In 1971, three courts answered the question of whether farmers could press trespass charges against individuals entering the farmers’ privately owned migrant labor camps to provide services to, or document the living conditions of, the migrant workers who lived there. In the first instance, in Michigan a farmer beat up two aid workers who entered his land to provide services to migrant workers and then had them arrested for trespass (Folgueras v. Hassle, 331 F. Supp. 615 (W.D. Mich. 1971)). A second court considered a conflict in New Jersey, where a farmer tried to negotiate with two aid workers—one there to provide medical services and the other legal services. After they refused to offer these services on the farmer’s terms, the farmer pressed trespass charges (State v. Shack, 58 N.J. 297 (1971)). In the third decision, the court considered a test case out of New York in which a reporter tried to access a migrant camp to report on living and working conditions. The prearranged refusal of access and corresponding refusal to leave resulted in his arrest (People v. Rewald, 65 Misc. 2d 453 (N.Y. Cnty. Ct. 1971)). Each trespasser eventually had their convictions overturned.

This article tells the story of what happened before these court cases—the story of charity workers who entered the camps without incident between World War II and the mid-1960s. From the 1940s to the 1960s, farmers welcomed onto their privately owned labor camps the rural women of the Michigan Migrant Ministry, who, like those later labeled trespassers, hoped to provide services to migrant workers. The women created informal safety nets that distributed resources and services such as food, clothing, and childcare to migrant workers who lived in poverty, often without decent shelter or clean water. The resulting informal safety nets were vital to local economic structures and migrant well-being. Yet because the women did not directly challenge local exploitative labor practices or the geographic isolation of migrant workers, the safety nets that they created performed other equally important functions for the settled white rural residents: policing migrant morality, maintaining rural segregation, and performing surveillance of community outsiders.

Experts at all levels of government recognized that the structure of federal, state, and local labor and welfare laws created a contradiction between the economic necessity of migrant labor and the social and legal norms of settled and geographically rooted rural communities that typically provided both formal and informal welfare services to their residents (Goudey c. 1942; State of Michigan 1965). Migrant workers needed informal aid because federal and state laws failed to ensure that even their basic needs were met. Labor laws excluded rural agricultural laborers, focusing instead on forms of work more common in urban areas. These gaps left by national and state labor and welfare laws were traditionally filled in tight-knit rural communities by an informal safety net composed of reciprocal economic and social exchange between close members of the settled farming community. Yet when relying on migrant labor, individual farmers deployed property rights to geographically isolate migrant workers and constrain their access to both the formal welfare system and the informal safety nets common to rural communities that had always filled the gaps left by formal welfare support systems.

Rural communities were left to make the contradiction—between the necessary migrant labor form and the lack of legal and social supports for migrant labor—sustainable in ad hoc ways. The informal welfare systems in rural communities, like those created by the Migrant Ministry, were inseparable from a legal landscape that necessitated their existence and shaped their implementation. The result of this relationship between formal law and informal safety nets was a façade of family farms that concealed the industrial-scale migrant labor force required to sustain Michigan’s agricultural economy (López Reference López1996; Pruitt Reference Pruitt2006). This article therefore looks beyond the rural neighborliness of the Migrant Ministry to the rural norms surrounding race and labor that compounded the effects of inadequate labor laws, private property rights, and the absence of formal safety nets for migrants.

The women of the Migrant Ministry mobilized public displays of charity, supported by both local churches and businesses, to uplift workers and reform their lives toward a white, middle-class, Protestant ideal—much like the Progressive Era reformers before them. Farmers permitted the Migrant Ministry to perform aid work in their camps because the safety nets contributed to a better workforce and allowed farmers to fulfill a moral and paternalistic obligation to their employees. Despite the good intentions of the missionaries, what resulted was a system of rural informal welfare resembling industrial welfare capitalism, sustaining exploitative legal structures. While the intentions of the women of the Migrant Ministry were generous and genuine, and the aid they provided much needed, in effect the safety nets worked with legal structures to help maintain a reliable and subordinated workforce.

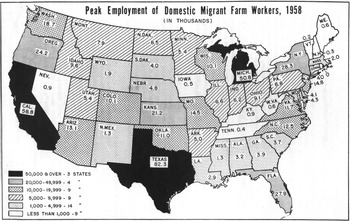

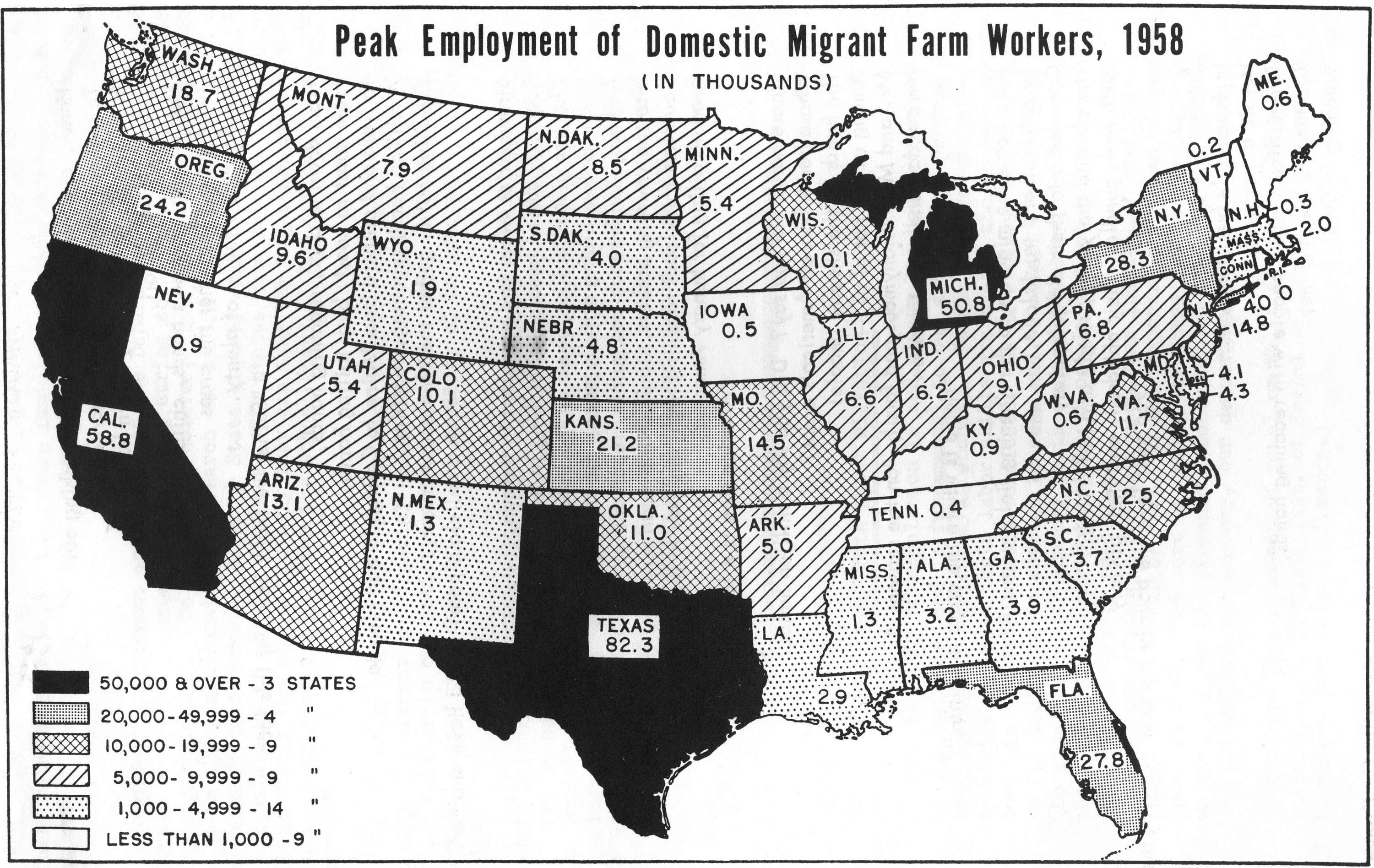

Michigan, in particular, provides an important case study.Footnote 1 During the three decades discussed in this article, more migrant workers labored in the fields of Michigan than in any other state besides California and Texas (Peak Employment of Domestic Farmworkers c. 1958; Michigan Migrant Ministry Annual Report 1961; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 100; Fine Reference Fine2000, 163; Badillo Reference Badillo2003, 38–39). In the 1940s and 1950s, Michigan experienced a boom in its fruit industry that required a massive migrant labor force, including not only Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans from Texas but also African American and white migrant families from the South as well as an in-state migrant stream (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 35–48). The Michigan Migrant Ministry, part of a national organization of state-based Migrant Ministries, actively crafted informal safety nets for dozens of Michigan counties and thousands of laborers, which in turn helped facilitate the temporary and vulnerable, yet stable labor force required by Michigan’s farmers (State of Michigan 1965; Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 6). Thus, the Migrant Ministry records offer a rare opportunity to investigate the formation of informal safety nets in the Midwest across multiple rural communities.

