We team teach an interdisciplinary political science and literature course titled “Violence and Reconciliation,” which features case studies on the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and on debates about whether to develop a TRC in Northern Ireland after The Troubles. During the semester, students read and discuss works by scholar and peace activist John Paul Lederach, a range of treatises by social scientists and human rights advocates, documentary work, fiction, and dramatic films. The course culminates in a two-week simulation in which students role play the experiences, strategies, and needs of victims, perpetrators, legal teams, government officials, and NGOs in the aftermath of a horrific event that has torn a society apart.

What led us into team teaching this course was our mutual interest in reconciliation, restorative justice, and problem-based learning. One author is a literary scholar who studies fiction produced in response to apartheid as part of the larger effort to create new communal bonds founded on witnessing, forgiveness, and commitments to social justice. The other author is a political theorist interested in employing features of restorative justice and radical democracy to advance a just transition away from a carbon-based economy to a steady-state economy fueled by renewable energy sources in the face of global climate change. These distinctive research interests combine to offer our students a sense of the need to work in interdisciplinary teams in response to complex political and moral problems. We also consciously work to provide students with an example of the intellectual excitement and pedagogic benefits of cooperative teaching, and we drew on both disciplinary backgrounds to develop the simulation. We have since taught three iterations of the course. We feel confident that the simulation is an effective way to help students move from a scholarly engagement with the tools and processes of restorative justice to employing them in response to trust-effacing hatred and violence.

We feel confident that the simulation is an effective way to help students move from a scholarly engagement with the tools and processes of restorative justice to employing them in response to trust-effacing hatred and violence.

This article describes the simulation for use or adaptation in other courses.

CRITICAL CONCEPTS

At the center of the course is an exploration of restorative justice, which is best grasped in contrast with retributive justice. Whereas the latter seeks to punish the perpetrator of a crime after a legal process that ends in a verdict, the former seeks to repair the harm done by the crime and heal the underlying membrane of trust that supports the social order. Restorative justice illuminates the limits of legal retribution and the need for a new political vision to move forward. This response is composed of two parts. The first is revealing the truth of what happened through testimony. The second is reconciliation achieved through a process that brings perpetrators and victims into face-to-face encounters, which can empower victims and rehumanize their relationship with those who have harmed them.

Restorative justice is best known for its role in large-scale political transitions, especially TRCs. In a TRC, perpetrators and victims of violence testify to their experiences and a society that previously denied atrocities condemns those acts and bears witness together. Punishment is not the goal; renewal of political space and community is. In the South African TRC, which formed a model for TRCs around the world, perpetrators who gave a full accounting of their crimes and proved that they had political motive received amnesty (i.e., exemption from prosecution). Restorative justice also can take place at a smaller scale. It emerged as an alternative to criminal justice prosecutions in the 1970s. Many college campuses have restorative justice processes in which offenders, those they have harmed, and members of the broader community share their perspectives. Together, participants develop a plan for the offenders to redress the harm they caused and to be reintegrated into the community.

Restorative justice is taught across a variety of disciplines, from political science to philosophy, sociology, and criminal justice (Armour Reference Armour2013). There is widespread desire for ways of teaching restorative justice that use its principles and practices, such as listening to diverse voices, bridging theory and practical application, and creating opportunities for collaborative decision making (Armour Reference Armour2013; Smith-Cunnien and Parilla Reference Smith-Cunnien and Parilla2001; Zehr Reference Zehr2002). Our simulation accomplishes exactly this, making all voices central to the decision-making process as we ask students to “translate theoretical knowledge into a meaningful response to the demands of uncertain situations” (Armour Reference Armour2013, 118).

