Introduction

Total institutions are geographically delimited places of residence and work, where people live a regulated life for extended periods of time, separated from the outside world [Goffman Reference Goffman1961]. To the extent that these forms of institutions are all-encompassing, they are by definition totalitarian, but they are commonly also assumed to be authoritarian. For example, to suggest that organizations tend to be “contested terrains rather than total institutions” [Clegg Reference Clegg1989: 107] implies that there is little “polyphony” and few conflicting voices in total institutions [see also Clegg et al. Reference Clegg, Courpasson and Philips2006: 150]. While authoritarianism is undoubtedly a feature of some total institutions such as extermination camps [Clegg et al. Reference Clegg, Pina E Cunha and Rego2012], it is not necessarily an adequate characterization of all species of total institutions. Goffman [Reference Goffman1961] mentioned mental hospitals, homes for the elderly, boarding schools, military camps, and monasteries as examples of different total institutions. One crucial distinction among these different types concerns how people enter them [see also Davies Reference Davies1989]. Whereas involuntary total institutions forcibly induct inmates and keep them there against their will, voluntary total institutions consist of members who have chosen to enter, and who are also free to leave. Hirschman’s [Reference Hirschman1970] classic thesis in Exit, Voice and Loyalty asserts that, when confronting organizational problems, people face the option of either leaving the organization (exit) or staying and expressing their displeasure (voice). Consequently, it is relevant to consider both exit and voice in relation to voluntary total institutions.

In this article, I focus on Catholic monasteries within the Cistercian Order of Strict Observance as a specific case of voluntary total institution. I ask the following two questions: what opportunities for voice do monastic members have?Footnote 1 And what are their opportunities for exit? Like many Catholic monastic orders, professed Cistercians have promised to live the rest of their lives within one monastic community (the vow of stability), to obey their abbot/abbess and put their own will aside (the vow of obedience), and to live the monastic life, in all its parts, as described by the Rule of Saint Benedict and the Constitutions of the Order (the vow of conversion of manners). At face-value, the vows of stability and obedience, in particular, imply that monasteries should exhibit neither exit nor voice, but silent loyalty. What is the situation in practice?

The general trend is that fewer and fewer new members enter Catholic monasteries and that the total number of members is decreasing [see e.g. Jonveaux Reference Jonveaux, Jonveaux and Palmisano2016; Dalpiaz Reference Dalpiaz2014]. Beyond discussions on the decline of membership, recent sociological research on monastic exit is limited. Ebaugh [Reference Ebaugh1988] interviewed former Catholic nuns in a study of exits from various significant roles, but provides few insights into the specific case of monasteries. Ebaugh [Reference Ebaugh1977] also conducted an extensive study of female religious orders in the US a few years after the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), a reform that brought immense changes to Catholicism and its monastic life. Research on voluntary associations shows how influence in decision-making increases commitment [Barakso and Schaffner Reference Barakso and Schaffner2008; Knoke Reference Knoke1981]. In contrast, Ebaugh [Reference Ebaugh1977] found that Catholic orders which retained more central control in basic decision-making experienced a lower level of exodus [see also Kanter Reference Kanter1972]. Some sociological work on monasteries touches upon how they are managed, but focuses primarily on the abbatial position. For example, Cregård [Reference Cregård, Rombach and Ohlsson2013] discussed the abbatial position as characterized by maintenance of an existing order, and described how superiors are elected in the small Birgitta order of nuns. In an extensive study of French and Belgian monk monasteries, Hervieu-Léger [Reference Hervieu-Léger2017] analyzed how shifting theological interpretations have affected the role of the abbot. Hervieu-Léger [Reference Hervieu-Léger2017: 167ff.] also noted that there is a “democratization” of monasteries, but did not discuss what this implies in any detail. In a much less recent study, Hillery [Reference Hillery1969] pointed out important organizational differences between monasteries and coercive types of total institutions, but did not address the issue of decision-making.

By investigating communities within one of the strictest monastic orders of the Catholic Church from the point of view of opportunities for voice and exit, this article adds to the sparse knowledge on the politics of total institutions in general, and on decision-making procedures in particular. At the same time, it brings a new, extreme case to the purview of discussions on exit and voice. Addressing the opportunities for monastic members to enter into political dialogue is a way of gaining understanding of the political structure of this type of voluntary total institution [cf. Barry Reference Barry1974] and in what sense it can be seen as “democratized.” In addition to the analysis of the political structure as such, the article considers what members expect in relation to this structure, thereby capturing total institutional life also from the member perspective.

In the analysis, I show how the first stages of monastic membership are characterized by a lack of voice, whereas full membership entails participation in decision-making and discussions of monastic affairs. Yet there are differences in superiors’ decision-making styles, occasionally conflicting with the subordinate members’ expectations of influence. Perhaps surprisingly given ideas of total institutions as authoritarian, (voluntary) total institutional conditions provide incitements for political participation, counteracting monastic promises to abandon will.

Forms of Exit and Voice

From the perspective of exit and voice, we would expect voice to play an important role in monasteries. This is because exit is available only as an option of principle; it is not intended to be used in practice. When the exit option is unavailable, the only way to communicate dissatisfaction is with voice, so that “the role of voice would increase as the opportunities for exit decline” [Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970: 34]. Voice is also related to loyalty. Loyalty is a contingency that shapes whether people exit or voice: members with higher loyalty are more likely to stay and fight rather than leave [Dowding et al. 2000]. Entry costs and ideological attachments further heighten the likelihood of choosing voice over exit [Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970]. Yet voice does not eliminate exit, although it may temporarily delay it [Barry Reference Barry1974; Pfaff and Kim Reference Pfaff and Kim2003].

