Introduction

Energy poverty is a complex, multidimensional issue that has been at the forefront of many policymakers’ minds in recent years due to concerns over ever increasing energy costs. It is sometimes recognised via terms such as ‘fuel poverty’ and ‘energy vulnerability’, which all broadly allude to households being unable to secure materially and socially necessitated levels of energy services in the home (Bouzarovski and Petrova, Reference Bouzarovski and Petrova2015), such as heating, lighting, and use of appliances. Energy poverty is a globally occurring phenomenon (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Silva and Freitas2019; Stojilovska et al., Reference Stojilovska, Yoon and Robert2021; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Day, Ricalde, Brand-Correa, Cedano, Martinez, Santillán, Delgado Triana, Luis Cordova, Milian Gómez, Garcia Torres, Mercado, Castelao Caruana and Pereira2022) that is inherently socially and spatially variable (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lindley and Bouzarovski2019), with vulnerability factors ranging from energy-related needs and practices, and precarity of housing, to welfare and state support, and social networks (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lindley and Bouzarovski2019). The adverse outcomes of energy poverty include worsened physical and mental health (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Snell and Bouzarovski2017), increased absences from school and work (Free et al., Reference Free, Howden-Chapman, Pierse and Viggers2010) and decreased social participation (Stojilovska et al., Reference Stojilovska, Yoon and Robert2021). It is important to distinguish energy poverty from broader issues of income poverty. As Boardman argues, it is “the crucial role of housing stocks – the house, heating system and other energy using equipment” (Boardman, Reference Boardman1991: 221) and “the role of capital investments that distinguishes the fuel poor from the poor” (Boardman, Reference Boardman2010: 256).

Given the significance of energy poverty to human flourishing, it should be a core concern for the social policy discipline, yet to date, it has been relatively marginalised. This is in spite of the fact that energy poverty has been exacerbated in recent years by COVID-19 (Hesselman et al., Reference Hesselman, Varo, Guyet and Thomson2021), and is expected to be compounded further by climate change and associated mitigation policies (Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero, Reference Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero2012). For example, rapidly increasing temperatures in some regions are predicted to shift energy needs from heating to cooling, increasing summer energy consumption, and modifying everyday practices. The use of carbon taxes and levies on electricity bills to fund climate policies could increase energy prices disproportionately, in turn increasing the number of those affected by energy poverty (Okushima, Reference Okushima2019; Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero, Reference Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero2012). More frequent natural disasters and extreme weather conditions impact vulnerable populations in low and middle income countries more heavily, affecting energy security and energy access (Hossain et al., Reference Hossain, Sohel and Ryakitimbo2020; Khan, Reference Khan2019). Climate change will likely create new geographies of energy poverty, making existing vulnerable spaces, such as regions with more extreme climates, and their populations, more vulnerable.

This paper attempts to address this sidelining of energy poverty as a key social policy issue. We start by situating existing knowledge on energy poverty within the discipline, before moving on to an in-depth integrative review of energy poverty and climate change literature across all disciplines. From there, we develop a conceptual framework to study the impacts of climate change on energy poverty, and their relationships with the key pillars of social policy. We end by drawing out key conclusions, and recommendations for the discipline.

