The spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) globally affects people in various aspects of their life. Not only does the virus impose a physical threat of infection and the associated possibility of a severe course with its long-term consequences; being exposed to such threat constantly, as well as to changes in social life and the economic situation can harm mental well-being. Indeed, several studies have investigated mental health consequences of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in nationally representative probability samples, most of them referring to the first lockdown in spring 2020 (see online Supplementary Table S1). With some exceptions, most of these studies found higher average levels of self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms during the first months of the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic symptom levels (Daly, Sutin, & Robinson, Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2021; Dawel et al., Reference Dawel, Shou, Smithson, Cherbuin, Banfield, Calear and Batterham2020; Ettman et al., Reference Ettman, Abdalla, Cohen, Sampson, Vivier and Galea2020; Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle, & Berger, Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle and Berger2020; Pieh, Budimir, & Probst, Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John and Abel2020; Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee and Barlow2020; Twenge & Joiner, Reference Twenge and Joiner2020; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Formanek, Mlada, Kagstrom, Mohrova, Mohr and Csemy2020). Meta-analytic evidence from not exclusively representative studies suggests that these increases in psychological distress (PD) were relatively small and recovered over time (Prati & Mancini, Reference Prati and Mancini2021; Robinson, Sutin, Daly, & Jones, Reference Robinson, Sutin, Daly and Jones2021).

Previous research on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic has moreover identified several relevant demographic and socio-economic risk and protective factors. Higher PD during the COVID-19 pandemic has been consistently found to be associated with female gender (Daly & Robinson, Reference Daly and Robinson2020; Daly, Sutin, & Robinson, Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2020; Gijzen et al., Reference Gijzen, Shields-Zeeman, Kleinjan, Kroon, van der Roest, Bolier and de Beurs2020; Holingue et al., Reference Holingue, Badillo-Goicoechea, Riehm, Veldhuis, Thrul, Johnson and Kalb2020; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Shevlin, McBride, Murphy, Karatzias, Bentall and Vallières2020; Li & Wang, Reference Li and Wang2020; Niedzwiedz et al., Reference Niedzwiedz, Green, Benzeval, Campbell, Craig, Demou and Katikireddi2020; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle and Berger2020; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John and Abel2020; Zajacova et al., Reference Zajacova, Jehn, Stackhouse, Choi, Denice, Haan and Ramos2020), younger age (Daly & Robinson, Reference Daly and Robinson2020; Daly et al., Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2020, Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2021; Every-Palmer et al., Reference Every-Palmer, Jenkins, Gendall, Hoek, Beaglehole, Bell and Stanley2020; Holingue et al., Reference Holingue, Badillo-Goicoechea, Riehm, Veldhuis, Thrul, Johnson and Kalb2020; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Shevlin, McBride, Murphy, Karatzias, Bentall and Vallières2020; Li & Wang, Reference Li and Wang2020; Niedzwiedz et al., Reference Niedzwiedz, Green, Benzeval, Campbell, Craig, Demou and Katikireddi2020; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle and Berger2020; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John and Abel2020; Zajacova et al., Reference Zajacova, Jehn, Stackhouse, Choi, Denice, Haan and Ramos2020), pre-existing mental conditions (Daly & Robinson, Reference Daly and Robinson2020; Every-Palmer et al., Reference Every-Palmer, Jenkins, Gendall, Hoek, Beaglehole, Bell and Stanley2020; Holman, Thompson, Garfin, & Silver, Reference Holman, Thompson, Garfin and Silver2020), poor physical health status (Every-Palmer et al., Reference Every-Palmer, Jenkins, Gendall, Hoek, Beaglehole, Bell and Stanley2020; Holman et al., Reference Holman, Thompson, Garfin and Silver2020), and living with young children (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John and Abel2020). The results for level of education, income, and employment status are more heterogenous, with studies finding evidence of these being both potential protective as well as risk factors (Daly & Robinson, Reference Daly and Robinson2020; Daly et al., Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2020; Ettman et al., Reference Ettman, Abdalla, Cohen, Sampson, Vivier and Galea2020; Li & Wang, Reference Li and Wang2020; Niedzwiedz et al., Reference Niedzwiedz, Green, Benzeval, Campbell, Craig, Demou and Katikireddi2020; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John and Abel2020).

The impact of psychological factors on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, has received less attention particularly in representative studies. Identifying such – possibly malleable – psychological factors in the general population will be of great value for informing tailored prevention and intervention efforts to reduce mental health problems and improve well-being during crises (Kunzler et al., Reference Kunzler, Röthke, Günthner, Stoffers-Winterling, Tüscher, Coenen and Lieb2021).