Two key concepts in our course are moral imagination and multiple types of truth, which help students grasp the value and risks of a turn to restorative justice. “Moral imagination,” delineated by Lederach (Reference Lederach2005), consists of four principles necessary for peace building in a context of violence with a long history and a corresponding appearance of insuperability. The first principle of the moral imagination is the “centrality of relationships” in which we recognize ourselves as part of a pattern of the violence we want to end. The second principle is “paradoxical curiosity,” which entails an elimination of dualisms—us versus them; we are good, they are bad—through the pursuit of something better than what the present offers. This pursuit entails reimaging the structures, beliefs, and institutions that perpetuate divisions and injustices. The third principle is the provision of space for creative work: a willingness to do the unexpected in order to create social relationships that transcend seemingly intransigent divisions. The fourth principle is a willingness to take risks: an openness to the vulnerability of reaching out to someone who has harmed us, or someone we have harmed, without any assurances of success. We frame our restorative justice teaching with the moral imagination to provide students with ways to reimagine social relationships as a key to moving from violence to reconciliation.

We also consider various forms of truth, drawing on the South African TRC's distinction among four types of truth: objective/forensic (establishing what happened); personal/narrative (expressing individual, affective responses); social/dialogue (creating space for conflicting perspectives); and healing/restorative (helping to bring a community together). Because restorative justice is premised on every participant sharing their account, we want students to see how testimonies can work at all of these levels. Students also must confront tensions between forensic and narrative truth. Personal (narrative) truth may be distorted by and mirrored in trauma. This form of truth is accurate in an emotional register, but it challenges representational notions of truth. In the simulation, students must confront testimonies that are expressions of horrible pain and shame as a result of torture and street violence. Should these testimonies be dismissed because a victim misremembers a location or the sequence of what happened? How can restorative justice practices best respect the psychological weight of narrative truth while striving to document the facts? Our simulation helps students to grasp the nuances of moral imagination and the interplay among different types of truth. What students may have rehearsed imaginatively in their consideration of characters in works of fiction or subjects of documentaries, biographies, and autobiographies takes on an immediacy and urgency in the simulation.

Our simulation helps students to grasp the nuances of moral imagination and the interplay among different types of truth. What students may have rehearsed imaginatively in their consideration of characters in works of fiction or subjects of documentaries, biographies, and autobiographies takes on an immediacy and urgency in the simulation.

Students hear classmates advance divergent narrative truths and strive to respond to conflicting accounts with respect and sensitivity. They apply moral imagination as they reconsider the webs of relationships that connect them to one another within the world of the simulation, challenge us-versus-them views, think creatively about ways to redress histories of violence, and risk putting themselves in unfamiliar positions by identifying with experiences different from their own. The work that students do in the simulation complements their essays and exams by giving the critical concepts new weight and by helping them to probe the value and challenges of restorative justice. It also enhances our ability to assess their learning because of the increased range of opportunities to display their understanding of critical concepts.

THE SIMULATION

The simulation blends fiction and political science through a futuristic setting featuring major social upheaval caused by a global health crisis. (For the full simulation narrative, see online appendix A.) We wrote the simulation several years before COVID-19, but it takes on new relevance now in the face of a pandemic that has put existing divisions into relief as people of color, Indigenous communities, and low-income communities are disproportionately affected and as political ideologies shape policy responses. Our simulation is set in the United States in 2072, after a three-decade pandemic caused by a fictional antimicrobial resistant bacterium called pseudomonas genesis (P-Gen). In our narrative, the US government responded to the crisis by diverting resources to genomics, epidemiology, and drug development and delivery systems. Scientists, engineers, and physicians became a privileged class, living and working in gated compounds and provided with state-of-the-art equipment, plentiful food, and comfortable housing. Outside of the compounds, the nation's infrastructure fell apart and resentment against the “scientific class” flourished.

In the late 2060s, a newly formed political party called the Health and Freedom Party capitalized on this resentment to undermine the two-party system that had dominated US history. The Health and Freedom Party took power in democratic elections in 2068. It held the “scientific class” responsible for failure to stop the pandemic, labeled scientists “parasites” unworthy of government protection, and incited violence against scientists and their families. Mobs attacked the compounds, sometimes using military-grade weapons, as police looked the other way. Against this backdrop, the Health and Freedom government began interning scientists and physicians, ostensibly for their own safety. Internment camps were run by military guards; conditions were terrible and thousands died of disease, exposure, and starvation.

