Introduction

Makurian Ghazali, located in the Bayuda Desert of Sudan, was occupied from c. AD 680–1275. The dominant feature of Ghazali is a walled monastery with two churches and communal living facilities (e.g. refectory, dormitory) (Obłuski Reference Obłuski2019: 64–69). Near the monastery are a lay settlement, iron-smelting facilities and four cemeteries (Figure 1). Cemetery 2, south of the monastery, was used by the monastic community, while cemetery 3 abuts the lay settlement and was seemingly used by this community. Use of cemetery 4 remains unclear. Cemetery 1, west of the monastery, was possibly used for ad sanctos burials—burials near locales of religious importance (Ciesielska et al. Reference Ciesielska, Obłuski, Stark, Lohwasser, Karberg and Auenmüller2018; Obłuski Reference Obłuski2018, Reference Obłuski2019; Stark & Ciesielska Reference Stark, Ciesielska, Lohwasser, Karberg and Auenmüller2018).

Figure 1. Location of Ghazali within Sudan (left) and plan of site features (right) (figure by A. Chlebowski, B. Wojciechowski & R. Stark).

Excavations at Ghazali were initially undertaken in the 1950s (Shinnie & Chittick Reference Shinnie and Chittick1961) and subsequently between 2012 and 2017 by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw (PCMA UW), under the Ghazali Archaeological Site Presentation Project (GASP), directed by Artur Obłuski, and in collaboration with the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM) of Sudan and the Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project (QSAP Mission No. 36) (Obłuski Reference Obłuski2018, Reference Obłuski2019). Human remains from Ghazali were excavated, curated and studied with the permission and collaboration of NCAM and descendant communities.

Methods

In 2023, during an examination of the partially naturally mummified remains of Ghz-1-002, an area of darker discolouration was observed on the dorsal surface of the right foot, inconsistent with the appearance of desiccated skin or a textile imprint. A full conversion camera (Canon T7i, 18–55mm lens) was used to capture full-spectrum (ultraviolet to infrared) and visible light images of the foot with a visible bypass filter (75nm range). Image data were decorrelated to distinguish different colours algorithmically in DStretch (Harman Reference Harman2008). Image post-processing in ImageJ/Fiji with a DStretch plugin broadly followed DStretch Tattoo Protocol (Göldner & Deter-Wolf Reference Göldner and Deter-Wolf2023) for images taken in the visible light spectrum (Figure 2A–D). The YXX channel was used in full-spectrum image analysis (Figure 2E–H), as previously tested for multispectral imaging by the first author. DStretch-enhanced images revealed a series of tattoos.

Figure 2. Tattooing on the right foot of Ghz-1-002. Visible light photographs: A) original; B) DStretch (YBK channel) enhanced; C) pigmented pixels enhanced; D) pigmented pixels isolated. Full-spectrum photographs: E) original; F) DStretch (YXX channel) enhanced; G) pigmented pixels enhanced; H) pigmented pixels isolated (photographs by K.A. Guilbault).

Results

Individual Ghz-1-002 was interred in cemetery 1 within a north-west to south-east aligned stone box-grave. The body had been wrapped in a shroud and buried in an extended supine position with the head to the west, right hand along the femur and left hand on the pelvis (Figure 3). Macromorphological pelvic and cranial features (Nikita Reference Nikita2017) identify Ghz-1-002 as a 35–50-year-old probable male. Bone collagen radiocarbon dating returned a date range of cal AD 667–774 (95.4% confidence, Sample ID: OxA-39905).

Figure 3. Burial of individual Ghz-1-002: A) burial dimensions; B) box-grave superstructure; C) the burial in situ (figure by J. Ciesielska).