Further, Michigan as a case study contributes to our understanding of the construction of racial and ethnic homogeneity in the rural Midwest (Fink Reference Fink1998, 116). Rural Michiganders took part in the formation of race through participation in informal welfare systems that were intertwined with formal legal structures like the property rights that farmers used to limit access to their lands (López Reference López1996, 147). While the settled rural communities discussed in this article were far from homogenous or nonhierarchical, the conflict I focus on here is between migrant agricultural laborers and the settled community members represented by the church women and growers. In that sense, the article focuses on efforts of many in rural communities to control both access to migrant workers (through formal law including farmers’ property rights) and resource distribution (through the Migrant Ministry’s programs). Rural communities used informal safety nets to shape local racial hierarchies in ways that perpetuated a new definition of rural labor as nonwhite and low-status, while simultaneously maintaining a definition of rural farming communities as monolithically white.

These efforts for control were part of residents’ broader attempt to protect and maintain a specific meaning of belonging and community in a changing rural America (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 9). Informal welfare mitigated against migrant reliance on formal welfare benefits by providing in-kind goods and services and by using exclusionary practices that discouraged incorporation of migrants into the settled community. Together, these effects relieved pressure for systemic legal change.

The first part of this article examines the laws at work in the background shaping the relationship between migrant agricultural laborers and permanent community members in Michigan’s settled rural communities. The second part examines the informal safety nets created by the rural church women. After detailing the Migrant Ministry’s scope and contours, I outline the ways in which the program worked in tandem with formal legal structures to benefit the local economy and construct racial definitions and hierarchies rooted in labor. The third and final part of the article examines how local solutions to the problem of migrant labor shifted from informal welfare systems to the use of formal trespass charges against federally funded farm labor advocates in the late 1960s, culminating in decisions like State v. Shack in 1971.Footnote 2

WORKING AND LIVING ON THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE OF MIGRANT LABOR

On July 23, 1969, Violadelle Valdez and Donald Folgueras drove down a private drive to a migrant agricultural labor camp in rural Michigan to provide aid. That single, private drive led back to thirty-five small wooden cabins that were tucked in dense foliage bordering a swamp. That was “Krohn Camp,” hidden from public view and owned by Joseph Hassle, a large-scale farmer. For his employees who lived there, life was hard. The farm’s crew leader recruited families like the Gutierrezes. With no money to pay for the journey from Texas to Michigan, the Gutierrez family relied on the crew chief to advance them enough money for transportation costs and living expenses. They arrived for work in Michigan already in debt. Families in the camp, like families in all agricultural labor camps, were reliant on the camp owner for access to clean water, toilets and showers, sanitation and sewage treatment, transportation, and access to health care. Farmers—camp owners—rarely adequately supplied even a modicum of these services (Folgueras, 311 F. Supp. at 617; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 180–82).

Valdez and Folgueras were probably nervous as they drove down that private drive on Hassle’s property. They should have been. Folgueras had been forcibly evicted from the property just the day before because he tried to take a water sample. Folgueras, who like Valdez was a student coordinator for the federally funded United Migrants for Opportunity, Inc., would have known that many camps like Krohn Camp did not have clean drinking water. On this day, Valdez made the drive out to Krohn Camp at the request of the Gutierrez family. They had sick children—not uncommon in camps—and they had requested her aid. Maybe because Valdez was frightened to go alone, Folgueras accompanied her. As they drove down the drive, Hassle saw them and followed (Folgueras, 311 F. Supp. at 617; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 180–82).

Hassle went directly for Folgueras when he got out of his vehicle. He probably had his shotgun in hand. He knocked Folgueras to the ground. When Folgueras tried to get up, Hassle hit him to the ground again. As Folgueras grasped for his glasses, Hassle kicked him repeatedly. And there Folgueras lay for two hours, in front of a crowd, pinned down by Hassle’s shotgun until the police arrived (Folgueras, 311 F. Supp. at 617; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 180–82). The two deputy sheriffs spoke to Hassle. They spoke to Folgueras and Valdez. They never spoke with the Gutierrezes. Then, they told Valdez and Folgueras that they should leave. The two outreach workers were unwilling to do so, and the deputy sheriffs arrested them both for criminal trespass (Folgueras, 311 F. Supp. at 617; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 180–82).

Ultimately, Folgueras, Valdez, and the Gutierrezes would successfully seek an injunction and declaratory judgment upholding the “constitutional, statutory, and common law right” of the aid workers to access migrant labor camps on Hassle’s private property, and the right of the Gutierrezes to have them as visitors, in Folgueras v. Hassle in 1971 (331 F. Supp. 615). But aid workers had been seeking access to migrant labor camps for decades before the decision. The following deep dive into the history of the Michigan Migrant Ministry provides a new view of Folgueras and other decisions like it—a view that sees the decisions not as the prerequisites of access to migrant camps but rather as markers of a shift away from a previous period of comparably open access to migrant camps.

In the period before Folgueras, in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, migrant workers like the Gutierrezes traveled across the United States encountering a web of laws that uniquely governed their lives in ways that other types of workers did not experience. This legal landscape took shape by the end of World War II with federal New Deal labor legislation and immigration law as well as postwar state laws made for urban factory workers that purposefully excluded migrant agricultural workers. The effects of these urban-based laws were exacerbated by local residency requirements for welfare benefits, individual contracts between growers and laborers, and prejudice. The landscape of local, state, and federal laws governing the lives and labor of migrants left them vulnerable and forced them to rely on the generosity of informal rural social safety nets.

Nationally, key New Deal labor protections and benefits for industrial workers excluded agricultural workers (Ngai Reference Ngai2004, 136; Farhang and Katznelson Reference Farhang and Katznelson2005; Coppess Reference Coppess2018, 32, 44–45). A well-known example is the Social Security Act, which excluded agricultural workers—even the amendments in 1950 made to include agricultural workers contained requirements that disqualified as many as 95 percent of the Midwest’s migrant laborers (42 U.S.C. §§ 301–1307 (1940); Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 148). Farmworkers were also specifically excluded from the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, preventing them from accessing benefits typical of many urban workers’ collective bargaining agreements such as health insurance and grievance procedures (29 U.S.C. §§ 151–66, 152 (1940); National Advisory Committee on Farm Labor n.d.). Similarly, the Fair Labor Standards Act excluded farm labor (29 U.S.C. §§ 201–19, 213 (1940); Norris Reference Norris2009, 48), but did, under certain conditions, restrict children under sixteen from working in agriculture during school hours (29 U.S.C. §§ 201–19, 212–13 (1940); US Department of Labor, 1960, 15; Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 227). The 1935 Motor Carrier Act regulated the transportation of workers across state lines, including the common practice of transporting dozens of laborers in a single truck designed to haul livestock nearly nonstop from Texas. However, the failure to enforce the law resulted in devastating deaths, including a 1940 accident that killed thirty-one people on their way to Michigan (49 U.S.C. §§ 301–27 (1940); Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 54–57).

Federal immigration policies also helped form an agricultural labor stream from Mexico and a racialized transnational workforce with various legal statuses, including Mexican Americans, legal immigrants, undocumented migrants, and imported foreign contract workers. Between 1942 and 1965, the federal government facilitated the seasonal agricultural labor of Mexican nationals in American farm fields through a program colloquially known as the Bracero Program. Created as an emergency measure during World War II, then sustained through and after the Korean War, the multiple iterations of the program purportedly guaranteed sanitary housing, access to medical care, free and safe transportation, and good wages for male workers (Public Law 45, 57 Stat. 70 (1943); Public Law 78, 65 Stat. 119 (1951); Public Law 82-414, 66 Stat. 163 § 101, 212 (1952); Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. 1101–1503, 1182 (1952); Ngai Reference Ngai2004, 128–29; Cohen Reference Cohen2011, 22). These guarantees were violated in many ways, and those working as braceros experienced, at best, only marginally better working and living conditions than other migrant workers did.Footnote 3 National labor policy and immigration law together created the conditions for a vulnerable rural agricultural labor force (Fine Reference Fine2000, 164–66).