Methods

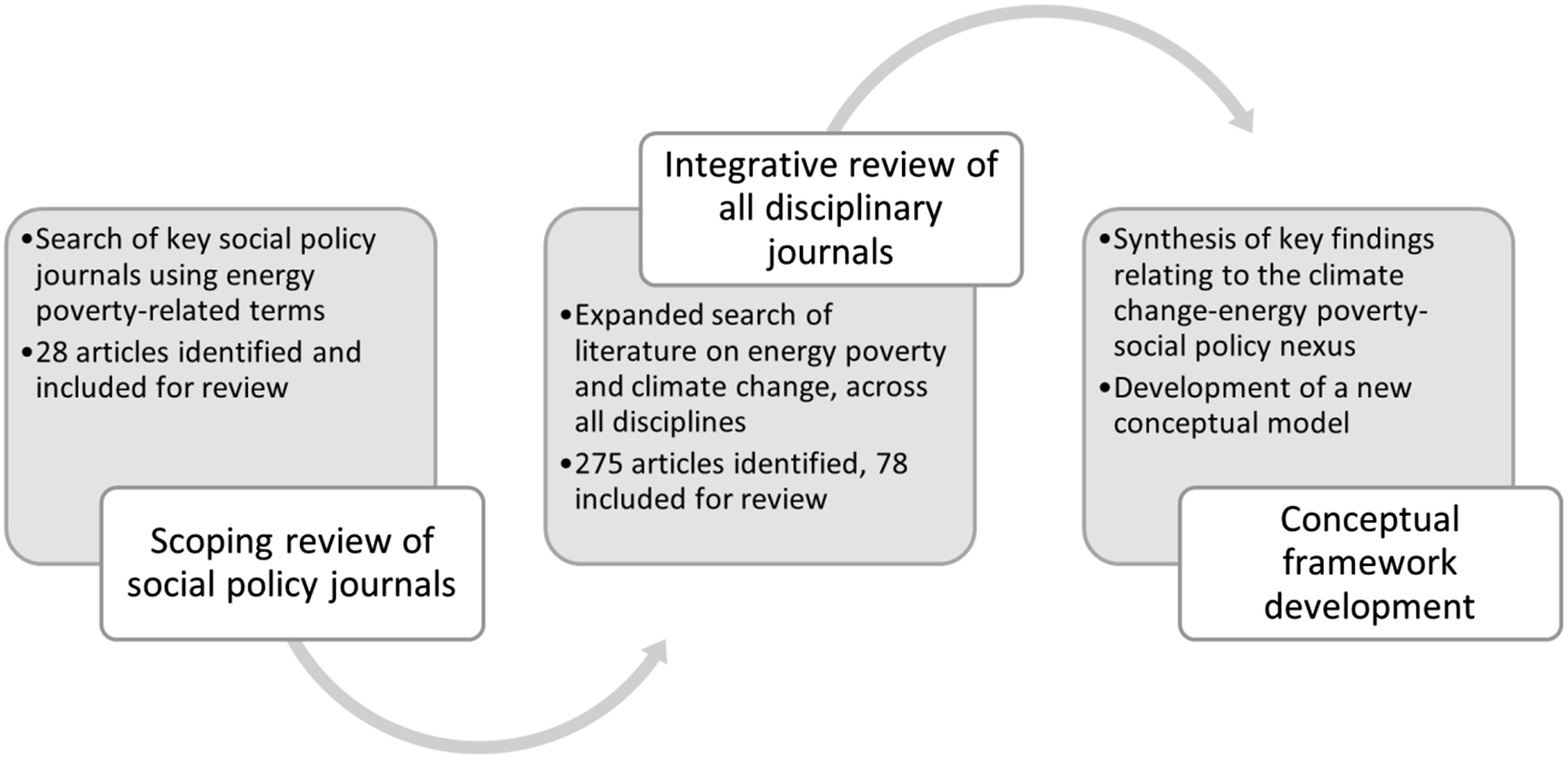

This article emerged from discussions during two participatory online workshops hosted by the Social Policy Association’s Climate Justice and Social Policy group during November–December 2021, held with 100+ social policy scholars, policymakers, and practitioners. Following these events, a two-part research strategy was employed: firstly, a scoping review of key social policy journals to ascertain the nature of existing research on energy poverty in the discipline; and secondly, an in-depth integrative review of literature on energy poverty and climate change, published across all disciplines. The below diagram in Figure 1 visually summarises our research approach, complemented with further detail in the subsections under Methods.

Figure 1. Visual summary of research process

Scoping review of social policy journals

Defining what is ‘social policy’, and thus what counts as a social policy journal, is a difficult and contested task, especially given the interdisciplinary nature of the discipline. It is further compounded by issues previously identified by Powell (Reference Powell2016), who observed “One method is to draw on ISI Journal Citation Reports (JCR) fields…This has been criticized due to ISI’s limited coverage, especially in the social sciences and humanities, e.g. (Harzing and van der Wal, Reference Harzing and van der Wal2008), and is particularly problematic in fields such as social policy, which does not have a JCR field, but is spread over categories such as ‘social issues’, ‘social work’ and ‘public administration’.” (Powell, Reference Powell2016: 652). To overcome this, a scoping search of journals owned by the Social Policy Association, Cambridge University Press, Bristol University Press, SAGE, Wiley, Elsevier, and Emerald Publishing was conducted, resulting in the following twelve journals that are directly concerned with social and public policy:

-

1. Journal of Social Policy

-

2. Social Policy and Society

-

3. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy

-

4. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

-

5. Evidence & Policy

-

6. Policy & Politics

-

7. Global Social Policy

-

8. Critical Social Policy

-

9. Journal of European Social Policy

-

10. Social Policy & Administration

-

11. International Journal of Social Welfare

-

12. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy

This list also incorporates the ‘top’ five social policy journals previously identified by Powell (Reference Powell2016) A search of full manuscript text was conducted in August 2022, using the Scopus database, and the search terms: ‘fuel poor’, ‘fuel poverty’, ‘energy poor’, ‘energy poverty’, ‘energy vulnerability’, and ‘energy vulnerable’. In total, twenty-eight articles were identified, all of which were included for review.