In Hirschman’s work, dissatisfaction is the underlying reason for a member to consider exit or voice [cf. John Reference John2017]. This article investigates voice from a broader perspective by considering opportunities for voice as a question of democratic procedures [cf. Barakso and Schaffner Reference Barakso and Schaffner2008], rather than as only an expression of displeasure or grievance. Democracy is concerned with including those who are potentially affected by collective decisions in the making of those decisions [e.g. Warren Reference Warren2011]. Collective decisions presuppose a political conversation of some kind. Without entering into the details of the extensive discussions on inclusion in democratic research [e.g. Beckman Reference Beckman2009; Dahl Reference Dahl1989], an important distinction concerns how people enter into this political conversation and what happens in that conversation [cf. Warren Reference Warren2011]. In other words, the opportunity to give one’s opinion is one thing; if it influences decision-making, it is something quite different.

Decision-making based on votes, where everyone affected by the decision has the right to participate, is the ultimate form of democratic voice. I will also consider other forms. Inspired by Teorell’s [Reference Teorell1998] analysis of intraparty decision-making, I suggest a classification of opportunities for voice into probing and anchoring, according to the role these forms of voice have in decision-making: probing refers to openly inviting members to offer their opinions during decision-making whereas anchoring is a way of entrenching a decision that is already about to be made. Probing and anchoring are types of vertical voice [cf. O’Donnell Reference Foxley, Mcpherson and O’donnell1986], and they indicate to what extent the voice of members is ignored or acknowledged and, thus, whether the decision-making style is autarchic or attentive [cf. Warren Reference Warren2011].

In the literature, exit is often defined in different ways depending on the context, for example moving [e.g. van Vugt et al. 2003], quitting a specific job [e.g. Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2006], or leaving for specific options [Whitford and Lee Reference Whitford and Lee2014]. Dowding and John’s [Reference Dowding and John2012] typology of four different forms of exit is developed in relation to services provided by the public sector, but has broader relevance in a modified form. More specifically, the distinction between complete exit (exiting altogether from a given service) and internal exit (from one provider in the public sector to another) also applies in the monastic context.Footnote 2 This is because a monastic order often includes several communities. The question whether monastic members have both a complete exit option (leaving the monastic order all together) and an internal exit option (moving to a different community within the same order) is significant because it determines whether or not monastic communities can be considered as monopolies. This, in turn, is likely to affect how members use their opportunities for voice, and what effects they have.

In the following, I apply the concepts of voice and exit presented above to analyze how monastic collective decision-making is organized and what forms of exit are available. Not least given the vows of obedience and stability, it is also intriguing to consider monks’ and nuns’ expectations and practices related to voice. Barakso and Schaffner [Reference Barakso and Schaffner2008] argue that there are more democratic procedures available when members face barriers to exiting. The vow of stability is a promise to stay regardless of what happens, whereas the vow of obedience implies control of any desire for voice. I argue that monastic batch living, in fact, obstructs the latter promise. Because members live together, perform many daily activities together in a highly scheduled manner, and mutually depend on the products they produce and sell for survival [e.g. Jonveaux 2011], many decisions concerning their livelihood affect them all. In other words, monastic community decisions have great salience for their members and this typically tends to provide incitements to political participation [cf. Franklin Reference Franklin, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996]. Under such conditions, it is unlikely that members would succeed in maintaining constant indifference relative to and acceptance of every decision-making issue, regardless of their promises to the contrary.

Methodological Considerations: Case Selection,Data Collection and Analysis

This article is based on material collected within a qualitative study of Catholic monasteries as total institutions, focusing on social relations within monasteries and the organization of monastic life more generally. Because of the interest in monasteries as total institutions, the limitation to a cloistered, contemplative order is a given. The Cistercian Order was founded in 1098, but divided into two orders in 1892. Cistercians of the Common Observance remained loyal to the original form, whereas the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO), commonly known as Trappists, detached itself to follow the Rule of Saint Benedict more strictly. Nowadays, OCSO is a larger order than the Order of Common Observance, and variations between individual communities can be greater than differences between the orders. Regarding the topic of the present analysis, the orders are sufficiently similar to be dealt with as one case. However, due to decisions taken along the way, the analysis is primarily based on material relating to the OCSO.

In a preparatory study, I stayed for about one week in the guesthouses of one French OCSO-monastery for nuns and one French monastery for monks within the Cistercian Order of Common Observance. I interviewed two monks and one nun during these visits, and took notes during the interviews. I also interviewed one monk in a different monastery within the Cistercian Order of Common Observance. By coincidence, I heard of a former monk, who had spent 10 years in the same monastery, whom I also interviewed.Footnote 3 These interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Based on this preparatory work, I decided to focus on OCSO in France. There are currently 178 OCSO monasteries in the world of which more than half (92) are situated in Europe. France is the country with the largest population of OCSO-communities (27). Focusing on one country facilitated selection and access: at the national level, superiors are in regular contact and were able to share useful information and offer helpful recommendations regarding other communities. The choice of France maximized available options along this principle.