State law and policy further contributed to the poor working conditions of migrant workers in the Midwest (Fine Reference Fine2000, 289, 301). Workers’ compensation, minimum wage, and unemployment insurance were unavailable to migrant workers in rural Michigan (Public Act No. 44 (1965), 63–78; Public Act No. 269 (1966), 383–84; Public Act 234 (1966), 311–12; Public Act No. 160 (1966), 180–81; Public Act No. 283 (1967), 579–80).Footnote 4 State and local housing and sanitation codes either did not exist or were not enforced (Mecosta County Reports 1958; US Department of Labor 1960).Footnote 5 Residency laws, in Michigan and elsewhere, made it impossible for migrant workers to access governmental welfare services or vote (Lenawee County Reports 1962).Footnote 6

Jim Crow laws in Texas and the South similarly worked to push Latinx and African American workers into an exploitative domestic migrant stream. Many Mexican, Mexican American, and African American migrant laborers who traveled to Michigan and the Midwest from the South found better opportunities and wages as they traveled away from even more oppressive conditions (Ngai Reference Ngai2004, 134; Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2011, 6). Some Mexican Americans from Texas described the journey to the Midwest as a metaphor for their arrival at social justice (Limon Reference Limon, Valerio-Jiménez, Vaquera-Vásquez and Fox2017, 51; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 53). African Americans, too, remarked about better opportunities in the North, but in Michigan’s rural communities they continued to experience discrimination more intensely than their Mexican American counterparts. While the law on the books in Texas and the South might have pushed workers of color northward, racial discrimination continued to shape labor conditions in the Midwest (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 104–05; US Department of Labor 1960).

Individual labor contracts further intensified the impact of the larger legal structures: staggered payment and holdback clauses withheld workers’ pay until the season was over, thus preventing migrant workers from seeking better conditions (Ngai Reference Ngai2004, 127–66; Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 79). Contracts contained provisions that placed all risk on the laborers; a common provision voided contracts in the case of crop failure for example (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 155). Labor recruiters made false promises that workers would be given free housing, meals, and transportation. In truth, housing and transportation were often deducted from workers’ pay, and groceries had to be bought at exorbitant prices at local grocery stores where their employer arranged credit for them (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 154–55). In contrast to the itinerant rural farmhands of the early twentieth century, who mirrored the ethnicity of the local community and sealed agreements with a handshake, modern migrant labor after World War II was contract labor performed at an arm’s distance by outsiders (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 76–79, 154–55; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 13–14; Ngai Reference Ngai2004, 130, 133). For workers in Michigan in particular, these laws changed very little between 1942 and 1965, leaving significant gaps in formal legal protections and government services (Fine Reference Fine2000, 163–82).

During each stop along the harvest route, these formal legal structures resulted in physical landscapes of isolated migrant labor camps where migrant laborers experienced exploitation and exclusion, and where they were purposefully disconnected geographically and socially from local settled communities and other labor camps.Footnote 7 Physically concealed and contained in camps far from public roads, most migrants lacked access to the transportation necessary to leave poor working conditions or even travel freely to town for goods and recreation (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 19, 55, 68). The isolated labor camp served as a spatial referent of racial and ethnic otherness for all migrant workers, including dwindling numbers of white workers from the South (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 2, 6, 76, 82–83; Ignatiev Reference Ignatiev1995; Gordon Reference Gordon1999). Farmers created and maintained physically isolated migrant camps, which required Migrant Ministry workers to request permission to enter and enabled farmers to assert private property rights against aid workers like Folgueras and Valdez in the late 1960s (Shack, 58 N.J. at 300; Folgueras, 331 F. Supp. at 619). In important ways, geography affected how legal structures governing migrant labor were experienced on the ground.

In these isolated camps, the working and living conditions of migrant workers were inhumane. Sanitation was substandard; privacy did not exist; medical care was hard to find (Fall Meeting Notes 1941; Ingham County Reports 1954). All plumbing was outdoors, and showers with hot water were rare (Berrien County Reports 1962; Fine Reference Fine2000, 166–67). Toilets, when they were available, were often in disrepair or so close to the water well as to contaminate it (Livingston County Reports 1954). The absence of basic sanitation caused illnesses like diphtheria and dysentery that spread through the camps (Meeting Notes 1943; Session on the Status of Migrant Children 1954; Fine Reference Fine2000, 168).

Migrants lived vulnerable, precarious lives shaped by a set of laws that failed to protect them as workers and families. And still they found space to be active agents in shaping their lives and communities (Anders 2013, 42; Weise Reference Weise2015, 122). They took pride in their occupation and may have crafted positive narratives consistent with those of the church charity workers: narratives of independence, self-sufficiency, and progress (Weise Reference Weise2015, 147). Latinas in particular were agents of change for their families (Delgadillo and Weaver 2017, 239, 243; Limon Reference Limon, Valerio-Jiménez, Vaquera-Vásquez and Fox2017, 49). Beyond the care and canning work they performed, women participated with their communities to celebrate births and mourn deaths (Moralez Reference Moralez2011, 41; Anders 2013, 57). They shared meals, played music, and danced (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 157). Workers brought their own instruments, formed conjuntos, and played Tejano music for friends and family (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 160; Rivas Reference Rivas2003; Limon Reference Limon, Valerio-Jiménez, Vaquera-Vásquez and Fox2017, 49). Those who could bought Detroit-made cars, facilitating community building through visits to other camps or to see those who had settled out of the migrant stream (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 25; Ngai Reference Ngai2004, 133; Norris Reference Norris2009, 57). In ways that mattered, migrant workers actively made their own communities and asserted control over their own lives in small but meaningful ways, even before the farmworkers’ movements of the 1960s (Onion Crop Stands Unpicked in Field 1940; All in Family Help Pick Cucumbers 1952; Anders 2013, 43; Weise Reference Weise2015, 122). And yet the overwhelming truth was that migrants endured oppressive living and working conditions while remaining essential to the livelihood of rural farm communities.

Despite the fact that migrant labor required skilled and swift handling of tools, after World War II perceptions of field labor were shifting from the toil of respectable white men to something that was low-status and performed by people of color. Stoop labor of the beet fields, most likely to be performed by Latinx laborers, was considered “backward” and not a “modern” farming practice in America (Cohen Reference Cohen2011, 6, 9). As the postwar period wore on, American farming became more mechanized. Increasingly it resembled industrial production in scale, as it did with respect to employer–employee relationships (Cohen Reference Cohen2011, 6, 9). White farmers of the Midwest during the post–World War II decades were starting to understand themselves as modern businessmen utilizing mechanization (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 23; Cohen Reference Cohen2011, 47). In no small part, the new organization of farm labor, introduced in the region by the sugar beet industry, helped to change the understanding of just what rural labor was. Farmers were modern employers of employees like urban industrial employers, not yeomen with farmhands who bridged work and communal life (Mapes Reference Mapes2009, 6; Cohen Reference Cohen2011, 54; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2012; Flores Reference Flores2016). While the meaning and sources of rural labor had changed, the laws that governed that labor had not.

The exclusion of agricultural workers from New Deal labor policies was not just characteristic of economic recovery programs of the period, it opened the possibility for the local committees of the Michigan Migrant Ministry to step in. Legal scholars have long argued that restrictive welfare relief policies—like those governing migrant workers—were designed to “reinforce work norms” (Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1993, xv). So too were the informal safety nets created by the rural church women of the Michigan Migrant Ministry. The legal structures that shaped the working and living conditions of migrant laborers in Michigan combined with these informal safety nets to maintain a necessary workforce for Michigan’s farmers. The example of the Migrant Ministry that follows in the next section of the article reveals how informal rural safety nets both provided much-needed assistance and supported social control of migrant laborers.

THE MICHIGAN MIGRANT MINISTRY—A “RESPONSIBILITY TOWARD THE MIGRANT PEOPLE”

The Migrant Ministry began on the East Coast in the early 1930s when “a group of missionary-minded women … saw the need and did something about it among the Negro migrants in the area” (Berrien County Reports 1958; A Background Paper for the Reconsideration of the Goals of the Migrant Ministry n.d.; Hoffman Reference Hoffman1987, 3). The organization spread westward until it found a home in Michigan in 1940. The Protestant women of the Michigan United Church Women, who “saw their responsibility toward the migrant people who were coming into Michigan and acted to meet the challenge,” were the primary organizers and fundraisers behind the Migrant Ministry in the state (Berrien County Reports 1958). The Migrant Ministry organized local volunteers and hired outside missionaries and staffers to coordinate local county-level programs to improve the living conditions of rural migrant workers county by county. Between 1940 and 1965, the program grew into a robust summer religious program for migrant workers, reaching up to 10 to 25 percent of all migrant workers in the state (Michigan Migrant Ministry Annual Reports 1953–1960).

