Introduction: Ear Training for History

Bend your ear to Saturday, 23 July 1853. On that morning, America's first Black concert vocalist and operatic singer, Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, performed at Stafford House, home of prominent English Abolitionist the Duchess of Sutherland, during her UK tour. Born into captivity on a plantation in Mississippi and raised free in Philadelphia, Taylor Greenfield's voice sounded out the fever pitch of America's conflict over slavery.Footnote 1 A multioctave singer, she smashed boundaries for race and gender as a Black woman who sang “white” vocal repertoire across registers heard as both female and male. Writing on an early public performance in 1851, one newspaper reviewer summed up the revolutionary threat of Taylor Greenfield's voice by stating “we can assure the public that the Union is in no degree periled by it,” meaning of course, that the Union was.Footnote 2 Whether received by pro- or antislavery audiences, Taylor Greenfield's voice was understood to peal out Black emancipation. In his 1855 review of Taylor Greenfield's New York Tabernacle performance, James McCune Smith went as far to compare Taylor Greenfield's voice to the firearms employed by escaped slaves defending their freedom against the Fugitive Slave Act.Footnote 3

A skilled singer of Bel Canto arias, sentimental ballads, and hymns, Taylor Greenfield toured nationally and internationally at a time when few women –and even fewer women of color– appeared on the public stage. Following extensive tours of the American north, western territories, Canada, and the UK between 1851 and 1855, Taylor Greenfield returned to Philadelphia where she maintained a private music studio and supported Black abolitionist and Black feminist enterprises;Footnote 4 in 1855 she sang a benefit in support of Canadian journalist and editor of the Provincial Freeman Mary Ann Shadd's appearance at the Colored National Convention,Footnote 5 and in February of 1865 she performed alongside Frederick Douglass's public lecture on the congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.Footnote 6

Despite these accomplishments, Taylor Greenfield remains largely a footnote in the classical music canon, and virtually absent from theatre and performance studies histories. This, even though her career blazed a trail for Black women variety, musical theatre, and opera performers that followed such as Sissieretta Jones, the Hyers Sisters,Footnote 7 and Marian Anderson. Putting this lineage on the record, Daphne Brooks writes: “Greenfield gave birth to a genealogy of black women's cultural play within classical music forms.”Footnote 8 She argues Taylor Greenfield and Black female artists have consistently engaged with and adulterated the respectable, highbrow sphere of classical music to gain representational traction, resist blackface stereotypes of Black womanhood, and “rescript[ ] their status as ‘non-being.’”Footnote 9 Leaning into the “play” of Brooks genealogy of Black women's performance practice, this essay reframes Taylor Greenfield outside the strict genre classifier of classical music to consider her song within the parameters of the theatrical. Following Black musicologists James Trotter, Arthur La Brew, Eileen Southern, and Rosalyn Story, Brooks places the singer within the genre of classical music, a move made to recuperate Taylor Greenfield from historical discourses that persistently linked the vocalist to popular genres of blackface minstrelsy and sideshow in an attempt to disparage her talent, race, and gender.Footnote 10 Such historiographic moves recuperate Taylor Greenfield from the racist and sexist aspersions that historically attended the alignment of her performance with the theatrical.

Yet to categorize Taylor Greenfield's groundbreaking performance practice as classical music alone disregards the potential for “play” as a site of restoration, utopic possibility, and/or worldmaking. While placing Taylor Greenfield in the classical music canon is important feminist and antiracist historiographic work, this move also inadvertently activates a strand of antitheatricality that obfuscates her agentive aesthetic and political innovations. In this essay I address the lacuna of scholarship on Taylor Greenfield in theatre and performance studies by analyzing her singing as a theatrical event. Developing what I term “ear training for history,” I parse her unique performance practice of juxtaposing perfect corporeal stillness against a voice that seemingly took flight across the sonic terrain of race and gender—what contemporaries referred to as her double-voiced sound. I contend that listening to Taylor Greenfield with an ear trained for history sounds out a Black feminist aesthetics of liberation that otherwise goes unheard.

Taylor Greenfield's performance was described as “double-voiced” in newsprint as early as 1853.Footnote 11 The attributions of double voicedness arose from Taylor Greenfield's hallmark of singing repertoire racialized as “white” as a Black woman, and by her technique of singing alternate verses of select songs in registers naturalized as “female” and “male.” The unprecedented practice of a Black woman crossing both the sonic color line and the gender and sex binary earned Taylor Greenfield renown as the “double-voiced singer” since her vocal transgressions generated perceptual astonishment white audiences could only attribute to more than one body. In 1852, for example, the Daily Capital City Fact wrote that, “although coloured as dark as Ethiopia, she utters notes as pure as if uttered in the words of the Adriatic,” and the Milwaukee Sentinel noted, “But what was our surprise to discover that those low, yet heavy and powerful notes, proceeded from the same person who just before had been singing with the highest, clearest notes of a woman.”Footnote 12 This performance practice was characteristic of Taylor Greenfield's repertoire throughout her career and was frequently billed on programs as the artist singing a “duett” with herself.Footnote 13 For listeners both Black and white, Taylor Greenfield's duets were theatrical insofar as they sonically dramatized conflicting antebellum binaries of race and gender/sex.

Interestingly, the drama of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's vocalizations played out against her remarkable corporeal stillness, the second salient feature of her performance practice. Holding her physical comportment to the strictest standards of Black female respectability, Taylor Greenfield barely moved when performing. As Carla Peterson has noted, Taylor Greenfield's physical stillness refuted and resisted the controlling images of Black womanhood that circulated in the antebellum era, images that linked Black women to hypersexuality and/or masculinity.Footnote 14 At the same time, Taylor Greenfield's physical inscrutability heightened the drama and overall theatrical effect of her double-voicings. Listeners were accustomed to the racial and gender crossings of minstrelsy and sideshow, but such sonic masquerades were also accompanied by visual spectacle that confirmed the racial and gender orders of the day. Taylor Greenfield's visual performance, however, was inert. What body/ies could therefore produce such category defying sounds? The perceived double-body problem of Taylor Greenfield's voice was only ever explicitly acknowledged by the singer in her performance of “I'm Free,” wherein the theatricality of her signature performance repertoire was explicitly translated into a sung drama between two diametrically opposed characters.

The essay that follows performs ear training for history. We learn to listen to Taylor Greenfield against the grain of history by attending to the theatricality of her own double-voicing, and the double-voicing of a constellation of her cultural mimics. In following the proliferating “doubles” surrounding Taylor Greenfield, I take my cue from Joseph Roach's theory of surrogates (or, doubles) in Cities of the Dead. Footnote 15 Understanding sites of cultural doubling as spaces where difference and transgression irrupt and/or are managed, I attune to the cultural field of doubles surrounding Taylor Greenfield to understand how the sonic, defined as any vibratory act, serves as a site to make embodied meaning. First, I address Taylor Greenfield's framing as the racialized double of Jenny Lind, a Swedish concert singer whose American tour overlapped with Taylor Greenfield's, and whose performances created norms for white, female sound. Then I analyze representative sideshow and minstrel performances by white actors (female and male) that mimicked Taylor Greenfield's double-voiced singing as copycat acts. I show how each of these performances worked as double acts by staging sound and visual spectacle as a means of producing an essentialized one to one correspondence between voice and body. Such acts were designed to police and contain the excesses of Taylor Greenfield's perceived racial and gender crossings in service of chattel slavery. For our purposes, these double acts also serve as bellwethers: their archival resonance indicates the stakes of Taylor Greenfield's singing and draws my ears toward her voice as an instrument of Black feminist liberation.

In the penultimate turn of the essay, I return to the theatrical double-voicings of “I'm Free.” Under examination are Taylor Greenfield's received praxis of materializing body “doubles” by singing across sex/gender and the sonic color line, and her pairing of dramatic vocal flight with visual stillness. Whereas the next section of this essay demonstrates how Taylor Greenfield's surrogate doubles worked to structure the meaning of bodies and sound according to the dictates of white supremacy, the final analytic section models listening beyond supremacist frameworks and rehearses how ear training for history patterns alternative epistemes for listening to Black women. Namely, in this final section I track the liberatory potential of Taylor Greenfield's own double-voiced praxis, imagining how it might double back on and over essentialized frameworks for Black women's embodied race, gender, and sound as forged in the Middle Passage and reinforced by copycat double acts. Positioning Taylor Greenfield's voice on its own terms, ear training for history invites us to listen to the singer beyond the historically overdetermined relations of power, material archival conditions, and analytic paradigms that seek to fix how we think we hear or know her voice.