The final design is the result of a step-wise choice of communities to contact. Consequently, I stayed in the guesthouses of one large nun monastery, one average-sized nun monastery, and two average-sized monk monasteries (the average number of members in French monk monasteries is 24, and 26 for French nun monasteries.) All the visits lasted for almost a week each, and I visited the large nun monastery four times. At all but one of my monastic visits, I stayed at the monastic guesthouse and focused primarily on the interviews. This resulted in interviews with 20 nuns (between 35 and 87 years of age, and with 8 to 68 years of experience in Cistercian monastic life) and 15 monks (between 39 and 78 years of age, and with 9 to 51 years of experience in Cistercian monastic life). The interviews lasted between 45 and 120 minutes, and they were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The members held different positions and were involved in various types of work in the monastery.Footnote 4 Five of the interviewed members were former superiors. At least eight were or had been novice directors (responsible for the education of new members). Six entered before or during the Second Vatican Council. For the pool of interviews to contain experiences of different communities, I also specifically asked for, and interviewed, members who had been living in or spent time in other monasteries.Footnote 5 The interviews were semi-structured, including questions on entrance, exit, work, decision-making and community discussions, relations with other members, relations with the superior, and contacts with outsiders.

Surprisingly, superiors feel they receive too many requests from photographers, documentarists, and social scientists. My study was accepted because I promised anonymity and because superiors expressed their appreciation of my visit and recommended that other superiors accept my request. It is also likely that my personal characteristics played a role. Making the effort to travel from Sweden to remotely situated communities in France and to conduct interviews in a foreign language appear to have signaled my sincere interest, as did the assertion that my goal was to “understand” rather than to “criticize”. It is also notable that my own religious affiliation was never brought up during “negotiations” with the superiors. Although less than a handful of members asked me about this during the interviews (to which I replied that I was a non-practicing Protestant), it was primarily to probe my knowledge of Catholicism, rather than to ascertain my faith.

As a woman, I was not able to stay within the cloistered spaces of a monk monastery. However, during a visit to the large nun monastery, I stayed for four days within the community. I slept in their dormitory and joined the community in all activities (meals, work, offices, meetings, etc.), from the first office in the morning until the last at night. Cistercians gather seven times in church each day for the Liturgy of the Hours, including the offices of Vigils, Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. Throughout my fieldwork, I attended 94 such offices. Although the silent atmosphere of monasteries significantly reduces opportunities for the informal chats that are typical ingredients of ethnographic research, staying at the monastic guesthouses enabled me to talk to other guests, who were often relatives of the members. This provided valuable information and “gossip” about the communities which helped and supported the selection of communities to visit.

Because of the vow of obedience, regulations in the Rule of Saint Benedict, and a preconception of monks and nuns as submissive, members’ interest in voice struck me by surprise at first. Greater awareness of variations also grew from broad, initial coding work of interview transcripts and fieldnotes in N-Vivo, conducted along with the data collection process. The preliminary coding work aimed at identifying fruitful themes and specifying ideas to investigate further, one of which was the “politics of monasteries”. To capture this aspect, I became increasingly attentive to and asked more explicit questions about decision-making and opportunities for discussion in subsequent interviews. I performed a more detailed thematic coding after data collection was complete, including revision of the original codes [cf. Boyatzis Reference Boyatzis1998]. The analysis of this article is thus based on codes relating to membership (e.g. entry, voting for membership, exit) and decision-making (e.g. dialogue, leadership), which I have connected to the conceptualizations of voice and exit described above. I have also systematically studied what the 40 interviewees reported on entry and exits (reasons and numbers), even though this provides only a rough idea rather than precise information. Regarding the themes discussed in this article, the conditions for nuns and monks are relatively similar. I therefore did not perform any cross-comparisons based on gender.

I studied documents such as the Rule of Saint Benedict and the Constitutions of the Order, books on Cistercian spirituality, and webpages of individual communities (primarily in France, the United States, and Ireland). The webpage of the Order provides member statistics from 2009, including information about absentees and different categories of members (e.g. novices, professed members) in each community. I refer to such statistics where they are informative, but have not used them for quantitative analysis.Footnote 6

The issues I discuss here are sensitive from a general monastic perspective. I have been careful to protect the identity of quoted members and only specify gender (nun or monk), except when quoting superiors. Precisely because of their position of power, revealing their standpoints is a less sensitive matter, and their position cannot be ignored when interpreting their accounts. Interviewees, and their monastic affiliation (M1-M7), are identified consistently with randomly assigned numbers (e.g. M1-1, M2-3). I have translated any quotations used from French. When referring to the constitutions, I refer to both the Constitution for monks and the Constitution for nuns, which contain identical paragraphs regarding the matters discussed here.

Entering a Monastery

Within the Cistercian tradition, the primary purpose of monastic membership is to deepen members’ relationship with Christ, within the context of a monastic community with a common purpose and a common vision. Entering a monastery is supposed to be the starting point of a journey of conversion. It involves growing out of a life centred on the ego, moving to a life centred on Christ, and living the monastic life in all its aspects, as described by the Rule of Saint Benedict and the Constitutions of the Order. Membership is a stepwise process. As such, in order to understand opportunities for exit and voice in monasteries, it is imperative to distinguish between the conditions during the extended and stepwise entry process, on the one hand, and the situation for full, “professed” members, on the other.Footnote 7