Insights from studies using non-random convenience sampling suggest that several psychological factors are protective factors associated with lower PD or resilience (operationalized as lower PD than expected given a certain exposure to stressors) during the COVID-19 pandemic: these studies found lower PD to be predicted by cognitive flexibility (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, Reference Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam2020; McCracken, Badinlou, Buhrman, & Brocki, Reference McCracken, Badinlou, Buhrman and Brocki2020), grit (McCracken et al., Reference McCracken, Badinlou, Buhrman and Brocki2020), meaning in life (Schnell & Krampe, Reference Schnell and Krampe2020), dispositional mindfulness (Conversano et al., Reference Conversano, Di Giuseppe, Miccoli, Ciacchini, Gemignani and Orrù2020), secure and avoidant attachment styles (Moccia et al., Reference Moccia, Janiri, Pepe, Dattoli, Molinaro, De Martin and Di Nicola2020), optimism (Płomecka et al., Reference Płomecka, Gobbi, Neckels, Radziński, Skórko, Lazzeri and Jawaid2020; Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021), emotional stability (i.e. low neuroticism; Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri, & Pedreira, Reference Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri and Pedreira2020; Flesia et al., Reference Flesia, Monaro, Mazza, Fietta, Colicino, Segatto and Roma2020; Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021), self-control (Flesia et al., Reference Flesia, Monaro, Mazza, Fietta, Colicino, Segatto and Roma2020; Schnell & Krampe, Reference Schnell and Krampe2020), perceived stress recovery (Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021), positive appraisal style and positive appraisal specific to the COVID-19 pandemic (Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021), both positive (Flesia et al., Reference Flesia, Monaro, Mazza, Fietta, Colicino, Segatto and Roma2020; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Sun, Zhang, Wang, Fan, Yang and Xiao2020) and behavioral (Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021) coping skills as well as coping skills specific for the COVID-19 pandemic (Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri and Pedreira2020), making meaning in negative experiences (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ji, Yang, Wang, Zhu and Cai2021), general self-efficacy (Bendau et al., Reference Bendau, Plag, Kunas, Wyka, Ströhle and Petzold2020; Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021), internal locus of control (Flesia et al., Reference Flesia, Monaro, Mazza, Fietta, Colicino, Segatto and Roma2020), and self-esteem (Arima et al., Reference Arima, Takamiya, Furuta, Siriratsivawong, Tsuchiya and Izumi2020).

Due to the non-random sampling strategy of most of the studies until now, it is however difficult to assess to what degree these results generalize to the general population or to what degree they might be driven by (self-) selection of the respondents into the sample (Fink, Reference Fink2003). A further problem that prohibits reliable conclusions from previous studies on psychological factors and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic is the systematic lack of pre-pandemic baseline measurements. Although these studies can thus describe PD during the pandemic or make claims on average changes by referring to average pre-pandemic health in other samples, they cannot draw inferences regarding measures of intra-individual change.

In the current study, we addressed both shortcomings in the literature and investigated the relationship between psychological factors (selected based on cross-sectional findings in a large convenience sample; Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021) and changes in depression and anxiety symptoms (PD) during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample that is both representative of the German household population and has pre-pandemic baseline measures of the same individuals. Moreover, the long-running panel study allowed us to compare these associations to those with changes from 2016 to 2019, a ‘normal’ period without a singular and ubiquitous stressor like the pandemic.

In accordance with most studies on depression and anxiety in the pandemic, we assumed that the pandemic influenced PD, expecting an increase in PD in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019 and 2016. We moreover hypothesized neuroticism and catastrophizing to be risk factors, expecting higher scores to be associated with larger increases or smaller decreases in PD. We finally expected the following psychological factors to be associated with smaller increases or larger decreases in PD, as protective factors: positive reappraisal, putting into perspective, acceptance, use of instrumental support, positive appraisal specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, perceived stress recovery, optimism, and locus of control.

