reference Williamson, Lean and Combet41). Participants rated knowledge on general nutrition ‘very confident’ and ‘confident’ for dietary guidelines, but ‘unconfident’ for all aspects of iodine nutrition, without any formal assessment of knowledge(Reference Williamson, Lean and Combet41).

Since the publication of Mulliner et al. in 1995, NICE have published guidance on maternal and child nutrition, and antenatal care. However, neither guideline includes any information around iodine nutrition in pregnancy, instead focusing on folic acid and foods to be avoided in pregnancy(5). The omission of iodine from the NICE guidelines and other antenatal resources, such as the ‘Pregnancy Book’ in Northern Ireland and ‘Ready, steady, baby!’ in Scotland, may reflect the lack of iodine awareness among professionals and policymakers, as well as the ongoing need for good quality evidence as highlighted by SACN(45).

Midwives reported lack of time, lack of knowledge and lack of confidence as the barriers to providing nutrition education in pregnancy(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39). The importance of nutrition as part of health promotion periconceptually has been recognised, but, given the large amount of knowledge midwives have to gain during their undergraduate studies, it seems to be less of a priority during this time(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39).

There is currently no information regarding UK clinicians’, and other HCPs’, knowledge of iodine nutrition and, although the General Medical Council recommend that doctors should be able to meet support patients to meet their nutritional needs, a study of final year medical students found they had poor knowledge of nutrition(Reference Broad and Wallace46). This means the lack of knowledge among midwives may not be offset by other HCPs.

International context

Globally, as in the UK, there is a lack of iodine knowledge among women and HCPs. Five papers from outside the UK focusing on patient iodine knowledge were examined. Table 3 shows a summary of findings from studies around the globe regarding patients’ iodine knowledge. Two of these were from Australia where there has been a focus on iodine nutrition recently following the re-emergence of iodine deficiency and the introduction of iodine fortification. Iodine knowledge has improved post-fortification and more women reported receiving adequate information on iodine during pregnancy after the publication of the updated National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines including iodine(Reference Charlton, Yeatman and Lucas47).

Table 3. Summary of international papers discussing women of child-bearing age's iodine knowledge.

HCP, healthcare professional; N/A, not applicable.

Iodine status is taken as the proportion of population with urinary iodine concentration <100 μg/l (deficient) from the most recent World Health Organization survey, data collected 1993–2003.

As in the UK, midwives are the main providers of antenatal care and their role as a source of health and nutrition information in pregnancy has been recognised in Australia(Reference Arrish, Yeatman and Williamson48). However, their ability to provide the necessary information may be limited by a lack of knowledge and skills. The midwifery undergraduate curriculum includes nutrition, although teaching hours are reported to be low, and the focus not on practical training(Reference Arrish, Yeatman and Williamson49). In one survey, most midwives had received nutrition education, but it was generally described as limited. The cohort in this study, as in others, reported a need for further nutrition education, with 94⋅2 % feeling this would benefit their clinical practice(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39,Reference Arrish, Yeatman and Williamson49) .

Awareness of the updated NHMRC guidelines was a statistically significant predictor of advising on iodine supplementation during pregnancy(Reference Guess, Malek and Anderson50). Midwives were the least likely HCPs to recommend iodine supplements, with dietitians being the most likely followed by general practitioners, and obstetricians and gynaecologists. Most midwives reported a lack of knowledge as the main reason for not discussing dietary sources of iodine. This was different from other HCPs, who stated lack of time as the main reason for not discussing this topic. In the present study, 57 % of midwives were aware of the NHMRC recommendation for iodine supplementation, although only 18 % knew the recommended dose. Almost all HCPs, from all disciplines, were interested in receiving more information about iodine nutrition, in particular the NHMRC recommendations and dietary sources of iodine(Reference Guess, Malek and Anderson50).