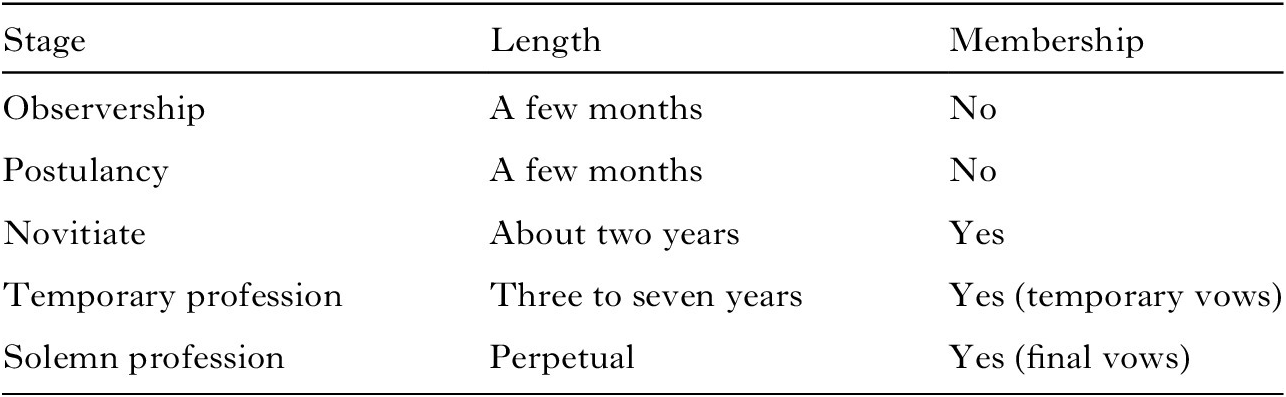

The table below (Table 1) summarizes the different stages of entry, their typical length, and the way in which they are categorized in relation to membership.

Table 1. Stages of entry, typical length and membership.

How should the organizational “people processing” of monasteries be characterized [cf. Van Maanen 1978]? Monastic socialization is formal in the sense that it takes place in segregation from the rest of the community until temporary vows are made. Before this stage, aspiring members and novices live isolated from the rest of the community, study individually and have regular meetings with the novice director. Yet they also perform various types of manual work in the community, albeit on a more rotating basis than full members.

According to OCSO, the total number of members has decreased by 20% since 1940.Footnote 8 A very limited number of persons show interest in entering French Cistercian communities today, and only a selection of those stay throughout the entire entry process. On the basis of the members I interviewed, a rough estimation is that about half of those who enter leave before becoming a full member. Although members express their concerns as to how the decline in membership threatens their community’s survival, it is difficult to combine active recruitment attempts with a view of monastic life as a calling. Some responses are nevertheless noteworthy. For example, many monasteries organize retreats to attract new members. In addition, I met several monks who entered when they were over 40 years old, showing that the previous age limit is no longer applied [see also Dalpiaz 2014: 41]. This is not to say that it is only up to the individual to decide whether or not to stay. Before their temporary profession, the novice director and the superior decide whether or not to permission to continue the process. Although there are fixed stages with a maximum length each, the stepwise process is variable, as the move to the next step depends on individual progress [cf. van Maanen 1978: 28]. For example, a temporary professed member can be prevented from making final vows if not considered “ready.”

The primary question asked during “discernment” is whether candidates have the “right vocation”, that is whether they have the desire to search and deepen their personal relationship with God.Footnote 9 In practice, this is something for the novice director to determine during conversations. It is relatively common that superiors or novice directors ask candidates to leave. For example, the abbess (M4-1) of one monastery said: “It has happened that I’m obliged to say to someone ‘you can’t [stay]. You can’t. Because you have this weakness, or… it’s that thing you can’t accept in our life so it is better if you leave.’” Candidates with psychological problems that make them “unfit” for community life are consistently refused [see also Hillery Reference Hillery1969: 145], and conflictual collaboration with other members may also lead to a candidate being advised to end the process towards full membership. Despite the fact that candidates remain mostly separate from the remaining community until simple profession, some limited informal socialization nevertheless occurs through their work with the other members [cf. van Maanen 1978: 22, 27]. If this does not succeed, it is likely that the candidate will leave. More generally, it is essential that candidates accept the way in which work and education are organized. As stated by the abbess (M4-1) quoted above, they must “enter into what is demanded.” During the entry process, it is essential to “learn to obey.” Some critical questions are accepted, but “if one is really always in opposition, open opposition, with authority, well it’s not possible that she stays,” to quote another abbess (M2-3). To become members, the candidates must demonstrate an ability to quell their voices because they are excluded from participation in collective decision-making until they reach full membership. In other words, during the process towards full membership, there is no opportunity to voice, but only to exit. This possibly leads to a selection of relatively more silent full members than would have been the case otherwise. At the same time, full members have many more opportunities for voice than during the previous stages. Consequently, it is not clear that they continue to suppress their voices.

Monastic Politics

The daily life in a total institution is tightly scheduled, but established routines are insufficient for total institutions to work in the long run. While the Rule of Saint Benedict, the precept according to which Cistercians (and Benedictines) live, and the Constitutions of the Order, present the major guidelines for Cistercian monastic life, monastic communities also need extensive management precisely because they are places of both residence and work. Communities need to deal with how to make use of their buildings and land, how to renovate or rebuild to adapt to a shrinking membership, what production work to pursue and how to organize it. These are but a few general examples of the issues that require a great deal of time and effort in the monasteries I visited. In this article, the central question is how such issues are decided upon.

Although the Second Vatican Council brought with it changes in the interpretation of the vows to place less emphasis on authority and more on dialogue and communication, it is notable that counselling is already mentioned in the Rule of Saint Benedict. Written by Benedict of Nursia in the 6th century, members acknowledge that parts of the Rule are outdated (e.g. Chapter 59 on offering children to the monastery). Nevertheless, the Rule remains a central reference point: every day, each monastic community listens to a reading of a chapter aloud. According to the third chapter of the Rule, the superior should call the members for counsel: “As often as anything important is to be done in the monastery, the abbot shall call the whole community together and himself explain what the business is; and after hearing the advice of the brothers, let him ponder it and follow what he judges the wiser course” [see Fry 1981: 11]. Striving for humility, the member should accept the decision with “unhesitating obedience,”

which comes naturally to those who cherish Christ above all. […] Such people as these immediately put aside their own concerns, [and] abandon their own will. They no longer live by their own judgment, giving in to their whims and appetites; rather they walk according to another’s decisions and directions, choosing to live in monasteries and to have an abbot over them. [Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 5, see e.g. Fry 1981: 14f.]