Methods

Participants

The present sample is a subset of the German nationally representative panel study ‘Socio-economic Panel’ (SOEP; Goebel et al., Reference Goebel, Grabka, Liebig, Kroh, Richter, Schröder and Schupp2019; Liebig et al., Reference Liebig, Goebel, Kroh, Schröder, Grabka, Schupp and Zimmermann2019). The SOEP annually surveys over 30 000 participants in more than 20 000 households which come from a stratified random sample of the German household population. For the current study, a random subset of 12 000 households (one participant per household) were contacted via telephone interviews between 1 April 2020 (67 366 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 732 confirmed deaths related to COVID-19 in Germany so far) and 4 July 2020 (196 096 confirmed cases and 9010 confirmed deaths) in the context of the SOEP-CoV study (Entringer et al., Reference Entringer, Kröger, Schupp, Kühne, Liebig, Goebel and Zinn2020; Kühne, Kroh, Liebig, & Zinn, Reference Kühne, Kroh, Liebig and Zinn2020). Data collection was split into nine tranches. Overall, n = 6684 individuals participated in the survey in 2020. All n = 6684 participants were recontacted between 18 January 2021 (2 040 659 confirmed cases and 46 633 confirmed deaths) and 15 February 2021 (2 338 987 confirmed cases and 65 076 confirmed deaths). Altogether, n = 6006 individuals participated in this follow-up survey. Participants were also surveyed in previous years and provided information on PD in 2016 (January–September; N = 5127) and 2019 (January–September; N = 6399); missing values for pre-pandemic PD were imputed. Information on exact timing and size of the individual tranches in 2020 and follow-up assessment in 2021 can be found in online Supplementary Table S2.

Measures

PD was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4), a four-item questionnaire screening for depressive and anxiety symptoms that has already been used in pre-pandemic waves in this sample (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Löwe, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe2009; Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Wahl, Rose, Spitzer, Glaesmer, Wingenfeld and Brähler2010). The PHQ-4 is a validated mental health screening instrument and measures general anxiety and depressive symptoms using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’). Overall, sum scores range from 0 to 12 with classifications into no (0–2), mild (3–5), moderate (6–8), and severe (9–12) symptoms of general anxiety and depression. The PHQ-4 was assessed in 2016, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

The coping dimensions of positive reappraisal, putting into perspective and acceptance were assessed using three single items from the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; Garnefski & Kraaij, Reference Garnefski and Kraaij2007; Loch, Hiller, & Witthöft, Reference Loch, Hiller and Witthöft2011), adapted in wording to assess emotion regulation during the previous 2 weeks. Similarly, catastrophizing was measured using a reformulated item from the CERQ scale ‘catastrophizing’. The rationale for reformulating the CERQ items to reflect state- rather than trait-like coping was to capture emotion regulation strategies specifically used during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, instrumental support-seeking was measured using the first item of the ‘using instrumental support’ scale of the brief COPE (Carver, Reference Carver1997). These coping items were selected because they were identified to load most strongly on three factors that were identified using principal component analysis in yet unpublished research (for details, see online Supplement S2). The items for positive reappraisal, putting into perspective and acceptance loaded most strongly on a factor representing positive appraisal style, using instrumental support best reflected a behavioral coping style factor, whereas catastrophizing best represented maladaptive coping.

Additionally, positive appraisal specific to the COVID-19 pandemic was assessed with two self-formulated items. Perceived stress recovery was measured using one item from the Brief Resilience Scale (Chmitorz et al., Reference Chmitorz, Wenzel, Stieglitz, Kunzler, Bagusat, Helmreich and Tüscher2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dalen, Wiggins, Tooley, Christopher and Bernard2008). All coping, COVID-19 appraisal, and recovery items were answered on a Likert scale from 0 (‘don't agree at all’) to 4 (‘fully agree’) and were collected during the 2020 survey period. Optimism was assessed in 2019 using one item asking about the attitude toward the future, ranging from 1 (‘pessimistic’) to 4 (‘optimistic’). Locus of control was assessed in 2015 and measured using a 10-item instrument with a Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘disagree completely’) to 4 (‘agree completely’). Higher values indicate an internal locus of control. Neuroticism was assessed in 2017 using the Big Five Inventory – short version (BFI-S; Hahn, Gottschling, & Spinath, Reference Hahn, Gottschling and Spinath2012). Answers on the 7-point Likert scale range from 1 (‘does not apply’) to 7 (‘applies fully’).