Returning to the 23 July performance at Stafford House, a drawing from the London Illustrated news captures the event (Fig. 1): Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield stands motionless beside a piano, conservatively dressed in black silk with only a touch of white lace embellishment at the neck and a white cap covering her hair. Her posture is stayed, her eyes downcast. In contrast, all other eyes in a packed assemblage of white spectators hungrily take in the singer. A model of poise and respectability, Taylor Greenfield eschewed any lowbrow trappings of the popular stage. The room buzzes with activity: patrons shift in their seats to catch a better view of the performer, anxious aristocrats survey the room, a gentleman pulls out a chair for a wealthy white female attendee, and one open mouthed male patron addresses his female companion in the left foreground of the image. Taylor Greenfield's program for the evening featured the operatic Handel composition “I Know That My Redeemer Livith,” the sentimental “Home Sweet Home,” and Vincent Wallace's traditional “Cradle Song.” No trace of comic minstrel repertoire was programmed.Footnote 16 But on that evening an explicitly theatrical turn of events ensued. Taylor Greenfield performed a new piece written expressly for her by Charles W. Glover: “I'm Free.”Footnote 17 A review from the Musical World contextualizes her performance at length:

This is a song in E minor—or rather, a song-duet—or rather, a dramatic sketch, to use the author's nomenclature. . . . A slave-owner—sung an octave lower by Miss Greenfield—would arrest a she-slave, about to cross the line, and thereupon appeals to his dogs . . . to catch the ship and bring back the she-slave. [The slave-owner] ejaculates to his dogs—. . .

Dogs, hold her fast!

Quick! hold till I come there!

Stop—stop—she's past!

And so it happens; for by the time Mr. Glover has . . . crossed the line of the tonic, and boldly settled himself down on the half close of the dominant, the slave is “past” and “free as air,” setting the dogs and their master, now no longer hers, at defiance. By a graceful transition, Mr. Glover now passes into the relative major, and the she-slave—sung by Miss Greenfield an octave higher—thanks God for her deliverance. Mr. Glover, however, still unsatisfied, returns to E minor, and the slave-owner—sung by Miss Greenfield an octave lower—burst out into the following eloquent objurgation:—

Death! there she stands!

That breast, that coal-black hair,

Those hands and feet!

Then comes a phrase in G minor . . . about “who burnt the brand,” in which, with an alternation of octaves, slave-owner and slave befoul each other with foul words; the latter admonishing the former, “that God has branded him on both sides;” the whole ending with a refrain in which the she-slave—sung an octave higher by Miss Greenfield—exults in the possession of freedom, in G major.Footnote 18

Figure 1. Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield performs a “Grand Concert at Stafford House.” Image from the Illustrated London News, 23.635 (Saturday, 30 July 1853), 64. Copyright © Illustrated London News/Mary Evans Picture Library.

Though the sheet music for “I'm Free” has been lost, reviews such as this one clarify the song staged a scene of fugitivity wherein an enslaved woman escapes to freedom across the Mason–Dixon Line, pursued by her enslaver. Given the similarity of this dramatic scenario to the global sensation scene of Eliza's flight across the Ohio River in the stage adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin, it is reasonable to deduce the enslaved character of “I'm Free” was likewise fleeing across that same body of water, this time on the very ferry that had been out of service for Eliza's fictional flight.Footnote 19 Identified by Musical World as a dramatic “song-duet,” “I'm Free” deployed Taylor Greenfield's signature double-voiced performance practice, this time assigning the explicit personages of a white male enslaver and a fugitive Black bondswoman to the multiple bodies listeners thought they perceived when listening to the singer.

Both hallmarks of Taylor Greenfield's repertoire were on display in “I'm Free.” She evoked the persona of a male enslaver through a verse sung in a masculine-coded register (identified by the Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser of London as “the lowest tones of bass music”), while a soprano vocal line sung up the octave represented the persona of an enslaved Black woman.Footnote 20 As for how Taylor Greenfield performatively evoked sonic “whiteness” or “blackness” to denote the characters, she did not. To begin, the performance was overtly racialized, as the characterizations of “master” and “slave” make explicit a binary racialized logic. Additionally, both Glover brothers composed parlor music: sentimental ballads, traditional airs, and adaptations of popular and operatic melodies. This parlor style, adjacent to highbrow “classical music,” was designed for singing in the respectable middle-class home and was racialized as “white.”Footnote 21 Thus the perceived sonic “whiteness” of the song adhered in its musical genre, while the simple existence of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's Black, female body would have sufficed for auditors to materialize the persona of the female bondswoman. As Chybowski argues, essentialized and racist modes of hearing meant audience members would have perceived no impersonation at all, but would have interpreted this character enactment as evidence of Taylor Greenfield's authentic identity as a singing (former) enslaved person.Footnote 22

Although the nature of the freedom narrativized by “I'm Free” was highly controlled by the discourses and power dynamics of white women's abolitionism, the unfettering to which I attend in this essay is not located within the song's discourse, but within its performance practice.Footnote 23 I contend Taylor Greenfield turned Glover's romantically racialized narrative of freedom into a Black feminist scene of emancipation by activating two long-standing and unique features of her performance practice: singing duets with herself across the terrain of explicitly gendered and racialized sound, and doing so in complete stillness.

Using the dramatic sketch of “I'm Free” as a lens for understanding the radical interventions of Taylor Greenfield's double-voiced performance practice, I contend the performative efficacy of her technique lay in its troubling essentialized presumptions of a one-to-one correspondence between body and voice. Ultimately, voices—like bodies—are materialized by and materialize performative enactments. In “I'm Free,” Taylor Greenfield's double-voicing doubled back on white supremacist prescriptions, forged in the Middle Passage, of Black women's embodiment.Footnote 24 By creating new possibilities and meanings for Black women's embodiment through her performance practice of double-voicing, Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's singing redefined liberation according to a Black feminist politics of the flesh. Her double-voicing not only engendered new corporeal and aesthetic spaces of refuge for Black women to inhabit, but also undermined white abolitionists' mechanism of control, and a chattel slavery system reliant on the disciplining and reproduction of Black women's embodied labor.

Sound studies scholars Nina Eidsheim, Jennifer Stoever, and Matthew D. Morrison have detailed how the racism of the nineteenth century structured auditors’ listening, and I build on their work to intervene in how racism tracks the archival record. Nina Eidsheim details how Taylor Greenfield's listeners’ visual racial biases lead to the fantasized perception of “sonic blackness” when none existed. Cued by a visually perceptible Black body, white listeners perceive phantasmic sonic “blackness” in a voice that otherwise met the standards of sonically “white,” classical music.Footnote 25 Eidsheim's theory builds from Mendi Obadike's concept of “acousmatic blackness,” which describes how sound conjures stereotypical Black bodies when those bodies themselves are not present.Footnote 26 Jennifer Stoever reads Taylor Greenfield's singing to detail the gendered formation of the sonic color line—the aural edge of white supremacy. In her eponymous monograph, Stoever charts a nineteenth- and twentieth-century genealogy of how sound was essentialized as white or Black, and highlights Greenfield's and Lind's tours as the events that catalyzed the public policing of vocal “whiteness” and “blackness.”Footnote 27 In his groundbreaking study “Race, Blacksound, and the (Re)Making of Musicological Discourse,” Matthew Morrison outlines how the sonic aesthetics of blackface minstrelsy persists in and out of the burnt-cork mask and work to “delimit black performativity, black personhood, and the ability for black people to be” in its structuration of popular entertainment, the music industry, intellectual property, academic epistemes, and American culture writ large.Footnote 28

I work from these scholars to highlight how contemporary performance historiography struggles against historically biased sonic epistemes. Roshanak Kheshti argues that historical recordings, be they wax cylinders or, in this instance, historic newspaper reviews, work to structure the hearing and subject positions of future listeners.Footnote 29 Thus, it becomes both a historiographic and epistemological challenge to attend to Taylor Greenfield's vocal production through the echo chamber of the nineteenth-century archive, which aspires to filter my hearing and thought through patriarchal white supremacy. Eidsheim, Stoever, and Morrison approach this historiographic challenge with critical race analysis of the problem itself, detailing the racial formation of nineteenth-century critical reception. Yet there remains a dearth of work on Taylor Greenfield's vocal production. What scholarship does exist recuperates Taylor Greenfield in the classical music cannon as a discursive rebuttal of the historic racism and misogyny that sought to denigrate her accomplishments by aligning her with minstrel and sideshow stages. These moves, though critical to antiracist work within historical musicology, also indirectly promote an antitheatricality that forecloses agentive countermemory of Taylor Greenfield's vocal production.