Integrative review of energy poverty and climate change

Literature-based research can be developed through a variety of methods, such as systematic, integrative, and narrative literature reviews (Noble and Smith, Reference Noble and Smith2018). While systematic literature reviews are methodologically rigorous and take a quantitative approach to extract information; in contrast, narrative reviews are identified as an unsystematic, yet flexible method (Noble and Smith, Reference Noble and Smith2018). An integrative literature review is used to synthesise the literature while addressing various research questions in a logical systematic manner, enabling meta-level findings and the building of conceptual frameworks (Ofosu-Peasah et al., Reference Ofosu-Peasah, Ofosu Antwi and Blyth2021). Within this context, the combination of flexibility and rigour of an integrative literature review was considered well-suited for exploring the nexus between energy poverty, climate change, and social policy within the existent academic literature, which includes dealing with non-clear cut issues that could problematise the operation of rigorous criteria as required by systematic literature reviews.

The design of this integrative research was broadly based on the PSALSAR (Protocol- Search- Appraisal- Synthesis- Analysis- Report) framework, used to try to minimise subjectivity (Mengist et al., Reference Mengist, Soromessa and Legese2020). The different steps for the framework are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. PSALSAR framework for this integrative literature review

It is important to acknowledge that by limiting the search terms to the ones above, this research might exclude relevant literature that uses terms like ‘energy access’ or ‘energy insecurity’ to describe similar phenomena, particularly in terms of empirical research in the Global South. Therefore, there are opportunities to expand this research in the future with additional complementary terms, or by comparing how findings change using other search terms. Finally, and also related to limitations, it is important to acknowledge that the exclusion of complete books may result in missed information. However, in many instances resources like books are not accessible, and reviewing them exceeded the team’s resources.

Results

Scoping review of energy poverty research within the discipline of social policy: limited contribution