The population studied by Wang et al. in China, a country with a well-established salt iodisation programme, showed a significant difference between the UICs of those with ‘poor iodine knowledge score’ and ‘high iodine knowledge score’. They found that iodine-related knowledge, having a habit of consuming iodine-rich food (including iodised salt), actively seeking dietary knowledge and trimester of pregnancy were associated with significantly higher UIC(Reference Wang, Wu and Shi20).

Poor iodine knowledge has been recognised as a factor contributing to iodine deficiency(Reference O'Kane, Pourshahidi and Farren37,Reference Charlton, Yeatman and Lucas47) . However, improving iodine knowledge alone may not be sufficient for women to achieve iodine sufficiency in pregnancy, although it may affect behaviour around supplementation(Reference Piirainen, Isolauri and Lagström51,Reference Popa, Niţă and Graur52) and these concerns are supported by the ongoing difficulties faced implementing changes to behaviour around folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects (NTDs).

Iodine in the context of folic acid

There are potential lessons to be learned from the delays in policymaking around folic acid, preconception supplementation and fortification in the UK. Despite the recommendations regarding folic acid that women take a 400 μg supplement of folic acid before pregnancy and for 12 weeks after conception(5), and associated public health campaigns, compliance remains low(Reference Stockley and Lund53) with one study reporting that 31 % of women reported taking folic acid supplements as recommended by the NICE guidelines(Reference Barbour, Macleod and Mires54). This low uptake is likely to be influenced by the rate of unplanned pregnancies and the fact that in the UK HCP contact and nutrition counselling occurs at the end of the first trimester.

In 2006, the SACN recommended fortification of flour with folic acid in the UK. This was due to the poor compliance with folic acid supplementation, particularly in deprived socio-economic groups, and the number of unplanned pregnancies in the UK making preconceptual supplementation difficult(Reference Wellings, Jones and Mercer32,55) . It has been estimated that 2000 births have been affected by NTDs between 1998 and 2012, that may have been prevented if folic acid fortification had been implemented in 1998, the same year it was made mandatory in the US(Reference Morris, Rankin and Draper56).

In one cohort, women reported receiving information on folic acid around 12 weeks gestation, at which time it was deemed redundant. However, the proportion of women taking folic acid does increase after confirmation of pregnancy(Reference Bestwick, Huttly and Morris57,Reference Jawad, Patel and Brima58) . Women also reported no particular emphasis on the topic during antenatal care(Reference Barbour, Macleod and Mires54). This may be explained, as with iodine, by a lack of knowledge among HCPs as there was confusion around the recommendations for folic acid in a cohort of midwives in the UK(Reference Barrowclough and Ford40).

Factors linked to lower rates of folic acid supplement use are unintended pregnancy, age, socio-economic and ethnic group(Reference Stockley and Lund53). Initiatives, integrated into healthcare, can be effective, but are more likely to be successful if they include making supplements easily available. Using printed resources is less effective for women in lower socio-economic groups. There is also lower awareness of folic acid recommendations in these groups, and the current folic acid policy may exacerbate health inequalities(Reference Stockley and Lund53,Reference Bestwick, Huttly and Morris57) . In contrast, information received from HCPs has been associated with changes in modifiable behaviours, including taking folic acid supplements(Reference Jawad, Patel and Brima58–Reference Stephenson, Patel and Barrett61).

Future research

There is a need to review nutrition education within the current undergraduate curriculum for HCPs; including potentially, not only the transmission of knowledge, but practical instruction on motivational interviewing techniques to provide HCPs with the knowledge and confidence to discuss these issues with women prior to pregnancy and during antenatal care. This should overcome some of the barriers to providing nutrition information cited by midwives in the limited research currently available. Other barriers, including lack of time and the belief that discussion will not result in behavioural change, may be more difficult to tackle. Awareness of preconception health among women and HCPs is low and responsibility for providing preconception care is not well defined. This is problematic as first contact with HCPs is generally around 12 weeks gestation, after the initial period of fetal development. Modifiable factors, such as maternal diet and nutritional status, have an important influence on the intrauterine environment and fetal development(Reference Stephenson, Patel and Barrett61).