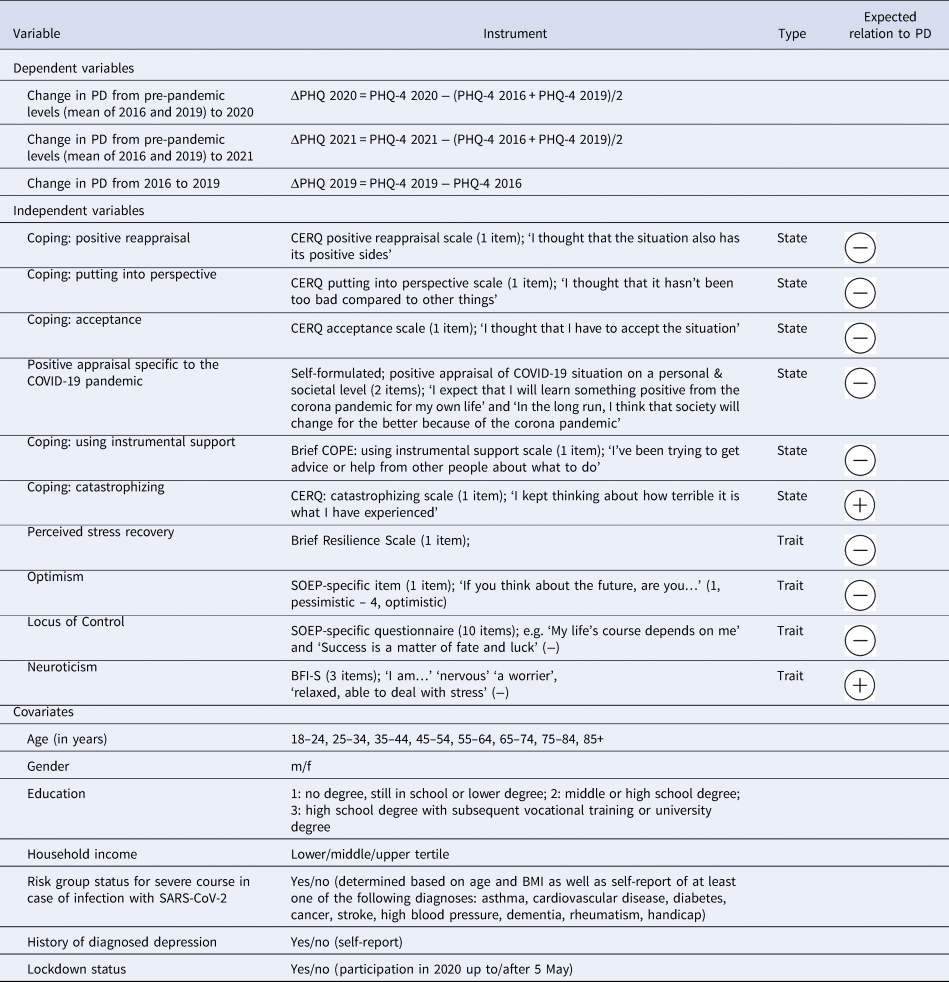

Example items for all measures and information on included covariates can be found in Table 1, which additionally summarizes the hypothesized relation between psychological factors and outcomes. An overview of the timing of data assessment for the different variables can be found in Fig. 1.

Table 1. Overview of variables and instruments used

PD, psychological distress; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; CERQ, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; SOEP, Socio-economic Panel; BFI-S, Big Five Inventory, short version; m, male, f, female; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; BMI, body mass index.

Note. Expected relation to PHQ indicates the hypothesized relationship between the respective independent variable and ΔPHQ 2020 as well as ΔPHQ 2021.

Fig. 1. Timing of data collection for predictors and outcome variables. PHQ-4, Patient Health Questionnaire, 4 item version; ΔPHQ 2019, change in PHQ-4 from 2016 to 2019; ΔPHQ 2020, change in PHQ-4 from 2019 to 2020, ΔPHQ 2021, change in PHQ-4 from 2019 to 2021.

Statistical analyses

Data preprocessing

Data cleaning and analyses were performed in R v4.0.0 (R Core Team, 2020). The code used for preprocessing and analyses is available at https://osf.io/znwjt/.

Missing values (4.5%) were imputed by means of the MICE R package (Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011) using classification and regression trees with m = 5 imputations and 50 iterations. Statistical outliers were all within the range of the used scales, therefore considered meaningful and not removed. Predictor variables were z-standardized; outcome variables were not z-standardized. This enabled (a) comparison between different PD outcomes irrespective of their variance and (b) clinically interpretable evaluation of the relation between psychological factors and absolute change in PD.

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1, pre-pandemic PD was calculated by averaging PHQ-4 scores from 2016 and 2019 to create a more robust baseline. A change in PD was then calculated by taking difference scores between pre-pandemic PD to 2020 (ΔPHQ 2020) and pre-pandemic PD to 2021 (ΔPHQ 2021). To better understand whether the examined psychological factors predicted change specifically during the COVID-19 pandemic or were generally related to changes in PD over time, we additionally investigated the relation of the predictors with the change in PD from 2016 to 2019 (ΔPHQ 2019).

Descriptive statistics

We conducted survey-weighted linear models to compare levels in PD between pre- and peri-pandemic survey waves.