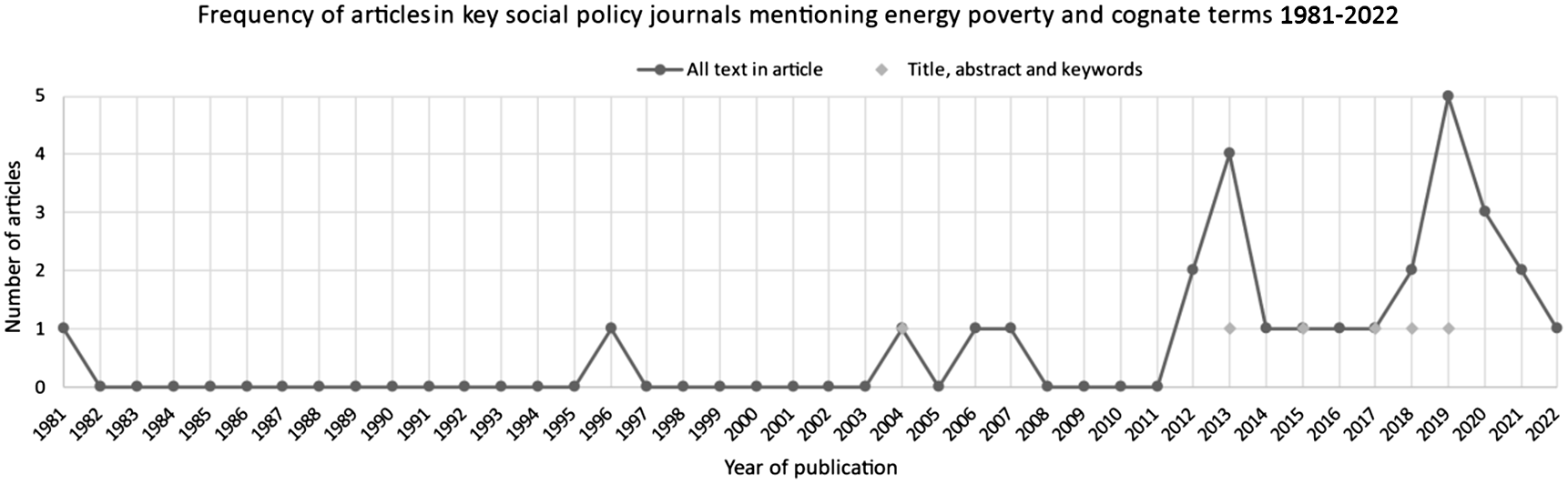

Over the past four decades, just twenty eight articles have been published in social policy journals that mention energy poverty (or cognate terms) at least once across the article. When narrowed to mentions in the title, abstract, and keywords the figure is just six articles, as summarised in Figure 2 below, demonstrating the marginal position of energy poverty within the discipline. Of these twenty eight articles, twenty two focus on one or more of the United Kingdom’s four nations, with a further three articles presenting single country studies of Ireland, Switzerland, and Zimbabwe, two comparative international studies, and one general piece with no geographical anchoring.

Figure 2. Frequency of articles in key social policy journals mentioning energy poverty and cognate terms between 1981-2022

The first mention came from Morrissey and Ditch (Reference Morrissey and Ditch1981), detailing amendments to the controversial 1971 Payments for Debt Act in Northern Ireland, first introduced in response to rent and rate strikes, and later expanded in 1978 to include gas and electricity due to concerns over growing debts and the difficulty for fuel boards to disconnect households as a result of heightened security during the Troubles. Therein followed a long break in publications until 1996 with a passing reference to energy poverty to housing and environment policy in the UK. It was not until 2004 that the first in-depth examination of energy poverty appeared in a social policy journal, with Wright (Reference Wright2004) outlining how government policies were failing older people, and issues of under-heating, narrow eligibility criteria for boiler schemes, and high energy bills. Energy poverty then continues to receive passing, or no mention until Gough (Reference Gough2013) examines the potential for domestic energy policies directed towards fuel poverty to moderate the distributional impact of carbon mitigation policies, via interventions to improve energy efficiency, reduce energy costs, and improve household income. In the same year, De Haro and Koslowski (Reference De Haro and Koslowski2013) carried out a community-based study of fuel poverty in high rise apartments in Edinburgh, Scotland, finding that these buildings were of very poor quality and hard to heat, compounded by exposure to severe weather conditions, resulting in significant health impacts. Later, Snell et al. (Reference Snell, Bevan and Thomson2015) presented the first in-depth study of fuel poverty among disabled people in England, highlighting the highly varied needs and eligibility for fuel poverty and welfare support within this group, despite disabled people typically being treated as a homogeneous grouping. Subsequently, Middlemiss (Reference Middlemiss2017) provided a critical take on the UK government’s transformation of the politics surrounding fuel poverty policy 2010-2015, including the change from an absolute definition of fuel poverty to a relative measure, signalling a shift in considering fuel poverty as a policy issue that should and could be eradicated, to a condition that can at best be alleviated. In Snell et al. (Reference Snell, Lambie-Mumford and Thomson2018), the concept of ‘heat or eat’ was explored, contributing knowledge around the importance of energy billing periods, household composition, and social networks in shaping household experience.

Until Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Hodgson and Bailey2019), there had been minimal focus on ethnicity and fuel poverty within the discipline, which Forster and colleagues contributed to addressing with an evaluation of energy advice for Traveller Communities. Important contributions are also made by Chipango (Reference Chipango2020), who provided the first non-British study, examining the pervasive social scarcity of electricity in Zimbabwe via the lens of social justice. The final study to engage meaningfully with energy poverty came from Bertho et al. (Reference Bertho, Sahakian and Naef2021), who continued the internationalisation of the topic, with a study of energy efficiency and ‘eco-social interventions’ in Switzerland, in which they reveal the invisibility of fuel poverty as a policy concern. A commonality across all papers is a concern for distributional impacts, eligibility for government support, and revealing social injustices. However, except for a handful of papers, the intersection of energy poverty with climate change does not feature heavily.