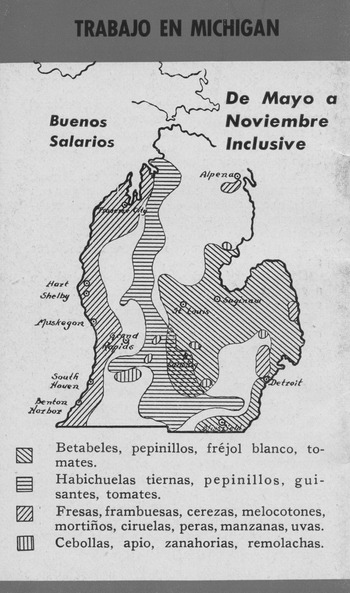

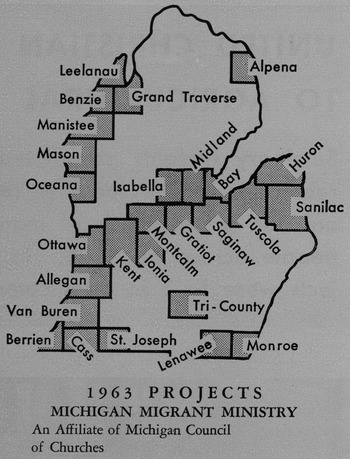

The far-reaching extent of Migrant Ministry programming is illustrated in a comparison of the maps in Figures 3 and 4. The first map is from small booklets for migrant workers showing all regions of agricultural labor in Michigan (Michigan State College 1946a, 1946b). The second map shows each local chapter of the Migrant Ministry in Michigan, demonstrating that the Migrant Ministry reached virtually every county with a significant migrant labor workforce (Michigan Migrant Ministry Pamphlet 1963). The overlap is nearly complete.

FIGURE 1. Peak Employment of Domestic Migrant Farm Workers, 1958.

Source: MFMCC (1958) Courtesy Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

FIGURE 2. Multi-Part Exposé in Detroit Free Press of Migrant Labor in Michigan.

Source: Hansen (1951). Courtesy Detroit Free Press.

FIGURE 3. Map of Harvest Areas in Michigan.

Source: Michigan State College (1946a). Courtesy Archives of Michigan.

FIGURE 4. Map of Michigan Migrant Ministry Projects, 1963.

Source: Michigan Migrant Ministry (1963). Courtesy Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

FIGURE 5. Promotional Image of a Harvester Station-Wagon.

Source: Migrant Millions, n.d. Courtesy Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

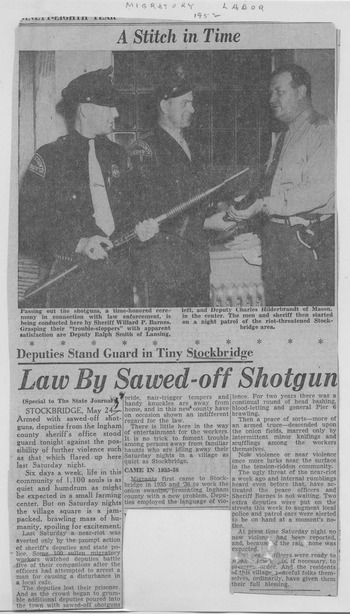

FIGURE 6. Law by Sawed-Off Shotgun in Ingham County, 1952.

Source: The State Journal (1952). Courtesy Lansing State Journal.

The evangelical work of these local women’s groups provided support to migrants and growers by filling gaps in local and state welfare provision. The Michigan Migrant Ministry constructed distinct informal safety nets for migrants traveling through the local community. They provided food for children, clothing, recreation, and aid in times of individual crises. In return for their services, missionaries sought reciprocity from migrant workers in the form of religious conversion or renewals of faith. These acts formed systems of resource distribution that, in tandem with formal law, served less benevolent functions than pure charity. The safety nets distributed resources to migrant laborers in ways that aided grower control and exploitation of labor.Footnote 8 Farmers welcomed the women of the local community onto their privately owned camps and worksites because the women’s evangelism helped maintain a stable, compliant, and controllable workforce.

Structuring Resource Distribution through Ministry Relief Programs

Members of the Migrant Ministry never went into a camp where they had not made previous arrangements with the camp foreman or farmer. Of the many Michigan farmers they contacted—sometimes the majority of farmers in a particular region or community—only a few refused their aid. The same farmers who granted the Migrant Ministry permission denied permission at times to other aid groups wanting to access migrant camps (Montcalm County Reports 1960). While less dramatic than the arrests for trespass in Shack and Folgueras, the requests for, and grants of, permission were powerful exercises of property rights to control access to migrant camps.Footnote 9

Seeking a harvest of souls, the Migrant Ministry staffers used station wagons called Harvesters to follow the physical harvest, bringing ministry to the migrants in the camps as they moved from region to region and crop to crop (Berrien County Reports 1962). The station wagons were equipped “to serve as church, school, library, recreation center” (Meeting Notes 1949; Bay County Reports 1964). Harvester programming included family recreation nights, migrant rest centers, and day cares and bible schools (St. Joseph County Reports 1956; Ottawa County Reports 1958). These three programs together constituted an informal social safety net that caught migrants falling through gaps in formal legal protections and services.

Family Nights

For many local programs, the bulk of the work was spending evenings in the camps for “family nights” (Oceana County Reports 1954).Footnote 10 The Harvesters brought toys, food, clothing, musical instruments, a film projector, and bibles. A typical program might have an hour for sports and recreation, a half hour to screen a film, then a half hour for worship (Sanilac County Reports 1960). The films, mostly in English, ranged in subject from the religious to the secular and offered instruction on everything from health and sanitation to social security benefits (Berrien County Reports 1956; Grand Traverse County Reports 1958; Gratiot County Reports 1960). Following these instructional films, Migrant Ministry staffers gave migrant workers health and parenting pamphlets to study (Marshall Reports 1951; Grand Traverse County Reports 1958).

A primary goal of the Migrant Ministry was “to bring the Christian Gospel to the people in the camps by providing them Christian education, promoting safety and health practices, and wholesome recreation” during family nights (Van Buren County Reports (Keeler) 1962). At the same time, according to the Migrant Ministry, the recreation helped “the worker to understand and respect the needs and rights of his employer” (Michigan Migrant Ministry Pamphlet 1963). One farmer complained to staffers when they requested permission to provide programming in Leelanau County in 1953. He felt that church groups posed a threat to his stable workforce, giving the example of a church group from Detroit that visited his workers the previous year. The day after the church group visited, all of his workers left (Leelanau County Reports 1954). The local Migrant Ministry workers won him over though and proved to him that religious missionary work could be beneficial to him. In 1954, he and other farmers “saw the type of program being carried on [by the Migrant Ministry] and the effect of it on their workers” and “they were happy to have staff workers come” (Leelanau County Reports 1954). The “type of programming” that farmers appreciated included lessons for the migrants about how to maintain and protect the farmers’ property and housing. Migrant Ministry staff claimed as their responsibility the need “to encourage and educate migrant people to take better care of housing and surroundings” (Spring Meeting Notes 1960; Helps for Volunteers c. 1967, 19). In other words, recreation nights educated workers on topics that made them healthier and less costly employees.

Rest and Friendship Centers

By the late 1950s, local projects started running “centers” for migrant workers in nearby farming towns (Grand Traverse County Reports 1958). Centers, like the one in Bay County, might host a rummage sale and have toys for children, comfortable chairs for adults, games, and sewing machines (Bay County Reports 1958). Centers could serve as a parking spot or meeting place for migrants who depended on growers to transport them to and from town (Bay County Reports 1958). Many of the services provided by the centers were free, but some projects encouraged migrants to contribute by providing labor to the Ministry’s projects and activities (Berrien County Reports 1960; Berrien County Reports 1962).