By the simulation's “present day,” more than 10 thousand people had been killed by mob violence and thousands more had been imprisoned in internment camps. Finally, news broke that researchers in Beijing had created an antibiotic showing signs of success. Amid reports of vaccine development and falling death tolls, mob violence diminished. A grassroots peace movement formed the New Beginnings Party and won a national election in 2072, hoping to unite the country and start rebuilding shattered trust.

We drew inspiration from a range of sources, including South Africa's transition to democracy, Japanese internment camps in the United States, and growing concerns about antimicrobial resistance. Plot inspiration also came from Atwood's (Reference Atwood2003) dystopian novel Oryx and Crake, in which scientists live in gated compounds as environmental disasters and economic inequality devastate the United States until a genetic engineer develops a pandemic that destroys the population. We made scientists, engineers, and physicians the primary targets of persecution because Clarkson University, where we teach, is a predominantly engineering-based institution. Most students in our course are engineering and science majors fulfilling general education requirements.

Our students entered the storyline in December 2072, with the federal government in transition. We explained that the United States was starting to move past the health crisis but the country was fractured by hate and mistrust. The president-elect was calling for people on all sides of the conflict to collaborate in establishing a transitional justice mechanism. The incoming administration insisted that the Health and Freedom government, the military, victims' advocacy organizations, and members of the scientific community must all be involved for the political transition to yield long-term stability. Faced with public pressure, all of these groups agreed to participate in negotiations, but some were more sincere than others.

Everyone in the class became a member of the President-Elect's Commission for Transitional Justice. We define “transitional justice” in terms of institutional changes needed to prevent any return to the earlier, violent order while planning and perpetuating a more just and stable society. We assigned each student a specific role. (For the full cast list, see online appendix B.) These roles included two government contingents, consisting of a sitting and an incoming president, vice president, and secretary of defense; and a military contingent, including, among others, a general whose brigade ran internment camps and a lieutenant stationed at one. The rest of the class were victims' advocacy organizations, members of persecuted groups (i.e., scientists, physicians, and engineers), and legal counsel for state actors accused of violence.

Students were told that a successful resolution meant agreement on a transitional justice plan for the country. It could combine restorative and retributive justice, and it could encompass national initiatives such as a TRC along with grassroots initiatives such as community storytelling circles. The plan had to be detailed. For example, if students selected a TRC, who would run it? Would there be an amnesty provision? What would be the conditions for amnesty? Could people be compelled to testify? What would happen to people denied amnesty?

A successful agreement required the following two criteria:

-

• support from the majority of the class

-

• majority support from the two groups with the power to derail a peaceful transition (i.e., the outgoing government and the military)

The second criterion was based on the negotiations that led to the South African TRC, in which an amnesty provision was necessary to persuade the National Party government and the military to support democratic elections. We wanted to show students that political transitions must contend with realpolitik and force them to negotiate with groups they otherwise might have excluded. We recognized that even after a semester of theorizing about truth, reconciliation, and restorative justice, students might gravitate to punitive forms of justice and ignore the voices of perceived perpetrators.

We started by asking students to write a combined biography and position paper, inventing backstories for themselves and developing preliminary positions about the transitional justice mechanisms they wanted to see. Then they caucused with their groups (e.g., victims' advocates, military, and incoming/outgoing governments) to produce preliminary recommendations. We emphasized that although these groups were natural allies on the surface, they did not have to agree, and students could seek other allies if they chose. During the following two weeks, class periods combined informal breakout negotiations and full-commission sessions. To maximize student agency, we assigned those students representing the incoming government to moderate commission meetings. We punctuated the two weeks with “breaking news” reports framed as newspaper articles and delivered through Moodle, Clarkson's online content-management system. (For our breaking news articles, see online appendix C.) We wrote the reports based on student discussions in order to complicate their thinking and dramatize the pressures involved in restorative justice. At the end of the course, students were graded holistically, as in a class-participation grade, based on their contributions to class negotiations, written biographies and position papers, and online negotiations in Moodle. The simulation counted for 10% of their final course grade.