I therefore propose a new historiographic method: ear training for history. Ear training for history attunes to the archive for evidence not of how a voice sounded, but of how it acted. Ear training for history begins with the primary assumption that voice is what McMahon, Herrera, and I have elsewhere termed a “sound act,” an analytic emphasizing sound as the message of a vibrating body, otherwise understood as a body in performance.Footnote 30 This analytic holds that sound is a constellation of acts, and weds the tools of sound and performance studies to analyze how the sonic performs. Here, I want to nuance the formulation of sound act further. Acknowledging its parent fields’ particular strengths in attending to the material and corporeal, a sound act, and by extension ear training for history, attends to the message of a vibrating body as a multisensory experience that is performatively coalesced across visual, sonic, haptic (i.e., vibratory), and kinetic registers.Footnote 31 Rather than an ableist trope, ear training for history is a synecdochical turn of phrase that indexes archival decipherment as a performance-based research methodology, one that relies upon embodied knowledge across multiple activated registers of a sensorium.Footnote 32 Building off the concept of a sound act, ear training for history centers voice as an embodied site of theatrical performance, and holds that as bodies can produce a voice, voice performance can enact a body. In this essay, I locate ear training for history as a method for sounding out “sound acts” in historical contexts where the overdetermination of the archive (history with a capital “H”), disciplinary strictures, and structuration of our contemporaneous sensoria by power foreclose what Ashon Crawley might define as “otherwise” possibilities for listening and receiving.Footnote 33 Against these odds, ear training for history animates Taylor Greenfield's vocal acts as a body of evidence about Black feminist politics and aesthetics.

The Black Swan and Her Doubles

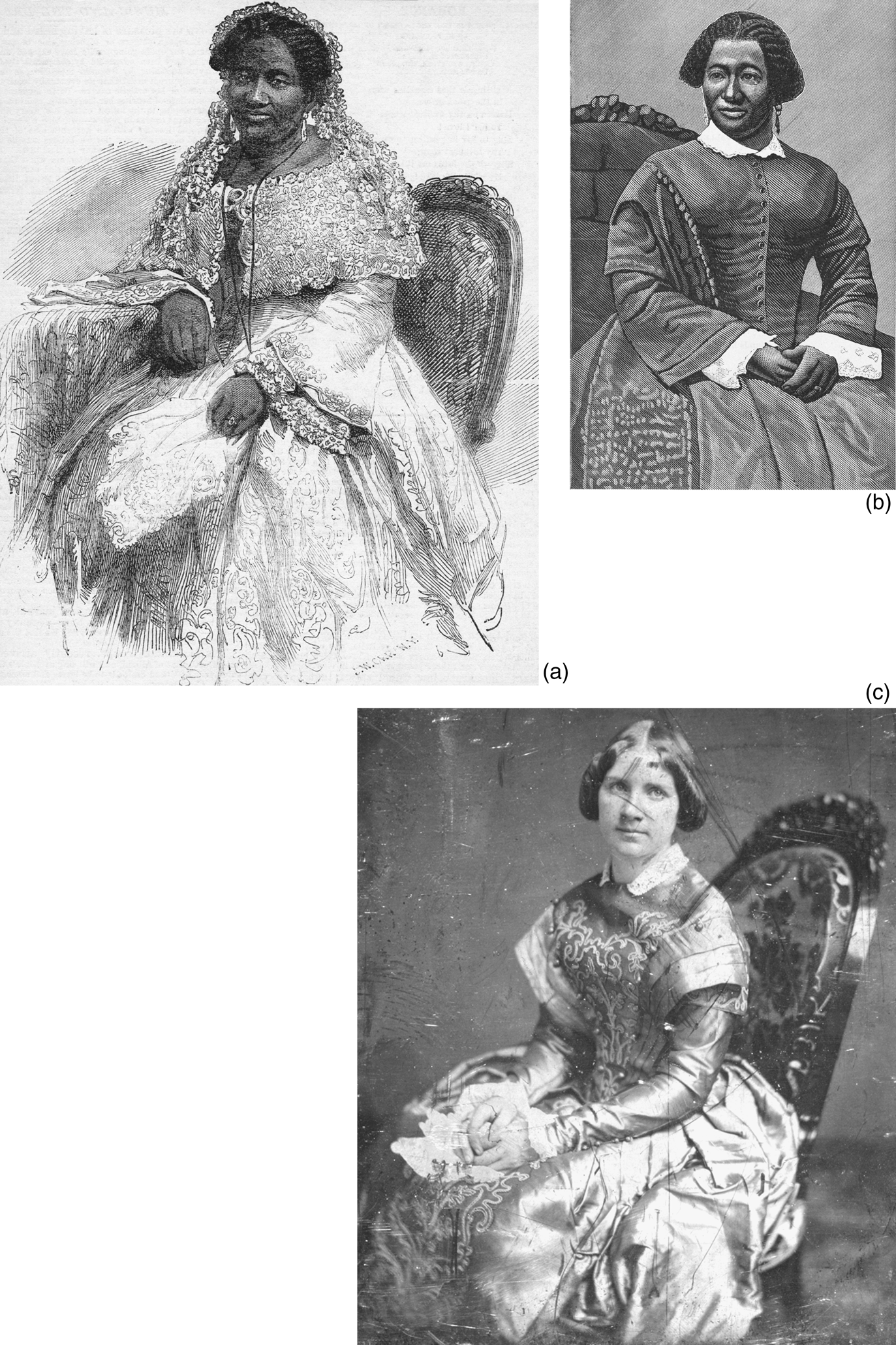

The first step of ear training for history is to denaturalize past sound acts that overdetermine how Taylor Greenfield is heard today. The most prevalent doubling discourse surrounding the Taylor Greenfield archive is her framing as the double of Jenny Lind. Lind was popularly known as “the Swedish Nightingale”; Taylor Greenfield's sobriquet, “The Black Swan,” was meant simultaneously to exoticize and denigrate her within an economy of racial fun that established her as Lind's racialized double—as “Jenny Lind blacked up.”Footnote 34 Contemporary scholars working to recuperate Taylor Greenfield have drawn parallels between her and Lind—noting shared repertoire, public personas, and using each as a measuring stick for the other.Footnote 35 Lind, for example, was the paradigm for virtuous white womanhood in public at a time when women “onstage” were understood as monstrous. Barnum—Lind's tour manager—engineered the singer's race- and gender-defining performance with a series of high-art concerts wherein Lind performed sentimental vocal music with a remarkably restrained embodiment designed to establish white femininity as highly sexualized yet disembodied.Footnote 36 Following Peterson's line of thinking, by patterning herself after Lind, Taylor Greenfield may have worked to cultivate Black respectability and mitigate the racialized sexualization indexed by the projected frames of minstrelsy and sideshow.Footnote 37 And indeed, observe the similarities between Taylor Greenfield and Lind in the promotional images shown as Figure 2. Both women wear lightly ornamented clothing, and share body orientations, postures, gazes, style, and drape of dress, as well as hairstyle. The wood engraving of Taylor Greenfield and photo of Lind show the Swan and Nightingale both with sentimental handkerchief props. Even the chintz patterning on the two women's armchairs matches.

Figure 2. A wood engraving (a) and a still image (b) of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield next to a daguerreotype (c) of Jenny Lind. Images of Taylor Greenfield courtesy of the Wallach Division Picture Collection and Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, both at the New York Public Library. Image of Jenny Lind courtesy of the Library of Congress.