To examine the potential cost of implementation of iodine supplementation within the National Health Service, one group performed cost analysis of iodine supplementation for 13 weeks preconception continuing through pregnancy and lactation(Reference Monahan, Boelaert and Jolly62). The model used was based on a conservative approach limiting the potential benefits of iodine supplementation and overestimating its potential harms. The main effect examined was of reduced IQ in offspring based on the economic and societal cost implication. A reduced IQ is associated with an increased rate of mortality with a higher risk of suicide and mental ill health as well as a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease. Overall, with a conservative estimate of a discounted lifetime value of an additional IQ point of £3297, iodine supplementation was cost-effective with a net gain of 1⋅22 IQ points(Reference Monahan, Boelaert and Jolly62). Estimates of cost were based on earnings from the United States in 1974 and 1990 and do not take into account the advances in technology in the work place which may increase the value of an additional IQ point to today's workforce(Reference Monahan, Boelaert and Jolly62).

The impact of iodine supplementation on maternal health is less clear. One meta-analysis showed no benefit of iodine supplementation in pregnant women with mild iodine deficiency; although this may be due to the physiological adaptation of the thyroid gland to maintain thyroid hormones at a normal level for fetal development, even in the setting of low iodine intake(Reference Nazeri, Shariat and Azizi63). There were only five papers relating to maternal health outcomes. Differing formulations and doses of iodine supplementation were used and supplementation was commenced between 10 and 18 weeks gestation which may be too late to see benefit(Reference Nazeri, Shariat and Azizi63).

The SACN report on iodine highlights the need for further research into the safety and efficacy of iodine supplementation in pregnancy, as well as the development of a biomarker of iodine deficiency at an individual level. There are practical and ethical issues limiting the study of iodine supplementation before preconception and during pregnancy and lactation. A placebo-controlled trial could be considered unethical if there is potential benefit from iodine supplementation as well as the practical difficulties of recruiting women early in pregnancy when fetal neurodevelopment takes place. However, the requirement for high-quality evidence to inform UK policy and guidelines is clear, the need for which were highlighted by practicing midwives(Reference Mulliner, Spiby and Fraser39).

Our group is currently carrying out qualitative research aiming to understand UK midwives’ current iodine knowledge, their experience of nutrition education during their undergraduate studies and their views on their role and responsibility to provide nutrition information to women. We are also performing an intervention study with pregnant women completing an iodine knowledge questionnaire before and after the provision of an information leaflet as part of a larger study.

Conclusion

Midwives’ knowledge of iodine and its role in healthy pregnancies is poor according to the limited studies to date within the UK. This is reflected by poor knowledge in women of child-bearing age, even in those who have received dietary advice as part of routine antenatal care. Globally, there was poor knowledge of iodine among HCPs, however the effects of this may be mitigated by the implementation of fortification and supplementation, such as in Australia and Croatia. This review is limited by the lack of a validated iodine knowledge questionnaire, making comparisons more difficult, and by the lack of data on iodine status on the UK within the latest WHO worldwide survey. Improving iodine status, particularly in pregnancy, should be a priority within the UK to prevent a similar missed opportunity as with folic acid. Improved HCP knowledge and effective communication of information to pregnant women or women planning to conceive is one step in this process. Australia may offer an example for the UK to follow, with several similarities, including poor HCP knowledge of iodine, although Australia has moved forward with the implementation of iodine supplementation in their latest antenatal guidelines. In the absence of mandatory iodine fortification, low availability of iodised salt, lack of guidance on iodine supplementation prior to or during pregnancy and lactation in the UK, raising HCP knowledge and awareness of iodine deficiency as a current public health concern in the UK is essential.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by HSC R&D Division, Public Health Agency [LK, grant number EAT/5578/19].

L. K. was responsible for writing and content. K. M. and J. W. were responsible for conceptualisation and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.