Testing of main hypotheses

The above-mentioned hypotheses were tested using separate multiple linear regression analyses for each psychological factor/outcome pair, including all covariates in each model. This resulted in 10 regressions per outcome. Results were Bonferroni-corrected and hence considered significant at p < 0.005. Baseline PD levels were added to the models as an additional covariate to control for regression to the mean; we however refrain from reporting their associations with changes in PD. To counteract possible biases in sample selection and due to selective response rates, population survey weights were used (Kroh, Reference Kroh2009; Siegers, Steinhauer, & Dührsen, Reference Siegers, Steinhauer and Dührsen2021). Because the survey weight was zero for 27 participants, final sample size was n = 6657 (n = 5981 at follow-up).

In order to determine which of the significant predictors found were most strongly associated with the outcomes in the multivariate setting with partly correlated variables, and at the same time avoid overfitting in a model with many predictors, we subsequently conducted LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator)-regularized regression analyses (Hastie, Tibshirani, & Wainwright, Reference Hastie, Tibshirani and Wainwright2015) using the miselect R package (Rix & Du, Reference Rix and Du2020) and calculated inclusion frequencies. Details on this analysis can be found in online Supplement S3. Note that it was not possible to include survey weights into the LASSO analysis. As background information for interpretation of the unweighted LASSO results, a comparison of results from the unweighted linear regressions and weighted linear regressions can therefore be found in online Supplementary Table S3.

Additional analyses

As robustness analyses, we ran multiverse or specification curve analyses (Simonsohn, Simmons, & Nelson, Reference Simonsohn, Simmons and Nelson2020; Steegen, Tuerlinckx, Gelman, & Vanpaemel, Reference Steegen, Tuerlinckx, Gelman and Vanpaemel2016). Here, slightly different model specifications (linear v. robust regression, cube-root-transformation of non-normally distributed variables v. no transformation) were used to ensure that small arbitrary changes did not have major influences on the results of the study (see online Supplement S4).

To investigate how the psychological factors are associated with PHQ-4 in the individual years (vs. the change between years), we ran linear mixed models and estimated margins (mean ± 1 s.d.) for all predictors (see online Supplement S5).

Results

Sample description

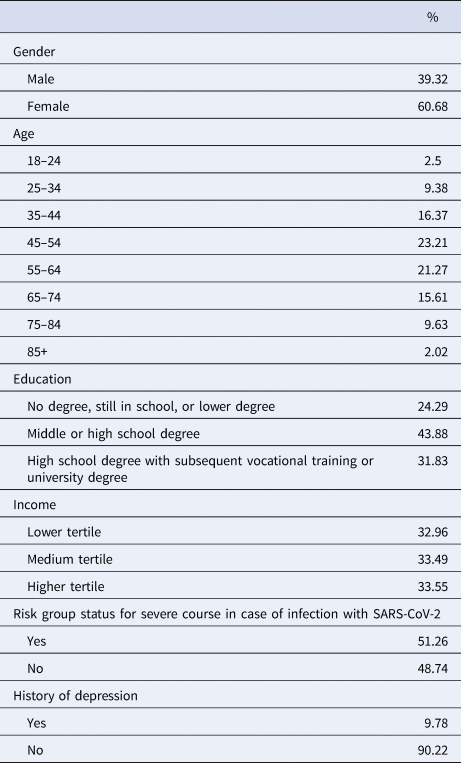

Between April and June 2020, 31% (v. 20% in 2019 and 28% in 2016) of the population reported mild, 5% (v. 4% in 2019 and 6% in 2016) moderate, and 2% (v. 2% in 2019 and 2% in 2016) severe PD. Peri-pandemic PHQ-4 in 2020 (weighted M = 2.45/12, s.e.m. = 0.049) was significantly elevated compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019 [weighted M = 1.79/12, s.e.m. = 0.048; t(6655) = 9.73, p < 2.2 × 10−16] and 2016 [weighted M = 2.17/12, s.e.m. = 0.061; t(6655) = 3.34, p = 0.002]. In January and February 2021, 29% reported mild, 5% moderate, and 2% severe symptoms. Peri-pandemic PHQ-4 in 2021 (M = 2.21/12, s.e.m. = 0.048) was significantly elevated compared to 2019 [t(6655) = 6.07, p = 1.345 × 10−8], but not compared to 2016 [t(6655) = 0.455, p = 0.653], and significantly lower than in 2020 [t(6655) = −3.41, p = 7.31 × 10−4]. Figure 2 displays weighted means and 95% confidence interval of the mean for PHQ-4 across the different years (panel a) and the nine individual tranches assessed in 2020 (panel b) Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Fig. 2. Psychological distress (PHQ-4) across years (a) and across the nine tranches ranging from 1 April to 28 June 2020 (b).