The Rule of Saint Benedict presents ideals for monastic life but, in this article, I focus on how counseling takes place in practice, what members expect from it, and how they engage in it. In the following, I outline two specific community bodies of importance for decision-making before discussing how superiors are inclined to use community discussions to either probe or anchor on the one hand, and what members expect from and how they participate in such discussions, on the other.

The conventual chapter is comprised of the full members of a community. It makes its decisions on a number of important matters by secret vote. The conventual chapter decides by vote if a novice is to be admitted to continuing to temporary profession or if a junior member is to be admitted to progressing to full membership. However, it is the superior who decides if a novice or a junior member should be presented to the conventual chapter in the first place. The consent of the conventual chapter, on the basis of an absolute majority, is required to admit the novice to temporary profession or the member from temporary to solemn profession. The superior is also elected by the conventual chapter (an absolute majority of votes is required, see C. 39). Only members who have been solemnly professed for at least 7 years and who are at least 35 years old have the right to be elected. Among monks, the abbot (but not the prior) must be a priest. Superiors are usually elected for unrestricted terms but are supposed to tender their own resignations at 75 years of age (C.39, C.40 ST40.A). A less traditional system is based on holding elections every 6 years, but this was not applied in any of the monasteries included in this study.

The conventual chapter decides on significant questions related to infrequent events, whereas the pastoral council (the abbot’s council) is the most important forum for discussions of community projects and everyday practical affairs. In this sense, it is equivalent to a form of executive group.Footnote 10 According to the constitution (ST38.C), the superior should consult the pastoral council in concerns such as the admission of a postulant into the novitiate or the exclusion of a member in temporary vows from making further profession. The council often comprises the prior, the novice director and the cellarer, but any full member could also be included. It is required to consist of at least three members, one of whom is to be elected as a representative by the conventual chapter (C.38, ST.38A). However, the superior does not, in fact, have to follow the recommendation. To what extent superiors do so can be related to their styles of decision-making.

Attentive and Autarchic Decision-Making

Members often highlight the extent to which superiors influence the community, through their practical priorities (e.g. if there is a focus on reorganizing production, rebuilding, or renovating the infrastructure) and their different “personalities.” The personal characteristics often referred to relate to styles of decision-making. I therefore draw upon descriptions of specific superiors to illustrate autarchic and attentive decision-making styles. The point is not to classify superiors per se, although superiors seem to be inclined to one style or the other (at least at a given point in time). Descriptions of superiors are therefore useful for distinguishing between styles of decision-making in communities.

Some superiors are seen as taking decisions more on their own, with little advice from other members. One former superior (M3-3) shared his perception of the situation in certain communities he had visited: “The superior proposes things, not extraordinary things right, propose things, and if someone touches that he, he… he can’t stand it.” Although it is uncertain what the reaction meant precisely, or at what stage of the decision-making process it occurred, it is clear that alternative opinions were not appreciated. In other cases, superiors are perceived as accepting the expression of opposing opinions by members, but they use discussions primarily for anchoring. For example, one monk (M3-2) described decision-making in his community in the following manner:

The abbot, in general, when he has an idea in his head… softly, but firmly… he holds on to it… [laughter] He talks about it with his council which refines it, and afterwards when he speaks of it to the community, in general, it is already something quite developed. Well, there could be modifications, but the things like that, but… but, it’s something quite developed.

Similarly, another monk (M3-5) talked about the same abbot as “he doesn’t say, but you feel that it’s already thought through and all that. And sometimes they [the council] also say ‘well we will do like this’, without asking anything either.” This is a clear example of autarchic decision-making. In fact, the very size of the pastoral council indicates autarchic or attentive decision-making. Some councils only include the superior, the prior, novice director, and an elected member. This signals a more autarchic decision-making style compared to large councils. For example, one former abbess (M2-1) told me that her council was made up of eight members, indicating a more attentive style.

In contrast to the autarchic decision-making style, some superiors are described as “listening” and “accommodating”. One nun (M2-11) described how a former superior, whom she greatly appreciated, led an extensive community discussion with “lots of flexibility, lots of discretion, lots of comprehension, lots of… she listened to us, she listened to us, without immediately telling us ‘well, no, one can’t do it like that, one can’t do it like that.’” This can be referred to as attentive decision-making style, characterized by probing. Probing can take place through discussions, but also in other ways. For example, the abbess of one community requested all members to hand in written suggestions about what to do with a large space that became empty after renovations, before making any decisions. In another monastery, members emphasized the importance of reconciling leadership in order to reduce conflicts. One of the members (M1-2) of this monastery said that the community “had too many dominant elements and so, one couldn’t put someone on top of the others. That would have created… dysfunction. What we had to have was rather someone accommodating.” The abbot (M1-1) also related to me his views on why he was chosen:

I manage to make the brothers live in peace. Whereas if it had been someone with a strong temperament that would have become abbot, I think that for the others, who also have strong temperaments, it would have been difficult. Perhaps they would not have stayed here.