However, I want to trouble the Swedish Nightingale–Black Swan doubling rhetoric. To begin, such frames were deployed by Taylor Greenfield's racist detractors to denigrate and dismiss the singer's artistry by framing her as Lind's comic racial mimic. Additionally, such rhetoric complicates the performance historiography of Taylor Greenfield by ensconcing her within the realm of classical music—the high-art sphere within which both women were originally positioned by managers to mitigate gendered and racialized dispersions accompanying public performance. This is not a challenge to the Black scholarship that, since the late 1960s, has worked to recuperate Taylor Greenfield within the classical music canon; rather, taking a note from Jon Cruz, who highlights Black music as a scene wherein power struggles play out, I point up historic discursive struggle over the disciplinary or genre framing of Taylor Greenfield as ongoing contestation over the rights to a Black woman's body.Footnote 38 This is to say that I understand ongoing debates surrounding Taylor Greenfield's historical placement as an extension of those debates surrounding her early reception. Understanding all historiographic moves as fundamental engagements with the question of power, this essay imagines how Taylor Greenfield may have used her singing to restore her own power in and over her corporeality. For example, existing scholarship indicates Taylor Greenfield's performance practice of singing across gendered registers was a move to showcase her impressive vocal range.Footnote 39 Although accurate, such assessments also normalize the singer's performance practice within the formal bounds of historical musicology, a field that, Morrison shows us, is constituted by the material and epistemological (re)production and exclusion of Blacksound.Footnote 40 Far from the antebellum norm, and in no way comparable to any of Lind's repertoire, Taylor Greenfield's multiregister singing exceeds the current binary that exists between historians wishing to place her within the strict disciplinary bounds of classical music, and her contemporaneous racist and sexist detractors who labeled her transgressive performance practice as minstrelsy or freakery. Ear training for history works across musicology, sound, performance, and Black feminist studies to consider Taylor Greenfield's double-voiced singing as a theatrical act to emphasize her performance practice as a site of aesthetic and political knowledge production.

Taylor Greenfield's double voice was both so radical and so unique it exceeded the logics of surrogation in the “Swedish Nightingale–Black Swan” discourses, and spawned an entirely separate, and heretofore unacknowledged, genealogy of doubles. These doubles, which cannot be traced to Lind but rather only to Taylor Greenfield, proliferated within America's two predominant popular performance genres: sideshow and blackface minstrelsy. In these acts, the surrogate doubles contained Taylor Greenfield's vocal agency by transmuting her sonic transgressions into visual spectacles of racial and gender crossing. Then, by mobilizing the operative performance technologies of sideshow and minstrelsy—enfreakment and racial masquerade—these popular genres reframed Taylor Greenfield's voice not as an instrument of revolution, but as an instrument for the discipline and policing of the Black female body.

Evoking ear training for history, I attend to Taylor Greenfield's surrogate doubles because these sideshow and blackface minstrelsy performances epitomize sound acts in two ways. First, they are explicitly and excessively theatrical, pointing up the dramatic conflict audiences believed they heard in Taylor Greenfield's own singing. Second, the theatricality of these surrogate performances hinges on materializing the racial and gendered transgressions of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's double-voice into discreet, embodied, and visually represented correlates: in short, these doubles materialized multiple theatrical bodies. In explicitly staging vocal sound, these acts worked to control Taylor Greenfield's fugitive embodiments by dragging her perceived vocal transgressions into the realm of the visible where they could be patrolled.

I track how Taylor Greenfield's doubles staged sound to produce and police racialized and gendered power, the very foundations of the hegemonic chattel slave system. Attending to these sound acts is not simply an exercise in rehearsing how patriarchal white supremacy played out. Rather, identifying these doubled performances as sound acts opens a historiographic path to understanding how Taylor Greenfield's singing inaugurated material, embodied performative effects in service of no power but her own.

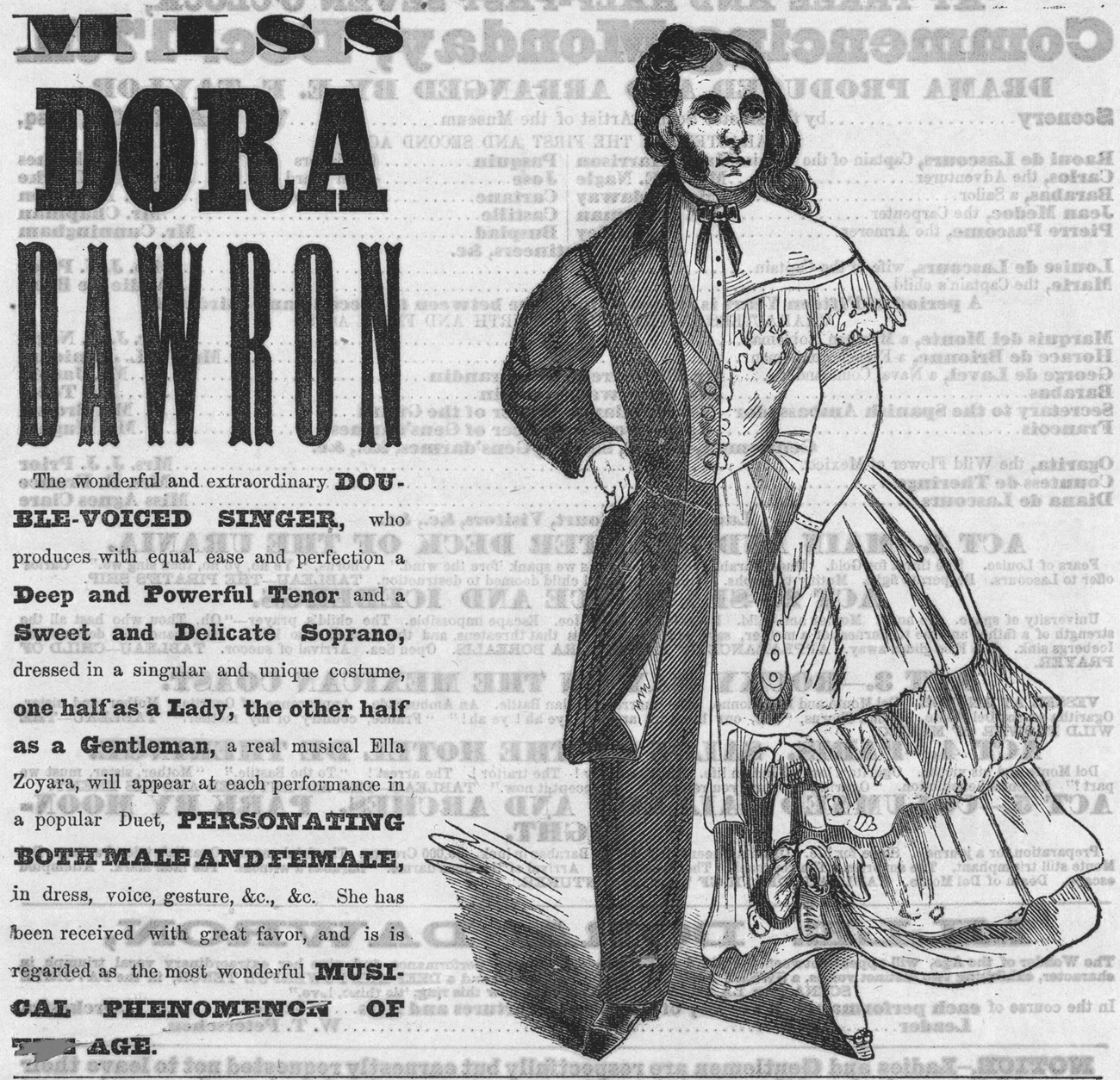

Consider one of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's many doubles: Dora Dawron, the “double-voiced” singer of Barnum's American museum (Fig. 3). Dawron, who personated both a male and a female, was performing their act by 1860. This is just eight years after Barnum, fresh off promoting Jenny Lind's American tour, purportedly offered to represent Taylor Greenfield's touring aspirations.Footnote 41 Whether Barnum's overtures are historic fact or humbug cannot be ascertained, but the Dawron broadside suggests Barnum swiped the double-voiced concept from Taylor Greenfield's own performances. To begin, Taylor Greenfield was described as “double-voiced” by the New York Press as early as 1853. Dawron's sobriquet was therefore borrowed, as was their act. Like Taylor Greenfield, Dawron sang “duets” with themself across gendered registers. Just as Taylor Greenfield's singing was perceived to cross “black” and “white” sonic idioms, Dawron's performance activated racial masquerade. Unlike Taylor Greenfield, however, whose transgressions were perceived to play out across the invisible realm of the sonic, Dawron played up their act with a tantalizing visual spectacle of gender and racial crossing:

The wonderful and extraordinary double-voiced singer, who produces with equal ease and perfection a Deep and Powerful Tenor and a Sweet and Delicate Soprano, dressed in a singular and unique costume, one half as a Lady, the other half as a Gentleman, a real musical Ella Zoyara, will appear at each performance in a popular Duet, personating both male and female, in dress, voice, gesture, &c., &c. She has been received with great favor, and is regarded as the most musical phenomenon of the age.Footnote 42

Figure 3. Dora Dawron the “double-voiced singer” of Barnum's American Museum, from a broadside on Monday, 17 December 1860. TCS 65 (Box 319: Barnum American Museum 1860–1861), Harvard Theatre Collection, Harvard University.