The centers did not focus primarily on religious ministry (Ingham County Reports 1958). Instead, centers like the Mexicano Centro gave young Mexican men a place to gather that was not in the streets or on the sidewalks of towns like Mason, providing them a place to avoid vagrancy arrests and police interactions. The town of Mason sat in the same county as Stockbridge, about twenty miles away, where police officers armed with sawed-off shotguns controlled migrants who entered town on Saturdays. It is no surprise, then, that the 1958 Migrant Ministry report for that county averred that “[m]any in the community were appreciative of the provision of a place to gather for the Nationals, who previously seemed lost in their roaming the streets and hanging around downtown” (Ingham County Reports 1958; US Department of Commerce 1960). Beyond serving as a form of surveillance and containment of the men, lessening reliance on local law enforcement resources, the centers were boons to local merchants, who took advantage of increased numbers of migrants funneled into their small towns. Merchants in rural Michigan frequently exploited the language barrier, marked up the prices of goods, and outright discriminated against migrant workers (Ionia County Reports 1964).

Day Care

Day cares for migrant children performed similar functions to the rest centers. The day cares were often held outside of the camps. Churches would send volunteers to staff the nursery, provide story hour and recreation, and prepare lunch (Lansing Report 1947). Some combined academic instruction with religious worship and teaching (Bay County Reports 1954). They also taught the children “such things as respect for property … [and] cleanliness” (Meeting Notes 1943). Keeping children out of the fields freed their parents from childcare distractions. Although earnest in their desire to help children, the childcare services often seemed to prioritize aid to growers first, then aid to migrant parents and their children (Grand Traverse County Reports 1964). The Migrant Ministry’s quest to provide substitute white Christian parenting for migrant children meant that these children often had far more contact with church women and the local community than did their parents and other adult migrant workers (Badillo Reference Badillo2003, 40; Weise Reference Weise2015, 130–31).

The maternalist efforts of Migrant Ministry volunteers identified migrant children as children who needed to be civilized, converted, educated, and assimilated. On the last day of the day care program, the missionaries sent home “health kits,” which included soap, washcloths, towels, toothbrushes, toothpaste, and combs (Mason County Reports 1962). Health kits, sometimes publicized in the local newspaper, reinforced the stereotype that migrants were dirty (Huron-Tuscola County Reports 1964). At day care, volunteers offended some migrant mothers by bathing the children, assuming, often incorrectly, that they had not been washed before coming to school (Van Buren County Reports (Lacota) 1954; Reul Reference Reul1967, 35).Footnote 11

Migrants, the Migrant Ministry, and the Settled Community

The Migrant Ministry’s mission of shepherding migrants toward a Christian way of life aligned with the farmers’ goal of having a reliable workforce without increasing pay or improving housing conditions. They liked the Migrant Ministry because its programs provided services to migrant workers “which they haven’t time or ability to look after,” wrote one local project organizer (Bay County Reports 1960). The Migrant Ministry supplemented worker income by providing food, cheap goods through thrift sales, and low-cost or free childcare. Despite not having the formality of a government institution, the Ministry’s informal welfare system fit neatly into a larger legal and nonlegal system of labor control. The Migrant Ministry filled health care gaps by providing first aid during family nights, arranging emergency health care services, setting up health clinics, and even giving access to birth control and prenatal care (Meeting Notes 1943; Grand Traverse County Reports 1964; Reference CulpepperCulpepper 1967). These goods and services gave real relief to migrant workers, who could not access the formal welfare system—and to growers, who felt less pressure to improve conditions or provide services themselves.

Migrant workers seem to have genuinely enjoyed the rest and recreational opportunities provided by the Migrant Ministry projects. The games and sporting events arranged by local volunteers, the tape recorders and record players, the films and music used at family nights—all provided welcome opportunities for escape (Grand Traverse County Reports 1958; Ionia County Reports 1962; St. Joseph County Reports 1964; Sanilac County Reports 1964). But migrants also had little choice in recreational opportunities. Isolated on camps, often without cars or independent transportation, they had few opportunities for recreation in segregated rural towns.

By providing a distinct, nongovernmental, religious safety net, the women in the Migrant Ministry used a moral lens to view their own actions and to determine the deservingness of migrant workers—a process that cast migrant workers as outsiders to the settled community. Their supplemental instruction in the English language, Americanization, health, housing upkeep, and moral living all signaled to both migrants and permanent community members that migrants were different from permanent rural residents (Spring Meeting Notes 1960; Ionia County Reports 1962; Michigan Migrant Ministry Pamphlet 1963; Helps for Volunteers c. 1967). Even individual acts of mercy, like driving a father to visit a hospitalized mother and child, were acts of control over migrant mobility (Grand Traverse County Reports 1964). Not only were such kindnesses dependent on Ministry staffers seeing specific individual migrants as especially deserving of their aid, but they were also dependent on farmers giving Migrant Ministry staffers access to migrants living in their camps.Footnote 12

Community members and growers praised local groups for keeping migrants off the streets and out of sight (Ingham County Reports 1958). Rest centers, organized family nights, and day cares all served as opportunities for supervision of the migrant community by the settled rural white community. In the evenings, those who gambled or drank were discouraged by Migrant Ministry volunteers and were offered wholesome alternatives. Migrants who visited community rest centers on the weekend could be supervised in ways they could not if they were in a local bar, restaurant, or pool hall. Not only did rest centers work to maintain segregation in rural public squares, but they also decreased the potential for imprisonment resulting from vagrancy arrests or barroom altercations, keeping workers in the fields (Law by Sawed-Off Shotgun 1952; Ingham County Reports 1958; Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 155).

Gossip was also part of the informal system of resource distribution formed by local Migrant Ministry projects. Scholars of rural law have repeatedly found gossip to be an important form of nonlegal sanction in small communities (Engel Reference Engel1984; Ellickson Reference Ellickson1994; Reference PrifoglePrifogle 2020). Gossip in this case could spread through reports to the state Migrant Committee or local churches who supported local projects. It served as a tool of racial othering and a justification for the structure of resource distribution. The church women who organized and volunteered with the local Migrant Ministry sensationalized the lives of the migrant workers with whom they interacted.

For example, the Lacota Day Care Center report for 1954 noted that women volunteers were concerned about two children with a “Spanish” father and “Northern white” mother. Apparently, according to the report writer, the mother, Mrs. Gutrez, had tried to leave her husband, Frank, because he beat her and because there was a warrant for his arrest. One of the children had been hospitalized repeatedly. When the children stopped attending day care, the women volunteers sought their gossip from Mrs. Washing, “a Negro lady” who was familiar with the family. She was able to inform them that the husband was in jail (Van Buren County Reports (Lacota) 1954).

The story itself had no relevance to the type of information the report was intended to collect or disseminate. It reflected the white church women’s gossip about migrant workers—who, it appears, may not have even been migrant workers, but simply an interracial, formerly migrant, family that had settled in the community permanently. The report, likely read by others within the local church community, does not include any information about how the local volunteers tried to help the family. Rather, I want to suggest, it was sensational gossip that contributed to the broader social construction of racial hierarchies in the community. The gossip shaped a narrative about an interracial couple that associated with African Americans, living in the church women’s community, perhaps permanently. The gossip defined the family as outsiders. Similar stories of gossip—like that about a baby crushed in the fields by a truck or a migrant worker who drank rubbing alcohol for three days—worked to identify faults in migrant workers, who were described as living dangerous, immoral, and uneducated lives, and distracted from the legal structures that made their living conditions possible (Kent County Reports 1962; Isabella County Reports 1964; Lenawee County Reports 1964).

The Migrant Ministry’s encouragement of a moral way of living served the needs of the community and growers—and it made the community feel good about itself. One of the most striking aspects of the reports from local projects was comments about how the project made local church women feel. For example, “It was all very new to our women—but every one seemed so very happy. I have never seen such radiance as I saw on the tired faces of these women as they came back from a camp. The project was a real blessing to the women who took part and I’m sure to the Migrants too” (St. Joseph County Reports 1956 (emphasis added); Huron-Tuscola County Reports 1958). Volunteering with the migrants made the women and their community feel better about themselves, first and foremost (Marshall Reports 1948; Fall Meeting 1955; Ottawa County Reports (Grand Haven) 1964; Weise Reference Weise2015, 162). This feel-good aspect of the missionary work de-emphasized any role the local women may have had in perpetuating the local systems of economic exploitation or segregation.

Still, the women’s gap-filling work was needed by the community because in the postwar period, state legislators, academics, and community members found it difficult to decide just who was “responsible” for migrants’ well-being. A report from the director of Michigan’s Department of Social Welfare stated flatly,

The theory, that the care of non-residents is not a local responsibility, is adhered to in many communities. Thus, if a worker or his family by some misfortune must apply for relief, local antagonism is at once aroused. The public resents this drain on limited local funds by persons whom they believe have no moral or legal right to request help from a community of which they are not an integral part. (Reference GrangerGranger n.d.)