Two points are important in relation to this quotation. First, given the fear of conflicts, it appears that the abbot expected certain members to have problems with a stronger leadership, suggesting they cared about the influence of their voice. Second, the severity of anticipated conflicts between an abbot with a “strong temperament” and members with similar characters was so accentuated that the abbot perceived the risk of exits. In the following, I address the topic of member involvement before turning to the opportunities for exit available to members in general, and how expectations on voice relate to these in particular.

Expectations of Influence

In the sections above, I have described the opportunities for voice that members have, given decision-making bodies and styles. What expectations do individual members have on participation and influence? Considering the vow of obedience and how full members have been socialized into silence during the entry phase, the will to express one’s opinion is surprisingly apparent, although with considerable variation. I will demonstrate these conclusions in turn. One abbess (M2-3) provides a telling example of nuns’ interest in being part of the pastoral council:

I have those who say to me “yes, I would really like to be part of the council too.” […] there are those who find that it’s always the young ones who have the positions of responsibility. Others come to me to say that it’s always those who have studied. Others come to me to say it’s always the senior members. [laughter] […] Thus I tell myself that it proves that it’s a bit of everything because everyone comes to tell me, to complain… but it means that “I would like to be there” [in the council]. That’s what one has to understand.

The abbess experienced that “everyone” came to “complain” about the composition of the council and that some nuns even volunteered to be included. Several nuns also complained about instances where they felt that the abbess listened more to certain (other) nuns than others (themselves). For example, one nun (M2-12) claimed that a former abbess had been “under the influence” of a certain nun and “listened too much to” her; it was clear from the nun’s account that she was upset and angry about how these “strategic whispers” [cf. Serafin Reference Serafin2016: 273] affected decision-making. Another nun (M2-9) summarized her thoughts about the risk of competition for influence in monastic communities by saying that “even a monastery is a small political ensemble.” The central question here is not why some are more influential than others, and who those members are, but that there seems to be such a great interest in having one’s voice heard and participating in and influencing decision-making.

The interview material includes many stories of vivid community discussions on various topics, for example, how to make use of building space, what production work to maintain, or adjusting the precise time of the Liturgy of the Hours. One prior (M3-4) recounted a dialogue on the renovation of the car entrance to the monastic grounds:

Between brothers who want an entry which is completely closed […] and a brother who is the opposite, “no, no, the door has to be open because, well, so that it circulates”… Between completely closed and completely open… one has made a choice.

The monk also emphasized the importance of arranging community discussions because “it’s better if there’s trouble before [decision-making], and that this trouble can be expressed in front of the community.” In other words, it was anticipated not only that the monks’ opinions would diverge, but that they would express them, whether the decision had been taken or not. That is quite different, in fact, from what could be expected in a context of “unhesitating obedience.”

The image of frank dialogue must not be exaggerated, however. One monk (M1-8), who entered in the 1990s, pointed out how discussions reflect generational differences.

The elderly, they don’t have the habit to share, to dialogue. It’s not in their culture, it’s more the culture of the younger ones […] when one is asked to do group dialogues, the elderly they don’t know […] and when one asks for their opinion they say, well, “I have nothing to say, I agree with the abbot.”

Members who entered prior to the Second Vatican Council in the mid-1960s were socialized into a much stricter form of community life with a more rigorous insistence on silence regarding both opinions and speech [see also Hervieu-Léger Reference Hervieu-Léger2017]. However, it cannot be established whether the perceived difference is a generational effect, or an age effect where older members are less engaged. The data is not unanimous regarding the present silence of the elderly, however. In fact, during my stay within the cloistered area of a large nun monastery, I attended a meeting that the abbess organized with the elderly nuns precisely because one of them had aggressively complained about certain conditions in front of all other nuns. Inversely, junior members did not necessarily express their support for great opportunities for voice. One monk (M3-4), with less than ten years of experience of monastic life, described how his abbot typically raised issues to discuss when his own agenda for the project was already “well on its way.” He noted that “An abbey is not a democracy… Thank God! It’s not a democracy. […] And the monks are still educated in obedience… one enters a monastery, under a rule, under an abbot. Well, it’s clear.” Two aspects of this monk’s account should be highlighted. First, the monk appeared content with the fact that monasteries are “not democracies.” At the same time, he seemed satisfied with the present situation in his community and therefore had no need to complain (or to exit), [cf. John Reference John2017]. Second, the monk presented the monastic importance of obedience to an abbot as “clear,” although rules are always open to different interpretations. For example, one former monk (M7-2) explained to me how “disappointed” he had been when he was permitted to participate in communal discussions, after having left what he referred to as the “kindergarten” of the novitiate.

When you read the Rule of Saint Benedict, it’s very democratic, it speaks about that the brothers will meet and discuss and so on, but actually […] [in] this monastery, the democratic part of the rule was hardly expressed at all, but it was only the abbot, the abbot, the abbot with a capital A that decided everything and it was very authoritarian and hierarchical.

Based on his reading of the Rule of Saint Benedict, this former member (M7-2) had expected greater opportunities for voice as a full member. He blamed this on the abbot’s autocratic decision-making style.