The Dawron act literalizes Taylor Greenfield's vocal transgressions with costume and physicality that transmute sonic indeterminacy of gender, sex, and race into visual form. Barnum's broadside illustration depicts Dawron as a hermaphroditic schism. Their body has been symmetrically divided from head to toe along sexed and gendered lines, with the axis of difference pivoting through the head, heart, and genitalia. On the left side Dawron is male, with a short coif and lambchop facial hair; their body is dressed in a three-piece morning suit, and their fist rests on their hip, legs splayed, in a posture of masculine authority and status. On the right side, Dawron is female. Their dark hair falls in loose curls to their clavicle, laid bare by an off-the-shoulder neckline. Dawron's bosom is shaded to imply a full bust over a tightly corseted waist. The hip is ample with skirt, the foot stockinged and petite, the hand gloved and hanging demurely and passively just to the side of Dawron's inner thigh, a closed fan symbolically protecting their feminine virtue. Even Dawron's “female” face is partly shielded by the masculine side, as they gaze slightly to their left. Dawron's visual spectacle of male and female “dress,” “gesture,” and voice emphasizes how, in “I'm Free” and other instances of Taylor Greenfield's repertoire, audiences discerned gender masquerade any time Taylor Greenfield sang down the octave, even when the singer herself did not participate in any visual markers of gender crossing.

Dawron's performance also served as a surrogate to contain Taylor Greenfield's transgression of the sonic color line as a Black woman singing white repertoire. Barnum's broadside advertises Dawron as “a real musical Ella Zoyara.” Zoyara was a popular circus rider who performed as female and was “outed” as male by the New York Tribune; Footnote 43 subsequently their riding was advertised with the tag line: “Is she a boy or a girl?”Footnote 44 Importantly, Zoyara was also variously reported to be Creole, and their racial ambiguity was central to their popularity.Footnote 45 Whether or not Dawron was a person of color, the reference to Zoyara within the Dawron broadside functions as a racial dog whistle, hailing audience members as arbitrators in a spectacle of racial passing. These archival doubles reveal how antebellum sex and gender transgressions were always already racialized, and how racialized female subjects were always perceived as gender and sex(ualized) curiosities.Footnote 46

While singing across registers may have functioned as a tactic to showcase the virtuosity of Taylor Greenfield's instrument, this practice also furnished a reliable shock, producing what many reviewers remarked upon as the illusion that both a man and a woman's voice emanated from one body. Suzanne Cusick explains this perceptual surprise; she works from Butler's notion of gender performativity to argue that “male” and “female” registers and timbres are socially constructed and naturalized seemingly to index cis-male and cis-female bodies.Footnote 47 Because of the presumed correspondence among sex, gender, and voice, Taylor Greenfield's transgression of vocal gender norms raised the phantom of another crossing: the boundary understood to cohere between male and female corporeality. Thus, when Taylor Greenfield produced a masculine sound, auditors perceived that she had also materialized and evidenced her body as “male.” As one Boston paper proclaimed, “no male voice could have given utterance to sounds more clearly and strikingly masculine, and people gazed in wonder, as though dubious of the sex of the performer.”Footnote 48

Note the racialization of the above reviewer's assessment: Taylor Greenfield's singing not only confronted gendered expectations for women's voices, but also confronted gendered expectations for Black women. Foreclosed from the sphere of properly “female” (itself reserved for white womanhood), Black women were always already perceived by whites as masculine, a conception attested by auditors who explained the apparent paradoxes of Taylor Greenfield's singing by attributing her performance to that of a male blackface minstrel female impersonator.Footnote 49

If Taylor Greenfield's performance practice unsettled the instrumental arm of intersectional racial and gender oppression, then the Dawron exhibit leveraged the performative technology of sideshow to reproduce racial and gendered power according to the dictates of white supremacy. The Dawron exhibit titillates, for although both their male and female representations appear natural and normative, the very duality of the image signals to audiences a masquerade is underfoot. Of the two competing performances of gender and race indexed by the drawing, half are a dissimulation, or trick. The theatrical technique of “enfreakment” is at play here, wherein bodily human variation is staged as spectacular deviance. Enfreakment produces and consolidates the power of unmarked and able-bodied whiteness while materializing able-bodied whiteness’ constitutive Others.Footnote 50 The theatricality of Dawron's act was predicated on the dramatic tension of an audience's unfulfilled desire to suss out Dawron's authentic sex, gender, and racial identity. Were they a white woman in male drag? A man (of color) in female drag?Footnote 51 Is a spectacle of racial passing underfoot? Or perhaps Dawron was an intersex individual, or gender nonconforming?Footnote 52 Freak exhibits necessarily put these questions to paying audience members who were overwhelmingly white and middle class. Answering those questions enabled white audiences to rehearse their power by marking the differences of Othered individuals.

This rehearsal of power was also an opportunity to enact harm against Taylor Greenfield. Dawron's act enabled audience members, through the proxy of that surrogate performance, to catch Taylor Greenfield in her perceived racial and gender deception—in truth an escape from rigid racialized gender norms for Black women. This type of “gotcha” effect, common to the popular genres of sideshow and minstrelsy, operationalizes what I call sonic slave catching. Footnote 53 Whereas Taylor Greenfield's singing rendered her sex, gender, and race inscrutable, the Dawron double act instrumentalized sonic spectacle to sanction audience members as sonic slave catchers; the ultimate goal of the performance therefore was to apprehend and cordon Taylor Greenfield's body into those deviant categories of race, gender, and sex inaugurated by, and necessary for, the forced reproduction of chattel slavery.

Another double-voiced Taylor Greenfield surrogate, the late nineteenth-century blackface minstrel performer Charles Heywood, brings greater clarity to the imbrication and significance of racial fun and gender masquerade implicit in all of Taylor Greenfield's doubles (Fig. 4).Footnote 54 Heywood was a renowned female impersonator and appeared on the minstrel stage in the stock role of an operatic prima donna. The prima donna character evolved as a stock character in blackface around midcentury, evolving into a whiteface role following the Civil War.Footnote 55 In a prima donna act, a white male minstrel performer engages in a seriocomic female impersonation, singing sentimental vocal repertoire and light opera standards. My own archival research notes the origin of the prima donna as contemporaneous with Taylor Greenfield's appearance on the national stage, and indeed many prima donna acts were in fact surrogate doubles of the Black Swan.Footnote 56 These doubles persisted through the late nineteenth century, and hinged upon a comic bit wherein the Taylor Greenfield surrogate “sings very bad.”Footnote 57 The simple conceit of such sketches was that noise was the blacked-up, sonic parallel to the reductive, visual sign of burnt cork.Footnote 58

Figure 4. Blackface minstrel performer Charles (Chas) Heywood appearing in whiteface as a double-voiced prima donna. Courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center, the University of Texas at Austin.