Many government experts sought responsibility for migrant laborers at the local level. One expert told Michigan’s Commission of Migratory Labor that “[c]ommunities need an awakening as to their responsibility” for migrant workers’ needs (Comments Made by Members of Commission of Migratory Labor 1952). The Subcommittee on Health, Welfare, Housing, and Sanitation called on individuals to take personal, if not legal, responsibility: “The grower must depend upon groups of migrant workers to take care of his crops during these short periods of time. Therefore he has, or should have, a personal responsibility for his help” (To Members of the Subcommittee on Health, Welfare, Housing, and Sanitation 1952, 1). Alternatively, rather than alter state welfare residency requirements, state advisors offered another suggestion—divert legal responsibility to the federal government “because of the interstate character of the migrant” (To Members of the Subcommittee on Health, Welfare, Housing, and Sanitation 1952, 4). Or, as a local official in Van Buren County suggested, a voluntary migratory housing code might be “a substitute for possible state action” (Migratory Camp Code Is Adopted 1956). Legislators, policy makers, and local officials all actively avoided formal responsibility for the working and living conditions of migrant laborers.

Thus, with no formal government intervention, the Migrant Ministry was often the first contact for community conflicts, needs, and concerns involving migrant workers.Footnote 13 For example, the chairman of the Grand Traverse County project noted how central the Migrant Ministry was to the community in assisting the migrant workers: “The telephone is often times the righthand of the Migrant Ministry” (Isabella County Reports 1964). Community members would call the chairman late at night to solve community issues related to migrant workers—like when a dozen Mexican Americans were left stranded by their crew leader. The chairman averred that they had received hundreds of these calls from frustrated community members looking for solutions for migrant workers in need (Grand Traverse County Reports 1964).

In Marshall, reports from the late 1940s indicate that the local Migrant Ministry organizers “fully believe the work of the Migrant Committee is a great factor” in the “definite improvement in the class of migrants who come to Marshall” (Marshall Reports 1949). In Mason County, the local organizers thought that their program “played a vital part” in reducing the number of encounters between migrants and local law enforcement for infractions related to drinking, stealing, and family quarrels (Mason County Reports 1960). In short, the Migrant Ministry understood itself, and was understood by the community, as contributing to the peace and prosperity of the settled white rural community.

The local approval for the Migrant Ministry was matched by local disapproval of migrant laborers (Cass County Reports 1962). Reports often included details of “prejudice in the community” (Van Buren County Reports (Central) 1962). One local organizer even wrote, “[p]eople of higher standards of living find many needs and unsolved problems among the migrants in the way of housing, housekeeping aids, etc. But we do not hear the migrants complaining. … We do not feel there are great problems in this area at this time” (Bay County Reports 1964). Staffers in Allegan County wrote in their 1960 report, “[m]igrants must prove themselves worthy of acceptance. Migrants often satisfied to send their children to school in an unpresentable manner” (Allegan County Reports 1960). In Cass County, “[s]ome community people … felt that the migrants spend their money very foolishly, and neglect their family responsibilities” (Cass County Reports 1960). When it came to conflicts between the community and migrant workers—especially Spanish-speaking migrant workers—many believed that “[b]oth groups come in for their share of the blame in this matter” (Meeting Notes 1942).

Many in local communities even feared migrant workers, as did many Migrant Ministry staffers. One report put it like this: “Over the years, the unfavorable stories about irregular migrant behavior have accumulated. Newcomers in the community have always been told these and have developed great fears. Many members of the community regard cherry picking time as one during which to lock all doors, not to walk after dark, and to avoid driving outside the village after dark” (Leelanau County Reports 1960; see also Grand Traverse County Reports 1954). Narratives like these of migrant crime were reflected in informal surveillance efforts in the Migrant Ministry programs and were reinforced by partnerships between local Migrant Ministry organizations and local police departments. For example, in Bay County the Migrant Ministry workers offered translation services to local law enforcement and courts (Bay County Reports 1955; Sanilac County Reports 1955). In Midland County, they even asked the police department to supervise the parties and events they held for migrant families (Midland County Reports 1964).

Some communities, according to the staffers, did have “quite a bit of interest and concern on the part of the community for the migrants” (Grand Traverse County Reports (Traverse City) 1956). For instance, the Traverse City project reported that the Cherry Festival Parade had a float dedicated to the migrants (Grand Traverse County Reports (Traverse City) 1956). In Montcalm County, in 1958, the local Lions Club held a “Fiesta” with the support of the Migrant Ministry. The community celebration allowed migrants and permanent community members to meet and enjoy themselves together (Montcalm County Reports 1958). Similarly, Mason County was proud of its talent show, which included performers from both the migrant camps and settled community as a way of introducing the two communities to each other (Mason County Reports 1960). The theater in the city of Alma also held an “Exchange Cultural Program” in which migrants performed music for the community, and the community was able to “see and to appreciate the Migrant not only as a worker but as a human being” (Gratiot County Reports 1962).

Local volunteers and organizers often made significant differences in individual lives but never made a significant difference in improving the overall working and living conditions for most migrant laborers in their communities. None of the local Migrant Ministry programs challenged the exploitative relationships between the migrant laborers, growers, and local community. Indeed, the informal system of resource distribution functioned alongside and within that larger legal landscape. While the intentions of both out-of-state Migrant Ministry workers and local Migrant Ministry organizers and volunteers were genuinely altruistic, the effects were to legitimate the local economic system that demanded grower control over migrant workers.

The exceptions of cherry parades and fiestas might be read as akin to Progressive Era urban reform efforts, for example. Those reform efforts often utilized public spectacles of charity that gave a false sense of uplift for financial contributors without requiring deep engagement in overturning structural inequities (Huyssen Reference Huyssen2014, 106). The work of the rural church women resembled the charity work of their earlier Progressive Era peers in other ways, as well. They were supported in their efforts by both the church and business interests and acted with the authority of their community. They “inserted themselves into the spaces and lives of overwhelmingly poor and foreign-born populations. Once there, they asserted allegedly superior knowledge of politics, economics, science, and aesthetics to justify remolding those spaces and lives, maintaining or extending political and economic power over them,” just as earlier generations of Progressive Era reformers had (Huyssen Reference Huyssen2014, 14).

This type of uplift performed by the Migrant Ministry also fit well with the web of New Deal labor laws that deliberately excluded migrant agricultural workers. New Deal policies focused on economic recovery and profit accumulation rather than labor protections that might inhibit capitalist growth (Levine Reference Levine1988, 15, 18; Canaday Reference Canaday2009, 124–34). Welfare relief laws, similarly, tended to be “ancillary to economic arrangements … [and] regulate labor” (Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1993, 3, 22). The Migrant Ministry’s safety nets provided essential services to migrant workers in ways that did not challenge these basic legal and policy goals of economic prosperity for farming communities. The Migrant Ministry met the needs of migrant workers in ways that contributed to the maintenance of a ready and compliant agricultural labor force.

All of this looked a lot like welfare capitalism in urban industrial settings, too. Corporate employers before the Great Depression sought ways to provide benefits—better wages, cash dividends, recreational opportunities, vacation—in order to stave off government regulation and union organizing. Many of the company owners who utilized the methods of welfare capitalism also took seriously a moral impulse to fulfill their paternal obligation to their employees (Cohen Reference Cohen1990; Klein Reference Klein2003; Huyssen Reference Huyssen2014, 4–9). Although many narratives of welfare capitalism—like those of Progressive Era reform—place the end of such methods in the New Deal, in rural communities these techniques were alive and well much later. Rural women worked in tandem with farmers and growers, who took pride in the benefit system they created and maintained, both as a moral commitment and as an aid to economic success that resisted government regulation.

Racial Segregation in Rural Michigan and the Migrant Ministry

The charity-based system of welfare capitalism in agriculture not only survived well into midcentury, it also played an integral role in the construction of race in the rural Midwest. Indeed, the rural church women of the Migrant Ministry likely would have found many similarities between their work and older modes of racialized religious charity work. White women missionaries in the nineteenth-century West, for example, were able to garner significant moral, political, and social power for themselves by reforming, converting, civilizing, educating, and assimilating nonwhite and non-Christian women while also benefiting the US government’s project of settler colonialism (Deutsch Reference Deutsch1987, 77, 97; Gordon Reference Gordon1999, 113; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2009, 127; Cahill Reference Cahill2011, 47). While most scholars have found this type of feminine reform work to have ceased by the 1930s, the work of the Michigan Migrant Ministry suggests a much longer legacy. The Migrant Ministry programming reinforced racial boundaries, keeping those workers who settled out of the migrant stream and into the community on the periphery. The safety net created by the Migrant Ministry played an important role in constructing and maintaining racial distinctions in rural communities in the absence of formal segregation.Footnote 14 In Michigan, like elsewhere in the United States, “groups whose job it is to do the worst manual labor of a society are often … racialized as nonwhite—not just because of a vested interest in exploiting them, but also because cognitively race and economic status go hand in hand” (Calavita Reference Calavita2016, 66).