ASSESSING THE SIMULATION

To assess the effectiveness of the simulation, we asked students to write pre-simulation and post-simulation reflections—both of which were 20-minute, ungraded, in-class exercises—and we followed these reflections with a closely related question in the final exam.

-

• Pre-simulation reflection: In your view, to what extent can mass trauma be surmounted on a social level? What are the potential benefits and drawbacks of criminal trials, truth commissions, and other storytelling mechanisms for moving past mass trauma? What conditions would lead you to support one or the other?

-

• Post-simulation reflection: How has the simulation changed your views about the potential and challenges of surmounting mass trauma on a social level? Based on the simulation, what are the potential benefits and drawbacks of criminal trials, truth commissions, and other storytelling mechanisms for moving past mass trauma? What considerations led you to support one or the other?

-

• Closing question, final exam: What insights did the P-Gen simulation give you about the benefits and drawbacks of truth and reconciliation commissions compared to criminal trials after widespread violence? Under what conditions would you recommend restorative justice mechanisms, either on their own or in combination with traditional judicial responses?

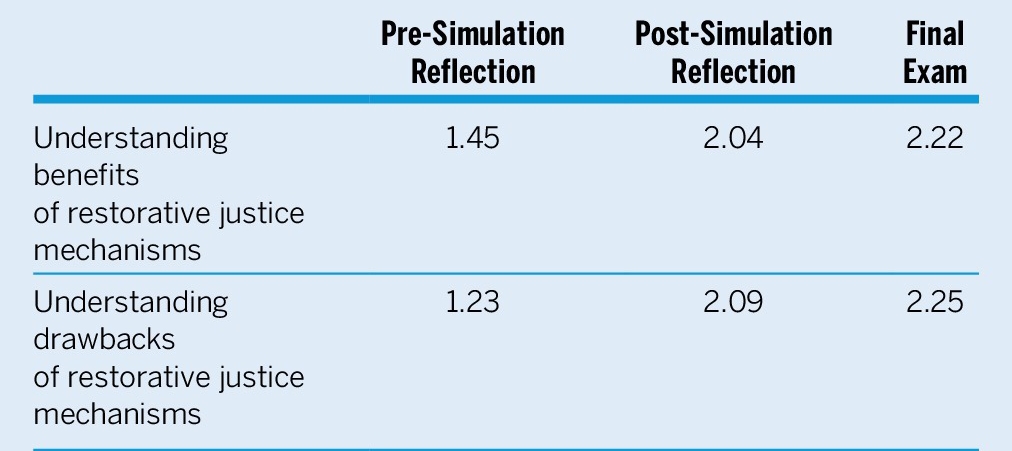

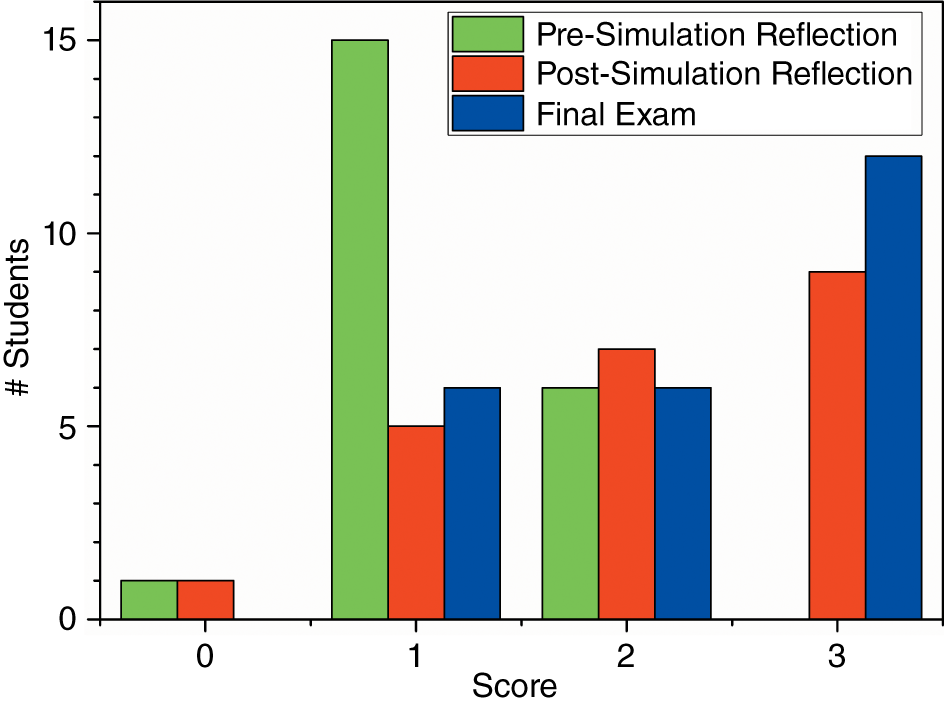

Using a four-point rubric (table 1), we assessed each response for its understanding of (1) the benefits, and (2) the drawbacks of national restorative justice initiatives. The results are shown in table 2 and figures 1 and 2 and are available on Harvard Dataverse (Propst and Robinson Reference Propst and Robinson2020).

Table 1 Assessment Rubric

Table 2 Students' Average Scores

Figure 1 Number of Students with Each Score (Understanding Benefits of Restorative Justice Mechanisms)

Figure 2 Number of Students with Each Score (Understanding Drawbacks of Restorative Justice Mechanisms)

Written reflections showed clear improvement in understanding the benefits and drawbacks of national restorative justice initiatives. The pre-simulation reflection took place two thirds of the way through the semester, when students had written two papers about transitional justice based on the case studies. At that point, they demonstrated, on average, broad understanding of these issues. By the end of the semester, average understanding had increased by nearly one full point, from a broad understanding to a thoughtful account of the benefits and drawbacks of national restorative justice initiatives. Whereas hardly any student scored a 3 in the first reflection, by the end of the semester, nearly half of the class demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of one or both issues.