In this archival photograph, Heywood's minstrel prima donna is linked to Dawron's sideshow spectacle in two ways: both acts animate nearly identical visual tropes of gender duality, and both trade in an implicit Blackness. These visual tropes keyed audience members to recognize sonic tricks of racial and gender masquerade that demanded resolution. Like the broadside image of Dawron, where the racial logic of the print represents the performer as putatively white, Heywood appears in whiteface. This visual whiteness recruited sideshow and minstrelsy audience members to scrutinize singing as a site where racial transgression could be policed and caught. Restated, the visual whiteness of the Dawron and Heywood acts prompted auditors to locate essentialized and stereotypical Blackness in the sphere of the sonic. Yet how was sonic Blackness performatively evoked?

Whiteface performers like Dawron and Heywood relied on visible signs of gender transgression and deviance to impute a reductive Blackness to the sonic spectacle of multiregister singing. Stated otherwise, these surrogate doubles performatively transmogrified Taylor Greenfield's sonically “white” repertoire into Blacksound, the unmistakable sonic thumbprint and “embodied epistemology” of blackface minstrelsy.Footnote 59 They enacted this by mimicking Taylor Greenfield's performance practice and ascribing to it a visual spectacle of sexed and gender freakery and/or carnivalesque inversion. Since sexual and gender deviancy were linked a priori to Black femininity in antebellum America, these visual signifiers of gender and sexed duality elided Taylor Greenfield's cross-register singing with a degraded and fantasied Blackness. Morrison refers to this as “hypersonic” Blackness, a process wherein Black aesthetic innovations are rendered “racially inaudible” as they are appropriated, peddled to, and consumed by white folks, all the while evoking an acousmatic Black body for disciplining.Footnote 60

In the above examples of Taylor Greenfield's surrogate doubles, applying ear training for history reveals how sideshow and blackface minstrelsy staged sound to fabricate the illusion of a natural, one-to-one correspondence between voice and body. These sound acts staged blacked-up sound (sound corresponding to anyone singing multiregister music in or out of blackface) to conjure a gender-deviant, Black female body. Or corporeal spectacles of gender and sexual deviancy (in or out of blackface) materialized Blacksound. In both instances, visual spectacle was deployed theatrically to key intersectional oppression into the sonic register, performatively linking white supremacist regimes for race, gender, and sex across sonic and visual perceptual modalities.

Protecting and preserving white supremacy's investment in the gender, sexual, and racial degradation of Black women, these surrogate doubles restaged Taylor Greenfield's voice and body as a defense against the singer's purported threat to the Union. By training audiences to snatch the singer's escape from categorical and corporeal markers of race, sex, and gender, the sound acts of performers like Dawron and Heywood sought to capture Taylor Greenfield's fugitive transgressions within the white supremacist logic of the slave state. Far from a harmless rehearsal of power, the sonic slave-catching operative in these double acts prepared auditors to enact the legislation that was a very real threat to Taylor Greenfield as she toured the United States from east to west, from Buffalo to Milwaukee, and across cities like Cleveland and Baltimore that rode either side of the Mason–Dixon Line: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Whereas thus far this essay has delineated the visual and sonic dramaturgies through which white supremacy (at)tuned, ear training for history invites auditors to perceive “otherwise” frameworks for historical listening.Footnote 61 Unlike her sideshow and minstrel doubles, Taylor Greenfield did not furnish visual spectacles of racial and gender masquerade as resolution to the double-body problem her audience members thought they heard. Rather, her body countered the visible grammars of sideshow and minstrelsy that auditors desired to project onto her flesh. Taylor Greenfield performed such perfect stillness that even “her face was motionless, unreadable, and uninteresting.”Footnote 62 In what follows, I read this stillness as a sonic key to the “otherwise” schema within which Taylor Greenfield asks contemporary historians to hear.

“I'm Free”: Double-Voiced Strategies for Liberation

Training our ears to history—to how Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's voice acted—requires teasing out the doubled tracks the singer laid down. First, Taylor Greenfield enacted doubleness by performing across the modalities of sight and sound. Specifically, she performed visual stillness in contrast to a voice that seemed to evidence free sonic movement across racial and gender boundaries. Physical stillness and even motionless of expression were hallmarks of Taylor Greenfield's performance practice throughout her career. Indeed, the striking disharmony between the still and immutable body of a Black woman, and a voice that was perceived to conjure bodies male and female, white and Black, is key to Taylor Greenfield's radical aesthetic. Her refusal to offer visible resolution between her still body and doubled voice was a direct challenge to the structures of white supremacy that sought to control how the singer could be heard then and now. To clarify, challenging the structuration of sound by vision was a way for Taylor Greenfield to score listening on her own terms; in what follows I read her sound acts as prompts toward her desired modality for a hearing.

The second thread of doubling in Taylor Greenfield's singing is of course the way her voice evoked auditors’ perceptions of multiple bodies. “I'm Free” dramatized this perception, mapping Taylor Greenfield's multiregister and sonic color-line-defying instrument onto the distinct roles of a white male enslaver and a Black female bondswoman in a scene of fugitive escape. Remarkably, the racial melodrama of this emancipation scenario lends “I'm Free” the same spectacular and sensationalist appeal peddled by each of her minstrel or sideshow doubles. Defined by Linda Williams, racial melodrama is a genre of moral theatre wherein Black characters suffer, and whites (characters and audience members alike) cross the color line in interracial sympathy. Though an apparently progressive genre, Williams highlights the conservative nature of racial melodrama, a genre that uses feeling to dissimulate political action, and thereby reinforces America's status quo by staging Black suffering for white edification.Footnote 63

“I'm Free” was composed by Glover in the vein of the abolitionist Uncle Tom's Cabin, and the work was dedicated to the Duchess of Sutherland, a known abolitionist;Footnote 64 yet such antislavery efforts were not entirely free of the same brand of white supremacy that structured Taylor Greenfield's surrogate acts.Footnote 65 Crucially however, Taylor Greenfield's stillness thwarted the visual spectacle of “I'm Free,” instead enacting the song's dramatic sketch through the invisible acts of her larynx. Her body, motionless throughout the song, testified to the inscrutability of the dramatic action playing out inside her flesh. Hidden inside the dark cavities and confines of the body, the sound acts of “I'm Free” literally kept auditors “in the dark” as to how her voice produced the illusion of sonic movement across categories of race, sex, and gender.Footnote 66 Thinking through Daphne Brooks's writing on Henry “Box” Brown's moving panorama Mirror of Slavery and his images of the Dismal Swamp, I conceptualize Taylor Greenfield's throat—it's inscrutable darkness—as likewise a site of “black aesthetic resistance . . . [and] (representational) excess linked to black fugitive imagination.”Footnote 67 Yet unlike Brooks, I position Taylor Greenfield's sound acts less as tools for claiming narrative agency, and more as fugitive movements that enabled her body to slip from discursive enclosure.

I am thus prompted to listen to “I'm Free” not as a ballad in service of white transatlantic abolitionism, but as a standard of liberation defined by, for, and about Black women. For Taylor Greenfield, the stillness of her Black female body shaded the signification of her sound acts, producing an opaqueness around both the meanings of her corporeality and her song. This double act enabled Taylor Greenfield to rescript Black women's liberation as sonic flight across white supremacist categories of race, gender, and sex, while paradoxically accomplishing this fugitive movement in a body that remained visibly at rest. Such a performance so challenged the fundamental structures of the chattel slavery system—a system that insisted on rigid categories of racial, gender, and sexual abjection, and that furthermore insisted on the perpetual movement and/or labor of the Black body—that Taylor Greenfield's surrogate doubles worked to force her sound acts into the open, where the visible and kinetic spectacle of sideshow and minstrelsy could seemingly apprehend the singer, recapturing the significations of her voice and body in service of the peculiar institution.

Turning to Taylor Greenfield's performed stillness, I emphasize that her motionlessness does not signal the absence of performed action, but rather indexes a calculated act. Singing is an act of physical labor. Yet Taylor Greenfield dissimulated such labor. As a reviewer noted:

Not the least charm of Miss Greenfield is the singular ease with which she performs the most difficult parts of what she sings. There is, in her case, no distortion of countenance, no straining of the voice, no curving of the neck, no gasping, no pumping for breath. . . . Her rich voice . . . rolls out with sweetness, unmarred by any flaws, and seemingly without any more effort than the mere opening of her mouth.Footnote 68

Curving the neck, distorting the countenance, pumping for breath—the physical acts that can accompany classical singing may appear as mere theatrics. However, the vocal apparatus extends to the entire body. Lifting eyebrows, puckering lips, tilting the head, muscularly expanding and contracting the ribcage, and so on are visibly perceptible acts that actively shape sound. These physicalizations frequently accompany novice singers who rely upon externalization in learning vocal technique. For example, raising the eyebrows may assist singers learning to develop autonomous control over lifting the soft palate. As the necessary skill is learned, externalized behavior is replaced with internal action. To sing effectively without such physical externalization signals Taylor Greenfield had such extraordinary vocal technique that she was able to invisibilize the labor of her vocal acts. In this light, her visible stillness is a calculated and performed choice, a vocal act in and of itself.