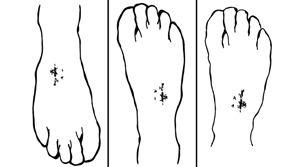

The identified tattoos cover a total area of 16 × 26mm and, in alignment with symbols at Ghazali (Ochała Reference Ochała2023) and elsewhere (Klauser Reference Klauser1954; Jakobielski Reference Jakobielski, Welsby and Daniels1991; Garipzanov Reference Garipzanov2018), comprise three signs: the Greek letters chi (X) and rho (P) superimposed (a ‘Christogram’), accompanied by alpha (A) and omega (Ω or ω) with a bearer-perspective orientation (Figure 4). In Christian symbolism the alpha and omega formulaically flank the Christogram. Stylistically atypical, the layout and appearance of the tattoo may reflect artistic and regional variation, such as examples found elsewhere in medieval Nubia and Christendom (Bisconti Reference Bisconti2000; Garipzanov Reference Garipzanov2018). The appearance of the proposed omega—whether rendered as Ω or the more contextually appropriate ω—requires further consideration as the symbols appear somewhat different in visible (Figure 2D) and full spectrum light (Figure 2H). Underlying hard and soft tissue architecture could have contributed to this variation, in addition to decreasing visible detail in two-dimensional documentation and a loss of definition as pigments diffused during life and subsequent desiccation processes. The detail quality is further dependent on tattooing technology.

Figure 4. Illustrations of tattooing on the right foot of Ghz-1-002 rendered from visible light photographs in standard anatomical (A) and inverted (B) positions and from full-spectrum photographs (C, inverted) (figure by K.A. Guilbault).

Discussion

Tattooing has a long history in the Nile Valley, with tattoos identified on around 45 mummified individuals in ancient Nubia and Egypt, spanning from at least c. 3100 BC–AD 74. These are primarily dots and lines, and all but four are on female bodies (Vila Reference Vila1967; Armelagos Reference Armelagos1969; Tassie Reference Tassie2003; Renaut Reference Renaut and Mouton2020). The tattoo grouping on the foot of Ghz-1-002 marks only the second instance of tattooing from medieval Nubia. The first example, a monogram of Archangel Michael (MIXAHΛ), was identified on the thigh of a 20–35-year-old female at Site 3-J-23 in the Fourth Cataract region (Vandenbeusch & Antoine Reference Vandenbeusch and Antoine2015). Tattooing was also embraced elsewhere in North Africa, notably in Morocco and Ethiopia. Historical research in these regions, although limited, indicates enduring traditions today with parallels seen throughout the Nile Valley (Belhassen Reference Belhassen1976: 61; Johnson Reference Johnson2009).

The tattoos and the interment of Ghz-1-002 in cemetery 1 further suggest this cemetery may have included burials of religiously devout individuals who wished to be interred ad sanctos (Johnson Reference Johnson and Taylor2010; Wiśniewski Reference Wiśniewski2018:83–100), particularly given the development of cemetery 1 in proximity to the monastery at Ghazali despite the existence of an adjacent cemetery (cemetery 3). There is presently no clear evidence that Ghazali was a pilgrimage site, but it is possible, given the well-established case for pilgrimage at nearby Banganarti (Żurawski Reference Żurawski2014; Łajtar Reference Łajtar2020). The location of the tattoo may have been chosen as a private sign of faith, as it was designed to be viewed by the bearer and could be covered easily. A connection with pilgrimage and travel by foot as a devotional act is also possible.

Notwithstanding multifold possible rationales—including alignment with the crucifixion wounds of Christ—tattoo placement appears meaningful and intentional, supporting the tattoos as an embodiment of Christian faith (Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006). It is hoped that additional research will provide further insights.

Acknowledgements

Our colleagues on the Ghazali project, at NCAM and QSAP were pivotal in the completion of field research. The collaboration and insights of Zaki ed-Din Mahmoud, Adam Łajtar, Alexandros Tsakos and Michele R. Buzon are also much appreciated. Gratitude is additionally expressed to our reviewers.

Funding Statement

Ghazali research was funded in part under QSAP Mission No. 36, the University of Warsaw, a National Geographic Society Exploration Grant (NGS-67810R-20), the Max Planck Society and a Purdue University CLA 2022–2023 Global Synergy Research Grant for Students.