Integrative review of energy poverty and climate change: tensions and cohesion building

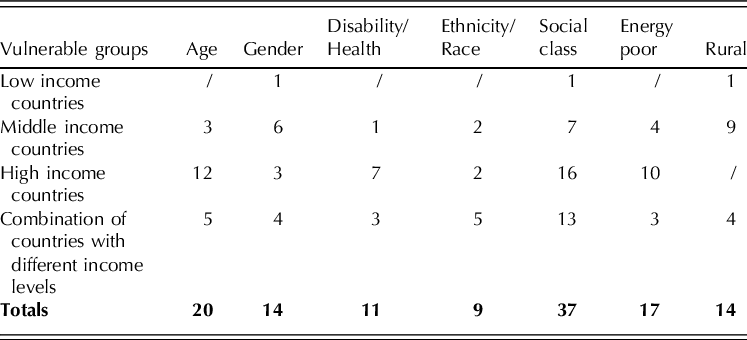

The prevalence of social pillars and vulnerable groups mentioned in the reviewed articles is summarised in Table 2 and Table 3 by country category. We used World Bank country classification by income level of low, middle, and high income countries, calculated based on gross national income per capita (Hamadeh et al., Reference Hamadeh, Van Rompaey, Metreau and Eapen2022). We listed as many social pillars and vulnerable groups as identified in each article, even if one article mentioned multiple categories. We can observe that housing and health are the most referenced social pillars, which are of significant concern to high income countries but not mentioned by articles concerning low income countries. Middle income country studies most frequently mention rural households as a spatially disadvantaged group, whereas high income countries do not mention them. Studies on high income countries deem social class, energy poverty, and age as the most relevant vulnerability categories, which is consistent with what these countries consider as relevant social pillars (housing and health) at the energy poverty and climate change nexus.

Table 2. Mention of key social pillars in the analysed manuscripts shown by income level of referenced countries

Table 3. Mention of vulnerable groups in the analysed manuscripts shown by income level of referenced countries

The consequences of climate change on energy poverty are discussed in various countries, particularly in low and middle income countries (LMICs), as well as in some high income countries with warmer climates. One of the key issues identified is higher temperatures during summer, which increase the demand for cooling (Castaño-Rosa et al., Reference Castaño-Rosa, Barrella, Sánchez-Guevara, Barbosa, Kyprianou, Paschalidou, Thomaidis, Dokupilova, Gouveia, Kádár, Hamed and Palma2021; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Simcock, Bouzarovski and Petrova2019) and further exacerbate climate change. Summer energy poverty poses a clear threat to both electricity grid capacity and human health. Climate vulnerability affects vulnerable groups the most (Falchetta and Mistry, Reference Falchetta and Mistry2021; Okoko et al., Reference Okoko, Reinhard, von Dach, Zah, Kiteme, Owuor and Ehrensperger2017). Moreover, users of traditional energy, such as fuelwood, are often stigmatised for using solid fuels exacerbating climate change (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Islas-Samperio, Grande-Acosta and Manzini2022). However, Munro et al. (Reference Munro, van der Horst and Healy2017) contend that the climate change impacts of fuelwood consumption have been exaggerated; and, in the case of Sierra Leone, they have enabled the uncritical rollout of imported liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) across the country, leaving rural communities with reduced sources of income.

We have observed that energy poor and social class are among the most common vulnerability categories mentioned. This emphasises the close relationship between energy poverty and income, with climate change expected to significantly reduce households’ ability to deal with increased energy prices. Energy prices can increase as a result of policies aimed at mitigating climate change, such as carbon taxes, or as a result of integrating renewable energy into the energy mix (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Baker, Shaw, Kondash, Leiva, Castellanos, Wade, Lord, Van Houtven and Redmon2021; Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero, Reference Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero2012). In some LMICs, dealing with the climate emergency is seen as an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. This is meant by both mitigating climate change and improving energy access through renewable energy projects which will provide low-carbon electrification (Nadimi and Tokimatsu, Reference Nadimi and Tokimatsu2018). This is especially relevant for rural populations lacking adequate access to modern energy services (Gebreslassie and Khellaf, Reference Gebreslassie and Khellaf2021; Setyowati, Reference Setyowati2020). To ensure inclusive participation, the agency of women is discussed. For example, some LMICs encourage the entrepreneurship of women to enable them to access the tools and skills necessary to participate in the energy transition (Antwi, Reference Antwi2022; Bhallamudi and Lingam, Reference Bhallamudi and Lingam2019).