Drawing inspiration from Harvey Young's examination of stillness as both a tactic of Black oppression and of Black resistance, I contend Taylor Greenfield's motionlessness signifies on both the forced motionless of the Middle Passage and the coerced movement of slavery.Footnote 69 Such stillness lent cover to the fugitive double voicing of “I'm Free,” enabling Taylor Greenfield to double back and over the performative makings of the Middle Passage, unmaking that alchemy Spillers identifies as turning Black bodies into fungible, chattel flesh, and women's bodies into ungendered vessels for the reproduction of white desire.Footnote 70

When I claim that in singing “I'm Free” Taylor Greenfield acted out a drama of emancipation with her voice, I mean much more than the simple observation that she sung a narrative of liberation by personating two characters. Rather, ear training for history draws attention to how Taylor Greenfield's singing entailed an embodied, theatrical enactment of these character roles through the physical space of her voice. Just as actors may alter their gait, posture, and gestural vocabulary to embody a character, Taylor Greenfield physically altered her instrument to take on the roles of enslaver and bondswoman in “I'm Free.” Though these enactments were invisible to the observer, they nonetheless played out the conflict and change of an emancipation scenario within the sphere of Taylor Greenfield's body. Perhaps she lowered her larynx, repositioned her tongue, or adjusted her breathing technique. Though concealed from the naked eye, these adjustments shaped space within the singer's embodiment. Her double-voiced singing was therefore an act of rebellion insofar as it materialized new corporeal spaces for her to inhabit—spaces she was not supposed to inhabit and that were foreclosed to her outside of song.

Antebellum sound was heavily policed.Footnote 71 Women were effectively barred from singing “low” notes for fear of racialization and monstrosity; Black subjects were precluded from singing “white” repertoire for fear of becoming sideshow spectacle or minstrel burlesque. Because singing is an embodied act, these sonic prohibitions were also corporeal foreclosures. While there is no such thing as “white” and “black” or “male” and “female” voice, there are racialized and gendered vocal techniques.Footnote 72 Thus, for example, an antebellum taboo on white repertoire sung by Black artists is in fact an interdiction of embodied choreography of tongue, teeth, and lips, a set of overtone series (or timbres) and a specific rapport with the glottis, and so on, that has over time performatively congealed as an assemblage of racialized and gendered techniques of the body understood as classical singing.

To identify sounds as racialized and gendered is therefore to identify that corresponding repertoires of bodily acts (those that produce a sound) are similarly marked. Restated, meanings for sound are performatively enacted through bodily acts that are racialized and gendered. Sound does not gain meaning through an essentialized body, but through a performing one—as demonstrated through the preceding examples of Taylor Greenfield's surrogates. How a sound can mean is delimited by and through performance. Further, what a sound can be is delimited by possibilities for a body in performance. Ergo, possibilities for sound are tethered to possibilities for what and how a body can perform.

Taylor Greenfield's performance of “I'm Free” baffled and astounded precisely because her sound invisibly signaled that her body was escaping the conditions of (im)possibility assigned to her perceived Black female corporeality. Unless in servitude to or patronized by whites, Black women's bodies were not to occupy white-only spaces; Black women's bodies were not to take up space reserved for men of any race; and Black women's bodies were not to reside even in spaces designated as female, since the category of “woman” was reserved in mid-nineteenth century for white women only. Yet Taylor Greenfield inhabited each of these spaces through sound. Singing both enslaver and bondswoman offered Taylor Greenfield unprecedented reign over the limits of her body-as-instrument and furnished access to previously foreclosed configurations of her flesh.

Perhaps most crucially, this new mode of bodily autonomy defied the sexual economy of chattel slavery that relied on rape to reproduce both the power structures and material conditions of the slave state. This sexual economy is referenced in “I'm Free” through the lyrics of the enslaver who lusts after the fleeing bondswoman: “That breast, that coal-black hair. . . .”Footnote 73 In personating the roles of enslaver and fugitive, Taylor Greenfield's voice—a bodily agent hidden from plain sight—became quite literally a path of escape and a loophole of retreat, carving out new corporeal spaces for Black female liberation through sounds that act.

Considering that the very categories of race and gender were made in the Middle Passage, I now reconsider Taylor Greenfield's double-voicing in “I'm Free” not as racial and gender crossings (which is indeed how her surrogate doubles and even Glover wanted a future listener to hear), but as a Black feminist aesthetic for uncrossing, or doubling back on, the makings of race and gender in chattel slavery. Insofar as Taylor Greenfield's singing unwed essentialized correspondences between voice and body and scrambled antebellum understandings of race and gender, her double-voicings produced “otherwise” forms of liberation.Footnote 74 Her singing was a critique of the slave state's reliance on the violent enforcement of race and gender as a source of power and coherence. “I'm Free” insisted that Taylor Greenfield's voice was evidence not of doubled bodies, but of a single body containing multitudes. This multiplicity opened previously foreclosed spaces within Taylor Greenfield's corporeality that the singer could inhabit, and barred those spaces to the racialized, gendered, and sexual intrusions of white supremacy. Thus, instead of claiming that Taylor Greenfield sang male and female, Black and white—cognitive schemata that serve the project of white supremacy—ear training for history posits that the historian cannot know what these newly corporeal spaces and sounds signified for Taylor Greenfield. Rather, ear training for history identifies how racial and gender binaries were not, and no longer serve as, useful avenues for listening to “I'm Free.” In lieu of the epistemic certainty of white supremacy, ear training for history offers a modality of listening that identifies Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's singing as a performative enactment of the capacious possibilities for her being and flesh.

In contrast to political models of emancipation that hinged on a discourse of “from slavery to freedom,” in “I'm Free” Taylor Greenfield demonstrates freedom on its own terms, achieved by, for, and about Black women's embodiment. If, drawing from Crawley's conceptualization, Taylor Greenfield's flesh was “vibrational and always on the move,”Footnote 75 her kinetic but invisible sound acts enacted a liberation wherein her voice doubled back across the racial and gender regime of the slave state, but her visible body claimed stillness, peace, and rest. Thus, Taylor Greenfield's sung declaration “I'm Free” was a performative sound act—an enfleshed instantiation of liberty that exceeded her precarious legal status under the Fugitive Slave Act, her imbrication with white abolitionist networks of support, and even the proclamation yet to come. Rather, the freedom Taylor Greenfield sang forth was a liberty in and of herself, a liberty of radical self-possession that paved the way for generations of Black femme vocalists to follow.