Migrants, particularly migrants of color and especially African American migrants, were discriminated against by local communities, and they had to navigate local systems of segregation. In Blissfield, the “swimming pool is denied to the migrant children” (Lenawee County Reports 1960). Blissfield’s staffers noted that one farmer would not allow “‘white’ people to mix with ‘his’ Negro workers” (Lenawee County Reports 1960).Footnote 15 In Lenawee County, even though the missionaries noted that the “seasonal workers are accepted in all the places in town,” they soon contradicted themselves, further observing that migrant workers had been “refused drinks in a bar” (Lenawee County Reports 1964). Private discrimination was pervasive. Not even the Migrant Ministry program was innocent—some volunteers in the Blissfield area “refused to go to the Negro camps” (Lenawee County Reports 1960). Oceana County did not begin ministering to “these people” until 1964 (Oceana County Reports 1964).Footnote 16

The dissonance found in Migrant Ministry staff reports reveals the complex and disturbing racial understandings of both the missionaries and the wider community. Reports might note for one question that there was no discrimination in the community against migrants but then note instances of discrimination in responses to other questions (Leelanau County Reports 1960). These acts of discrimination were often dismissed as the result of a “few individuals who are prejudiced” in wider communities that were generally accepting of migrant workers (Bay County Reports 1964). That is, the Ministry staffers explained discrimination against migrant workers not as systemic discrimination benefiting the community but as the poor decisions of a few bad apples. They even explained away the lack of community acceptance as a result of local white residents having never interacted with people of color in the past: “it was a surprise for them to see this darker people. They wandered [sic] if they were as human as the white people. … [Now] [t]he local people accept the migrants within limits” (Bay County Reports 1964; St. Joseph County Reports 1964).

Despite the genuine intentions of Migrant Ministry members to help migrants and the very real aid they provided, the large majority of both local-level missionaries and the state committee members of the Michigan Migrant Ministry were unwilling or unable to recognize that the living and working conditions of migrants were the result of systematic, institutional discrimination compounded by an absence of legal protections. To do so would implicate their own complicity in the system.

In Ottawa County, the community feared that migrants might settle out, increasing formal welfare loads and requiring jobs (Ottawa County Reports 1958). That fear would have been compounded when those who settled out were people of color instead of southern white families (Lenawee County Reports 1958). In fact, by 1958 staff reports noted a growing “racial tension” or “unrest” resulting from newly settled local residents of color (Lenawee County Reports 1958). Lack of housing was a key indicator of rural segregation. In 1960, a committee formed in Blissfield for the purpose of improving migrant housing but found “our community realized for the first time that we are not ready or willing to have integration yet” (Lenawee County Reports 1960). Two years later, a report from the Blissfield area noted that the migrants were accepted “really quite well” by the community, except for housing in town, which they “can rarely get” (Lenawee County Reports 1962). “Migrants,” read the report, “can not live where they want to” (Lenawee County Reports 1962). In Montcalm County, “[m]igrants are not allowed to live within the city limits without the prescribed facilities, which are common to all other persons” (Montcalm County Reports 1960). In Lenawee County, “Spanish people are accepted in community life and schools, but housing in the community not willingly opened to them” (Lenawee County Reports 1964). Still, both white migrants and migrants of color settled permanently on the rural fringes in Michigan. Indeed, permanent residence in Michigan was the goal of many (Marshall Reports 1951; Leelanau County Reports 1960; Ionia County Reports 1964).

The local Migrant Ministry committees and white communities often had a difficult time conceptualizing migrant families that settled out of the migrant stream and became permanent members of Michigan’s rural communities (Marshall Reports 1950). Those who settled were “still considered migrants” (Oceana County Reports 1962; see also Montcalm County Reports 1960). The term denoted otherness, rooted in race. In Gratiot County, for instance, the local Migrant Ministry organizers worried that if African Americans settled permanently in the rural community, the local community would have a “silent Mississippi” “situation on [their] hands” (Gratiot County Reports 1962). One report observed that for those who chose to settle in the community, if “they prove themselves to be good citizens they are accepted with mild enthusiasm” (Van Buren County Reports (Central) 1962), but “they are on their own” (Van Buren County Reports (Lacota) 1962).

Again, some variation across local programs is evident. There were examples of the Migrant Ministry in a few communities assisting former migrants to settle into the community as permanent community members (Mecosta County Reports 1958; Berrien County Reports 1960; Oceana County Reports 1964; St. Joseph County Reports 1964). For example, in Bay County, 250 Mexican Americans and 100 African Americans had settled outside of the town limits and were assisted by the Migrant Ministry in painting their homes and improving their toilet facilities (Bay County Reports 1964). But often Migrant Ministry workers were unaware of formerly migrant laborers settling out of the migrant stream into the community. When they were aware, they were frequently unenthusiastic about helping the new community members. For example, in Mason County, the Migrant Ministry reported that they would not work with those who were settling as permanent community members because the local community held favorable attitudes toward the migrants. The report also noted, astonishingly, that the only problem these families faced was a lack of acceptance by the community (Ingham County Reports 1955; Mason County Reports 1964).

One Migrant Ministry staffer observed that the language barrier was to blame for isolation and separation, stating that “proximity does not make for community” (Bay County Reports 1955). Some segregation surely was rooted in the language barrier between English-speaking settled communities and Spanish-speaking migrant communities. Most counties held separate Spanish-language Migrant Ministry “Texas-Mexican” projects distinct from other programming (Oceana County Reports 1954). Others with large Spanish-speaking migrant populations did not attempt to provide programming at all to Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals, citing a lack of Spanish-speaking staff and volunteers as the reason (Allegan County Reports 1960).

But a language barrier could not explain all segregation. A more apt understanding of local rural hierarchies of race is as a field of racial positions, in which white, Latinx, and African American laborers were compared against one another—and others.Footnote 17 Permanent rural white Michiganders, southern white migrants, African Americans, Mexican Americans, Mexican nationals and immigrants, and Native people all occupied different racial positions compared to one another in the structure of rural labor. This comparison of race was a way of constructing and maintaining local racial hierarchies rooted in labor.

For example, one Migrant Ministry report was particularly blunt about the local racial hierarchy: “Spanish speaking people are received very well in [t]he community, better than negro residants [sic]. Most people with whom I have talked like their friendly manner, their lack of aggressiveness, their cleanliness” (Bay County Reports 1960). In Isabella County, the Migrant Ministry focused on assisting young Mexican men who came through the Bracero Program but did not provide aid or programming for the African American laborers in the community (Isabella County Reports 1960). “Acceptance of Mexican better than Negro—but still the attitude of ‘Leave them alone. They don’t want help.’ prevails” (Lenawee County Reports 1960). In fact, Spanish speakers were often more acceptable to the local community than Southern white workers (Oceana County Reports 1964; Van Buren County Reports (Lacota) 1955). One report averred, “except for the language barrier, you wouldn’t know but what they were whites,” referring to Mexican American migrant workers. “In fact, in some instances they might have been treated more courteous” (Tri-County Reports 1964).

These racial constructions not only were observed by Migrant Ministry staffers, but also were integral aspects of Migrant Ministry programming. Berrien County operated two separate Migrant Ministry projects, one for white migrants and one for African American migrants (Berrien County Reports 1956). The program for African Americans began as an “experiment” in the early 1940s with “two young negro youths work[ing] with 1500 negro migrants” (Meeting Notes 1941). The African American program seemed to be at least a partial response to wartime concerns about increased migration of African Americans to Midwestern cities (Meeting Notes 1942). At the same time, Berrien County ran a “White Children’s Center” (Meeting Notes 1942).