A group of papers mention the need for cohesion between efforts to address climate change and energy poverty. This is because measures aimed at reducing energy poverty might increase energy use and carbon footprints (Chakravarty and Tavoni, Reference Chakravarty and Tavoni2013; Okushima, Reference Okushima2021). On the other hand, without a cohesive approach, energy poor households will likely be left out of opportunities to use renewables and energy efficient appliances (Powells, Reference Powells2009; Suppa et al., Reference Suppa, Steiner and Streckeisen2019). Furthermore, some scholars advocate for ‘sharing energy burdens and benefits’ when deciding policy proposals (Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Heffron, McCauley and Goldthau2016) which aligns with energy justice scholarship claims (Sovacool and Dworkin, Reference Sovacool and Dworkin2015). Nevertheless, when energy access and climate concerns clash regarding whether to build a coal power plant or not, research suggests that enabling energy access is a human right, but the source of energy matters as well (Bedi, Reference Bedi2018). An important aspect is to assess energy needs based on future climate predictions, especially for locations with harsher climates (Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez, Neila González and Hernández2018).

Most papers discuss the use of various technical measures to bridge the gap between reducing energy poverty and mitigating the impacts of climate change. In the LMIC context especially, renewable energy electrification has been identified as a clear solution (Bhide and Monroy, Reference Bhide and Monroy2011). Many of the studied countries in this context, especially in rural areas, lack electricity access. Addressing the fundamental issue of energy poverty through climate-friendly energy access is suggested for these countries. By comparison, in high income economies, the proposed measures focus on improving the energy efficiency of housing. However, this policy can harm those in energy poverty where there are increases in rental prices resulting from energy efficiency improvements. The energy vulnerable cannot afford this increased rent and have to move, a phenomenon referred to as ‘renoviction’ (Grossmann, Reference Grossmann2019). Additionally, vulnerable groups may not have the means to undertake energy efficiency interventions. Some common solutions discussed include solar water heating and low-cost cooling appliances, especially relevant in the context of material deprivation and increasing summer temperatures (Nicholls and Strengers, Reference Nicholls and Strengers2018; Worthmann et al., Reference Worthmann, Dintchev and Worthmann2017).

A diverse set of social measures has been proposed to tackle the impacts of climate policies on the energy poor in the short and mid-term periods. The most common include social tariffs, energy subsidies, and direct financial support (Mayne et al., Reference Mayne, Fawcett and Hyams2017; Okushima, Reference Okushima2021). In some cases, there is an emphasis on overall consumer protection and even a disconnection ban (Nagaj, Reference Nagaj2022). There is debate in a few cases about combining various social and technical measures, but there are also concerns that techno-economic measures may conflict with welfare policies (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Hawkey, McCrone and Tingey2016).

A dozen papers discuss the need to rethink the current governance system, including the participation of a wide range of actors, such as vulnerable groups (Hitchings and Day, Reference Hitchings and Day2011; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Kagawa and Nichols2008). For example, Bangladeshi activists have demanded the protection of energy rights and climate policies in a project with India that increases domestic emissions (Bedi, Reference Bedi2018). To alleviate energy poverty and mitigate climate change, community groups, energy initiatives, and collaboration, in general, should be prioritised. Many arguments in this direction stress the importance of understanding the needs of vulnerable groups, such as low-income households dependent on fuelwood. An interim solution could be evaluating fuelwood quality and introducing efficient stoves (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Islas-Samperio, Grande-Acosta and Manzini2022). The ‘human’ factor needs to be considered in housing or energy efficiency policies (Santangelo and Tondelli, Reference Santangelo and Tondelli2017). For example, a priority is to refurbish the dwellings where the elderly live as they are the most at risk of increasing summer temperatures. When conducting energy efficiency assessments, occupant energy usage behaviour should be considered. Moreover, cross-governmental bodies can account for the cross-sectoral impacts of the tension between climate and social policies (Macmillan et al., Reference Macmillan, Davies, Shrubsole, Luxford, May, Chiu, Trutnevyte, Bobrova and Chalabi2016).

Discussion

There are several key tensions observed between energy poverty and climate change. First, it is the question of uplifting the energy poor from their state of material deprivation to being able to access modern and clean energy fuels but in a way that is not increasing emissions or local pollution. Second, due to climate change and subsequent increasing temperatures and cooling needs, the challenge is to satisfy these needs in a way that does not pose a financial burden to energy poor households or put them at health risk due to avoiding expenditure on cooling.

Indirect tensions can be observed through the increase of energy prices due to the integration of renewables or carbon taxes, which impacts especially the already vulnerable. On the other hand, restrictive environmental policies might affect the livelihood of vulnerable populations due to their dependence on cheap energy sources, such as fuelwood. Measures to address energy demand in the household sector can also shrink the access of the vulnerable to good quality housing, especially relevant in times of increasing temperatures and unpredictable weather events. Extreme cold weather caused by climate change can also increase the need to heat more.