Note. Error bars depict the 95% confidence interval. PHQ-4 values range from 0 to 12, higher values indicating higher PD. As weighted means are used, means of each individual tranche are representative for the German population. In (b), weighted mean PHQ-4 values of the entire sample in 2016 and 2019 are displayed as dotted and dashed horizontal lines, respectively.

Table 2. Sample characteristics (N = 6684)

Socio-demographic variables

With respect to socio-demographic factors, history of depression was positively related to ΔPHQ 2020 (β = 0.697), ΔPHQ 2021 (β = 1.063), and ΔPHQ 2019 (β = 2.060). Age group 18–24 (β = 1.075) and female gender (β = 0.419) were positively related to ΔPHQ 2021. All other socio-demographic variables were not significantly related to the outcomes. Exact relations of all covariates with the outcomes can be found in online Supplementary Tables S4–S6.

Multiple linear regressions

As hypothesized, perceived recovery (β = −0.473) and reappraisal (β = −0.192) were negatively, whereas catastrophizing (β = 0.553) and neuroticism (β = 0.214) were positively related to ΔPHQ 2020. Contrary to our hypotheses, instrumental support-seeking (β = 0.282) was also positively related. All other predictors were not significantly associated with ΔPHQ 2020 (see online Supplementary Table S4).

As expected, perceived recovery (β = −0.332) and optimism (β = −0.139) were negatively, whereas catastrophizing (β = 0.259) and neuroticism (β = 0.355) were positively associated with ΔPHQ 2021. Instrumental support-seeking (β = 0.170) was again positively related. All other predictors were not significantly associated with ΔPHQ 2021 (see online Supplementary Table S5).

To see if these factors were specifically relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic or also relevant before, we repeated the analyses with the change in PD during a control period (2016–2019) as the outcome (see online Supplementary Table S6). Optimism (β = −0.175) was negatively, whereas neuroticism (β = 0.421) was positively associated with ΔPHQ 2019. All other psychological factors were not related. Beta coefficients for all psychological factors and all outcomes are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Beta coefficients of multiple linear regressions for ΔPHQ 2020 (a), ΔPHQ 2021 (b), and ΔPHQ 2019 (c).

Note. This figure shows beta coefficients of the psychological factors for the three outcomes. Complete output tables of the respective linear regressions can be found in online Supplementary Tables S4–S6. Predictors are z-standardized, outcomes are not standardized. Error bars depict the 95% confidence interval.

LASSO-regularized regressions

LASSO-regularized regression analysis highlighted the roles of catastrophizing, perceived recovery, neuroticism, and asking for instrumental support for ΔPHQ 2020, of neuroticism, perceived recovery, and catastrophizing for ΔPHQ 2021, and of neuroticism as well as optimism for ΔPHQ 2019 (see online Supplementary Table S7).

Specification curve analyses

The performed specification curve analyses indicate that results remained stable across model specifications (see online Supplement S4).

Linear mixed models

Linear mixed models revealed similar patterns of predictors for pre- v. peri-pandemic PHQ-4 compared to the multiple linear regressions on ΔPHQ outcomes (see online Supplement S5).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate if mean PD increased compared to pre-pandemic times and which risk and resilience factors are associated with the change in PD in a sample representative of the German household population.

First, as expected, we found that PD was on average significantly higher in both 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019. It however must be mentioned that pre-pandemic PD in 2019 was lower than in 2016. Due to these PD fluctuations at baseline, averaged baseline scores were used in all subsequent analyses.

Second, in line with our hypotheses, we found catastrophizing and neuroticism to be risk factors for PD. Unexpectedly, asking for instrumental support also was positively associated with PD across peri-pandemic outcomes.

Third, the most consistent protective factor across all analyses was self-perceived recovery from stress, whereas other factors like optimism and positive reappraisal where only partially supported as protective factors. Contrary to our expectations, putting things into perspective, acceptance, and positive appraisal specific to the COVID-19 pandemic did not emerge as protective factors. We will discuss these results in more detail below.

PD increase in the general population

In our analyses there was an increase in PD in 2020 (2.45) and 2021 (2.21) compared to 2019 (1.79). PD in 2020, but not 2021, was also higher than in 2016 (2.17). PD in 2021 was again significantly lower than that in 2020.