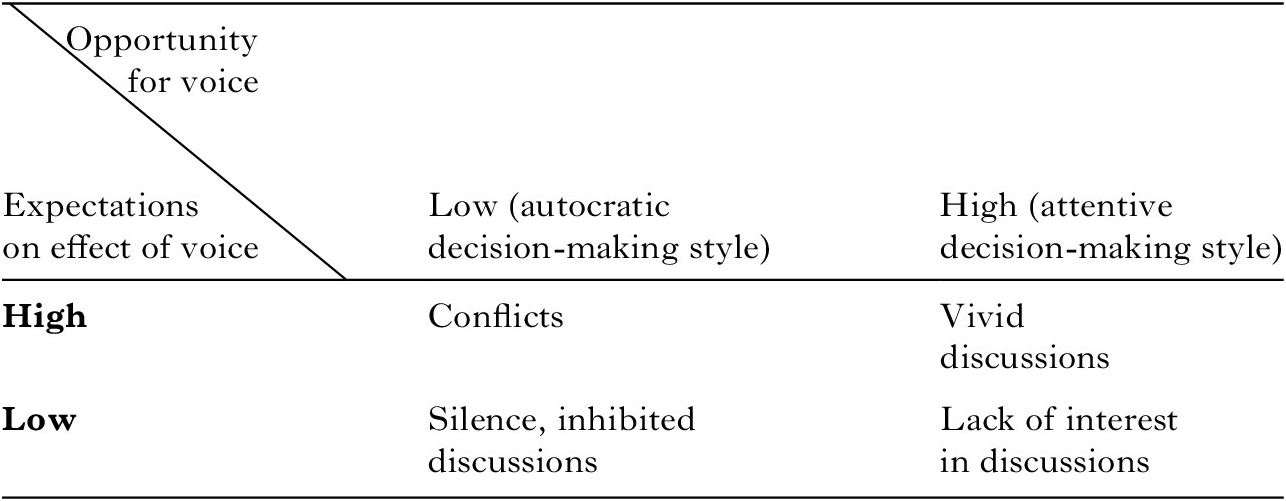

Summing up, there are different expectations on and understanding of what submission to the Rule of Saint Benedict and a superior implies, including the forms of “democracy” prescribed by the Rule. Further study is required to map and explain these differences in more detail. In the present article, this variation is nevertheless significant itself because it indicates potential conflicts between the superior’s decision-making styles and the subaltern members’ expectations, regardless of the fact that they have made the same promises and live according to the same rule. The table below (Table 2) summarizes possible combinations of expectations and opportunities for voice.

Table 2. Opportunities and expectations on voice.

In the section above, examples were provided of both inhibited and vivid discussions. Although unheard of in the communities included in the study, it is, in principle, possible that members become tired of too much discussion or requirements to be involved. This would be an example of the combination of low expectations with attentive decision-making. The combination of greatest interest here, however, is the mismatch between autocratic decision-making style and higher expectations on opportunities for voice, because this is the combination where the risk of conflicts between individual members and the system is highest. Importantly, it is the expectations regarding the effect of a dissenting voice that are most at stake here; those with supporting voices probably care less about having been heard [cf. Pettitt Reference Pettitt2007: 230]. I discuss conflicts in relation to exits below.

Exiting a Monastery, Staying in the Order?

While the exit of candidates in various phases of the entry process (e.g. postulants, novices) is expected and common, the exit of full members is not. For full members, the exit request must be sent to the Holy See (the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome), whereas it is up to the superior to deliberate a member from temporary vows. From a material standpoint, exit costs are lower prior to full membership. Full members renounce the capacity to acquire and possess goods (C.10/C. 55, Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 33) and, in principle, any personal gifts from outsiders (e.g. family) are transferred to the community. (If full members leave, they may receive short-term financial support from the community.) Exit costs are also high because of the social boundaries with the outside world. For example, contact with family members is usually restricted to one visit per year and a very limited number of phone calls. In short, both material and social dependency increases over time, contributing to a high cost of exit. In addition, there is probably also a high emotional cost to breaking what was supposed to be a life-time commitment.

If we take the community level as a reference point rather than the monastic order, and consider full members only, there is also an internal exit option. The vow of stability is a vow to stay in one specific monastery but, in practice, it is possible to move to a different community while remaining a member of the order. Critically, however, such a move has to be admitted by the superior of the monastery where one promised stability. The superior also has the right to oblige a member to transfer temporarily for the sake of peace (C. 60, ST 60.B). For example, one abbess (M2-3) told me that one of the nuns who was currently in her community had been placed “outside” of a previous monastery because she had “not been easy”. Non-stabilized member is the term used for transferred full members who have kept their original membership statute in the new monastery. Non-stabilized members are allowed to participate in community discussions (C.6, ST 6.C) and can be invited to discussion in the pastoral council. After one year in the new community, it is possible for the non-stabilized member to seek consent to change stability, if the new community admits it (C.60: ST 60A).

According to the most recent statistics, 7 out of 12 French nun monasteries and 6 out of 15 French monk monasteries have non-stabilized members. In all of the six monastic communities I visited, I heard of at least one former member who had moved to another community, and interviewed or heard of at least one present, non-stabilized member who originally entered a different community. When talking about the reasons for these moves, “conflicts” emerged as the general theme. Conflicts with the superior have the most severe consequences, and can be tiresome for everyone concerned. One monk (M1-3) mentioned a conflict between the superior and an ordinary member that was not “livable” for anyone else. “In that case, the vow of stability, well, it passes after!” Such difficult situations are dealt with pragmatically, at the expense of spiritual promises. Consequently, the ordinary member is transferred to a different community. It is also notable that the conflict was referred to as a clash of “characters”. This individualized the problem from the point of view of outsiders, in contrast to, for example, signaling a problematic exercise of authority.

From the point of view of subordinates, there are examples of autocratic styles of decision-making that impacted on their decision to leave. One non-stabilized member (M1-9) described his experiences of decision-making in his previous monastery in the following manner:

It’s always the superior who decides, so the others obey, but… it lacks consultation. […] It’s often the superior, or the council, that reflects and afterwards says what one should do, and afterwards the community obeys. And I would also like to be able to give my opinion.