We have established that policy approaches at the nexus of mitigating energy poverty and climate change in high income countries highlight the need to invest in high-quality dwellings and use climate-friendly cooling appliances. These policy suggestions, such as retrofitting and providing energy-efficient appliances, highlight the leading role health and housing sectors can play in mitigating climate change and energy poverty. On the other hand, in LMICs in which vulnerable populations are missing adequate (or at all) access to essential energy services, the suggestions go in line with using renewable energy potential to bring access to clean energy while mitigating carbon emissions (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Silva and Freitas2019; Tàbara et al., Reference Tàbara, Takama, Mishra, Hermanus, Andrew, Diaz, Ziervogel and Lemkow2020; Teixeira Lemba et al., Reference Teixeira Lemba, Ferreira Dias and Robaina2019). In this context, multiple social pillars are relevant, especially social security, housing, health, and employment.

Within the key social pillars, the health sector will be crucial to anticipating and adapting to the impacts of climate change. This is especially relevant in LMICs and high income countries with harsher climates. Because health is a prominent social pillar for old age, the elderly especially in high income countries receive attention (Shortt and Rugkåsa, Reference Shortt and Rugkåsa2007; Wright, Reference Wright2004). The link between health, housing, and old age can be further explored by social policy to prevent climate-induced health impacts on the elderly and improve comfort and wellbeing through housing refurbishment. Overall, social security will be relevant to absorb the externalities of climate change, such as reduced food and fuel availability. This opens the discussion to considering energy as one of the ingredients of Universal Basic Services, such as water, housing, and mobility (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021). Many categories of vulnerability are insufficiently studied at the intersection of climate change and energy poverty, such as ethnicity, gender, age, and others, which should be urgently addressed if we are to achieve climate justice.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