These average numbers are clearly not in the pathological range, as scores of 6 and higher reflect moderate to severe PD. However, systematic increases of average PD into the pathological range can hardly be expected in a sample consisting of over 6000 participants. Especially, the proportion of participants reporting mild (v. no) symptoms was elevated compared to pre-pandemic times. Our findings of only small but significant increases during the pandemic are in accordance with many other findings in population-based studies (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2020; Niedzwiedz et al., Reference Niedzwiedz, Green, Benzeval, Campbell, Craig, Demou and Katikireddi2020; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle and Berger2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John and Abel2020; Twenge & Joiner, Reference Twenge and Joiner2020). Intriguingly, this small effect may be caused by (vulnerable) subpopulations as indicated by longitudinal samples (e.g. Ahrens et al., Reference Ahrens, Neumann, Kollmann, Plichta, Lieb, Tüscher and Reif2021).

Existing meta-analytic evidence suggests a recovery of PD over time (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Sutin, Daly and Jones2021). In our sample, PD in 2021 was still elevated, which we attribute to the fact that unlike the studies included in the meta-analysis, we covered a later time point in the middle of another wave of COVID-19 infections. PD in 2021 was however lower than that in 2020. This might on the one hand be explained by a habituation effect to the pandemic consequences, including an adjustment to the changes in daily life and social distancing measures. On the other hand, the existence of more precise knowledge about the virus and the prospect of starting vaccination campaigns in Germany in the beginning of 2021 might have led to lower uncertainty compared to 2020 and therefore a different appraisal of the situation, which in turn differentially influenced mental well-being.

Risk factors for PD

Female gender and younger age were socio-demographic risk factors for peri-pandemic PD in 2021 but not in 2020, adding to the mixed picture that although many studies reported these to be risk factors (see Introduction), meta-analytic evidence did not find this relationship (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Sutin, Daly and Jones2021). The most important psychological risk factor was catastrophizing as it showed positive associations with PD changes across peri-pandemic analyses (but not in the control analyses for the pre-pandemic change from 2016 to 2019). Catastrophizing is the tendency to think that things are worse than they are or will have a far worse outcome than is realistic. Confirming previous research that highlights catastrophizing as one of the most prominent emotion regulation strategies predicting PD (Garnefski & Kraaij, Reference Garnefski and Kraaij2007; Martin & Dahlen, Reference Martin and Dahlen2005), our results indicate that this type of coping is the most maladaptive of those included as predictor. Neuroticism also showed a positive association with PD outcomes in almost all analyses, also for the pre-pandemic control analyses, an association that is well known from the literature (Lahey, Reference Lahey2009). Unexpectedly, asking for instrumental support as coping strategy also emerged as quite consistently positively associated with PD, contrary to what we hypothesized. However, it is conceivable that this predictor was confounded with having negative experiences or symptoms in the first place. The specific formulation of this item was: ‘I've been trying to get advice or help from other people about what to do’. People might have only reached out to other people for help if they already experienced significant burden, whereas individuals with less burden might not have sought to do so, especially under the given pandemic circumstances.

Protective factors for PD

Overall, we found perceived recovery from stress to be the most consistent protective factor across peri-pandemic analyses. Optimism and positive reappraisal were at least partially found to be protective factors, consistent with previous research on their association with mental health (Martin & Dahlen, Reference Martin and Dahlen2005; Plomin et al., Reference Plomin, Scheier, Bergeman, Pedersen, Nesselroade and McClearn1992). We did not find support for putting things into perspective, acceptance, and positive appraisal specific to COVID-19 to be protective factors.

Optimism and perceived recovery were the only protective factors associated also with PD change in the pre-pandemic control period.

These findings could thus indicate that the results regarding other psychological protective factors such as positive reappraisal are specific to the COVID-19 pandemic and that they are not related to changes in PD under normal circumstances. However, an additional, and more likely, explanation is that the temporal distance between the assessment of the pre-pandemic PD change score on the one hand and psychological factors assessed in 2020 on the other hand is too large to find associations. The fact that coping items such as positive reappraisal were reformulated to reflect state-like coping in 2020 substantiates this possible explanation, especially since perceived stress recovery, a trait-like measure assessed in the same wave, does show relation to ΔPHQ 2019.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of our study such as the representativeness of the sample and existence of individual pre-pandemic baseline PD, which have been considered important specifically in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Kunzler et al., Reference Kunzler, Röthke, Günthner, Stoffers-Winterling, Tüscher, Coenen and Lieb2021; Nieto, Navas, & Vázquez, Reference Nieto, Navas and Vázquez2020), as well as the comparison with change in PD during a pre-pandemic period and the use of LASSO-regularized regression that selects the most promising variables in a model with many potential variables, there also are several limitations: most importantly, psychological factors were not assessed at all survey waves (see Fig. 1). Given that many psychological factors such as coping may be variable and malleable (Compas, Forsythe, & Wagner, Reference Compas, Forsythe and Wagner1988), this impedes disentangling directionality of causation between psychological factors, PD, and pandemic context. We are also aware of the second major limitation that results from the uneven sampling of psychological factors: we were forced to include variables that were assessed in 2020 to the model predicting change from 2016 to 2019. Our rationale to nevertheless include the factors into the model was to keep the models as similar as possible to set the peri-pandemic results into perspective. We moreover included variables that were assessed during previous survey waves, such as locus of control in 2015, neuroticism in 2017, and optimism in 2019. Although it would have been preferred to have more recent data, based on the literature we expect a relative stability of these constructs (Cobb-Clark & Schurer, Reference Cobb-Clark and Schurer2011, Reference Cobb-Clark and Schurer2013; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, Reference Scheier, Carver and Bridges1994). Other limitations are the self-report nature of assessments and that the use of single items instead of entire validated questionnaires to assess the coping dimensions, although necessary for pragmatic reasons, might have led to a reduced statistical power. Finally, we do not have knowledge of specific stressors that might have occurred between the two measurements; changes in PD from baseline to 2020 and baseline to 2021 can therefore only be partly, and only on average, attributed to experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic. However, although there undoubtedly are other influences on changes in PD that we did not assess and that therefore cannot be controlled for, these are expected to occur at random, whereas every participant experienced the COVID-19 pandemic during data collection.