Illustrative Examples

Two weeks of intensive negotiations made students viscerally aware of the challenges of restorative justice. Several noted that tailoring restorative justice mechanisms to the needs of the nation takes time, whereas in periods of upheaval, there often is pressure to move forward quickly. A few observed that it was difficult to move past ingrained associations between justice and retribution. One student wrote: “I found…we as a group were actively seeking ways in which we could incriminate the ‘guilty’ members” while developing a TRC. This shows the seductiveness of retributive justice and the difficulty of moving away from familiar judicial models to create a new political vision.

Students also revealed important insights into the value of restorative justice. By the end of the simulation, many students were committed to dialogue as a cornerstone of national healing—even if testimony was not always healing or cathartic on an individual level. One student declared: “I feel like restorative justice is necessary for a nation to work together and to achieve a sense of unity and trust.” Ultimately, most students believed the primary benefit of restorative justice was its potential to connect people across political and experiential divides. As one student mused in the final exam, restorative justice “forces people to live and work together, rather than separate society and allow divisions to foster.” These responses demonstrated that students internalized Lederach's (Reference Lederach2005) concept of moral imagination. They elevated relationships above more abstract forms of justice and illustrated paradoxical curiosity by striving to push past us-versus-them mentalities. Students also recognized that people might hold different truths depending on the roles they had played in the conflict; uniting people across political divisions required openness to these divergent truths.

Paradoxical curiosity and sensitivity to the importance of social relationships were particularly visible in student debates about amnesty and deconstructions of the perpetrator–victim binary. Initially, many students opposed amnesty for perpetrators of human rights violations. Ultimately, they agreed on an amnesty provision similar to that in the South African TRC, in which perpetrators were amnestied if they proved political motive and gave a full disclosure of their acts. Our students' views changed as they realized that, as community members, they were interdependent. They needed to work together and meet one another's needs if they wanted to reach an agreement and create societal progress.