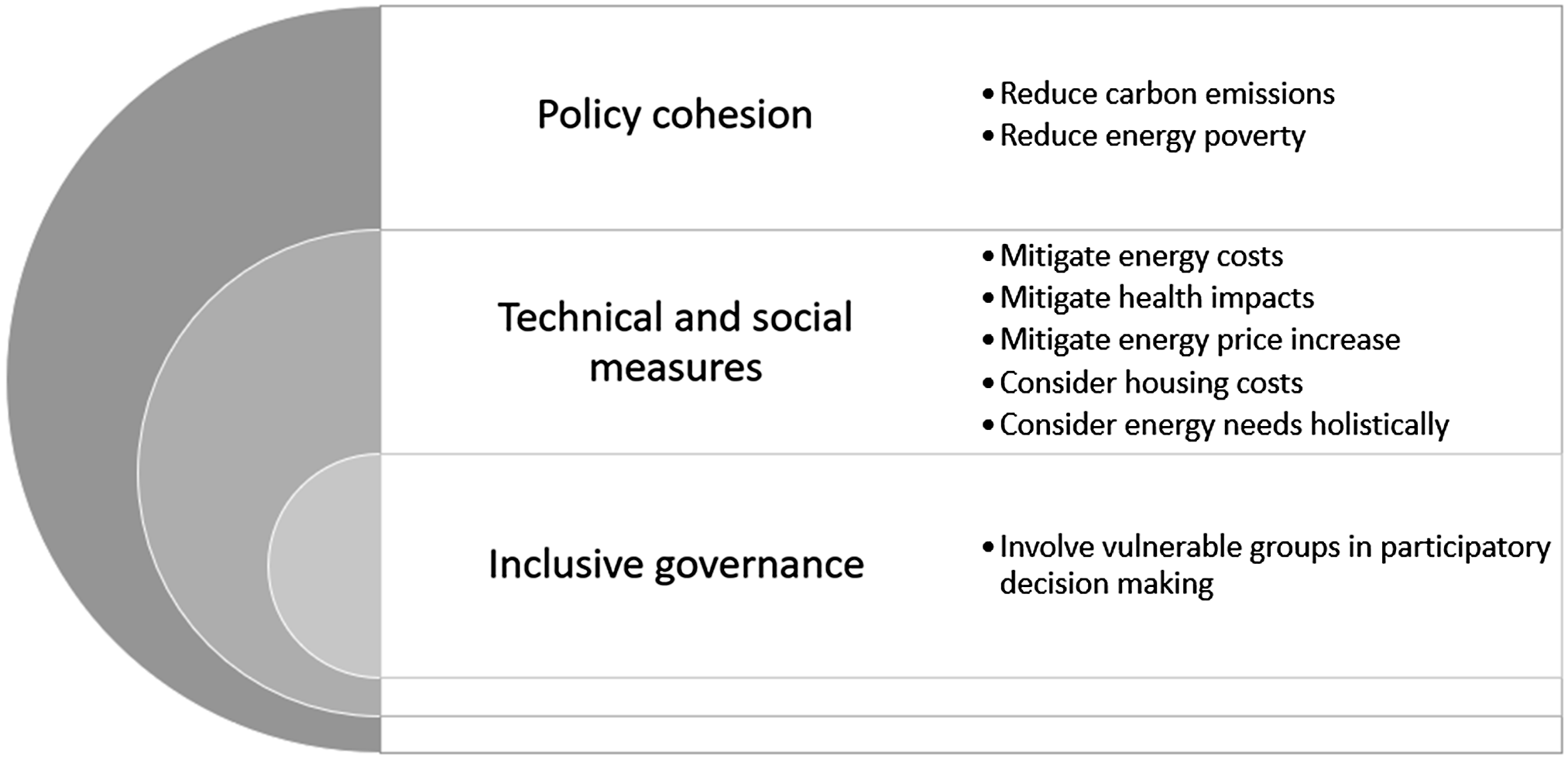

We reviewed literature at the intersection of climate change and energy poverty, identifying critical implications for social policy, and synthesising findings to develop a new conceptual model, drawing out the significance for social policy scholars.

In Figure 3 we illustrate our conceptual framework suggesting a cohesive approach to tackling energy poverty and climate change, relevant to both LMICs and high income countries. There has to be policy cohesion incorporating various policies, especially energy, social, health, and environmental to ensure climate-friendly mitigation of energy poverty. The approach would involve a combination of technical and social measures which consider the threats of climate change on vulnerable groups while being aware of their needs. Finally, an inclusive governance mechanism that actively involves the contribution of those with lived experience of energy poverty is needed.

Figure 3. Creating a cohesive approach to tackle climate change and energy poverty

Energy poverty is a complex multidimensional issue that sits across many government departments and disciplines, which may go some way towards explaining the limited attention to this issue within the discipline of social policy to date. However, as we have seen in section about the scoping review of energy poverty research within the discipline of social policy, there are significant and distinctive contributions to be made by social policy to the issue of energy poverty, and related discussions around clean energy transitions. The need to stay cool in summer emphasises the importance of good building quality, holistic heatwave plans, and the availability of accessible cooling centres. Social welfare support and social housing policies should be directed towards mitigating the increased cooling needs and costs of vulnerable groups. Furthermore, vulnerable populations already experiencing energy poverty will be severely affected by climate change consequences, including a wide range of adverse health and economic impacts prompting the need for adequate labour market, social protection, and health strategies. However, in an attempt to cope with rising energy prices, the use of solid fuels by vulnerable groups adds to carbon emissions deteriorating the climate change situation. Therefore, phasing out environmentally unfriendly fuels should be done only in line with a strong social policy that prevents further material deprivation of those already vulnerable.

Synergies and tensions exist between energy poverty and energy, climate, and social policies. The dominance of techno-economic approaches to understanding energy poverty silences or ignores social differences and differing needs, thus creating an opportunity for social policy to become a driving force in fairly tackling climate change. Thus, technical measures can be evaluated to create cohesion with social policy, while additional research needs to explore technical and social measures designed in cohesion to tackle both climate change and energy poverty. Future research should explore how climate change adds to the needs of vulnerable groups, how energy poverty is a matter of social and climate justice, and how climate policies can align with social policies.

Acknowledgements

The support of the Social Policy Association’s Climate Justice and Social Policy Group in organising the broader participatory workshop series is gratefully acknowledged. We would especially like to thank participants of the ‘Fuel poverty’ workshop theme for their time and ideas, with specific thanks to Karla Ricalde for critically shaping much of the early discussions, Courtney Stephenson for her support with initial scoping reviews of literature, and Lucie Middlemiss in leading breakout discussions. Financing from the University of Birmingham’s School of Social Policy Research and Development Fund is also gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank the Centre for Social Sciences for supporting the open-source funding. An earlier version of the article was presented at the conference ‘Social Dynamics in the post -Covid age’ organised by the Centre for Social Sciences in 2022. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.