Outlook

In the present research, we identified several psychological factors that are associated with changes in PD during the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population of Germany. Although due to the used instruments our results can strictly only give insights regarding PD, in light of past findings (Veer et al., Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021) we also expect these psychological factors to be related to general mental health and resilience (i.e. mental health controlled for stressor exposure; see Kalisch et al., Reference Kalisch, Köber, Binder, Ahrens, Basten and Chmitorz2021 for further details). The exact pattern of predictors might certainly be different when investigating these slightly different outcomes. For example, it should be noted that the strongest predictors for PD in our study were those that are conceptually closest to PD (catastrophizing, asking for instrumental support, neuroticism, and perceived stress recovery), whereas psychological factors that are conceptually further away from symptoms such as positive reappraisal, optimism, or locus of control, show weaker relationships with PD. These latter factors however seem to be stronger predictors for resilience, as for instance shown in Veer et al. (Reference Veer, Riepenhausen, Zerban, Wackerhagen, Puhlmann, Engen and Kalisch2021). Future representative studies should investigate this in more detail.

Our results do point to some possibly malleable factors that we found to be prospectively associated with changes in PD during COVID-19 and that are therefore possible candidates for targeted prevention and intervention programs to improve general mental well-being during challenging times such as pandemics. Given the pandemic situation, these prevention efforts should ideally be widely accessible and allow for a remote delivery via internet and/or mobile phone. Above all, improving stress recovery, e.g. via physical exercise in the nature (Wooller, Rogerson, Barton, Micklewright, & Gladwell, Reference Wooller, Rogerson, Barton, Micklewright and Gladwell2018) or smartphone-assisted biofeedback (Hunter, Olah, Williams, Parks, & Pressman, Reference Hunter, Olah, Williams, Parks and Pressman2019), appears to be the most promising starting point. Moreover, reducing catastrophizing tendencies, for example via smartphone-based cognitive behavioral interventions for mental health prevention (Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Van Daele, Nordgreen, Karekla, Compare, Zarbo and Baumeister2018; Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Shanahan, Rohde, Schulz, Wackerhagen, Kobylińska and Kleim2020), increasing internal locus of control, e.g. via online interventions as has been done by Nallapothula et al. (Reference Nallapothula, Lozano, Han, Herrera, Sayson, Levis-Fitzgerald and Maloy2020) in an academic context, increasing optimism, e.g. using the best possible self intervention (Malouff & Schutte, Reference Malouff and Schutte2017), and learning to also see positive aspects in the overall challenging situation, e.g. via mobile cognitive behavioral interventions (Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Van Daele, Nordgreen, Karekla, Compare, Zarbo and Baumeister2018; Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Shanahan, Rohde, Schulz, Wackerhagen, Kobylińska and Kleim2020) are promising paths to increase individual well-being. Future research should corroborate these directions using interventional studies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722000563

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anna Daniels and Sarah A. Wellan for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Financial support

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement numbers 777084 (DynaMORE) and 101016127 (RESPOND). ‘SOEP-CoV: The Spread of the Coronavirus in Germany: Socio-Economic Factors and Consequences’ was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). AR was supported by Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes. HK was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Science Foundation) Grants – 415809395, 427279591, and 40965412. The data can be accessed via the research data center of the SOEP.

Conflict of interest

RK has received advisory honoraria from JoyVentures, Herzlia, Israel.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.