This member would have liked to “give his opinion” and his dissatisfaction was, indeed, partly related to his expectations on voice. He therefore asked his previous superior if he could move, and the superior admitted him to do so. The monk claimed that before he moved, a few fellow members had been of the same opinion about the abbot, but they had not “dared” to talk about it. Although the specific monk I interviewed mentioned these views among the others, it is uncertain how widely spread or known this grievance was within the community. In a different monastery (M7), multiple exits signaled a shared grievance [Pfaff and Kim Reference Pfaff and Kim2003: 408]: the former monk (M7-2) I interviewed told me how unhappy he had been because of how the abbot managed the monastery in terms of deciding everything himself. The monk expressed his displeasure about the monastery to the abbot, and they later discussed the possibility of a “sabbatical year” in some other monastery. However, the decision as to whether the monk would be admitted was delayed, and the monk could no longer endure the situation. After about ten years in the community, he left without permission. Such a dramatic exit is probably exceptional but this former member was, in fact, but one of many monks to exit. According to the former monk (M7-2), the new abbot led to “a really bad atmosphere. He destroyed the whole monastery. […] Several brothers left and then I left the monastery and then additional brothers left.” Regardless of whether the other monks discussed their grievances with the abbot prior to leaving, and to what extent dissatisfaction with opportunities for voice also played a role, it is worth noting that the number of exits probably speaks for itself in terms of signaling some form of shared grievance.

Concluding Remarks

In this article on monastic politics, I have focused on the opportunities for voice available to members, what they expect from these opportunities, and how they engage in them. I have also focused on the opportunities for exit. By definition, everyone is free to enter a voluntary total institution, but there are differences regarding opportunities for exit. For example, the French Foreign Legion, a voluntary total institution of the military kind, is characterized by significant turnover, low exit costs, and limited voice [Sundberg Reference Sundberg2015]. Exit costs from Cistercian monasteries, however, are very high. At the same time, their political structure offers the opportunity for voice. This is an expected combination given previous research on membership in voluntary associations. Given the age of Cistercian monasteries, it also supports the claim that democracy is beneficial for organizational survival [cf. Barakso and Schaffer 2008]. In fact, batch living conditions in monasteries provide incentives for members to care about and engage in decision-making because of its direct relevance for their immediate and extended life situation [cf. Franklin Reference Franklin, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996]. The important conclusion relative to (voluntary) total institutions is thus that a high degree of totality may actually undermine authoritarianism. What is more, total institutions are often associated with an active “underlife,” but this is presumably less common in voluntary total institutions that members have entered to “reinvent” themselves together with like-minded others [Scott Reference Scott2011] and also relatively less important if members can express their grievances through a political system [cf. Davies Reference Davies1989: 93]. Consequently, this article contributes to the understanding of the overt political life of total institutions, in contrast to a more covert underlife.

In a monastic community, all full members have the right to participate in central decision-making on membership and leadership through their votes. Abbatial leadership is a democratic affair regarding elections, but the superior’s exercise of power greatly influences monastic politics by determining whether dialogue is probing or anchoring and, in turn, how ordinary members’ voices impact on decisionmaking. For example, superiors may wrest control in many practical affairs by ensuring that the development of ideas remains in the hands of the pastoral council [cf. Barakso and Schaffer 2008], which the superior ultimately controls by choosing its members. The superiors’ decision-making style therefore crucially affects the level of democratization of the individual monastic communities.

Members hold different expectations regarding their opportunities for voice, and the mismatch between autarchic decision-making and high expectations on the effect of voice leads to conflicts, including exits. Community transfer is a form of internal exit but, unlike internal exit between public services [cf. Dowding and John Reference Dowding and John2012], monastic community shifts cannot be silent. Internal exit is preconditioned by voice because the superior has to admit the transfer. Dowding and John [Reference Dowding and John2012] argue that internal exit is less interesting from a theoretical perspective because internal exit in the public sector does not mean that people take voice with them. Yet the possibility to move to a different monastery is nevertheless of key significance in the monastic setting. First, it means that monastic communities cease to operate as monopolies. In a monopoly, members will mount pressure for improvements to be made. However, if there are alternatives available, it is possible for members to leave, without pushing for change. Second, internal exit is less costly than complete exit, and this democratizes exodus. The possibility of internal exit provides an alternative for subordinates as well as for the superior, however. Admitting dissatisfied members to leave reduces the risk that they express discontent in front of and/or exert a bad influence (from the superior’s perspective) on the other members. Because of the low number of members, however, even a few exits of full members are significant in monastic communities. Admitting internal exit can be a way of removing critique, but several exits, regardless of their type, signal that there is more to the conflict than a “clash of personalities”. Further research could compare voluntary total institutions with or without a monopoly to see how this affects incentives to political participation.

This article focused on opportunities for voice and exit, but I have also made some suggestions as to the way in which variations in opportunities for voice in individual communities affect internal and complete exit. Nevertheless, more research, based on reliable and sufficient statistics for both internal and external exits and sufficient information and operationalization of decision-making styles in individual monasteries, is needed to reach conclusions on exit and voice dynamics in monasteries. Hirschman’s framework has been applied to protest and migration in authoritarian regimes [e.g. Hirschman Reference Hirschman1993; Pfaff and Kim Reference Pfaff and Kim2003], but people are usually born into such regimes. To what extent exit-voice dynamics in voluntary total and/or authoritarian organizations exhibit similar or different patterns remains to be explored.