Even the African American Migrant Ministry staffers were forced to navigate the rural systems of segregation. Lula Garrett, an African American woman, was assigned to Leelanau County. The committee report (ostensibly written by a white committee member) noted that “She mixed well with all groups, and her usefulness is by no means limited to working with Negro workers” (Leelanau County Reports 1964). In 1951 in Berrien County, an African American Migrant Ministry worker assigned to the local project in Eau Claire had been left for several weeks with no place “that would allow colored people to come inside and eat … and she had to eat cold food or none, there was a self service store that allowed her to wash her hands in the back part of the store before she ate the sandwiches which she prepared herself” (Spring Meeting Notes 1951). The white committee members and state Migrant Ministry officers accepted this situation as given, and “glor[ied] in the steadfast faith which has helped her to see it through” (Spring Meeting Notes 1951). Although the state committee believed that the “racial tensions in the south need our support,” they did not act to dismantle the racial tensions, discrimination, and oppression in their own communities, even for their own missionaries (Spring Meeting Notes 1957).

Migrant Ministry programming implicitly and explicitly accepted and reinforced local modes of segregation—participating in a de facto system of Jim Crow. In doing so, Migrant Ministry organizers framed agricultural labor as nonwhite and migrants as outsiders. Such a framing strengthened the belief that their own rural community was monolithically white and obscured both permanent community members of color and those migrants who, although perhaps only present in the area for a few months of the year, were essential to the community’s well-being. Whiteness, of course, is not a universal experience; it “is contingent, changeable, partial, inconstant, and ultimately social,” and law plays a central role in racial construction in part through establishing the physical geography of social life (López Reference López1996, xiv). Federal, state, and local labor and welfare laws created legal structures that largely preserved the prerogative of farmer employers to deploy property rights in ways that physically and socially isolated migrant laborers to secluded camps. The informal safety nets of the Migrant Ministry worked in tandem with these legal structures to buttress rural racial boundaries and hierarchies. Rural white farming communities were not natural groupings of people but instead communities that deliberately constructed themselves as white through social, physical, and legal boundaries that excluded both temporary community members of color and those who settled on the rural fringe.

CHANGING THE MISSION—“WE ARE AT THE END OF AN ERA”

The Bracero Program ended after the 1964 season, at a time when migrant workers in the Midwest were increasingly Mexican American and Latinx rather than white and African American (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 166, 168; Loza Reference Loza2016, 2). That same year, the federal Economic Opportunity Act provided funding for services supporting migrant workers (42 U.S.C. §§ 2861–62, 2809). In many ways, the change in federal law and policy marked the end of an era of Migrant Ministry programming and rural labor relations more broadly (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 170). In 1962, Cesar Chavez, with Dolores Huerta, formed the National Farm Workers Association, an organization that was soon to become the United Farm Workers. In 1965, the five-year nationwide Delano Grape Strike initiated a new form of activism for migrant agricultural workers.Footnote 18 Migrant workers across the Midwest took direct action and marched, reflecting the influence of the civil rights and Chicano movements (Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2011). For example, in 1967, activists protested farmworker conditions in the March for Migrants by marching from Saginaw to Lansing (Badillo Reference Badillo2003, 41). This section considers how civil rights activism, federal intervention, and even growing secularism within the Migrant Ministry altered both aid to migrant workers and those who provided the aid.

Secularizing the Safety Net

By the 1960s, the staffers who arrived in rural Michigan communities to carry out Migrant Ministry programming were different from those who had arrived in previous decades, and the local communities’ church groups complained (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, x). In Leelanau County, for example, the local organizers were upset that “staff have deliberately avoided any religious discussions,” and gave as an example staffer Barbara Dadd, who was “[a]ll for migrants at expense of residents …Very good social worker, but avoided the spiritual.” The local Migrant Ministry committee had “generally decided that we would like to have staff that are more concerned for the spiritual needs of the migrants[,] … [who] would be primarily interested in these people’s souls” (Leelanau County Reports 1960). By no means was this an unusual example.

Rather than prioritize the religious aspects of the program, which were accepted by, and beneficial to, the local settled community and its economy, staffers in the early 1960s began to prioritize the needs of the local migrant community (Cass County Reports 1962). Previous religious uplift work had adopted a moral lens through which Ministry staffers saw migrant labor. The problem of migrant laborers’ living and working conditions, from a religious or moral perspective, was one that necessitated amelioration of the effects of a natural order. In contrast, staff members who minimized religious uplift seemed to imply that the problem of migrant laborers’ living and working conditions might be the result of systemic, legal, or institutional inequities. Such a perspective would necessitate very different action than mere evangelical uplift, including empowering workers and challenging the local economic structures. This tension between the staffers and the local organizers signaled the staffers’ newfound outsider status as well.

New sources of federal funding further reshaped on-the-ground conditions. For example, federal funding provided an impetus to secularize day care programming for migrant families. Michigan Migrant Opportunity, Inc. (MMOI) formed in 1964 as a collaborative nonprofit between the Michigan Council of Churches and the Michigan Catholic Conference to take advantage of funding from the Economic Opportunity Act. Secular MMOI day cares replaced Migrant Ministry day cares in some communities (MMOI Background and Bylaws n.d.; Gratiot County Reports 1964). Additionally, federal funding provided support for new migrant-outreach organizations, including those like the Southwest Citizens Organization for Poverty Elimination, Camden Regional Legal Services, and United Migrants for Opportunity (Shack 58 N.J. at 300; Folgueras, 331 F. Supp. at 619).

By the mid-1960s, the Michigan Migrant Ministry’s programming was out of step with the rise in social and legal activism nationwide, forcing the Migrant Ministry to change if it was to remain a strong organization. The Migrant Ministry was confronted by migrant workers who were ready for leadership and action (A Background Paper for the Reconsideration of the Goals of the Migrant Ministry n.d.; Michigan Migrant Ministry Annual Report 1969). While the Migrant Ministry had provided an informal safety net for the neediest of migrant workers, and had made a positive impact in some individual migrants’ lives, it had failed as an organization to change, in any meaningful way, the working and living conditions of migrant laborers as a group. Locally and nationally, mere relief was no longer enough. Unions and civil rights advocates demanded structural change (Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 165–93; Badillo Reference Badillo2003, 41; Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2011, 61–93).

The director of the Michigan Migrant Ministry, Mrs. Carl Gladstone, resigned in response to these changes in 1965. Gladstone had been the state director for a decade, shepherding in an expansion of Migrant Ministry county-level programming.Footnote 19 She wrote, “We are at the end of an era and I haven’t the qualifications to put the new thinking and action into the work. I am so concerned for fear social action is going to take precedence over the religious program that has been the core of the Migrant Ministry for many years” (quoted in Valdes Reference Valdes1991, 170). Her concern about shifting away from a religious frame to a reform or activist frame of migrant services reflects precisely the problematic aspects of the safety net created by the Michigan Migrant Ministry projects. Religion had provided local communities with a moralistic frame to separate themselves from their fellow migrant community members and to legitimate local employment practices. The activist frame of the 1960s rebalanced the power structures between missionaries and migrants, focusing on migrant leadership and challenging the exploitation of people of color in rural Michigan.

The Migrant Ministry did change its mission and programming in the late 1960s. A booklet explaining a new program, “Project Friendship,” implicitly recognized the power dynamic inherent in the Migrant Ministry’s past programming, noting that “there is always the danger” in programs “administered by people from the white middle-class churches” “of creating a type of racism in which to be white, middle-class, church-going is to be an acceptable person while to be dark skinned, poor, non-church-going is to be an unacceptable person” (Project Friendship n.d.).

A separate national Migrant Ministry working paper from 1969 went further, suggesting that perhaps the Migrant Ministry had not addressed “real problems so much as … soften[ed] the painful effects of them.” The radical working paper continued,

in this time, it is not enough for us to “look to the interest” of others. This can be manipulative in itself. There are ways of using people even as we believe we serve them. We are called to examine this possibility deeply and carefully. Our ministries to the migrant laborers, as sacrificial as they were on the parts of many; as truly conceived and as sincerely performed as they were in most places; may yet have perpetuated the patterns of exploitation in the most ironical ways. It is this that we must look at in our past (A Background Paper for the Reconsideration of the Goals of the Migrant Ministry n.d. (emphasis added)).

Certainly not all in the Migrant Ministry agreed with the contents of the working paper, which seems to reflect the changes in the perspectives of, and service provided by, the staffers about whom local communities complained. At both an organizational level and at the local level, Migrant Ministry workers, while well-intentioned, “may yet have perpetuated the patterns of exploitation in the most ironical ways” (A Background Paper for the Reconsideration of the Goals of the Migrant Ministry n.d.). The informal social safety nets proved insufficient remedies to the gaps in legal protections and government services because they were never truly meant to be remedies. They were tools of resource distribution that worked in tandem with the laws that necessitated the safety nets.

Informal Resource Distribution to Private Property Rights