Our students' views changed as they realized that, as community members, they were interdependent. They needed to work together and meet one another's needs if they wanted to reach an agreement and create societal progress.

Moreover, students became less focused on retributive justice as they understood that people can be both perpetrators and victims, or “perpetrator–victims,” as one student put it in a phrase that caught on with the class: a person who experienced trauma or oppression also might carry out violence. Students understood that the multiple truths of a person's experiences often defied fixed labels such as perpetrator/victim and aggressor/aggressed. They recognized people who had perpetrated violence as part of a web of communal relationships rather than simply labeling them as villains. They showed paradoxical curiosity by challenging binary structures of thought and acknowledging multiple perspectives. By practicing moral imagination, they prioritized “the reunification of divided people” and the importance of allowing “victims and perpetrators, and everyone else, to begin to heal” (in the words of one student's final exam).

Along with a growing understanding of the nuances of restorative justice, students showed increasing competence in translating theoretical information into practical action (a key component of restorative justice). Students were not simply trying to replicate the South African TRC but rather were striving to build a transitional justice mechanism shaped by the political and social context into which they had been thrust. In Lederach's (Reference Lederach2005, 38–39) terms, this meant they needed “space for the creative act” and “willingness to risk”—to suggest ideas outside of the frameworks they had studied, even if those ideas ultimately might not work. Students argued about how much information amnesty applicants should be required to disclose and whether psychological motives (e.g., trauma) could count as grounds for amnesty. They recognized that national truth-telling initiatives are only one step in peace building, and they offered creative proposals for social reform and victim support including symbolic financial reparations, restored funding for science and engineering, new judicial structures, and an independent national ethics committee. In keeping with the ethos of restorative justice, their proposals emerged through dialogue in which people who had been impacted in different ways by the conflict articulated what they needed to move forward. The creativity of these responses showed that students were not simply recalling and repeating course information but instead applying their knowledge to a new and constantly changing context. In Lederach's (Reference Lederach2005, 38) terms, students moved “beyond what exists [in the present] toward something new and unexpected while rising from and speaking to the everyday.” The challenges that students faced in developing proposals that addressed the needs of the entire community, as well as the creativity involved, show that no abstract notion of justice alone can restore communal relations in the face of long-term violence. If restorative justice is predicated on respectful and equitable communal relations, it must be developed from within as a first-order practice, shaped by the perspectives and needs of the individuals involved.

Limits of the Simulation

A few students showed no improvement in the written assessments, although some revealed important insights during the negotiation process; they simply struggled to consolidate those insights on paper. This suggests that students might benefit from more frequent individual writing assignments during the simulation, which could help them to express their ideas and provide an additional communication channel for those who are uncomfortable speaking up in large-group settings.

Another potential change concerns the focus of the negotiations. Each time we have taught the course, most of the negotiation time has focused on justice systems: that is, on the question of whether and how to develop a TRC. Yet, some of the most creative thinking emerged when students moved away from the mechanics of a TRC and offered alternative proposals for social reform and victim support (such as in the previous examples), as well as smaller-scale reconciliation processes such as grassroots dialogue circles. In the future, we will revise our instructions and “breaking news” articles to encourage more discussion about social reform and community-level reconciliation mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

Justice as retribution—a legal process that results in punishment for those found guilty—often monopolizes our students' thinking about societal responses to crime and upheaval. It is a difficult intellectual and political habit to challenge or break. Building a course like “Violence and Reconciliation” around a simulation gives students an opportunity to work with concepts and processes that present alternatives to retributive justice. As our experience has shown, students take seriously the enterprise of designing a new justice system that functions to prevent further violence by strengthening the bonds of community. Moreover, they enjoy the difficult work of role playing and negotiation. This engagement with the course material fosters acts of creativity when it complements a TRC with ongoing mechanisms of care for victims and reparations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all of the students in our “Violence and Reconciliation” course, especially the 2018 class whose work is analyzed in this article. We also thank our colleague Christina Xydias for her generous advice about assessment.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials are available on Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZHYKSD.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520001626.▪