Conclusion: Listening and Liberation in the Archive

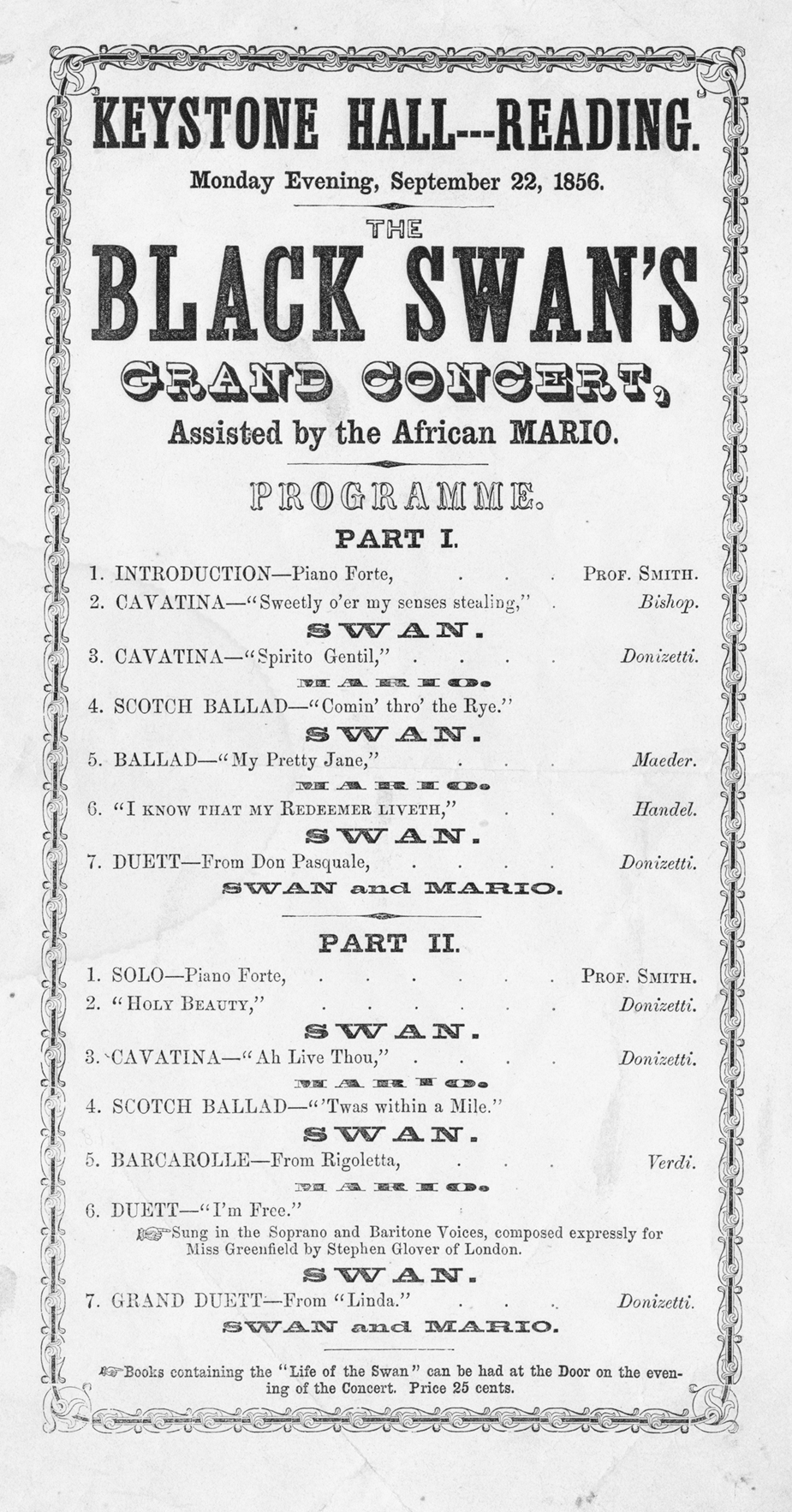

I have attributed a great deal of power to Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's “I'm Free.” Whereas the unique dramatic emancipation scenario of the song first drew me to think about Taylor Greenfield's performance of the piece, it was the work's programming in 1856, three years after her return from abroad, that primed my ear to listen for a different way of interpreting her performance (Fig. 5). The 1856 program evinces Taylor Greenfield's role within Philadelphia's vibrant African American community: the program bills the singer as “assisted by the African Mario,” her pupil, one Thomas J. Bowers.Footnote 76

Figure 5. An 1856 concert by Taylor Greenfield and her pupil, Thomas Bowers. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

How might a scholar hear “I'm Free” on this program with an ear that attunes to an accomplished singer cultivating Black vocal talent, one who would go on to perform alongside Frederick Douglass in support of the Thirteenth Amendment, and sing in support of Mary Ann Shadd's appearance at the Colored National Convention in Philadelphia? What was the relationship between Taylor Greenfield's unique double-voiced singing and her activism—so routinely overlooked in scholarship on Taylor Greenfield but so evident in this broadside? Why would Taylor Greenfield put “I'm Free” on this program of Black talent? Why would she continue to duet herself when she had a male artist with whom she could enact Glover's dramatic sketch? Why did she program “I'm Free” in the penultimate and most climactic place on the evening's bill? How might a better “ear for history” shed light on the trailblazing nature of Taylor Greenfield's aesthetics and activism at a time when Black women were intentionally cut out of both spheres: the properly aesthetic and the properly political?

Taylor Greenfield's reception by the Black press was overwhelmingly positive and reflected the philosophy of racial uplift: a Black woman singing respectable music in public was activism enough in and of itself. This discourse has deeply impacted scholarship on Taylor Greenfield, which has largely overlooked the political and aesthetic interventions of her singing. I have endeavored to demonstrate that, at a time when most auditors could not hear Taylor Greenfield beyond the racial and gendered biases of their own listening, “I'm Free,” with its overt dramatization of Taylor Greenfield's double-voiced performance practice, ironically staged the one perception of the singer's voice that auditors heard correctly: its escape beyond, and therefore its threat to the conceptual and corporeal fundament of the American slave state.

Ultimately, the explicitly dramatic scenario of fugitive escape in “I'm Free” provided the evidentiary clues to assist me in developing an ear for history, a mode for recognizing Taylor Greenfield's voice as an embodied site where theatrical performance inaugurated sung moments of Black feminist liberatory and aesthetic action. However, Taylor Greenfield's voice was always already perceived as theatrical, even when she was not explicitly conjuring personas Black and white, female and male, enslaved and enslaving. Auditors heard the singer's duets with herself as dramatic conflicts between diametrically opposed bodies and identities, and as demonstrated by Taylor Greenfield's surrogate double acts, sought to resolve such perceived conflict through popular acts of sonic slave catching that would symbolically recapture the Black Swan in the racial and gendered logic of the slave state.

Attending to the perceived theatricality of Taylor Greenfield's double-voiced singing through the filter of “I'm Free” enables me to train my ear to how the singer used her voice to double back on white supremacist categories of race and gender, and redefine freedom each and every time she initiated her signature double-voiced performance practice. Thus, although “I'm Free” is the test case of this essay, I contend that Taylor Greenfield redefined liberation by, for, and within her own corporeality even when Glover's composition wasn't on the program. Stated otherwise, there is nothing inherently liberatory about “I'm Free” outside of Taylor Greenfield's performance practice, a praxis that dates to her earliest public performances. The ballad “I'm Free” and its 1856 programming are merely archival ephemera whose explicit theatricality pricked my ears to new possibilities for hearing Taylor Greenfield's song.Footnote 77

And finally, I emphasize that whereas ear training for history began by historically tracing the theatrical enactments of Taylor Greenfield's voice in “I'm Free,” the method concludes by demonstrating how, in doubling back over and doubly crossing the racial and gendered logic of the slave state, we must also question the analytic of theatricality as a productive avenue for listening to and hearing her voice. Although this essay has recuperated theatricality as a research method for listening to sonic Black feminist activism, hearing Taylor Greenfield from such a vantage risks reifying the strains of misogynist anti-Blackness of those who insisted on hearing her voice as double, and not simply as. Far from exercising an antitheatrical impulse, ear training for history asks historians to root out rigorously the strains of misogyny and anti-Blackness that cling to our most well-established disciplinary tools. At the very least, ear training for history hopes that provoking interdisciplinary inquiry provides disparate disciplines (in this case theatre and musicology) with new opportunities for antiracist research and collaboration. Ultimately then, this study of “I'm Free” draws listeners’ attention to two new liberatory modalities: the politics and aesthetics of Black feminist abolitionism, and a sonic, practice-based archival methodology. If in “I'm Free” Taylor Greenfield found herself “free as air,” this essay hopes to draw its readers' ears to the vibrating messages of that—and to other sounds that act.

Caitlin Marshall, Senior Lecturer at the School of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies, University of Maryland College Park, received her Ph.D. in Performance Studies from the University of California, Berkeley. Her manuscript in progress, “Power in the Tongue: Sounding America in Red, Black, and Brown,” is a cultural history of what it meant to sound American in the nation's first independent century. She has held fellowships at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at UPenn, and the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, and is a recipient of the 2021 ASTR fellowship for scholarly research. Her writing is published in Theatre Survey, the Journal of the American Musicological Society, Performance Matters, Postmodern Culture, Twentieth-Century Music, and Sounding Out!.